Abstract

Spectrum sensing is a key technology enabling the cognitive radio system. In this paper, the problem of how to quickly and accurately find an unoccupied channel from a large amount of potential channels is considered. The cognitive radio system under consideration is equipped with a narrow band sensor, hence it can only sense those potential channels in a sequential manner. In this scenario, we propose a novel two-stage mixed-observation sensing strategy. In the first stage, which is named as scanning stage, the sensor observes a linear combination of the signals from a pair of channels. The purpose of the scanning stage is to quickly identify a pair of channels such that at least one of them is highly likely to be unoccupied. In the second stage, which is called refinement stage, the sensor only observers the signal from one of those two channels identified from the first stage, and selects one of them as the unoccupied channel. The problem under this setup is an ordered two concatenated Markov stopping time problem. The optimal solution is solved using the tools from the multiple stopping time theory. It turns out that the optimal solution has a rather complex structure, hence a low complexity algorithm is proposed to facilitate the implementation. In the proposed low complexity algorithm, the cumulative sum test is adopted in the scanning stage and the sequential probability ratio test is adopted in the refinement stage. The performance of this low complexity algorithm is analyzed when the presence of unoccupied channels is rare. Numerical simulation results show that the proposed sensing strategy can significantly reduce the sensing time when the majority of potential channels are occupied.

Index Terms: CUSUM, multiple stopping times, quickest spectrum sensing, sequential analysis, SPRT

I. Introduction

One of the crucial tasks in the cognitive radio system is to constantly monitor the potential spectrum bands and detect the activities of primary users in order to access the unoccupied channels. In this research, we consider a sequential scenario in which the secondary user has a large number of potential wireless channels, but the secondary user is equipped with a narrow-band sensor so that it can sense these channels only in a sequential manner. Spectrum sensing has to meet several demanding requirements to guarantee the reliability and the high-performance of system. On the one hand, a small sensing error is required to avoid the potential interference to the primary network caused by the secondary user when he accesses the licensed band. On the other hand, a small detection delay is also essential for the spectrum sensing. To this end, several sequential probability ratio test (SPRT) based sensing algorithms have been proposed. For example, [1] adopts truncated SPRT and [2] proposes a sequential shifted chi-square test for spectrum sensing. [3] proposes a concatenated SPRT algorithm and shows that the proposed algorithm is optimal when the sensor aims to identify the status of all candidate channels. The motivation of such sequential algorithms is that SPRT achieves the minimum average sample size (or detection delay) for both the null and the alternative hypothesis under any given false alarm probability and mis-detection probability constraint in simple binary hypothesis problem [4]. Hence, a proper modification of SPRT is expected to outperform over fixed sample size test algorithms.

The quickest search over multiple sequences problem, originally proposed in recent paper [5], can be potentially applied into the area of multi-band spectrum sensing. In particular, if we assume the observations from an occupied frequency bands have distribution f1 and those from unoccupied bands have distribution f0, [5] considers the case that a sensor sequentially takes observations from those spectrum bands and aims to find a channel with distribution f0 as quickly and reliably as possible. If the sensor can only take one observation from a single channel at a time and no switch-back is allowed, [5] shows that the cumulative sum (CUSUM) test [6], [7] is the optimal search strategy.

In this paper, we extend the setup in [5] and propose a new sequential sensing algorithm for multi-band spectrum sensing, which is called mixed observation sensing strategy. The proposed sensing strategy consists of two stages: the scanning stage and the refinement stage. In the scanning stage, the cognitive radio system takes observations that are linear combinations of signals from two different frequency bands. The purpose of this stage is to quickly identify a pair of channels among which at least one of them is highly likely to be unoccupied. In particular, if the sensor believes that both channels that provide samples are occupied, then it discards this pair of channels and switches to observe another two new channels. Otherwise, the system stops the scanning stage and enters the refinement stage. In the refinement stage, the observations are taken from one of the two candidate channels identified in the scanning stage. The system makes a final decision on which one of these two channels is unoccupied. Hence, in the refinement stage, no mixing is used anymore.

The motivation to propose this mixed observation sensing strategy is to improve the sensing efficiency when the presence of f0 is rare. If most of the channels are generated by f1, then the sensor can scan through and discard the channels more quickly by this mixed strategy. Our strategy has a similar flavor with that of the group testing [8] and compressive sensing [9], [10] in which linear combinations of signals are observed. In a practical view, the proposed sensing strategy can be easily implemented. Since signals from different channels have different carrier frequencies, the mixed sensing strategy can be implemented as follows: in the scanning stage, the received signal is demodulated by the sum of two sinusoidal signals, each with frequency tuned to the carrier of a channel of interest. By passing the demodulated signal through a low pass filter, the receiver obtains sum of two baseband signals. In the refinement stage, the receiver can demodulate the received signal by a single carrier wave, hence the based band signal from the corresponding channel is obtained. Therefore, the proposed mixed observation strategy can be easily implemented by adjusting the demodulated frequency in the receiver.

