Abstract

This study examined self-discrepancy, a construct of theoretical relevance to eating disorder (ED) psychopathology, across different types of EDs. Individuals with anorexia nervosa (AN; n = 112), bulimia nervosa (BN; n = 72), and binge eating disorder (BED; n = 199) completed semi-structured interviews assessing specific types of self-discrepancies. Results revealed that actual:ideal (A:I) discrepancy was positively associated with AN, actual:ought (A:O) discrepancy was positively associated with BN and BED, and self-discrepancies did not differentiate BN from BED. Across diagnoses, A:O discrepancy was positively associated with severity of purging, binge eating, and global ED psychopathology. Further, there were significant interactions between diagnosis and A:O discrepancy for global ED psychopathology and between diagnosis and A:I discrepancy for binge eating and driven exercise. These results support the importance of self-discrepancy as a potential causal and maintenance variable in EDs that differentiates among different types of EDs and symptom severity.

Keywords: Self-discrepancy, eating disorders, bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa, binge eating disorder

Self-discrepancy, a construct which refers to the extent to which a person believes there is a discrepancy between their actual self and other self-guides (i.e., personal standards), has been identified in causal, maintenance, and treatment models of various forms of psychopathology (Higgins, 1989). Higgins first described the role of self-discrepancies in psychopathology in his self-discrepancy theory, which posits that individuals compare themselves to a number of self-guides including their actual self, ideal self, and ought self. These self-guides are not inherently adaptive or maladaptive per se, but rather it is the relation and discrepancy between the self-guides and the perceived actual self that lead to emotional vulnerability and psychopathology. More recently, self-discrepancy has been identified in models of eating disorder (ED) psychopathology. For example, the integrative cognitive-affective therapy (ICAT) model of bulimia nervosa (BN) suggests that self-discrepancies have an important role in the onset and maintenance of eating disorders (EDs; Wonderlich, Peterson, & Smith, 2015). More specifically, the ICAT model suggests that self-discrepancies are associated with the use of ED behaviors as a way to pursue ideal or ought standards (Wonderlich et al., 2008). Those with high self-discrepancies may feel worse about their weight and shape due to not meeting ideal and ought standards, which is associated with emotion regulation deficits as well as momentary negative affect (Heron & Smyth, 2013).

Two forms of self-discrepancy that have been frequently studied are actual:ideal [A:I] discrepancy, which refers to a discrepancy between who one is and who one ideally would like to be, and actual:ought [A:O] discrepancy, which refers to a discrepancy between who one is and who one ought to be (or must be). A:I discrepancy is characterized by the absence of positive outcomes and dejection-related emotions such as depression, whereas A:O discrepancy is characterized by the presence of negative outcomes and agitation-related emotions such as anxiety (Higgins, 1989). Consistent with ICAT and self-discrepancy theory, self-discrepancies have been found to be associated with disordered eating and body dissatisfaction (Strauman, Vookles, Berenstein, Chaiken, & Higgins, 1991). Specifically, Strauman and colleagues found that symptoms related to BN were associated with unfulfilled positive potential (a form of A:I discrepancy) and symptoms associated with AN were related to A:O discrepancy in a sample of college students. A:I discrepancy, specifically, has been linked to body size overestimation as well (Strauman & Glenberg, 1994). Further, Wonderlich et al. (2008) found that both A:I and A:O discrepancies were elevated in those with BN versus controls. However, Sawdon, Cooper, & Seabrook (2007) found no significant correlations between ED symptoms (measured using the Eating Attitudes Test) and A:I or A:O among a community sample of 100 women.

