Abstract

Background

Although patients with critical limb ischemia (CLI) commonly undergo major limb amputation, the quality of life (QOL) of this group remains poorly described. Therefore, we sought to describe which domains vascular amputees consider important in determining their health-related QOL.

Methods

We performed 4 focus groups in patients who had major lower extremity amputations resulting from CLI. They were conducted at 4 distinct centers across the United States to ensure broad geographic, socioeconomic, and ethnic representation.

Results

Of 26 patients (mean age, 64 years), 19 (73%) were Caucasian, 6 (23%) were African American, and 1 (4%) was Native American. Nearly, three-quarter of patients were men (n = 19, 73%) and had a high-school education or more (n = 19, 73%). Overall, 8 (31%) were double amputees and 17 (65%) had diabetes. Time since amputation varied across patients and ranged from 3 months to more than 27 years (mean, 4.3 years). Patients stated that their current QOL was determined by impaired mobility (65%), pain (60%), progression of disease in the remaining limb (55%), and depression/frustration (54%). Across 26 patients, more than half (n = 16, 62%) described multiple prior revascularization procedures. Although most felt that their physician did his/her best to salvage the affected leg (85%), a sizable minority would have preferred an amputation earlier in their CLI treatment course (27%). Furthermore, when asked how their care might have been improved, patients reported that facilitating peer support (88%), more extensive rehabilitation and prosthetist involvement (71%), earlier mention of amputation as a possible outcome (54%), and the early discontinuation of narcotics (54%) were potential areas of improvement.

Conclusions

Although QOL in vascular amputees seems primarily determined by mobility impairment, pain, and emotional perturbation, our focus groups identified that physician-controlled factors such as the timing of amputation, informed decision making, and postamputation support may also play an important role. The assessment of patient preferences regarding maintenance of mobility at the cost of increased pain versus relief of pain with amputation at a cost of diminished mobility is central to shared decision making in CLI treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Lower extremity amputation is a major morbid event, and its prevention has long been the foremost goal in critical limb ischemia (CLI) treatment, almost at all costs. Approximately, 1 million Americans suffer from CLI, and more than 150,000 new cases are diagnosed annually in the United States.1–3 Of these, about 20% will undergo major lower extremity amputation within 1 year of diagnosis, 4,5 whereas even higher amputation rates have been reported in certain high-risk patient subsets.6–10 Although the number of endovascular and surgical interventions for CLI has dramatically increased over the last decade, trends suggest that the number of amputations in CLI patients is only modestly declining if not remaining constant.11,12 Furthermore, amputation is greatly feared by patients,13 and the incidence of limb loss (or conversely–limb salvage) has been incorporated into society-endorsed outcome guidelines as an important measure of lower extremity revascularization quality and performance.14–16

However, recent reports suggest that in light of patient-centered outcomes such as functional status and quality of life (QOL), a certain subset of CLI patients may have equivalent results with a primary amputation as opposed to aggressive revascularization strategies.17,18 Although some have investigated a more focused measure of functional status and “mobility success,”19,20 a broad but disease-specific QOL measure for CLI patients is not available. Traditional QOL scores used in lower extremity peripheral vascular disease, such as the VascuQol and the PAVK-86, were derived and validated primarily in patients with claudication and may not be generalizable to patients with CLI.21–23 Furthermore, broad QOL tools, such as the SF-36, the EuroQoL EQ-5d, and the Nottingham Health Profile,24–26 are generic measures and are unable to adequately detect changes in emotion, mental health, or social functioning of patients with worsening limb ischemia.22,27 Therefore, a more precise way to describe QOL in patients with CLI and amputation needs to be defined.

To better understand what domains determine QOL in vascular amputees from CLI, we conducted focus groups with an ethnically, geographically, and socioeconomically diverse patient cohort. We hoped to gain better insight into how CLI patients at the far end of the disease spectrum define their health-related QOL and thus to learn how physicians might incorporate shared decision making with patients in the CLI treatment process.

METHODS

Patient Selection

To be considered for focus group participation, patients had to have undergone at least one major lower extremity amputation (above or below knee) because of either ischemic rest pain and/or ischemic tissue loss. We did not establish exclusive parameters around the length of time since amputation, the number of limb salvage attempts patients had before amputation, or current functional status. Eligible participants had to be able to read and speak fluently in English and be at least 18 years old. They could be of either sex and of any race, and we did not discriminate on the basis of educational background.

