Significance

Fluorescence-based optical imaging is an important tool allowing researchers and clinicians to molecularly probe wide-ranging biological structures and processes. To break through the traditional molecular imaging window spanning from the visible to the near-infrared (NIR)-I (400–900 nm) region for imaging multiplicity, newly designed and ultrapurified fluorescent probe-antibody conjugates with fluorescence emissions in the NIR-II region (1,000–1,700 nm) have been developed. These NIR-II probes can reduce background autofluorescence for deep-tissue molecular imaging in a 3D imaging mode. These probes open up more and deeper nonoverlapping molecular imaging channels for complex biological systems.

Keywords: NIR-II molecular imaging, bioconjugate, clickable dye, density gradient ultracentrifugation separation, NIR-II multicolor molecular imaging

Abstract

Fluorescence imaging multiplicity of biological systems is an area of intense focus, currently limited to fluorescence channels in the visible and first near-infrared (NIR-I; ∼700–900 nm) spectral regions. The development of conjugatable fluorophores with longer wavelength emission is highly desired to afford more targeting channels, reduce background autofluorescence, and achieve deeper tissue imaging depths. We have developed NIR-II (1,000–1,700 nm) molecular imaging agents with a bright NIR-II fluorophore through high-efficiency click chemistry to specific molecular antibodies. Relying on buoyant density differences during density gradient ultracentrifugation separations, highly pure NIR-II fluorophore-antibody conjugates emitting ∼1,100 nm were obtained for use as molecular-specific NIR-II probes. This facilitated 3D staining of ∼170-μm histological brain tissues sections on a home-built confocal microscope, demonstrating multicolor molecular imaging across both the NIR-I and NIR-II windows (800–1,700 nm).

For decades, fluorescence-based optical imaging in the visible and near-infrared (NIR) spectra up to ∼900 nm has provided a critical tool for researchers and clinicians to molecularly probe wide-ranging biological processes and disease markers in vitro when examining tissues and cells (1, 2). The study of biological systems often requires the simultaneous observation of several proteins/organs in live cells/body. Although multicolor fluorescence imaging has been achieved using organic dyes or quantum dots in the visible to NIR-I range (400–900 nm) (3, 4), imaging multiplicity is limited by the number of fluorescent channels with nonoverlapping emission (5). Over the past several years, efforts to extend the spectral range of fluorophores into the second NIR optical window (NIR-II; 1,000–1,700 nm) have yielded improved photon penetration depth, minimized scattering, and reduced background autofluorescence compared with the visible or NIR-I (∼750–900 nm) imaging window (6–13). The wide fluorescent window from visible to NIR-II (400–1,700 nm) could greatly increase imaging multiplicity and enhance the capabilities of molecular imaging based on fluorescence techniques.

To date, most NIR-II fluorescence imaging has focused on in vivo visualization of vascular diseases, brain hemodynamics in response to trauma, and tumor detection (14). In vitro molecular imaging of cells and tissues in 2D or 3D space (15–17) could strongly benefit from the broader spectral imaging window extending into NIR-II, adding more colors and increased multiplexing capability, accompanied by the advantages of increased penetration depth and reduced tissue endogenous autofluorescence levels afforded by molecular NIR-II probes (12, 18, 19). The increased photon penetration depth allows for visualization of deeper physiological structures, opening the possibility of layer-by-layer fluorescence imaging for 3D molecular imaging using simple one-photon techniques (9, 20, 21). Furthermore, the low NIR-II tissue autofluorescence that eventually could reach near-zero levels in the NIR-IIb (1,500–1,700 nm) window could facilitate a marked increase in fluorescent probe signal-to-background ratios and imaging specificity for fluorescent probes (22–24).

Thus far, there is a dearth of fluorophores for use in NIR-II relative to the numerous counterparts in the visible and NIR-I region. Existing NIR-II fluorescent agents include various molecular dyes and inorganic semiconducting nanomaterials used mostly as nontargeted fluorophores, with few developed molecular-specific probes emitting >1,000 nm (11, 25). For NIR-II microscopic imaging techniques and the NIR-II field in general to benefit from long-wavelength fluorescent imaging, the development of highly selective NIR-II molecular imaging agents is paramount (26–28). Although some bioconjugation protocols for covalently modifying NIR-II nanomaterials with proteins and antibodies exist (29), the development of high-efficiency conjugation routes for NIR-II fluorophores remains highly desirable. Moreover, existing NIR-II agent/protein conjugates suffer from a difficulty in separating conjugates from both unconjugated proteins and free NIR-II fluorophores (29), The unbound antibodies result in poor molecular sensitivity/specificity, whereas unbound NIR-II fluorophores cause high nonspecific background staining.