Despite the potential salience of self-discrepancies in ED psychopathology and the potential overlap with other constructs that have been widely investigated in ED research (e.g., perfectionism, self-esteem), findings regarding the extent to which self-discrepancies vary by ED diagnosis and symptom severity are limited. Thus, the purpose of the current study was to examine the degree of self-discrepancies across the three primary ED diagnoses (i.e., anorexia nervosa [AN], BN, and binge eating disorder [BED]). In addition, we investigated how self-discrepancies were uniquely associated with ED symptoms (i.e., global ED psychopathology, objective binge eating, purging, and driven exercise), as well as how these associations differed by ED diagnosis. Due to the limited knowledge of self-discrepancies across ED categories, there were no a priori hypotheses.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The overall sample in the current investigation was comprised of participants who were enrolled in one of three separate ED research studies (e.g., AN: Engel et al., 2013; BN: Wonderlich et al., 2014; BED: Peterson, Mitchell, Crow, Crosby, & Wonderlich, 2009). Only women were included in the study as there was a low percentage of males across studies. Also, participants with missing values for self-discrepancies were removed. Participants from the three studies were merged into a final sample which included 383 women: 112 with AN, 72 with BN, and 199 with BED. Details on each sample and relevant procedures for the corresponding study are described below. Relevant institutional review boards approved each of the individual study protocols and written informed consent was provided by all participants.

AN sample

Women with AN were recruited at one of three sites in the Midwestern United States. The mean age was 25.1 ± 8.4 years and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 17.2 ± 1.0 kg/m2. Those who met preliminary criteria based on an initial phone screen attended two study visits to complete structured interviews. Eligibility criteria including being female, at least 18 years of age, and meeting criteria for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th Edition: DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) AN or subthreshold AN. Subthreshold AN criteria for the study were defined as meeting all of the DSM-IV criteria for AN except: (1) body mass index was between 17.5 and 18.5, or (2) absence of amenorrhea or an absence of the cognitive features of AN (i.e., no fear of fat or overvaluation of shape/weight). Exclusion criteria included: pregnancy/lactation, history of bariatric surgery, current inpatient hospitalization, current substance use disorder, medical or psychiatric instability, and current psychotherapy.

BN sample

Treatment-seeking adults with BN were recruited from two sites in the Midwestern United States. The mean age was 27.6 ± 10.0 years and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 23.9 ± 5.5 kg/m2. Participants were classified as either (a) full threshold BN according to DSM-IV or (b) subthreshold BN (i.e., experiencing compensatory behaviors accompanying subjective bulimic episodes at least weekly for 3 months before enrollment, or meeting BN criteria except for binge eating on average once per week). Exclusion criteria included: pregnancy/lactation, BMI <18 kg/m2, lifetime bipolar or psychotic disorder diagnosis, current substance use disorder, medical or psychiatric instability, and current psychotherapy.

BED sample

Treatment-seeking adults with BED were recruited in the Midwestern United States. The mean age was 46.7 ± 10.3 years and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 39.0 ± 7.8 kg/m2. Inclusion criteria were meeting full criteria for DSM-IV BED and a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy or lactation; lifetime diagnosis of bipolar or psychotic disorder; current diagnosis of substance abuse or substance dependence; medical or psychiatric instability including acute suicide risk; current psychotherapy; or current participation in a formal weight loss program.

Measures

SELVES Interview (adapted from Higgins et al., 1986)

The SELVES Interview is a direct adaptation of the original Selves Questionnaire, which measures self-discrepancy by assessing each participant’s self-described actual-self, ideal-self, and ought-self attributes. That is, the SELVES obtains an assessment of participants’ beliefs regarding their current behaviors/attributes as well as self-guides, which may be conceptualized as personal standards. Participants were asked to generate lists of attributes that describe the kind of person they believe they actually are (i.e., actual self), the type of person they would ideally like to be (i.e., ideal self), and the kind of person they believe they ought to, or must be (i.e., ought self). Common responses to the ideal and ought questions included both appearance (e.g., “attractive”) and non-appearance-focused (e.g., “successful,” “loving,” “hard-working,” “kind,”) descriptors. Interviewers were trained to elicit at least six or more attributes/traits for each list from participants. Each self-discrepancy score is a weighted difference score comparing the number of actual-self/self-guide “matches” (e.g., actual-self: “friendly,” ideal-self “friendly”) with the number of actual-self/self-guide “mismatches” (e.g., actual-self: “lazy”, ought-self “hard-working”).