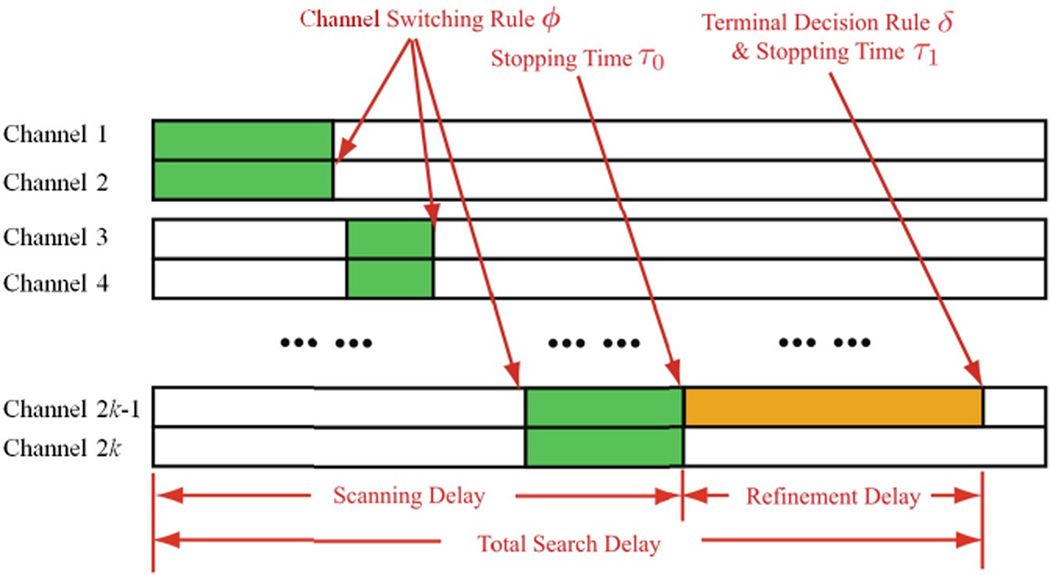

With this mixed observation strategy, our goal is to minimize the average sensing delay under a false identification error constraint. By Lagrange multiplier, this problem is equivalent to minimize a linear combination of the sensing delay and the probability of false identification. Toward this goal, we optimize over four decision rules: 1) the stopping time for the scanning stage τ0, which determines when the sensor should stop the scanning stage and enter the the refinement stage; 2) the channel switching rule in the scanning stage ϕ, which determines when the sensor should switch to new channels for scanning; 3) the stopping time for the refinement stage τ1, which determines when the sensor should stop the whole sensing process; and 4) the final decision rule in the refinement stage δ, which determines which channel will be selected to be unoccupied. Figure 1 illustrates this sensing strategy. This two-stage sensing problem can be formulated as an optimal multiple stopping time problem, which is studied very recently in [11]–[13]. In particular, we show that this problem can be converted into an ordered two concatenated Markov stopping time problems. Using the optimal multiple stopping time theory [12], we derive the optimal strategy for this sensing problem. We show that the optimal solutions of τ0 and ϕ are region rules. The optimal solution for τ1 is the time when the cost of the false identification is less than the future cost, and the optimal decision rule δ is to pick the channel with a larger posterior probability of being generated by f0.

Fig. 1.

Two stage sensing strategy

Unfortunately, the optimal solution for this mixed observation sensing strategy has a very complex structure. For implementation purpose, we further propose a low complexity sensing algorithm in which the sensor adopts CUSUM in the scanning stage and adopts SPRT in the refinement stage. The asymptotic performance of this low complexity algorithm indicates that the average sensing delay of the mixed sensing strategy is dominated by the sensing delay in the scanning stage. We analytically derive the expression of the sensing delay of the proposed low complexity mixed observation sensing strategy, which also serves as an upper bound of the performance of the optimal strategy. Numerical simulation results show that the proposed strategy could save 40% of sensing time than the approach in [5] at the high SNR region when the presence of unoccupied channels is rare.

There are numerous existing works considering the problem of spectrum sensing in both sequential and non-sequential manner. Matched filtering, energy detection [14], [15] and cyclostationary feature detection [16]–[18] are most commonly adopted non-sequential methods. Among the works on non-sequential spectrum sensing, we particularly mention that [19] also proposes a two-stage sensing strategy for a wideband cognitive radio system: the cognitive radio system firstly estimates the status of each band and then performs detection to test suspected bands found by the first stage. However, different from our work, the strategy proposed in [19] is a non-sequential strategy under OFDM signal model and dose not involve mixed observations. There are also extensive works consider the problem of sequential spectrum sensing. For example, recent paper [20] considers the multi-band spectrum sensing problem in which the cognitive radio system sequentially observers a group of correlated channels and aims to find an unoccupied one from them. [21] proposes to use adaptive sensing method to find a given number of spectrum holes from wide spectrum resource. [22]–[24] consider the problem of sequential cooperative spectrum sensing. In their frameworks, multiple secondary users individually collect their local channel information and send it to a fusion center, which combines all local statistics and makes a final decision, in a sequential manner. Different from these works, the unique feature of our paper is that a two stage sensing strategy is considered and a linear combination of channels is observed in the first sensing stage. [25] is a recent survey that provides an overview of spectrum sensing techniques and their property. We also note that some other signal processing technique, such as rare event detection [26] and outlier detection [27], [28], can be also potentially applied into the spectrum sensing problem. Similarly, although our work is originally motivated by the cognitive radio system, the proposed method can be potentially adopted by other applications such as database searching, sensor network, etc. Therefore, instead of considering some special distributions, our problem is formulated and derived with general distributions f0 and f1. We also note that some existing works [22] consider wide-band receivers which can collect samples from all candidate bands simultaneously. However, wide-band receivers usually involve high system complexity and high cost since they typically require high speed analog-to-digital converters and extra signal processing elements. Hence, narrow-band receivers are usually of practical interest.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section II formulates the mixed sensing strategy. Section III presents the optimal solution. A low complexity mixed sensing algorithm is proposed and its asymptotic performance is analyzed in Section IV. Numerical examples are provided in Section V. Finally, Section VI offers concluding remarks.

II. Problem Formulation

The secondary user has an infinite number of potential wireless channels, which are indexed by s = 1, 2, …. Let {, k = 1, 2, …} be the discrete time signal in channel s. The distribution of its samples obeys one of the following two hypotheses:

where f0 is the probability density function (pdf) when channel is unoccupied, and f1 is the pdf when channel is occupied. Let P0 and P1 be the probability measures that associates to f0 and f1, respectively. We assume that H0 has prior probability π0 and H1 has prior 1 − π0. Our goal is to find one channel generated by f0 as quickly and reliably as possible for the Secondary User to transmit its signal.

[5], [29] considers the scenario that the sensor observes one channel at each time slot. In this paper, we propose a new sequential sensing strategy, termed as mixed observation sensing strategy, for the multi-band spectrum sensing problem. This proposed strategy consists of two stages, namely the scanning stage and the refinement stage.

In the scanning stage, the sensor picks two channels and at each time slot k and observes a linear combination of signals from these two channels:

| (1) |

Since and have no difference in their distribution, we simply set the same weight a1 = a2 = 1 in this paper. We notice that this choice may not be optimal since in general a1 and a2 can be updated adaptively at every time slot based on the previous observations. Hence, to optimize the linear combination is one of our future research directions. In this paper, we focus on the setting a1 = a2 = 1 and we show that even this simple setting can bring significant improvement when the occurrence of f0 is rare.

Since each channel has two possible pdfs, Zk has three possible pdfs: 1) g0 ≔ f0 * f0, which happens when both channels and are unoccupied. Here * denotes the convolution. The prior probability of this occurring is ; 2) g1 ≔ f0*f1, which happens when one of these two channels is unoccupied. The corresponding prior probability is ; and 3) g2 ≔ f1 * f1, which happens when both channels are occupied. The prior probability is . Here, we use g to represent the pdf of Zk, and use the subscript of g to denote the number of occupied channels.

