Significance

The induction of tolerance is still an ideal and largely unachieved goal in the transplantation and autoimmunity fields. Understanding natural allotolerance mechanisms could help realize this objective. In this study we found that maternal microchimerism generated “split” tolerance, stimulating classical alloreactivity (i.e., recognition of intact peptide/allo-MHC class II complexes by CD4 T cells), while silencing CD4 T cells responding to allopeptide in a self-MHC–restricted manner. These contrary activities could be attributed to the presence of separate antigenic microdomains with different costimulatory properties on the surface of a single host dendritic cell. The possibility that this state develops from interaction with a microchimerism-derived extracellular vesicle has important implications for cell biology, cancer immunotherapy, and molecular immunology.

Keywords: dendritic cells, exosomes, split tolerance, T cells, microchimerism

Abstract

Maternal microchimerism (MMc) has been associated with development of allospecific transplant tolerance, antitumor immunity, and cross-generational reproductive fitness, but its mode of action is unknown. We found in a murine model that MMc caused exposure to the noninherited maternal antigens in all offspring, but in some, MMc magnitude was enough to cause membrane alloantigen acquisition (mAAQ; “cross-dressing”) of host dendritic cells (DCs). Extracellular vesicle (EV)-enriched serum fractions from mAAQ+, but not from non-mAAQ, mice reproduced the DC cross-dressing phenomenon in vitro. In vivo, mAAQ was associated with increased expression of immune modulators PD-L1 (programmed death-ligand 1) and CD86 by myeloid DCs (mDCs) and decreased presentation of allopeptide+self-MHC complexes, along with increased PD-L1, on plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs). Remarkably, both serum EV-enriched fractions and membrane microdomains containing the acquired MHC alloantigens included CD86, but completely excluded PD-L1. In contrast, EV-enriched fractions and microdomains containing allopeptide+self-MHC did not exclude PD-L1. Adoptive transfer of allospecific transgenic CD4 T cells revealed a “split tolerance” status in mAAQ+ mice: T cells recognizing intact acquired MHC alloantigens proliferated, whereas those responding to allopeptide+self-MHC did not. Using isolated pDCs and mDCs for in vitro culture with allopeptide+self-MHC–specific CD4 T cells, we could replicate their normal activation in non-mAAQ mice, and PD-L1–dependent anergy in mAAQ+ hosts. We propose that EVs provide a physiologic link between microchimerism and split tolerance, with implications for tumor immunity, transplantation, autoimmunity, and reproductive success.

Immunologic tolerance was originally described in 1945 as a state of 50:50 mixed chimerism in dizygotic bovine twins (1), a discovery that launched modern immunogenetics and remains the gold standard for organ transplantation tolerance (2). Conversely, maternal microchimerism (MMc), common to all mammals, imposes a partial form of immunologic tolerance. Female offspring gain cross-generational fitness in the form of acquired resistance to loss of a fetus bearing inherited paternal antigens (IPAs) identical to her noninherited maternal antigens (NIMAs) (3, 4). MMc also has a strong impact in transplantation. Significantly longer graft and patient survival is achieved under a standard immunosuppressive regimen in recipients of a sibling kidney or bone marrow transplant that expresses the NIMA haplotype as the HLA mismatch (5, 6).

Paradoxically, NIMA+ sibling kidney transplants had a significant increase in early acute rejection episodes, followed by comparative freedom from late graft loss, compared with sibling transplants mismatched for noninherited paternal antigens (5). The basis for such conflicting manifestations of preexisting MMc is that such tolerance is split. The indirect allorecognition pathway, whereby host antigen-presenting cells (APCs) present processed allopeptides bound to self–MHC-II (major histocompatibility complex) molecules to CD4 Th cells (7), is anergic or suppressed (8–10). In contrast, conventional allorecognition of maternal target cells by T cells in adults (known as direct alloreactivity) is intact (11, 12). The latter seems to be largely responsible for early acute rejection of organ transplants (13). Curiously, the persistence of exposure to certain NIMA-HLA may lead to increased or decreased risk of certain rheumatoid diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis) depending on the NIMA-HLA haplotype (14, 15).

The transfer of membrane-bound intact allo-MHC molecules from the allogeneic cell to host dendritic cells (DCs) has been described (16). This membrane alloantigen acquisition (mAAQ), also known as cross-dressing (17), can occur by extracellular vesicle (EV) exchange. Importantly, mAAQ gives rise to a subset of host DCs that express intact allo-MHC molecules on the cell surface, while also presenting processed allopeptides, thus allowing a single DC to interact with both directly alloreactive CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes and indirect pathway CD4+ Th cells (16) (18). This process has recently been shown to be critical to a direct pathway, acute rejection response in organ transplantation (19, 20). Furthermore, because certain EVs, like exosomes, contain microRNAs (miRNAs), acquisition leads not only to surface expression of intact transferred allo-MHC/peptide complexes, but can also change the functional status of the mAAQ+ DC (21). Here, we used a mouse model to determine whether the amplification mechanism of MMc and the split nature of the tolerance it induces might be consequences of functional changes in host DCs caused by EV acquisition from rare maternal cells.

Results

Maternal mAAQ Is Found in Some, but Not All, H-2b/b Mice Born to H-2b/d Mothers.

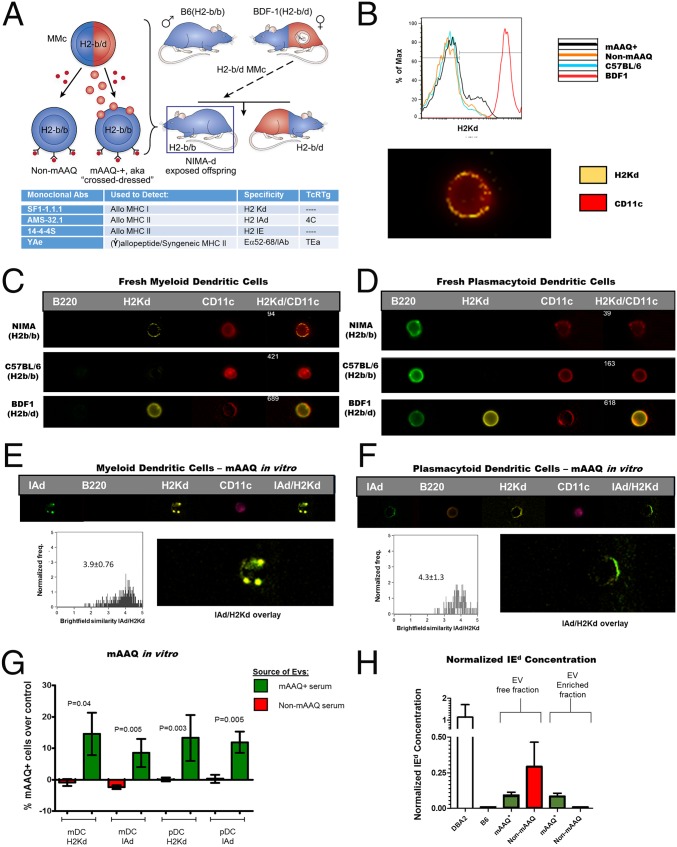

Homozygous H2b adult offspring of a BDF1♀ x C57BL/6♂ backcross (H2b mice exposed to H2d plus other noninherited antigens of DBA/2 origin during the pregnancy/nursing period; hereafter referred to as NIMAd mice) were analyzed for mAAQ. Fig. 1A illustrates the breeding scheme, the generation of mAAQ in some of the b/b offspring from products of MMc, and the types of antibodies and T-cell receptor transgenics (TcR Tg) used to characterize the model. Both non-mAAQ and mAAQ+ mice expressed the allopeptide/MHC-II Eα52–68/I-Ab complex, indicated by (Ẏ) at the surface of their DCs. We defined mAAQ+ status (represented by cell-bound spheres in Fig. 1A) as dim H2Kd expression by flow cytometry (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1). The incidence of mAAQ+ status in NIMAd mice was 45% (31/68), similar in males and females. In adult mAAQ+ offspring, the proportion of H2Kd-dim DC was quite variable (range 1–25%; mean ± SD = 5.32 ± 5.84%) and was detectable on fresh myeloid DCs (mDCs), but no other subpopulations (Fig. S1). Using imaging flow cytometry, we found that splenic mAAQ+ mDCs could be clearly distinguished by an uneven punctate/patchy surface distribution of H2Kd staining (Fig. 1 B and C), whereas freshly isolated plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) did not show any evidence of mAAQ (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

NIMAd model breeding strategy, and mAAQ phenomenon. (A) Scheme showing the breeding strategy of BDF1♀ (H2b/d) x C57BL/6♂ (H2b/b) backcross. From this breeding, ∼50% of offspring are H2b/b, which were exposed to H2d NIMAs during the fetal and nursing period. Some NIMAd mice developed sufficient levels of semiallogeneic MMc to receive NIMAs (like H2d antigens) from MMc sources via exosomes (red spheres), leading to mAAQ. All NIMAd offspring, including non-mAAQ mice, developed expression of maternal allopeptides bound to self-MHC (Ẏ). H2d and H2b antigens are represented in red and blue, respectively. (B) Flow cytometry (Upper) showing H2Kd expression (black line) typical of mAAQ, and microscopic patchy/uneven pattern of H2Kd acquisition by mDCs (Lower; imaging flow cytometry). (C) Natural patterns of H2Kd acquisition (mAAQ) (vs. controls) by mDCs (microscopy flow cytometry; ImageStream 60×). (D) mAAQ was not detectable in fresh pDCs. (E and F) mAAQ phenomenon was replicated in vitro by incubating C57BL/6 DCs with EVs derived from the serum of mAAQ+ mice. Both mDCs (E) and pDCs (F) acquired H2Kd when incubated with EVs, but with different microscopic pattern. For imaging flow cytometry analysis, n = 3 mice per group, and 50–200 H2Kd-dim events were analyzed per mouse. (G) Summary of independent EV-DCs culture experiments (n = 7 for mAAQ+–EV-enriched serum fractions and n = 6 for EV fractions from non-mAAQ mice). The mean ± SD of percent mAAQ+ B6 mDC and pDC after incubation with EV fractions from mAAQ+ vs. mAAQneg serum, over B6 negative control EV fraction, is plotted. (H) I-Ed ELISA analysis of serum and its fractions (SI Materials and Methods for details). ImageStream magnification of panels B–F: 60×.

Fig. S1.

