Abstract

Approximately 60% to 87% of patients with heart failure (HF) report sexual problems, and numbers as low as 31% of HF patients younger than 70 have normal sexual function. When compared with healthy elders, the amount of perceived sexual dysfunction might be similar (around 56%), but patients with HF are reporting more erectile dysfunction (ED) and also perceive that their HF symptoms (20%) or HF medication (10%) is the cause for their problems. The prevalence of ED is highly prevalent in men with cardiac disease and reported in up to 81% of cardiac patients, compared with 50% in the general older population. In total 25–76% of women with HF report sexual problems or concerns.

The physical effort related to sexual activity in cardiac patients can be compared to mild to moderate physical activity. The related energy expenditure of sexual activity falls in the range of three to five metabolic units (METs), which can be compared to the energy needed to climb three flights of stairs, general housework, or gardening.

Information about sexual activity is often overlooked by health care professionals treating HF patients. Advice and counselling about this subject are needed to decrease worries of patients and partners, avoid skipping medication because of fear for side effects, or prevent inappropriate use of potency enhancing drugs or herbs.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is known to have consequences for physical function affecting daily life of the patient and his/her partner. Patients with HF may report a decrease in sexual performance, a loss of sexual pleasure or satisfaction, a decrease of sexual interest, and a decrease in the frequency of sex.1, 2, 3, 4 For a lot of HF patients, sexual health is important, with 52% of the men and 38% of the women with HF reporting that sex was important and sexual health was impacting their quality of life.5, 6

Although not every patient with HF suffers from sexual problems and the relationship between the patient and the partner is not always affected,7 several patients and partners have questions and worries. They may have questions about when to resume sexual activity, about possible dangers and what to do in case symptoms occur. In the American Heart Association (AHA) scientific statement on sexual Activity and Cardiovascular Disease,8 sexual activity is described to be reasonable for patients with compensated and/or mild [New York Heart Association (NYHA) class I or II] HF (Class IIa; Level of Evidence B). Sexual activity is not advised for patients with decompensated or advanced HF (NYHA class III or IV) until their condition is stabilized and optimally managed (Class III; Level of Evidence C).

Although the majority of health care professionals feel a certain responsibility to discuss patients' sexual health, in practice, they seldom address sex with their patients, even during cardiac rehabilitation or in general practice.9, 10, 11

From the patient side, patients also experience barriers to discuss their worries or questions around sexual function. Some feel embarrassed to address the topic, others do not want to embarrass the health care providers, or others fear that their health care provider is not experienced enough to understand his/her problems.9, 11

Not discussing sexual concerns with patients might lead to unnecessary worries or sadness of patients. Some patients even might skip their medication because they fear for side effects of their cardiac medications. Some patients start using substances that might help increase their potency or sexual desire, without knowing the possible consequences such as interaction with cardiac medications, vasoactive or sympathomimetic effects, and elevating or reducing systemic blood pressure (BP).8

This short summary article addresses the prevalence of sexual problems in HF patients and factors that are related to sexual problems and provides some basic information on energy, risk, and treatment. This information might help health care providers to address sexual health in their consultation.

Prevalence of sexual problems in heart failure patients

Approximately 60% to 87% of patients with HF report sexual problems.8 These problems include a marked decrease in sexual interest and activity, and one quarter of patients with HF report that they have stopped sexual activity altogether.1, 12 Other studies have found that normal sexual activity was observed only in 31% of patients younger than 70.5 When HF patients (n = 438) were compared with healthy elders (n = 459), the self‐reported amount of sexual dysfunction was similar, at 59% and 56%.2 However, HF patients reported significantly more often ED (37% vs. 17%).2 Sexual problems include a lack of interest in or fear for having sex, orgasmic difficulties, or erectile dysfunction (ED) in men.

