Abstract

Introduction

The role of interpersonal factors has been proposed in various models of eating disorder (ED) psychopathology and treatment. We examined the independent and interactive contributions of two interpersonal-focused personality traits (i.e., social avoidance and insecure attachment) and reassurance seeking in relation to global ED psychopathology and depressive symptoms among women with bulimia nervosa (BN).

Method

Participants were 204 adult women with full or subclinical BN who completed a battery of self-report questionnaires. Hierarchical multiple OLS regressions including main effects and interaction terms were used to analyze the data.

Results

Main effects were found for social avoidance and insecure attachment in association with global ED psychopathology and depressive symptoms. In addition, two-way interactions between social avoidance and reassurance seeking were observed for both global ED psychopathology and depressive symptoms. In general, reassurance seeking strengthened the association between social avoidance and global ED psychopathology and depressive symptoms.

Conclusion

These results demonstrate the importance of reassurance seeking in psychopathology among women with BN who display personality features characterized by social avoidance.

Keywords: bulimia nervosa, interpersonal, insecure attachment, social avoidance, reassurance seeking

1. Introduction

Interpersonal factors have been emphasized in models of the development and maintenance of bulimia nervosa (BN)1 and form the foundation of interpersonal psychotherapy for eating disorders (EDs) (e.g., IPT).2 An extensive body of research has examined a variety of interpersonal factors in relation to ED psychopathology. For instance, research suggests that individuals with EDs display greater socio-emotional difficulties in comparison to healthy controls3 (and such difficulties are associated with increased severity and chronicity of ED symptoms). Furthermore, individuals with EDs are often biased toward rejection and avoidant of social reward.4 Individuals with EDs also tend to demonstrate more insecure attachments compared to healthy individuals (see Zachrisson & Skårderud, 2010 for a review)5. A number of factors may contribute to these interpersonal deficits and their association with ED psychopathology, particularly certain personality traits related to negative interpersonal styles.

Two related, yet distinct, interpersonally-focused personality traits include social avoidance and insecure attachment. Within this context, social avoidance is characterized by social detachment, poor social skills, and interpersonal difficulties, whereas insecure attachment is conceptualized as involving fear of abandonment and rejection by significant others, fear of separation, and seeking proximity to others. Research indicates that social avoidance and insecure attachment are associated with severity of ED psychopathology among individuals with EDs.6–7 Furthermore, individuals with bulimia nervosa (BN) score higher on both of these interpersonal personality dimensions compared to healthy controls,8–9 suggesting that they may be particularly salient for individuals with BN. Of note, insecure attachment and social avoidance are associated with elevated depressive symptoms,10–12 which are highly prevalent among individuals with BN. These interpersonal personality traits can be conceptualized as dispositional factors that increase individuals’ risk of psychopathology.13 More specifically, dispositional personality traits may interact with other individual difference variables to intensify risk for various psychological symptoms. For example, individuals with a socially avoidant personality may be at greater risk for depressive symptoms and ED psychopathology, but this link may be weaker or stronger based on the presence of other individual difference variables (e.g., fear of negative evaluations, rejection-sensitivity).

Reassurance seeking, an interpersonal behavior that involves excessive seeking of approval and reassurance from others, has received limited attention in the ED literature. Reassurance seeking is generally discussed as a maladaptive interpersonal behavior.14 Reassurance seeking may function as a form of rumination focused on insecurities involving others rather than being solely internally focused, which is the more typical ruminative style. Also, individuals may not always receive the reassurance that they desire from others or may discount others’ attempts to confirm positive feelings about them, which may result in distress. Further, others may experience annoyance due to excessive reassurance seeking15 or may become frustrated when their attempts to reassure are rejected,16 leading to problematic interpersonal relationships. In the limited existing literature on reassurance seeking in relation to ED psychopathology, findings suggest that this construct is associated with bulimic symptoms and prospectively predicts increases in ED symptoms in nonclinical samples.17–18 In addition, the extant literature has shown that reassurance seeking is closely related to depression.9 Consistent with interpersonal models of depression and EDs,2,19 reassurance seeking may be associated with increased ED psychopathology and depressive symptoms by creating interpersonal conflict and hindering the development of healthy social relationships.