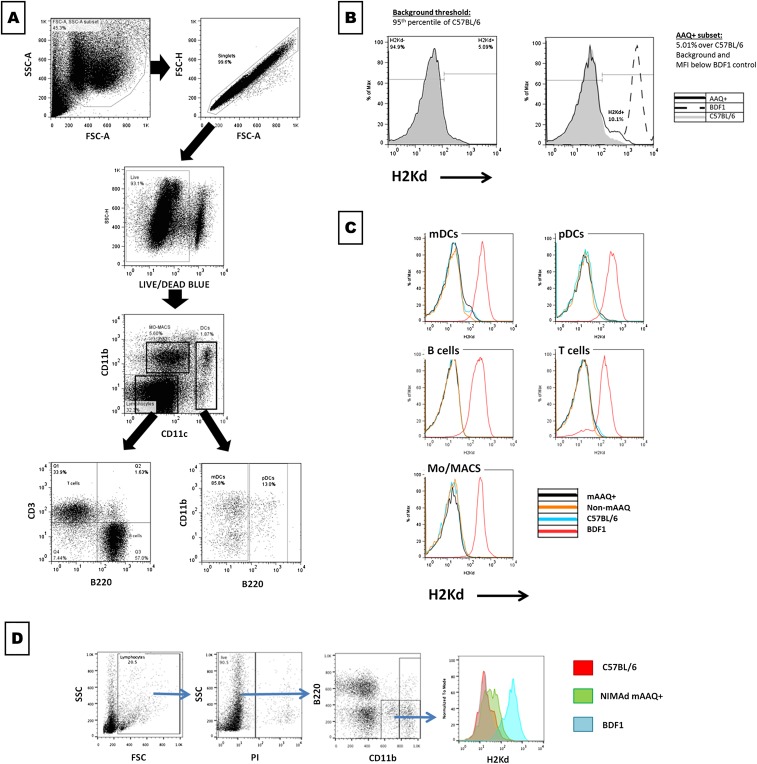

Gating strategy and mAAQ detection. (A) Gating strategy for mAAQ detection is shown. Live splenocytes were gated based on FSC-A/SSC-A, exclusion of doublets (FSC-A/FSC-H) and death cells (Live/Dead blue stain). Then, CD11b vs. CD11c gated on monocytes/macrophages (CD11b+CD11clow), yielded true DCs (CD11c+), which then were discriminated between mDCs and pDCs, depending on B220 expression. Based on CD3 vs. B220 expression, the CD11bnegCD11cneg population was separated into B and T cells. (B) For mAAQ analysis of each subset, a threshold was imposed in the 95th percentile of H2Kd expression in the C57BL/6 negative control of each experiment and applied to each experimental sample (this was based on the typical background observed in C57BL/6 mice in our experimental conditions). mAAQ was considered positive if the sample showed a H2Kd dim subpopulation 1% over the threshold (negative control background) and a MFI lower than the positive control (BDF1). mAAQ analysis was performed routinely on splenocytes, collecting 750,000–1,000,000 events. (C) mAAQ in fresh cells was detectable on mDCs (Upper Left), but not in other subsets (Mo/MACS, pDCs, B cells, or T cells). An example is shown of lack of mAAQ in these subsets, even though there was a low, but detectable, signal on mDCs. (D) mAAQ was also detectable on PBMCs in the CD11b+B220neg subset. Despite the low number of events in a small blood sample obtainable from each mouse (<0.5 cc), we could use peripheral blood to screen for mAAQ status, then confirm by hemisplenectomy and FACS analysis.

Serum (EV)-Enriched Fractions Replicate the mAAQ Phenomenon in Vitro.

EV-enriched serum fractions from non-mAAQ and mAAQ+ mice were obtained by using various approaches (Materials and Methods). Fig. S2 shows the characterization of EV-enriched fractions obtained using matrix precipitation. EV-enriched serum fractions from individual mice were cultured with C57BL/6 splenocytes to determine whether they could generate mAAQ. C57BL/6- and BDF1-derived serum EV were used as negative and positive controls, respectively.

Fig. S2.

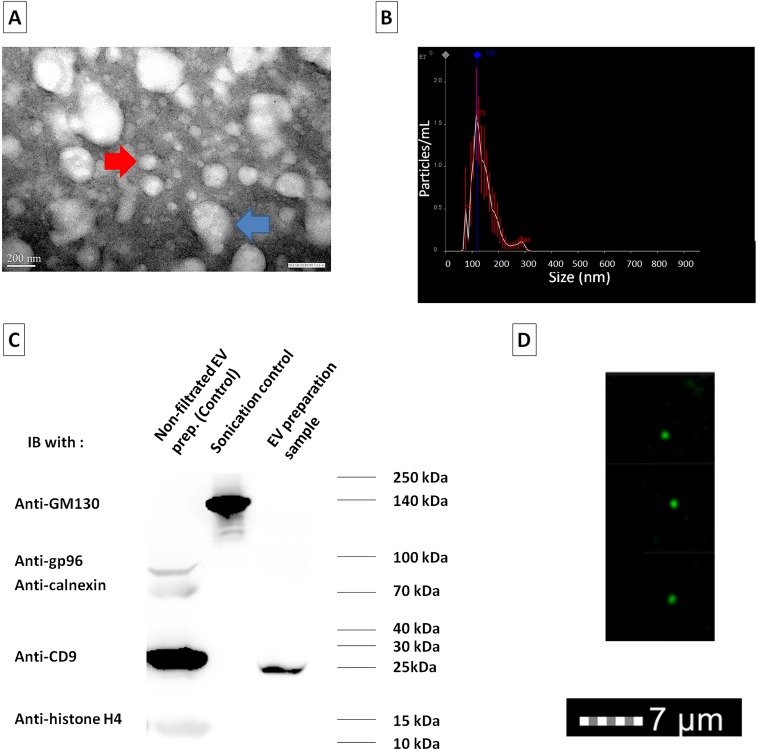

Characterization of EV-enriched serum fractions. (A) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) shows that isolated EVs were in the nanovesicle size range and morphology. Some aggregates of EVs can be observed (two or three clustered EVs; blue arrow; 278-nm diameter). Nevertheless, single isolated EVs (red arrow; 122-nm diameter) had a mean diameter of 90.4 ± 12 nm by visual measurement (n = 23 vesicles)—that is, compatible with the dimensions of exosomes. (B) NanoSight technology allowed the estimation of vesicle diameter in a larger aliquot (n = 9,000) of the EV preparation. All EVs and aggregates < 500 nm in diameter were included in the histogram. A mean diameter of 138 ± 10 nm was estimated by this method, with smaller peaks at 75 and 285 and a major peak at 115. (C) Western blot was performed for exosome marker (CD9), as well as markers of potential contaminating vesicles: endoplasmic reticulum (Calnexin, gp96), nuclear vesicles (histone H4), and Golgi-derived vesicles (GM130). The EV preparation (third lane) was clearly enriched for exosome marker CD9, with a negligible contamination of markers of other types of EVs (this was the type of preparation used in the experiments in Fig. 3). Samples obtained with the matrix-based isolation method (Invitrogen), but without a final 0.45-μm nanofiltration (corresponding to first lane), contain a high amount of exosome markers, and a low, but detectable, level of contamination of nuclear and ER proteins (Calnexin, gp96, and histone H4). Sonication of splenocytes followed by clearance of nuclear sand ER debris by 15,000 × g centrifugation was used as positive control for Golgi-derived vesicles (GM130), clearly absent from both serum EV fractions. (D) ImageStream (flow microscopy) was also used to corroborate existence of exosomes in the EVs’ preparations. A predominance of nanovesicles <0.5 μm in diameter were stained with CD9+ (green). Together, the TEM, NanoSight, Western blot, and ImageStream data strongly suggest that the samples of serum-derived EVs obtained to perform the immunologic experiments were highly enriched in exosome content.

EV fractions from mAAQ+ mice induced acquisition of H2Kd and IAd on both mDCs and pDCs between 6 and 24 h of culture (Fig. 1 E and F shows the 6-h data). Conversely, EV fractions from non-mAAQ mice induced neither Kd nor IAd acquisition by C57BL/6 splenocytes; results were no different from the negligible mAAQ signal (background) detected after incubation with control C57BL/6-derived EV (Fig. 1G). Thus, serum EV-enriched fractions from non-mAAQ vs. mAAQ+ mice were significantly different in their ability to cause appearance of MHC-I and -II intact alloantigens on the surface of both pDCs and mDCs.

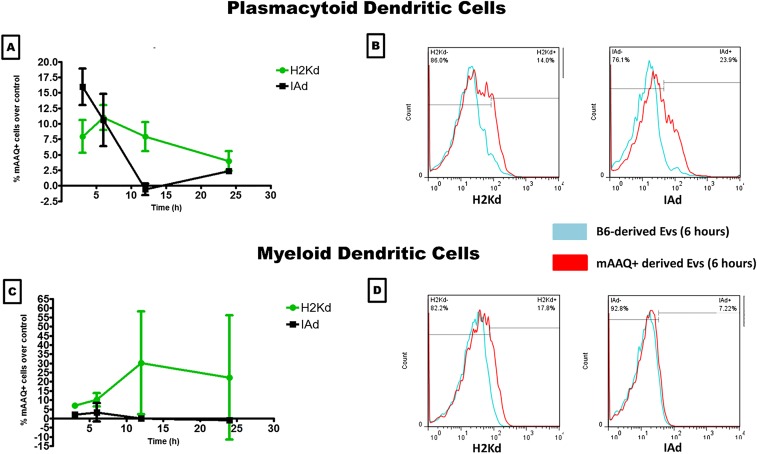

The mDC >> pDC bias of mAAQ noted in vivo did not appear to arise from differences in ability to reexpress intact H2Kd and IAd. In vitro, both antigens remained highly colocalized on either DC subset [Brightfield similarity index (BSI) = 3.9–4.3, where values >1 represent significant colocalization], suggesting similar retention of antigen integrity and association pattern. However, differences in kinetics of EV uptake and reexpression were striking. After 6 h of in vitro exposure to EV-enriched serum fractions from mAAQ+ mice, imaging flow cytometry of B6 mDC revealed a punctate, spherical expression of H2Kd and IAd, suggesting cell-bound intact EVs, along with some membrane alloantigen incorporation (Fig. 1E). In contrast, B6 pDCs displayed both alloantigens evenly, with no retained EVs at this time point (Fig. 1F). The more rapid EV uptake and reexpression of allo-MHC (particularly I-Ad) by pDCs was transient compared with mDCs, on which mAAQ continued to increase up to 12 h and stabilized at 24 h (Fig. S3).

Fig. S3.

Kinetics of the mAAQ phenomenon in vitro. Differential kinetics of MHC-I and -II acquisition by B6 pDC vs. mDC during coculture with BDF1 EV serum fractions are shown. A and C show the timeline kinetics of mAAQ, demonstrating early and transient (peak at 3–6 h) of MHC-I (H2Kd; green) and MHC-II (IAd; black) acquisition by pDCs (A). Conversely, mDCs predominantly acquired MHCI in a progressive and sustained manner (C). In B and D, examples of H2Kd and IAd acquisition by pDCs (B) and mDCs (D) are shown at 6 h. Negative control (culture with B6-derived EVs) histograms are shown in blue, and experimental histograms (culture with mAAQ+-derived EVs) are shown in red.

