Abstract

Mycobacterium avium causes disseminated infection in immunosuppressed individuals and lung infection in patients with chronic lung diseases. M. avium forms biofilm in the environment and possibly in human airways. Antibiotics with activity against the bacterium could inhibit biofilm formation. Clarithromycin inhibits biofilm formation but has no activity against established biofilm.

Mycobacterium avium is an environmental bacterium encountered in water and soil (11, 14). It is an opportunistic pathogen that has been associated with infection in birds, pigs, and humans, especially individuals with immunosuppression (11, 14).

As an environmental bacterium, it has been shown to form biofilm in water collections and in urban pipes (8, 12). In addition, M. avium has been isolated from sauna walls in Finland (20).

The ability of mycobacteria to form biofilm has been recently linked to the production of glycopeptidolipid (18). A number of identified genes have been associated with the impaired ability of M. avium to form biofilm (L. Bermudez, M. Wu, Y. Yamazaki, Y. Li, and L. S. Young, Abstr. 43rd Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. B-1039, 2003).

In humans, M. avium can cause disseminated disease in individuals with AIDS, as well as localized infection, as observed in patients with chronic lung diseases, such as emphysema, and in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis (1, 14, 23). More recently, M. avium lung infection in elderly women without any predisposing condition has been described, and these types of cases may be increasing (17).

The association of M. avium with chronic lung infection, a condition commonly resistant to treatment with antibiotics, has suggested the possibility that this bacterium could survive in the airways by assuming a phenotype associated with the formation of biofilm. Clinical experience shows that infection is frequently recurrent and that several cycles of antibiotic treatment are usually required to achieve cure. The protection from antibiotics of bacteria growing in biofilms has been previously described and probably depends on a combination of several factors (23). The most intuitive is that antibiotics fail to physically penetrate the biofilm.

Because of the potential clinical implications, we designed experiments in an attempt to obtain some information about the ability of clinically used anti-M. avium drugs to inhibit or prevent biofilm formation.

M. avium strains 101, 104, 109, and A5 were obtained from the blood of AIDS patients. The first three strains belong to serovars 1 (101 and 104) and 4 (109), while the serotype of A5 is unknown. Strain A5 was kindly provided by K. Eisenach (Little Rock, Ark.). Culture stocks were established following isolation, and bacteria used in the present study were obtained from the stock. Mycobacteria were grown in Middlebrook 7H10 aerobically at 37°C and an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Testing for susceptibility to azithromycin, clarithromycin, and moxifloxacin was carried out by the BACTEC microdilution method as previously described (15). Bacteria were used at late log phase. Approximately 105 bacteria were added to the medium with different concentrations of antibiotics. The compounds were gifts from Pfizer (Groton, Conn.), Abbott (Abbott Park, Ill.), and Bayer (West Haven, Conn.), respectively. The antibiotics were prepared according to instructions from the manufacturers. They were further diluted in balanced Hanks' salt solution (HBSS; Difco), as previously reported, to the desired concentration (15). In addition, bacteria retrieved from biofilms were also examined for antibiotic sensitivity. Briefly, well-developed biofilm colonies were removed from the polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plates (Falcon 3911, Microtest III flexible assay plate; Becton Dickinson, San Diego, Calif.) and resuspended in 5 ml of HBSS. The suspension was agitated by vortex for 2 min. The bacterial suspension was then processed as described above (2, 3). To create a dispersed suspension, bacteria were passed through a 23-gauge needle 10 times and placed in a 15-ml polystyrene tube. After 5 min of rest at room temperature, the top half of the suspension was obtained and an aliquot was stained with acid-fast stain for observation under the microscope.

Biofilm was prepared as previously described (9). Briefly, 107 bacteria in 200 μl of HBSS were seeded in a PVC covered plastic 96-well microfilter plate. The biofilm was assayed by determining the ability of cells to adhere to wells, as reported previously (9). Following inoculation, plates were incubated at room temperature for up to 14 days. To measure biofilm formation, supernatant was removed from the well and 25 μl of a 1% crystal violet solution (Sigma Co., St. Louis, Mo.) was added to each well (the dye stains bacterial cells but not the PVC material). The plates were incubated at room temperature for 15 min, rinsed vigorously four times with water, and blotted on paper. The crystal violet was dissolved in 95% ethanol, and the presence of dissolved biofilm was scored by measuring A570 with a spectophotometer, as previously described (9). Biofilm of M. avium 101 was also prepared for scanning electron microscopy as previously described (4).