Much of the existing research on reassurance seeking and interpersonal personality dimensions has focused on attachment anxiety. In fact, some research suggests that reassurance seeking is the manifestation of an anxious attachment that results in a propensity for excessively seeking reassurance from others to combat their fears of rejection and abandonment.20 A number of studies have supported an association between reassurance seeking and increased attachment anxiety.20–21 Less is known about reassurance seeking among those who are socially avoidant. However, previous studies have found that social anxiety22 and shyness23 are associated with reassurance seeking. Because socially avoidant individuals often lack perceived competence in social situations and may be inclined to believe that others possess unfavorable opinions about them, they may seek reassurance from others regarding their feelings toward them.

1.1. Current Study

Numerous etiological/maintenance models of both ED psychopathology and depression highlight the role of interpersonal factors, with avoidance of social experiences and fear of rejection/abandonment often addressed as particularly salient1,2 The importance of reassurance seeking in relation to ED psychopathology and depression has been similarly emphasized14,41 although the extent to which such behaviors may influence the association between personality factors and ED psychopathology or depression symptoms is unclear. Guided by the existing theoretical and empirical literature, the current study thus examined interpersonal personality traits (i.e., social avoidance and insecure attachment) and reassurance seeking behaviors in relation to ED psychopathology and depressive symptoms among women with BN. Importantly, this study extends previous research in this area by addressing both 1) theoretically relevant interpersonal personality traits in relation to two forms of psychopathology, and 2) reassurance seeking as an interpersonal factor that may modify the association between dispositional personality factors and each form of psychopathology.

Consistent with models conceptualizing personality traits as dispositional factors associated with risk of psychopathology symptoms, the first goal of this investigation was to examine the extent to which social avoidance and insecure attachment were uniquely related to ED psychopathology and depressive symptoms. It was hypothesized that social avoidance and insecure attachment would be uniquely positively associated with both ED psychopathology and depressive symptoms. Further, consistent with conceptualizations suggesting that other individual difference variables may modify associations between dispositional factors and psychopathology symptoms, the second goal of this investigation was to examine interactions between the interpersonal personality traits (i.e., social avoidance and insecure attachment) and reassurance seeking in relation to ED psychopathology and depressive symptoms. Given that reassurance seeking behaviors may lead to maladaptive interpersonal relationships, it was hypothesized that these interactions would be significant for both ED psychopathology and depressive symptoms. Specifically, it was anticipated that reassurance seeking would strengthen the associations between interpersonal personality traits (i.e., social avoidance and insecure attachment) and both forms of psychopathology.

2. Method

2.1 Participants and Procedure

Participants were 204 adult women with full (n = 161; 78.9%) or subclinical (n = 43; 21.1%) BN. The mean age of onset was 18.2 years (SD = 5.1) for women with full syndrome BN and 19.2 years (SD = 6.9) for women with subclinical BN. Regarding treatment history, 68.6% previously received psychotherapy for an ED. Approximately 32% of the sample reported currently taking antidepressants. The sample was primarily Caucasian (90.6%) with a mean age of 25.7 years (SD = 8.9). Mean body mass index (BMI) using self-reported height and weight was 23.0 kg/m2 (SD = 5.3). The sample consisted primarily of full time students (60%), with an income distribution as follows: 27.9% reported less than $10,000, 11.8% reported $10,000 to $20,000, 10.8% reported $20,000 to $30,000, 11.3% reported $30,000 to $40,000, and 38.2% reported greater than $40,000. Participants were recruited through ED clinics and community advertising from five sites in the Midwestern United States. Diagnoses were established via a telephone interview, during which Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV)24 criteria for BN were assessed. Subclinical BN was defined as (a) objective binge eating and compensatory behavior occurring at least once per week over the past three months, or (b) compensatory behavior occurring at least once per week along with subjective binge eating. Participants initially provided informed consent and then completed a battery of self-report questionnaires. The research was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at each participating institution.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Dimensional Assessment of Personality Psychopathology – Basic Questionnaire (DAPP-BQ)

The DAPP-BQ25 is a self-report measure of personality pathology traits. The current study used two subscales of the DAPP-BQ which measured specific interpersonally-relevant personality traits: social avoidance (e.g., “I never know how to act when there are other people around;” 16 items; α = .93) and insecure attachment (e.g., “I hate being separated from someone I love even for a few days;” 16 items; α = .91). Participants rated each statement on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The subscales of the DAPP-BQ have demonstrated adequate psychometric properties among psychiatric samples25, and have been used in a variety of studies of EDs.26–28

2.2.2 Depressive Interpersonal Relationships Inventory-Reassurance Seeking Subscale. (DIRI-RS)

The 4-item DIRI-RS14 is a self-report measure of reassurance seeking. Participants responded to items on a scale ranging from 1 (no, not at all) to 7 (yes, very much). A sample item is “Do you often find yourself asking the people you feel close to how they truly feel about you?” Joiner and Metalsky14 established the factor structure and validity of the DIRI-RS. Cronbach’s alpha for the measure was .92 in the current sample.

