Abstract

Groups of mice infected intravenously with Candida albicans were treated intraperitoneally with amphotericin B, caspofungin, or fluconazole, starting at intervals before and after challenge. Survival was longest and tissue burdens were most reduced with early treatment, and survival times fell proportionately as treatment was delayed, reinforcing clinical recommendations for the earliest possible initiation of antifungal therapy.

Guidelines for treatment of disseminated Candida infections have always emphasized the need for early implementation of antifungal therapy (12, 14). Amphotericin B, fluconazole, and caspofungin are first-line treatment choices, but their impact is reduced by the difficulties of accurate diagnosis of the disease (5, 8, 16). In practice, many, if not most, Candida infections are treated either empirically, when infection has progressed for several days without responding to antibacterial chemotherapy, or after blood cultures have become positive for a Candida species, which typically means a wait of 1 or 2 days. The consequences of late institution of antifungal chemotherapy for a patient with a disseminated Candida infection have never been systematically quantified. We therefore used a model of intravenous challenge of mice with Candida albicans, instituting treatment at different intervals relative to the time of challenge, to determine the difference in outcome that results from delayed implementation of therapy.

C. albicans strain SC5314, which is susceptible to amphotericin B at 0.25 μg/ml, to caspofungin at 0.063 μg/ml, and to fluconazole at 0.25 μg/ml, was maintained on Sabouraud agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom). Mouse challenge inocula were grown in NGY broth (neopeptone [Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.], 1 g/liter; yeast extract [Difco], 1 g/liter; and glucose, 4 g/liter) for 18 h at 30°C. The inocula were centrifuged, washed twice in sterile saline, reconstituted in saline, and counted with a hemocytometer. Female BALB/c mice (Harlan Laboratories, Bicester, United Kingdom) weighing 18 to 23 g were given food and water ad libitum and maintained under conditions approved by the United Kingdom Home Office laboratory animals inspectorate.

Two separate experiments were done. In one, a challenge dose of 2 × 104 CFU/g of body weight was given intravenously (i.v.) via the lateral tail vein; in the second, the challenge dose was 1 × 105 CFU/g. In our hands, these doses result in mean survival times of 7 to 8 days and 2 days, respectively, in untreated animals. All experiments were done with groups of 12 mice. The condition of the animals was monitored daily. Animals that became immobile or otherwise showed signs of severe illness were humanely terminated and recorded as dying on the following day. On postchallenge day 4, animals 11 and 12 from each group were humanely terminated, and C. albicans burdens were determined by viable counting of homogenates from the left kidney and the brain, which were removed aseptically. Viable count detection limits were 2.0 log10 CFU/g for the kidney and 1.8 log10 CFU/g for the brain. For organ homogenates that were culture-negative, a count of 0.5 log10 below these limits was assigned for the calculation of mean burdens for the whole group.

Amphotericin B (Fungizone) for injection, fluconazole (Diflucan) for injection, and caspofungin (Cancidas) powder for injection were purchased via the local hospital pharmacy, reconstituted according to the manufacturers' directions, and diluted in sterile saline to concentrations suitable for doses of 1 mg/kg (amphotericin B and caspofungin) or 10 mg/kg (fluconazole) in volumes of approximately 100 μl.

The experimental design involved administration of each of the three test agents by daily intraperitoneal (i.p.) dosing for a period of 7 days. Dosing regimens were started on days −1, 0, 1, 2, and 3 relative to the day of challenge (day 0) with 2 × 104 CFU of C. albicans/g and on days −1, 0, 1, and 2 relative to the day of challenge with 1 × 105 CFU of C. albicans/g. To ensure equivalent handling of all animals, i.p. injections were done for all groups from day −1 through day 10; on days before and after the 7-day period of treatment with antifungal agents, the animals were injected with saline. A control group was injected with saline from day −1 through day 10. Saline and antifungal treatments on the day of challenge (day 0) were given just prior to the i.v. inoculation.

Survival was monitored for animals 1 to 10 in each experimental group to 14 days for animals challenged with 1 × 105 CFU/g and to 21 days for animals challenged with 2 × 104 CFU/g. Organ burdens of C. albicans were determined for all animals at the time of their death or termination. Survival data were analyzed by Kaplan-Meier log rank tests, and mean organ burdens were calculated by Student's t test.