To determine if azithromycin, clarithromycin, and moxifloxacin had any effect on M. avium biofilm, bacterial suspensions of 107 bacteria were seeded in the PVC plates and exposed to the antibiotics at a 50% subinhibitory concentration from day 0. Antibiotics were maintained in the wells for the duration of the experiments. Biofilm formation was scored at day 14. In some experiments, antibiotics were added at days 0, 2, 4, and 7 after seeding bacteria in order to determine if suppressive activity could be observed in the course of biofilm formation. Biofilms were then monitored for 14 days after the addition of antibiotics and then scored. Assays in which clarithromycin was added to established M. avium biofilms were also carried out. Briefly, established M. avium biofilms (14 days) were treated with clarithromycin at 50% of the MIC (1 μg/ml) or at the MIC (2 μg/ml) for an additional 14 days. Thereafter, the amount of biofilm on the PVC plate was determined and compared with biofilm not treated with clarithromycin.

Each experiment was repeated at least four times, and the results are expressed as the means ± standard deviations. The experimental results were compared with the controls and analyzed by the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

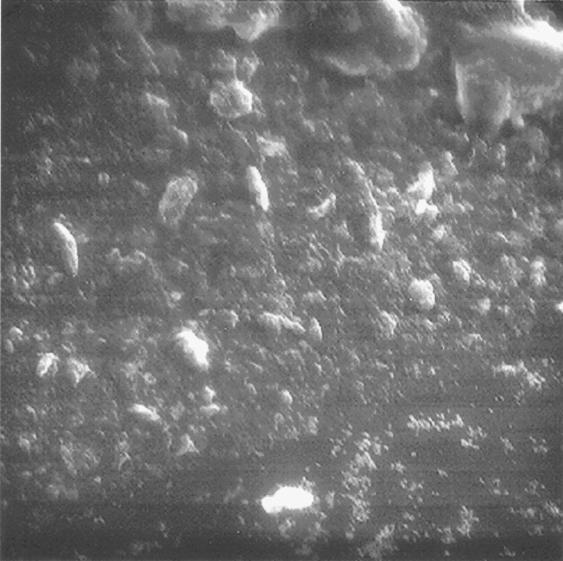

Figure 1 shows the biofilm formed by strain 101. The concentrations of azithromycin, clarithromycin, and moxifloxacin that were inhibitory to M. avium strains 101, 109, 104, and A5 were 16, 2, and 2 μg/ml, respectively. Because biofilm can select for antibiotic-resistant strains, established M. avium biofilms were dispersed and the strains were tested for susceptibility to antibiotics. The MICs for the biofilm bacteria were the same as those for the planktonic bacteria, demonstrating that bacteria obtained from biofilm maintain the same antibiotic susceptibility observed in planktonic bacteria.

FIG. 1.

Scanning electron micrograph of M. avium 101 biofilm. Bacteria were seeded on a PVC plate (108 bacteria) and allowed to establish biofilm for 14 days at room temperature. Then the wells were washed and dried, and the bottom of the PVC plate was cut with a blade. It was fixed and stained as described previously (4).

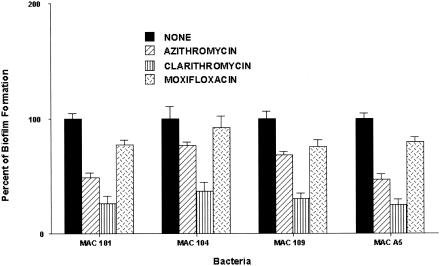

To determine if exposure to azithromycin, clarithromycin, and moxifloxacin, which have anti-M. avium activity, would inhibit biofilm formation, M. avium strains 101, 104, 109, and A5 (107 bacteria) were seeded on a PVC plate and simultaneously exposed to the above-cited antibiotics at 50% of the MICs (8, 1, and 1 μg/ml respectively). As shown in Fig. 2, clarithromycin, but not azithromycin or moxifloxacin, was associated with a significant decrease in the ability of M. avium to form biofilm over the period of the experiment. Exposure to clarithromycin led to an approximately 70% reduction in biofilm formation (P < 0.01) with all the tested strains. Azithromycin treatment resulted in approximately 40 and 45% reductions of the ability of M. avium 101 and A5, respectively, to form biofilms (P < 0.05), but it did not significantly impact the ability of strains 104 and 109 to establish biofilms.

FIG. 2.

Effect of azithromycin, clarithromycin, and moxifloxacin on the ability of M. avium to form biofilm. Bacteria were seeded onto a PVC plate and incubated with a subinhibitory concentration of azithromycin (8 μg/ml), clarithromycin (1 μg/ml), or moxifloxacin (1 μg/ml) for 14 days. Biofilm establishment was determined as described in the text. *, P < 0.05.