2.2.3. Eating Disorder Examination – Questionnaire (EDE-Q)

The 36-item EDE-Q29 is a self-report measure of ED psychopathology that includes subscales assessing shape concern, weight concern, eating concern, and restraint. Participants rated items on a scale ranging from 0 to 6 with response options varying across items. The EDE-Q has shown excellent reliability and validity.30 Good concordance rates have been shown between the EDE-Q and the Eating Disorder Examination interview.32 In this study, only the EDE-Q Global score, the mean of the four subscales, was used (α = .89).

2.2.4 Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Self-Report (IDS-SR)

The IDS-SR33 is a 30-item scale that measures depressive symptoms (e.g., sadness, changes in appetite, loss of interest). Participants rated items on a scale ranging from 0 to 3 with severity-based response options for each item, e.g., 0 (I do not feel sad), 1 (I feel sad less than half the time), 2 (I feel sad more than half the time), and 3 (I feel sad nearly all of the time). The IDS-SR is strongly associated with other established measures of depressive symptoms.34 Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was .90 in the current sample.

2.3 Data Analysis Strategy

Zero-order correlations were calculated to examine bivariate relationships between variables. Two hierarchical multiple ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions were calculated with global ED psychopathology and depressive symptoms as the dependent variables. In step 1 of each model, main effects for social avoidance, insecure attachment, and reassurance seeking, as well as a covariate (standardized BMI), were entered. In step 2 of each model, two-way interactions between the interpersonal personality traits (i.e., social avoidance and insecure attachment) and reassurance seeking were entered. Variables included in interaction terms were centered to reduce multicollinearity and facilitate interpretation.

3. Results

Zero-order correlations between depressive symptoms and social avoidance, insecure attachment, and reassurance seeking were .56 (p < .001), .36 (p < .001), and .36 (p < .001), respectively. Zero-order correlations between global ED psychopathology and social avoidance, insecure attachment, and reassurance seeking were .36 (p < .001), .30 (p < .001), and .29 (p < .001), respectively.

