Abstract

Genes homologous to enterococcal glycopeptide resistance genes vanA and vanB were found in glycopeptide-resistant Paenibacillus and Rhodococcus strains from soil. The putative d-Ala:d-Lac ligase genes in Paenibacillus thiaminolyticus PT-2B1 and Paenibacillus apiarius PA-B2B were closely related to vanA (92 and 87%) and flanked by genes homologous to vanH and vanX in vanA operons.

Glycopeptide resistance in enterococci is due to the replacement of the normal d-Ala-d-Ala termini in peptidoglycan cell wall precursors by low-affinity d-Ala-d-Lac or d-Ala-d-Ser termini (7). Three types of d-Ala:d-Lac ligases (VanA, VanB, and VanD) are associated with acquired resistance in enterococci (3), with VanA and VanB being the most prevalent. These proteins are distantly related to d-Ala:d-Lac ligases in lactic acid bacteria and to d-Ala:d-Ser ligases in VanC-type intrinsically resistant enterococcal species and in VanE- and VanG-type Enterococcus faecalis (1, 2, 11). Our present knowledge of the occurrence of vanA and vanB homologues in nonenterococcal bacteria is based on studies of single strains of Oerskovia turbata and Arcanobacterium haemolyticum (16), Streptococcus bovis (17), Bacillus circulans (9), Paenibacillus popilliae (15), and Eggerthella lenta and Clostridium innocuum (20). Glycopeptide producers Amycolatopsis orientalis (vancomycin) and Streptomyces toyocaensis (teicoplanin) have similar genes to avoid suicide (10, 14). However, it is unlikely that glycopeptide resistance was directly transferred from glycopeptide producers to enterococci, as inferred by the differences in sequence and G+C content of the resistance genes, as well as by the failure to reproduce such transfer under laboratory conditions (10, 14). More likely, other organisms acted as the sources of glycopeptide resistance genes in enterococci or as intermediates between glycopeptide producers and enterococci.

We have studied bacteria that were isolated from soil collected at three sites representing the most common landscape types in Denmark (6) and from previously described sites (18) (Table 1). Bacteria were isolated using media supplemented with vancomycin (10 μg/ml), cycloheximide (100 μg/ml) for fungal inhibition, and polymyxin B (5 μg/ml) for inhibition of gram-negative bacteria. For actinomycetes, 10 g of air-dried soil was mixed with 90 ml of peptone-buffered water, and 10-fold dilutions were plated on starch casein agar (22), followed by 5 days of incubation at room temperature. For isolation of endospore-producing organisms, cell extracts obtained by chemical soil dispersion (21) were heated at 80°C for 15 min and subcultured on brain heart infusion agar at 30°C for 3 days.

TABLE 1.

Glycopeptide-resistant strains isolated from soil

| Strain | Source of isolation

|

16s rDNA identification

|

MICa (μg/ml)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landscape | Soil use | Reference sp. | Accession no. | Identity (%) | VAN | TEC | |

| PT-2B2 | Unknown | Agriculture | Paenibacillus thiaminolyticusb | AB073197 | 100 | >32 | 4 |

| PA-B2B | Saale glaciation | Garden | Paenibacillus apiariusb | AB073201 | 99 | >32 | 4 |

| RG-S1F | Weichsel glaciation | Grassland | Rhodococcus globerulus | X81931 | 100 | >32 | 4 |

| RT-S5F | Weichsel glaciation | Grassland | Rhodococcus tukisamuensis | AB067734 | 97 | >32 | 8 |

| Rhodococcus koreensis | AF124343 | 97 | |||||

| RE-S7B | Saale glaciation | Garden | Rhodococcus equi | AF490539 | 98 | >32 | 8 |

| Rhodococcus opacus | X80630 | 97 | |||||

| RE-5A1 | Unknown | Agriculture | Rhodococcus erythropolis | AF501339 | 97 | >32 | 4 |

| Rhodococcus opacus | AB032565 | 96 | |||||

MICs of vancomycin (VAN) and teicoplanin (TEC) measured in Mueller-Hinton broth after 3 days of incubation at 30°C (Paenibacillus) or room temperature (Rhodococcus).

The hypervariable HV region (positions 70 to 344 according to B. subtilis numbering) was used as a marker for identification of Paenibacillus spp. as described by Goto et al. (4).

Glycopeptide-resistant isolates were tested by degenerate PCR for detection of vanA and vanB homologues using primers ddl-fwd (5′-TAI CCI GTI TTY GYK AAR CCB GC-3′) and ddl-rev (5′-GTI ARI CCS GGI ARI GTR TTG AC-3′). PCR mixtures were prepared using Ready-To-Go PCR beads (Pharmacia Amersham Biotech) and amplified under the following conditions: (i) an initial step at 95°C for 5 min; (ii) 35 cycles, with 1 cycle consisting of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 56°C, and 2 min at 72°C; and (iii) a final extension at 72°C for 10 min.