The scoring of the SELVES required several steps. First, for actual, ideal, and ought self-guides, any redundant and contradictory words that followed the original word in each particular list were removed. Second, the list of actual self-guides were compared to the list of ideal and ought self-guides. Raters coded each pair of words as either a match, a mismatch of extent, a mismatch, and a non-match. A match was defined as pairs of words that were the same or similar and were given a score of −1. A mismatch was defined as pairs of words that were opposite and were given a score of +2. A mismatch of extent was defined as pairs of words that were the same or similar but included a qualifier (e.g., actual = beautiful vs. ideal = very beautiful) and were given a score of +1. A non-match was defined as a pair of words that were neither similar nor opposing and were given a score of 0.

Each self-discrepancy score is a weighted difference score comparing the number of actual-self/self-guide “matches” (e.g., actual-self: “friendly,” ideal-self “friendly”) with the number of actual-self/self-guide “mismatches” (e.g., actual-self: “lazy”, ought-self “hard-working”). Non-matches were not included in the calculation of self-discrepancy scores. A:I discrepancy was a score comparing actual self and ideal self words and A:O discrepancy was a score comparing actual self and ought self words. This scoring procedure has been shown to be valid (Higgins et al., 2009). Scores could range from negative to positive, with higher positive scores meaning more self-discrepancy and lower negative scores meaning lower self-discrepancy.

Eating Disorder Examination (EDE; Fairburn et al., 2008)

The EDE interview assesses global ED psychopathology consisting of restraint, eating concerns, shape concerns, and weight concerns. In addition, individuals reported the frequency of objective binge eating, laxative use, and vomiting that occurred in the past 28 days as well as the number of days of driven exercise. Laxative use and vomiting were combined to create a purging variable. Inter-rater reliability ratings for EDE global, conducted on a random sample of audiotaped interviews, were greater than .80 (intraclass correlation coefficients) in all samples.

Statistical Analyses

Three logistic regressions were calculated to examine A:I and A:O self-discrepancies as predictors of ED diagnoses (i.e., AN vs. BN, AN vs. BED, and BN vs. BED). A:I and A:O were entered simultaneously as predictors in each logistic regression model with ED diagnosis as the outcome. Four linear and negative binomial generalized linear models (depending upon the distribution of the outcome) were used to examine ED diagnosis, self-discrepancies, and their interaction in relation to ED symptom variables (i.e., global ED psychopathology, objective binge eating, purging, and driven exercise). ED diagnosis, self-discrepancies, and their interaction were the independent variables and global ED psychopathology, objective binge eating, purging, and driven exercise were the outcome variables.

Results

Mean A:I discrepancy for the diagnostic groups was −0.30 ± .17 (AN), −0.43 ± .31 (BN), and −0.83 ± .15 (BED). Mean A:O discrepancy for the diagnostic groups was −1.12 ± .14 (AN), −0.46 ± .23 (BN), and −0.92 ± .12 (BED). Logistic regressions predicting ED diagnosis based on self-discrepancies (see Table 1) revealed that A:I discrepancy was associated with greater likelihood of AN compared to BN and BED, and A:O discrepancy was associated with greater likelihood of BN and BED compared to AN. Self-discrepancies did not differentiate BN from BED. Table 2 presents the results of generalized linear models testing the association of diagnosis, self-discrepancies, and their interactions with ED psychopathology. Across diagnoses, higher A:O discrepancy was associated with greater objective binge eating, purging, and global ED psychopathology and higher A:I discrepancy was associated with a lower frequency of binge eating.

Table 1.

Logistic Regressions of Diagnostic Group and Self-Discrepancies

| ANa vs. BN | ANa vs. BED | BNa vs. BED | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | OR | 95% CI | B | SE | OR | 95% CI | B | SE | OR | 95% CI | |

| A:I Discrepancy | −.17 | .09 | .84* | [.71, .99] | −.21 | .07 | .82* | [.71, .93] | −.03 | .08 | .97 | [.83, 1.12] |

| A:O Discrepancy | .34 | .11 | 1.41* | [1.14, 1.74] | .21 | .09 | 1.23* | [1.04, 1.45] | −.14 | .10 | .87 | [.72, 1.05] |

Note:

Reference group;

p < .05

Table 2.