Denote ℱk as the set of observations in the scanning stage until time k, i.e., ℱk = {Z1, ⋯, Zk}. After taking sample Zk, the sensor needs to make one of the following three decisions: 1) to continue the scanning stage and to take one more observation from these two currently observing channels; or 2) to continue the scanning stage but to take observation from two other channels, that is, the sensor discards the currently observing channels and switches to observe two new channels; or 3) to stop the scanning stage and to enter the refinement stage to further examine these two candidate channels. Hence, there are two decisions involved in the scanning stage: the stopping time τ0, at which the sensor stops the scanning stage and enters the refinement stage, with respect to {ℱk}; and the channels switching rule ϕ = (ϕ1, ϕ2, ⋯), based on which the sensor abandons the currently observing channels and switches to observe new channels. Here, the element ϕk ∈ {0, 1} denotes the channel switching status at time slot k. Specifically, if ϕk = 1, the sensor switches to new channels, while if ϕk = 0, the sensor keeps observing the current two channels. ϕk is a function of ℱk.

In this proposed strategy, we emphasize that once the sensor enters the refinement stage, it could not come back to the scanning stage anymore. Hence the sensor will not enter the refinement stage until he is confident that at least one of the observing channels is unoccupied.

In the refinement stage, the samples are taken from one of the two candidate channels selected in the scanning stage. Hence, at this stage, no mixing is used anymore. Denote {Xj, j = 1, 2, …} as observation channel in this stage. At the beginning of the refinement stage, there is no difference between these two candidates and , and hence the sensor simply picks :

| (2) |

After taking each sample, the sensor needs to decide whether or not to stop the refinement stage. If so, he should pick one channel from and , and claim that it is unoccupied. Intuitively, if the sensor believes that the observed channel is unoccupied, then he claims . Otherwise, he claims . Hence, at the end of the refinement stage, one of the candidate channels must be selected to be unoccupied channel. Let 𝒢j ≔ {Z1, ⋯, Zτ0, X1, ⋯, Xj}. Denote τ1 as the time when the sensor stops the refinement stage, hence, τ1 is a stopping time with respect to {𝒢j}. Denote δ as the terminal decision rule, according to which the sensor selects the unoccupied channel.

We are interested in the average sensing delay (ASD) and false identification probability (FIP). In particular, these two performance metrics are defined as

respectively. The subscript “m” stands for the mixed observation sensing strategy. In this paper, we aim to solve the following optimization problem

| (3) |

III. Optimal Solution

In this section, we discuss the optimal solution for the proposed mixed observation sensing strategy. We first introduce some important statistics used in the optimal solution.

For the scanning stage, after taking k observations, we define the following posterior probabilities:

At the beginning of the scanning stage we have and . Let . It is easy to check that pk satisfies the Markov property. In particular,

where g(pk, Zk+1) and g(p0, Zk+1) are defined as

For the refinement stage, after taking j observations, we define the following posterior probabilities:

At the beginning of the refinement stage, we have and . It is easy to verify that these statistics can be updated using

Hence satisfies the Markov property. For the brevity of notation, we further define the following two statistics

| (4) |

| (5) |

Using the above defined statistics, we first have the following theorem about the optimal terminal decision rule:

Theorem III.1

For any τ0, ϕ and τ1, the optimal terminal decision rule is given as

| (6) |

and the corresponding cost is given as

| (7) |

Proof

Please see Appendix A.

Hence, the optimal decision rule is to pick the channel with the larger posterior probability. This theorem converts the cost of FIP into a function of q1,τ1 and q2,τ2. In the following, we decompose (3) into two concatenated single stopping time problems.

Lemma III.2

Let

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

Then

Proof

Please see Appendix B.

ϑ(τ0, ϕ) and u0 can be viewed as the cost functions in the refinement stage and in the scanning stage, respectively. In particular, Lemma III.2 indicates that (8) can be solved by two steps: we first solve τ1 for any given τ0 and ϕ, and then solve τ0 and ϕ under the optimal τ1. The optimal stopping rule for the refinement stage is given as:

Theorem III.3

For any given τ0 and ϕ,

in which V(·) is a function that satisfies the following recursion:

In addition, the optimal stopping time τ1 for (9) is given as

Proof

Please see Appendix C.

Besides the optimal stopping rule in the refinement stage, this theorem also indicates that the total cost of the refinement stage are related to τ0, ϕ only through , since

Hence, in the following we denote ϑ(τ0, ϕ) as .

The domain of is written as

Lemma III.4

υ (p0,0, pmix) is a concave function over 𝒫 with υ(1, 0) = 0 and υ(0, 0) = 1.

Proof

Please see Appendix C.

As the result, (10) can be written as

and its optimal solution is given as

Theorem III.5

The optimal stopping rule for the scanning stage is given as

| (11) |

and the optimal switching rule is given as

| (12) |

in which, U(·) is a function that satisfies the following operator

with

Proof

Please see Appendix D.

One can show that , hence it is a constant between 0 and 1. For this reason, we denote it as Φs rather than .

The optimal solutions, and , can be further simplified.

Lemma III.6

Φc (p0,0, pmix) and U (p0,0, pmix) are positive concave functions over 𝒫.

Proof

Please see Appendix D.

Since both U (p0,0, pmix) and υ (p0,0, pmix) are concave functions over 𝒫, U (p0,0, pmix) ≤ υ (p0,0, pmix) over 𝒫, and U(1, 0) = υ(1, 0) = 0, there must exist a certain region, denoted as Rτ, in which these two concave surfaces are equal to each other. Hence, the optimal stopping time can be described as the first hitting time of the process to the region Rτ. Similarly, Φc is a concave surface and Φs is a constant plane with . Hence, 𝒫 can be divided into two connected regions Rϕ and 𝒫\Rϕ, where Rϕ ≔ {(p0,0, pmix) : Φc (p0,0, pmix) > Φs}. Hence, the sensor switches to new channels at time slot k if is in Rϕ. As a result, we have the following theorem:

Theorem III.7

There exist two regions, Rτ ⊂ 𝒫 and Rϕ ⊂ 𝒫, such that

| (13) |

and

| (14) |

Figure 2 provides an illustration for the theoretical results obtained in this section. In particular, Figure 2 (a) is an illustration of the refinement stage cost function υ (p0,0, pmix). Note that υ(1, 0) = 0, whose physical meaning is that the sensor makes no decision error if , i.e., if both and are unoccupied. Similarly, υ(0, 0) = 1 means that the sensor always makes an error decision if both candidate sequences are occupied.