To investigate further the forms of NIMAd in serum of non-mAAQ vs. mAAQ+ mice, we analyzed 100,000 × g ultracentrifuged fractions of serum by ELISA (Materials and Methods). As expected because of a mutation in the Eα locus in H-2b strains, B6 serum was completely negative for I-E antigen (Fig. 1H), compared with positive control (DBA/2) serum. Therefore, in the H2b/b, NIMAd backcross mouse, the only source of I-E would be rare BDF1 (maternal) cells. Surprisingly, a strong I-E signal was detected in serum from non-mAAQ NIMAd mice, but only in the EV-free fraction (Fig. 1H). In mAAQ+ mouse serum, we detected I-E in both EV-free and EV-enriched fractions of serum, indicating that maternally derived MHC-II+ cells had generated both membrane-bound and free soluble forms of alloantigen. The ELISA data are thus consistent with the in vitro mAAQ data, and with quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis of bone marrow MMc (see Microchimerism Analysis) that reinforce the idea that, although all NIMAd offspring have some MMc and are chronically exposed to maternal soluble MHC, only mAAQ+ mice have sufficient MMc to generate EVs capable of cross-dressing host APCs.

Analysis of DC, Serum EV, and EV-Free Fractions for Patterns of PD-L1 and CD86 Coexpression.

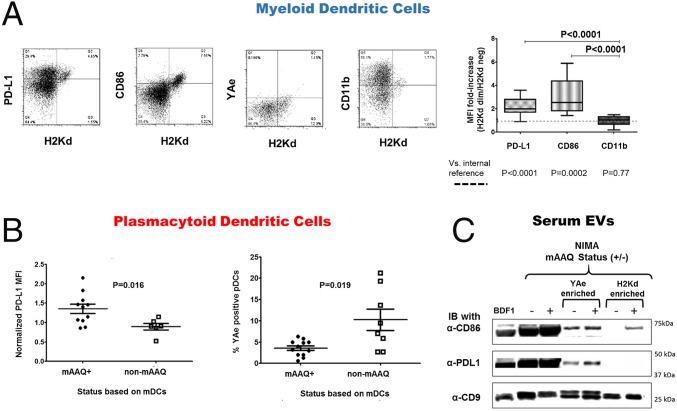

To determine whether cross-dressing had altered the DCs of mAAQ+ mice in either (i) the pattern of costimulatory molecule expression or (ii) the expression of allopeptide/self–MHC-II complexes, those features were analyzed in freshly isolated splenocytes. By comparing the H2Kd-dim with H2Kd-neg mDCs from the same mAAQ+ mouse by flow cytometry, we observed that PD-L1 (programmed death-ligand 1) and CD86 were overexpressed in the H2Kd-dim (mAAQ+) subset of mDCs (Fig. 2A). CD11b expression remained unchanged.

Fig. 2.

Analysis of DCs immunophenotype and EVs PD-L1 and CD86 content. (A) Flow cytometry dot plots of H2Kd vs. PD-L1, CD86, YAe, or CD11b on mDCs of mAAQ+ mice. Note that the subset of H2Kd dim mDCs highly express surface PD-L1 and CD86. No substantial changes were found in YAe or CD11b expression in mAAQ+ DC (n = 18). Statistical analysis demonstrates a significant increase in PD-L1 and CD86 expression on H2Kd dim mDC subset in mAAQ+ mice (2.2 ± 0.74 and 3.07 ± 1.54 fold increase, respectively; P < 0.0001) by geometric mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) fold increase. (B) MFI of PD-L1 expression in the entire pDC population was estimated, and the average within mAAQ+ mice was compared with the average expression in non-mAAQ mice. A significant increase in PD-L1 expression was observed in the pDCs of mice with detectable mAAQ among mDCs. The same pDC population showed a significant decrease in YAe (allopeptide/MHC-II) expression compared with pDCs from non-mAAQ mice. Dot plots show mean ± SD. (C) Immunoblot (IB) of EV-enriched serum samples separated on SDS/PAGE. Far left sample is from normal BDF1 serum EV; all others are from NIMAd mice. The + or – in parentheses indicates the mAAQ status of the NIMAd mice. Lanes 1–3 (from left) show total EV; lanes 4 and 5 show YAe-enriched; and lanes 6 and 7 show anti-Kd-enriched fractions. After transfer, anti-CD9 was used as an EV/exosome marker, and antibodies to CD86 and PD-L1 were tested by IB to determine costimulator/coinhibitor content of each EV sample.

Although a H2Kd-dim subset was not discernible in fresh pDCs (Fig. 1 D and F and Fig. S1), PD-L1 expression was significantly increased overall on pDCs of mAAQ+ vs. non-mAAQ mice (Fig. 2B). The pDCs from mAAQ+ mice showed a significantly reduced expression of the Eα52–68 peptide-IAb complex recognized by the YAe monoclonal antibody (hereafter referred to as the “YAe epitope”), compared with pDCs of non-mAAQ mice (Fig. 2B and Fig. S4).

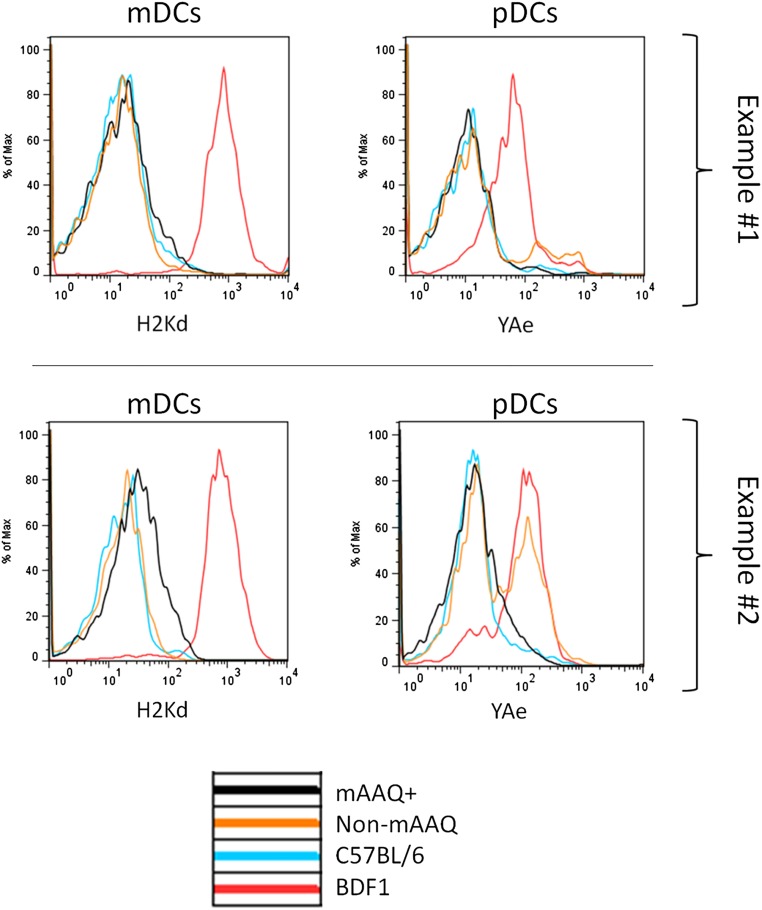

Fig. S4.

Examples of surface expression of Kd and YAe epitopes on mDCs and pDCs. Examples of the higher proportion of YAe+ pDCs was observed in NIMAd mice with no detectable H2Kd dim subpopulation among mDCs (non-mAAQ), compared with mAAQ+ mice. Example 1 is a representative one, and example 2 is the most extreme one. Overall expression of IAb was independent of mAAQ status (not shown), suggesting that the inhibition of YAe expression by pDCs of mAAQ+ mice was not due to lack of IAb for binding Eα52-68 peptides.

To further characterize the serum EV fractions, we analyzed them by immunoprecipitation, SDS/PAGE, and Western blot. As shown in Fig. 2C, EV-enriched serum fractions from both mAAQ+ and non-mAAQ NIMAd mice, like EV from BDF1, contained the exosome-associated tetraspanin CD9, as noted by imaging flow cytometry and Western blot (Fig. S2). Total EV derived from mAAQ+ mouse serum and from non-mAAQ mice had abundant PD-L1 and CD86 (Fig. 2C, lanes 2 and 3), as did control BDF1 EV (lane 1). However, when serum EV fractions were enriched for YAe (Fig. 2C, lanes 4 and 5) or H-2Kd expression (lanes 6 and 7), differences in costimulatory molecule expression emerged. The YAe-enriched EV fraction from mAAQ+ and non-mAAQ mouse serum contained both CD86 and PD-L1. However, the H2Kd-enriched fraction of mAAQ+ EV contained CD86, but not PD-L1 (Fig. 2C, lane 7). H2Kd enrichment of EV fractions from non-mAAQ mouse serum produced no signal for either CD86 or PD-L1. Together, these data suggest that mAAQ was associated with cotransfer of CD86 along with class I and II allo-MHCs. Unlike CD86, PD-L1 expression in the mAAQ+ DCs did not appear to arise from EV protein transfer, suggesting an induction of endogenous PD-L1 expression by another component of the EV.

Microchimerism Analysis.

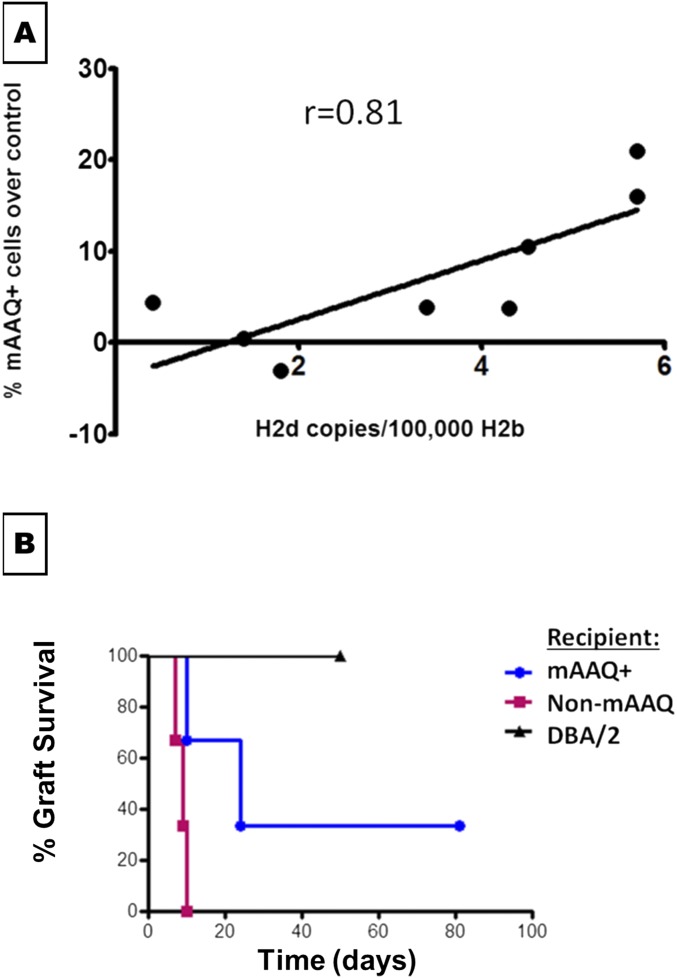

In a group of eight NIMAd mice, all but one had some level of MMc in bone marrow detectable by qPCR assay. A linear correlation between the MMc level and the proportion of mAAQ+ mDCs (r = 0.81, P = 0.01) was observed (Fig. S5A). These data are consistent with the ELISA results for serum I-E (Fig. 1H). Together, they indicate that, although nearly all NIMAd mice were microchimeras for maternal MHC-II+ cells, the mAAQ+ phenotype required a higher level of MMc.