Of 11 isolates showing PCR products of the expected size (approximately 424 bp), six strains could be differentiated by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting using primers AB 106 (5′-TGCTCTGCCC-3′) and AB 111 (5′-GTAGACCCGT-3′). Two strains were identified as Paenibacillus apiarius (PA-B2B) and Paenibacillus thiaminolyticus (PT-2B1) by sequencing the hypervariable HV region of 16S rDNA (DNA coding for rRNA) (positions 70 to 344, Bacillus subtilis numbering) (4). Two reference strains of P. apiarius isolated in 1973 (NRRL B-4188) and 1975 (NRRL B-4299) were found to contain the same sequence (378 bp) of the PCR product obtained from strain PA-B2B, indicating that acquisition of this gene by P. apiarius was an ancient event that could have preceded the emergence of glycopeptide resistance in enterococci in the 1980s. The remaining four strains belonged to the genus Rhodococcus (Table 1).

The MICs of vancomycin and teicoplanin measured using commercial dehydrated panels (SensiTitre; Trek Diagnostics Systems, Cleveland, Ohio) after 3 days of incubation in Mueller-Hinton broth at 30°C (Paenibacillus) or room temperature (Rhodococcus) are reported in Table 1.

The complete sequences of the van-related genes in the two Paenibacillus strains were obtained after degenerate PCR amplification of the corresponding vanHAX clusters by long PCR using the Expand long template PCR system (Roche Diagnostics Corporation) with primers 1160 (5′-YATCGGCATTACYRTTTATGGATGTGAG-3′) and 1661 (5′-AAAATAGCTRYTGGGGTATGGTTCG-3′). P. apiarius PA-B2B and P. thiaminolyticus PT-2B1 harbored putative d-Ala:d-Lac ligase genes with high identity to vanA (87 and 92%, respectively) and lower identity to vanB (76% for both strains) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Percentages of identity between van-related genes in gram-positive bacteria

| Species | Identitya

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterococcus faecium B4147 (vanA) | Enterococcus faecalis V583 (vanB) | Paenibacillus apiarius PA-B2B | Paenibacillus thiaminolyticus PT-2B1 | Bacillus VR0709 | Paenibacillus popilliae ATCC 14706 | Amycolatopsis orientalis C329.2 | Rhodococcus globerulus RG-S1Fb | |

| Enterococcus faecium B4147 (vanA) | - | 76 | 87 | 92 | 93 | 77 | 58 | 58 |

| Enterococcus faecalis V583 (vanB) | 76 | - | 76 | 76 | 75 | 70 | 61 | 62 |

| Paenibacillus apiarius PA-B2B | 87 | 76 | - | 89 | 87 | 83 | 60 | 62 |

| Paenibacillus thiaminolyticus PT-2B1 | 92 | 76 | 89 | - | 92 | 78 | 59 | 59 |

| Bacillus circulans VR0709 | 93 | 75 | 87 | 92 | - | 77 | 58 | 62 |

| Paenibacillus popilliae ATCC 14706 | 77 | 70 | 83 | 78 | 77 | - | 58 | 59 |

| Amycolatopsis orientalis C329.2 | 58 | 61 | 60 | 59 | 58 | 58 | - | 76 |

| Rhodococcus globerulus RG-S1Fb | 58 | 62 | 59 | 62 | 62 | 59 | 76 | - |

The percentages of identity between van-related genes in comparisons of species. -, 100% identity (same species).

The percentages of identity for Rhodococcus globerulus RG-S1F are based on the partial sequence (378 bp) of the van-related gene in this strain.

The partial sequences of the vanH-like (930-bp) and vanX-like (606-bp) genes in strain PA-B2B were 79 and 84% identical to the corresponding genes in Tn1546. The partial sequences of the flanking genes in strain PT-2B1 were even more closely related to vanH (92% based on 930 bp sequenced) and vanX (94% based on 566 bp sequenced). These values are the highest degrees of identity to vanA, vanH, and vanX that have been reported for nonenterococcal strains of environmental origin. Patel et al. (15) reported a gene cluster homologous to vanHAX in the biopesticide Paenibacillus popilliae ATCC 14706, but the levels of identity to the corresponding enterococcal genes were only 75% to 80%. Higher levels of identity (91 to 95%) were reported for the clinical isolate B. circulans VR0709 (9).