Fig. 2.

An illustration of Theorem III.7. Sub-figures are calculated numerically by setting f0 and f1 to be 𝒩(0, 1) and 𝒩(0, 3), respectively, and choosing parameter π0 = 0.05, c = 0.01.

Figure 2 (b) is an illustration of the overall cost function U (p0,0, pmix). Note that this function is flat at the top since it is upper bounded by a constant c + Φs. This flat area corresponds to Rϕ. Moveover, U (p0,0, pmix) is upper bounded by υ (p0,0, pmix). The overlap region of these two concave functions is the region Rτ. The locations of Rϕ and Rτ are illustrated in Figure 2 (c). The left-lower half below the black solid line is the domain 𝒫. The region circled by the red dash line is the channel switching region Rϕ, and the region circled by the blue dot-dash line is the scanning stop region Rτ. In this example, Rτ has two separate regions located around (0, 1) and (1, 0) respectively. Rτ and Rϕ can be computed offline.

IV. A Low Complexity Algorithm For The Mixed Sensing Strategy

The optimal solution obtained by DP has a very complex structure. In this section, we purpose a low complexity sensing algorithm and analyze its asymptotic performance when H0 is rare. In particular, we aims to characterize the asymptotic expression of ASDm(τ0, ϕ, τ1, δ) under a false identification constraint FIPm(τ0, ϕ, τ1, δ) ≤ ζ as π0 approaches to zero.

A. A Low Complexity Algorithm

The proposed low complexity strategy adopts CUSUM in the scanning stage and adopts SPRT in the refinement stage. Specifically, in the scanning stage, we use

| (15) |

where p̃k is computed recursively using the following formula

| (16) |

In the refinement stage, we use

| (17) |

Here q1,j is defined in (4), pL, qL, qU are pre-designed constant thresholds. The selection of these three thresholds will be discussed in the sequel. Note that the threshold in ϕ̃k is a fixed constant .

From Section III, we know that q1,0 is the sum of and , which are determined by and . However, in the scanning stage, the proposed algorithm does not contain these two statistics. In the following derivations, we treat q1,0 as an arbitrary value within (0, 1). For the implementation purpose, we can simply set q1,0 = 1/2. This choice will be justified in Lemma IV.2, which shows that the initial value of q1,0 does not significantly affect the sensing delay in the refinement stage.

A useful insight is that the above proposed low complexity algorithm can be expressed equivalently in terms of likelihood ratios. For the refinement stage, it is easy to verify that

Hence we have

| (18) |

where Lr is the likelihood ratio (LR) in the refinement stage. Hence, q1,j and Lr(X1:j) have a one-to-one mapping for any given q1,0. For the scanning stage, we define

| (19) |

Hence, Sk is a statistic which is equivalent to p̃k used in the scanning stage. By (16), it is easy to verify that on the event {ϕk = 0},

| (20) |

where Ls(Zk) ≔ g1(Zk)/g2(Zk) is the LR in the scanning stage. Similarly, on the event {ϕk = 1}, we can obtain

| (21) |

Hence

| (22) |

is the CUSUM statistic, where (a) is due to the channel switching rule defined in (23). Therefore, the proposed strategy in (15) and (17) can be equivalently written as

| (23) |

| (24) |

in which the thresholds are given as

Based on the above discussion, an intuitive explanation of the proposed strategy is given as follows: in the scanning stage, the sensor is supposed to do the following ternary simple hypothesis test at each time slot:

where P0,0, Pmix and P1,1 are the probability measures with probability densities g0, g1 and g2, respectively. The proposed scheme converts the trinary hypothesis test into a composite binary hypothesis test that H1,1 versus {Hmix, H0,0}. Since Hmix is closer to H1,1, we use the worst case likelihood ratio g1/g2 in the test. The sensor switches to observe the new channels if the test result favors H1,1. Otherwise, the sensor enters the refinement stage. In the refinement stage, the sensor examines only one channel, and there are only two possible outcomes: H0 and H1. In the proposed low-complexity scheme, the sensor adopts SPRT to examine sequentially. Then the sensor picks if the test favors H0 and picks if the test favors H1.

B. Asymptotic Analysis of the Proposed Low Complexity sensing Strategy

In this subsection, we study the performance of ASD when the presence of f0 is rare. We emphasize that the asymptotic analysis is in the sense π0 → 0 rather than ζ → 0.

For the scanning stage, we define the following stopping time

Stopping time τ̃0 can also be viewed as a renewal process, with each renewal occurring whenever p̃k is reset to , and with a termination occurring whenever p̃k exits the lower bound PL, hence we denote

where ηm,1, …, ηm,n, … are i.i.d. repetition of ηm, and N is the number of repetition. It is easy to see that N is geometrically distributed:

| (25) |

where χ0 is the event that the sensor switches to observe new channels, i.e., . Since {ηm,n} are i.i.d. repetition of ηm, we can only focus on the analysis of statistics for k = 1, …, ηm. Let

| (26) |

be a random walk in the scanning stage. Note that χ0 can be equivalently written as {Wηm < 0}. In the scanning stage, we further define

It is easy to verify that

In the refinement stage, we denote

αsprt ≔ P( is selected to be unoccupied| is occupied),

γsprt ≔ P( is selected to be occupied| is unoccupied)

as Type I error and Type II error of SPRT, respectively. We first have the following lemma about the selection of thresholds:

Lemma IV.1

| (27) |

is a set of thresholds that satisfy the FIP constraint.

Proof

Please see Appendix E.

In the following, we analyze the asymptotic ASD under two cases: 1) the fixed identification error (FIE) case, i.e., π0 → 0 while ζ is a constant in (0, 1). By Lemma IV.1, we have |log Bs| = |log π0|(1 + o(1)); 2) the rare identification error (RIE) case, i.e., π0 → 0 and ζ → 0. In this case, we have |log Bs| = (|log π0| + |log ζ|)(1 + o(1)). Let ρm = αm/π0. By (45), it is easy to see that ρm is a constant in the FIE case and ρm → 0 in the RIE case.