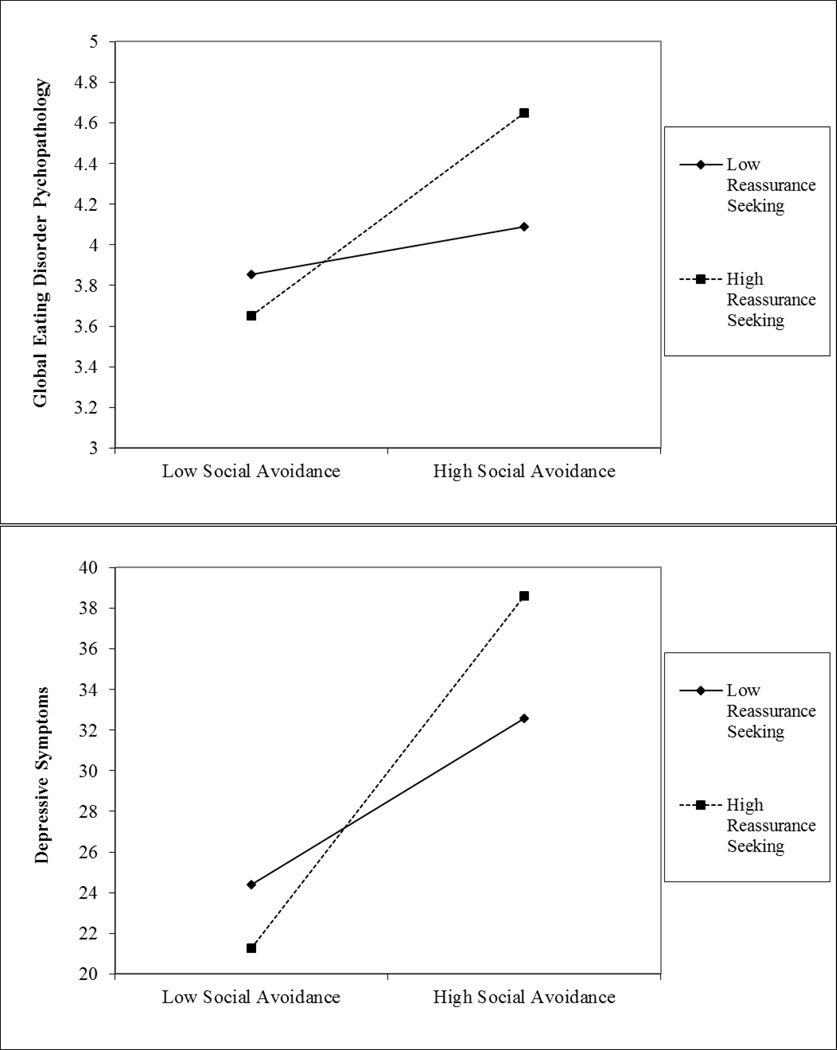

Results of the hierarchical multiple OLS regressions are displayed in Table 1. For global ED psychopathology, there were significant main effects for social avoidance (β = .30, p < .001) and insecure attachment (β = .16, p = .04), with higher scores associated with greater global ED psychopathology. Similarly, for depressive symptoms, there were significant main effects for social avoidance (β = .51, p < .001) and insecure attachment (β = .16, p = .02), with higher scores associated with greater depressive symptoms. There was no main effect for reassurance seeking for global ED psychopathology (β = .09, p = .27) or depressive symptoms (β = .06, p = .40). Additionally, there was a significant two-way interaction between social avoidance and reassurance seeking for both global ED psychopathology (β = .14, p = .04) and depressive symptoms (β = .18, p = .004; see Figure 1). Specifically, higher levels of reassurance seeking strengthened the association between social avoidance and global ED psychopathology, as well as social avoidance and depressive symptoms. There was not a significant interaction between insecure attachment and reassurance seeking for global ED psychopathology (β = .03, p = .68) or depressive symptoms (β = −.09, p = .15). The full models explained 21% of the variance in global ED psychopathology and 39% of the variance in depressive symptoms.

Table 1.

Interactions among Interpersonal Personality Dimensions and Reassurance Seeking Associated with Eating Disorder Psychopathology and Depressive Symptoms

| ED Psychopathology | Depressive Symptoms | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | R2 | ΔR2 | F | B | β | R2 | ΔR2 | F | |

| Step 1 | .19 | 11.14*** | .37 | 27.71*** | ||||||

| Body mass index (z) | .08 | .08 | 1.13 | .09 | ||||||

| Social avoidance | .02*** | .27 | .42*** | .47 | ||||||

| Insecure attachment | .01* | .16 | .14* | .16 | ||||||

| RS | .02 | .10 | .17 | .09 | ||||||

| Step 2 | .21 | .02 | 8.46*** | .39 | .02 | 20.68*** | ||||

| Body mass index (z) | .07 | .07 | 1.07 | .09 | ||||||

| Social avoidance | .02*** | .30 | .46*** | .51 | ||||||

| Insecure attachment | .01* | .16 | .14* | .16 | ||||||

| RS | .01 | .09 | .11 | .06 | ||||||

| Social avoidance X RS | .002* | .14 | .02** | .18 | ||||||

| Insecure attachment X RS | .000 | .03 | −.01 | −.09 | ||||||

Note:

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05;

RS = reassurance seeking

Figure 1.

Two-way interactions of social avoidance and reassurance seeking predicting global ED psychopathology and depressive symptoms. High and low levels of the variables are plotted at +1 and −1 standard deviation from the mean.

4. Discussion

This study examined the independent and interactive contributions of social avoidance, insecure attachment, and reassurance seeking in relation to global ED psychopathology and depressive symptoms among women with BN. Results were generally consistent with the first hypothesis. Specifically, both insecure attachment and social avoidance were uniquely positively associated with global ED psychopathology and depressive symptoms. This finding is consistent with conceptualizations of these personality traits as dispositional factors that may increase risk for symptoms of these two forms of psychopathology. Also, results correspond to studies that have found greater social avoidance and insecure attachment in BN.8–9 Further, reassurance seeking was associated with both depressive symptoms and global ED psychopathology at the zero-order level, but was not uniquely associated with either dependent variable when accounting for the other variables and covariate. The second hypothesis was partially confirmed. Specifically, there were significant interactions between reassurance seeking and social avoidance for both depressive symptoms and global ED psychopathology, but interactions between reassurance seeking and insecure attachment were nonsignificant for both forms of psychopathology. Thus, these findings suggest that reassurance seeking is an interpersonal behavior that modifies the association between the dispositional factor of social avoidance and two forms of psychopathology (i.e., depressive symptoms and global ED psychopathology).

