Abstract

Type B γ-aminobutyric acid receptor (GABABR) is a G protein-coupled receptor that regulates neurotransmitter release and neuronal excitability throughout the brain. In various neurons, GABABRs are concentrated at excitatory synapses. Although these receptors are assumed to respond to GABA spillover from neighboring inhibitory synapses, their function is not fully understood. Here we show a previously undescribed function of GABABR exerted independent of GABA. In cerebellar Purkinje cells, interaction of GABABR with extracellular Ca2+ ( ) leads to a constitutive increase in the glutamate sensitivity of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 (mGluR1). mGluR1 sensitization is clearly mediated by GABABR because it is absent in GABABR1 subunit-knockout cells. However, the mGluR1 sensitization does not require Gi/o proteins that mediate the GABABR's classical functions. Moreover, coimmunoprecipitation reveals complex formation between GABABR and mGluR1 in the cerebellum. These findings demonstrate that GABABR can act as

) leads to a constitutive increase in the glutamate sensitivity of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 (mGluR1). mGluR1 sensitization is clearly mediated by GABABR because it is absent in GABABR1 subunit-knockout cells. However, the mGluR1 sensitization does not require Gi/o proteins that mediate the GABABR's classical functions. Moreover, coimmunoprecipitation reveals complex formation between GABABR and mGluR1 in the cerebellum. These findings demonstrate that GABABR can act as  -dependent cofactors to enhance neuronal metabotropic glutamate signaling.

-dependent cofactors to enhance neuronal metabotropic glutamate signaling.

Keywords: calcium, cerebellum, G protein-coupled receptor, oligomerization, Purkinje cell

The type B γ-aminobutyric acid receptor (GABABR) is a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) distributed throughout the brain (1–3). GABABR regulates neurotransmitter release and neuronal excitability via Gi/o proteins (4). In the classic view, GABABR responds to GABA released from inhibitory presynaptic terminals (4). However, in some central neurons including cerebellar Purkinje cells, postsynaptic GABABRs are concentrated perisynaptically at the excitatory synapses and present sparsely at the inhibitory synapses (5–7). Because GABABRs are insensitive to the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate, a physiological role of GABABR at excitatory synapses was assumed to depend on γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) spillover from neighboring inhibitory synapses (8, 9).

The extracellular domain of GABABR has an amino acid sequence homology to that of Ca2+-sensing receptor (CaR) (10). Some studies in the heterologous expression systems (11, 12) revealed that GABABR indeed interacts with extracellular Ca2+  . Point mutation experiments indicate that the proximity of the GABA-binding site of GABABR1 subunit (GBR1) is responsible for this interaction (11). Although

. Point mutation experiments indicate that the proximity of the GABA-binding site of GABABR1 subunit (GBR1) is responsible for this interaction (11). Although  -GABABR interaction does not activate G proteins (12), it causes a remarkable conformational change of GABABR as

-GABABR interaction does not activate G proteins (12), it causes a remarkable conformational change of GABABR as  allosterically shifts GABA–GABABR affinity (11, 12). The

allosterically shifts GABA–GABABR affinity (11, 12). The  dose-dependence of this modulation suggests that GABABR are normally almost saturated by physiological levels (1–2 mM) of

dose-dependence of this modulation suggests that GABABR are normally almost saturated by physiological levels (1–2 mM) of  . Although a computational model (13) predicts that the

. Although a computational model (13) predicts that the  level in the very tight space of synaptic cleft may fluctuate during synaptic transmission, such a fluctuation is unlikely to spread to the perisynaptic site (14). Thus, virtually all of the perisynaptic GABABR should always interact with

level in the very tight space of synaptic cleft may fluctuate during synaptic transmission, such a fluctuation is unlikely to spread to the perisynaptic site (14). Thus, virtually all of the perisynaptic GABABR should always interact with  . In this study, we explored whether GA2BABR exerts a neuronal function through interaction with

. In this study, we explored whether GA2BABR exerts a neuronal function through interaction with  as the first step toward the understanding of the physiological role of GABABR at excitatory synapses. Given that

as the first step toward the understanding of the physiological role of GABABR at excitatory synapses. Given that  -GABABR interaction does not trigger diffusible G protein signaling (12),