Challenge with 2 × 104 CFU/g.

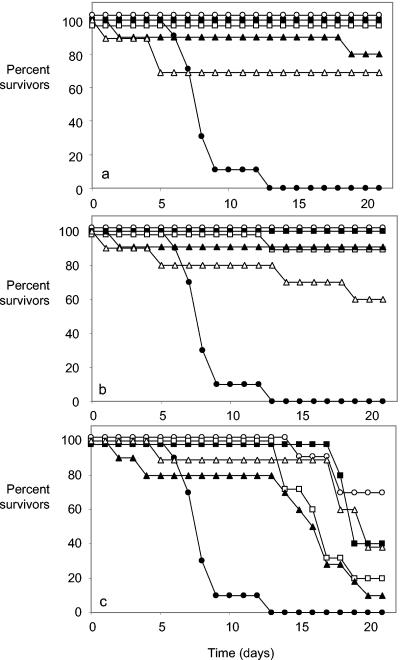

All animals that were treated with amphotericin B or caspofungin (1 mg/kg) starting on day −1, 0, or 1 relative to the day of challenge survived to the end of the experiment (on day 21), except for one mouse in the caspofungin group, which was treated from 1 day after challenge and survived to day 13 (Fig. 1). When amphotericin B or caspofungin treatment began on postchallenge day 2 or 3 (Fig. 1A and B) or fluconazole treatment began on day 1, 2, or 3 (Fig. 1C), the numbers of animals surviving to day 21 fell progressively.

FIG. 1.

Survival of mice infected i.v. with a challenge dose of 2 × 104 CFU of C. albicans/g and treated with (a) amphotericin B (1 mg/kg/day), (b) caspofungin (1 mg/kg/day), and (c) fluconazole (10 mg/kg/day). Filled circles, placebo treatment only; open circles, treatment started on day −1; filled squares, treatment started on day 0; open squares, treatment started on day 1; filled triangles, treatment started on day 2; open triangles, treatment started on day 3. When data points overlapped, they were adjusted by 1 or 2% from actual values to make all curves visible.

Mean survival times for all groups of treated mice were significantly prolonged compared to those of controls, except when amphotericin B treatment began 3 days after challenge (Table 1). However, mean survival times tended to fall, and the P value for the log rank statistic generally rose, with each day after challenge that treatment was started. Among amphotericin B-treated mice, kidney burdens at the time of termination were undetectable for all but one of the animals when treatment started on day −1, 0, 1, or 2, but they were detectable in 4 of the 10 animals whose treatment began on day 3 (Table 1). C. albicans-positive brain cultures were also predominantly negative for amphotericin B-treated mice, except for the group of animals whose treatment started on day 3. Mean kidney and brain burdens were significantly reduced relative to placebo-treated animals in all amphotericin B-treated mice (Table 1). The tissue burden data for caspofungin-treated mice followed a trend similar to that for the amphotericin B-treated animals (Table 1). Regardless of the time at which caspofungin treatment was started, the brain and kidney burdens were significantly lower than those in placebo-treated animals. However, in the caspofungin-treated animals, the mean kidney burdens increased progressively with each day's delay of treatment after the day of challenge (Table 1). In mice treated with fluconazole, kidney burdens remained fairly high regardless of the day on which treatment started; none of the mean burdens was significantly lower than in placebo-treated mice. Brain burdens in fluconazole-treated animals were significantly reduced from control values when treatment was started up to 2 days postchallenge, but there was no reduction in brain burdens when treatment started on day 3 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Outcome of antifungal treatment in experimental murine C. albicans infection with a challenge dose of 2 × 104 CFU/ga

| Treatment | Treatment start dayb | Mean ± SD (P value) for:c

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival (days) | Kidney (log CFU/g) at demise (n = 10) | Brain (log CFU/g) at demise (n = 10) | Kidney (log CFU/g) on day 4 (n = 2) | Brain (log CFU/g) on day 4 (n = 2) | ||

| Placebo | 8.3 ± 1.8 | 6.5 ± 1.6 | 4.5 ± 1.4 | 5.1 ± 0.7 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | |