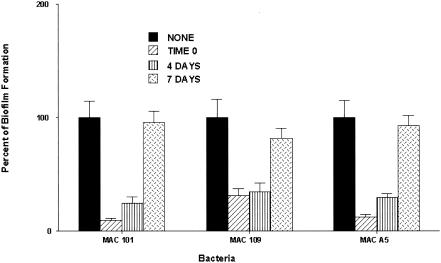

To investigate whether clarithromycin could inhibit biofilm formation if added after the seeding of bacteria on PVC plates, 107 bacteria were added to PVC wells and exposed to clarithromycin at 1 μg/ml at day 0, 4, or 7. The experiment was terminated after 14 days following exposure to the compound. Clarithromycin, when added at day 0 or 4 after bacterial seeding on PVC plates, significantly inhibited the formation of M. avium biofilm. For M. avium strain 101, the reduction was approximately 90% if the drug was added at day 0 and 76% if it was added at day 4. For strain 190, it inhibited 68% of biofilm if added at day 0 and 63% if added at day 4. Treatment at day 7 had no significant effect on the course of biofilm formation (Fig. 3). Both azithromycin and moxifloxacin had no effect on biofilm when added at day 4 or 7 after seeding (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Ability of clarithromycin to inhibit biofilm formation when added to M. avium at 0, 4, or 7 days after seeding, at a subinhibitory concentration. Biofilm establishment was determined as described in the text. *, P < 0.05.

To verify if established biofilm (14 days), when exposed to clarithromycin (1 or 2 μg/ml) for 14 days, shows any sign of regression, M. avium 101 on PVC plates was treated for 14 days with clarithromycin (1 or 2 μg/ml). After 2 weeks, the biofilm was measured as described above. The results show that the antibiotic has no impact (either at 50% of the MIC or at the MIC) on established bacterial biofilm. In some of the assays, the concentration of clarithromycin was replenished once or twice during the course of the experiment, without any effect on the biofilm. The activity of the drugs was measured by biological assay at the midway point and at the end of the experiment, with activity being detected.

In this work we showed that clarithromycin and, less efficiently, azithromycin but not moxifloxacin, three compounds with potent anti-M. avium activity, were able to inhibit the formation of M. avium biofilm on PVC. The effect of clarithromycin was observed at a subinhibitory concentration at which the bacterial growth is not inhibited. In addition, clarithromycin, added up to 4 days after M. avium seeding on PVC plates, was still able to significantly inhibit the formation of biofilm. In contrast, the antibiotic had no effect on established biofilm. One should consider, however, that at other concentrations azithromycin might be active.

One of the major problems for physicians dealing with patients with M. avium infection of the lung is the recurrence of the disease, even following therapy with an active antibiotic (21). The reason for therapy failure in this population is unknown but could be related to biofilm formation in the airways. M. avium has the ability to form biofilm in urban pipes and several surfaces (13). A number of studies have demonstrated that, in patients with bronchiectasis and in those with cystic fibrosis, the inefficiency of antibiotics used to treat the superimposed infection is related to the ability of the microorganisms to form biofilm (10, 19). In our study, bacteria recovered from established biofilm were still susceptible to azithromycin, clarithromycin, and moxifloxacin, despite the resistance of the biofilm to the action of the antibiotics.

Two explanations have long dominated the debate for the reduced antibiotic susceptibility that is observed in biofilms. The first and most intuitive is that the antibiotic fails to physically penetrate the biofilm. The second explanation is that nutrient limitation leads to slow growth or stationary-phase existence for many of the cells in a biofilm, reducing their antibiotic susceptibility (7). More recently, it has been shown that a third possibility exists. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms bind to antibiotics, inactivating them (16). Whether any component of the M. avium biofilm is associated with similar mechanisms is currently unknown. M. avium biofilm was resistant to the action of antibiotics once established, but the mechanisms of resistance are unknown. The third possibility is less likely than the other two to be the explanation, based on past observation that quinolones, but not macrolides, are able to kill nonreplicating M. avium (6). A recent study has suggested that oxygen limitation and low metabolic activity are responsible for the tolerance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm to ciprofloxacin and tobramycin (22).

The observation that macrolides are more efficient that quinolones in preventing M. avium biofilm is interesting. Additionally, our finding that clarithromycin was more effective than azithromycin in suppressing biofilm formation is quite intriguing. Clarithromycin has been shown to be more active than azithromycin against M. avium in mice on a weight basis and in short-term treatment, while azithromycin is superior in deep tissues, which could explain the superior activity of clarithromycin in biofilms (5). Alternately, clarithromycin could have more activity against stationary-phase organisms than azithromycin. However, there is no evidence that macrolides have activity against nonreplicating M. avium. Although the difference in susceptibility could be explained by the ability to penetrate biofilm, there is no current evidence to indicate that clarithromycin would penetrate M. avium biofilm with more efficiency than azithromycin.