Focus group participants were recruited at 4 different institutions: University of Utah Hospital (U of U), Salt Lake City Veterans Administration Hospital (SLC VA), Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center (DHMC), and Emory University Hospital (Emory). Recruitment was performed via posted flyers or by personal invitation of eligible patients by staff in the cardiovascular, vascular surgery, and rehabilitation clinics at these institutions. The medical records of all eligible patients were reviewed to confirm the indication for amputation. A personal telephone invitation was then extended followed by a mailed letter explaining the details, risks, and benefits of the scheduled focus group session. The Institutional Review Board evaluated and approved this study at each institution.

Focus Groups

A total of 4 individual focus group sessions were scheduled and conducted with 1 group at each of the 4 participating institutions. Sessions were moderated by trained personnel from the Center for Survey Research (CSR) at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, or from the University of Utah Center for Clinical and Translational Science. Physicians and clinical personnel were intentionally excluded from focus group leadership during the sessions, to avoid bias in participant responses. To ensure that all groups were conducted in a uniform fashion, we developed and used a scripted moderator’s guide to pose open-ended questions that encompassed a broad spectrum of QOL domains, allowing participants to freely describe their opinions. An abbreviated version of the questions asked of the participants via the moderator’s guide is presented in Table I.

Table I.

Abbreviated moderator guide

| Section | Topic and questions | Time (min) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction

|

10 |

| 2 | Warm up

|

10 |

| 3 | Impact of amputation on daily function and quality of life

|

20 |

| 4 | Experiences with mobility aids and prostheses

|

15 |

| 5 | Emotional impact

|

10 |

| 6 | Concerns about having an amputation

|

20 |

| 7 | Attitudes about treatment course before amputation

|

15 |

| 8 | Anything else?

|

5 |

| 9 | Closing

|

5 |

This table shows a summative listing of the key categories investigated and questions that were asked by the focus group moderator. The guide was revised after each session with the final version depicted here. Moderators were ad liberty to expound and lead the group discussion as they felt, however, they had to include all these key questions.

The focus groups were conducted in a nonclinic environment. They were video and audio recorded for analysis and comparison. Sessions were closed to nonparticipants and lasted no more than 2 hr each. At the beginning of the focus groups, written informed consent was obtained from each participant, and for their time, they were each compensated $100 at the session’s conclusion.

Data Analysis

The focus group proceedings were audio and video recorded, and written transcripts of each session were created. Experts from CSR reviewed all sessions and provided a report with participant responses grouped by theme and ordered by frequency. A second team at the University of Utah consisting of a psychometrician, 2 epidemiologists, a statistician, and the primary investigative team reviewed the reports, videotapes, and transcripts for consistency and produced a similar analysis. We paid specific attention to the commonality of themes voiced by participants, agreement or disagreement within the groups, the frequency with which a topic was mentioned, and the length of time dedicated to it by patients. The patient was the final unit of analysis with each participant’s response receiving equal weight toward agreement or disagreement with the discussed topics. Participant responses were deidentified for analysis and were reported verbatim.

RESULTS

Focus Group Participants

We conducted 4 focus groups between January and December 2011. A total of 26 volunteer subjects participated in the groups, 7 each at U of U and SLC VA and 6 each at DHMC and Emory. Mean age of participants was 64 years with a range of 39–87 years. As provided in Table II, 19 (73%) patients were men, 19 (73%) were Caucasian, 6 (23%) were African American, and 1 (4%) was Native American. With regards to education, about one-quarter each completed some high school (27%), graduated high school (23%), completed some college (27%), or graduated college (19%). One (4%) had a postgraduate education.

Table II.

Patient demographics

| Number of participants | DHMC; n (%), N = 6 | SLC VA; n (%), N = 7 | U of U; n (%), N = 7 | Emory; n (%), N = 6 | Total; n (%), N = 26 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||

| Mean (range) | 64 (54–79) | 66 (53–81) | 59 (39–87) | 66 (56–72) | 64 (39–87) |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 5 (83) | 7 (100) | 3 (43) | 4 (67) | 19 (73) |

| Female | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 4 (57) | 2 (33) | 7 (27) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White | 6 (100) | 7 (100) | 6 (86) | 0 (0) | 19 (73) |

| African American | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (100) | 6 (23) |

| Native American | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) |

| Education | |||||

| Some high school | 3 (50) | 2 (29) | 1 (14) | 1 (17) | 7 (27) |

| High school graduate | 2 (33) | 0 (0) | 3 (43) | 1 (17) | 6 (23) |

| Some college | 0 (0) | 4 (57) | 0 (0) | 3 (50) | 7 (27) |

| College graduate | 1 (17) | 1 (14) | 2 (29) | 1 (17) | 5 (19) |

| Postgraduate | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) |

This table delineates the demographics of focus group participants.