We have developed a clickable organic fluorophore and a carbon nanotube fluorescent agent conjugated to molecularly specific proteins or antibodies. The fluorophore and fluorescent agent were purified effectively through density gradient ultracentrifugation (DGU) separations (30), and subjected to multicolor molecular imaging in the 800- to 1,700-nm NIR region of brain tissues using a home-built confocal microscope. We demonstrated the first multicolor biological imaging in the extended 800- to 1,700-nm NIR window in 2D as well as in 3D in a layer-by-layer manner through biological tissues.

Results and Discussion

A Clickable Fluorophore (IR-FGP) with High Quantum Yield in the NIR-II Window.

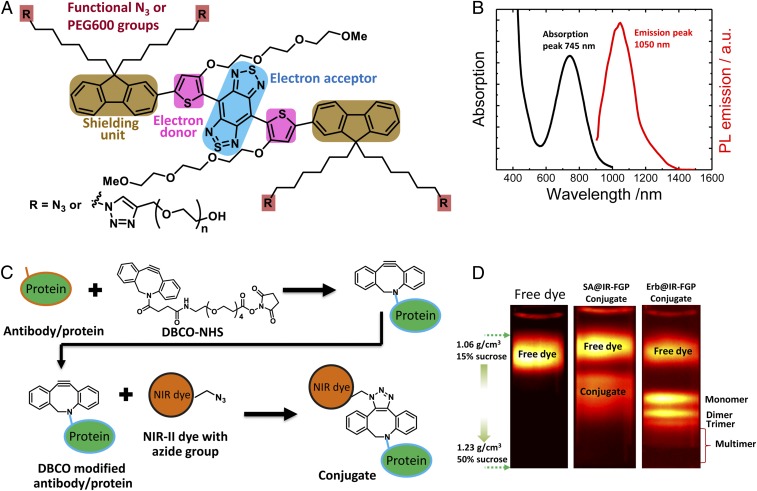

We synthesized the NIR-II fluorophore IR-FGP with bright emission centered at ∼1,050 nm in aqueous solution by systematically tuning a donor–acceptor–donor dye architecture. Benzo[1,2-c:4,5-c′]bis([1,2,5] thiadiazole) (BBTD) served as the acceptor unit, with tert(ethylene glycol) (TEG)-substituted thiophene as the bridging donor unit (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). The TEG substitution on thiophene close to BBTD is vital, because it can distort the conjugated backbone and increase the dihedral angle between BBTD and TEG-thiophene compared with triphenylamine (31), 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene (32), and thiophene (33) donors, affording reduced molecular interactions/aggregation for brighter emission. (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 presents theoretical modeling results.) Meanwhile, the flexible and hydrophilic TEG chain can improve the solubility of the molecular dye compared with the 3,4-ethylenedioxy thiophene donor developed previously (32). Furthermore, dialkyl chain-substituted fluorene units were used as the shielding units, because the stretched dialkyl chains out of the conjugated backbone plane could efficiently prevent parallel intermolecular interactions. The termini of the alkyl chains were modified with azide groups. Two of the termini were functionalized with polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains to enable good aqueous solubility and biocompatibility, and two azide groups were left for further bioconjugation through click chemistry. Synthesis and characterization procedures are detailed in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods, Scheme S1, and Fig. S1.

Fig. 1.

Clickable dye (IR-FGP) with high QY in the NIR-II window used for specific bioconjugation. (A) Chemical structure of IR-FGP with donor–acceptor–donor architecture containing two PEG chains and two azide groups for biocompatibility and bioconjugation. (B) Absorption and photoluminescence (PL) emission (808-nm excitation) spectra of IR-FGP. (C) Scheme of the conjugation route between IR-FGP and proteins by click chemistry. The protein was connected with the DBCO-NHS linker, and then the DBCO-modified protein was reacted with IR-FGP. (D) PL image of post-DGU tubes of free IR-FGP, SA@IR-FGP, and Erb@IR-FGP. The sucrose gradient ranged from 1.06 to 1.23 g/cm3 (15–50 wt%). SI Appendix, Fig. S4 shows a complete density profile along the centrifuge tubes. Images were obtained on a home-built NIR-II set-up with 808 nm excitation (with 850- and 1,000-nm short-pass filters) and 900- and 1,100-nm long-pass emission filters.