-GABABR interaction does not trigger diffusible G protein signaling (12),  activity at GABABR is likely to influence a local target(s). A possible target is metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 (mGluR1) (15, 16), which is expressed in many central neurons and mediates slow postsynaptic potentials (17, 18), intracellular Ca2+ mobilization (19–21), synaptic plasticity (22–25), and developmental synapse elimination (24, 26). In cerebellar Purkinje cells, mGluR1 colocalizes with GABABR at the annuli of the dendritic spines innervated by excitatory parallel fibers (7, 27). We have previously shown that mGluR1 signaling in Purkinje cells is enhanced as a consequence of interaction between

activity at GABABR is likely to influence a local target(s). A possible target is metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 (mGluR1) (15, 16), which is expressed in many central neurons and mediates slow postsynaptic potentials (17, 18), intracellular Ca2+ mobilization (19–21), synaptic plasticity (22–25), and developmental synapse elimination (24, 26). In cerebellar Purkinje cells, mGluR1 colocalizes with GABABR at the annuli of the dendritic spines innervated by excitatory parallel fibers (7, 27). We have previously shown that mGluR1 signaling in Purkinje cells is enhanced as a consequence of interaction between  and an unknown surface molecule(s) (28). For the reasons mentioned above, we considered GABABR as a likely candidate for such a surface molecule.

and an unknown surface molecule(s) (28). For the reasons mentioned above, we considered GABABR as a likely candidate for such a surface molecule.

In Purkinje cells, mGluR1 outnumbers the other mGluR subtypes (16) and operates an inward cation current (17, 18, 29–31) carried by transient receptor potential C1 subunit-containing channels (32) exclusively via Gq protein (33). We could precisely evaluate the glutamate responsiveness of mGluR1 by measuring this inward current. These measurements revealed that  –GABABR interaction led to a constitutive increase in the glutamate sensitivity of mGluR1. This effect was clearly mediated by GABABR because it was absent in GABABR1 subunit-knockout (GBR1-KO) animal-derived cells. However, the

–GABABR interaction led to a constitutive increase in the glutamate sensitivity of mGluR1. This effect was clearly mediated by GABABR because it was absent in GABABR1 subunit-knockout (GBR1-KO) animal-derived cells. However, the  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization is distinguished from the classic functions of GABABR (4) for its independence of Gi/o proteins. Moreover, we used coimmunoprecipitation to reveal complex formation between cerebellar GABABR and mGluR1. These findings demonstrate that GABABR can function as a

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization is distinguished from the classic functions of GABABR (4) for its independence of Gi/o proteins. Moreover, we used coimmunoprecipitation to reveal complex formation between cerebellar GABABR and mGluR1. These findings demonstrate that GABABR can function as a  -dependent cofactor that constitutively enhances neuronal metabotropic glutamate signaling.

-dependent cofactor that constitutively enhances neuronal metabotropic glutamate signaling.

Methods

Cell Culture. Dissociated cerebellar neurons from the perinatal C57BL/6 mouse embryos were cultured in a low-serum medium for 9–22 days as described (34). In some experiments, pertussis toxin (PTX) or its A-protomer (PTX-AP) was added to the medium ≥13–16 h before recordings. Purkinje cells were identified by their large somata (≥20 μm) and/or thick primary dendrites.

In Fig. 3, GBR1 mutant mice (35) mated to C57BL/6 mice were used. WT [GBR1(+/+)] and GBR1-KO [GBR1(-/-)] mice were generated by mating the heterozygotes. The neonates were genotyped by PCR (37 cycles of 97°C for 20 s, 60°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 30 s) with the following primers: Neo5, 5′-TCCTGCCGAGAAAGTATC-3′; Neo3, 5′-GTCAAGAAGGCGATAGAAGGC-3′; GABAbEx10F, 5′-ATGCAGGAGGGTCTCCCCCAGCCG-3′; and GABAbEx10R, 5′-ACTTACCGAACGTGGGAGTTGTAG-3′. Neo5/Neo3 primers and GABAbEx11–5/GABAbEx11–3 primers amplified a 460-bp fragment from the mutant allele and a 157-bp fragment from the WT allele, respectively. Cerebellar cells from each neonate were separately cultured in a different dish.

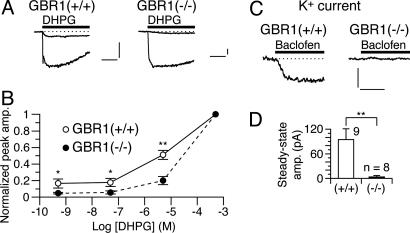

Fig. 3.