Every attendee had at least 1 major (above or below knee) lower extremity amputation. Eight (31%) were bilateral amputees. Mean time since amputation for the cohort was 4.3 years with a range of 3 months to 27 years. A revascularization procedure, including surgical bypass or percutaneous endoluminal therapy, was performed in 21 (81%) patients before they underwent amputation. Sixteen (62%) underwent more than one revascularization procedure. Diabetes mellitus was a medical comorbidity in 17 (65%) participants.

Domains in QOL

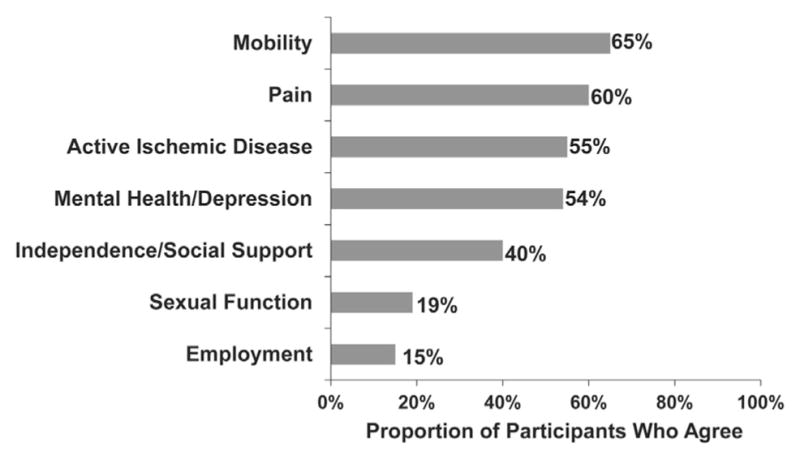

Once the analysis of the focus group data was complete, we found that several domains influence the health-related QOL of the attendant vascular amputees (Fig. 1). First, most participants (65%) felt that mobility, or the lack thereof, had the greatest impact on their QOL. They described their hardship with balance and outlined difficulties associated with walking up ramps or climbing stairs. Several attendees mentioned that limited mobility now precluded them from visiting certain venues, for example, their grandchildren’s house where the toys on the floor cause them to trip and fall. Example statements are listed in Table III.

Fig. 1.

Domains that determine quality of life in vascular amputees. This figure shows how many focus group participants felt each domain impacted their health-related quality of life.

Table III.

Representative patient quotations

| Domain | Selected statements of focus group participants |

|---|---|

| Mobility |

|

| Pain |

|

| Concern for remaining limb |

|

| Mental health/depression |

|

| Lack of independence & social support |

|

| Sexual function |

|

These are selected quotes from focus group participants. They are indicative of which domains influence quality of life in vascular amputees, as listed in the first column.

When asked about mobility aids, 68% of patients stated that they possess and try to use a prosthesis when able, whereas 83% stated that they nonetheless revert to using a wheelchair at least half the time. Regarding the impact of such mobility aids, focus group participants unanimously agreed that a prosthesis improves (or would improve) their QOL. Wheelchairs, however, were regarded as burdensome, difficult to maneuver, and generally used only when ambulation with a prosthesis or cane was not feasible.

Second, focus group participants reported that pain greatly influenced their QOL. As quoted in Table III, participants talked about how pain limited their daily activities, such as sleep, social interaction, and grocery shopping. Many commented on how limb pain was a key factor in the decision to amputate, yet how they were upset that it persisted beyond amputation in the form of phantom limb pain. Nonetheless, participants unanimously agreed that phantom limb pain was preferred over ischemic rest pain. In fact, phantom limb pain and/or sensation were experienced by 81% of patients; 46% were taking chronic narcotic medication, about half of which to deal with amputation-related pain and half for ongoing ischemic pain in the affected or contralateral limb. However, 54% of patients felt that it was important to quit using narcotic medication soon after the amputation.