The UV-Vis-NIR absorption spectrum of IR-FGP in water exhibited an absorption peak at 745 nm, whereas the fluorescence emission spectrum showed an emission peak centered at 1,050 nm with a signal in the range of 900–1,400 nm under 808-nm laser excitation (Fig. 1B). The quantum yield (QY) of IR-FGP in aqueous solution was 1.9%, the highest among organic NIR-II dyes in aqueous solution reported thus far [808-nm excitation with HiPCO single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) as the reference fluorophore; SI Appendix, Fig. S3A] (31). The enhanced QY of IR-FGP in water resulted from the aforementioned molecular engineering of the TEG-substituted thiophene donor and fluorene shielding groups in the dye structure. It should be pointed out that a NIR-II molecular fluorophore with thiophene and fluorene as the donor was reported previously, and it exhibited high fluorescence QY in toluene (34); however, its analog with ionic groups showed little fluorescence in aqueous solution (QY <0.1%) (33). The molecular fluorophore IR-FTP with TEG-thiophene substituted by thiophene also exhibited a fluorescence QY of only 0.020%, highlighting the novelty of the TEG-thiophene bridge in IR-FGP (SI Appendix, Fig. S3C).

High-Performance Conjugate of IR-FGP Achieved Through Click Chemistry and DGU Purification.

Click chemistry using the azide groups on IR-FGP allowed facile bioconjugation to a variety of proteins and antibodies such as streptavidin (SA), Erbitux, an anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) antibody, and anti-mouse IgG antibodies. The amino groups on proteins were first connected with dibenzocyclooctyne (DBCO)-PEG4-NHS ester to introduce alkyne groups (35). The DBCO-modified protein was then subsequently reacted with the azide-modified IR-FGP to form dye-protein conjugates (Fig. 1C; complete bioconjugation details are provided in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods). The remarkably high efficiency of DBCO click chemistry resulted in nearly complete dye labeling of the protein. Any excess of free dye molecules was removed by an efficient isopycnic DGU separation using the discrepancy in buoyant density between labeled proteins (monomer, dimer, and trimer: 1.11–1.17 g/cm3) and the free dye (1.06–1.09 g/cm3). Once a linear density gradient was established (SI Appendix, Materials and Methods and Fig. S4), ultracentrifugation caused species to migrate to a position within the gradient where their buoyant density matched that of the surrounding gradient. Fig. 1D shows the post-DGU centrifuge tubes of free IR-FGP, SA@IR-FGP, and Erb@IR-FGP conjugates with a free dye band near the top of the centrifuge tube and a labeled protein region near the bottom; SI Appendix, Fig. S4 D and E provides additional details. Interestingly, the Erbitux existing in a monomer, a dimer, a trimer, and a multimer (known to exist in Erbitux) (36) before conjugation were clearly separated in the density gradient, indicating that these separations rival centrifuge filter and dialysis techniques with a known capacity for resolving each species (36). The density gradient separations proved scalable for manufacturing large batches of IR-FGP imaging agents when using production-level rotors with a 50-mL centrifuge tube loading capacity (SI Appendix, Materials and Methods and Fig. S4 F–I).

A Microarray Assay Screening Method Developed to Test the Conjugates.