With regard to social avoidance, the current results suggest that women with BN who are higher in social avoidance generally report more depressive symptoms and greater global ED psychopathology. There are several possible explanations for this finding. For instance, socially avoidant women may have poorer self-regulation, may not elicit protective benefits of social support, and may be socially isolated and anxious, increasing the risk of psychopathology.35–38 Alternatively, it is possible that greater depressive symptoms and global ED psychopathology promote increased social avoidance. Insecure attachment was also uniquely related to increased global ED psychopathology and depressive symptoms. Given evidence linking insecure attachment with body dissatisfaction,6–7,39 one potential explanation for this finding is that those with an insecure attachment may engage in eating disorder symptoms like purging in an attempt to achieve or maintain an appearance that they believe is appealing to others with the goal of lessening the chance of abandonment. This pursuit may cause women to become overly concerned and dissatisfied with their shape and weight if they do not perceive the approval they desire. Insecure attachment may be related to depressive symptoms through a number of factors such as dysfunctional attitudes (e.g., inappropriate beliefs about the self and world) and low self-esteem as well as interpersonal stressors.40 Finally, the absence of a main effect for reassurance seeking suggests that this construct is not independently associated with global ED psychopathology and depressive symptoms when controlling for interpersonally-relevant personality traits, although it does interact meaningfully with social avoidance in relation to global ED psychopathology and depressive symptoms.

The results of this investigation indicate that reassurance seeking had minimal impact on global ED psychopathology at lower levels of social avoidance. However, at higher levels of social avoidance, greater reassurance seeking was associated with elevated global ED psychopathology. The pattern of findings was similar for depressive symptoms. Specifically, at levels of low social avoidance, greater reassurance seeking was related to lower levels of depressive symptoms. In contrast, at higher levels of social avoidance, reassurance seeking was associated with elevated depressive symptoms. These results suggest that possessing simultaneous tendencies for avoiding social interactions and excessively seeking reassurance may represent a risk factor for increased severity of BN and depressive symptoms. Reassurance seeking may represent a compulsive and ultimately maladaptive behavior used by socially avoidant individuals to regulate emotions and anxiety.22 Because individuals with BN who are more socially avoidant may have limited interpersonal connections, excessive reassurance seeking may negatively impact the few relationships they do have. Previous research has indicated that reassurance seeking may be an expression of an anxious attachment.21 Yet, there were no interactions between insecure attachment and reassurance seeking associated with either global ED psychopathology or depressive symptoms in this sample of women with BN. Further research will be needed to clarify the nature of the associations between insecure attachments and reassurance seeking, particularly in relation to various forms of psychopathology.

Although the current findings further our knowledge about interpersonal factors, both dispositional and behavioral, in relation to global ED psychopathology and depressive symptoms among women with BN, some limitations of this study must be noted. First, clinical diagnoses were made via telephone interviews, which could have introduced bias in diagnostic decisions due to not being able to confirm weight/height. Also, although the measures selected for this study are widely used with strong psychometric support, all constructs were assessed using self-report questionnaires. Furthermore, the nature of the sample limits the generalizability to other populations (i.e., adolescents, ethnic minorities, males with BN, and those with EDs other than BN). Additionally, the cross-sectional design limits our ability to make inferences about directionality of the effects. Future studies should use longitudinal methodologies to examine interpersonal factors as prospective predictors of ED psychopathology and depressive symptoms. Finally, many women in the study previously received treatment, which may have had an effect on the associations among variables.

