Abstract

Background

Human Adenovirus (HAdV), especially species C (HAdV-C), can be detected incidentally by PCR in nasopharyngeal (NP) samples, making it difficult to interpret clinical significance of a positive result. We classified patients into groups based on HAdV culture positivity from respiratory specimens, and the presence of an identified co-pathogen. We hypothesized that HAdV-C would be over-represented and viral burden would be lower in patients most likely to have incidental detection (i.e, with a negative viral culture and documented co-pathogen).

Methods

Immunocompetent children with HAdV+ NP specimens were classified into 4 Groups: Group I (HAdV culture (+) and no co-infection), Group II (culture (+) and co-infection), Group III (culture (−) and no co-infection), and Group IV (culture (−) and co-infection). Viral burden (Ct) and species were compared among Groups.

Results

Of 483 NP specimens, HAdV was isolated in culture in 252 (52%); co-infection was found in 265 (55%) patients. Group I (most consistent with acute disease) had significantly lower Cts (median 23.9 [IQR 22.2–28.1]) compared with Group IV (most consistent with incidental detection, median 37.3 [IQR 35.3–38.9], p <0.0001). HAdV-C accounted for 41% samples of Group I and 83% of Group IV (p <0.0001). We identified a subset of 22 patients with bacterial or fungal co-pathogens, 18 of whom had no growth on viral culture (Group IV) with a median Ct of 37.4 (IQR 33.9–39.2).

Conclusions

Species identification and viral burden may assist in interpretation of a positive HAdV result. Low viral burden with HAdV-C may be consistent with incidental detection.

Keywords: Adenovirus, PCR, viral burden, Ct, adenovirus species, pediatrics, viral co-infection, bacterial co-infection

Introduction

Human adenoviruses (HAdV) account for 7–8% of viral respiratory illnesses in children less than 5 years1–3. HAdV infections can cause prolonged fever with elevated inflammatory markers4 and may mimic other illnesses that require specific treatment, such as bacterial infections or Kawasaki disease (KD)3–6. Over 60 HAdV types have been defined based on genomic sequences and are classified into 7 species (A–G). HAdV-C is known for its ability to establish persistence in lymphoid organs such as tonsils and adenoids7–9.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has become the standard diagnostic method for HAdV detection. It provides timely results with superior sensitivity to conventional methods. However, several aspects of molecular detection of HAdV make interpretation of a positive result from a nasopharyngeal (NP) specimen challenging. First, HAdV can be detected by PCR in the NP of up to 11% of healthy, asymptomatic children10–13, compared with the lower detection rate (0.6%) by culture3. Second, prolonged intermittent PCR detection of the same HAdV strain from NP secretions after primary infection has been described14. Third, a clinically relevant PCR for positivity has yet to be established15. Misattribution of the etiology of disease based on molecular detection of HAdV in respiratory specimens5, 12, 16 may have clinical consequences (e.g., coronary aneurysm because of delayed treatment for KD; or lack of treatment for serious bacterial infections in febrile infants). Accurate diagnosis of acute HAdV-associated disease is also crucial for evaluation of new antiviral treatments.

Because there is no practical gold standard for assessing whether the detection of HAdV in respiratory specimens using PCR is causal or incidental, we classified patients into 4 groups to assess for likelihood of HAdV causality of disease based on: 1) the ability to recover infectious HAdV in culture from their respiratory specimens, and 2) the presence of a simultaneously identified co-pathogen (viral, bacterial, or fungal) which may explain their clinical symptoms alternatively. Patients with sole HAdV detection and positive HAdV culture were considered most likely to have acute HAdV disease, while those with other co-pathogens and negative HAdV culture were considered least likely to have acute HAdV disease. We hypothesized that in cases most consistent with incidental detection, specimens would have a lower viral burden, and a higher percentage of HAdV-C.

Methods

Study population: symptomatic patients

Patients <21 years with a HAdV PCR+ respiratory specimen from 8/2011–12/2012 were identified from laboratory records. Patients were tested using the standard respiratory viral PCR panel (RVP) per clinician request at urgent care centers/emergency department or inpatient units. Subjects with underlying medical conditions were included, but those with immunodeficiency or receiving immunosuppressive medications were excluded. Only the first HAdV+ respiratory specimen from an individual patient was included. The study was approved by the Nationwide Children’s Hospital (NCH) Institutional Review Board.

Study population: asymptomatic, healthy children

Forty-eight NP swabs specimens from healthy children who were asymptomatic at least 2 weeks prior to enrollment were prospectively collected and tested for the standard RVP panel with IRB approval from (collected from 8/2010 to 1/2012) for respiratory viral testing (see below).

Clinical Laboratory PCR Testing

The RVP consists of separate laboratory-developed tests for detection of HAdV, human metapneumovirus (hMPV), parainfluenza viruses 1, 2 and 3 (PIV) and human rhinovirus/enterovirus (HRV/EV) using a real-time PCR format based on previous studies with slight modifications17, 18, 19. The Hologic ProFlu+ assay identified influenza A/B and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Total nucleic acid was extracted from 200 μL of sample using the NucliSENS EasyMag (bioMerieux, Burlington, NC), and eluted into 110 μL for analysis as above. Remnant specimens were stored at −80°C for further testing. The semi-quantitative HAdV real-time PCR was based the protocol developed by Heim et al.5, 20 targeting a conserved region of the HAdV hexon gene and designed to detect all serotypes of HAdV. Samples were considered HAdV positive if threshold cycles (Ct, inversely correlated with viral burden) were ≤40.