The presence of genes closely related to vanA in Paenibacillus and Bacillus species suggests that members of these genera, and more generally gram-positive endospore-producing bacilli, could have played a role in the evolution or transfer of vanA-mediated glycopeptide resistance. The G+C contents of the genes in P. apiarius (48%) and P. thiaminolyticus (46%) were similar to that of vanA (45%) as well as to those of the genome of closely related species, such as B. subtilis (44%) but differed substantially from the G+C contents of enterococci (38 or 39%). These data suggest that (i) vanA probably originated from nonenterococcal species and (ii) the direction of gene transfer is likely to be from Bacillus spp. or from other genera with a similar G+C content to enterococci. Physical contact between members of the two bacterial populations is not unlikely in nature, since enterococci are widespread in the environment (7).

Lower levels of identity to both vanA (58%) and vanB (59 to 62%) were observed for the van-related genes in Rhodococcus strains based on the 378-bp sequences (Table 2). Similar identity levels to vanA and vanB have been reported previously for glycopeptide-producing actinomycetes (10). Although Rhodococcus spp. are actinomycetes, the putative d-Ala:d-Lac ligase gene sequences obtained from soil Rhodococcus isolates were quite different (76 to 77% identity) from those in glycopeptide producers. The same partial gene sequence was obtained from RT-S5F (most likely Rhodococcus tukisamuensis), RE-S7B (most likely Rhodococcus equi), and RE-5A1 (most likely Rhodococcus erythropolis). The sequence was 76% identical to that in Rhodococcus globerulus RG-S1F.

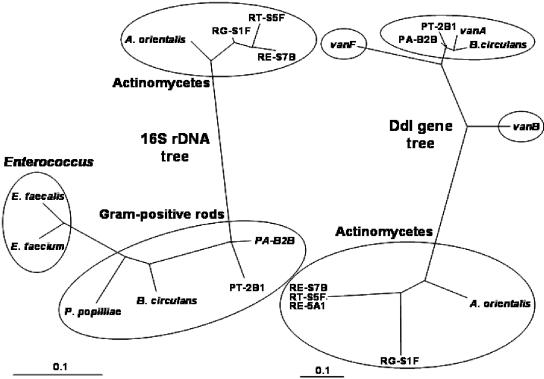

Phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood using fastDNAml (13) evidenced the close evolutionary relationship between vanA and the corresponding genes in P. apiarius, P. thiaminolyticus, and B. circulans. This was in contrast with the 16S rDNA divergence between these species and enterococci (Fig. 1). The topology of the two trees was congruent only with respect to the group of actinomycetes and to the two species P. apiarius and P. thiaminolyticus, which formed two monophyletic groups in both trees (Fig. 1). The difference in the natural logarithm of the likelihood between the two trees was significant on the basis of the test provided by fastDNAml. However, the ratio could be improved when vanA, vanB, and vanF (the van-related gene in P. popilliae) were manipulated to fit the 16S rDNA tree, providing an indication of the acquisition of these genes by horizontal gene transfer. The likelihood ratios of synonymous to nonsynonymous substitutions (ps/pn) calculated by SNAP (http://hcv.lanl.gov/content/hcv-db/SNAP/SNAP.html) without the Jukes-Cantor correction (8, 12, 19) indicated a positive Darwinian selection with a mean value of 3.4 and a tendency for higher ratios for vanB (4.6) and vanF (4.1). A positive rate is interpreted as purifying selection eliminating amino acid changes (19). Thus, it appears that Darwinian selection acted at a similar level on all van-related genes and only limited changes occurred in the sequences of these genes because of random mutations, especially in vanB and vanF. Significant recombination within van-related genes was not detected by PLATO (5).

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic trees based on sequences of 16S rDNA and van-related genes in gram-positive bacteria. PA-B2B was identified as P. apiarius, and PT-2B1 was identified as P. thiaminolyticus. RG-S1, RT-S5F, RE-S7B, and RE-5A1 belong to the genus Rhodococcus.

This study shows that genes nearly identical to those encoding glycopeptide resistance in human pathogens occur in soil bacterial communities. This finding opens new perspectives in the study of the origins of glycopeptide resistance as well as resistance to other antibiotics produced by soil organisms. As a result of long-term exposure to antibiotics produced in situ, soil bacteria have had the physiological need to counteract the activity of antibiotics long before the introduction of these substances in human medicine. Soil bacteria are therefore likely to be the first organisms, together with antibiotic producers, in which resistance developed. Accordingly, more information on the occurrence and diversity of antibiotic resistance genes in soil bacteria would enforce the current knowledge on evolution of antibiotic resistance and shed light on the possible evolutionary pathways by which resistance originated in human pathogenic bacteria.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences of the van-related genes were submitted to GenBank and assigned the following accession numbers: AY648698 (P. apiarius PA-B2B, complete sequence), AY648035 (P. thiaminolyticus PT-2B1, complete sequence), AY648697 (R. globerulus RG-S1F, partial sequence), and AY648036 (Rhodococcus sp. strain RE-S7B, partial sequence).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grant 23-01-0170 from the Danish Agricultural and Veterinary Research Council.