Despite these limitations, however, these findings have significant clinical implications for the treatment of BN. Notably, these results support the potential utility of assessing and addressing high levels of reassurance seeking among those individuals with BN who are more socially avoidant. Fairburn41 specifically discussed the importance of addressing reassurance seeking in the context of shape checking in cognitive behavioral treatment for EDs. Also, insecure attachment may be a meaningful target in treatment, particularly given that stressful interpersonal events may act as precipitants of negative affect and subsequent ED behaviors.42 Taken together, these findings are of particular relevance to ED treatments that focus on or address interpersonal factors as they relate to ED psychopathology, such as IPT, integrative cognitive-affective therapy,43 and dialectical behavior therapy.44 Focusing on the role of interpersonal factors and the strengthening of adaptive interpersonal skills may have utility in alleviating both ED psychopathology and depressive symptoms. Finally, because treating long-standing dispositional factors (e.g., personality traits) can be challenging,45 treating individual difference variables that are potentially more amenable to change (e.g., reassurance seeking) may have clinical utility. Further research is needed to determine ways in which reassurance-seeking as a clinical target can be incorporated into current treatments for BN, as well as emerging and novel interventions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants: University of Missouri Research Council; John Simon Guggenheim Foundation; NIH 1 R01-MH/DK58820; NIH 1 R01-DK61973; NIH 1 R01-MH59100; NIH 1 R01-MH66287; NIH P30-DK50456; K02-MH65919; R01 MH 59234; NIH T32MH082761 and Walden W. and Jean Young Shaw Foundation.