HAdV Culture Isolation

At Lovelace Respiratory Research Institute (LRRI), clinical specimens were inoculated onto A549 cell monolayers for HAdV isolation21–23. Samples had undergone only one freeze-thaw cycle before inoculation to cell cultures.

HAdV Species Identification

For all specimens, direct molecular species identification (DMS) from the original respiratory specimen was performed at NCH (Fig.1B). Primer/probe sets that detect HAdV-A, C and D were described previously with modification24; primer/probe sets that detect HAdV-B, E and F were designed on the basis of the available HAdV DNA sequence information (NCBI database) (Supplemental Table 1). In addition, if HAdV was isolated in culture, species (and type) identification was performed at LRRI by restriction enzyme analysis of viral genomic DNA and by amplification and sequencing of hexon and fiber genes as previously described (Fig. 1B)5, 21–23.

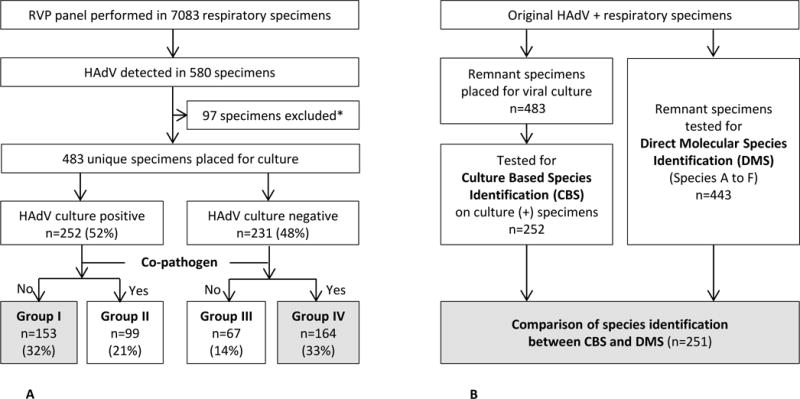

Figure 1.

A. Schematic Flowchart of Patient Enrollment and Case Classification

Group I was considered most consistent with acute HAdV associated infection and Group IV was considered most consistent with incidental detection of HAdV.

*32 patients had ≥ 2 episodes of HAdV detection during study period and 9 patients were immunocompromised hosts.

B. Schematic Flowchart of Testing for Species Identification

Abbreviations: RVP, respiratory virus PCR; HAdV, Human Adenovirus; CBS, Culture Based Species Identification; DMS, Direct Molecular Species Identification

Housekeeping gene

In order to evaluate specimen quality, we examined the cellularity of the original respiratory samples by determining the relative level of a two-copy human house-keeping gene, Zink finger 80 (ZnF80, 3q13.31) in each sample25.

Clinical phenotypes

Patients were classified using chart review based on their primary clinical syndrome at the time of testing for HAdV into clinical phenotypes:

Fever alone with no other specific signs or symptoms.

Upper respiratory tract illness (URTI) was defined as upper respiratory symptoms such as cough, coryza, conjunctivitis, pharyngitis with or without exudate, and/or pharyngoconjunctival fever.

Lower respiratory tract illness (LRTI) was defined as acute respiratory illness with symptoms or signs of lower airway involvement (e.g., dyspnea or tachypnea, hypoxia, and/or abnormal lung examination).

Gastrointestinal illness was defined as gastroenteritis (only if diarrhea was a predominant complaint) or radiologically proven intussusception.

Sepsis-like syndrome was defined as hemodynamic instability with greater than 1 organ dysfunction.

Unclassified disease was noted for patients with insufficient documentation to classify illness phenotype.

Adenovirus Group definitions

Patients were classified into 4 Groups based on the ability to recover HAdV in culture and co-infection status. Viral co-infection was defined as detection of a respiratory virus using standard RVP which was performed in all specimens. Bacterial co-infection was defined as bloodstream infection with a pathogenic organism, culture proven skin/soft tissue infection, urinary tract infection as defined by American Academy of Pediatrics26, isolation or PCR detection of a pathogen in pleural fluid, or PCR NP detection of respiratory pathogens (Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Bordetella pertussis).

All patients had at least one symptom clinically compatible with HAdV-associated disease.

Group I: Patients with a PCR+ respiratory specimen, HAdV culture (+) and no identified co-pathogen.

Group II: Patients with a PCR+ respiratory specimen, HAdV culture (+) and a simultaneously identified co-pathogen (viral, bacterial, or fungal as previously described) which might also explain the clinical symptoms.

Group III: Patients with a PCR+ respiratory specimen, HAdV culture (−) and no identified co-pathogen.

Group IV: Patients with a PCR+ respiratory specimen, HAdV culture (−) and a co-pathogen which could account for the observed clinical symptoms alternatively.

For the purposes of this study, Group I was considered to be most consistent with acute HAdV disease and Group IV was considered to be most consistent with incidental detection.

Statistical analysis

Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for comparisons between two or several groups as appropriate, and Chi square test was used for proportions. A two-tailed p value <0.05 was considered significant. All analysis, including receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism, (San Diego, CA).