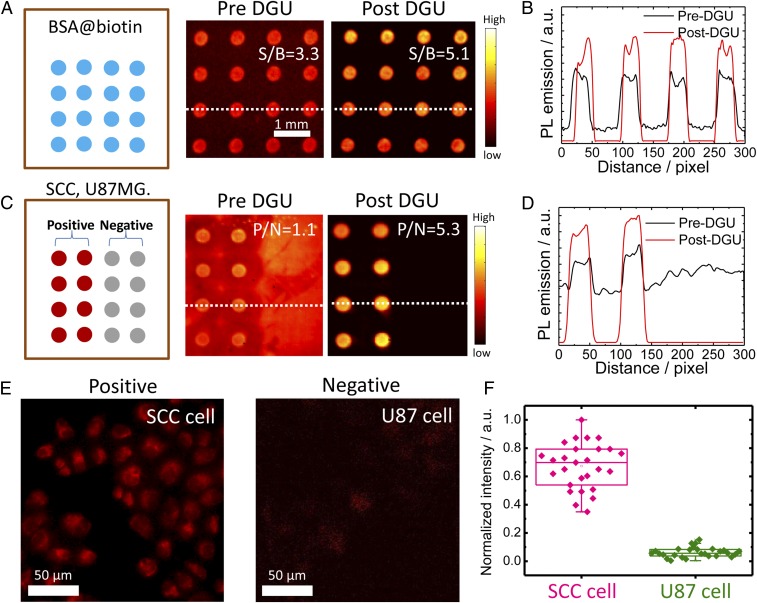

The assay screening method to test the activity of the bioconjugate was developed using printed spots of either BSA-biotin or lysed cells pertaining EGFR biomarkers on a plasmonic fluorescence-enhancing gold slide (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A) (37, 38). Incubation of IR-FGP@protein conjugates followed by washing revealed spots with bright fluorescence emission, demonstrating the molecular selectivity of the NIR-II molecular probes through the selective binding between SA and biotin, or between Erbitux and EGFR (Fig. 2 A and C) (37–39). A fluorescence intensity cross-sectional line profile of the spots for both assays clearly showed a marked increase in the signal-to-background ratio (SBR) after DGU purification (Fig. 2B). The Erb@IR-FGP conjugate demonstrated an increased microarray assay-positive/negative (P/N) ratio (EGFR+ and EGFR-) of 1.1 (pre-DGU) to 5.3 after a DGU separation (Fig. 2D). The enhanced SBR or P/N ratio is due to the removal of free IR-FGP, which could cause nonspecific binding on the slide. Molecular imaging of cells labeled with the Erb@IR-FGP conjugate demonstrated excellent selectivity, with strong fluorescence past 1,100 nm observed from EGFR+ SCC cells and nearly zero fluorescence observed from EGFR- U87MG cells (Fig. 2 E and F). The anti-mouse IgG@IR-FGP was also obtained through a similar conjugation route with high purity for molecular imaging of tissues (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B).

Fig. 2.

The microarray assay screening method developed to test the conjugates. (A) Assay analysis of DGU fraction of SA@IR-FGP. BSA-biotin was printed on the plasmonic fluorescence-enhancing gold slide, after which the pre/post-DGU conjugates were incubated on the slide. Finally, the slide was scanned by a 10× magnification NIR-II setup with 808-nm excitation and a 1,100-nm long-pass emission filter. (B) Cross-sectional intensity profile of the spot signal. (C and D) Assay analysis of the DGU fractions of Erb@IR-FGP. SCC and U87 cell lysates were printed on plasmonic fluorescence-enhancing gold slides for testing the conjugate Erb@IR-FGP. The slide was finally scanned with a 10× magnification NIR-II setup with 808-nm excitation and a 1,100-nm long-pass emission filter. Note that the gold slide has a certain autofluorescence under the testing condition. (E) Targeted cell staining by Erb@IR-FGP (SCC and U87 cell lines as positive and negative controls) scanned by a home-built microscope with 785-nm excitation and a 1,050-nm long-pass emission filter. (F) PL intensity statistic of SCC and U87 cells.

Development of Molecular Imaging Conjugate in the NIR-IIb Region by SWCNTs.

We also developed an NIR-IIb >1,500-nm–emitting molecular imaging agent based on laser-vaporization SWCNTs enriched in fluorescent, semiconducting SWCNTs. The nanotubes were first coated with amine-terminated polymers (22, 40, 41) and then conjugated to SA before purification via DGU (SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7). The brightest SA@SWCNT fractions were isolated through a DGU exploiting differences in the sedimentation coefficient of SA-labeled SWCNTs vs. free SWCNTs. After collection, fractions were combined with biotinylated antibodies for molecular imaging of specific targets in cells and tissues in the >1,500-nm wavelength range under 808-nm excitation, which afforded a remarkably large Stoke shift.

Multicolor 2D/3D Staining in the NIR-I/II Window (800–1,700 nm).