Fig. S5.

Association of mAAQ with MMc level in bone marrow by qPCR (A) and tolerance to a DBA/2 heart allograft (B). (A) Bone marrow from NIMAd mice were harvested to detect MMc level (qPCR with H2Dd primers). A significant correlation was observed between the amount of maternal cells (level of MMc) in the bone marrow and the magnitude of mAAQ (percentage of H2Kd dim mDCs). (B) Fully mismatched heterotopic heart transplantation (DBA/2 donor, expressing NIMA H2d) were performed in mAAQ+ (n = 3) and non-mAAQ (n = 3) NIMAd mice. Syngeneic donor–recipient pairs were used as a technical control. Prolongation of graft survival in the mAAQ+ group was observed, with one mouse achieving long-term graft survival. Conversely, non-mAAQ mice all acutely rejected their DBA/2 grafts.

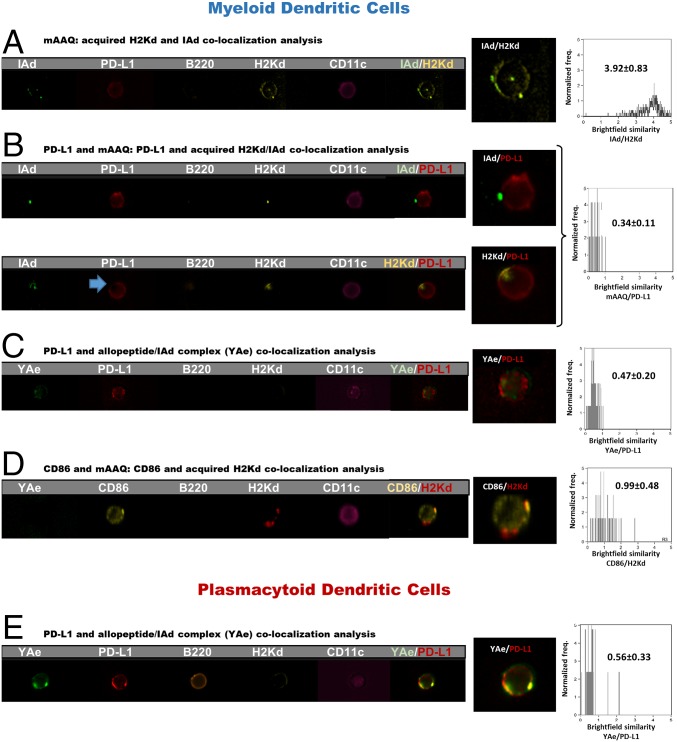

Areas of H-2Kd/IAd Expression on the Surface of Host DCs Exclude PD-L1, Whereas Areas of YAe Expression Do Not.

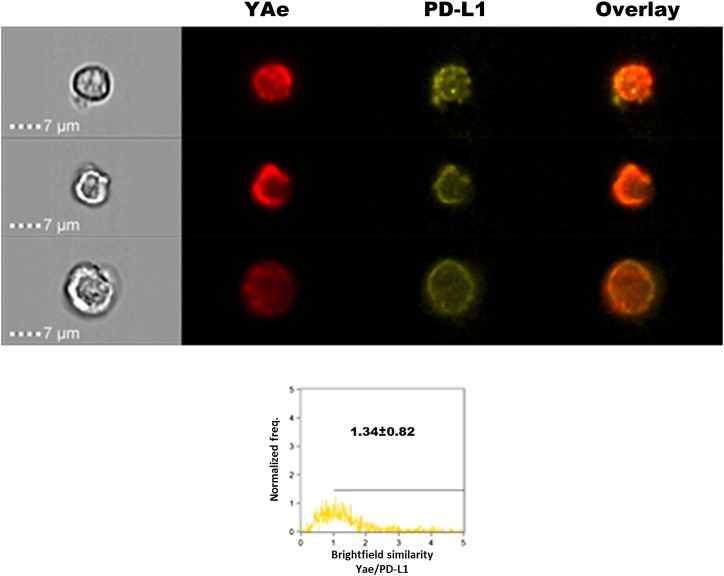

Using imaging flow cytometry, we could detect IAd expression on mAAQ+ mDCs analyzed directly ex vivo (Fig. 3). A high degree of H2Kd/IAd colocalization was observed (Fig. 3A), similar to that seen after in vitro coculture of splenocytes with EV fractions (Fig. 1). CD86 was also colocalized with the mAAQ patches on the mDC (Fig. 3D). However, H2Kd and IAd were not colocalized with PD-L1, which appeared to be completely excluded from the mAAQ patches (Fig. 3B, blue arrow).

Fig. 3.

Different surface distribution of Kd/I-Ad vs. YAe in relation to PD-L1 on mAAQ+ DC. (A) Imaging flow cytometry of fresh mice splenocytes (60×) allowed us to detect H2Kd and IAd acquisition. Both had a similar punctate distribution pattern. Interestingly, they were strongly colocalized on the surface of mDCs. (B) PD-L1 expression was not colocalized either with H2Kd or IAd, being excluded from patches of mAAQ. (C) Some mDCs showed partial colocalization between YAe and PD-L1, demonstrated by events with BSI > 1 and a significantly higher BSI compared with the H2Kd/PD-L1 BSI value. (D) Significant colocalization of CD86 with H2Kd, demonstrating its presence in the patches of acquired alloantigen. (E) Partial H2Kd/PD-L1 colocalization on pDCs. Representative examples are shown. Similar findings were obtained in three independent experiments. Mean ± SD of BSI is reported. Colocalization by BSI were estimated on n = 55–363 DCs per experiment.

On mDCs of mAAQ+ mice, PD-L1 was mostly excluded from areas where the YAe epitope was expressed. Nevertheless, there was a significantly higher YAe/PD-L1 colocalization (BSI) value compared with H2Kd/PD-L1 (P < 0.001; Fig. 3 B and C). On pDCs, the YAe epitope was even more colocalized with PD-L1, with some values of BSI in the 1–2 range (Fig. 3E). These data, along with the presence of PD-L1 in YAe-enriched EV of mAAQ+ mice and its absence in H2-Kd-enriched EV that contain CD86 (Fig. 2C), strongly suggest a difference in the costimulatory context of cross-dressed vs. endogenously processed alloantigen.

To better visualize the PD-L1 context of YAe epitopes arising from the classical MHC-II processing and presentation pathway of the host, we used B6 recipients of a DBA/2 (YAeneg) heart allograft, made tolerant by anti-CD40L treatment. In this fully allogeneic tolerance setting, in which all YAe expression derives from the classical MHC-II pathway and none from cross-dressing, we found that PD-L1 was highly colocalized with the YAe epitope on the surface membrane of splenic mDC (Fig. S6).

Fig. S6.

PD-L1/YAe colocalization on host mDC in a B6 mouse tolerant of a DBA/2 allograft. (Upper) Examples of three different mDCs from spleen of a C57BL/6 mouse tolerized to a fully allogeneic DBA/2 heterotopic heart transplant. MR-1(anti-CD154; 125 μg) was administered on days 0, 2, and 4, and spleen cells were harvested on day 60 after transplantation and immunostained for PD-L1 and YAe. Analysis by imaging flow cytometry of CD11c+,lineage− cells is shown. Overlay indicates numerous yellow (red/green] areas of colocalization on the mDC surface. (Lower) Imaging flow cytometry analysis of BSI for YAe and PD-L1 colocalization on B6 (host) mDCs. Number of events = 1,000. Freq., frequency.

mAAQ Generates Functional Recognition of Intact allo-MHC (Direct Pathway) and Abortive Activation by Allopeptide/MHC (Indirect Pathway).