Genetic depletion of GBR1 abolishes the  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization. (A and B) Dose–response relations of DHPG-evoked inward currents in Purkinje cells derived from the WT [GBR1(+/+)] and GBR1-KO [GBR1(-/-)] littermates. CaCl2 (2 mM) in the saline. Vhold, -70 mV. (A) Each set of superimposed traces indicates the sample responses of a cell to 0.05 and 500 μM DHPG (thick bar). (Calibration bars, 10 s and 50 pA.) (B) Plots summarize the dose–response relations from five to eight cells per point. * and **, P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 between the WT and GBR1-KO cells (rank sum test), respectively. (C and D) Functional expression of GABABR in the WT and GBR1-KO Purkinje cells tested by monitoring the GABABR-operated inwardly rectifying K+ currents (see Fig. 4E). Vhold, -90 mV. EK, -57.6 mV. (C) Each trace indicates a sample response to 3 μM baclofen (thick bars). (Calibration bars, 10 s and 100 pA.) (D) Plots summarize the quasi-steady-state amplitudes of the baclofen-induced currents. **, P = 0.0056, t test.

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization. (A and B) Dose–response relations of DHPG-evoked inward currents in Purkinje cells derived from the WT [GBR1(+/+)] and GBR1-KO [GBR1(-/-)] littermates. CaCl2 (2 mM) in the saline. Vhold, -70 mV. (A) Each set of superimposed traces indicates the sample responses of a cell to 0.05 and 500 μM DHPG (thick bar). (Calibration bars, 10 s and 50 pA.) (B) Plots summarize the dose–response relations from five to eight cells per point. * and **, P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 between the WT and GBR1-KO cells (rank sum test), respectively. (C and D) Functional expression of GABABR in the WT and GBR1-KO Purkinje cells tested by monitoring the GABABR-operated inwardly rectifying K+ currents (see Fig. 4E). Vhold, -90 mV. EK, -57.6 mV. (C) Each trace indicates a sample response to 3 μM baclofen (thick bars). (Calibration bars, 10 s and 100 pA.) (D) Plots summarize the quasi-steady-state amplitudes of the baclofen-induced currents. **, P = 0.0056, t test.

Electrophysiology. Somatic whole-cell recordings were made from cultured Purkinje cells in a perforated- or ruptured-patch mode. The pipette solution for the perforated-patch recordings consisted of 95 mM Cs2SO4, 15 mM CsCl, 0.4 mM CsOH, 8 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Hepes, and 200 μg/ml amphotericin B (pH 7.35). The pipette solution for the ruptured-patch recordings consisted of 130 mM k-d-gluconate, 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM Hepes, 0.5 mM ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethylether-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid, 4 mM Mg-ATP, 0.4 mM Na2-GTP; the total Mg level was adjusted to 5.2 mM with MgCl2, and the total K level and pH were adjusted to 150.6 mM and 7.3, respectively, with KCl, KOH, and/or d-gluconic acid. The bath was perfused at a rate of 1–2 ml/min with a saline consisting of 116 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 1.1 mM NaH2PO4, 23.8 mM NaHCO3, 2 mM CaCl2, 0.3 mM MgCl2, 5.5 mM d-glucose, and 5 mM Hepes (pH 7.3, 25°C). We blocked voltage-gated Na+ channels and ionotropic glutamate and GABA receptors by supplementing the saline with 0.3 μM tetrodotoxin, 10 μM 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione, or 10 μM 6-nitro-7-sulfamoylbenzo[f]quinoxaline-2,3-dione, 50 μM D(-)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid, and 10 μM (-)-bicuculline methochloride. CaCl2 in the saline was replaced with MgCl2 in some experiments. Signals were filtered at 0.05–1 kHz and sampled at 0.1–3 kHz by using an amplifier (Axopatch-1D, Axon, Foster City, California or EPC8 or 9/2, HEKA, Lambreht, Germany) driven by pulse software (versions 8.10–8.53, HEKA). Control and test solutions were delivered locally through wide-tipped pipettes under the control of gravity unless otherwise stated. We measured R,S-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG)-evoked inward currents in the perforated-patch mode after the initial rapid development of perforation [typically 10–30 min; series resistance (Rseries), 20–70 MΩ]. The peak amplitude of the inward currents rarely exceeded 150 pA. Larger inward currents were reassessed after the Rseries decreased below 50 MΩ. We measured the GABABR-operated inwardly rectifying K+ currents in the ruptured-patch mode, employing electronic Rseries compensation (by 50–60% of ≈15 MΩ) and the saline supplemented with 10.6 mM KCl.