We first consider the delay caused in the refinement stage. For the FIE case, the thresholds qL and qU for SPRT are constants since ζ is a constant within (0, 1). Therefore, in this case the expected delay is finite, i.e., 𝔼q1,0 [τ1] < ∞. For the RIE case, we have the following lemma on the delay in the refinement stage:

Lemma IV.2

If ζ → 0, then for any given q1,0 ∈ (0, 1),

Proof

From (27) we know that qL → 0 and qU → 1 as ζ → 0. Then the Type I error and the Type II error of SPRT in the refinement stage can be approximated by ([30], Proposition 4.10):

Since both αsprt and γsprt are on the order of O(ζ), the delay caused by SPRT is given as ([30], Proposition 4.11):

where an ~ bn means that lim an/bn = 1. Since 𝔼q1,0[τ1] is a linear combination of 𝔼0[τ1] and 𝔼1[τ1], we have

Therefore

As we can see from the above lemma, if ζ → 0, the asymptotic delay in the refinement stage is determined by ζ, regardless of the value of q1,0. On the other hand, if ζ is a constant within (0, 1), the delay in the refinement stage is a finite value for any q1,0 ∈ (0, 1). Hence, for both cases, we can simply set q1,0 = 1/2 in implementation. As we will show later, compared with the delay in the scanning stage, the delay in the refinement stage is negligible.

The following lemma characterizes the delay incurred in the scanning stage.

Lemma IV.3

If 0 < D(g1||g0) < ∞ and 0 < 𝔼1,1[log(g1/g2)] < ∞, then as π0 → 0, the scanning stage delay for the FIE case is given as

| (28) |

In addition, if π0|log ζ| → 0, then the scanning stage delay for the RIE case is given as

| (29) |

Proof

Please see Appendix F.

Remark IV.4

In the above lemma, we make an additional assumption that π0|log ζ| → 0 to limit the speed of ζ approaching zero for the RIE case. This condition could be easily satisfied. For example, when ζ goes to zero on the order for any n < ∞, this condition still holds.

Observe that the scanning stage delay is on the order of , while the refinement stage delay is either a finite number (under the FIE case) or on the order of O(|log ζ|) (under the RIE case). Since π0|log ζ| → 0, we conclude that ASD is dominated by the detection delay in the scanning stage. Then, we obtain the following result immediately.

Theorem IV.5

With the assumptions in Lemma IV.3, as π0 → 0, we have

To further analyze ASD, one needs to characterize αm, βm and 𝔼0,0[ηm]. These quantities depend on the undershoot of the random walks crossing the lower bound. Existing works [31]—[33] on such problem focus on the case when the lower bound goes to zero. These results cannot be used in our paper since the lower bound As is constant 1. However, these quantities can be efficiently estimated by numerical methods.

Remark IV.6

The conclusion that the scanning stage delay dominates the refinement stage delay as π0 → 0 is a very important insight we gain from the two-observation mixed sensing strategy. The sensor may make two kinds of errors in the scanning strategy. The first kind of error is that the sensor enters the refinement stage with two occupied channels; the second kind of error is that at least one of observing channels is unoccupied but the observer abandons these two observing channels and switches to observer two new channels. The first kind of error will contribute to the false identification probability and the second kind of error will incur a longer detection delay in the scanning stage. Intuitively, to maintain a low identification error, the sensor needs to make sure that at least one of the two candidate channels selected in the scanning stage is generated from f0 since the sensor cannot move back to the scanning stage from the refinement stage. In other words, the mistake made in the scanning stage cannot be compensated in the refinement stage. Hence, the sensor will make the first kind of error under control (less than the required FIP constraint) at the expanse of bearing a larger second kind of error. As a result, the detection delay in the scanning stage, which turns out to be in proportion to , dominates the detection delay in the refinement stage.

Remark IV.7

It is of interest to compare the performance of the searching strategy in [5] with the result in Theorem IV.5. Since CUSUM is shown to be optimal in [5] for the case when no mixing observation is used, by using the similar methods in the proofs of Lemma IV.1 and Lemma IV.3, we can obtain the asymptotic performance of the strategy in [5]. In particular, by controlling FIP no larger than ζ, as π0 → 0, the ASD for the strategy in [5] is given as

| (30) |

in which ρs ≔ αs/π0, αs ≔ 1 − P1(χ0), βs ≔ P0(χ0) and , where πk and are the posterior probability and the upper bound of the CUSUM test defined in [5], respectively. In some special case interested in the cognitive radio system, the proposed mixed strategy can save a half of the sensing time. For example, let f0 be 𝒩(0, σ2) and f1 be 𝒩(μ, σ2). It is easy to show that both βs and βm approach to 0, and both 𝔼1[ηs] and 𝔼1,1[ηm] approach to 1 as μ → ∞. For the RIE case, in which ρs → 0 and ρm → 0, the delay ratio ASDm/ASDs approaches to 0.5.

At the end of this section, we comment that the proposed mixed observation sensing strategy can be easily extended to multiple stages. For example, we can propose a strategy which consists of one scanning stage and K refinement stages. Specifically, in the scanning stage, the sensor observes the sum of samples from 2K channels. After taking each observation, the sensor has to make one of the following three decisions: 1) to take another observation from the same group of channels; 2) to switch to another group of 2K channels; or 3) to stop scanning and enter the first refinement stage. Hence, there are 2K candidate channels for the first refinement stage. Each refinement stage selects half of the candidate channels for the next refinement stage. Specifically, the ith refinement stage, i = 1, …, K, has 2K−t+1 candidate channels, and the sensor divides them equally into two groups. Then the sensor observes the sum of samples from the channels in the first group. After taking each observation, the sensor has to make one of the following two decisions: 1) to take another observation from the first group; or 2) to stop the ith refinement stage and select one of the two groups for the next refinement stage. Hence, there are 2K−i candidate channels left after the ith refinement stage. When i = K, i.e., after the last refinement stage, there is only one channel left, which will be selected as unoccupied channel. This procedure can be modeled as a multiple stopping time problem with K + 1 stopping times. This multi-stage strategy can be solved similarly to our two-stage problem.

V. Simulation

In this section, we give some numerical examples to illustrate the performance proposed mixed observation sensing strategy in the cognitive radio system. In particular, we assume that for the unoccupied channels and for the occupied channels, in which Nk is white Gaussian noise with zero mean and σ2 variance. Sk is a demodulated BPSK signal with power P. We define the signal to noise ratio as SNR = 10 log(P/σ2).