| AMB | −1 | 21 ± 0.0 (<0.001) | 1.5 ± 0.3 (<0.001) | 1.3 ± 0.3 (<0.001) | 2.8 ± 0.0d (0.065) | 3.2 ± 0.3 (0.033) |

| AMB | 0 | 21 ± 0.0 (<0.001) | 1.5 ± 0.3 (<0.001) | 1.4 ± 0.6 (<0.001) | 3.6 ± 0.5 (0.068) | 3.4 ± 0.1d (0.064) |

| AMB | 1 | 21 ± 0.0 (<0.001) | 1.8 ± 0.9 (<0.001) | 1.3 ± 0.3 (<0.001) | 4.0 ± 0.2d (0.12) | 3.8 ± 0.0d (0.144) |

| AMB | 2 | 18.9 ± 5.7 (<0.01) | 1.5 ± 0.4 (<0.001) | 1.6 ± 0.8 (<0.001) | 4.5 ± 1.1 (0.29) | 4.1 ± 0.3d (0.42) |

| AMB | 3 | 15.8 ± 8.0 (>0.05) | 2.8 ± 2.0 (<0.001) | 2.0 ± 1.5 (<0.01) | 4.6 ± 0.4d (0.24) | 4.5 ± 0.7d (0.33) |

| CFN | −1 | 21 ± 0.0 (<0.001) | 1.5 ± 0.3 (<0.001) | 1.3 ± 0.3 (<0.001) | 2.2 ± 0.1d (0.052) | 2.5 ± 0.4 (0.033) |

| CFN | 0 | 21 ± 0.0 (<0.001) | 1.5 ± 0.3 (<0.001) | 1.3 ± 0.3 (<0.001) | 2.9 ± 0.5 (0.037) | 2.9 ± 0.6 (0.087) |

| CFN | 1 | 20.2 ± 2.4 (<0.001) | 1.9 ± 1.0 (<0.001) | 2.0 ± 1.6 (<0.01) | 2.9 ± 0.3d (0.051) | 3.3 ± 0.1d (0.038) |

| CFN | 2 | 19.1 ± 5.7 (<0.01) | 2.5 ± 1.3 (<0.001) | 1.4 ± 0.6 (<0.001) | 4.9 ± 0.7 (0.41) | 3.8 ± 0.2d (0.13) |

| CFN | 3 | 16.5 ± 7.1 (<0.05) | 3.4 ± 1.7 (<0.01) | 2.3 ± 1.4 (<0.01) | 5.9 ± 0.7d (0.18) | 4.6 ± 0.5d (0.22) |

| FLC | −1 | 19.8 ± 2.0 (<0.001) | 5.3 ± 1.9 (>0.05) | 1.5 ± 0.8 (<0.001) | 3.5 ± 0.1d (0.09) | 3.7 ± 0.0d (0.1) |

| FLC | 0 | 19.6 ± 1.2 (<0.001) | 5.2 ± 2.4 (>0.05) | 2.4 ± 1.4 (<0.01) | 3.7 ± 0.1 (0.1) | 3.7 ± 0.0d (0.12) |

| FLC | 1 | 17.0 ± 2.5 (<0.001) | 6.2 ± 1.6 (>0.05) | 1.7 ± 1.1 (<0.001) | 4.3 ± 0.0d (0.17) | 3.5 ± 0.2d (0.047) |

| FLC | 2 | 14.5 ± 6.1 (<0.05) | 6.2 ± 1.5 (>0.05) | 2.5 ± 1.4 (<0.01) | 5.6 ± 0.0 (0.1) | 4.1 ± 0.0 (0.12) |

| FLC | 3 | 18.3 ± 4.6 (<0.01) | 6.6 ± 1.6 (>0.05) | 3.5 ± 1.4 (>0.05) | 5.9 ± 0.6 (0.17) | 4.4 ± 0.6 (0.3) |

Groups of 12 mice were used. AMB, amphotericin B; CFN, caspofungin; FLC, fluconazole.

Start day of treatment relative to day of infection. −1, treatment began the day before infection; 0, treatment began the day of infection; 1, 2, or 3, treatment began 1, 2, or 3 days after infection, respectively.

