Significance

The prevailing view of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (Nrf2) function in the central nervous system is that it acts by a cell-nonautonomous mechanism to activate a program of gene expression that mitigates reactive oxygen species and the damage that ensues. Our work significantly expands the biological understanding of Nrf2 by showing that Nrf2 mitigates toxicity induced by α-synuclein and leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2), by potently promoting neuronal protein homeostasis in a cell-autonomous and time-dependent fashion. Nrf2 accelerates the clearance of α-synuclein, shortening its half-life and leading to lower overall levels of α-synuclein. By contrast, Nrf2 promotes the aggregation of LRRK2 into inclusion bodies, leading to a significant reduction in diffuse mutant LRRK2 levels elsewhere in the neuron.

Keywords: Nrf2, Parkinson’s disease, LRRK2, α-synuclein, proteostasis

Abstract

Mutations in leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) and α-synuclein lead to Parkinson’s disease (PD). Disruption of protein homeostasis is an emerging theme in PD pathogenesis, making mechanisms to reduce the accumulation of misfolded proteins an attractive therapeutic strategy. We determined if activating nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (Nrf2), a potential therapeutic target for neurodegeneration, could reduce PD-associated neuron toxicity by modulating the protein homeostasis network. Using a longitudinal imaging platform, we visualized the metabolism and location of mutant LRRK2 and α-synuclein in living neurons at the single-cell level. Nrf2 reduced PD-associated protein toxicity by a cell-autonomous mechanism that was time-dependent. Furthermore, Nrf2 activated distinct mechanisms to handle different misfolded proteins. Nrf2 decreased steady-state levels of α-synuclein in part by increasing α-synuclein degradation. In contrast, Nrf2 sequestered misfolded diffuse LRRK2 into more insoluble and homogeneous inclusion bodies. By identifying the stress response strategies activated by Nrf2, we also highlight endogenous coping responses that might be therapeutically bolstered to treat PD.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressively debilitating neurodegenerative condition that leads to motor and cognitive dysfunction. There are no disease-modifying therapies for this disease. Mutations in the genes encoding α-synuclein (1) and leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) cause PD (2). Mutations in LRRK2 are the most common genetic cause of PD (3), and although mutations in α-synuclein are rare, abnormal α-synuclein accumulation and pathology characterize most PD cases (4). Furthermore, there is evidence of an epistatic relationship between LRRK2 and α-synuclein (5–7), suggesting that understanding how to block their ability to cause neurodegeneration might be beneficial across a wide swath of PD patients.

Mutations in both proteins have been implicated in protein misfolding and protein dyshomeostasis within the cell (8). Mechanisms to handle misfolded proteins more effectively within the cell include modulating endogenous cellular stress response pathways that up-regulate the protein degradation machinery or sequester the misfolded proteins into inclusion bodies (IBs) (9, 10). Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (Nrf2) coordinates a whole program of gene expression that counters stress at multiple levels (11). Nrf2 was initially shown to bind to the antioxidant responsive element (ARE) and regulate the expression of detoxification genes (e.g., GST) (12) and oxidative stress-inducible enzymes (e.g., heme oxygenase-1) (13), in response to electrophilic and reactive oxygen species-producing agents. However, growing evidence indicates that Nrf2 regulates a much broader gene expression response, including genes involved in protein homeostasis, such as chaperones and proteasome subunits (14–16), and thus, it is a potential target to deal with damaged proteins. It remains unknown if Nrf2 mediates a protective effect on different misfolded proteins by activating similar or divergent pathways.

Nrf2 mitigates neurodegeneration in genetic and toxin models of PD (17), and loss of Nrf2 exacerbates degeneration (12), implicating it as a potential therapeutic target of PD (18). Interestingly, the protective effect of Nrf2 is often mediated by expression of Nrf2 in astrocytes (19, 20), which supports a predominantly non–cell-autonomous mechanism of neuronal protection. Whether this protective effect by Nrf2 can be mediated directly in neurons has yet to be determined. Using a single-cell longitudinal imaging platform, we demonstrate that Nrf2 expression in neurons directly mitigates toxicity induced by α-synuclein and mutations in LRRK2 and that this effect is time-dependent. We visualized the metabolism and localization of α-synuclein and mutant LRRK2 at the level of a single cell. Nrf2 expression reduced α-synuclein levels by increasing the degradation of α-synuclein. In contrast, the reduction of mutant LRRK2 toxicity by Nrf2 was associated with an increased risk of IB formation and more insoluble and homogeneous IBs. The sequestering of LRRK2 into more compact IBs led to a drop in diffuse LRRK2 levels elsewhere in the cell. By shedding light on how Nrf2 mediates its protective effect on PD-associated protein toxicity, we also shed light on endogenous coping responses that might be bolstered to handle misfolded proteins.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and Compounds.

Information on the plasmids and compounds used are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Cell Culture, Transfections, Immunocytochemistry, and Immunoblotting.

Experimental details are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Robotic Microscope Imaging System and Image Analysis.

For neuronal survival analysis, images of neurons were taken at 12–24-h intervals after transfection with an automated imaging platform as described (21–23). Further information on image acquisition and image analysis is provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Statistical Analysis.

With longitudinal single-cell data collected by tracking individual neurons over time, survival analysis was used to accurately determine differences in longevity between populations of cells (24). Further information on the statistical approaches used is provided in SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

Plasmids and Compounds.

The mammalian expression constructs pGW1-Venus LRRK2, pGW1-Venus-G2019S LRRK2, pGW1-Venus-Y1699C LRRK2 (5), pCAGGS–α-synuclein (29), and pEF-Nrf2 and ARE-Luc (18) were previously described. The synapsin_GFP construct was synthesized with the human synapsin promoter fused to GFP. The Luc gene was cloned out of the ARE-Luc plasmid and replaced with mApple. α-Synuclein was cloned into pGW1-Dendra2 [originally from pDendra2-C (Evrogen)] to make pGW1–Dendra2–α-synuclein. All constructs were verified by sequencing. In cotransfection experiments, pGW1-Venus-LRRK2 was cotransfected with either pGW1-mRFP (21) or pGW1-mApple as a survival marker. Nrf2 inducer tBHQ and autophagy inducers MTM and FPZ were acquired from Sigma. tBHQ was solubilized in ethanol and added to the cells 4–6 h posttransfection. All autophagy-inducing compounds were solubilized in DMSO and added to the primary neurons after transfection. Fresh aliquots of compounds were used in each independent experiment.

Cell Culture.

HEK293 cells were grown in DMEM containing 10% calf serum, 2 mM glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin (100 U·mL−1/100 μg·mL−1). HEK293 cells were transfected with plasmids by Lipofectamine 2000. Rat primary cultures of cortical neurons were dissected from rat pup cortices at embryonic days (E) 20–21. Brain cortices were dissected in dissociation medium (DM) with kynurenic acid (1 mM final) (DM/KY). DM was made from 81.8 mM Na2SO4, 30 mM K2SO4, 5.8 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM CaCl2, 1 mM Hepes, 20 mM glucose, 0.001% phenol red, and 0.16 mM NaOH. The 10× KY solution was made from 10 mM KY, 0.0025% phenol red, 5 mM Hepes, and 100 mM MgCl2. The cortices were treated with papain (100 U, Worthington Biochemical) for 10 min, followed by treatment with trypsin inhibitor solution (15 mg/mL trypsin inhibitor; Sigma) for 10 min. Both solutions were made up in DM/KY, sterile filtered, and kept in a 37 °C water bath. The cortices were then gently triturated to dissociate single neurons in Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and glucose medium (20 mM). Primary neurons were plated at 0.1 × 106 cells per well of a 96-well plate; 2 h later, the plating medium was replaced with Neurobasal growth medium with 100× GlutaMAX, Pen/Strep, and B27 supplement (NB medium).

iPSC Differentiation to DA Neurons.

iPSC lines derived from a health control individual were obtained from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke iPSC repository at Coriell Institute. Reprogramming and characterization of the iPSC line (normal female, 21 y old; CS83iCTR-33nxx) were previously reported (58). iPSCs were differentiated into forebrain neurons using a dual Smad differentiation protocol as described (59). At ∼30–35 d of differentiation, the cells were dissociated using trypsin (Sigma) and plated onto Matrigel (Corning)-coated 96-well plates. From day 30–35, the neurons underwent a half medium change every 2–3 d.

Transfections.

At 4–5 d in vitro (DIV), rat cortical neurons were transfected with plasmids and Lipofectamine 2000. Before adding the lipofectamine–DNA mix, cells were incubated in Neurobasal with 10× KY (as described above) to block glutamate receptors and reduce excitotoxic cell death during the transfection. For survival analysis, primary rat cortical neurons in 96-well plates were cotransfected with either pGW1-RFP or pGW1-mApple and pGW1-Venus-LRRK2 (0.8 μg of DNA per well) or pGW1-RFP and pCAGGS–α-synuclein (0.2–0.4 μg of DNA per well) or pCAGGS–Dendra2–α-synuclein (0.2–0.4 μg of DNA per well) and either pEF_empty or pEF_Nrf2 (0.01 μg of DNA per well). The primary neurons were incubated in the lipofectamine–DNA mix for 20–40 min. The neurons were then washed with Neurobasal and cultured in NB medium.

Human neurons were transfected at 38–42 d of differentiation with Lipofectamine 3000. The lipofectamine–DNA was added directly to the neurons without changing the medium and incubated on the cells for 24 h, after which a full medium change was made. For survival analysis, primary human neurons were cotransfected with pGFP_synapsin, pCAGGS–α-synuclein (0.3 μg of DNA per well), or pCAGGS-empty (0.3 μg of DNA per well) and either pEF_empty or pEF_Nrf2 (0.01 μg of DNA per well). The ReadyProbes Cell Viability assay (ThermoFisher) was used to test if loss of red fluorescent signal corresponds with cell death. Primary neurons were transfected with an RFP and treated with the viability stain 72 h later. The neurons were then imaged longitudinally over several days to capture the death of the neurons. To stain nuclei in live cells, neurons were treated with NucBlue (1:150, Molecular Probes) at 48 h posttransfection. To assess the detergent resistance of IBs, neurons were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at 37 °C, rinsed twice with PBS, and treated with 2.5% Triton X-100 and 2.5% SDS for 20 min at 37 °C (44). Neurons were then rinsed with PBS and imaged by fluorescence microscopy. For confocal analysis, cortical neurons were transfected and fixed 24–72 h posttransfection and imaged using a spinning-disk confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM510).