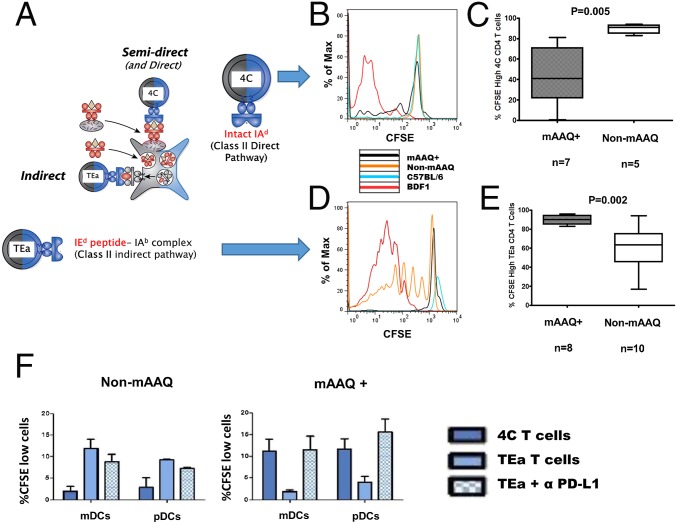

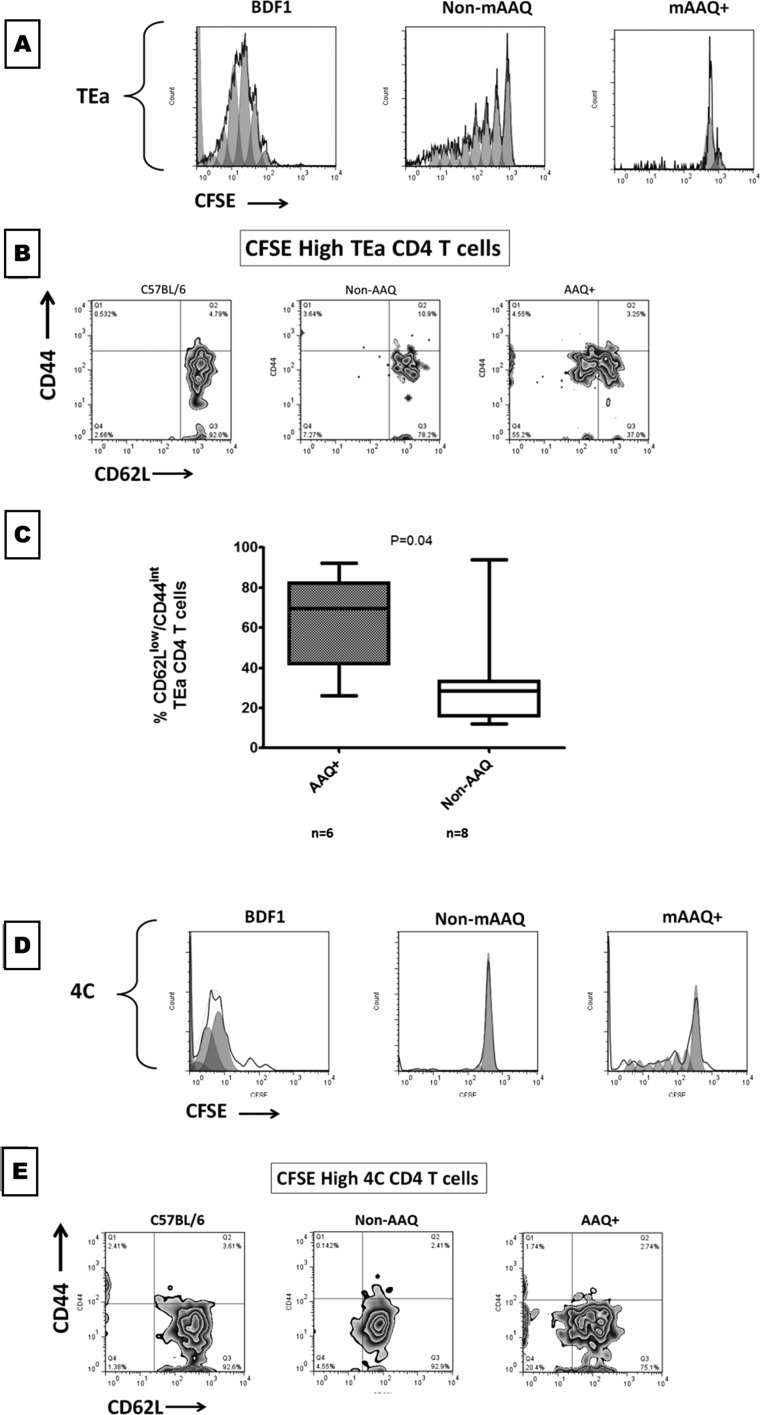

To study the impact of mAAQ on the two major pathways of allorecognition, adoptive transfer experiments were performed with TcR Tg CD4 T cells. Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled 4C T cells, which recognize the intact I-Ad alloantigen, were transferred into NIMAd, C57BL/6, or BDF1 mice. Only BDF1, and mAAQ+ NIMAd mice, induced the proliferation of 4Cs, whereas in non-mAAQ mice, the transferred cells remained unproliferated (Fig. 4 A–C).

Fig. 4.

Inverse response patterns of 4C and TEa CD4+ TcR Tg T cells in vivo and PD-L1 dependence of TEa abortive activation/anergy induced by mAAQ+ DC in vitro. (A) Models of two pathways of alloresponse: (semi) direct recognition of intact allo-MHC antigens (interrogated by 4C TcR Tg CD4 T cells) and indirect recognition (allopeptide presented in a class II restricted manner; interrogated by TEa TcR Tg CD4 T cells). (B) The 4C T cells proliferate in mice with detectable mAAQ (black). No proliferation was observed in a non-mAAQ host (orange). (C) The proportion of divided (CFSE low) 4C cells was significantly higher in mAAQ+ than in non-mAAQ hosts (n = 5–7 experiments). (D) Opposite behavior of TEa T cells was observed in adoptive transfer experiments: Proliferation was observed in non-mAAQ mice, whereas no significant proliferation was observed in mAAQ+ mice (black). (E) The difference of CFSE dilution between mAAQ+ and non-mAAQ hosts was significant. Boxes show median, and whiskers show maximum and minimum. (F) In vitro analysis of alloantigen presentation by DC isolated from non-mAAQ and mAAQ+ mice and corresponding models of microchimerism–DC interaction. We isolated mDCs and pDCs from the spleen of non-mAAQ mice (F, Left) or mAAQ+ mice (F, Right) and tested them for their ability to induce proliferation, as measured by increased percentage of CFSElow CD4 T cells (CFSE-labeled 4C or TEa CD4 T cells in vitro). PD-L1 antibody was added on day 0 to TEa cells cultured with non-mAAQ or mAAQ+ DCs. Bars show mean ± SD (n = 2 experiments, with two replicates each). Max, maximum.

To interrogate the indirect allorecognition pathway, CFSE-labeled TEa cells, CD4 T cells that express a TcR specific for the YAe epitope, were adoptively transferred. No proliferation was seen in negative control B6 mice, whereas in BDF1 mice, all transferred TEa cells proliferated. A substantial portion of TEa cells proliferated in non-mAAQ mice. In contrast, within mAAQ+ mice, no productive proliferation of TEa cells occurred (Fig. 4 D and E). Instead, TEa cells in mAAQ+ hosts underwent abortive activation based on two criteria: (i) Cell-cycle analysis indicated that up to 80% of the TEa cells in the mAAQ+ recipient underwent one division cycle, whereas only a negligible proportion (<1%) underwent further proliferation (Fig. 4D and Fig. S7A); and (ii) despite arrest after one cell division, there was a significant increase of activated phenotype (Fig. S7 B and C). By contrast, 4C T cells that failed to proliferate after transfer into non-mAAQ hosts retained a naïve phenotype (Fig. S7 D and E). The split-tolerance phenomenon was reflected in prolonged transplantation survival in some, but not all, mAAQ+ vs. non-mAAQ recipients of DBA/2 heart allografts (Fig. S5B). Both T-cell adoptive transfer and allograft studies suggested that the impact of MMc on host DCs could result in either (i) no restraint on alloreactivity, with strong TEa proliferation and uniform acute rejection of heart allografts in non-mAAQ mice; or (ii) split tolerance, with TEa abortive activation coupled with 4C proliferation and acute rejection or long-term DBA/2 heart allograft survival in untreated mAAQ+ mice. The latter results are consistent with the cardinal feature of split tolerance (i.e., a premature and weakened, but still active acute rejection pathway, followed by a relative freedom from chronic rejection) (5, 22).

Fig. S7.

Abortive activation features of TEa cells in vivo. (A) After adoptive transfer experiments, the CFSE dilution analysis was corroborated with a computational analysis of division cycles (FlowJo). TEa cells all proliferated in a BDF1 host (A, Left) and underwent up to eight division cycles in a non-mAAQ, NIMAd-exposed mouse (A, Center). In the mAAQ+ hosts, no significant proliferation occurred. Nevertheless, those cells consistently underwent one division cycle, remaining CFSE-high and stuck in a second cycle according to the computational analysis (A, Right). (B) Activation phenotype (CD62L/CD44) of CFSE-high TCR Tg CD4 T cells (minimally proliferated) was analyzed after adoptive transfer experiments. A majority of minimally proliferated TEas in non-mAAQ host remained naïve (CD62LhighCD44int), demonstrating lack of activation. The proportion of naïve cells in this subset (72.08 ± 19.82%) was similar to the proportion before the experiment in fresh cells and the proportion in negative control hosts (C57BL/6). In the mAAQ+ host, in which no significant CFSE dilution was observed, 51.19 ± 37.34% shifted to an activated/intermediate phenotype (CD62Llow/CD44int). (C) The described phenomenon was statistically significant, demonstrating that a proportion of minimally proliferated indirect T cells in mAAQ+ hosts underwent activation, but its proliferation was controlled. (D) Computational analysis confirmed that 4C cells (semidirect pathway) proliferated in BDF1 (Left) and mAAQ+ hosts (Right). In a non-mAAQ host (D, Center) the cells remained in the first CFSE peak, showing no division cycles. (E) Activation status analysis was performed in 4C experiments. It was found that the majority of minimally proliferated cells in the negative control, non-mAAQ, and mAAQ+ hosts remained naïve, suggesting that no abortive activation phenomenon was associated with the semidirect/direct pathway response. Boxes show median, and whiskers show maximum and minimum.

In Vitro Analysis of Alloantigen Presentation—The PD-L1 Basis of Split Tolerance.

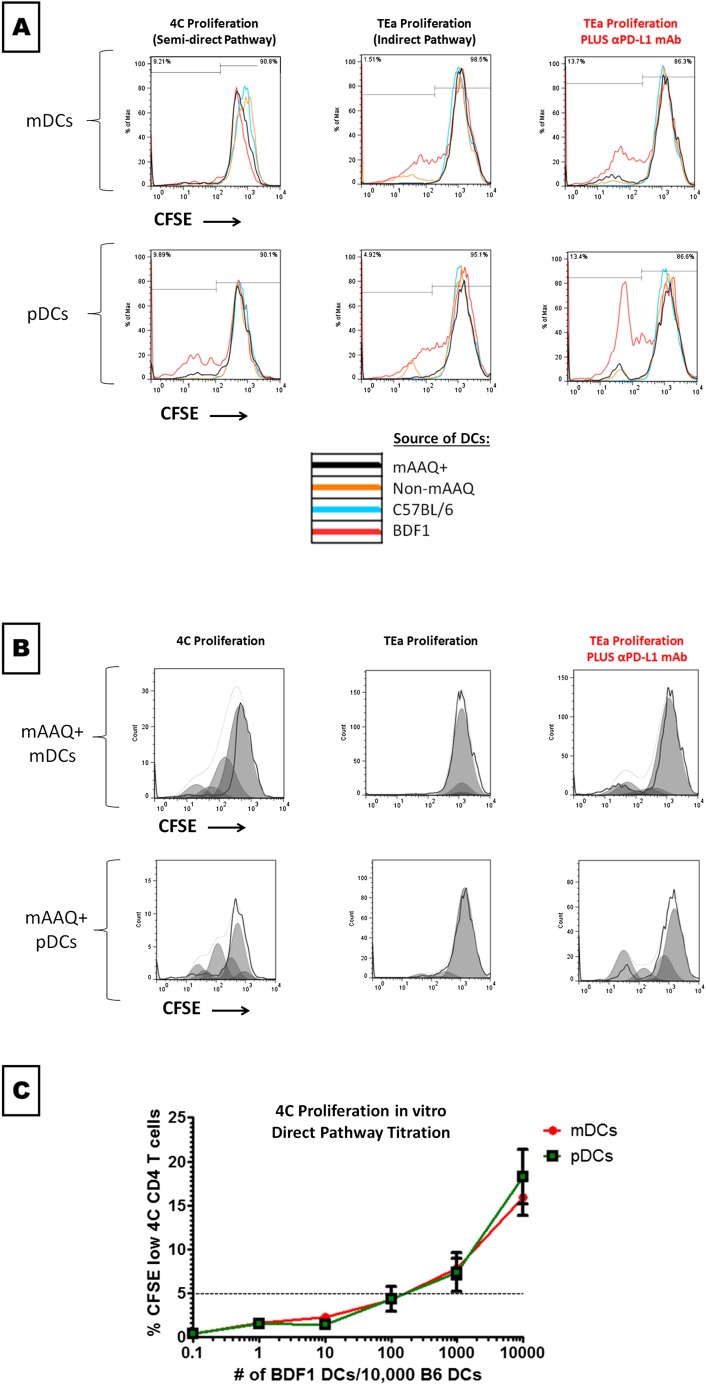

To determine whether the observed costimulatory/coinhibitory patterns on DCs were relevant to the mechanism of the split-tolerance condition, mDCs and pDCs were sorted from NIMAd mice and controls (C57BL/6 or BDF1) and cultured with either 4C or TEa cells, in the presence or absence of anti–PD-L1 antibody (Fig. 4F summarizes two independent experiments, two replicates each).