General Linear Models of Diagnostic Group, Self-Discrepancies, and Interactions

| Global | Binge Eating | Purging | Driven Exercise | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | P | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | |

| Dx = BN | 0.38 | .18 | .03 | 1.75 | .18 | < .001 | 1.05 | .12 | < .001 | −.32 | .18 | .08 |

| Dx = BED | −0.31 | .15 | .04 | 1.73 | .16 | <.001 | −5.83 | .17 | <.001 | −2.10 | .17 | <.001 |

| Dx = AN | 0 | - | - | 0 | - | - | 0 | - | - | 0 | - | - |

| A:I | −.02 | .06 | .79 | −.29 | .07 | <.001 | .01 | .07 | .92 | 0.10 | 0.06 | .09 |

| A:O | .20 | .08 | .007 | .19 | .08 | .01 | .20 | .07 | .004 | −.07 | 0.07 | .34 |

| Dx = BN × A:I | .001 | .08 | .99 | .24 | .09 | .008 | .02 | ,09 | .85 | −.15 | 0.08 | .07 |

| Dx = BED × A:I | .04 | .07 | .63 | .28 | .08 | <.001 | .17 | .24 | .46 | −.19 | 0.08 | .02 |

| Dx = AN × A:I | 0 | - | - | 0 | - | - | 0 | - | - | 0 | - | - |

| Dx = BN × A:O | −.07 | .11 | .53 | −.12 | .11 | .29 | −.17 | .10 | .10 | −0.003 | 0.10 | .98 |

| Dx = BED × A:O | −.22 | .09 | .02 | −.21 | .09 | .02 | −.16 | .30 | .60 | −0.03 | 0.10 | .77 |

| Dx = AN × A:O | 0 | - | - | 0 | - | - | 0 | - | - | 0 | - | - |

Note: Dx = diagnosis; BN = bulimia nervosa; BED = binge eating disorder; AN = anorexia nervosa; A:I = actual:ideal discrepancy; A:O = actual:ought discrepancy;