P values for days of survival are by the log rank test. P values for results for Kidneys and brains are by Student's t test comparing burdens with the placebo-treated group.

Significance difference (P < 0.05 in two-tailed Student's t test) with the equivalent burdens measured at the time of demise.

Mean kidney and brain burdens determined on day 4 of the experiment for two animals in each treatment group were seldom significantly lower than for placebo-treated mice, although they showed a clear trend towards higher burdens with increasing delay in initiation of treatment (Table 1). In animals that received amphotericin B or caspofungin, the 4-day burdens were often significantly higher than the mean burdens determined at the time of death or termination of the animals (Table 1). A similar correlation between mean burden on day 4 and the day treatment started was seen for animals treated with fluconazole (Table 1). However, in these animals, the kidney burdens tended to be lower on day 4 than at the time of death, while the brain burdens were higher.

Challenge with 105 CFU/g.

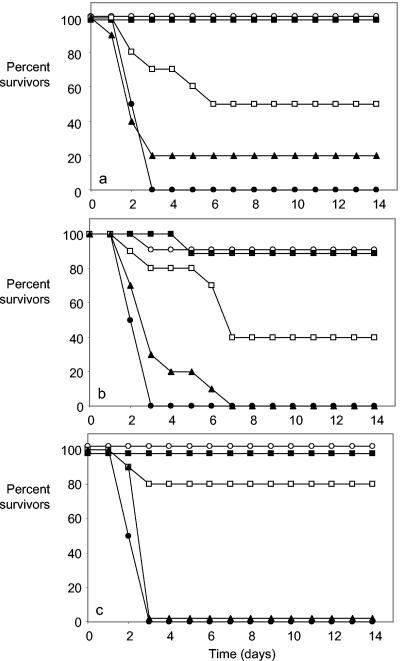

A trend towards lower survival and higher tissue burdens with each day's delay in starting antifungal treatment was also evident in mice challenged with an inoculum high enough to cause rapid disseminated infection. Kaplan-Meier curves (Fig. 2) showed that very few animals treated from day −1 or 0 relative to the day of challenge failed to survive to day 14, while animals whose treatment began on day 1 showed reduced mean survival times, although they were significantly prolonged relative to placebo treatment (Table 2). All placebo-treated mice and those whose fluconazole treatment started on day 2 failed to survive beyond day 3. Mean survival was slightly but not significantly prolonged among mice given amphotericin B or caspofungin starting on day 2 (Table 2).

FIG. 2.

Survival of mice infected i.v. with a challenge dose of 1 × 105 CFU of C. albicans/g and treated with (a) amphotericin B (1 mg/kg/day), (b) caspofungin (1 mg/kg/day), and (c) fluconazole (10 mg/kg/day). Filled circles, placebo treatment only; open circles, treatment started on day −1; filled squares, treatment started on day 0; open squares, treatment started on day 1; filled triangles, treatment started on day 2. When data points overlapped, they were adjusted by 1 or 2% from actual values to make all curves visible.

TABLE 2.

Outcome of antifungal treatment in experimental murine C. albicans infection with a challenge dose of 1 × 104 CFU/ga

| Treatment | Treatment start day | Mean ± SD (P value) for:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival (days) | Kidney (log CFU/g) at demise | Brain (log CFU/g) at demise | ||

| Placebo | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 6.5 ± 1.5 | 5.3 ± 1.3 | |