Results

Adenovirus Case Classifications and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 7083 specimens (99% NP swabs, and 1% from eye, throat swabs or pooled specimens) were tested by RVP. HAdV was detected in 483 unique patients who were classified into 4 Groups according to our case definition (Fig.1A). The majority of patients (416, 86%) were < 5 years of age. Clinical characteristics of each Group are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Adenovirus (HAdV) Patients by Group Classification

| Case Classification | Total N=483 |

Group I Δ n=153 (32%) |

Group II n=99 (21%) |

Group III n=67 (14%) |

Group IV Δ n=164 (33%) |

P* | P Δ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Clinical Characteristics | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Age (month, median) (IQR) | 18.4 (8.4–38) | 29.8 (11.3–57.6) | 11.1 (5.9–20.3) | 19.5 (8.4–36.7) | 16.7 (8.3–31.4) | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Male : Female ratio | 1.3:1 | 1.1:1 | 1.7:1 | 1.8:1 | 1.2:1 | ||

| Underlying condition (%) | 185 (38) | 42 (27) | 35 (36) | 32 (48) | 76 (46) | .002 | .0008 |

| Patient location | |||||||

| Outpatient (%) | 153 (32) | 69 (45)) | 32 (32) | 23 (34) | 29 (18)) | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| ICU (%) | 91 (19) | 8 (5 | 23 (23) | 12 (18) | 48 (29 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Length of stay (median days) | 2 | 2.2 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 2.5 | NS | NS |

| Patients with fever (%) | 335 (69) | 137 (90) | 65 (65) | 44 (66) | 89 (54) | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Duration of fever (median days prior to HAdV testing) | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1.5 | 2 | .003 | .013 |

| Clinical Phenotype (%) | |||||||

| URTI | 223 (46) | 106 (69) | 39 (39) | 36 (54) | 42 (26) | ||

| LRTI | 204 (42) | 24 (16) | 53 (54) | 23 (35) | 104 (63) | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Fever alone | 27 (6) | 10 (7) | 1 (1) | 3 (4) | 13 (8) | ||

| Othersa | 29 (6) | 13 (8) | 6 (6) | 5 (7) | 5 (3) | ||

| Co-pathogen (%) | 265 (55) | ||||||

| Virus only | 243 (92) | NA | 95 (96) | NA | 146 (89) | ||

| Bacteria and/or fungus | 22 (8) | NA | 4 (4) | NA | 18 (11) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Virologic Characteristics | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| HAdV Cts, median (IQR) | 32.1 (25.1–37.4) | 23.9 (22.2–28.1) | 27.8 (24.7–31.7) | 37.6 (34.5–38.5) | 37.3 (35.3–38.9) | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| HAdV species (%) | |||||||

| C | 307 (67) | 65 (41) | 83 (83) | 46 (82) | 113 (83) | ||

| B | 103 (21) | 81 (53) | 14 (14) | 3 (5) | 5 (4) | ||

| F | 26 (5) | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 4 (7) | 19 (14) | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Others (A, E or D) | 21 (4) | 10 (7) | 3 (3) | 3 (5) | 5 (3) | ||

| 2 species | 14 (3) | 6b (4) | 2c (2) | 0 (0) | 6d (4) | ||

| NAe | 40 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 28 | ||

Abbreviation: HAdV, Human Adenovirus; URTI, upper respiratory tract illness; LRTI, lower respiratory tract illness; Ct, cycle threshold; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable

12 with GI illness (9; gastroenteritis, 3; intussusception), 2 with sepsis like syndrome, 15 unclassified

3 C+F, 2 B+C, 1 E+C,

2 C+A,

1 B+D, 2 C+F, 1 B+C, 2 B+C

Specimens could not be identified by DMS or specimen could not be found for DMS (n=1).

Kruskal-Wallis Test or Chi-square test for all Groups

Mann-Whitney Test, Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for Groups I and IV

Adenovirus Cases and Ct values

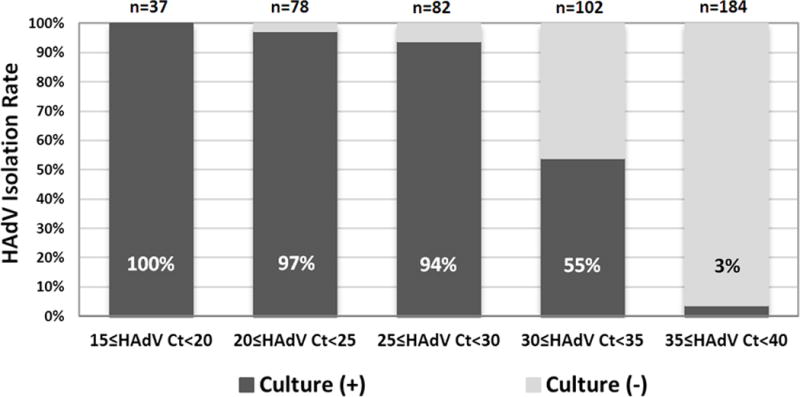

Ct values vs. viral isolation rates

The relationship between HAdV Cts and culture isolation rates are shown in Fig. 2. HAdV Cts of culture (+) Groups (Groups I and II; median Ct 25.8 [IQR 22.5–29.9]) were significantly lower than those from culture (−) Groups (Groups III and IV; median 37.4 [IQR 35.2–38.8], p<.0001). Additionally, we compared clinical and virologic characteristics of the patients whose respiratory specimens were culture (+) and had low viral burden (HAdV Cts >30, n=62) from those with culture (−) and high viral burden (HAdV Cts ≤30, n=7). There was no difference in age, days of fever, clinical phenotype, Ct of housekeeping gene, co-infection status or predominance of one HAdV species between these two subpopulations.

Fig 2. HAdV Ct values versus Isolation Rates.

A total of 245 (97%) of specimens that were culture positive had a corresponding NP Ct of <35 (p<0.0001).