Data Analysis. The peak amplitude of an inward current was measured on the record offline-filtered at 1 Hz as a difference from the prestimulus level to the maximal deflection during DHPG application. For each cell, the dose–response data of the inward currents were normalized to the value at a DHPG dose ([DHPG]) of 500 μM (the saturating dose regardless of the  level, refs. 28 and 36). A Hill function [r = rmax × d/(d + Kd) + c, where r is amplitude, rmax is maximal amplitude, d is dose, Kd is apparent dissociation constant, and c is basal level] was fitted to the dose–response data by nonlinear regression (×10 weighing at the minimum and maximum) by using sigmaplot software (version 4.0, SPSS, Chicago).

level, refs. 28 and 36). A Hill function [r = rmax × d/(d + Kd) + c, where r is amplitude, rmax is maximal amplitude, d is dose, Kd is apparent dissociation constant, and c is basal level] was fitted to the dose–response data by nonlinear regression (×10 weighing at the minimum and maximum) by using sigmaplot software (version 4.0, SPSS, Chicago).

The steady-state amplitude of a baclofen-induced current was measured as a difference from the prestimulus level to the mean level over 9–10 s after baclofen onset.

Groups of numerical data are presented as mean ± SEM. Groups of raw values and normalized scores were compared by t test (with ANOVA for more than two groups) and rank sum test, respectively.

Coimmunoprecipitation. Adult C57BL6 mouse cerebella were homogenized in 10 volumes of a buffer [10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5/0.32 M sucrose/1 mM PMSF, an EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics)] and centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min. The crude membrane was obtained by centrifugation of the supernatant at 17,000 × g for 40 min, solubilized in a lysis buffer (1% Nonidet P-40/0.5% sodium deoxycholate/0.1% SDS/25 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5/137 mM NaCl/3 mM KCl/1 mM PMSF/inhibitor cocktail) at 4°C for 60 min, and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 60 min. The supernatant was checked for its protein level with Coomassie Plus (Pierce), diluted 2-fold with a detergent-free lysis buffer, and incubated with guinea pig normal serum (7 μl, Cappel) or a guinea pig antiserum against GBR1a/b (7 μl, Pharmingen 60696E) (2) at 4°C for 12 h. The samples were rotated with Protein-A Sepharose beads (Amersham Pharmacia) at 4°C for 2 h, and the beads were collected with a microspin column (Amersham Pharmacia) and washed five times with the lysis buffer with half-reduced detergents. The bound fractions were eluted with 2× SDS sample buffer and boiled for 5 min. The proteins fractionated by SDS/8% PAGE were transferred to a poly(vinylidene difluoride) membrane (Immobilon-P, Millipore). Immunoblots for a mouse monoclonal anti-mGluR1α Ab (1:200, Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY) with a peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG Ab (1:2,000, Jackson ImmunoResearch) or a peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig IgG Ab (1:2,000, Jackson ImmunoResearch) were visualized by using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Pharmacia).

Results

–GABABR Interaction Increases the Glutamate Sensitivity of mGluR1. We previously reported that

–GABABR Interaction Increases the Glutamate Sensitivity of mGluR1. We previously reported that  enhances neuronal mGluR1-operated responses to low doses of glutamate analogs (28, 36). This enhancement occurs commonly for mGluR1-operated responses mediated by different signaling/effector molecules (28). Thus,

enhances neuronal mGluR1-operated responses to low doses of glutamate analogs (28, 36). This enhancement occurs commonly for mGluR1-operated responses mediated by different signaling/effector molecules (28). Thus,  is thought to increase glutamate sensitivity of mGluR1 (referred the to as

is thought to increase glutamate sensitivity of mGluR1 (referred the to as  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization, see Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) rather than the coupling efficacy of the signaling cascades.

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization, see Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) rather than the coupling efficacy of the signaling cascades.  appears to act via a surface molecule(s) because an intracellularly applied Ca2+ chelator fails to abolish the mGluR1 sensitization (28). Here we tested whether the

appears to act via a surface molecule(s) because an intracellularly applied Ca2+ chelator fails to abolish the mGluR1 sensitization (28). Here we tested whether the  –GABABR the interaction contributes to mGluR1 sensitization.

–GABABR the interaction contributes to mGluR1 sensitization.