| AMB | −1 | 14.0 ± 0.0 (<0.01) | 1.5 ± 0.3 (<0.001) | 1.4 ± 0.5 (<0.001) |

| AMB | 0 | 14.0 ± 0.0 (<0.01) | 1.5 ± 0.3 (<0.001) | 1.3 ± 0.0 (<0.001) |

| AMB | 1 | 8.8 ± 5.3 (<0.05) | 4.0 ± 2.8 (<0.01) | 3.3 ± 2.2 (<0.05) |

| AMB | 2 | 4.5 ± 4.8 (>0.05) | 5.1 ± 2.8 (>0.05) | 3.9 ± 2.1 (>0.05) |

| CFN | −1 | 12.9 ± 3.3 (<0.01) | 1.7 ± 0.8 (<0.001) | 1.5 ± 0.7 (<0.001) |

| CFN | 0 | 13.1 ± 2.7 (<0.01) | 2.1 ± 1.3 (<0.001) | 1.8 ± 1.3 (<0.001) |

| CFN | 1 | 8.8 ± 4.5 (<0.05) | 3.3 ± 2.2 (<0.01) | 3.3 ± 2.2 (<0.01) |

| CFN | 2 | 3.5 ± 1.6 (>0.05) | 6.3 ± 1.8 (>0.05) | 5.0 ± 1.4 (>0.05) |

| FLC | −1 | 14.0 ± 0.0 (<0.01) | 4.0 ± 1.4 (<0.01) | 1.5 ± 0.5 (<0.001) |

| FLC | 0 | 14.0 ± 0.0 (<0.01) | 4.2 ± 1.4 (<0.01) | 1.8 ± 0.7 (<0.001) |

| FLC | 1 | 11.7 ± 4.6 (<0.05) | 5.2 ± 1.5 (>0.05) | 2.5 ± 1.7 (<0.01) |

| FLC | 2 | 2.9 ± 0.3 (>0.05) | 6.2 ± 1.6 (>0.05) | 4.5 ± 1.4 (>0.05) |

See footnotes a to d for Table 1.

The mean organ burdens of C. albicans at the time of termination (Table 2) were significantly reduced when amphotericin B and caspofungin treatment began up to 1 day after challenge. In mice given fluconazole on days −1 and 0, a significant reduction in brain and kidney burdens was achieved; however, when treatment began 1 day after challenge, only the brain burdens showed significant reductions from control levels (Table 2). None of the antifungal agents achieved significant reductions in any organ burdens when treatment began on postchallenge day 2. The early deaths of many mice meant that the day 4 burden data were incomplete; these results are therefore not shown.

On one level, the results of this study were predictable. The later treatment of an infection is delayed, the lower the chances for successful eradication of that infection. We have now, however, systematically quantified the consequences of delaying commencement of treatment of an experimental disseminated C. albicans infection both when the infection progressed steadily (2 × 104 CFU/g challenge) and when the infection progressed very rapidly (1 × 105 CFU/g challenge). In both situations, all three antifungal agents tested performed well, significantly prolonging survival and, particularly in the cases of amphotericin B and caspofungin, reducing tissue burdens of fungi. However, these therapeutic effects were maximal only when mice were treated before or very soon after the time of infection.

Our treatment doses for amphotericin B and caspofungin were based on fairly uniform literature reports of efficacies in tests with C. albicans infections in immunologically intact and immunosuppressed mice (1, 2, 4, 6, 9, 17). The fluconazole dose was less easy to choose since published reports show efficacy for a wide range of doses given i.p. in various mouse models of disseminated C. albicans infection (3, 4, 7, 10, 15), and our choice of 10 mg/kg was lower than optimal according to one pharmacokinetic study of fluconazole with mice (10).

In clinical practice, antifungal therapy is commonly started empirically several days after antibacterial drugs have been given, since bacterial infections are the most common cause of fever (11, 13). To the extent that data from animal experiments can be extrapolated to the clinical situation, our study shows that a wait of 3 to 4 days after onset of a fungal infection could seriously reduce the likelihood of treatment success, even when the infecting fungus is susceptible to the agent used. We consider our findings justification for considering the addition of antifungal treatment to antibacterial agents as soon as possible after the commencement of fever in a patient at risk whenever there is a possibility that the fever may be caused by a fungus rather than, or as well as, a bacterium. With agents of low toxicity, such as fluconazole and caspofungin, available for treatment of fungal infections, it should be possible to commence even empirical therapy of possible candidemias sooner rather than later.