A global concern for the remaining limb being threatened by ischemic disease was the third most commonly voiced domain, expressed by 55% of focus group participants. Those with a single amputation talked about how they would not be able to handle losing the contralateral limb (Table III). Double amputees who lost their legs in stages felt that 1 amputation was better than 2. Patients became protective of their residual limb and were more vigilant about seeking care for concerning ischemic symptoms. On questioning, 49% of participants stated that they currently suffered from either tissue loss and/or ischemic rest pain in their remaining leg (double amputees excluded).

Mental health concerns, specifically depression, impacted the QOL of 54% of participants. When asked, they described feeling alone and sad, often spending days without leaving their home. Further example statements are listed in Table III. A large part of their depression was traced to a lack of independence and social support, which 40% of patients felt limited their QOL. Many felt abandoned by their friends and family. We queried how many of the focus group participants had ever or currently participated in a support group and only 8% answered in the affirmative. However, when we asked if participants felt that a support group would improve their QOL, 88% agreed.

A minority (19%) of participants reported that sexual function was important to their QOL. Five subjects attributed a decline in their sexual activity and spousal relations directly to their limb loss (Table III). Four (15%) subjects had to change or discontinue their employment because of their limb loss. However, most patients (65%) were already unemployed at the time of amputation.

Critical Limb Ischemia Treatment Course

Participants were asked to comment on their respective treatment course for CLI. This included treatments and interventions on the leg before amputation and the decisions regarding timing and level of amputation. Our findings are summarized in Table IV. In retrospect, most participants were pleased with their treatment process. Most patients, 85%, felt that their physician did everything possible to try and save the affected leg. Several stated, “Most people would try anything to save the leg.” One participant said, “I definitely would have had the amputation at the same time point. My pain got so bad, I could not walk.” When asked, 85% of patients felt that intolerable ischemic rest pain is the most appropriate threshold for having their limb amputated, as opposed to ulceration, gangrene, or when their physician stated that limb salvage was no longer possible. One patient said, “If I could, I would have taken an axe and chopped off my leg sooner just to get rid of the pain.” As mentioned previously, all participant amputees preferred living with phantom limb pain as opposed to ischemic rest pain.

Table IV.

CLI treatment course

| Comments regarding CLI treatment course |

|---|

|

A summary of comments made by focus group participants regarding their CLI treatment course.

However, several of the patients had mixed feelings regarding their treatment course, stating things like “The more education we get and the sooner we get help, the better we can get back into society and on with life.” “Overall, I am not sure if I couldn’t have kept my leg longer.” In fact, 15% of patients said outright that they were displeased with their CLI treatment course. Their displeasure was due to different reasons. For one, 54% of participants felt that they were not madeaware of amputation as a possible outcome during their treatment course: “While I was told I had artery disease, I wasn’t told that I could lose my leg. I would have taken better care of myself.” On the other hand, some dissatisfaction stemmed from the timing of amputation; 27% of focus group participants wished they had received their amputation sooner in their treatment course. One patient stated, “I wish they had done the amputation three operations sooner,” whereas another said, “Just get on with it, let me heal and get back to life.” Finally, 71% of focus group participants wished that they had met their prosthetist sooner and had spent more time inrehabilitation. They advocated meeting with their prosthetist before the amputation, if possible, to become better informed of the goals and objectives of rehabilitation.

DISCUSSION

Revascularization and major amputation remain common treatment pathways for patients with CLI. Traditional outcome measures, such as limb salvage, patient survival, patency, and reintervention rates, have informed surgeons and aided in clinical decision making for these patients. However, many argue that what matters most to patients in the end is their resultant functional status and QOL.28,29 Thus, there has been a recent shift toward inclusion of patient-centered outcomes in research analyses performed in CLI cohorts, both in the United States30,31 and globally.32 The opinions expressed in the focus groups of vascular amputees highlight the importance of QOL in defining a “successful treatment outcome” for CLI. In our discussions, functionality and life quality remained the paramount topics raised by patients, not target lesion revascularization or residual stenosis. Specifically, we found that patients who had undergone treatment for CLI defined their QOL in terms of mobility, pain, ongoing ischemic disease and mental health. Therefore, these domains must be central to any measure used to assess QOL in patients who suffer from severe CLI and face possible amputation and arguably should be considered when choosing a treatment pathway.