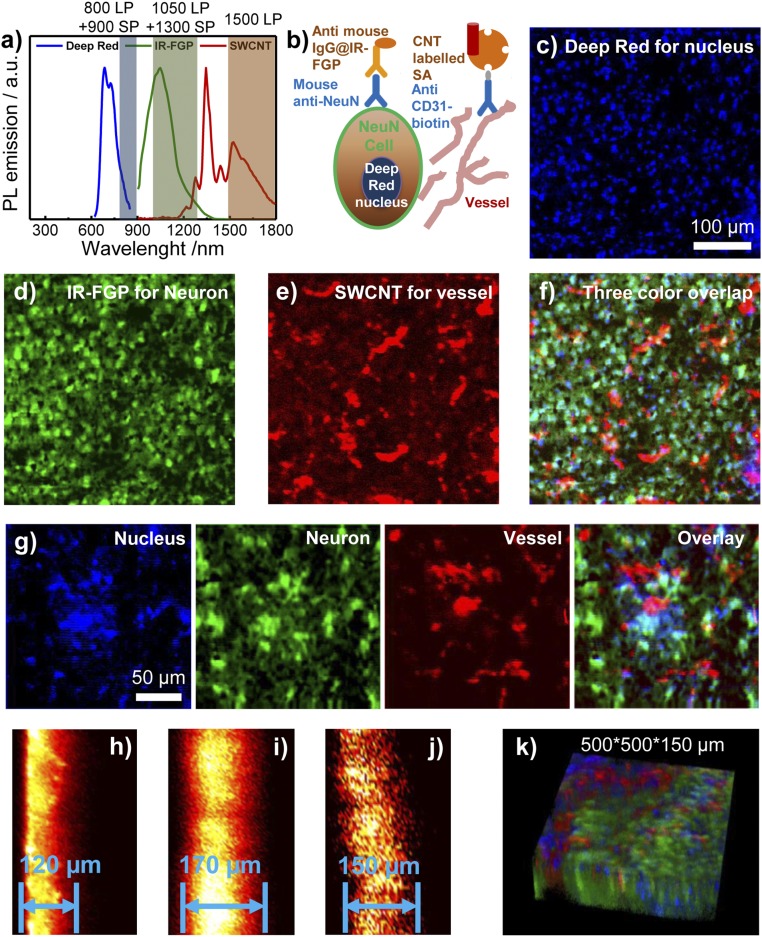

With the newly developed dual NIR-II imaging probes (Erb@IR-FGP emission peak ∼1,050 nm and SWCNT-SA emission at 1,500–1,700 nm) and a commercially available Deep Red NIR-I stain specific to the cell nucleus (emission ∼600–900 nm), fluorescence staining of mouse brain tissue sections enabled multicolor imaging in the NIR-I/II window (range, 800–1,700 nm) (Fig. 3A). An immunohistochemistry molecular staining was performed by incubating tissue sections with a biotinylated anti-CD31 antibody and a mouse anti-neuron primary antibody in 10% (vol/vol) goat serum (for blocking nonspecific interactions). Following the application of primary antibodies, a mixture of molecular probes consisting of SA@SWCNT, anti-mouse IgG@IR-FGP, and the Deep Red nuclear stain simultaneously labeled brain blood vessels (SWCNTs, assigned to a false-color red channel), neurons (IR-FGP; green channel), and nuclei (commercial NIR-I stain; blue channel) (Fig. 3B) (14, 42, 43). Fig. 3 C–F shows the 2D three-color [850–900 nm labels for cell nuclei, 1,050–1,300 nm for neurons (44), and 1,500–1,700 nm for blood vessels] images of each molecular feature in addition to the multicolor overlay. Fig. 3G provides a higher-magnification image, and SI Appendix, Fig. S8 presents more images. Three-color imaging of an SCC tumor was also performed using the NIR-I nuclear stain, Erb@IR-FGP (cell membrane EGFR), and anti-mouse CD31-biotin/SA@SWCNT (vessel) (SI Appendix, Fig. S9A). The present technique can be readily expanded to any other targets of interest by applying the specific antibody or protein conjugation.

Fig. 3.

Multicolor 2D/3D staining in NIR-I and NIR-II windows (800–1,700 nm). (A) PL emission spectra of Deep Red, IR-FGP, and IIb SWCNT including the long-pass/short-pass filter ranges used for three-color imaging. (Although there is slight emission overlay between IR-FGP and SWCNT, the lower QY of SWCNT did not affect the IR-FGP channel.) (B) Scheme of molecular imaging with three color channels. (C–F) 2D multicolor labeling of brain tissue imaged with a home-built confocal system. (C) Deep Red with NIR-I emission for staining the nucleus (658-nm excitation with 850-nm long-pass and 900-nm short-pass emission filters. Note that the 850-nm long-pass filter can be replaced with an 800-nm filter in the present confocal setup to get similar results with higher signal intensities. Images were plotted by ImageJ, increasing the z-scale to eliminate autofluorescence and NSB background signal. SI Appendix, Fig. S8E provides raw data without low z-scale changes. (D) Mouse anti-neuron and anti-mouse IgG@IR-FGP with NIR-IIa emission for staining the neuron (785-nm excitation with 1,050-nm long-pass and 1,300-nm short-pass emission filters). Clear visualization of neuron nucleus with light staining of cell cytoplasm is evident. (E) Anti-CD31 and SA@SWCNT with NIR-IIb emission for staining vessels (785-nm excitation with 1,500-nm long-pass emission filter). (F) Three-color overlapping image of nucleus, neurons, and vessels. (G) Magnified multicolor brain tissue staining with higher resolution. (H–J) Confocal scanning from cross-sections of brain tissue. Scanning depths: Deep Red (H), 120 µm; IR-FGP (I), 170 µm; SWCNT (J), 150 µm. For cross-sectional scanning, the achievable imaging depth was defined as the depth beyond which the measured S/B ratio fell below 2.5. (K) Three-color 3D rendering of nucleus, neuron, and vessel channels obtained with NIR-I/II confocal microscopy. A homebuilt stage scanning confocal setup was used to obtain confocal images. The 100× objective (Olympus, oil immersion, NA 0.8) focuses the excitation laser to a tiny spot with a few μm diameter onto the sample, and the fluorescence goes through 800-nm long-pass dichoric and emission filters to a photomultiplier tube (PMT) detector. A 150-μm pinhole is used to reject out-of-focus signals. For the Deep Red channel, a 658-nm laser was used for excitation, and the signal was detected with a PMT detector (Hamamatsu H7422-50). For the IR-FGP and SWCNT channels, a 785-nm laser was used for excitation, and the signal was detected with an NIR PMT detector (Hamamatsu H12397-75). The scanning rate was 2.5 ms/pixel.