Whereas neither mDCs nor pDCs isolated from non-mAAQ mice stimulated proliferation of 4C T cells, both DC types induced TEa proliferation. The addition of anti–PD-L1 antibody to the TEa–non-mAAQ DC cultures had no effect on proliferation of the TEa cells.

In contrast, when mAAQ+ mice were used as the source of DCs for coculture, we observed opposite results, thus resembling the in vivo assay (Fig. 4 A–E). The mDCs from mAAQ+ mice induced proliferation of cocultured 4C T cells. In contrast, neither DC subset in mAAQ+ mice was able to stimulate TEa proliferation. However, PD-L1 blockade restored TEa proliferation: the levels of CFSElow TEa cells observed in the presence of anti–PD-L1 antibody strongly supported the role of PD-L1 in anergy/abortive activation of indirect recognition in mAAQ+ settings (Fig. 4E and Fig. S8 A and B).

Fig. S8.

Examples of indirect and semidirect pathway functionality in vitro. The experimental setting and rationale is described in Fig. 5 and the text. (A) Both mDCs and pDCs from mAAQ+ mouse (black) induced proliferation of 4C T cells (semidirect pathway; Left), whereas the indirect response (TEa cells; Center) was not active. Opposite functionality was induced by non-mAAQ DCs (orange). Strikingly, PD-L1 blockade allowed mAAQ+ DCs from mAAQ+ mice to activate the indirect pathway (A, Right). No significant changes were observed after PD-L1 blockade in the non-mAAQ and C57BL/6 experiments (shown percentages correspond to mAAQ+ experiments). (B) Cell-cycle division analysis (FlowJo) of transgenic cells proliferation (4Cs and TEas) in the presence of mAAQ+ DCs is shown (corresponding to black lines in A). This computational algorithm confirms the CFSE dilution results described in A. Remarkably, no cell-division cycles were detected in TEa cells without, but up to three to four cycles with, PD-L1 blockade. (C) To see what was the optimal ratio of DC stimulator:4C T cell for eliciting optimal proliferation response in vitro, we titrated DCs from BDF1 mice into cultures of CFSE-labeled 4C T cells. Note that below a 1:100 BDF1:C57BL/6 ratio, no 4C proliferation occurred. At a 1:10 ratio, a proliferation level similar to that observed with mAAQ+ DCs occurred (n = 2 for each time point). Results of this titration experiment suggest that mAAQ+ DCs, ∼10% of which were cross-dressed with I-Ad, could be responsible for effective antigen presentation, rather than the rare maternal CD11c cells (frequency = 10−5).

Finally, titration experiments were performed with variable ratios of BDF1:C57BL6 DCs for both mDCs and pDCs. The 4C cells did not proliferate below a 1:100 BDF1:C57BL/6 DCs ratio (Fig. S8C). These results strongly suggest that 4C proliferation induced by DCs from mAAQ+ mice represents T-cell interaction with cross-dressed host DCs, rather than direct allorecognition of the rare maternal DCs themselves.

Discussion

Low numbers of maternal cells persist in the offspring of placental mammals after birth. How such rare cells go on to mediate a tolerogenic impact on later fetal survival in adult female hosts (3, 4) and on transplant survival in males and females (5, 6, 23, 24), while causing an increased tempo of acute rejection episodes (5), has been a major conundrum.

Proposed Model for Rare Cell Amplification and Split Tolerance in Microchimerism.

Fig. 5 shows two hypothetical forms of MMc that could explain our results. Both models assume that DCs acquire peptide/MHC-II complexes by two distinct mechanisms, represented by opposite sides of the dotted lines in Fig. 5. One is classical MHC-II antigen presentation: Engulfed and processed exogenous antigens are recognized as peptides by CD4 T cells in a MHC-II–restricted manner (right sides of lines). The other is nonclassical: cross-dressing or acquisition of EVs (such as exosomes) containing intact peptide/MHC complexes from another cell source. This latter form of antigen presentation has recently been shown to be the cause of acute rejection of allografts, by greatly amplifying the impact of donor passenger leukocytes (19, 20).

Fig. 5.

Proposed models for microchimerism and exosome-mediated split tolerance. Models of DC nonclassical (cross-dressing) and classical MHC-II pathways of allopresentation in mice having non-mAAQ (A) and mAAQ+ (B) forms of microchimerism. (A) In a non-mAAQ condition, MMc-derived soluble allo-MHC molecules (red) are classically processed and presented in a self–MHC-II–restricted manner, leading to active indirect pathway (TEa) cells, whereas scarcity of intact allo-MHCs makes direct recognition (4C) inactive. The exosomes are all derived from self-tissue–resident DC, with ample CD86 and low PD-L1 coexpression, reinforcing self-MHC–restricted alloreactivity (* indicates a membrane fusion process that may occur on contact or only after exosome internalization, with recycling of the fused patch to the cell surface). (B) In mAAQ+ settings, not only are soluble allo-MHCs released from MMc, but also exosomes, generating a “Janus-faced” DC. On the left, nonclassical side, exosome-acquired intact allo-MHCs are colocalized with acquired CD86 in microdomains that exclude PD-L1, leading to activation of direct T-cell clones (4C). On the right, exosome acquisition leads to reprogramming of the classical MHC II pathway (“?” indicates that exosome-associated miRNA effects on PD-L1 mRNA translation are postulated), such that PD-L1 is present in the microdomains expressing the allopeptide/self–MHC-II complexes, generating abortive activation/anergy of indirect T-cell clones (TEa; red X) via PD-1 and TcR microclustering.

In the non-mAAQ host (Fig. 5A), MMc is depicted as a tissue-resident, MHC-II+ cell capable of producing only a soluble form of the MHC-II alloantigen I-Ed (Fig. 1H). This I-E is processed and presented as Eα52–68/I-Ab complexes, leading to YAe expression by DCs. Engagement of peptide–MHC occurs in the context of CD80 or CD86, so a responding T cell can form productive TCR/CD28 signaling complexes (25). In this low MMc condition (Fig. S5A), EVs are produced by host-type DC (Fig. 5A, Upper), not by maternal cells. The YAe epitope is packaged in EVs with a high CD86:PD-L1 ratio (Fig. 2B). Thus, the cross-dressing pathway reinforces a positive costimulation context for the TEa responder cell. However, the 4C T cell is left unstimulated.

In contrast, in the mAAQ+ host, MMc produces both soluble and EV-associated antigens (Figs. 1H and 5B). DCs are known to generate EVs capable of inducing transplant tolerance (26), but other MHC-II+ cellular subsets cannot be ruled out as EV sources. However, one can distinguish tolerant from graft-rejecter NIMAd mice by MMc presence in CD11c and CD11b lineages (27), implicating a myeloid cell. Because EVs derived from rare maternal cells (H2-Kd+) had CD86, but lacked PD-L1 (Fig. 2B), we propose that CD86-rich microdomains containing cross-dressed allo-MHC are formed on the DC surface. This formation of CD86/allo-MHC–enriched microdomains allows productive TCR/CD28 complexes to form on the 4C CD4 T cells, causing their proliferation. Remarkably, other microdomains formed on the same host DCs become enriched in PD-L1 (Figs. 3 and 5B). Antigens presented in these regions would be likely to induce TcR signaling in microclusters with PD-1, abrogating effective stimulation (28). Because PD-L1 is not coming from protein expressed by the MMc-derived EVs (Fig. 2B), we suggest an alternative possibility (indicated by ? in Fig. 5B): that exosomal RNA causes a functional reprogramming of the MHC-II/classical presentation pathway. The result is that endogenous PD-L1 is expressed in the same microdomains as Eα53–68/I-Ab complexes at the DC surface. An example of miRNA-based regulation controlling PD-L1 expression in mDCs has recently been reported (29). The observation of a stronger signal for PD-L1 on the Western blot of YAe-enriched serum EV fraction from mAAQ+ mice (Fig. 2B) suggests that the nonclassical cross-dressing pathway (Fig. 5B, Upper Left) has also been altered, increasing the PD-L1/CD86 ratio and further colocalizing the YAe epitope with PD-L1 (Fig. 3). Formation of PD-L1–poor and PD-L1–rich microdomains on DCs, along with lower expression of Eα53–68/I-Ab complexes (Fig. 2B), could account for productive stimulation of 4C, but abortive activation and anergy of TEa cells (red X, Fig. 5B).

Split Tolerance and NIMA Effect.

One important caveat in our study is that only one mouse strain combination (B6 -H2b, DBA/2-H2d) has been analyzed. Thus, it is possible that an EV-based mechanism for rare signal amplification and differential costimulation of T effector cells, leading to split tolerance, applies only to this particular mouse breeding model. However, there is reason to believe that such a mechanism is widely applicable. In a different mouse breeding combination, Akiyama et al. (30) showed that directly alloreactive CD8 TcR Tg T cells were not inhibited by NIMA class I exposure; instead, Kb-exposed H2k mice were tolerized at the level of allopeptide-specific CD4 Th cells, consistent with split tolerance (30).

The finding of Kinder et al. (4), that MMc-induced Treg development impacts cross-generational reproductive fitness via NIMA-specific Tregs in female offspring, appears to conflict with the results of Molitor-Dart et al. (24) showing increased likelihood of acute rejection in female vs. male recipients of NIMA+ heart allografts. However, a higher level of MMc in females, and the presence of intrauterine MMc in particular (4), may enhance development of allopeptide-specific Tregs, but at a cost of a stronger semidirect pathway, responsible for a higher acute rejection risk in an immunosuppressive-free model of organ transplantation (24). Indeed, mammalian pregnancy requires an acute inflammatory response to facilitate embryo implantation, while chronic regulation of the maternal immune response during gestation protects against fetal loss (31). In this way, split tolerance to NIMA may be the best way to enforce cross-generational fitness (4).