Immunocytochemistry.

For immunocytochemistry, cortical rat neurons were grown on 96-well plates or 12-mm coverslips. Neurons were transfected at 4 DIV. At 24–48 h posttransfection, immunocytochemistry was performed as described in ref. 5 and labeled with either anti-Nrf2 (1:200, Santa Cruz), anti-proteasome 20s alpha (1:50, Abcam), anti-GST (1:100, Abcam), synaptophsyin (1:200, Abcam), or anti–α-synuclein 1 (1:1,000, BD Transduction Laboratories) and then labeled with secondary antibodies, anti-rabbit Cy5-labeled antibodies (1:200, Jackson Immunoresearch), anti-rabbit Cy2-labeled antibodies (1:1,000, Jackson Immunoresearch), or anti-rabbit Cy3 (1:500, Jackson Immunoresearch).

Robotic Microscope Imaging System and Image Analysis.

Measurements of LRRK2 or α-synuclein expression, LRRK2 IB formation, and neuron survival were obtained from files generated by automated imaging. Digital images were analyzed with Metamorph, ImagePro, and original proprietary programs that were written in Matlab or pipeline pilot. These custom-based algorithms were used to capture and analyze neurons in each group in a high-throughput and unbiased manner. Live-transfected neurons were selected for analysis based on fluorescence intensity and morphology. Neurons were only selected if they had extended processes at the start of the experiment. The abrupt loss of mRFP or Dendra2-green fluorescence was used to estimate the survival time of the neuron (21). Steady-state levels of LRRK2 or α-synuclein were estimated by measuring Venus or Dendra2-green fluorescence intensity over a region of interest that corresponded to the cell soma. In the case of Venus-LRRK2–transfected cells, the fluorescence of cotransfected mRFP was used as a morphology marker (21). Venus and Dendra2-GFP intensity values were background-subtracted by using an adjacent area of the image. To measure the degradation of α-synuclein, neurons were cotransfected with pGW1-Venus, pGW1–Dendra2–α-synuclein, and either Nrf2 or empty vector. Approximately 24 h posttransfection, Dendra2–α-synuclein was photoswitched with a 1–2-s pulse of light at 405-nm wavelength. Dendra2–α-synuclein only fluoresced green with no detectable red fluorescence; however, upon photoswitching, a population of the green protein is irreversibly switched to emit red fluorescence. We then imaged the cells for red fluorescence (Dendra2-red) every 8 h for the next 2 d. The Dendra2-red fluorescence intensity was measured in each individual neuron at each time using a region of interest that corresponded to the cell soma. The cotransfected Venus provided the morphology mask for the cell soma.

Statistical Analysis.

For longitudinal survival analysis, the survival time of a neuron was defined as the time at which it was last seen alive. The survival package for R statistical software was used to construct Kaplan–Meier curves from the survival data. Survival functions were fitted to these curves and used to derive cumulative survival and risk-of-death curves that describe the instantaneous risk of death for individual neurons in the cohort being tracked. P values were derived using the Peto and Peto modification of the Gehan–Wilcoxon test. CPH regression analysis (Cox analysis) was used to quantify the relative risk of death between two cohorts of neurons and any time-dependent effects. In the Cox model that determined the effect of Nrf2 and time in neurons transfected with α-synuclein or control, the covariate for time was logged. HRs and their respective P values were generated using the coxph function in the survival package for R statistical software. All Cox models were analyzed for violations of proportional hazards using cox.zph functions in R.

For risk of IB formation, death can preclude and, therefore, have a competitive effect on the risk of IB formation. To control for this, HRs and P values for the risk of IB formation were determined with a multivariate regression analysis with the semiparametric proportional hazards model that incorporates the presence of competing risk events (competing risk analysis). The analysis was performed using the crr package for R statistical software. Identification and quantification of IB formation were based on expression intensity of Venus-LRRK2 and localization as described (5). Images of cells that were out of the focal plane of Venus fluorescence were excluded from analysis for IB formation (this was less than 1–5% of cells under analysis). The cumulative risk of IB formation curves were the estimated cumulative subdistribution hazard for IB formation and were derived from the competing risk regression model. Significance was derived from the competing risks proportional hazard regression model.

To compare differences across two groups, the groups were statistically compared using an unpaired t, Mann–Whitney, or Kruskal–Wallace tests. Differences across multiple groups were statistically compared using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test. Time-specific fluorescence changes in neurons that were followed over time were tested with the generalized estimating equations using the geese function in the geepack R package. Differences in mean fluorescence at select time points were tested using the contrast function in the contrast R package. P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Holm correction method.

To measure the degradation of α-synuclein, RFP fluorescence was measured longitudinally in each cell for 80 h or until the cell died. A Bayesian hierarchical model was used to analyze the underlying changes in RFP fluorescence in Dendra2–α-synuclein-expressing neurons. With Bayesian analysis, statistical inferences are based on posterior distributions (the probability distribution of the variables of interest, given the observed data). For each neuron, RFP fluorescence at each time point was normalized to its starting RFP fluorescence and logged. We assumed that the log RFP fluorescence values were normally distributed. Posterior computations were carried out through Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) via the rjags package for R (R Development Core Team and rjags: Bayesian graphical models using MCMC, R package version 3.1.0). The posterior distributions were used to estimate the slopes of RFP fluorescence and to make direct probability statements about the relative size of the effect of Nrf2, MTM, and FPZ on the decline of α-synuclein in primary neurons.

Results

Nrf2 Overexpression Reduces LRRK2- and α-Synuclein–Induced Toxicity in Primary Rat Neurons.

To elucidate a role for Nrf2 in cellular coping mechanisms for misfolded proteins, we developed a method to assay Nrf2 activation in live cells, including neurons. A common method to identify Nrf2 activation is through a reporter construct that contains the ARE (25) located in target genes of Nrf2. We adapted this approach by visualizing Nrf2 activation in real time in single cells by placing the expression of the fluorescent protein mApple under the control of the ARE sequence. To validate the ARE_mApple reporter gene, HEK293 cells were cotransfected with Venus, as a morphology marker, and ARE_mApple and treated with tertiary butylhydroquinone (tBHQ), an activator of endogenous Nrf2 (26). At 24 h posttransfection, cells were imaged, and ARE_mApple fluorescence was measured. Treatment with increasing doses of tBHQ caused a dose-dependent increase in ARE_mApple expression, indicative of ARE activation (Fig. S1A). Next we cotransfected HEK293 cells with Venus as a morphology marker, ARE_mApple, and either Nrf2 or empty vector and confirmed that overexpression of Nrf2 led to a robust activation of the ARE reporter in HEK293 cells (Fig. 1 A and B).

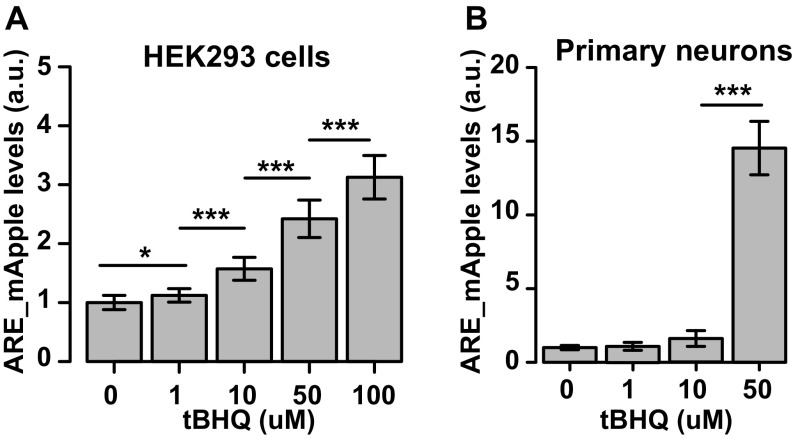

Fig. S1.

(A) HEK293 cells transfected with the ARE reporter show an increase in ARE_mApple fluorescence 24 h after treatment with increasing doses of tBHQ. Fold induction is normalized to control. Mean ± 95% CIs, calculated from three independent experiments. Number of cells in each group was >1,200; F value = 935.5, df = 4. *P = 0.011, ***P < 0.0001. (B) Primary rat neurons transfected with ARE show an increase in ARE_mApple fluorescence 24 h after treatment with tBHQ. Mean ± 95% CIs, calculated from three independent experiments. Number of neurons in each group was >780; F value = 1,477, df = 3. ***P < 0.0001.

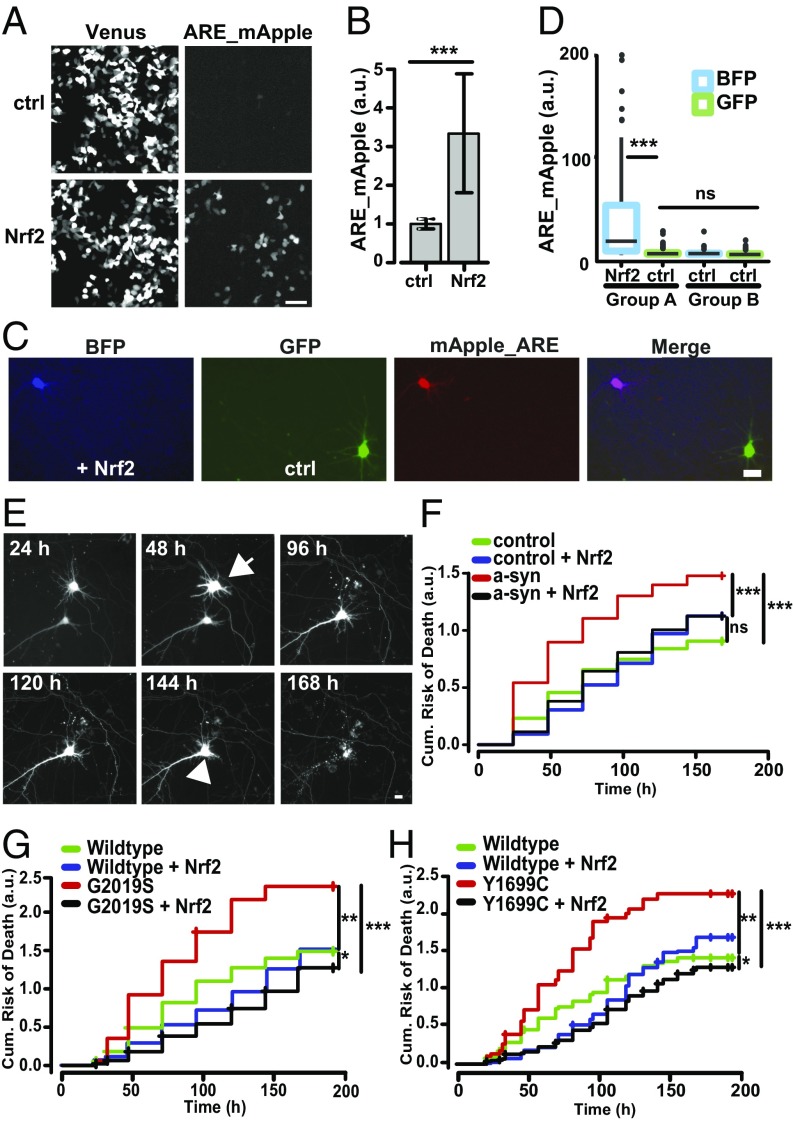

Fig. 1.