We first study the relationship between ASD and SNR. In this simulation, we compare the performances of the optimal single observation strategy of [5], the optimal mixed observation strategy proposed in Section III and the low complexity mixed observation strategy proposed in Section IV. The average sensing delays of these three cases are named as ASDs, and ASDm, respectively. In the simulation, we choose π0 = 0.05 and control FIP to be around 0.005. The simulation result is shown in Figure 3, in which the red dash line with cross, green dot-dash line with squares and the blue solid line with circles are , ASDm and ASDs, respectively. The black dot line with triangulares is the simulation result of the performance bound presented in Theorem IV.5. As we can see, the detection delay of all these three strategies decreases as SNR increases. outperforms ASDs through the whole scale, the delay ratio decreases from 0.7 to 0.55 as SNR increases under this simulation setting. For the low complexity strategy, ASDm does not exhibit advantages over ASDs when SNR is small. A small SNR indicates that the KL divergence between f1 and f0 is small, the procedure of mixing observations will further lead to an even smaller KL divergence between g1 and g2. Since the scanning stage adopts the worst case likelihood ratio g2/g1 with a threshold rule, the small KL divergence causes a large detect delay in the scanning stage. As SNR increases, ASDm approaches to and can save about 45% sensing time compared to the single observation strategy.

Fig. 3.

ASD vs. SNR when π0 = 0.05, FIP ≈ 0.005

The second simulation illustrates the performance of ASD with respect to prior probability π0. In this simulation, we compare the performances of the optimal single observation strategy, the low complexity mixed observation strategy (mixing two channels), and the extended mixed observation strategy with four mixing channels discussed at the end of Section IV. The average sensing delays of these three cases are denoted as ASDs, ASDm,K=1 and ASDm,K=2, respectively. In addition, we denote rK=1 ≔ ASDm,K=1/ASDs and rK=2 ≔ ASDm,K=2/ASDs as delay ratios. The simulation result for SNR= 8dB is shown in Figure 4. The blue solid line with circles, the green dot-dash line with squares and the red dash line with crosses are ASDm,K=2, ASDm,K=1 and ASDs, respectively. From the figure we can see, when π0 is large, the mixed observation strategy does not have any advantages. Actually, in this case the performance of the single observation sensing strategy is slightly better than that of the mixed observation strategy. When most of potential channels are unoccupied, the sensor does not need to switch the observing channel frequently; hence the sensor could observe the channel one by one. In this case, a second stage strategy is redundant. However, when π0 is small, i.e., the majority of the channels are occupied, the mixed sensing strategy has advantage since it skips through the channels with distribution f1 more efficiently. Note that this figure is drawn on a logarithmic coordinate, ASDs and ASDm,K=1 are parallel to each other when π0 is small indicates that the delay ratio rK=1 approaches to a constant. Similar scenario happens to the strategy of mixing four channels. The advantage of mixing four channels is only exhibited under the case of small prior probability π0. Some numerical results are listed in Table I. From the table we can see delay ratios approaches to 0.5 and 0.3 for the two channel mixing strategy and four channel mixing strategy respectively.

Fig. 4.

ASD vs. π0 when SNR = 8dB, FIP ≈ 0.005

TABLE I.

ASD under different prior probabilities when SNR = 8dB

| Prior π0 |

Average sensing delay | Delay Ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASDs | ASDm,K = 1 | ASDm,K = 2 | rK = 1 | rK = 2 | |

| 0.5 | 2.0434 | 3.113 | 5.926 | 1.523 | 2.900 |

| 0.1 | 10.0052 | 6.95512 | 8.71500 | 0.6951 | 0.8710 |

| 0.01 | 100.847 | 50.5327 | 35.6015 | 0.5011 | 0.3530 |

| 0.001 | 997.933 | 568.417 | 323.085 | 0.5695 | 0.3237 |

| 0.0001 | 9988.33 | 5040.43 | 2997.49 | 0.5046 | 0.3001 |

VI. Conclusion

In this paper, a sequential multi-band spectrum sensing problem has been considered. A two-stage mixed-observation sensing strategy has been proposed. Correspondingly, the problem has been formulated as an optimal multiple stopping time problem. We have solved this problem by decomposing the problem into an ordered two concatenated Markov stopping time problem. The optimal solution has been characterized. Unfortunately, the optimal solution has a rather complex structure. We have proposed a low complexity algorithm, in which CUSUM is adopted in the scanning stage and SPRT is adopted in the refinement stage. The asymptotic performance of the low complexity algorithm has been analyzed. When the presence of unoccupied channels is rare, the proposed low complexity sensing strategy can significantly reduce the sensing delay.

Acknowledgments

The work of J. Geng was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities under grant AUGA5710013915. The work of L. Lai was supported by the National Science Foundation under grant CNS-14-57076.

Biographies

Jun Geng (S’13-M’15) received the B. E. and M. E. degrees from Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China in 2007 and 2009 respectively, and the Ph.D. degree from Worcester Polytechnic Institute, MA, United States in 2015. Since June 2015, he has been an associate professor at Harbin Institute of Technology. Dr. Geng’s research interests include stochastic signal processing, wireless communications and other related areas.

Weiyu Xu (M11) received his B.E. in Information Engineering from Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications in 2002, and a M.S. degree in Electronic Engineering from Tsinghua University in 2005. He received a M.S. and a Ph.D. degree in Electrical Engineering in 2006 and 2009 from HERE California Institute of Technology (Caltech), with a minor in Applied and Computational Mathematics. He is currently an Assistant Professor at the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the University of Iowa. His research interests are in signal processing, compressive sensing, communication networks, information and coding theory. Dr. Xu is a recipient of the Information Science and Technology Fellowship at Caltech, and the recipient of the Charles Wilts doctoral research award in 2010.

Lifeng Lai (M’07) received the B.E. and M. E. degrees from Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China in 2001 and 2004 respectively, and the PhD degree from The Ohio State University at Columbus, OH, in 2007. He was a postdoctoral research associate at Princeton University from 2007 to 2009, an assistant professor at University of Arkansas, Little Rock from 2009 to 2012, and assistant professor at Worcester Polytechnic Institute from 2012 to 2016. Since July 2016, he has been an associate professor at University of California, Davis. Dr. Lai’s research interests include information theory, stochastic signal processing and their applications in wireless communications, security and other related areas.