p < .05

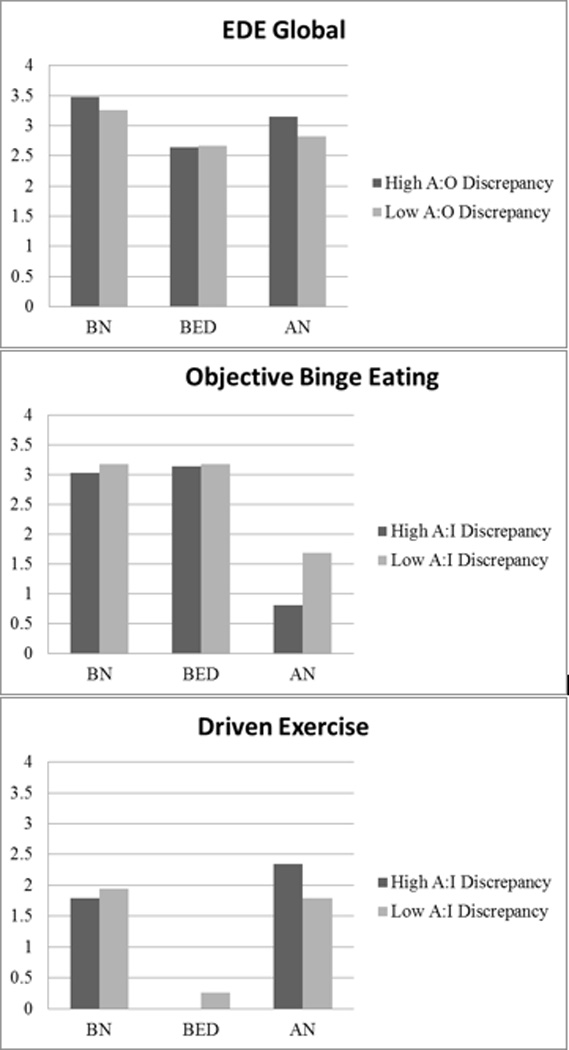

The analyses also revealed a significant interaction between ED diagnosis and A:O discrepancy for global ED psychopathology (Wald χ2= 6.63, p = .043) and significant interactions between ED diagnosis and A:I discrepancy for binge eating (Wald χ2= 12.84, p = .002) and driven exercise (Wald χ2= 6.15, p = .046). Figure 1 displays the predicted means for diagnosis for high and low values (±1 SD) of A:O self-discrepancy or A:I discrepancy. Of note, the same pattern of findings was found for the subscales of the EDE as was found for global ED psychopathology.

Figure 1.

Significant interactions between self-discrepancy and eating disorder diagnosis predicting eating disorder psychopathology

Discussion

Our findings are generally consistent with prior research that has supported the association between self-discrepancies and ED psychopathology (Strauman et al., 1991; Wonderlich et al., 2008), although the specific results differed in several ways from past research. Whereas Strauman et al. (1991) found that BN symptoms were associated with a form of A:I discrepancy and AN symptoms were associated with A:O discrepancy, we found that A:I discrepancy was more related to AN and A:O was more related to BN and BED. This difference possibly reflects the greater symptom severity and illness chronicity between the current participants and the college-student sample assessed by Strauman et al. (1991). These differences in findings may be due to sample factors (i.e., college students vs. individuals with diagnosed EDs, including those seeking treatment), measurement issues (i.e., interview vs. self-report, different measures of self-discrepancy), or statistical analyses. However, despite these differences, our findings extend knowledge of the association between self-discrepancies and ED diagnoses as well as specific ED symptoms.

A:I discrepancy was particularly salient among women with AN. Related to this finding, Strauman and Glenberg (1994) reported that A:I discrepancy was related to increased body size overestimation, which is prominent in AN. In addition, among women with AN, higher A:I discrepancy was associated with elevated driven exercise (see Figure 1). If driven exercise represents extreme attempts to control one’s weight and shape, the current results are consistent with the premise that this behavior may be driven in part by a strong desire to pursue one’s ideal self (i.e., particularly in the domain of weight and/or shape). Consistent with this assertion, Wonderlich et al (2008) found that women with BN described ideal standards that were more appearance-oriented than controls, whereas ought standards were not. Further, increased A:I discrepancy was associated with less binge eating among those with AN. Therefore, A:I discrepancy may be more prominent among those with AN who do not engage in binge eating, but engage in other ED behaviors.

Across diagnoses, greater A:O discrepancy was associated with both increased binge eating and purging. Given the salience of binge eating behaviors in BED and binge eating and purging behaviors in BN, these results may explain why A:O discrepancy is uniquely associated with BED and BN compared to AN. Finally, A:O discrepancy was related to severity of global ED psychopathology among those with AN and BN. Although A:O is associated with BED diagnosis, A:O discrepancy appears to be a marker of global ED severity in AN and BN, but not BED.

Taken together, the current results support the salience of self-discrepancy in EDs, suggesting it as a potential psychotherapeutic treatment target. Targeting A:I or A:O in relation to specific ED behaviors may be particularly useful. For example, for those reporting bulimic behaviors, A:O discrepancy may be especially important whereas A:I may be an important target among women with AN. Focusing on A:I and A:O discrepancy may be especially useful in ED treatment. Specifically, to target A:I discrepancy, therapists may focus on modifying individuals’ ideal standards to more reasonable standards that can be met (e.g., one’s ideal standard to be thinner may be unrealistic and impossible to reach). To target A:O discrepancy, it may be useful not only to potentially modify the standard itself, but also to address possible minimization of the positive, disregarded aspects of ones’ actual self (e.g., individuals who feel they must be thinner may disregard the positive aspects of their current body).