Whereas imaging multiple features demonstrated the selectivity of each molecular probe, we used different NIR-II fluorophores to probe identical physiological structures and examine the SBR as a function of NIR-II imaging wavelength. Applying a mixture of SA@IR-FGP and SA@SWCNT for vessel staining using biotinylated anti-CD31 as the primary antibody, we found that the blood vessel SBR demonstrated a marked increase of 11.3 in NIR-IIb (1,500–1,700 nm) with SWCNTs, compared with a SBR of 5.6 with the shorter emission wavelength IR-FGP probe (1,100–1,300 nm), owing to the ultra-low background autofluorescence afforded by 808-nm excitation with >1,500-nm emission SWCNT NIR-IIb probes (SI Appendix, Fig. S9B).

Finally, we exploited the NIR-II probes for 3D layer-by-layer molecular imaging of tissues using a home-built one-photon confocal imaging system, achieving 3D tomographic imaging with sufficient penetration depths and reducing background autofluorescence levels. A cross-sectional z-scan investigation of the staining depth of the various probes revealed maximum depths of 120 µm with the NIR-I nuclear stain, 170 µm with the IR-FGP anti-mouse probe, and 150 µm with the SA@SWCNT probe (Fig. 3 H–J). Fig. 3K and SI Appendix, Fig. S10 present the 3D overlay and individual images of the three-color channels. Although the imaging depth increased marginally in the NIR-II nuclear stain compared with the shorter-wavelength NIR-I nuclear stain, many factors other than the imaging wavelength contribute to the maximum attainable staining depth. These factors include the limited probe diffusion depths of small-molecule vs. nanomaterial-labeled proteins into tissues, receptor-ligand binding strength, variable fluorophore QYs [>10% for Deep Red (45, 46), 1.9% for IR-FGP, and 0.01–0.05% for SWCNTs (22)], as well as NIR-II detector and integrated optical path conditions of the home-built confocal setup (47). Therefore, to achieve deeper scanning depths with high spatial resolution for one-photon–based systems, NIR-II conjugates with higher QYs, improved staining conditions allowing deeper probe diffusion into fixed tissues, as well as optimized NIR-II confocal setups are needed.

Conclusion

We have described the functional design of a clickable NIR-II small-molecule dye capable of high-efficiency conjugation through copper-free click chemistry. Growing interest in NIR-II imaging mandates the production of high-quality molecular probes, yet most NIR-II fluorophore conjugates do not allow purification through standard techniques. Density gradient separation is proving to be a versatile method capable of resolving both IR-FGP and laser-vaporization SWCNT conjugates. Not just one small molecule and one nanomaterial fluorophore were labeled with a variety of proteins, the developed separation methods should allow purification of a multitude of fluorophores from each material class. Multicolor imaging is extended to 1,700 nm, beyond the typical range of 400–900 nm. This opens a whole new range of imaging wavelengths and provides many more targeting channels for the optical imaging field. The development of a panel of NIR-II molecular probes will allow the fluorescence imaging community to truly benefit from the improved optical imaging metrics garnered by long-wavelength NIR-II imaging. In the NIR-II window, the enhanced imaging depth allows 3D molecular imaging using a simple one-photon technique. To further multiplex fluorophores in the NIR-II range, purified conjugates with higher QYs, narrow emission wavelengths, and large Stokes shifts are highly desired.