ED occurs also in the general population, with increasing prevalence with age. The prevalence is estimated to be 50% in 60‐year‐old men.13, 14 But ED is reported in up to 81% of cardiac patients14 across different cultures and ethnic groups.15 Although in most studies more male patients report sexual problems, also women with cardiac disease are known to have more frequent sexual problems compared with women in the general population.16, 17 Women may experience other types of sexual dysfunction than men, including decline in sexual interest or desire, decline in sexual arousal, orgasmic disorder, or painful sexual intercourse.17 In a general population, 27% of women (age 50–59) reported lack of interest in sexual activity, and 23% of women were not able to have an orgasm.18 In a HF population, 80% of the female HF patients reported reduced lubrication and 76% reported frequent unsuccessful intercourse.16

Some sexual problems already are present prior to the onset of HF, but such problems also can develop during different phases in the HF trajectory.6 In a previous study, 27% of the patients without sexual problems at 1 month after discharge developed sexual problems over time. In 70% of the patients who had difficulties at 1 month after discharge, the sexual problems remained. At the same time, 30% of the patients, who reported sexual problems at 1 month after discharge, did not report difficulties in sexual activity at follow‐up.6

Factors related to sexual problems in heart failure patients

Most patients attribute their sexual problems to their HF symptoms; they perceived that shortness of breath (20%), fatigue (20%), medication use (10%), and limited circulation (11%) are causing their sexual problems.2

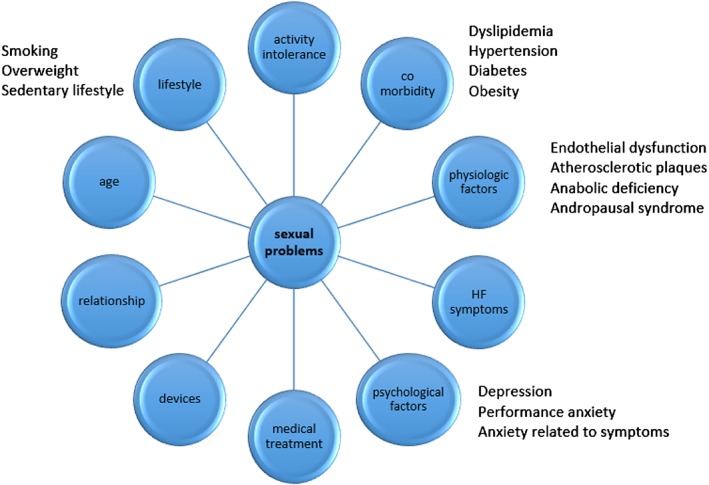

However, the mechanism behind sexual problems is complex. Sexual problems can be related to various demographic, clinical, and treatment factors5 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Factors related to sexual problems in heart failure patients.

HF specific factors that are related to sexual problems are HF symptoms such as dyspnea, fatigue, and activity intolerance. In addition, HF patients often suffer from comorbidity; up to 35% of HF patients suffers from COPD,19 and the overall prevalence of diabetes in HF is 20–25%.20 These comorbid conditions are known to be closely related to sexual problems.5 There is an over threefold increased risk of ED in diabetic vs. nondiabetic men,21 and diabetic women are more likely to report problems with lubrication (OR[95%CI] = 2.37[1.35–4.16]) and orgasm (OR[95%CI] = 1.80[1.01–3.20]) than nondiabetic women.22

Medication and device therapy

HF medications are often perceived to cause problems with sexual performance or libido, although newer generations of drugs appear to have fewer sexual side‐effects. On top of HF medication, other medication is prescribed for co‐morbid or underlying conditions, which might be the underlying reason for sexual problems.

In particular, thiazide diuretics may impact erectile function.23 Thiazide diuretics can cause endothelial dysfunction and increased vascular oxidative stress, as well as hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, a new onset of diabetes mellitus, and stimulation of the sympathetic system and the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system. Digoxin and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist are also described to have an effect on sexual performance or libido.23 Furthermore, the use of beta blockers can reduce sexual function;8, 23 however, data on third generation beta blockers currently used for HF treatment are inconsistent.23 HF patients have even reported an improvement of sexual performance with beta blockers, which is likely to be a result of both a reduction of HF severity and the ancillary properties of some of the third generation beta blockers.17 In addition, a nocebo effect, in which a patient's knowledge that a drug has been associated with ED, is often at least as important a contributing factor to a patient's ED as any physiological effect, particularly with contemporary blockers.8 In patients who develop sexual problems as a result of medication therapy, it can be helpful to switch to another drug from the same class or find a reasonable alternate strategy.8

Sexual problems can be related to other HF treatment such as device therapy or heart transplantation.24, 25 In a small study of 31 patients, 29% left ventricular assist device (LVAD) patients and 71% heart transplant patients reported being content with sexual activity; however, satisfaction with sex life was lower in transplant patients compared with HTx patients (7.6 ± 3.1 for HTx on a visual analogue scale vs. 3.9 ± 4.0 for LVAD patients, P = 0.017).24