Acknowledgments

D.M.M. is supported by the University of Aberdeen. The work of our laboratory is funded by grants from several bodies, including the Wellcome Trust, BBSRC, the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, and Merck & Co., Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abruzzo, G. K., A. M. Flattery, C. J. Gill, L. Kong, J. G. Smith, V. B. Pikounis, J. M. Balkovec, A. F. Bouffard, J. F. Dropinski, H. Rosen, H. Kropp, and K. Bartizal. 1997. Evaluation of the echinocandin antifungal MK-0991 (L-743,872): efficacies in mouse models of disseminated aspergillosis, candidiasis, and cryptococcosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2333-2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abruzzo, G. K., C. J. Gill, A. M. Flattery, L. Kong, C. Leighton, J. G. Smith, V. B. Pikounis, K. Bartizal, and H. Rosen. 2000. Efficacy of the echinocandin caspofungin against disseminated aspergillosis and candidiasis in cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppressed mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2310-2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arthington-Skaggs, B. A., D. W. Warnock, and C. J. Morrison. 2000. Quantitation of Candida albicans ergosterol content improves the correlation between in vitro antifungal susceptibility test results and in vivo outcome after fluconazole treatment in a murine model of invasive candidiasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2081-2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bannatyne, R. M., P. C. Cheng, and I. W. Fong. 1992. Comparison of the efficacy of cilofungin, fluconazole and amphotericin B in the treatment of systemic Candida albicans infection in the neutropenic mouse. Infection 20:168-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchheidt, D., H. Skladny, C. Baust, and R. Hehlmann. 2000. Current serological and molecular methods in the diagnosis of systemic infections with Candida sp. and Aspergillus sp. in immunocompromised patients with hematological malignancies. Antibiot. Chemother. (Basel) 50:59-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graybill, J. R., R. Bocanegra, L. K. Najvar, S. Hernandez, and R. A. Larsen. 2003. Addition of caspofungin to fluconazole does not improve outcome in murine candidiasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2373-2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikeda, F., Y. Wakai, S. Matsumoto, K. Maki, E. Watabe, S. Tawara, T. Goto, Y. Watanabe, Y., F. Matsumoto, and S. Kuwahara. 2000. Efficacy of FK463, a new lipopeptide antifungal agent, in mouse models of disseminated candidiasis and aspergillosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:614-618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalin, M., and B. Petrini. 1996. Clinical and laboratory diagnosis of invasive Candida infection in neutropenic patients. Med. Oncol. 13:223-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khardori, N., H. Nguyen, L. C. Stephens, L. Kalvakuntla, B. Rosenbaum, and G. P. Bodey. 1993. Comparative efficacies of cilofungin (Ly121019) and amphotericin B against disseminated Candida albicans infection in normal and granulocytopenic mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:729-736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Louie, A., P. Banerjee, G. L. Drusano, M. Shayegani, and M. H. Miller. 1999. Interaction between fluconazole and amphotericin B in mice with systemic infection due to fluconazole-susceptible or -resistant strains of Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2841-2847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyman, G. H. 2003. Risk assessment in oncology clinical practice. From risk factors to risk models. Oncology 17(Suppl. 11):S8-S13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pappas, P. G., J. H. Rex, J. D. Sobel, S. G. Filler, W. E. Dismukes, T. J. Walsh, and J. E. Edwards. 2004. Guidelines for treatment of candidiasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:161-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paul, M., K. Soares-Weiser, and L. Leibovici. 2003. β lactam monotherapy versus β lactam-aminoglycoside combination therapy for fever with neutropenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. Med. J. 329:1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rex, J. H., T. J. Walsh, J. D. Sobel, S. G. Filler, P. G. Pappas, W. E. Dismukes, and J. E. Edwards. 2000. Practice guidelines for the treatment of candidiasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:662-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Etten, E. W. M., C. Van den Heuvel-de Groot, and I. A. J. M. Bakker-Woudenberg. 1993. Efficacies of amphotericin-B-desoxycholate liposomal amphotericin-B and fluconazole in the treatment of systemic candidosis in immunocompetent and leucopenic mice. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 32:723-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vincent, J. L., E. Anaissie, H. Bruining, W. Demajo, M. Elebiary, J. Haber, Y. Hiramatsu, G. Nitenberg, P. O. Nystrom, D. Pittet, T. Rogers, P. Sandven, G. Sganga, M. D. Schaller, and J. Solomkin. 1998. Epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment of systemic Candida infection in surgical patients under intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 24:206-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zarif, L., J. R. Graybill, D. Perlin, L. Najvar, R. Bocanegra, and R. J. Mannino. 2000. Antifungal activity of amphotericin B cochleates against Candida albicans infection in a mouse model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1463-1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]