Our results, together with those of Kinder et al. (4), help to explain the original observations of split tolerance to NIMA-Rh by Owen et al. (3). Indeed, the claim leveled against Owen’s hypothesis was that, rather than tolerizing the daughter to a subsequent fetal antigen, NIMA exposure had sensitized her (32). This apparent contradiction may now finally be resolved, because, at the cell surface of the MMc-modified, mAAQ+ DCs, both sensitizing and tolerizing forms of NIMA presentation can be found side by side. The contrasting impact of functional, CD86-associated, and nonfunctional, PD-L1–associated, microdomains may explain why host B-cell responses were historically the first to be described as suppressed by exposure to maternal noninherited antigens, because IgG responses such as those to Rh (3) or HLA (33) are strictly dependent on Th cells, triggered by the classical pathway of peptide/MHC-II generation and antigen presentation (34). Our findings may be relevant to other contexts: for example, the antileukemia effect of cord blood transplants when the recipient is mismatched for a NIMA (35) or shares an IPA (36) and the breaking of split tolerance to tumor antigens by PD1/PD-L1 blockade (37).

Materials and Methods

Mice.

The 8- to 12-wk-old C57BL/6, BDF1 (Harlan), TEa TCR Tg [B6.Cg-Tg(Tcra,Tcrb)3Ayr/J; Jax catalog no. 005655], 4C TCR Tg (Duke University), and C57BL/6 CD90.1 (B6.PL-Thy1a/CyJ; Jax catalog no. 000406) mice were used. All studies with mice were performed in accordance with NIH vertebrate animals guidelines, and approved by the University of Wisconsin–Madison Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Serum EV Enrichment.

An exosome-isolation kit (Invitrogen, catalog no. 4478360) was used for serum EV enrichment, plus final ultrafiltration (0.45 μm). In experiments for ELISA analysis, the ultrafiltration method was used (SI Materials and Methods).

Flow Cytometry Imaging (ImageStream).

Antibodies and procedures for flow cytometry imaging are listed in SI Materials and Methods. Acquisition was made with BD LSR-II and ImageStream MKII Amnis (60×). Data analysis was performed by using FlowJo (Version 7.6.5 or 10) and Ideas.

Surgical Procedures.

Hemisplenectomies and heterotopic heart transplants were performed as described in Dutta et al. (9).

Cell Sorting.

For cell sorting, magnetic beads technology was used (Miltenyi and StemCell Technologies, QuadraMACS and PurpleMagnet).

Adoptive Transfer Experiments (in Vivo MLR).

Hemisplenectomy was performed in mice, and splenocytes used to determine mAAQ status. Seven days later, mice were i.v.-injected (retroorbital) with 10–15 × 106 CFSE-labeled TCR Tg CD4 T cells. At 72 h after the injection, TCR Tg cell proliferation was addressed with the CFSE-dilution method (splenocytes).

TCR Tg CD4 T Cell Proliferation in Vitro.

CFSE-labeled TCR Tg CD4 T cells were cultured in vitro with either mDCs or pDCs from different sources. The T-cell/DC ratio was 20/1, in complete medium + 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated FBS for 84 h at 37 °C. For PD-L1 blockade experiments, a concentration of 0.20 µg/mL was added.

Microchimerism Analysis-qPCR.

qPCR with HDd primers were performed as described in ref. 23, and the number of copies was estimated based on Cq values.

Antigen Acquisition in Vitro Cell Culture with EVs.

Splenocytes were cultured with EVs. A total of 0.5 × 106 splenocytes + standardized amount of EV (50 μg of total EV-derived proteins) in Complete medium + 10% exosome-free FBS (SBI SystemBiosciences, no. EXO-FBS-50A-1) were cultured at 37 °C.

Western Blot and ELISA.

Western blots and ELISAs were performed by following standard procedures (see details in SI Materials and Methods).

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical significance was estimated by using Student’s t, the Mann–Whitney U test, χ2, and Pearson r, when appropriate, with α = 0.05.

SI Materials and Methods

Mice.

C57BL/6 and BDF1 mice were purchased from Harlan. TEa TCR Tg mice [B6.Cg-Tg(Tcra,Tcrb)3Ayr/J] were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (catalog no. 005655). The 4C TCR Tg mice were described (38). Both TCR Tg colonies were established breeding TCR Tg males with congenic C57BL/6 CD90.1 (B6.PL-Thy1a/CyJ) females purchased from Jackson Laboratories (catalog no. 000406). TEa rearrangement is defined by coexpression of Vα2 and Vβ6, and 4C TCR by Vβ13 expression. NIMAd mice were obtained by backcrossing BDF1 females with C57BL/6 males. Animals were used for experiments at 8–12 wk old, having been breastfed until 3 wk of age. Females and males were used for population analysis of mAAQ, whereas only males where used for further experiments.

Serum EV Enrichment and Characterization.

EV-enriched fraction was obtained from serum. In experiments where the purpose was to obtain EV-enriched vs. EV-free serum fractions for ELISA analysis (Fig. 4D), we performed 2× centrifugations for 30 min at 10,000 × g and collected the supernatant, followed by a further ultracentrifugation step, for 2 h at 100,000 × g. The latter pellet was suspended in PBS (pH 7.2). In all other cases, an exosome-isolation kit was used (Invitrogen; catalog no. 4478360). Proteinase K treatment was not performed. We introduced two extra steps: centrifugation of the exosome preparation at 10,000 × g for 2 min, then filtration (0.45 μm). Protein concentration in the preparation was used as an indirect measurement of the exosome content and was performed by using a nanodrop spectrophotometer (280 nm). We also used transmission electron microscopy to characterize EV sizes more precisely (see below).

Flow Cytometry Abs.

Fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal Abs were used at proper concentrations according to vendor or titration experiments in our laboratory. Abs/fluorochromes are listed below. CFSE labeling was performed by mixing 20 × 106 cells per milliliter at a CFSE final concentration = 10 μM, and then incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. Acquisition was made with BD LSR-II (five lasers). Data analysis was performed by using FlowJo (Version 7.6.5 or 10).

Abs with the following specificities were used for flow cytometry (clones are listed in parentheses): YAe (eBio-YAe), H2Kd (SF1-1.1.1), IAd (AMS-32.1), IAb (AF6-120.1), CD11c (N418), CD11b (M1/70), B220 (RA3-6B2), PD-L1 (MIH5), CD80 (16-10A1), CD86 (GL1), ICOSL (HK5.3), CD40 (2/23), CD3 (145-2C11), CD4 (RM4-5), Foxp3 (FJK-16s), CD25 (PC61), Ki67 (SolA15), CD90.1 (OX-7), Vα2 (B20.1), Vβ6 (RR4-7), Vβ13 (MR12-3), CD44 (IM7), CD62L (MEL-14), TGFβ/LAP (TW7-16B4), and CD9 (MZ3). Fc blocking was done with TruStain (αCD16/32; Biolegend catalog no. 101320). Depending on the panel, the following fluorochromes were used: FITC, PerCP, PerCP-eFluor 710, PE, Pacific Blue, BV421, eFluor 450, APC, APC-Cy7, and APC eF780. Antibodies were purchased from eBioscience, BD Bioscience, or Biolegend.

Immunophenotypes.

Immunophenotypes were as follows: Mouse: mDCs (CD11c+B220neg), pDCs (CD11c+B220+), monocytes/macrophages (CD11b+CD11cneg), B cells (B220+CD3negCD11cneg), and T cells (CD3+B220neg). Fig. S1 for details and flow cytometry gating strategy.

Imaging Flow Cytometry (ImageStream).

Immunostaining of human and mouse samples was performed in the same way described for flow cytometry. A Two-lasers ImageStream Amnis device was used (60×). All analyses, including BSI, were performed by using the software Ideas (Version 6.0).

Cell Sorting.

CD4 T cells were sorted by negative selection in two steps: (i) whole T-cell population (PanT cell Isolation kit II; Miltenyi, catalog no. 130-095-130); and (ii) CD4 T cells negatively selected (CD8 microbeads; Miltenyi, catalog no. 130-049-401). Either AutoMACS or QuadroMACS was used. In every case, purity ranged between 90% and 95%. In the case of TCR Tg cells (TEa and 4C), 80–85% of fresh cells showed a nonactivated phenotype (CD62LhighCD44low).

Whole DCs were sorted by negative selection (Mouse Pan-DC Enrichment Kit; StemCell Technologies, catalog no. 19763) and the PurpleEasysep Magnet. Then, B220 microbeads (Miltenyi, catalog no. 130-049-501) were used to obtain mDCs in the negative fraction and pDCs in the positive one (in this step, QuadroMACS were used). Purity ranged between 65% and 70%.

Adoptive Transfer Experiments (in Vivo MLR).

Hemisplenectomy was performed in mice, and splenocytes were used to determine mAAQ status. Seven days later, mice were IV injected (retroorbital) with 10–15 × 106 CFSE-labeled TCR Tg CD4 T cells (either TEa or 4C). At 72 h after the injection, mice were killed. TCR Tg cell proliferation was addressed with the CFSE-dilution method (splenocytes). Division-cycling analysis (FlowJo) was used as a complementary readout.

TCR Tg CD4 T Cells Proliferation in Vitro.

CFSE-labeled TCR Tg CD4 T cells (TEa or 4C) were cultured in vitro with either mDCs or pDCs from different sources. The T-cell/DC ratio was 20/1. A 96-well plate was used, and 200,000 CD4 T cells + 10,000 DCs (either myeloid or plasmacytoid)/200 μL of complete medium + 10% heat-inactivated FBS per well were cultured for 84 h (3.5 d) at 37 °C. Duplicates were made for each source of DCs. For PD-L1 blockade experiments, the conditions were identical, but 2 μL of hamster αPD-L1 per well was added (10 μL/mL = 20 µg/mL). Hamster anti–PD-L1 Ab was provided by Douglas McNeel, University of Wisconsin–Madison. Titration experiments were performed under identical conditions, keeping the T-cell/DC ratio constant (20/1). Within the DCs, the proportion of BDF1/C57BL6 was titrated as follows: 1/10,000; 1/1,000; 1/100; 1/10; and 10,000/1.

qPCR.

DNA extraction was made following the recommendations by the Qiagen Mini Blood Kit. H2Dd forward primer (CCTTCCCAGAGCCTCCTTCA), H2Dd reverse primer (AGAACTCAGACCCTGCCCTTTAA), and probe (TCCACCAAGACTAACACAGTAATCATTGCTGTTCC-BHQ) were purchased from the Biotechnology Center, University of Wisconsin–Madison. Estimated numbers of copies were based on a linear curve fit of end point relative fluorescence from a dilution series (Cq values) as described (23).

CFSE Validation.

CFSE dilution method as a readout of T-cell proliferation was validated by performing in vivo and in vitro experiments with TEa CD4 T cells and 4C CD4 T cells. A strong inverse correlation was found between CFSE fluorescence and Ki-67 signal on flow cytometry.

Transmission Electron Microscope Analysis of Whole-Mounted EVs.