Recently, we and others have identified mycobacterial genes associated with biofilm formation (18; L Bermudez et al., 43rd ICAAC). The selection of antibiotics that target those genes in M. avium, even at subinhibitory concentrations, may have clinical applications. Our results demonstrated that clarithromycin, if employed early, has the potential to have a significant impact on biofilm formation, which would potentially prevent the extension of the disease in the lung. Future work will attempt to confirm these findings in an animal model.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kristin Armstrong and Denny Weber for the preparation of the paper. We are also in debt to Martin Wu for the technical help.

This work was supported by a grant from Abbott Laboratories, and by grant AI-25140 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aksamit, T. R. 2002. Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease in patients with pre-existing lung disease. Clin. Chest Med. 23:643-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bermudez, L. E., C. B. Inderlied, P. Kolonoski, M. Petrofsky, P. Aralar, M. Wu, and L. S. Young. 2001. Activity of moxifloxacin by itself and in combination with ethambutol, rifabutin, and azithromycin in vitro and in vivo against Mycobacterium avium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:217-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bermudez, L. E., C. B. Inderlied, P. Kolonoski, M. Wu, P. Aralar, and L. S. Young. 2001. Telithromycin is active against Mycobacterium avium in mice despite lacking significant activity in standard in vitro and macrophage assays and is associated with low frequency of resistance during treatment. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2210-2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bermudez, L. E., A. Parker, and J. R. Goodman. 1997. Growth within macrophages increases the efficiency of Mycobacterium avium in invading other macrophages by a complement receptor-independent pathway. Infect. Immun. 65:1916-1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bermudez, L. E., M. Petrofsky, P. Kolonoski, and L. S. Young. 1998. Emergence of Mycobacterium avium populations resistant to macrolides during experimental chemotherapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:180-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bermudez, L. E., M. Wu, E. Miltner, and C. B. Inderlied. 1999. Isolation of two subpopulations of Mycobacterium avium within human macrophages. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 178:19-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, M., D. G. Allison, and P. Gilber. 1988. Resistance of bacterial biofilms to antibiotics: a growth rate related effect? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 22:777-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carson, L. A., N. J. Petersen, M. S. Favero, and S. M. Aguero. 1978. Growth characteristics of atypical mycobacteria in water and their comparative resistance to disinfectants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 36:839-846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter, G., M. Wu, D. C. Drummond, and L. E. Bermudez. 2003. Characterization of biofilm formation by clinical isolates of Mycobacterium avium. J. Med. Microbiol. 52:747-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ebert, D. L., and K. N. Olivier. 2002. Nontuberculous mycobacteria in cystic fibrosis. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 16:221-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falkinham, J. O., III. 1996. Epidemiology of infection by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 9:177-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falkinham, J. O., III, C. D. Norton, and M. W. LeChevallier. 2001. Factors influencing numbers of Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, and other mycobacteria in drinking water distribution systems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1225-1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haas, C. N., and M. M. Paller. 1983. The ecology of acid-fast organisms in water supply treatment and distribution system. J. Am. Water Work Assoc. 75:139-144. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inderlied, C. B., C. A. Kemper, and L. E. Bermudez. 1993. The Mycobacterium avium complex. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 6:266-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inderlied, C. B., L. S. Young, and J. K. Yamada. 1987. Determination of in vitro susceptibility of Mycobacterium avium complex isolates to antimycobacterial agents by various methods. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 31:1697-1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mah, T. F., B. Pitts, B. Pellock, G. C. Walker, P. S. Stewart, and G. A. O'Toole. 2003. A genetic basis for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm antibiotic resistance. Nature 426:306-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prince, D. S., D. D. Peterson, R. M. Steiner, J. E. Gottlieb, R. Scott, H. L. Israel, W. G. Figueroa, and J. E. Fish. 1989. Infection with Mycobacterium avium complex in patients without predisposing conditions. N. Engl. J. Med. 321:863-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Recht, J., A. Martinez, S. Torello, and R. Kolter. 2000. Genetic analysis of sliding motility in Mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Bacteriol. 182:4348-4351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenzweig, D. Y. 1979. Pulmonary mycobacterial infections due to Mycobacterium intracellulare-avium complex. Clinical features and course in 100 consecutive cases. Chest 75:115-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schulze-Robbecke, R. F. R. 1989. Mycobacteria in biofilms. Zentbl. Hyg Umweltmed. 188:385-390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wallace, R. J., Jr., B. A. Brown, D. E. Griffith, W. M. Girard, and D. T. Murphy. 1996. Clarithromycin regimens for pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex. The first 50 patients. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 153:1766-1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walters, M. C., III, F. Roe, A. Bugnicourt, M. J. Franklin, and P. S. Stewart. 2003. Contributions of antibiotic penetration, oxygen limitation, and low metabolic activity to tolerance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms to ciprofloxacin and tobramycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:317-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolinsky, E. 1979. Nontuberculous mycobacteria and associated diseases. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 119:107-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]