Unfortunately, QOL in CLI patients has been difficult to measure. Although generic measures, such as the SF-36, the EuroQoL EQ-5d, and the Nottingham Health Profile, have been widely validated and found appeal because of their broad applicability and ease of interpretation, they lack discriminatory power in CLI patients. These patients tend to cluster at the very low end of QOL measurements given the multiple disease processes that coexist in them.23,27 The more disease-specific VascuQol instrument, 33 although accurate for patients with claudication, has poor differentiating power in CLI patients.23 Finally, no specific QOL measure for vascular amputees from CLI exists. When both the BASIL and PREVENT III cohorts were assessed for QOL with the VascuQol measure, the authors cited the inability to account for amputation-specific measures as a significant limitation.30,31

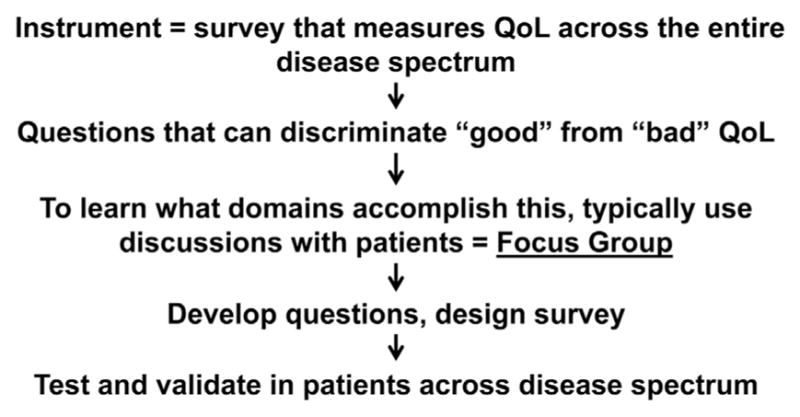

Given this need, how can the focus group results that we obtained help shape a more specific instrument? Figure 2 outlines, in an abbreviated fashion, the steps necessary for the creation of a good QOL instrument. In simple terms, it is crucial that such a survey can detect “bad” versus “good” QOL across the entire disease spectrum. To understand what domains are associated with “good” versus “bad,” discussions with representative patients are necessary and occur in the form of focus groups. From this qualitative data, pertinent questions are derived to increase the discriminatory capability and therefore the construct validity of the final survey. Because we are interested in the development of a shared decision tool for CLI, we conducted the focus groups described herein.

Fig. 2.

Development of a QOL instrument. A summary of the key steps in devising a QOL instrument.

Going into the focus groups, we expected that QOL in vascular amputees would likely be determined by similar measures as found in the generic instruments described previously, yet require refinement for discriminatory power. For example, we anticipated that mental health, physical symptoms, and social well-being would play a determinant role in our study population as these are key elements of most QOL measures. In general, these assumptions proved to be true. Yet, we were surprised to discover that some commonly measured psychometric domains, specifically sexual function and employment, factored very little into the QOL of vascular amputees. Therefore, these elements should probably be de-emphasized in a final disease-specific tool.

The focus groups further identified that mobility and pain not only are the two most important domains to affect QOL after amputation for CLI but also carry equal weight. These domains appear to conflict with one another. Maintenance of mobility favors a strategy of aggressive revascularization. Previous work has shown that mobility after lower extremity bypass is greatly improved by limb preservation and declines proportionally with higher levels of lower extremity amputation.34–36 Contrarily, we learned from the focus groups that relief for ischemic rest pain was accomplished by amputation, with more than a few patients wishing they had undergone amputation sooner instead of further attempts at revascularization. Therefore, the decision-making process between revascularization and amputation for the CLI patient with poor revascularization options should include a clear assessment of the relative importance of pain versus mobility to that patient.

Our findings indicate that a truly informative QOL assessment in CLI patients should seek to determine patient preferences regarding maintenance of mobility versus durable treatment of ischemic pain. This could be accomplished via a conjoint analysis or trade-off questions. For example, patients would be given scenarios of increasing ischemic pain versus improved mobility in incremental levels to assess at which threshold they would favor one over the other. In that manner, physicians may better understand individual patient values regarding these key elements and include them in the treatment decision-making process. This process would also improve the communication between surgeon and patient regarding possible treatment outcomes, an area which the focus group participants felt needed improvement.