In addition to HF symptoms, comorbidity, and HF treatment, several other factors such as psychological factors (depression, anxiety) can contribute to sexual problems.5 More general factors that are related to sexual function might be relevant to consider in the HF population as well, such as age, lifestyle, or problems in a relationship.5, 26

Energy consumption and risk related to sexual activity

Most studies on the actual energy consumption of sexual activity is performed in healthy young couples or normotensive men.27, 28 The energy required for sexual activity depends on its intensity and a person's physical condition. In the AHA statement, the physical effort related to sexual activity in cardiac patients is described to be considered as mild to moderate physical activity and the related energy expenditure in the range of three to five metabolic units (METs).8 The amount of energy needed for sexual activity is often compared with the energy needed to climb three flights of stairs, general housework, or gardening. At the same time, it was found that patients with HF had a VO2 < 10 mL/kg/min (i.e. 2.8 MET) and had an impaired sexual function.5

BP and heart rate (HR) can increase mildly during foreplay, with increases occurring transiently during sexual arousal and the greatest increases occur during the 10 to 15 s of orgasm, and a quick return to baseline BP and HR.8, 27 In HF patients, it was also found that they had an increased HR, right ventricular pressure, and diastolic pulmonary pressure during sexual activity (especially during orgasm).29

There is not a lot of data on the risk for exacerbation in patients' HF as a result of sexual activity. For patients deemed to be at high risk, sexual activity should be deferred until their condition is optimally managed and stabilized.8 Although some patients approach their physical limit during sexual activity, patients might still be able to have sex by their partner actively ensuring that they practice passive sex or sex helped by drugs or implants.

Counselling and treatment for sexual problems in heart failure patients

Some patients with HF might need specific information about activities they can undertake, as well as clear information and treatment to help cope with sexual problems.30 Because sexual problems might occur during the disease trajectory, sexual concerns need to be discussed more than once during treatment and should become an integral part of HF management and patient education. First, HF to be optimally managed and patient's condition should be stabilized before they resume sex.8 Furthermore, there are several practical advices that can help patients to optimally enjoy their sex life and intimacy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Issues to consider when advising heart failure patients on sexual activity

| General issues |

| • Choose appropriate setting |

| • Consider that sexual concerns are normal |

| • Discuss sexual activity for example within the context of exercise, during uptitration or initiation of medication |

| • Adapt terminology to the patients and partner |

| Assessment |

| • Use open‐ended questions |

| Examples: |

| General |

| ○ Many people with heart failure (or with symptoms like you have) have concerns about resuming sex. What concerns do you have? |

| ○ Some people report sexual problems as a result of prescribing medication. How is this for you? |

| More specific |

| ○ Have you noticed any changes in your sexual performance such as problems with erections or orgasm, vaginal dryness, or decreased desire for sex? If so, how often has this occurred? |

| • Consider using questionnaires such as Multidimensional Sexual Self‐concept Inventory (MSSI) or International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) for men or International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) for women |

| • Assess more than once if needed during the HF trajectory |

| Consider the right level of information and support needed |

| ○ Permission |

| ○ Limited information |

| ○ Specific suggestion |

| ○ Intensive therapy |

| Referral |

| • Refer to special trained counsellor, urologist, sexual therapist if needed |

| • Refer to cardiac rehab |

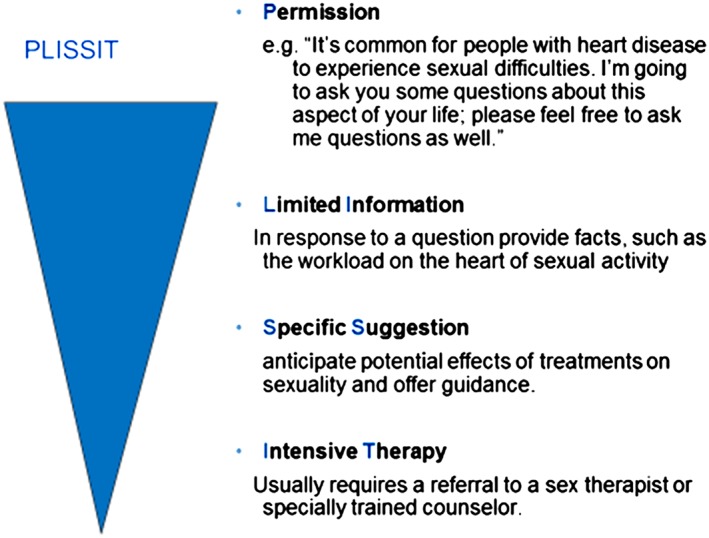

This information needs to be adapted to the personal situation of patients, sexual preferences, and culture.30, 31 One of the approaches that can be used to guide health professionals in determining needs of patients and in providing information related to sexuality is the so‐called PLISSIT model32 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The PLISSIT model to guide education and counselling.32