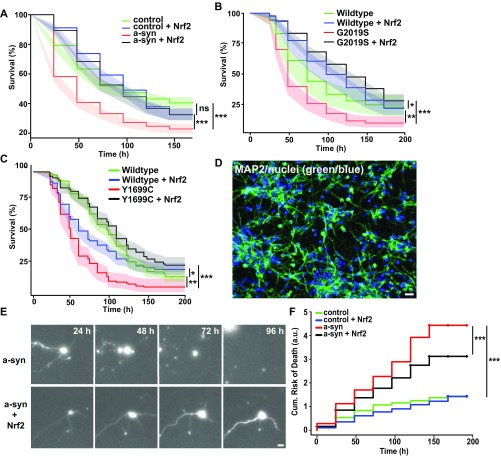

Nrf2 activates ARE-dependent transcription in neurons and blocks degeneration caused by α-synuclein and mutant LRRK2. (A) HEK293 cells cotransfected with Venus and ARE-Apple. (Scale bar, 70 μm.) (B) Nrf2 overexpression up-regulated the ARE reporter, as measured by red fluorescence. Number of cells were as follows: control (ctrl) = 1,499; Nrf2 = 1,529. F value = 135.8, df = 1; ***P < 0.0001; 95% confidence intervals (CIs). (C) Neurons were sequentially transfected with pTag_BFP and Nrf2 (BFP, +Nrf2), followed by GFP and control plasmid (GFP, +ctrl). Both cohorts of neurons were also cotransfected with ARE_mApple. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (D) Only neurons overexpressing Nrf2 showed a significant up-regulation of ARE_mApple expression (group A, BFP Nrf2). Neurons with GFP and control plasmid (group A, GFP ctrl) had a similar level of ARE activation as a population of neurons with no ectopic Nrf2 expression (group B). Number of cells were as follows—group A, BFP Nrf2 = 58, GFP ctrl = 137; group B, BFP ctrl = 51, GFP ctrl = 102. F value = 19.66, df = 3; ***P < 0e−10; ns, not significant; 95% CIs. (E) Images of two longitudinally tracked neurons expressing mRFP and α-synuclein. One neuron underwent neurite degeneration at 48–96 h (arrow); the other remains alive up until 144 h (arrow head). (Scale bar, 10 µm.) (F) Cumulative risk-of-death curves demonstrate that Nrf2 significantly reduced toxicity in neurons expressing α-synuclein. Number of neurons in α-synuclein = 640, α-synuclein + Nrf2 = 563, Control = 663, and Control + Nrf2 = 518. ***P < 0e−10; ns, not significant. (G and H) Cumulative risk-of-death curves demonstrate that Nrf2 significantly reduced toxicity in neurons expressing mutant G2019S LRRK2 or Y1699C LRRK2. (G) Number of neurons for wild-type LRRK2 = 97, wild-type LRRK2 + Nrf2 = 165, G2019S LRRK2 = 171, and G2019S LRRK2 + Nrf2 = 319. *P = 0.01, **P = 0.0004, ***P < 0e−10. (H) Number of neurons for wild-type LRRK2 = 366, wild-type LRRK2 + Nrf2 = 304, Y1699C LRRK2 = 139, and Y1699C LRRK2 + Nrf2 = 260. *P = 5.42e−6, **P = 0.00014, ***P < 0e−14.

We then validated the ARE reporter in primary rat neurons, by first testing if we could activate endogenous Nrf2. Primary rat neurons were cotransfected with Venus and ARE_mApple and treated with tBHQ. At 24 h posttransfection, neurons showed a robust increase in ARE_mApple fluorescence (Fig. S1B). Next, we tested if Nrf2 overexpression could lead to ARE activation in neurons. As primary rat cultures contain some glia, Nrf2 activation in neurons might be caused by glia through a non–cell-autonomous mechanism. To determine the contribution of this mechanism, we labeled two cohorts of neurons in the same cultures with distinct fluorescent labels, pTag-BFP and GFP, via sequential transfections (Fig. 1C). The BFP-labeled cohort was also cotransfected with Nrf2, whereas GFP-labeled neurons were not. Both cohorts of neurons were also transfected with ARE_mApple to report Nrf2-dependent ARE activation. Similar to HEK293 cells, we found that neurons cotransfected with ARE_mApple, Nrf2, and pTag-BFP showed an up-regulation of ARE_mApple fluorescence (Fig. 1D). If glia were driving Nrf2-dependent ARE transcription in neurons, neurons ectopically expressing GFP but not Nrf2 should show an increase in ARE_mApple expression. However, we found that this cohort of neurons had a similar level of ARE activation as a population of neurons with no ectopic Nrf2 expressed in any of the cells. Interestingly, Nrf2 induced a 12.1-fold induction of ARE transcription in neurons, compared with only a 3.3-fold induction in HEK293 cells, suggesting potential differences in basal levels of Nrf2 in neurons and other cells types.

To test Nrf2’s cell-autonomous role in neurons, we measured the expression of known Nrf2 targets, including those involved in stress response and protein homeostasis in neurons transfected with Nrf2. Primary rat cortical neurons were cotransfected with mApple and Nrf2 or control plasmid and fixed 24 h later. Nrf2 overexpression caused a significant increase in expression of proteasome 20s alpha and GST (Fig. S2 A–D), known Nrf2 transcriptional targets (27). After validating Nrf2-dependent activation in neurons, we tested if overexpression of Nrf2 reduced toxicity induced by the PD-associated proteins LRRK2 and α-synuclein in neurons. We examined Nrf2’s effect on toxicity caused by two LRRK2 mutations: the most common PD-associated mutation, G2019S (28), and Y1699C. We showed that both mutations cause dose-dependent toxicity, neurite degeneration, and IB formation (5). To test Nrf2’s effect on α-synuclein–induced toxicity, the wild-type α-synuclein protein was overexpressed. We found that overexpression of α-synuclein in neurons leads to dose-dependent toxicity (29), which models the duplication and triplication mutations of the α-synuclein gene that cause a severe, highly penetrant form of PD (30, 31).

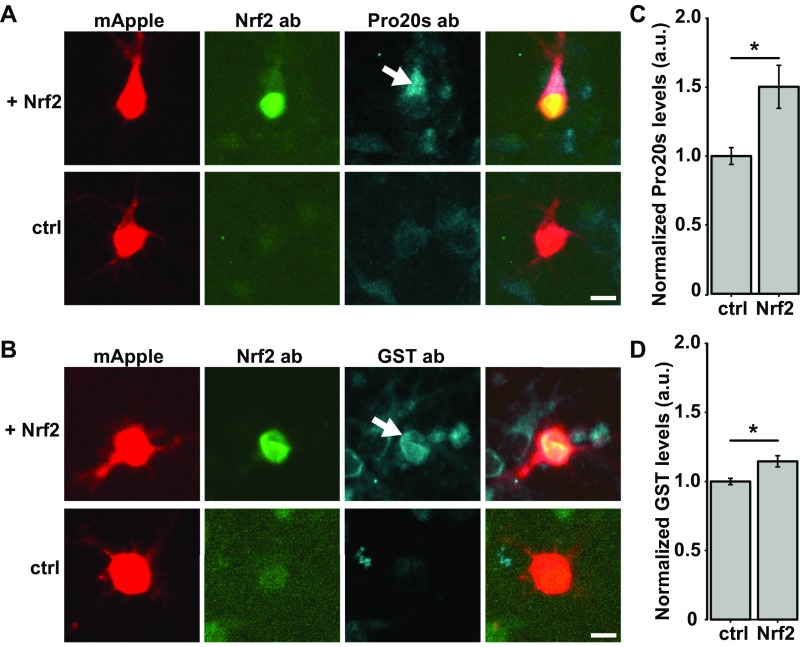

Fig. S2.

(A and B) Primary rodent neurons were cotransfected with mApple and either Nrf2 or control plasmid, fixed 24 h posttransfection, and stained for proteasome 20s alpha (Pro20s) and GST (GST). Neurons transfected with Nrf2 expressed Pro20s and GST at significantly higher levels (arrows). (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (C and D) Fold increase is normalized to the mean of the control at 24 h posttransfection, ± 95% CIs. For Pro20s, the number of cells for control = 23 and Nrf2 = 22; t = –2.77; *P = 0.01. For GST, the number of cells for control = 22 and Nrf2 = 17; t = –2.61; *P = 0.015.

α-Synuclein was cotransfected into primary rat neurons, along with Nrf2 and the morphology marker monomeric red fluorescent protein (mRFP). To ensure that the total DNA transfected into the neurons was the same across conditions, additional control plasmid was transfected into the cohort of neurons without exogenous Nrf2. Approximately 24 h after transfection, a robotic microscope (21) was used to collect consecutive images of the same fluorescent neurons. This approach enabled hundreds of neurons expressing mRFP, Nrf2, and α-synuclein to be longitudinally followed individually, which we did every day for 1 wk. The reproducible temporal expression profile of mRFP (Fig. S3) made it suitable to track neuron morphology (Fig. 1E). As shown in previous studies (21, 22), the loss of the mRFP signal coincided with the loss of membrane integrity (Fig. S4), indicating the time of death for each neuron. Similarly, we cotransfected primary rat neurons with Nrf2-, mRFP-, and either Venus-tagged mutant Y1669C, G2019S, or wild-type LRRK2 (Venus-LRRK2) and longitudinally imaged the cells once a day for 7 d and used the mRFP signal to determine the time of death of each neuron. Additional control plasmid was transfected into the cohort of neurons without exogenous Nrf2 to balance the DNA transfected into the neurons.