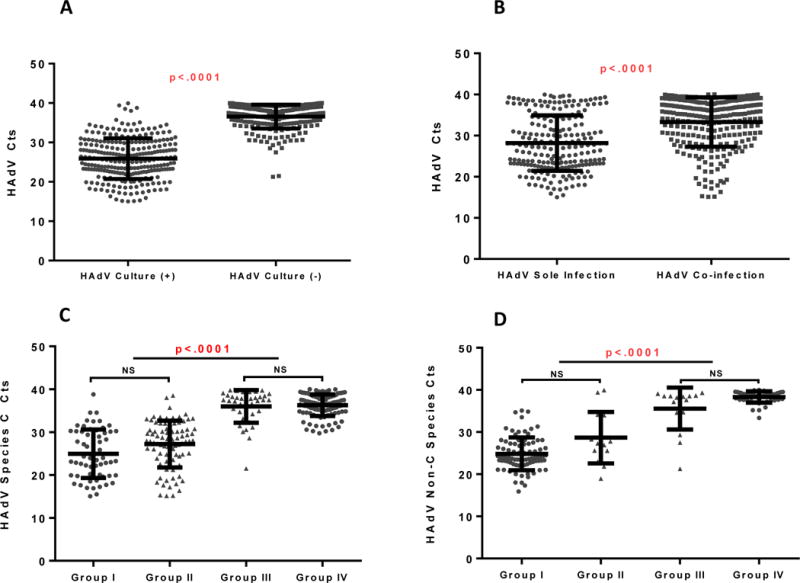

Ct values in sole HAdV detection vs. Co-infection

HAdV Ct values for each Group according to case definitions are shown in Table 1. Cts in sole HAdV detection Groups (Groups I and III; median Ct 27.2 [IQR 23–34.6]) were significantly lower than those in co-infection Groups (Groups II and IV; median Ct 35.2 [IQR 30–38.1], p<.0001). Median Ct values for HAdV-C and non C species in each group are shown in Figure 3A and 3B. Because of the known high detection rate of HRV/EV among asymptomatic children, we examined the median HAdV Cts in the co-infection Groups (II and IV) among those in which the only co-infection was HRV/EV vs. other viral co-infections. There was no significant difference in median HAdV Cts among specimens with HRV/EV co-infection vs. co-infection with other respiratory viruses in Group II (median HAdV Ct 26.9 vs. 29.2, p=0.55). Similarly, there was no significant difference in median HAdV Cts among Group IV with co-infection with HRV/EV only vs. co-infection with other respiratory viruses (median HAdV Ct 37.2 vs 37.2, p>0.99).

Figure 3.

A. Ct values of HAdV culture (+) group vs HAdV culture (−) group

Median Cts (IQR): HAdV culture (+) group 25.8 (22.5–29.9), HAdV culture (−) group 37.4 (35.2–38.8)

B. Ct values of HAdV sole infection group vs HAdV co-infection group

Median Cts (IQR): HAdV sole infection group 27.2 (23–34.6), HAdV co-infection group 35.2 (30–38.1)

C. Ct values of HAdV-C In Each Group

Median Cts (IQR) in each group: Group I 24.0 (19.9–30.1), Group II 28.0 (24.4–30.7), Group III 37.5 (34.2–38.5) Group IV, 36.6 (34.9–38.2)

D. Ct values of non HAdV-C Species By Group

Median Cts (IQR) in each group: Group I 23.8 (22.8–27.2), Group II 26.9 (25.2–33.9), Group III 38.2 (34.12–38.6), Group IV 38.1 (37.6–39.3)

HAdV Species Identification

Culture Based Species Identification (CBS)

HAdV-C and -B were identified in the majority (243/252, 96%) of CBS samples. In Group I, HAdV-B was predominant (53%), while HAdV-C was predominant (83%) in Group II (Table 1).

Direct Molecular Species Identification (DMS)

For specimens which were culture-negative and for which the only available species identification was via DMS (n=191), HAdV-C was predominant (n=159, 83%) followed by HAdV-F (n=23, 12%). Two or more HAdV species were identified in 6 culture negative specimens (Table 1).

Correlation between CBS and DMS

There was 100% concordance between results obtained by CBS and DMS for species identification. The DMS identified additional HAdV species in 8 culture positive specimens (Table. 1).

Human-House Keeping Gene

Median Ct values for the housekeeping gene for each Group were within 1 Ct difference of one another: Group I, 25.2 (IQR 24.2–26.4); Group II, 24.6 (IQR 23.6–26.1); Group III, 24.7 (IQR 23.9–25.6); Group IV, 25.1 (IQR 24.3–26.4).

Adenovirus detection In Asymptomatic, Healthy Children

Two (4%) out of 48 NP specimens from asymptomatic healthy children (median age 119 months, IQR 45.5–157.2 months) were positive for HAdV. One specimen was identified as HAdV-C with a Ct of 33.1 and the other was non-typeable with a Ct of 38.8. Neither subject had any co-detection of other respiratory virus.

Characteristics of Unique Patient Populations

Patients with identified viral co-infection

In the co-infection Groups (Groups II and IV, n=265), there were 239 specimens in which HAdV was co-detected with other respiratory viruses. The most frequent co-detections were HRV/EV (43%), RSV (42%), PIV (9%), hMPV (5%), and Flu A/B (3%).