Materials and Methods

The materials and methods used in this study are described in detail in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods. Information includes descriptions of IR-FGP design and synthesis, bioconjugation and purification, cell and tissue staining, assay testing, and NIR-II confocol setup.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Calbrain Program and the National Institutes of Health R01 HL127113-01A1 (to H.D.). Y.L. received financial support from the South University of Science and Technology of China, the Recruitment Program of Global Youth Experts of China, Shenzhen Key Lab Funding Grant ZDSYS201505291525382 and the Shenzhen Peacock Program Grant KQTD20140630160825828. This work was also supported by the International Postdoctoral Exchange Fellowship Program 2015 funded by the Office of China Postdoctoral Council Award 20150031; Jilin/Stanford University (to S.Z.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1617990114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Giepmans BN, Adams SR, Ellisman MH, Tsien RY. The fluorescent toolbox for assessing protein location and function. Science. 2006;312(5771):217–224. doi: 10.1126/science.1124618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hong G, Diao S, Antaris AL, Dai H. Carbon nanomaterials for biological imaging and nanomedicinal therapy. Chem Rev. 2015;115(19):10816–10906. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boulina M, Samarajeewa H, Baker JD, Kim MD, Chiba A. Live imaging of multicolor-labeled cells in Drosophila. Development. 2013;140(7):1605–1613. doi: 10.1242/dev.088930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xing Y, et al. Bioconjugated quantum dots for multiplexed and quantitative immunohistochemistry. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(5):1152–1165. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Longmire M, Kosaka N, Ogawa M, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Multicolor in vivo targeted imaging to guide real-time surgery of HER2-positive micrometastases in a two-tumor coincident model of ovarian cancer. Cancer Sci. 2009;100(6):1099–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01133.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy JE, et al. PbTe colloidal nanocrystals: Synthesis, characterization, and multiple exciton generation. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(10):3241–3247. doi: 10.1021/ja0574973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong G, et al. Multifunctional in vivo vascular imaging using near-infrared II fluorescence. Nat Med. 2012;18(12):1841–1846. doi: 10.1038/nm.2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ju SY, Kopcha WP, Papadimitrakopoulos F. Brightly fluorescent single-walled carbon nanotubes via an oxygen-excluding surfactant organization. Science. 2009;323(5919):1319–1323. doi: 10.1126/science.1166265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yi H, et al. M13 phage-functionalized single-walled carbon nanotubes as nanoprobes for second near-infrared window fluorescence imaging of targeted tumors. Nano Lett. 2012;12(3):1176–1183. doi: 10.1021/nl2031663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, et al. Ag2S quantum dot: A bright and biocompatible fluorescent nanoprobe in the second near-infrared window. ACS Nano. 2012;6(5):3695–3702. doi: 10.1021/nn301218z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naczynski DJ, et al. Rare-earth-doped biological composites as in vivo shortwave infrared reporters. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2199. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong G, et al. Through-skull fluorescence imaging of the brain in a new near-infrared window. Nat Photonics. 2014;8(9):723–730. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2014.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naczynski DJ, et al. X-ray-induced shortwave infrared biomedical imaging using rare-earth nanoprobes. Nano Lett. 2015;15(1):96–102. doi: 10.1021/nl504123r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai HH, et al. Oligodendrocyte precursors migrate along vasculature in the developing nervous system. Science. 2016;351(6271):379–384. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gleave JA, Lerch JP, Henkelman RM, Nieman BJ. A method for 3D immunostaining and optical imaging of the mouse brain demonstrated in neural progenitor cells. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e72039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray E, et al. Simple, scalable proteomic imaging for high-dimensional profiling of intact systems. Cell. 2015;163(6):1500–1514. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koh B, et al. Visible to near-infrared fluorescence enhanced cellular imaging on plasmonic gold chips. Small. 2016;12(4):457–465. doi: 10.1002/smll.201502182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong G, et al. Near-infrared II fluorescence for imaging hindlimb vessel regeneration with dynamic tissue perfusion measurement. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7(3):517–525. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.000305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun Y, et al. Novel benzo-bis(1,2,5-thiadiazole) fluorophores for in vivo NIR-II imaging of cancer. Chem Sci. 2016;7(9):6203–6207. doi: 10.1039/c6sc01561a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong G, et al. Syringe injectable electronics: Precise targeted delivery with quantitative input/output connectivity. Nano Lett. 2015;15(10):6979–6984. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dang X, et al. Layer-by-layer assembled fluorescent probes in the second near-infrared window for systemic delivery and detection of ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(19):5179–5184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521175113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diao S, et al. Fluorescence imaging in vivo at wavelengths beyond 1,500 nm. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54(49):14758–14762. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du Y, et al. Near-infrared photoluminescent Ag2S quantum dots from a single source precursor. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(5):1470–1471. doi: 10.1021/ja909490r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang C, et al. Tumor metastasis inhibition by imaging-guided photothermal therapy with single-walled carbon nanotubes. Adv Mater. 2014;26(32):5646–5652. doi: 10.1002/adma.201401825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi HS, et al. Targeted zwitterionic near-infrared fluorophores for improved optical imaging. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(2):148–153. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Z, et al. A symmetrical fluorous dendron-cyanine dye-conjugated bimodal nanoprobe for quantitative 19F MRI and NIR fluorescence bioimaging. Adv Healthc Mater. 2014;3(8):1326–1333. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201400088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yan X, et al. Enhanced fluorescence imaging guided photodynamic therapy of sinoporphyrin sodium-loaded graphene oxide. Biomaterials. 2015;42:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu G, Niu G, Chen X. Aptamer-drug conjugates. Bioconjug Chem. 2015;26(11):2186–2197. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hermanson GT. Bioconjugate Techniques. 3rd Ed Academic; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghosh S, Bachilo SM, Weisman RB. Advanced sorting of single-walled carbon nanotubes by nonlinear density-gradient ultracentrifugation. Nat Nanotechnol. 2010;5(6):443–450. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Antaris AL, et al. A small-molecule dye for NIR-II imaging. Nat Mater. 2016;15(2):235–242. doi: 10.1038/nmat4476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang XD, et al. Traumatic brain injury imaging in the second near-infrared window with a molecular fluorophore. Adv Mater. 2016;28(32):6872–6879. doi: 10.1002/adma.201600706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woo SJ, et al. Synthesis and characterization of water-soluble conjugated oligoelectrolytes for near-infrared fluorescence biological imaging. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(25):15937–15947. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b04276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qian G, et al. Band gap-tunable, donor−acceptor−donor charge-transfer heteroquinoid-based chromophores: Near-infrared photoluminescence and electroluminescence. Chem Mater. 2008;20(19):6208–6216. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hudak JE, et al. Synthesis of heterobifunctional protein fusions using copper-free click chemistry and the aldehyde tag. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51(17):4161–4165. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berg JM, Tymoczko JL, Stryer L. 2002. SEC, size exclusion chromatography. Biochemistry (W. H. Freeman, New York)