Dr. Lai was a Distinguished University Fellow of the Ohio State University from 2004 to 2007. He is a co-recipient of the Best Paper Award from IEEE Global Communications Conference (Globecom) in 2008, the Best Paper Award from IEEE Conference on Communications (ICC) in 2011 and the Best Paper Award from IEEE Smart Grid Communications (SmartGridComm) in 2012. He received the National Science Foundation CAREER Award in 2011, and Northrop Young Researcher Award in 2012. He served as a Guest Editor for IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications, Special Issue on Signal Processing Techniques for Wireless Physical Layer Security. He is currently serving as an Editor for IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications.

Appendix A

Proof of Theorem III.1

For i, j ∈ {0, 1}, let

Given τ0, ϕ, for any τ1, we have

Let PX be the conditional probability distribution of (X1, …, Xτ1) given (Z1, …, Zτ0); let be the conditional probability distribution of (X1, …, Xτ1) given both (Z1, …, Zτ0) and Ei,j. We have

can be calculated similarly. As a result, we can obtain

Note that P(Hδ = H1) = 𝔼[P(Hδ = H1|ℱτ0)]. It is clear that P(Hδ = H1) achieves its minimum when

Hence, infδ P(Hδ = H1) = 𝔼{1 − max{q1,τ1, q2,τ1}}.

Appendix B

Proof of Lemma III.2

The proof follows the reduction method proposed in [12] (Theorem 2.3 in [12]). For the brevity of notations, we define

Lemma B.1

{wk} is a submartingale.

Proof

Since wk is the essential infimum of a function, then there exist and such that . Then,

| (31) |

where (a) is due to the monotone convergence theorem.

We define

Note that the above definition is consistent with (10) when k = 0. In the following, we show wk = uk for all k = 0, 1, …. Since

we can obtain that wk ≥ uk by taking essinf on both sides of the inequality.

We next show that wk ≤ uk. Since

| (32) |

combining with Lemma B.1, we can conclude that wk is a submartingale dominated by ϑ̃ (k, ϕ). By the optimal stopping theorem, uk is the largest submartingale dominated by ϑ̃(k, ϕ). Hence wk ≤ uk. Therefore, we conclude that wk = uk.

Appendix C

Proof of Theorem III.3 and lemma III.4

We first consider a finite horizon refinement procedure, i.e. the refinement stopping time τ1 is restricted to a finite interval [0, T]. Then the problem

can be solved using the dynamic programming. In particular, we have

Lemma C.1

For each j, the function can be written as a function .

Proof

By (4) and (5), is a function of . Assuming that , we will show that . To this end, we only need to show is a function of .

That ends the proof.

Therefore, we have

Lemma C.2

is jointly concave over .

Proof

It is easy to see the domain of is convex, for j = 0, …, T. Moreover,

is jointly concave over . Assuming is a concave function, we are going to show that is a concave function.

It is easy to see that 1 − max{q1,j, q2,j} is a concave function. Therefore, we only need to show that is concave. Let and be two arbitrary points in the domain of , and let 0 ≤ λ ≤ 1, we have

| (33) |

where

| (34) |

and we have used the concavity of in writing the inequality.

Now, on defining rj,3 = λrj,1 + (1 − λ)rj, 2, we consider each element in rj, 3 separately. First, we have

| (35) |

where (a) is true because

| (36) |

and (b) is true because

From (36), we have

Similarly, we can obtain

and hence

By (33) we have

which means that is concave.

Since any stopping time in [0, T] is also in [0, T + 1], we have . As is lower bounded by 0, and rj is a homogenous Markov chain, the following limit is well defined

By the monotone convergence theorem, the cost-to-go function of the infinite horizon problem can be written as

By the optimal stopping theory, the optimal stopping time is given as

Since V preserves the concavity of is a concave function.

Appendix D

Proof of Theorem III.5 and Lemma III.6

We first consider a finite horizon scanning stage, that is the sensor must enter the refinement stage before some time T. Hence τ0 ∈ [0, T]. Throughout this proof, the refinement procedure has an infinite horizon. We first show that the problem (10) can be solved by the dynamic programming.

Lemma D.1

Let

Then , where

| (37) |

is the finite horizon cost function for the scanning stage with τ0 ∈ [0, T].

Proof

Define

where . Note that .

For k = T, the scanning stage has to stop immediately, hence τ0 = T,

Assuming that , we will show .

Since is defined as the minimal cost at the kth time slot, we immediately have . In the following, we show that . On the event {τ0 = k}, we have

| (38) |

On the event {τ0 ≥ k + 1}, we have

| (39) |

in which, (a) is true because

| (40) |

Since (38) and (39) hold for any ϕ, then we have

Therefore, we have for all k = 0, …, T, which further indicates .

Lemma D.2

For each k, the function can be written as a function .

Proof

To show this statement, it is suffice to show that

are functions of . This can be done using mathematical induction similar to Lemma C.1. Combining with the recursive form of pk, we can find is a function of , and is a function of . Hence is a constant. We omit the detailed proof for brevity.

Therefore, we have

| (41) |

Lemma D.3

For any k, is a bivariate concave function of .

Proof

To show this statement, it is suffice to show that the concavity of . This can be done using mathematical induction similar to Lemma C.2. Hence the detailed proof is omitted for brevity.

Since , and is lower bounded by 0. Moreover, and are homogenous Markov chains, hence the following limit is well defined.

| (42) |

By the dominant convergence theorem, the following limits are well defined

| (43) |

| (44) |

Taking limit on both sides of (41), we can obtain

Hence, the optimal stopping time is given as

and the optimal switch function is given as

Appendix E

Proof of Lemma IV.1

We first study the error probability in the scanning stage.

| (45) |

When the sensor enters the refinement stage, there are three possible cases, which are defined as follows

E1,1 is expected to have a small probability since it will always incur an identification error in the refinement stage. Because {ηm,n} is i.i.d. repetition of ηm, it is sufficient for us to consider the case of N = 1, i.e., the sensor enters the refinement stage at ηm,1. By Baye’s rule, it is easy to verify

By setting and using (45) we have

| (46) |

Then we study the error probability in the refinement stage. By the proposition of SPRT ([30], Proposition 4.10), we have

Hence, the probability that the sensor infers the state of incorrectly is

| (47) |

If we choose qL = (ζ/2)/(1 + ζ/2) and qU = 1/(1 + ζ/2), then we have

| (48) |

Note that this inequality holds for any value of q1,0.