Strengths of this study include the use of interviews to assess ED diagnosis and symptoms, as well as self-discrepancies. While examining self-discrepancies across ED diagnostic groups represents an important addition to the literature, a limitation of our approach is that we used data from three separate studies with differing protocols. Thus, findings may not generalize to all individuals with AN, BN, and BED, and cross-diagnostic comparisons may be confounded by other differences in the studies. Furthermore, BN and BED samples were treatment-seeking samples whereas the AN sample was not. Although significantly different from 1, odds ratios for logistic regressions of self-discrepancies predicting ED diagnoses were relatively small. Thus, the effect sizes for study findings were modest. Finally, the racial and socioeconomic diversity of the samples was limited, and future research is needed to examine self-discrepancy among males with ED.

In sum, A:O and A:I discrepancy distinguished among ED diagnoses and symptoms. Overall, A:I discrepancy was related to AN diagnosis and A:O discrepancy was related to BN and BED diagnoses as well as bulimic behaviors. Future studies should examine mechanisms underlying the associations between self-discrepancies and various ED behaviors. For instance, Engel et al. (2005) found that affective variability mediated the association between self-discrepancy and restrictive behaviors and rituals among women with AN. Similar additional research on theoretically relevant underlying mechanisms is warranted which can potentially inform ED treatment and prevention efforts.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants R01DK61912, R01DK61973, and P30DK60456 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, grants R34MH077571, R01MH059674, and T32MH082761 from the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Neuropsychiatric Research Institute.

References

- Engel SG, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Crow S, Peterson CB, Gordon KH. The role of affect in the maintenance of anorexia nervosa: evidence from a naturalistic assessment of momentary behaviors and emotion. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:709–719. doi: 10.1037/a0034010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel SG, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Wright TL, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ, Venegoni EE. A study of patients with anorexia nervosa using ecologic momentary assessment. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2005;38:335–339. doi: 10.1002/eat.20184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, O’Connor M. Eating disorder examination. In: Fairburn CG, editor. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Heron KE, Smyth JM. Body image discrepancy and negative affect in women's everyday lives: An ecological momentary assessment evaluation of self-discrepancy theory. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2013;32:276–295. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET. Self-discrepancy theory: What patterns of self-beliefs cause people to suffer. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 1989;22:93–136. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET, Bond RN, Klein R, Strauman T. Self-discrepancies and emotional vulnerability: how magnitude, accessibility, and type of discrepancy influence affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:5–15. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET, Klein R, Strauman T. Self-concept discrepancy theory: A psychological model for distinguishing among different aspects of depression and anxiety. Social Cognition. 1985;3:51–76. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CB, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA. The efficacy of self-help group treatment and therapist-led group treatment for binge eating disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:1347–1354. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawdon AM, Cooper M, Seabrook R. The relationship between self-discrepancies, eating disorder and depressive symptoms in women. European Eating Disorders Review. 2007;15:207–212. doi: 10.1002/erv.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott L, O’Hara MW. Self-discrepancies in clinically anxious and depressed university students. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:282–287. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauman TJ, Glenberg AM. Self-concept and body-image disturbance: Which self-beliefs predict body size overestimation? Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1994;18:105–125. [Google Scholar]

- Strauman TJ, Vookles J, Berenstein V, Chaiken S, Higgins ET. Self-discrepancies and vulnerability to body dissatisfaction and disordered eating. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:946–956. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Engel SG, Peterson CB, Robinson MD, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Strauman TJ. Examining the conceptual model of integrative cognitive-affective therapy for BN: Two assessment studies. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41:748–754. doi: 10.1002/eat.20551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Peterson CB, Crosby RD, Smith TL, Klein MH, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ. A randomized controlled comparison of integrative cognitive-affective therapy (ICAT) and enhanced cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT-E) for bulimia nervosa. Psychological Medicine. 2014;44:543–553. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Peterson CB, Smith TL. Integrative cognitive-affective therapy for bulimia nervosa: A treatment manual. Guilford Publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]