Patients with identified bacterial and/or fungal co-pathogens

Twenty-two (8%) patients had concomitant bacterial and/or fungal infections identified at the time of HAdV detection (Table 2). Of 22 patients, 18 patients (81%; cases 1–18) were classified as Group IV with a median Ct of 37.3 (IQR 34–39). There were 4 patients with relatively lower Ct (median Ct 27.9) classified as Group II (cases 19–22). Of 22 patients, 10 patients had bacteremia/fungemia or urinary tract infection; all had high Cts ≥35 and HAdV-C was identified in all specimens when DMS was successful.

Table 2.

Adenovirus (HAdV) Cases with Identified Bacterial and/or Fungal Co-pathogens

| Clinical Characteristics | Viral Characteristics | Copathogen | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(month)/Sex | Underlying Conditions | Clinical Phenotype | Case Classification | HAdV Cts | HAdV Species | Bacterial/Fungal organism | Source | |

| Case 1 | 55.4/F | Fever only | Group IV | 37.4 | C | S. pyogenes | Blood | |

| Case 2 | 17/F | Fever only | Group IV | 36.1 | C | S. pneumoniae | Blood | |

| Case 3 | 8.4/F | Sickle cell disease | Fever only | Group IV | 39.9 | NA | E. coli | Urine |

| Case 4 | 20.1/F | Traumatic brain injury | Fever only | Group IV | 37.2 | C | E. coli | Urine |

| Case 5 | 26.2/F | Reactive airway disease | Fever only | Group IV | 39.7 | NA | E. coli | Urine |

| Case 6 | 40.1/F | History of BPD | Fever only | Group IV | 39.8 | C | P. aeruginosa | Urine |

| Case 7 | 53/M | Cornelia De Lange | Fever only | Group IV | 37.3 | NA | E. faecalis | Urine |

| Case 8 | 6.1/M | History of BPD | Fever only | Group IV | 31.2 | C | S. aureus | Abscess |

| Case 9 | 57/M | TPN dependent, reactive airway disease | Fever only | Group IV | 38.5 | F | S. aureus | Abscess |

| Case 10 | 38.5/M | TPN dependent | URTI | Group IV | 39.5 | NA | K. pneumoniae | Blood |

| Case 11 | 13.7/F | URTI | Group IV | 34.2 | C | S. aureus | Abscess | |

| Case 12 | 31.7/F | URTI | Group IV | 35.9 | C | M. pneumoniae | NP | |

| Case 13 | 89.5/M | URTI | Group IV | 38.9 | F | M. pneumoniae | NP | |

| Case 14 | 106.9/F | Cerebral palsy | LRTI | Group IV | 39.0 | C | S. pneumoniae | Blood |

| Case 15 | 27.4/F | Congenital heart disease | LRTI | Group IV | 37.6 | NA | E. faecalis C. glabrata | Blood |

| Case 16 | 199.1/M | Cerebral palsy | LRTI | Group IV | 39.5 | NA | S. aureus | Pleural fluid |

| Case 17 | 5.9/F | GI illness | Group IV | 37.1 | F | B. pertussis | NP | |

| Case 18 | 11.8/M | Unclassified | Group IV | 39.1 | C | B. pertussis | NP | |

| Case 19 | 3.9/M | URTI | Group II | 33.1 | C | B. pertussis | NP | |

| Case 20 | 6.6/F | History of BPD | URTI | Group II | 19.6 | C | B. pertussis | NP |

| Case 21 | 66.3/F | LRTI | Group II | 26.3 | B | M. pneumoniae | NP | |

| Case 22 | 34.1/M | LRTI | Group II | 29.6 | C | S. pneumoniae | Pleural fluid | |

Abbreviation: BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; URTI, upper respiratory tract illness; LRTI, lower respiratory tract illness; GI, gastrointestinal; Ct, cycle threshold; NP, nasopharynx; NA, not available (Specimens were not able to be identified to species level using molecular testing)

Infants younger than 60 days

A total of 9 patients were under 60 days at the time of HAdV detection with a median age of 37.4 days (IQR 25.1–43.9 days); 3 were late preterm infants (all gestational age of 36 weeks) and all infants were admitted secondary to respiratory symptoms (5 URTIs and 4 LRTIs). Only one patient (45 days old), who had HAdV-C (Ct 28.7) with HRV/EV and RSV co-infection, required ICU care with mechanical ventilator for 6 days due to LRTI. Sepsis-like syndrome was not observed in this small cohort. Two patients were classified to Group II (2 C), 3 to Group III (1 C, 1 F, 1 nontypeable), 4 to Group IV (3 F, 1 nontypeable) and overall median HAdV Ct was 38.1 (IQR 34.9–39.1).

Nasopharyngeal Ct values and ROC curve for growth in culture

To assess the relationship between semi-quantitative Ct values and the ability of specimens to grow in viral culture, an ROC curve was performed. Area under the ROC curve (AUC) for all Groups was 0.9549 (95% confidential interval (CI); 0.9362–0.9736, p <0.0001). When using only values from Groups I and IV, the AUC was 0.9827 (95% CI; 0.9707–0.9947, p <0.0001, Supplemental Figure 1A). We then performed a second ROC curve for the two most common species identified-HAdV-B and C. The AUC for species B was 0.9553 (95% CI; 0.9327–0.9778, p <0.0001) and HAdV-C was 0.9546 (95% CI; 0.9078–1.000, p <0.0001). ROC by subtype is shown in Supplemental Figure 1B.