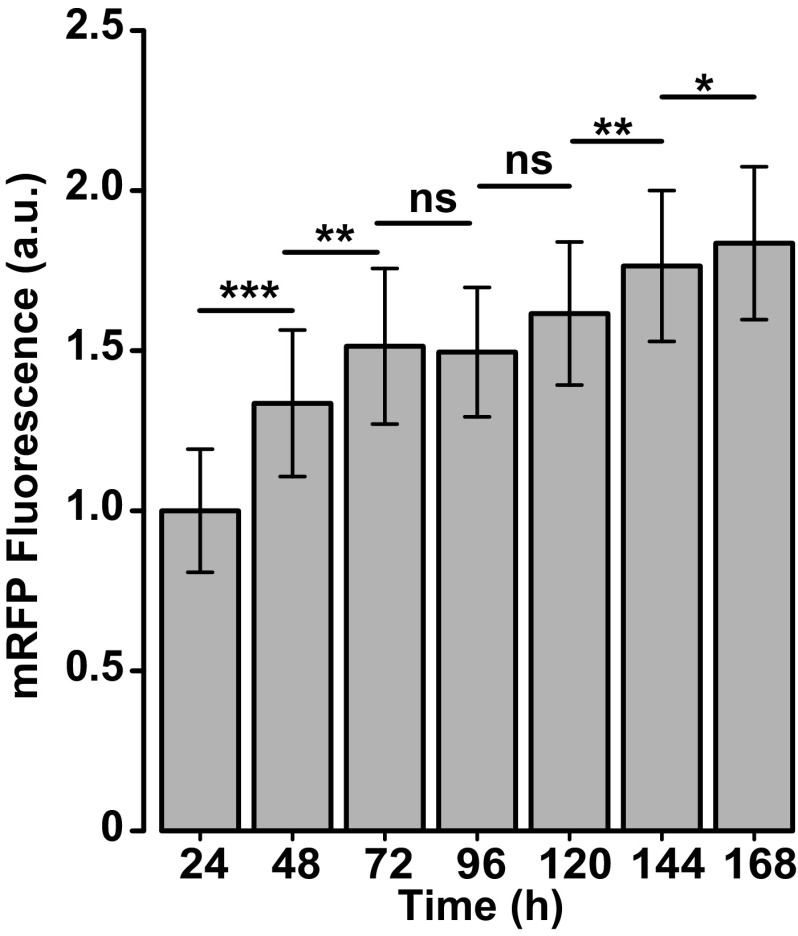

Fig. S3.

Primary neurons transfected with mRFP were followed for 7 d using longitudinal imaging. The mRFP signal steadily increases in a population of neurons over the course of the experiment. Time-specific fluorescence changes in neurons were statistically tested with the generalized estimating equations using the geese function in the geepack R package. Differences in mean fluorescence at select time points were tested using the contrast function in the contrast R package. P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Holm correction method. Number of neurons at 24 h = 523. *P = 8.1e−4, **P < 1.8e−5, ***P < 0e−14; ns, nonsignificant.

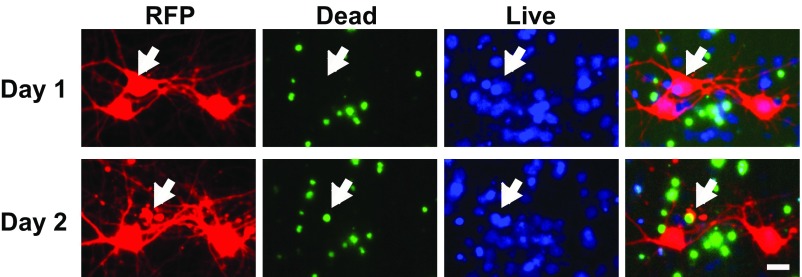

Fig. S4.

Loss of red fluorescent signal corresponds with cell death. Primary neurons were transfected with an RFP and treated with a live dead stain (ReadyProbes Cell Viability, ThermoFisher) 72 h later. The “live” blue stain indicates the health of the cell on day 1. In contrast, the loss of the red fluorescence signal is associated with the appearance of a green “dead” stain on day 2. (Scale bar, 10 μm.)

Using statistical survival tools that are commonly used in clinical studies (24), the time of death of each neuron within the different cohorts being followed was used to generate cumulative survival and risk-of-death curves. These plots revealed that neurons expressing α-synuclein had a greater cumulative risk-of-death and, thus, higher toxicity than control neurons (Fig. 1F and Fig. S5A) and that neurons overexpressing mutant LRRK2 had a greater risk of death than either control neurons or neurons expressing wild-type LRRK2 (Fig. 1 G and H and Fig. S5 B and C). Exogenous overexpression of Nrf2 caused a highly significant reduction in toxicity in neurons expressing either α-synuclein or mutant LRRK2 (Fig. 1 F–H and Fig. S5 A–C). Nrf2 also caused a small but statistically significant increase in survival of neurons overexpressing wild-type LRRK2 (Fig. 1 G and H and Fig. S5 B and C). However, Nrf2 does not seem to cause any dramatic improvement in baseline neuron viability, as Nrf2 did not improve the survival of control neurons (Fig. 1F). For Nrf2 to be considered as a potential therapeutic target, evidence that Nrf2 mitigates neurodegeneration in human neuron models is critical. Human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived from a healthy control individual were differentiated into human neurons (Fig. S5D). iPSC-derived human neurons were cotransfected with a panneuronal GFP_synapsin survival marker, α-synuclein, and either Nrf2 or control plasmid and longitudinally imaged for 7–9 d (Fig. S5E). Neurons expressing exogenous α-synuclein had a greater risk of death than control neurons. Nrf2 reduced the risk of death of neurons exogenously expressing α-synuclein without affecting the survival of control neurons (Fig. S5F). Our results highlight the specificity of Nrf2’s protective effect on neurons undergoing neurodegeneration induced by PD-associated proteins. Furthermore, we show that Nrf2 can act directly in neurons and does not require a non–cell-autonomous mechanism of action.

Fig. S5.

Kaplan–Meier survival functions with 95% CIs for survival at any particular time point demonstrate that overexpressing Nrf2 significantly reduced toxicity in neurons expressing mutant (A) α-synuclein, (B) Venus-G2019S-LRRK2, or (C) Venus-Y1699C-LRRK2. Number of neurons and P values are the same as those described in Fig. 1 F–H. (D) Representative image from immunocytochemistry of human neurons differentiated from iPSCs from a control individual, costained with MAP2 and DAPI. Approximately 75% of cells are MAP2-positive. (Scale bar, 40 µm.) (E) Longitudinal imaging of human neurons expressing GFP_synapsin and α-synuclein and either Nrf2 or control plasmid. The neuron in the Top panels dies between 24 and 48 h, whereas the neuron in the Bottom panels expresses Nrf2 and lives to at least 96 h. (Scale bar, 10 µm.) (F) Cumulative risk of death curves demonstrate that Nrf2 significantly reduced toxicity in neurons expressing mutant α-synuclein. Number of neurons for control = 188, control + Nrf2 = 201, α-synuclein = 252, and α-synuclein + Nrf2 = 280. **P = 0.00071, ***P = 1.11e−16; ns, nonsignificant.

The Protective Effect of Nrf2 Is Time-Dependent.

Although we saw a strong protective effect of Nrf2 on PD-associated protein toxicity, we did observe that the cumulative risk-of-death curves of cells with or without Nrf2 expression diverged to a greater extent at the beginning of the experiment than at later times, hinting that Nrf2’s effects might vary with time. We used Cox proportional hazard (CPH) analysis, a popular survival analysis method (32), to quantify both the magnitude of Nrf2’s effect on toxicity and any adaptive changes in Nrf2’s efficacy over time. The magnitude of Nrf2’s effect on α-synuclein and mutant LRRK2-induced toxicity was surprisingly large (Table S1). Exogenous Nrf2 expression reduced the risk of death by 92% [hazard ratio (HR) of 0.082, P = 5.6e−14] and 86% (HR of 0.142, P = 1.2e−7) in neurons expressing G2019S and Y1699C LRRK2, respectively. Although, in neurons expressing α-synuclein, Nrf2 reduced the risk of death by 67% (HR = 0.33, P < 2e−16). Furthermore, Nrf2’s impact on PD-associated toxicity was most significant early on in the experiment and attenuated significantly with time (Table S1).

Table S1.