References

- 1.Arcelus J, Haslam M, Farrow C, Meyer C. The role of interpersonal functioning in the maintenance of eating psychopathology: A systematic review and testable model. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:156–167. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilfley DE, MacKenzie KR, Welch RR, Ayres VE, Weissman MM. Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Group. New York: Basic Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison A, Tchanturia K, Naumann U, Treasure J. Social emotional functioning and cognitive styles in eating disorders. Brit J Clin Psychol. 2012;51:261–279. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.2011.02026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardi V, Matteo RD, Corfield F, Treasure J. Social reward and rejection sensitivity in eating disorders: An investigation of attentional bias and early experiences. World J Biol Psychia. 2013;14:622–633. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2012.665479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zachrisson HD, Skårderud F. Feelings of insecurity: Review of attachment and eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2010;18:97–106. doi: 10.1002/erv.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abbate-Daga G, Gramaglia C, Amianto F, Marzola E, Fassino S. Attachment insecurity, personality, and body dissatisfaction in eating disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198:520–524. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181e4c6f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Illing V, Tasca GA, Balfour L, Bissada H. Attachment insecurity predicts eating disorder symptoms and treatment outcomes in a clinical sample of women. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198:653–659. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181ef34b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruce KR, Steiger H, Koerner NM, Israel M, Young SN. Bulimia nervosa with co-morbid avoidant personality disorder: Behavioural characteristics and serotonergic function. Psychol Med. 2004;34:113–124. doi: 10.1017/s003329170300864x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leonard S, Steiger H, Kao A. Childhood and adulthood abuse in bulimic and nonbulimic women prevalences and psychological correlates. Int J Eat Disorder. 2003;33:397–405. doi: 10.1002/eat.10176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aluja A, Blanch À, Blanco E, Martí-Guiu M, Balada F. The Dimensional Assessment of Personality Psychopathology Basic Questionnaire: Shortened versions item analysis. Span J Psychol. 2014;17:E102. doi: 10.1017/sjp.2014.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giovanni AD, Carla G, Enrica M, Federico A, Maria Z, Secondo F. Eating disorders and major depression: Role of anger and personality. Depress Res Treat. 2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/194732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tasca GA, Szadkowski L, Illing V, Trinneer A, Grenon R, Demidenko N, et al. Adult attachment, depression, and eating disorder symptoms: The mediating role of affect regulation strategies. Pers Indiv Differ. 2009;47:662–667. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tackett JL. Evaluating models of the personality–psychopathology relationship in children and adolescents. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:584–599. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joiner TE, Metalsky GI. Excessive reassurance seeking: Delineating a risk factor involved in the development of depressive symptoms. Psychol Sci. 2001;12:371–378. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dill JC, Anderson CA. Loneliness, shyness, and depression: The etiology and interrelationships of everyday problems in living. In: Joiner T, Coyne JC, editors. The interactional nature of depression: Advances in interpersonal approaches. Washington, D.C: APA; 1999. pp. 93–125. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joiner TE, Alfano MS, Metalsky GI. Caught in the crossfire: Depression, self-consistency, self-enhancement, and the response of others. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1993;12:113–134. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooley E, Toray T, Valdez N, Tee M. Risk factors for maladaptive eating patterns in college women. Eat Weight Disord-St. 2007;12:132–139. doi: 10.1007/BF03327640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Selby EA, Anestis MD, Joiner TE. Understanding the relationship between emotional and behavioral dysregulation: Emotional cascades. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46:593–611. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coyne JC. Toward an interactional description of depression. Psychiatr. 1976;39:28–40. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1976.11023874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evraire LE, Ludmer JA, Dozois DJ. The influence of priming attachment styles on excessive reassurance seeking and negative feedback seeking in depression. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2014;33:295–318. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaver PR, Schachner DA, Mikulincer M. Attachment style, excessive reassurance seeking, relationship processes, and depression. Pers Soc Psychol B. 2005;31:343–359. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heerey EA, Kring AM. Interpersonal consequences of social anxiety. J Abnor Psychol. 2007;116:125–134. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joiner TE. Correlation between excessive reassurance-seeking and traits of shyness and sociability. 1998 Unpublished data. [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Livesley WJ, Jackson DN. Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology—Basic Questionnaire: Technical manual. Port Huron, MI: Sigma Assessment Systems; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldner EM, Srikameswaran S, Schroeder ML, Livesley WJ, Birmingham CL. Dimensional assessment of personality pathology in patients with eating disorders. Psychiat Res. 1999;85:151–159. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(98)00145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lavender JM, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Mitchell JE, Crow S, et al. Personality-based subtypes of anorexia nervosa: Examining validity and utility using baseline clinical variables and ecological momentary assessment. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51:512–517. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Joiner T, Peterson CB, Bardone-Cone A, Klein M, et al. Personality subtyping and bulimia nervosa: Psychopathological and genetic correlates. Psychol Med. 2005;35:649–657. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704004234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disorder. 1994;16:363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berg KC, Peterson CB, Frazier P, Crow SJ. Psychometric evaluation of the eating disorder examination and eating disorder examination-questionnaire: A systematic review of the literature. Int J Eat Disorder. 2012;45:428–438. doi: 10.1002/eat.20931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C, Beumont PJV. Validity of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) in screening for eating disorders in community samples. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42:551–567. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00161-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rush AJ, Giles DE, Schlesser MA, Fulton CL, Weissenburger J, Burns C. The inventory for depressive symptomatology (IDS): Preliminary findings. Psychiat Res. 1986;18:65–87. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(86)90060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Carmody TJ, Biggs MM, Shores-Wilson K, Ibrahim H, Crismon ML. One-year clinical outcomes of depressed public-sector outpatients: A benchmark for subsequent studies. Biol Psychiat. 2014;56:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baumeister RF, DeWall CN, Ciarocco NJ, Twenge JM. Social exclusion impairs self-regulation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;88:589–604. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bodell LP, Smith AR, Holm-Denoma JM, Gordon KH, Joiner TE. The impact of perceived social support and negative life events on bulimic symptoms. Eat Behav. 2011;12:44–48. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hinrichsen H, Waller G, van Gerko K. Social anxiety and agoraphobia in the eating disorders: Associations with eating attitudes and behaviours. Eat Behav. 2004;5:285–290. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waller G, Dickson C, Ohanian V. Cognitive content in bulimic disorders: Core beliefs and eating attitudes. Eat Behav. 2002;3:171–178. doi: 10.1016/s1471-0153(01)00056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Troisi A, Di Lorenzo G, Alcini S, Nanni RC, Di Pasquale C, Siracusano A. Body dissatisfaction in women with eating disorders: Relationship to early separation anxiety and insecure attachment. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:449–453. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000204923.09390.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hankin BL, Kassel JD, Abela JR. Adult attachment dimensions and specificity of emotional distress symptoms: Prospective investigations of cognitive risk and interpersonal stress generation as mediating mechanisms. Pers Soc Psychol B. 2005;31:136–151. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldschmidt AB, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Lavender JM, Peterson CB, et al. Ecological momentary assessment of stressful events and negative affect in bulimia nervosa. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82:30–39. doi: 10.1037/a0034974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wonderlich SA, Peterson CB, Smith TL, Klein MH, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ. Integrative cognitive-affective therapy for bulimia nervosa: A treatment manual. New York: Guilford Press; 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Safer D, Telch C, Chen E. Dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating and bulimia. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davison SE. Principles of managing patients with personality disorder. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2002;8:1–9. [Google Scholar]