- 37.Zhang B, Kumar RB, Dai H, Feldman BJ. A plasmonic chip for biomarker discovery and diagnosis of type 1 diabetes. Nat Med. 2014;20(8):948–953. doi: 10.1038/nm.3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang B, et al. An integrated peptide-antigen microarray on plasmonic gold films for sensitive human antibody profiling. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e71043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li X, et al. Multiplexed anti-toxoplasma IgG, IgM, and IgA assay on plasmonic gold chips: Towards making mass screening possible with dye test precision. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(7):1726–1733. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03371-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Welsher K, Sherlock SP, Dai H. Deep-tissue anatomical imaging of mice using carbon nanotube fluorophores in the second near-infrared window. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(22):8943–8948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014501108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Welsher K, et al. A route to brightly fluorescent carbon nanotubes for near-infrared imaging in mice. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4(11):773–780. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cao R, et al. Mouse corneal lymphangiogenesis model. Nat Protoc. 2011;6(6):817–826. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu X, et al. Molecular imaging of drug transit through the blood-brain barrier with MALDI mass spectrometry imaging. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2859. doi: 10.1038/srep02859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kozai TD, et al. Ultrasmall implantable composite microelectrodes with bioactive surfaces for chronic neural interfaces. Nat Mater. 2012;11(12):1065–1073. doi: 10.1038/nmat3468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson I, Spence MTZ, editors. The Molecular Probes Handbook, A Guide to Fluorescent Probes and Labeling Technologies. 11th Ed Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rurack K, Spieles M. Fluorescence quantum yields of a series of red and near-infrared dyes emitting at 600–1000 nm. Anal Chem. 2011;83(4):1232–1242. doi: 10.1021/ac101329h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Welsher K, Yang H. Multi-resolution 3D visualization of the early stages of cellular uptake of peptide-coated nanoparticles. Nat Nanotechnol. 2014;9(3):198–203. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.