CPH analysis of the time-dependent effects of Nrf2 on PD-associated toxicity

| Group | Covariates | HR | 95% CI | P value |

| G2019S LRRK2 | Nrf2 | 0.082 | 0.0447–0.15 | 5.6e–16 |

| Time | 1.454 | 1.2577–1.68 | 4.1e–7 | |

| Y1699C LRRK2 | Nrf2 | 0.1419 | 0.0689–0.292 | 1.2e–7 |

| Time | 1.2661 | 1.0412–1.54 | 1.8e–2 | |

| α-synuclein | Nrf2 | 0.327 | 0.256–0.419 | <2e–16 |

| Time | 3.197 | 2.445–4.181 | <2e–16 | |

| Control | Nrf2 | 0.427 | 0.32–0.568 | 4.6e–10 |

| Time | 2.92 | 2.23–3.82 | 6.6e–15 |

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

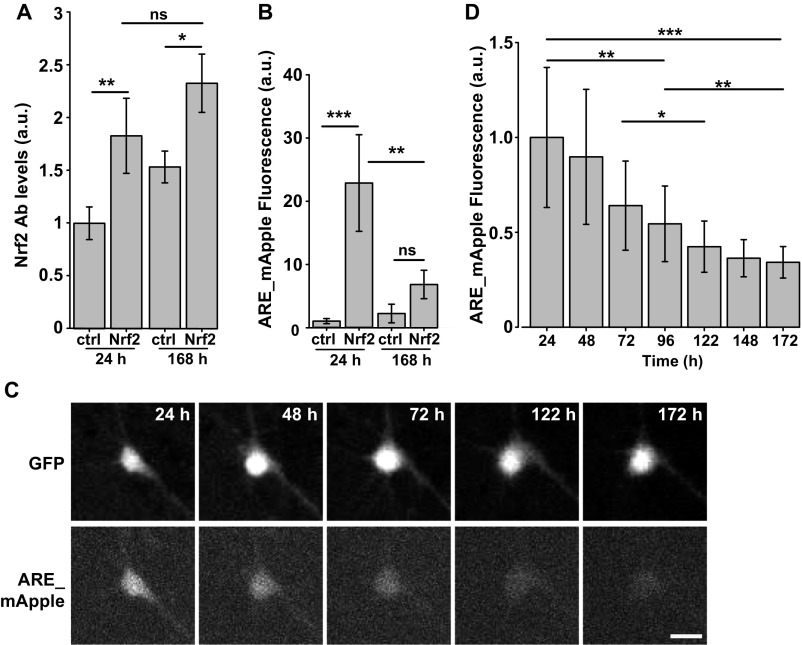

To determine if the time-dependent effect of Nrf2 was due to a decline in Nrf2 levels, we fixed cohorts of Nrf2 transfected neurons at 24 and 168 h posttransfection and measured levels of Nrf2 by immunocytochemistry. Nrf2 levels were comparable across both cohorts of neurons (Fig. S6A). Next, we investigated if the drop in efficacy could be due to a decrease in Nrf2-dependent ARE transcription. Neurons transfected with ARE_mApple were imaged and analyzed for ARE_mApple fluorescence at 24 and 168 h posttransfection. Interestingly, we found that levels of ARE_mApple were significantly lower at 168 h (Fig. S6B). To control for the confound that a decline in Nrf2-dependent ARE transcription could be due to the early death of neurons expressing high levels of ARE_mApple, neurons were cotransfected with ARE_mApple and GFP and longitudinally imaged for a week. The cotransfected GFP was used as a morphology marker to select only neurons that lived up to 172 h posttransfection (Fig. S6C). Neurons showed a significant decrease in ARE_mApple signal with time (Fig. S6 C and D), confirming a decrease in Nrf2-dependent ARE activation in neurons over time, despite a high level of Nrf2 expression. This suggests that neurons are undergoing an adaptive response to Nrf2 that eventually limits its signaling.

Fig. S6.

(A) Primary rodent neurons cotransfected with GFP and either Nrf2 or control plasmid showed no significant difference in Nrf2 levels at 24 or 168 h posttransfection after fixing and staining for Nrf2. Fold increase is normalized to control at 24 h posttransfection. Mean ± 95% CIs. Number of cells in each group was between 30 and 49; F value = 7.753, df = 3. *P = 0.01, **P = 0.03; ns, not significant. (B) Primary rodent neurons cotransfected with GFP, ARE_mApple, and either Nrf2 or control plasmid showed a significant difference in ARE_mApple fluorescence in neurons at 24 or 168 h posttransfection. Fold increase is normalized to control at 24 h posttransfection. Mean ± 95% CIs. Number of cells in each group was between 30 and 53; F value = 10.76, df = 3. **P = 0.006, ***P < 6.1e−6; ns, not significant. (C) Representative images of primary rodent neurons cotransfected with GFP, ARE_mApple, and either Nrf2 or control plasmid and imaged for 7 d. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (D) Neurons that lived up to 7 d were measured for ARE_mApple fluorescence on each day and showed a time-dependent decrease in ARE_mApple fluorescence. Fold increase is normalized to control at 24 h posttransfection. Mean ± 95% CIs. Time-specific fluorescence changes in neurons were statistically tested with the generalized estimating equations using the geese function in the geepack R package. Differences in mean fluorescence at select time points were tested using the contrast function in the contrast R package. P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Holm correction method. Number of cells was 63. *P = 0.0021, **P < 1.2e−4, ***P = 3.3e−7.

Nrf2 Increases α-Synuclein Turnover.

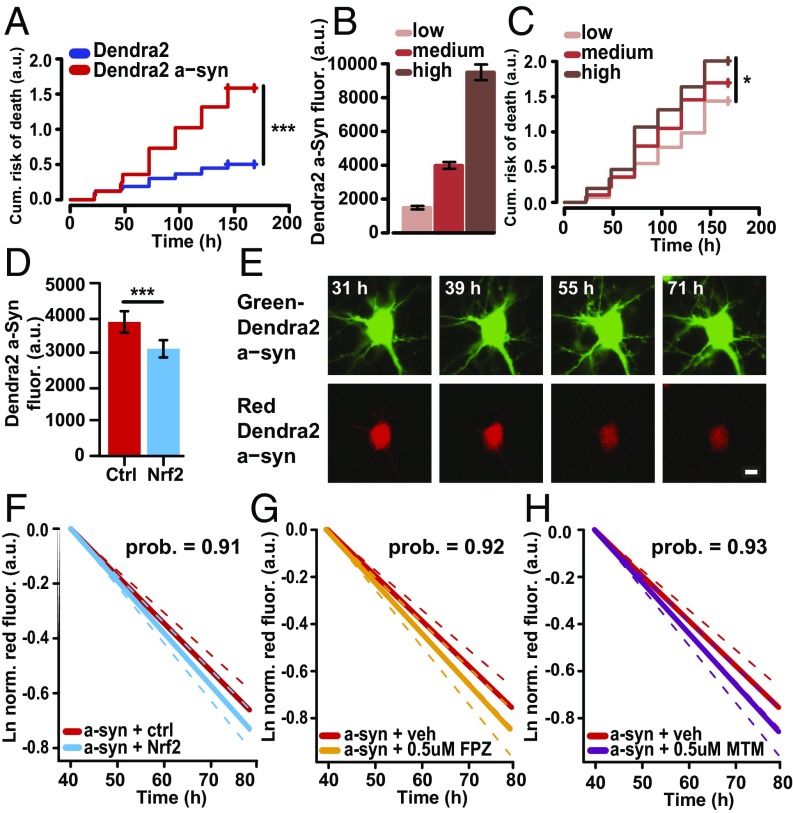

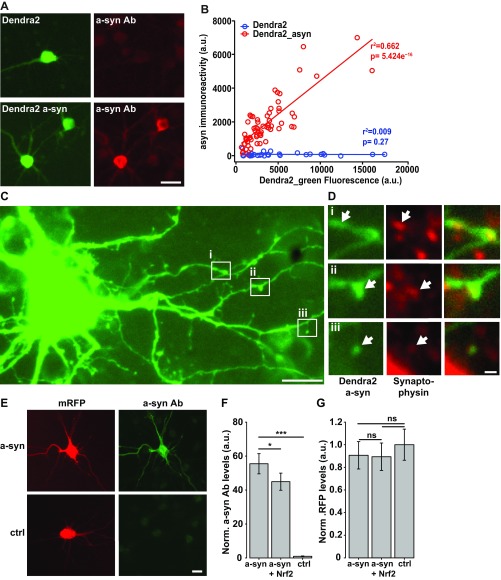

As Nrf2 has been implicated in the up-regulation of targets involved in proteostasis, including molecular chaperones and protein degradation machinery (14, 15, 33–35), we next determined if Nrf2 mediated its strong protective effect on PD-associated protein toxicity in neurons by modulating α-synuclein and LRRK2 dynamics. With α-synuclein’s propensity to misfold and induce a dose-dependent toxicity (29), Nrf2 may reduce α-synuclein toxicity by up-regulating protein degradation machinery to decrease α-synuclein levels (16). To measure the levels of diffuse α-synuclein in single cells, we tagged Dendra2 to α-synuclein and first confirmed that this fusion protein retained the dose-dependent toxicity (Fig. 2 A–C) that we previously showed for untagged α-synuclein (29). Although Dendra2–α-synuclein expression varied significantly from cell to cell, α-synuclein levels in single neurons measured by Dendra2_GFP fluorescence and by immunocytochemistry were highly correlated (Fig. S7 A and B), indicating that Dendra2 fluorescence provided a faithful estimate of the amount of protein in each cell. We also confirmed that Dendra2–α-synuclein was distributed throughout the cytosol, including expression in dendrites and spines of mature neurons (Fig. S7 C and D). We then transfected neurons with Dendra2–α-synuclein and Nrf2 or equal amounts of vector control. We found that cells expressing Nrf2 had lower steady-state levels of Dendra2–α-synuclein (Fig. 2D). We also measured Nrf2’s effect on steady-state levels of untagged α-synuclein. Neurons cotransfected with untagged α-synuclein, mApple, and either Nrf2 or control were fixed at 24 h posttransfection and stained for α-synuclein. Similar to Dendra2–α-synuclein-transfected neurons, α-synuclein levels were lower in neurons transfected with Nrf2. In contrast, levels of cotransfected mApple fluorescence were similar (Fig. S7 E–G), indicating that Nrf2’s effect was specific to α-synuclein and potentially indicating a role for Nrf2 in modulating α-synuclein turnover.

Fig. 2.

Nrf2 decreases α-synuclein levels by increasing its degradation. (A) Overexpression of Dendra2–α-synuclein in neurons leads to an increased risk of death. Number of neurons: Dendra2 = 238, Dendra2–α-synuclein = 239; HR, 2.86; ***P < 0.0001. (B) Neurons expressing Dendra2–α-synuclein were separated into low-, medium-, or high-expressing neurons. (C) Neurons in the highest tercile of Dendra2–α-synuclein expression displayed higher risk of death than neurons in the lowest tercile of Dendra2–α-synuclein expression. Number of neurons in low = 59, medium = 60, and high = 67; HR, 1.54; low versus high *P = 0.03. (D) Steady-state levels of α-synuclein are lower in neurons expressing Nrf2. Number of neurons for ctrl = 139, Nrf2 = 96; t test, F value = 16.01; ***P < 0.0001. (E) A neuron transfected with Dendra2–α-synuclein was pulsed for 1–2 s with 405-nm light and imaged for several days. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (F) Neurons expressing Nrf2 had a 10% increase in Dendra2–α-synuclein degradation. The mean slopes were –0.019 (95% CI –0.021, –0.017) and –0.0173 (95% CI, –0.019, –0.015) for Nrf2 and control cells, respectively. The posterior probability for a steeper mean slope of RFP fluorescence in Nrf2 cells was 0.91, indicating that it is overwhelmingly likely that the degradation of Dendra2–α-synuclein was faster in cells with Nrf2. Number of neurons, Dendra2–α-synuclein/Ctrl = 400 and Dendra2–α-synuclein/Nrf2 = 377. (G and H) Neurons transfected with Dendra2–α-synuclein and exposed to 0.5 µM fluphenazine (FPZ) or 0.5 µM methotrimeprazine (MTM) show a 24% (posterior probability, 0.92) and 23% (posterior probability, 0.93) faster degradation of α-synuclein, respectively, compared with vehicle control (DMSO). The mean slopes for RFP fluorescence were –0.0192 (CI, –0.021, –0.017), –0.0216 (CI, –0.024 to 0.019), and –0.0218 (CI, –0.024 to 0.019) for neurons treated with vehicle (veh), 0.5 µM FPZ, and 0.5 µM MTM, respectively. Number of neurons in veh = 490, FPZ = 337, and MTM = 340.