We thank M. H. Greve, A. Helweg, N. P. Petersen, and O. Edlefsen for making possible the collection of soil samples at the research stations of the Danish Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Y. Agersoe for providing soil samples, A. Rooney for providing reference strains of Rhodococcus spp., and P. Courvalin for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Evers, S., B. Casadewall, M. Charles, S. Dutka-Malen, M. Galimand, and P. Courvalin. 1996. Evolution of structure and substrate specificity in d-alanine:d-alanine ligases and related enzymes. J. Mol. Evol. 42:706-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fines, M., B. Perichon, P. Reynolds, D. F. Sahm, and P. Courvalin. 1999. VanE, a new type of acquired glycopeptide resistance in Enterococcus faecalis BM4405. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2161-2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gholizadeh, Y., and P. Courvalin. 2000. Acquired and intrinsic glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 16(Suppl. 1):S11-S17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goto, K., Y. Kato, M. Asahara, and A. Yokota. 2002. Evaluation of the hypervariable region in the 16S rDNA sequence as an index for rapid species identification in the genus Paenibacillus. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 48:281-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grassly, N. C., and E. C. Holmes. 1997. A likelihood method for the detection of selection and recombination using nucleotide sequences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 14:239-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greve, M. H., A. Helweg, M. Yli-Halla, O. M. Eklo, Å. A. Nyborg, E. Solbakken, I. Øborn, and J. Stenström. 1998. Nordic reference soils 537. Nordic Council of Ministers, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- 7.Guardabassi, L., and A. Dalsgaard. 2004. Occurrence, structure, and mobility of Tn1546-like elements in environmental isolates of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:984-990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korber, B. 2000. HIV signature and sequence variation analysis, p. 55-74. In A. G. Rodrigo and G. H. Learn (ed.), Computational analysis of HIV molecular sequences, vol. 4. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ligozzi, M., G. Lo Cascio, and R. Fontana. 1998. vanA gene cluster in a vancomycin-resistant clinical isolate of Bacillus circulans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2055-2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marshall, C. G., I. A. Lessard, I. Park, and G. D. Wright. 1998. Glycopeptide antibiotic resistance genes in glycopeptide-producing organisms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2215-2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKessar, S. J., A. M. Berry, J. M. Bell, J. D. Turnidge, and J. C. Paton. 2000. Genetic characterization of vanG, a novel vancomycin resistance locus of Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3224-3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nei, M., and T. Gojobori. 1986. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol. Biol. Evol. 3:418-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsen, G. J., H. Matsuda, R. Hagstrom, and R. Overbeek. 1994. fastDNAmL: a tool for construction of phylogenetic trees of DNA sequences using maximum likelihood. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 10:41-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel, R. 2000. Enterococcal-type glycopeptide resistance genes in non-enterococcal organisms. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 185:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel, R., K. Piper, F. R. Cockerill III, J. M. Steckelberg, and A. A. Yousten. 2000. The biopesticide Paenibacillus popilliae has a vancomycin resistance gene cluster homologous to the enterococcal VanA vancomycin resistance gene cluster. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:705-709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Power, E. G., Y. H. Abdulla, H. G. Talsania, W. Spice, S. Aathithan, and G. L. French. 1995. vanA genes in vancomycin-resistant clinical isolates of Oerskovia turbata and Arcanobacterium (Corynebacterium) haemolyticum. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 36:595-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poyart, C., C. Pierre, G. Quesne, B. Pron, P. Berche, and P. Trieu-Cuot. 1997. Emergence of vancomycin resistance in the genus Streptococcus: characterization of a vanB transferable determinant in Streptococcus bovis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:24-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sengelov, G., Y. Agerso, B. Halling-Sorensen, S. B. Baloda, J. S. Andersen, and L. B. Jensen. 2003. Bacterial antibiotic resistance levels in Danish farmland as a result of treatment with pig manure slurry. Environ. Int. 28:587-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith, N. H., J. Maynard Smith, and B. G. Spratt. 1995. Sequence evolution of the porB gene of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis: evidence of positive Darwinian selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 12:363-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stinear, T. P., D. C. Olden, P. D. Johnson, J. K. Davies, and M. L. Grayson. 2001. Enterococcal vanB resistance locus in anaerobic bacteria in human faeces. Lancet 357:855-856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wellington, E. M. H., P. Marsh, J. E. M. Watt, and J. Burden. 1997. Indirect approaches for studying soil microorganisms based on cell extraction and culturing, p. 311-329. In J. D. van Elsas, J. T. Trevors, and E. M. H. Wellington (ed.), Modern soil microbiology. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 22.Wellington, E. M. H., and I. K. Toth. 1994. Actinomycetes, p. 269-290. In R. W. Weaver (ed.), Methods of soil analysis. Part 2: Microbiological and biochemical properties. Soil Science Society of America, Inc., Madison, Wis.