The basic idea of this approach is that all patients with HF should be given the opportunity to talk about sexual health in a more general way by informing them that this is an issue that patients might worry about and that they are welcome to discuss this with the health care provider. Some patients might need more information (Limited Information) that explains some basic facts and general information. From those, some patients might wish more detailed and specific information (Specific Suggestion), and even a smaller group might be in need of referral to specialist (Intensive Therapy) (Figure 2). Some patients might wish to be treated in case of ED. Phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE‐5) inhibitors are generally safe and effective for the treatment of ED in patients with systemic arterial hypertension, stable coronary artery disease, and compensated HF.8 However, PDE‐5 inhibitors should be used with caution in cases of intermediate cardiac risk and should be avoided in patients with high cardiac risk or patients who are concurrently being treated with nitrates.8

Concluding remarks

Sexual problems are common in men and women with HF and should be addressed to avoid possible fears and worries, to proactively prevent problems such as medication nonadherence or using medications or herbs that might endanger the health, and to prevent problems in the relationship between patient and partner.

Jaarsma, T. (2017) Sexual function of patients with heart failure: facts and numbers. ESC Heart Failure, 4: 3–7. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12108.

References

- 1. Westlake C, Dracup K, Walden JA, Fonarow G. Sexuality of patients with advanced heart failure and their spouses or partners. J Heart Lung Transplant 1999; 18: 1133–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hoekstra T, Lesman‐Leegte I, Luttik ML, Sanderman R, Veldhuisen van DJ, Jaarsma T. Sexual problems in elderly male and female patients with heart failure. Heart 2012; 98: 1647–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Driel AG, de Hosson MJ, Gamel C. Sexuality of patients with chronic heart failure and their spouses and the need for information regarding sexuality. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2014; 13: 227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alberti L, Torlasco C, Lauretta L, Loffi M, Maranta F, Salonia A, Margonato A, Montorsi F, Fragasso G. Erectile dysfunction in heart failure patients: a critical reappraisal. Androl 2013; 1: 177–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Apostolo A, Vignati C, Brusoni D, Cattadori G, Contini M, Veglia F, Magrì D, Palermo P, Tedesco C, Doria E, Fiorentini C, Montorsi P, Agostoni P. Erectile dysfunction in heart failure: correlation with severity, exercise performance, comorbidities, and heart failure treatment. J Sex Med 2009; 6: 2795–2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hoekstra T, Jaarsma T, Sanderman R, van Veldhuisen DJ, Lesman‐Leegte I. Perceived sexual difficulties and associated factors in patients with heart failure. Am Heart J 2012; 163: 246–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dalteg T, Benzein E, Fridlund B, Malm D. Cardiac disease and its consequences on the partner relationship: a systematic review. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2011; 10: 140–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Levine GN, Steinke EE, Bakaeen FG, Bozkurt B, Cheitlin MD, Conti JB, Foster E, Jaarsma T, Kloner RA, Lange RA, Lindau ST, Maron BJ, Moser DK, Ohman EM, Seftel AD, Stewart WJ. American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Sexual activity and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012; 125: 1058–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Byrne M, Doherty S, Murphy AW, McGee HM, Jaarsma T. Communicating about sexual concerns within cardiac health services: do service providers and service users agree? Patient Educ Couns 2013; 92: 398–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hoekstra T, Lesman‐Leegte I, Couperus MF, Sanderman R, Jaarsma T. What keeps nurses from the sexual counseling of patients with heart failure? Heart Lung 2012; 41: 492–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kolbe N, Kugler C, Schnepp W, Jaarsma T. Sexual counseling in patients with heart failure: a silent phenomenon: results from a convergent parallel mixed method study. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2016; 31: 53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jaarsma T. Sexual problems in heart failure patients. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2002; 1: 61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kostis JB, Jackson G, Rosen R, Barrett‐Connor E, Billups K, Burnett AL, Carson C 3rd, Cheitlin M, Debusk R, Fonseca V, Ganz P, Goldstein I, Guay A, Hatzichristou D, Hollander JE, Hutter A, Katz S, Kloner RA, Mittleman M, Montorsi F, Montorsi P, Nehra A, Sadovsky R, Shabsigh R. Sexual dysfunction and cardiac risk (the Second Princeton Consensus Conference). Am J Cardiol 2005; 96: 313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schwarz ER, Rastogi S, Kapur V, Sulemanjee N, Rodriguez JJ. Erectile dysfunction in heart failure patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 48: 1111–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hebert K, Lopez B, Castellanos J, Palacio A, Tamariz L, Arcement LM. The prevalence of erectile dysfunction in heart failure patients by race and ethnicity. Int J Impot Res 2008; 20: 507–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Steinke EE. Sexual dysfunction in women with cardiovascular disease: what do we know? Cardiovasc Nurs 2010; 25: 151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schwarz ER, Kapur V, Bionat S, Rastogi S, Gupta R, Rosanio S. The prevalence and clinical relevance of sexual dysfunction in women and men with chronic heart failure. Int J Impot Res 2008; 20: 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RG. Sexual dysfunction in the United States. JAMA 1999; 281: 537–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lainscak M, Anker S. Heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and asthma: numbers, facts, and challenges. ESC Heart Fail 2015; 2: 103–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Baliga V, Sapsford R. Diabetes mellitus and heart failure—an overview of epidemiology and management. Diab Vasc Dis Res 2009; 6: 164–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Feldman HA, Goldstein I, Hatzichristou DG, Krane RJ, McKinlay JB. Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: results of the Massachusetts Male Ageing Study. J Urol 1994; 151: 54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Copeland KL, Brown JS, Creasman JM, Van Den Eeden SK, Subak LL, Thom DH, Ferrara A, Huang AJ. Diabetes mellitus and sexual function in middle‐aged and older women. Obstet Gynecol 2012; 120(2 Pt 1): 331–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Baumhakel M, Schlimmer N, Kratz M, Hackett G, Jackson G, Böhm M. Cardiovascular risk, drugs and erectile function—a systematic analysis. Int J Clin Pract 2011; 65: 289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hasin T, Jaarsma T, Murninkas D, Setareh‐Shenas S, Yaari V, Bar‐Yosef S, Medalion B, Gerber Y, Ben‐Gal T. Sexual function in patients supported with left ventricular assist device and with heart transplant. ESC Heart Fail 2014; 1: 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vural A, Agacdiken A, Celikyurt U, Culha M, Kahraman G, Kozdag G, Ural D. Effect of cardiac resynchronization therapy on libido and erectile dysfunction. Clin Cardiol 2011; 34: 437–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hamilton LD, Julian AM. The relationship between daily hassles and sexual function in men and women. J Sex Marital Ther 2014; 2014: 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bohlen JG, Held JP, Sanderson MO, Patterson RP. Heart rate, rate‐pressure product, and oxygen uptake during four sexual activities. Arch Intern Med 1984; 144: 1745–1748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Littler WA, Honour AJ, Sleight P. Direct arterial pressure, heart rate and electrocardiogram during human coitus. J Reprod Fertil 1974; 40: 321–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cremers B, Kjellstrom B, Sudkamp M, Bohm M. Hemodynamic monitoring during sexual intercourse and physical exercise in a patient with chronic heart failure and pulmonary hypertension. Am J Med 2002; 112: 428–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Steinke EE, Jaarsma T, Barnason SA, Byrne M, Doherty S, Dougherty CM, Fridlund B, Kautz DD, Mårtensson J, Mosack V, Moser DK. Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing of the American Heart Association and the ESC Council on Cardiovascular Nursing and Allied Professions (CCNAP). Sexual counselling for individuals with cardiovascular disease and their partners: a consensus document from the American Heart Association and the ESC Council on Cardiovascular Nursing and Allied Professions (CCNAP). Eur Heart J 2013; 34: 3217–3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Akhu‐Zaheya LM, Masadeh AB. Sexual information needs of Arab‐Muslim patients with cardiac problems. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2015; 14: 478–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Annon, JS . The Behavioural Treatment of Sexual Problems. Volume 1: Brief Therapy. New York: Harper & Row; 1976. [Google Scholar]