Fig. S7.

(A) Primary rodent neurons transfected with Dendra2–α-synuclein or Dendra2 were fixed 48 h after transfection and immunostained with antibodies against α-synuclein. (Scale bar, 20 μm.) (B) Neuron-by-neuron comparison of α-synuclein levels, estimated by measuring Dendra2_GFP fluorescence directly and by measuring immunoreactivity against α-synuclein. Measurements of α-synuclein from neurons transfected with the Dendra2–α-synuclein fusion protein are highly correlated to the fluorescence of the Dendra2 tag. The immunoreactivity is specific to α-synuclein because there is no significant immunoreactivity in neurons transfected with Dendra2 alone. (C and D) Primary rodent neurons were cotransfected with Dendra2–α-synuclein at 11 DIV and fixed 48 h posttransfection and stained with a synaptophysin antibody. Dendra2–α-synuclein is expressed throughout the cell body and the neuritic arbor of the neuron including to (D) synaptophysin positive puncta (arrows). [Scale bars, (C) 10 μm and (D) 1 μm.] (E) Primary rodent neurons cotransfected with mRFP, α-synuclein, and either Nrf2 or control plasmid were fixed 24 h posttransfection and immunostained with α-synuclein. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (F) Levels of α-synuclein fluorescence were significantly lower in neurons transfected with Nrf2 compared with control. Fold increase is normalized to control mean ± 95% CIs. Number of cells in each group was between 47 and 111; F value = 173.4, df = 2. *P = 0.015, ***P < 0e−7. (G) Levels of red fluorescence were similar in neurons transfected with Nrf2 or control. Fold increase is normalized to the mean of the control at 24 h posttransfection ± 95% CIs. Number of cells in each group was between 47 and 111; F value = 0.653, df = 3. ns, not significant.

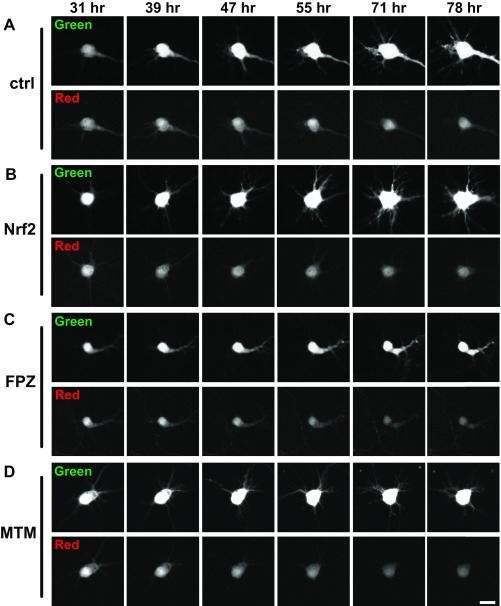

Steady-state levels of α-synuclein result from a balance of production and degradation. As our synuclein expression constructs are not expected to be activated by Nrf2 because they evidently lack AREs, we hypothesized that Nrf2 lowers steady-state synuclein levels by accelerating its degradation. We measured α-synuclein degradation rates in individual neurons by optical pulse labeling (16, 36). This approach takes advantage of the photoswitchable properties of Dendra2 in which an irreversible change of its spectral properties occurs after illumination with short-wavelength light. In our model, cells expressing Dendra2–α-synuclein initially fluoresce green. Upon photoswitching, a population of the green fluorescent protein is irreversibly switched to red, creating a distinct intracellular population of photoconverted α-synuclein that can be followed by the automated longitudinal analysis (Fig. 2E and Fig. S8A). Red fluorescence of Dendra2–α-synuclein was measured longitudinally within individual cells. Using a Bayesian hierarchical model, measurements from hundreds of cells were used to model the underlying degradation of α-synuclein in the population, enabling us to determine if the presence of Nrf2 modulated α-synuclein degradation in single cells. In cells overexpressing Nrf2, the degradation of α-synuclein was 10% faster (posterior probability, 0.92) (Fig. 2F and Fig. S8B). As a comparison, we exposed primary rat neurons expressing α-synuclein to a novel family of small-molecule autophagy inducers, namely FPZ and MTM, which we previously showed to up-regulate autophagy in primary rat cortical neurons (36). FPZ and MTM led to a 24% (posterior probability, 0.92) and 23% (posterior probability, 0.93) faster degradation of α-synuclein, respectively (Fig. 2 G and H and Fig. S8 C and D). We next asked if the benefits of Nrf2 might be explained through its effects on α-synuclein levels. Using CPH analysis, we compared the beneficial effect of Nrf2 on α-synuclein toxicity before and after adjustment for α-synuclein levels. Before incorporating α-synuclein levels into the model, Nrf2 significantly reduces α-synuclein–induced toxicity; however, once α-synuclein levels are incorporated into the model, this significance drops away (Table S2), indicating the Nrf2’s beneficial effect on α-synuclein toxicity can be explained by its effects on α-synuclein levels.

Fig. S8.

Representative images of automated fluorescence microscopy and optical pulse labeling of primary cortical neurons transfected with Dendra2–α-synuclein. Neurons were cotransfected with (A) control (ctrl), (B) Nrf2, or (C and D) treated with autophagy inducers FPZ or MTM. After a 1–2-s pulse of 405-nm light, a portion of Dendra2–α-synuclein was converted from a green to red fluorescent state, and individual neurons were imaged for several days by longitudinal fluorescence microscopy. (Scale bar, 10 μM.)

Table S2.

CPH analysis of the effects of Nrf2 on survival before and after adjustment for α-synuclein levels

| Model description | Covariates | HR | 95% CI | P value |

| Without correcting for α-synuclein levels | Nrf2 | 0.759 | 0.591–0.973 | 0.03 |

| Correcting for α-synuclein levels | Nrf2 | 0.815 | 0.632–1.051 | 0.115 |

| α-Synuclein levels (a.u.) | 1.185 | 1.089–1.289 | 8.14e–5 |

The number of neurons in α-synuclein = 372 and α-synuclein + Nrf2 = 352. a.u., arbitrary unit; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

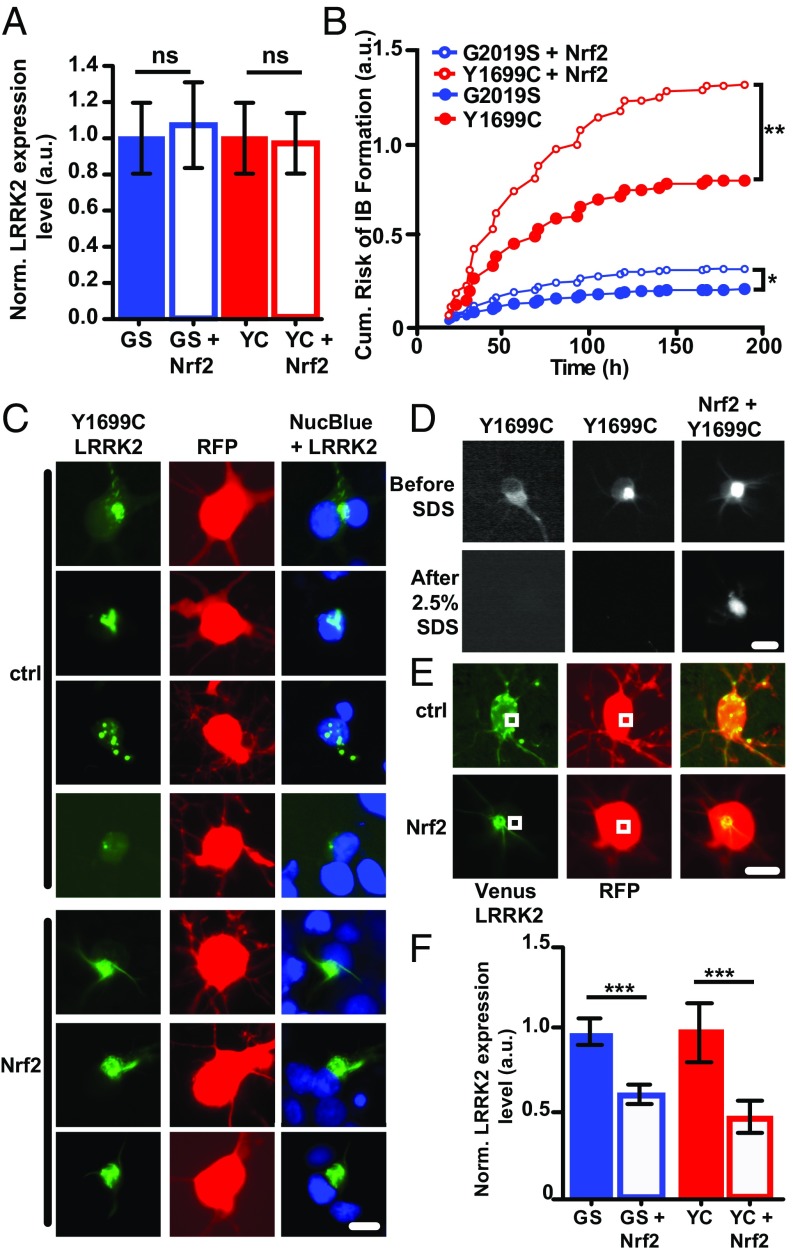

Nrf2 Increases LRRK2 IB Formation and Insolubility.