We envision that a disease-specific QOL measure for CLI patients will facilitate the shared decision-making process between patient and physician regarding overall aggressiveness of revascularization versus timing of amputation. The survey will be designed for repeated administration at different times in the course of CLI treatment or natural history. Thus, the impact of interventions or progression of disease on QOL can be longitudinally assessed. With the inclusion of questions targeting trade-off valuation and patient preference, hopefully, the instrument will reliably add to existing anatomic and hemodynamic criteria to help identify those patients who would prefer and receive better outcomes with early amputation versus ongoing revascularization and attempts at limb salvage.

Our study has limitations. First, our qualitative data were obtained from patients who had undergone treatment for CLI and subsequently suffered major lower extremity amputation. Because patient preferences can change throughout the treatment course, the domains ascertained in this study may not directly apply to all patients while being actively treated for CLI. Therefore, our future work will encompass patients at varying stages of CLI presentation, treatment, and surveillance. This will allow us to generalize our findings to a broader CLI patient cohort. Second, our focus groups comprised a relatively small number of patients. However, we ensured that these patients were from broad ethnic, geographic, and educational backgrounds to give a representative sampling of our target population. Third, this study represents a first effort at focus group sessions targeting vascular amputees from CLI. For this reason, the groups were conducted in a highly specified manner, and they were led by an experienced team of survey researchers.

CONCLUSIONS

Although many patients with peripheral arterial disease suffer from CLI and undergo major leg amputation, the determinants of QOL in this patient subset remained poorly described. Our focus groups have identified that vascular amputees characterize their QOL primarily in terms of mobility, pain, ischemic symptoms, concern for limb loss, and mental health. Because limb salvage maintains mobility (perhaps at the expense of increased pain and suffering) while amputation appears to relieve ischemic pain (at the expense of mobility), the ability to accurately determine patient preferences in terms of pain and mobility appears to be crucial to shared decision making in CLI.

Acknowledgments

The work of B.D.S. has been supported by the Peripheral Vascular Surgery Society’s Academic Research Award, 2011.

The authors express their gratitude to the staff at the Center for Survey Research at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, for their help in conducting and analyzing the focus groups; the office staff of the Vascular Surgery Divisions at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City VA, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, and Emory University for their help in arranging and coordinating the focus groups; N. Joyce Linwood, RN, for her time and help in moderating the focus group at Emory University Hospital; Sandra Edwards, Charlene Weir, PhD, Man Hung, PhD, and Carol Sweeney, PhD, for their help with analytic review; and the Peripheral Vascular Surgery Society for supporting this research.

Footnotes

Presented at the Peripheral Vascular Surgery Society’s Spring Annual Meeting, June 2012, Washington, DC.