Note that the sensor makes no identification error under E0,0 and makes no correct identification under E1,1. Under Emix, the the false identification probability is described in (48). Therefore, we have P(Hδ = H1|E0,0, N = 1) = 0, P(Hδ = H1|Emix, N = 1) < ζ/2 and P(Hδ = H1|E1,1, N = 1) = 1. As a result, we have

where (a) is because of the homogeneity of renewals.

Appendix F

Proof of Lemma IV.3

Since we have

| (49) |

where (a) is due to the Wald’s identity and (b) is because of the geometric distribution of N (25). In the following, we first study 𝔼0,0[ηm]. Recall . Since As = 1 and we have

At the same time, by Wald’s identity, we have

Then we have

Follow the same procedure, we can obtain

Note that π0|log Bs| → 0 for both FIE and RIE cases, hence and approach zero when π0 → 0. Therefore, by (49) we have

(29) follows from the fact that ρm → 0 in the RIE case.

Footnotes

The results in this paper were presented in part at IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Istanbul, Turkey, July, 2013.

Contributor Information

Jun Geng, School of Electronics and Information Engineering, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, 150001, China (jgeng@hit.edu.cn).

Weiyu Xu, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, 52242, USA (weiyu-xu@uiowa.edu).

Lifeng Lai, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of California, Davis, CA, 95616, USA (lfai@ucdavis.edu).

References

- 1.Kim SJ, Giannakis GB. Proc. Conf. on Information Science and Systems. Baltimore, MD: 2009. Mar, Rate-optimal and reduced-complexity sequential sensing algorithms for cognitive OFDM radios. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xin Y, Zhang H, Lai L. A low-complexity sequential spectrum sensing scheme for cognitive radio. IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications. 2014 Mar;32:387–399. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caromi R, Xin Y, Lai L. Fast multiband spectrum scanning for cognitive radio systems. IEEE Trans. Communications. 2013 Aug;61:63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wald A. Sequential tests of statistical hypotheses. Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1945;16:117–186. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai L, Poor HV, Xin Y, Georgiadis G. Quickest search over multiple sequences. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory. 2011 Aug;57:5375–5386. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Page ES. Continuous inspection schemes. Biometrika. 1954 Jun;41:100–115. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moustakides GV. Optimal stopping times for detecting changes in distribution. Annals of Statistics. 1986;14(4):1379–1387. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorfman R. The detection of defective members of large populations. Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1943 Dec;14:436–440. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donoho DL. Compressed sensing. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory. 2006 Apr;52:1289–1306. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Candes E, Tao T. Near optimal signal recovery from random projections: Universal encoding strategies? IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory. 2006 Dec;52:5406–5425. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carmona R, Dayanik S. Optimal multiple stopping of linear diffusions. Mathematics of Operations Research. 2008;31:446–460. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kobylanski M, Quenez M, Rouy-Mironescu E. Optimal multiple stopping time problem. Annals of Applied Probability. 2011;21(4):1365–1399. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christensen S, Irle A, Jrgens S. Optimal multiple stopping with random waiting times. Sequential Analysis: Design Methods and Application. 2013 Jul;32:297–318. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atapattu S. Energy detection based cooperative spectrum sensing in cognitive radio networks. IEEE Trans. Wireless Communications. 2011 Apr;10:1232–1241. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang W, Mallik RK, Letaief KB. Optimization of cooperative spectrum sensing with energy detection in cognitive radio networks. IEEE Trans. Wireless Communications. 2009 Dec;8:5761–5766. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Derakhshani M, Le-Ngoc T, Nasiri-Kenari M. Efficient cooperative cyclostationary spectrum sensing in cognitive radios at low SNR regimes. IEEE Trans. Wireless Communications. 2011 Nov;10:3754–3764. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lunden J, Koivunen V, Huttunen A, Poor HV. Collaborative cyclostationary spectrum sensing for cognitive radio systems. IEEE Trans. Signal Processing. 2009 Dec;57:4182–4195. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sutton PD, Nolan KE, Doyle LE. Cyclostationary signatures in practical cognitive radio applications. IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications. 2008 Jan;2:13–24. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hwang CH, Lai GL, Chen SC. Spectrum sensing in wideband OFDM cognitive radios. IEEE Trans. Signal Processing. 2010 Feb;58:709–718. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tajer A, Heydari J. Quickest wideband spectrum sensing over correlated channels. IEEE Trans. Communications. 2015 Jun;63:3082–3091. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tajer A, Castro RM, Wang X. Adaptive sensing of congested spectrum bands. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory. 2012 May;58:6110–6125. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim SJ, Giannakis GB. Sequential and cooperative sensing for multichannel cognitive radios. IEEE Trans. Signal Processing. 2010 Aug;58:4239–4253. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yilmaz Y, Moustakides GV, Wang X. Cooperative sequential spectrum sensing based on level-triggered sampling. IEEE Trans. Signal Processing. 2012 Sep;60:4509–4524. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zou Q, Zheng S, Sayed AH. Cooperative sensing via sequential detection. IEEE Trans. Signal Processing. 2010 Dec;58:6266–6283. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Axell E, Leus G, Larsson EG, Poor HV. State-of-the-art and recent advances spectrum sensing for cognitive radio. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine. 2012;29:101–116. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tajer A, Poor HV. Quickest search for rare event. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory. 2013 Mar;59:4462–4481. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tajer A, Veeravalli VV, Poor HV. Outlying sequence detection in large data sets: A data-driven approach. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine. 2014 Sep;31:44–56. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banerjee T, Veeravalli VV. Data-efficient quickest outlying sequence detection in sensor networks. IEEE Trans. Signal Processing. 2015 Jul;63:3727–3735. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malloy M, Tang G, Nowak R. The sample complexity of search over multiple populations. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory. 2012 Apr;59:5039–5050. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poor HV, Hadjiliadis O. Quickest Detection. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siegmund D. Sequential Analysis. New York: Springer; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lotov VI. On some boundary crossing problem for Gaussian random walks. Annals of Probability. 1996;24(4):2154–2171. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang JT, Peres Y. Ladder heights, Gaussian random walks and the Riemann zeta function. Annals of Probability. 1997;25(2):787–802. [Google Scholar]