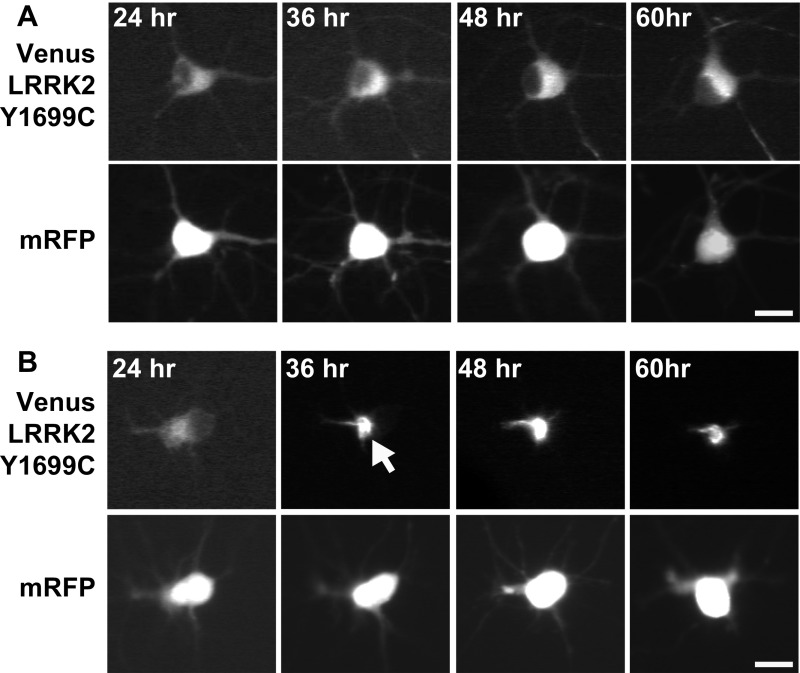

Next, we determined if Nrf2-mediated protection leads to a similar effect on LRRK2 dynamics. We began by looking at steady-state levels of LRRK2, by measuring Venus-LRRK2 levels in neurons cotransfected with mutant Venus-LRRK2 and either Nrf2 or control. In contrast to α-synuclein, Nrf2 did not lead to a detectable decrease in steady-state levels of diffuse mutant LRRK2 at 24 h posttransfection (Fig. 3A). In addition to targeting misfolded proteins for degradation, toxic protein conformers may be sequestered into IBs enabling nonnative toxic epitopes to be buried or refolded (21, 37). Similar to other disease-causing misfolded proteins, LRRK2 has a propensity to aggregate and form IBs (38, 39). Thus, we wanted to determine if the protective effect of Nrf2 is mediated through the shunting of diffuse mutant LRRK2 into IBs, thereby increasing LRRK2 IB formation. To test this, we used our longitudinal imaging platform to track Venus-LRRK2 IB formation in real time. For each neuron expressing mutant Venus-LRRK2, we recorded if and when an IB formed (Fig. S9). As death can preclude IB formation, we plotted the cumulative risk of IB formation, using a semiparametric proportional hazards model that incorporates competing effects, such as death. When we compared the risk of IB formation in neurons expressing mutant Venus-G2019S-LRRK2 or Venus-Y1699C-LRRK2 with and without Nrf2, we found that Nrf2 led to a significantly greater risk of IB formation for the PD-associated LRRK2 mutants (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Nrf2 increases LRRK2 IB formation and insolubility. (A) At 24 h posttransfection, levels of G2019S-LRRK2 and Y1699C-LRRK2 were unchanged in the presence of Nrf2. Number of neurons per group for G2019S (GS) = 200, GS + Nrf2 = 316, Y1699C (YC) = 128, and YC + Nrf2 = 247; 95% CIs. ns, not significant. (B) Nrf2 increases the cumulative risk of IB formation in neurons expressing G2019S-LRRK2 and Y1699C-LRRK2. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.001. (C) Representative images of neurons expressing Y1699C-LRRK2, mRFP, and either Nrf2 or empty vector control at 48–72 h posttransfection. Neurons were treated with NucBlue to label the nuclei. Neurons expressing Nrf2 form more homogeneous, perinuclear, and compact IBs. (Scale bar, 10 µm.) (D) A detergent resistance assay shows that, in the presence of Nrf2, G2019S-LRRK2 IBs are resistant to SDS/Triton X-100 treatment. (Scale bar, 10 µm.) (E) Representative images of neurons cotransfected with Y1699C-LRRK2, RFP, and either Nrf2 or control plasmid at 32–45 h posttransfection. Neurons with IBs were measured for diffuse levels of Venus-LRRK2 elsewhere in the cell (white boxes). (Scale bar, 10 µm.) (F) Neurons that form IBs by 32 h posttransfection in the presence of Nrf2 have significantly lower levels of cytoplasmic diffuse G2019S-LRRK2 and Y1699C-LRRK2 than neurons with no Nrf2. Number of cells per group were GS = 26, GS + Nrf2 = 27, YC = 52, and YC + Nrf2 = 68; 95% CIs; t test; F values 14.93 (G2019S) and 18.08 (Y1699C). ***P = 0.00038 (G2019S) and P = 4.46e−0.5 (Y1699C).

Fig. S9.

Primary rodent neurons were cotransfected with mRFP, Venus-Y1699C-LRRK2, and either Nrf2 or control plasmid and imaged longitudinally. (A) Representative images of a neuron expressing the diffuse form of Venus-Y1699C-LRRK2 at several time points up to 60 h posttransfection. (B) In contrast, representative images of a neuron that is diffuse at 24 h posttransfection but forms a Venus-Y1699C-LRRK2 IB at 36 h posttransfection (arrow). (Scale bar, 10 μm.)

The targeting of IBs to specific cellular locations is considered an additional line of defense in the handling of misfolded proteins (40, 41). In the absence of Nrf2, LRRK2 IBs were more heterogeneous and dispersed throughout the cytoplasm, and the morphology differed from cell to cell (Fig. 3C). However, in the presence of Nrf2, LRRK2 IBs were predominantly restricted to near the nucleus as compact foci (Fig. 3C). The intracellular location of protein IBs is a known predictor of IB insolubility (40). Interestingly, insolubility in high concentrations of detergent is an important characteristic of many protein IBs found in neurodegenerative diseases (42), and in the case of prion disease, insolubility is correlated with slower disease progression (43). Thus, to evaluate the insolubility of LRRK2 IBs, we treated neurons with high concentrations of detergent (2.5% SDS/2.5% Triton-X-100) (44), which revealed that in the presence of Nrf2, LRRK2 IBs were more insoluble than those that formed without Nrf2 (Fig. 3D).

We previously showed that diffuse LRRK2 is toxic in a dose-dependent manner (5), so we hypothesized that Nrf2 may reduce mutant LRRK2-associated toxicity by sequestering misfolded diffuse LRRK2 into more compact IBs. To test this, we measured levels of diffuse LRRK2 in neurons that had formed IBs by 32 h posttransfection (Fig. 3E). We found that, in the presence of Nrf2, neurons with IBs had a significant reduction in diffuse mutant LRRK2 levels elsewhere in the cell (Fig. 3F). These findings indicate that a reduction in PD-associated LRRK2 toxicity by Nrf2 is associated with an augmented risk of IB formation, a reduction in the heterogeneity of IBs, and an increase in IB detergent resistance and improved survival. This suggests that Nrf2 promotes a shift of LRRK2 from the diffuse fraction into IBs and a shift from less ordered IBs to more ordered ones.

Discussion

The prevailing view of Nrf2’s function in the central nervous system is that it acts by a cell-nonautonomous mechanism to activate genes that mitigate reactive oxygen species. However, growing evidence indicates that Nrf2 can act in neurons via a cell-autonomous manner, leading to transcriptional changes in not only oxidative stress-related genes but also those related to proteostasis and specific neuronal functions (45–47). Our work demonstrates that Nrf2 can act in a cell-autonomous manner to potently promote neuronal protein homeostasis and reduce neurodegeneration caused by α-synuclein and mutant LRRK2 expression.

Our study provides supporting evidence for Nrf2’s role in the progression and risk of PD. Genetic association studies linked single nucleotide polymorphisms that lower Nrf2 promoter activity (48) with an increased risk of PD (49). Nrf2 was up-regulated in neurons differentiated from iPSCs derived from PD patients with mutations in Parkin, another PD-associated gene (50). Furthermore, accumulation of Nrf2 and its targets has been observed in surviving dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra of PD patients (51, 52), indicating that the Nrf2 pathway is activated in neurons during the neurodegenerative process. Previous studies in PD models focused on Nrf2’s non–cell-autonomous protective effect on neurons, where expression of Nrf2 in astrocytes reduced neuron death caused by toxins (20) or mutant A53T α-synuclein (53). In contrast to previous studies, we altered expression of Nrf2 directly in primary rat neurons and showed that increased expression of Nrf2 and subsequent activation of ARE transcription was sufficient to activate endogenous stress response mechanisms, leading to improved survival of neurons against toxicity caused by both mutant LRRK2 and α-synuclein.

We also address the effects of chronic activation of Nrf2. Nrf2’s effect on α-synuclein– and LRRK2-induced degeneration attenuated with time and was associated with a time-dependent decrease in Nrf2-dependent transcription, despite a steady level of Nrf2 expression. This suggests that neurons are undergoing an adaptive response to Nrf2 that eventually limits its signaling. Although Nrf2 displays time-dependent effects on PD-associated phenotypes, it does not eliminate the possibility that Nrf2 may be used as a therapeutic strategy in a pulsatile or periodic manner to maximize its benefits and avoid detrimental effects.