Discussion

It is difficult to clearly distinguish incidental HAdV detection from acute HAdV associated disease in the absence of a longitudinal study. However, we were able to retrospectively classify patients based on virologic characteristics into categories that may shed light on the likelihood of HAdV attributable causality of disease. Since there is no established gold standard to diagnose acute HAdV disease, we utilized recovery of HAdV in culture as a marker of active disease because there is a much lower rate of asymptomatic detection in children using culture (0.6%)3 versus PCR (3–11%)10–12. Thus, culture provides a higher positive predictive value for acute disease than PCR detection alone. We first identified Group I (most consistent with acute disease) and Group IV (most consistent with incidental detection) as the most straightforward categories. Group I patients most likely had acute HAdV disease as they had compatible illnesses and HAdV identified using two different methods (PCR and viral culture). Group IV patients had an alternate explanation for their symptoms (viral or bacterial/fungal co-pathogen) and their specimens failed to yield an HAdV isolate in culture, making it more likely that the detection of HAdV represented an incidental detection rather than the primary cause of acute symptoms, especially when a high Ct of HAdV-C was identified. Two virologic criteria, when used together, were helpful to discriminate these two Groups. First, Cts were significantly lower in Group I than in Group IV (median Cts: 23.9 vs. 37.3, p<.0001). Second, HAdV-C was overrepresented in Group IV (83%) compared to Group I (41%, p<.0001).

HAdV-C is indeed a common cause of primary HAdV disease in young children3, 4, 27 but it is also known to be the most common HAdV species detected incidentally in pediatric tonsils and adenoids7, 8, 28. Specifically for HAdV-C, the semi-quantitative viral burden (Ct value) was helpful in distinguishing Group I from Group IV, as HAdV Cts were lower in Group I vs. Group IV (median Cts: 24.0 vs. 36.6, p<.0001). We also found differences in the positive predictive value of a given Ct for HAdV-B and C (the two most common HAdV species identified, Supplemental Figure 1B) for culture positivity, indicating that species and viral burden should be interpreted together; relatively higher Ct values still may be relevant for HAdV-B, but may not be as relevant for HAdV-C.

Although a similar significant difference in Cts was found between Groups II and III (median Ct 27.8 in Group II vs. 37.6 in Group III), the role of HAdV-C as the cause of disease was less clear in these two Groups. HAdV-C was also more predominant than HAdV-B in Group II (83%) with low Cts (median Ct: 28). Children in Group II were relatively young (median 11.1 months). We believe that HAdV-C was more common in this group because it causes acute primary disease at a younger age than HAdV-B4, 27 and co-infection with other respiratory viruses is more common in younger children29, 30, indicating that true acute co-infection of HAdV-C with HRV/EV or RSV is clearly possible. Group III remains the most challenging group to interpret, as there are several possibilities: 1) a recent HAdV infection with low viral burden in the respiratory tract, 2) specimen obtained during incubation period, 3) low-level persistence during another illness, or 4) an antecedent HAdV illness followed by a presumed bacterial illness such as acute otitis media or pneumonia, as previously described31–33.

One of the most concerning situations would be attribution of disease etiology to HAdV when there is a serious bacterial infection, so we examined this cohort specifically. The majority of these patients (81%) were classified as Group IV (most consistent with incidental detection). We found that HAdV semi-quantitative viral burden and species identification were especially helpful in the subgroup of patients with bloodstream or urinary tract infection (n=10, Table. 2). All of these patients’ specimens had Cts ≥35 and all typeable samples were identified as HAdV-C by DMS. We also noted 9 patients who had fever alone as their clinical phenotype, and the majority had HAdV-C or F with high Cts (cases 1–9, Table 2). Although the clinical significance of NP detection of HAdV-F (types 40/41) is still unclear34,35, it has been detected incidentally from pediatric respiratory samples28. Others have reported that HAdV can be associated with fever without localizing symptoms12, however our data suggest that attributing febrile illness to HAdV alone, specifically when HAdV-C or F is detected in the NP with low viral burden, requires a cautious interpretation.

We identified 9 infants < 60 days with HAdV infection. HAdV has been detected in amniotic fluid or placental tissue, thus the source of infection may have been through vertical or horizontal transmission after birth36, 37. Although this particular population is at high risk for severe or disseminated HAdV disease38, the majority of young infants (89%) did not demonstrate serious illness related to HAdV infection. The difference in this cohort vs. prior cohorts may be the method of identification of HAdV (highly sensitive PCR vs. viral culture/direct fluorescence antibody testing), the fact that the children were all term infants, or that the median age at the time of identification of HAdV infection was older than in prior cohorts. We also noted an over-representation of infections by HAdV-F (4 of 9 specimens, 44%) in young infants <60 days whose clinical phenotype was respiratory tract illness. Because HAdV-F is most frequently associated with gastro-intestinal illness, the clinical significance of detection of HAdV-F in infants with respiratory illness is unclear.

Our study has limitations. A negative HAdV culture does not necessarily exclude acute disease attributable to HAdV infection as it may be impacted by duration of illness at the time of sample collection. The retrospective clinical data collection did not allow for consistent documentation of exact duration of all symptoms, so we used timing of fever before HAdV testing to estimate the duration of illness. This study did not include longitudinal samples, so we could not evaluate the dynamics of HAdV detection during acute illness. Viral cultures were performed on stored frozen specimens and this could have impacted the preservation of virus infectivity, however we did note consistent cellularity of specimens using a human housekeeping gene, diminishing the likelihood that specimen quality affected results. The A549 cell line used for viral isolation does not easily support growth of HAdV-F (types 40 and 41)39, likely impacting results. However HAdV-F accounted for only 5% of the detected HAdV in the cohort. The specific Ct values calculated with our laboratory assay are not directly equivalent to those obtained with other PCR assays, but they are useful for improving the clinical interpretation of PCR-based HAdV testing.