Serum was collected from whole blood, and exosomes were extracted by using the Invitrogen isolation kit. The exosome fraction was then resuspended in 100 μL of 1× PBS. A total of 20 μL of this EV-enriched suspension was then ultracentrifuged at 100,000 × g for 2 h at 4 °C. The EV-enriched pellet was resuspended in 2 μL of 1× PBS and deposited on a Formvar-carbon on 300 mesh Cu transmission electron microscopy grid. After air-drying, the grid was fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde overnight at 4 °C and then stained with 7.7% aqueous uranyl acetate for 5 min at 60 °C. The grid was then rinsed with three changes of distilled water, followed by 1-min stain with Reynold’s lead citrate and again rinsed with three changes of distilled water. The grid was dried with filter paper and scoped on a Hitachi H7650 transmission electron microscope.

Induction of Allotolerance in Mice Before Heart Transplant.

On day 0, C57BL/6 mice received a heterotopic heart transplant from a fully allogeneic DBA/2 donor. Also on day 0, they received 125 μg of hamster anti-CD40L Ab (MR1) i.p. MR1 treatment was repeated on days 2 and 4. MR1 was purchased from BioXcell.

Western Blot.

From the EV preparation, a volume equivalent to 20 μg of protein, to which was added 3 volumes of lysis buffer, was incubated for 10–15 min at room temperature. We then added 1/5 of total volume of 5× loading buffer and 1/10 total volume of 2-mercaptoethanol, adding ddH2O up to 40 μL.

After incubating the mix for 5 min at 100 °C, samples were loaded on the polyacrylamide gel and run at 200 V for 40 min. After transfer to blotting paper for 45 min at 100 V, we checked protein presence with Ponceau S, then rinsed blots in PBS–Tween (3×), blocking for 1–2 h in PBS–Tween with 5% powdered milk at room temperature (RT) or overnight at 4 °C. After adding a 1/1,000 dilution of anti–PD-L1 (gift from Douglas McNeel), anti-CD86 (Abcam), anti-gp96 (ThermoFisher), anti-GM130 (Abcam), anti-Histone H4 (ThermoFisher), anti-Calnexin, or anti-CD9 (both Abcam) in PBS-Tween with 5% milk, and incubation overnight at 4 °C, a 1/3,000 dilution of 2° anti-rabbit IgG was added in PBS-Tween with 5% milk at RT for 1 h.

ELISA.

Levels of I-E were determined by ELISA. The 96-well ELISA plates (Costar) were coated overnight at 4 °C with 10 μg/mL monoclonal anti-mouse I-E (clone 14-4-4S) in Tris buffer. Wells were blocked for 1 h at 4 °C with 2% BSA in PBS, followed by incubation with diluted standards and samples (25 μL per well). Rat anti–I-A/I-E (clone M5/114.15.2; eBioscience) was used as the detection Ab at a concentration of 10 μg/mL. HRP-conjugated goat anti-rat (eBioscience) was then added, followed by TMB substrate for 30 min at RT. Each incubation step was for 1 h at RT, followed by four washing steps in 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS and two washes in PBS. The reaction was stopped by adding 2 M H2SO4. Antigens from a BDF1 spleen cell lysate were used as a standard; the dilution on the linear portion of the standard curve that gave the highest signal over background at a 450-nm wavelength was defined as 1 unit of I-E antigen per milliliter. I-E levels were determined on an ELISA plate reader as a fraction of this standard.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical significance of difference of means between groups was estimated by using the Mann–Whitney U test (after Shapiro–Wilks analysis of Gaussian distribution). Contingency analysis was estimated by using χ2. Correlation between numerical variables was estimated by using Pearson’s r. In every case, statistical significance was reached for P < 0.05. Calculations and graphics were made with GraphPad Prism (Version 6.0).

Acknowledgments

We thank the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital Electron Microscopy Facility for EM assistance; Drs. Gilles Benichou, Jeremy Sullivan, and Dixon Kaufman for helpful suggestions on the manuscript; Dr. Luis Queiroz, Dr. John Verstegen (MOFA-Madison), and the personnel of the UW Carbone Cancer Center Flow Laboratory (University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA014520) for the technical support on flow cytometry and ImageStream experiments; and Dr. Douglas McNeel for providing the anti–PD-L1 antibody. This project was supported by NIH Grant 2R01-AI066219 (to W.J.B.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1618364114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Owen RD. Immunogenetic consequences of vascular anastomoses between bovine twins. Science. 1945;102(2651):400–401. doi: 10.1126/science.102.2651.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scandling JD, et al. Tolerance and withdrawal of immunosuppressive drugs in patients given kidney and hematopoietic cell transplants. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(5):1133–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.03992.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Owen RD, Wood HR, Foord AG, Sturgeon P, Baldwin LG. Evidence for actively acquired tolerance to Rh antigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1954;40(6):420–424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.40.6.420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinder JM, et al. Cross-generational reproductive fitness enforced by microchimeric maternal cells. Cell. 2015;162(3):505–515. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burlingham WJ, et al. The effect of tolerance to noninherited maternal HLA antigens on the survival of renal transplants from sibling donors. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(23):1657–1664. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812033392302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Rood JJ, et al. Effect of tolerance to noninherited maternal antigens on the occurrence of graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation from a parent or an HLA-haploidentical sibling. Blood. 2002;99(5):1572–1577. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.5.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benichou G, et al. Immunogenicity and tolerogenicity of self-major histocompatibility complex peptides. J Exp Med. 1990;172(5):1341–1346. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.5.1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jankowska-Gan E, et al. Pretransplant immune regulation predicts allograft outcome: Bidirectional regulation correlates with excellent renal transplant function in living-related donor-recipient pairs. Transplantation. 2012;93(3):283–290. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31823e46a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dutta P, Dart M, Roenneburg DA, Torrealba JR, Burlingham WJ. Pretransplant immune-regulation predicts allograft tolerance. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(6):1296–1301. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03484.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dutta P, Burlingham WJ. Tolerance to noninherited maternal antigens in mice and humans. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2009;14(4):439–447. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32832d6683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roelen DL, van Bree FP, van Beelen E, van Rood JJ, Claas FH. No evidence of an influence of the noninherited maternal HLA antigens on the alloreactive T cell repertoire in healthy individuals. Transplantation. 1995;59(12):1728–1733. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199506270-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hadley GA, Phelan D, Duffy BF, Mohanakumar T. Lack of T-cell tolerance of noninherited maternal HLA antigens in normal humans. Hum Immunol. 1990;28(4):373–381. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(90)90032-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benichou G, Thomson AW. Direct versus indirect allorecognition pathways: On the right track. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(4):655–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ten Wolde S, et al. Influence of non-inherited maternal HLA antigens on occurrence of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 1993;341(8839):200–202. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90065-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feitsma AL, et al. Protective effect of noninherited maternal HLA-DR antigens on rheumatoid arthritis development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(50):19966–19970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710260104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrera OB, et al. A novel pathway of alloantigen presentation by dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2004;173(8):4828–4837. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.4828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wakim LM, Bevan MJ. Cross-dressed dendritic cells drive memory CD8+ T-cell activation after viral infection. Nature. 2011;471(7340):629–632. doi: 10.1038/nature09863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sivaganesh S, et al. Copresentation of intact and processed MHC alloantigen by recipient dendritic cells enables delivery of linked help to alloreactive CD8 T cells by indirect-pathway CD4 T cells. J Immunol. 2013;190(11):5829–5838. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marino J, et al. Donor exosomes rather than passenger leukocytes initiate alloreactive T cell responses after transplantation. Sci Immunol. 2016;1(1):1–10. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaf8759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Q, et al. Donor dendritic cell-derived exosomes promote allograft-targeting immune response. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(8):2805–2820. doi: 10.1172/JCI84577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robbins PD, Morelli AE. Regulation of immune responses by extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(3):195–208. doi: 10.1038/nri3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andrassy J, et al. Tolerance to noninherited maternal MHC antigens in mice. J Immunol. 2003;171(10):5554–5561. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dutta P, et al. Microchimerism is strongly correlated with tolerance to noninherited maternal antigens in mice. Blood. 2009;114(17):3578–3587. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-213561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Molitor-Dart ML, Andrassy J, Haynes LD, Burlingham WJ. Tolerance induction or sensitization in mice exposed to noninherited maternal antigens (NIMA) Am J Transplant. 2008;8(11):2307–2315. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yokosuka T, et al. Spatiotemporal regulation of T cell costimulation by TCR-CD28 microclusters and protein kinase C theta translocation. Immunity. 2008;29(4):589–601. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pêche H, et al. Induction of tolerance by exosomes and short-term immunosuppression in a fully MHC-mismatched rat cardiac allograft model. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(7):1541–1550. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dutta P, Burlingham WJ. Correlation between post transplant maternal microchimerism and tolerance across MHC barriers in mice. Chimerism. 2011;2(3):78–83. doi: 10.4161/chim.2.3.18083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yokosuka T, et al. Programmed cell death 1 forms negative costimulatory microclusters that directly inhibit T cell receptor signaling by recruiting phosphatase SHP2. J Exp Med. 2012;209(6):1201–1217. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ifergan I, Chen S, Zhang B, Miller SD. Cutting edge: MicroRNA-223 regulates myeloid dendritic cell-driven Th17 responses in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2016;196(4):1455–1459. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akiyama Y, et al. Transplantation tolerance to a single noninherited MHC class I maternal alloantigen studied in a TCR-transgenic mouse model. J Immunol. 2011;186(3):1442–1449. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dekel N, Gnainsky Y, Granot I, Racicot K, Mor G. The role of inflammation for a successful implantation. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;72(2):141–147. doi: 10.1111/aji.12266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor JF. Sensitization of Rh-negative daughters by their Rh-positive mothers. N Engl J Med. 1967;276(10):547–551. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196703092761004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Claas FH, Gijbels Y, van der Velden-de Munck J, van Rood JJ. Induction of B cell unresponsiveness to noninherited maternal HLA antigens during fetal life. Science. 1988;241(4874):1815–1817. doi: 10.1126/science.3051377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steele DJR, et al. Two levels of help for B cell alloantibody production. J Exp Med. 1996;183(2):699–703. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.2.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Rood JJ, et al. Reexposure of cord blood to noninherited maternal HLA antigens improves transplant outcome in hematological malignancies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(47):19952–19957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910310106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Rood JJ, Scaradavou A, Stevens CE. Indirect evidence that maternal microchimerism in cord blood mediates a graft-versus-leukemia effect in cord blood transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(7):2509–2514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119541109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herbst RS, et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature. 2014;515(7528):563–567. doi: 10.1038/nature14011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brennan TV, et al. A new T-cell receptor transgenic model of the CD4+ direct pathway: Level of priming determines acute versus chronic rejection. Transplantation. 2008;85(2):247–255. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31815e883e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]