Nrf2’s protective effect on neurodegeneration was accompanied by changes in the dynamics of LRRK2 and α-synuclein, strengthening the concept that activation of endogenous defense mechanisms protect against proteostasis stress (54) and could be harnessed for therapeutic intervention. In addition, we support growing evidence that, in addition to antioxidant genes (55), Nrf2 up-regulates genes involved in proteostasis, including components of the proteasome (56, 57) and chaperone systems (15, 27). Interestingly Nrf2’s effect on protein dynamics differed for α-synuclein and LRRK2. Nrf2 accelerates the clearance of α-synuclein, shortening its half-life and leading to lower overall levels of α-synuclein. By contrast, Nrf2 promotes the aggregation of LRRK2 into IBs and promotes the formation of IBs that are more compact and insoluble. How Nrf2 leads to different prominent effects on α-synuclein and LRRK2 dynamics remains unclear. As Nrf2 is activated by a battery of cellular stresses, including perturbations to proteostasis (35), the distinct species of misfolded protein might influence the distinct cellular responses activated by Nrf2. Alternatively Nrf2 may activate the same broad program of gene expression, which includes multiple aspects of protein homeostasis, for both α-synuclein and LRRK2. The differences we observe in terms of Nrf2’s effects on α-synuclein versus LRRK2 might relate to how those two proteins interact with different components of the Nrf2 program. Further investigation of the downstream targets that are activated by Nrf2 during stress-specific degeneration in neurons will provide greater insight into pathways or networks that can be modulated as a therapeutic strategy against PD-associated proteotoxicity.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the S.F. laboratory for useful discussions, G. Howard for editorial assistance, R. Thomas for statistical guidance, and K. Nelson for administrative assistance. The Nrf2 and ARE-Luc plasmids were a gift from Jeffrey Johnson (University of Wisconsin), and α-synuclein plasmid was a gift from Robert Edwards (University of California, San Francisco). S.F. is supported by NIH Grants U54 HG008105, U01 MH1050135, 3R01 NS039074, and R01 NS083390; CIRM Research Grant RB4-06079; the Taube/Koret Center; Michael J. Fox Foundation; and the ALS Association. The Gladstone Institutes received support from National Center for Research Resources Grant RR18928. We thank the Betty Brown Family for their philanthropic support.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Commentary on page 803.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1522872114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Polymeropoulos MH, et al. Mutation in the alpha-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson’s disease. Science. 1997;276(5321):2045–2047. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paisán-Ruíz C, et al. Cloning of the gene containing mutations that cause PARK8-linked Parkinson’s disease. Neuron. 2004;44(4):595–600. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark LN, et al. Frequency of LRRK2 mutations in early- and late-onset Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2006;67(10):1786–1791. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000244345.49809.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spillantini MG, Crowther RA, Jakes R, Hasegawa M, Goedert M. alpha-Synuclein in filamentous inclusions of Lewy bodies from Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(11):6469–6473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skibinski G, Nakamura K, Cookson MR, Finkbeiner S. Mutant LRRK2 toxicity in neurons depends on LRRK2 levels and synuclein but not kinase activity or inclusion bodies. J Neurosci. 2014;34(2):418–433. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2712-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin X, et al. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 regulates the progression of neuropathology induced by Parkinson’s-disease-related mutant alpha-synuclein. Neuron. 2009;64(6):807–827. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orenstein SJ, et al. Interplay of LRRK2 with chaperone-mediated autophagy. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(4):394–406. doi: 10.1038/nn.3350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuanalo-Contreras K, Mukherjee A, Soto C. Role of protein misfolding and proteostasis deficiency in protein misfolding diseases and aging. Int J Cell Biol. 2013;2013:638083. doi: 10.1155/2013/638083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bodner RA, et al. Pharmacological promotion of inclusion formation: A therapeutic approach for Huntington’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(11):4246–4251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511256103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cummings CJ, et al. Over-expression of inducible HSP70 chaperone suppresses neuropathology and improves motor function in SCA1 mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10(14):1511–1518. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.14.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayes JD, McMahon M. NRF2 and KEAP1 mutations: Permanent activation of an adaptive response in cancer. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34(4):176–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lastres-Becker I, et al. α-Synuclein expression and Nrf2 deficiency cooperate to aggravate protein aggregation, neuronal death and inflammation in early-stage Parkinson’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(14):3173–3192. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishii T, et al. Transcription factor Nrf2 coordinately regulates a group of oxidative stress-inducible genes in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(21):16023–16029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.21.16023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu R, et al. Gene expression profiles induced by cancer chemopreventive isothiocyanate sulforaphane in the liver of C57BL/6J mice and C57BL/6J/Nrf2 (-/-) mice. Cancer Lett. 2006;243(2):170–192. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwak MK, et al. Modulation of gene expression by cancer chemopreventive dithiolethiones through the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Identification of novel gene clusters for cell survival. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(10):8135–8145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211898200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsvetkov AS, et al. Proteostasis of polyglutamine varies among neurons and predicts neurodegeneration. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9(9):586–592. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gan L, Johnson JA. Oxidative damage and the Nrf2-ARE pathway in neurodegenerative diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842(8):1208–1218. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson JA, et al. The Nrf2-ARE pathway: An indicator and modulator of oxidative stress in neurodegeneration. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1147:61–69. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siebert A, Desai V, Chandrasekaran K, Fiskum G, Jafri MS. Nrf2 activators provide neuroprotection against 6-hydroxydopamine toxicity in rat organotypic nigrostriatal cocultures. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87(7):1659–1669. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen PC, et al. Nrf2-mediated neuroprotection in the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease: Critical role for the astrocyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(8):2933–2938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813361106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arrasate M, Mitra S, Schweitzer ES, Segal MR, Finkbeiner S. Inclusion body formation reduces levels of mutant huntingtin and the risk of neuronal death. Nature. 2004;431(7010):805–810. doi: 10.1038/nature02998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arrasate M, Finkbeiner S. Automated microscope system for determining factors that predict neuronal fate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(10):3840–3845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409777102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daub A, Sharma P, Finkbeiner S. High-content screening of primary neurons: Ready for prime time. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19(5):537–543. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jager KJ, van Dijk PC, Zoccali C, Dekker FW. The analysis of survival data: The Kaplan-Meier method. Kidney Int. 2008;74(5):560–565. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kraft AD, Johnson DA, Johnson JA. Nuclear factor E2-related factor 2-dependent antioxidant response element activation by tert-butylhydroquinone and sulforaphane occurring preferentially in astrocytes conditions neurons against oxidative insult. J Neurosci. 2004;24(5):1101–1112. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3817-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zagorski JW, et al. The Nrf2 activator, tBHQ, differentially affects early events following stimulation of Jurkat cells. Toxicol Sci. 2013;136(1):63–71. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwak MK, Wakabayashi N, Greenlaw JL, Yamamoto M, Kensler TW. Antioxidants enhance mammalian proteasome expression through the Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(23):8786–8794. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8786-8794.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kay DM, et al. Parkinson’s disease and LRRK2: Frequency of a common mutation in U.S. movement disorder clinics. Mov Disord. 2006;21(4):519–523. doi: 10.1002/mds.20751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakamura K, et al. Direct membrane association drives mitochondrial fission by the Parkinson disease-associated protein alpha-synuclein. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(23):20710–20726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.213538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singleton AB, et al. alpha-Synuclein locus triplication causes Parkinson’s disease. Science. 2003;302(5646):841. doi: 10.1126/science.1090278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ibáñez P, et al. Causal relation between alpha-synuclein gene duplication and familial Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2004;364(9440):1169–1171. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bellera CA, et al. Variables with time-varying effects and the Cox model: Some statistical concepts illustrated with a prognostic factor study in breast cancer. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rangasamy T, et al. Genetic ablation of Nrf2 enhances susceptibility to cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(9):1248–1259. doi: 10.1172/JCI21146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thimmulappa RK, et al. Identification of Nrf2-regulated genes induced by the chemopreventive agent sulforaphane by oligonucleotide microarray. Cancer Res. 2002;62(18):5196–5203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cullinan SB, et al. Nrf2 is a direct PERK substrate and effector of PERK-dependent cell survival. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(20):7198–7209. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.20.7198-7209.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barmada SJ, et al. Autophagy induction enhances TDP43 turnover and survival in neuronal ALS models. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10(8):677–685. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller J, et al. Identifying polyglutamine protein species in situ that best predict neurodegeneration. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7(12):925–934. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greggio E, et al. Kinase activity is required for the toxic effects of mutant LRRK2/dardarin. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;23(2):329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.MacLeod D, et al. The familial Parkinsonism gene LRRK2 regulates neurite process morphology. Neuron. 2006;52(4):587–593. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaganovich D, Kopito R, Frydman J. Misfolded proteins partition between two distinct quality control compartments. Nature. 2008;454(7208):1088–1095. doi: 10.1038/nature07195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tyedmers J, Mogk A, Bukau B. Cellular strategies for controlling protein aggregation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(11):777–788. doi: 10.1038/nrm2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campbell BC, et al. Accumulation of insoluble alpha-synuclein in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurobiol Dis. 2000;7(3):192–200. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Legname G, et al. Continuum of prion protein structures enciphers a multitude of prion isolate-specified phenotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(50):19105–19110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608970103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kazantsev A, Preisinger E, Dranovsky A, Goldgaber D, Housman D. Insoluble detergent-resistant aggregates form between pathological and nonpathological lengths of polyglutamine in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(20):11404–11409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee JM, Shih AY, Murphy TH, Johnson JA. NF-E2-related factor-2 mediates neuroprotection against mitochondrial complex I inhibitors and increased concentrations of intracellular calcium in primary cortical neurons. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(39):37948–37956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305204200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bell KF, et al. Neuronal development is promoted by weakened intrinsic antioxidant defences due to epigenetic repression of Nrf2. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7066. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quinti L, et al. SIRT2- and NRF2-targeting thiazole-containing compound with therapeutic activity in Huntington’s disease models. Cell Chem Biol. 2016;23(7):849–861. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marzec JM, et al. Functional polymorphisms in the transcription factor NRF2 in humans increase the risk of acute lung injury. FASEB J. 2007;21(9):2237–2246. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7759com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.von Otter M, et al. Association of Nrf2-encoding NFE2L2 haplotypes with Parkinson’s disease. BMC Med Genet. 2010;11:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Imaizumi Y, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction associated with increased oxidative stress and α-synuclein accumulation in PARK2 iPSC-derived neurons and postmortem brain tissue. Mol Brain. 2012;5:35. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-5-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramsey CP, et al. Expression of Nrf2 in neurodegenerative diseases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66(1):75–85. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e31802d6da9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Muiswinkel FL, et al. Expression of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase in the normal and Parkinsonian substantia nigra. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25(9):1253–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gan L, Vargas MR, Johnson DA, Johnson JA. Astrocyte-specific overexpression of Nrf2 delays motor pathology and synuclein aggregation throughout the CNS in the alpha-synuclein mutant (A53T) mouse model. J Neurosci. 2012;32(49):17775–17787. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3049-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Calamini B, Morimoto RI. Protein homeostasis as a therapeutic target for diseases of protein conformation. Curr Top Med Chem. 2012;12(22):2623–2640. doi: 10.2174/1568026611212220014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wild AC, Moinova HR, Mulcahy RT. Regulation of gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase subunit gene expression by the transcription factor Nrf2. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(47):33627–33636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pickering AM, Linder RA, Zhang H, Forman HJ, Davies KJ. Nrf2-dependent induction of proteasome and Pa28αβ regulator are required for adaptation to oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(13):10021–10031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.277145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grimberg KB, Beskow A, Lundin D, Davis MM, Young P. Basic leucine zipper protein Cnc-C is a substrate and transcriptional regulator of the Drosophila 26S proteasome. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31(4):897–909. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00799-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.HD iPSC Consortium Induced pluripotent stem cells from patients with Huntington’s disease show CAG-repeat-expansion-associated phenotypes. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11(2):264–278. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Burkhardt MF, et al. A cellular model for sporadic ALS using patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2013;56:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]