The present data indicate that when PCR testing is used for diagnosis of HAdV infection and disease, there is a need for additional assays that provide both viral load quantitation and species identification to aid the interpretation of positive results. There are FDA-approved singleplex and multiplex PCR assays40–44 for diagnosis of respiratory viruses, but no FDA-approved test provides comprehensive HAdV species identification and viral load.

In conclusion, detection of HAdV in pediatric NP samples by PCR-based methods does not necessarily establish causality of disease. Although detection of HAdV-C is associated with acute disease, if it is detected with a low viral burden (high Ct) clinicians should consider the possibility of incidental detection. Both HAdV typing and viral load quantitation may be useful tools to assess the clinical significance of HAdV detection and should be considered as new assays are developed to improve the diagnosis of HAdV infections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Ms. Megan Sartain at Lovelace Respiratory Research Institute for assistance with virus culture and typing.

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No potential conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Fox JP, Hall CE, Cooney MK. The Seattle Virus Watch. VII. Observations of adenovirus infections. American journal of epidemiology. 1977;105(4):362–386. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandt CD, Kim HW, Vargosko AJ, Jeffries BC, Arrobio JO, Rindge B, et al. Infections in 18,000 infants and children in a controlled study of respiratory tract disease. I. Adenovirus pathogenicity in relation to serologic type and illness syndrome. American journal of epidemiology. 1969;90(6):484–500. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards KM, Thompson J, Paolini J, Wright PF. Adenovirus infections in young children. Pediatrics. 1985;76(3):420–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabain I, Ljubin-Sternak S, Cepin-Bogovic J, Markovinovic L, Knezovic I, Mlinaric-Galinovic G. Adenovirus respiratory infections in hospitalized children: clinical findings in relation to species and serotypes. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2012;31(7):680–684. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318256605e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaggi P, Kajon AE, Mejias A, Ramilo O, Leber A. Human adenovirus infection in Kawasaki disease: a confounding bystander? Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2013;56(1):58–64. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rocholl C, Gerber K, Daly J, Pavia AT, Byington CL. Adenoviral infections in children: the impact of rapid diagnosis. Pediatrics. 2004;113(1 Pt 1):e51–56. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.1.e51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garnett CT, Erdman D, Xu W, Gooding LR. Prevalence and quantitation of species C adenovirus DNA in human mucosal lymphocytes. Journal of virology. 2002;76(21):10608–10616. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.21.10608-10616.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garnett CT, Talekar G, Mahr JA, Huang W, Zhang Y, Ornelles DA, et al. Latent species C adenoviruses in human tonsil tissues. Journal of virology. 2009;83(6):2417–2428. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02392-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy S, Calcedo R, Medina-Jaszek A, Keough M, Peng H, Wilson JM. Adenoviruses in lymphocytes of the human gastro-intestinal tract. PloS one. 2011;6(9):e24859. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fairchok MP, Martin ET, Chambers S, Kuypers J, Behrens M, Braun LE, et al. Epidemiology of viral respiratory tract infections in a prospective cohort of infants and toddlers attending daycare. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2010;49(1):16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rhedin S, Lindstrand A, Rotzen-Ostlund M, Tolfvenstam T, Ohrmalm L, Rinder MR, et al. Clinical utility of PCR for common viruses in acute respiratory illness. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):e538–545. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colvin JM, Muenzer JT, Jaffe DM, Smason A, Deych E, Shannon WD, et al. Detection of viruses in young children with fever without an apparent source. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):e1455–1462. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calvo C, Garcia-Garcia ML, Blanco C, Santos MJ, Pozo F, Perez-Brena P, et al. Human bocavirus infection in a neonatal intensive care unit. The Journal of infection. 2008;57(3):269–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalu SU, Loeffelholz M, Beck E, Patel JA, Revai K, Fan J, et al. Persistence of adenovirus nucleic acids in nasopharyngeal secretions: a diagnostic conundrum. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2010;29(8):746–750. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181d743c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jansen RR, Wieringa J, Koekkoek SM, Visser CE, Pajkrt D, Molenkamp R, et al. Frequent detection of respiratory viruses without symptoms: toward defining clinically relevant cutoff values. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2011;49(7):2631–2636. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02094-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marin J, Jeler-Kacar D, Levstek V, Macek V. Persistence of viruses in upper respiratory tract of children with asthma. The Journal of infection. 2000;41(1):69–72. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2000.0688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maertzdorf J, Wang CK, Brown JB, Quinto JD, Chu M, de Graaf M, et al. Real-time reverse transcriptase PCR assay for detection of human metapneumoviruses from all known genetic lineages. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2004;42(3):981–986. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.3.981-986.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Templeton KE, Bredius RG, Scheltinga SA, Claas EC, Vossen JM, Kroes AC. Parainfluenza virus 3 infection pre- and post-haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: re-infection or persistence? Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2004;29(4):320–322. doi: 10.1016/S1386-6532(03)00215-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu X, Holloway B, Dare RK, Kuypers J, Yagi S, Williams JV, et al. Real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay for comprehensive detection of human rhinoviruses. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2008;46(2):533–539. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01739-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heim A, Ebnet C, Harste G, Pring-Akerblom P. Rapid and quantitative detection of human adenovirus DNA by real-time PCR. Journal of medical virology. 2003;70(2):228–239. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kajon AE, Dickson LM, Fisher BT, Hodinka RL. Fatal disseminated adenovirus infection in a young adult with systemic lupus erythematosus. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2011;50(1):80–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kajon AE, Dickson LM, Murtagh P, Viale D, Carballal G, Echavarria M. Molecular characterization of an adenovirus 3–16 intertypic recombinant isolated in Argentina from an infant hospitalized with acute respiratory infection. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2010;48(4):1494–1496. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02289-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Selvaraju SB, Kovac M, Dickson LM, Kajon AE, Selvarangan R. Molecular epidemiology and clinical presentation of human adenovirus infections in Kansas City children. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2011;51(2):126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lion T, Baumgartinger R, Watzinger F, Matthes-Martin S, Suda M, Preuner S, et al. Molecular monitoring of adenovirus in peripheral blood after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation permits early diagnosis of disseminated disease. Blood. 2003;102(3):1114–1120. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoebeeck J, van der Luijt R, Poppe B, De Smet E, Yigit N, Claes K, et al. Rapid detection of VHL exon deletions using real-time quantitative PCR. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 2005;85(1):24–33. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finnell SM, Carroll AE, Downs SM. Technical report-Diagnosis and management of an initial UTI in febrile infants and young children. Pediatrics. 2011;128(3):e749–770. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang SL, Chi CY, Kuo PH, Tsai HP, Wang SM, Liu CC, et al. High-incidence of human adenoviral co-infections in taiwan. PloS one. 2013;8(9):e75208. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alkhalaf MA, Guiver M, Cooper RJ. Prevalence and quantitation of adenovirus DNA from human tonsil and adenoid tissues. Journal of medical virology. 2013;85(11):1947–1954. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mansbach JM, Piedra PA, Teach SJ, Sullivan AF, Forgey T, Clark S, et al. Prospective multicenter study of viral etiology and hospital length of stay in children with severe bronchiolitis. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2012;166(8):700–706. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wishaupt JO, Versteegh FG, Hartwig NG. PCR testing for paediatric acute respiratory tract infections. Paediatric respiratory reviews. 2015;16(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chonmaitree T, Revai K, Grady JJ, Clos A, Patel JA, Nair S, et al. Viral upper respiratory tract infection and otitis media complication in young children. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2008;46(6):815–823. doi: 10.1086/528685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chonmaitree T, Alvarez-Fernandez P, Jennings K, Trujillo R, Marom T, Loeffelholz MJ, et al. Symptomatic and asymptomatic respiratory viral infections in the first year of life: association with acute otitis media development. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2015;60(1):1–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cevey-Macherel M, Galetto-Lacour A, Gervaix A, Siegrist CA, Bille J, Bescher-Ninet B, et al. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized children based on WHO clinical guidelines. European journal of pediatrics. 2009;168(12):1429–1436. doi: 10.1007/s00431-009-0943-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Echavarria M, Maldonado D, Elbert G, Videla C, Rappaport R, Carballal G. Use of PCR to demonstrate presence of adenovirus species B, C, or F as well as coinfection with two adenovirus species in children with flu-like symptoms. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2006;44(2):625–627. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.2.625-627.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pehler-Harrington K, Khanna M, Waters CR, Henrickson KJ. Rapid detection and identification of human adenovirus species by adenoplex, a multiplex PCR-enzyme hybridization assay. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2004;42(9):4072–4076. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.9.4072-4076.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsekoura EA, Konstantinidou A, Papadopoulou S, Athanasiou S, Spanakis N, Kafetzis D, et al. Adenovirus genome in the placenta: association with histological chorioamnionitis and preterm birth. Journal of medical virology. 2010;82(8):1379–1383. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reddy UM, Baschat AA, Zlatnik MG, Towbin JA, Harman CR, Weiner CP. Detection of viral deoxyribonucleic acid in amniotic fluid: association with fetal malformation and pregnancy abnormalities. Fetal diagnosis and therapy. 2005;20(3):203–207. doi: 10.1159/000083906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ronchi A, Doern C, Brock E, Pugni L, Sanchez PJ. Neonatal adenoviral infection: a seventeen year experience and review of the literature. The Journal of pediatrics. 2014;164(3):529–535 e521–524. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim M, Lim MY, Ko G. Enhancement of enteric adenovirus cultivation by viral transactivator proteins. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2010;76(8):2509–2516. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02224-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andersson ME, Olofsson S, Lindh M. Comparison of the FilmArray assay and in-house real-time PCR for detection of respiratory infection. Scandinavian journal of infectious diseases. 2014;46(12):897–901. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2014.951681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruggiero P, McMillen T, Tang YW, Babady NE. Evaluation of the BioFire FilmArray respiratory panel and the GenMark eSensor respiratory viral panel on lower respiratory tract specimens. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2014;52(1):288–290. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02787-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Babady NE, Mead P, Stiles J, Brennan C, Li H, Shuptar S, et al. Comparison of the Luminex xTAG RVP Fast assay and the Idaho Technology FilmArray RP assay for detection of respiratory viruses in pediatric patients at a cancer hospital. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2012;50(7):2282–2288. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06186-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poritz MA, Blaschke AJ, Byington CL, Meyers L, Nilsson K, Jones DE, et al. FilmArray, an automated nested multiplex PCR system for multi-pathogen detection: development and application to respiratory tract infection. PloS one. 2011;6(10):e26047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loeffelholz MJ, Pong DL, Pyles RB, Xiong Y, Miller AL, Bufton KK, et al. Comparison of the FilmArray Respiratory Panel and Prodesse real-time PCR assays for detection of respiratory pathogens. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2011;49(12):4083–4088. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05010-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.