References

- 1.Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, et al. Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II) Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;33:S1–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Egorova NN, Guillerme S, Gelijns A, et al. An analysis of the outcomes of a decade of experience with lower extremity revascularization including limb salvage, lengths of stay, and safety. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:878–885. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.10.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peacock JM, Keo HH, Duval S, et al. The incidence and health economic burden of ischemic amputation in Minnesota, 2005–2008. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8:A141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolfe J, Wyatt M. Critical and subcritical ischaemia. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1997;13:578–82. doi: 10.1016/s1078-5884(97)80067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marston WA, Davies SW, Armstrong B, et al. Natural history of limbs with arterial insufficiency and chronic ulceration treated without revascularization. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:108–114. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowers B, Valentine R, Myers S, et al. The natural history of patients with claudication with toe pressures of 40 mm Hg or less. J Vasc Surg. 1993;18:506–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen LL, Hevelone N, Rogers SO, et al. Disparity in outcomes of surgical revascularization for limb salvage: race and gender are synergistic determinants of vein graft failure and limb loss. Circulation. 2009;119:123–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.810341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landry GJ. Functional outcome of critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:A141–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schanzer A, Mega J, Meadows J, et al. Risk stratification in critical limb ischemia: derivation and validation of a model to predict amputation-free survival using multicenter surgical outcomes data. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:1464–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.07.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Virkkunen J, Heikkinen M, Lepantalo M, et al. Diabetes as an independent risk factor for early postoperative complications in critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:761–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodney PP, Beck AW, Nagle J, et al. National trends in lower extremity bypass surgery, endovascular interventions, and major amputations. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sachs T, Pomposelli F, Hamdan A, et al. Trends in the national outcomes and costs for claudication and limb threatening ischemia: angioplasty vs bypass graft. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:1021–1031. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.03.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schoppen T, Boonstra A, Groothoff J, et al. Physical, mental and social predictors of functional outcome inunilateral lower-limb amputees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:803–11. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(02)04952-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conte MS, Bandyk DF, Clowes AW, et al. Results of PREVENT III: a multicenter, randomized trial of edifoligide for the prevention of vein graft failure in lower extremity bypass surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:742–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.12.058. discussion 51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conte MS. Understanding objective performance goals for critical limb ischemia trials. Semin Vasc Surg. 2010;23:129–37. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodney PP, Schanzer A, Demartino RR, et al. Validation of the Society for Vascular Surgery’s objective performance goals for critical limb ischemia in everyday vascular surgery practice. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:100–108. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.11.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sottiurai V, White JV. Extensive revascularization or primary amputation: which patients with critical limb ischemia should not be revascularized? Semin Vasc Surg. 2007;20:68–72. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nehler MR, Hiatt WR, Taylor LM. Is revascularization and limb salvage always the best treatment for critical limb ischemia? J Vasc Surg. 2003;37:704–8. doi: 10.1067/mva.2003.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norvell DC, Turner AP, Williams RM, et al. Defining successful mobility after lower extremity amputation for complications of peripheral vascular disease and diabetes. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:412–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor SM, Kalbaugh CA, Cass AL, et al. “Successful outcome” after below-knee amputation: an objective definition and influence of clinical variables. Am Surg. 2008;74:607–13. doi: 10.1177/000313480807400707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heidrich H, Bullinger M, Cachovan M, et al. Quality of life in peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Multicenter study of quality of life characteristics with a newly developed disease-specific questionnaire. Med Klin (Munich) 1995;90:693–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knipfer E, Reeps C, Dolezal C, et al. Assessment of generic and disease-specific health-related quality of life instruments in peripheral arterial disease. Vasa. 2008;37:99–115. doi: 10.1024/0301-1526.37.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Vries M, Ouwendijk R, Kessels AG, et al. Comparison of generic and disease-specific questionnaires for the assessment of quality of life in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:261–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247–63. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Busschbach JJ, McDonnell J, Essink-Bot ML, et al. Estimating parametric relationships between health description and health valuation with an application to the EuroQol EQ-5D. J Health Econ. 1999;18:551–71. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(99)00008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunt SM, McKenna SP, McEwen J, et al. A quantitative approach to perceived health status: a validation study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1980;34:281–6. doi: 10.1136/jech.34.4.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chetter IC, Scott DJ, Kester RC. An introduction to quality of life analysis: the new outcome measure in vascular surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1998;15:4–6. doi: 10.1016/s1078-5884(98)80065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abou-Zamzam AM, Lee RW, Moneta GL, et al. Functional outcome after infrainguinal bypass for limb salvage. J Vasc Surg. 1997;25:287–97. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(97)70350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gulati S, Coughlin PA, Hatfield J, et al. Quality of life in patients with lower limb ischemia; revised suggestions for analysis. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:122–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forbes JF, Adam DJ, Bell J, et al. Bypass versus Angioplasty in Severe Ischaemia of the Leg (BASIL) trial: Health-related quality of life outcomes, resource utilization, and cost-effectiveness analysis. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:43S–51S. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.01.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen LL, Moneta GL, Conte MS, et al. Prospective multicenter study of quality of life before and after lower extremity vein bypass in 1404 patients with critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:977–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.07.015. discussion 83–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar BN, Gambhir RP. Critical limb ischemia-need to look beyond limb salvage. Ann Vasc Surg. 2011;25:873–7. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2011.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morgan MB, Crayford T, Murrin B, et al. Developing the Vascular Quality of Life Questionnaire: a new disease-specific quality of life measure for use in lower limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33:679–87. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.112326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suckow BD, Goodney PP, Cambria RA, et al. Predicting functional status following amputation after lower extremity bypass. Ann Vasc Surg. 2012;26:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nehler MR, Coll JR, Hiatt WR, et al. Functional outcome in a contemporary series of lower extremity amputations. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:7–14. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taylor SM, Kalbaugh CA, Blackhurst DW, et al. Determinants of functional outcome after revascularization for critical limb ischemia: an analysis of 1000 consecutive vascular interventions. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:747–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.06.015. discussion 55–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]