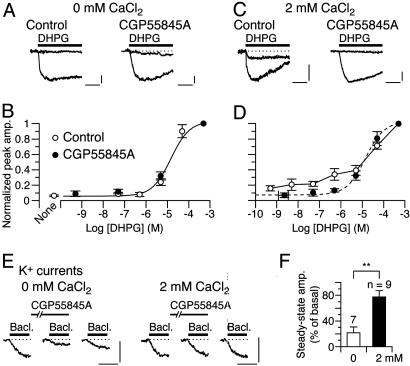

We evaluated mGluR1's glutamate sensitivity in cultured Purkinje cells by monitoring inward currents evoked by DHPG, a group I mGluR-selective glutamate analog (Fig. 1 A–D). As previously reported (28, 36), inclusion of CaCl2 (2 mM) in the saline increased the relative peak amplitudes of the inward currents at lower [DHPG] (Fig. 1 A and C, control traces). The threshold [DHPG] evoking an inward current was shifted from 0.5–5 μM to ≤0.5 nM (Fig. 1 B and D, open symbols).  has been suggested to interact with recombinant GABABR in proximity of the GABA-binding site (11). If similar interaction occurs for native GABABR, CGP55845A, a GABA-derivative GABABR antagonist (4) may interfere with

has been suggested to interact with recombinant GABABR in proximity of the GABA-binding site (11). If similar interaction occurs for native GABABR, CGP55845A, a GABA-derivative GABABR antagonist (4) may interfere with  –GABABR interaction. Addition of CGP55845A (2 μM) to the CaCl2-containing saline indeed completely abolished the

–GABABR interaction. Addition of CGP55845A (2 μM) to the CaCl2-containing saline indeed completely abolished the  -dependent enhancement seen at lower [DHPG] (Fig. 1 C and D). The threshold [DHPG] rose to 0.5–5 μM (Fig. 1D, filled symbols). CGP55845A (2 μM) by itself little affected the [DHPG]-response relation in the CaCl2-free saline (Fig. 1 A and B, “CGP55845A” traces and filled symbols). Thus, CGP55845A abolished the effect of

-dependent enhancement seen at lower [DHPG] (Fig. 1 C and D). The threshold [DHPG] rose to 0.5–5 μM (Fig. 1D, filled symbols). CGP55845A (2 μM) by itself little affected the [DHPG]-response relation in the CaCl2-free saline (Fig. 1 A and B, “CGP55845A” traces and filled symbols). Thus, CGP55845A abolished the effect of  through interfering with

through interfering with  –GABABR interaction but not through directly modulating GABABR, mGluR1, or the cation channels.

–GABABR interaction but not through directly modulating GABABR, mGluR1, or the cation channels.

Fig. 1.

–GABABR interaction leads to the mGluR1 sensitization. (A–D) Dose–response relations of DHPG-evoked inward currents in the CaCl2-free (A and B) or 2 mM CaCl2-containing (C and D) saline. Holding potential (Vhold), -70 mV. Each set of superimposed traces (A and C) indicates the sample responses of a different Purkinje cell to 0.05 and 500 μM DHPG (thick bar) in the absence (“Control”) or presence of 2 μM CGP55845A, a GABABR antagonist. (Calibration bars, 10 s and 20 pA.) (B and D) Plots summarize the dose–response relations from 4–16 cells per point. (B) “None,” the saline applied without DHPG. Sigmoid curves, Hill functions with apparent Kd of 14.7 μM(B) and 14.3 μM(D). (E and F) Possible competition between

–GABABR interaction leads to the mGluR1 sensitization. (A–D) Dose–response relations of DHPG-evoked inward currents in the CaCl2-free (A and B) or 2 mM CaCl2-containing (C and D) saline. Holding potential (Vhold), -70 mV. Each set of superimposed traces (A and C) indicates the sample responses of a different Purkinje cell to 0.05 and 500 μM DHPG (thick bar) in the absence (“Control”) or presence of 2 μM CGP55845A, a GABABR antagonist. (Calibration bars, 10 s and 20 pA.) (B and D) Plots summarize the dose–response relations from 4–16 cells per point. (B) “None,” the saline applied without DHPG. Sigmoid curves, Hill functions with apparent Kd of 14.7 μM(B) and 14.3 μM(D). (E and F) Possible competition between  and CGP55845A for GABABR tested by the blockade of GABABR-operated inwardly rectifying K+ currents (see Fig. 4E). (E) Each trace set indicates the sample responses of a different Purkinje cell to 1 μM baclofen, a GABABR agonist (thick bars) measured before (basal), on, and ≥90 s after a 100-s CGP55845A treatment (6 nM, thin bars) in the CaCl2-free or 2 mM CaCl2-containing saline. Vhold, -90 mV. EK, -57.6 mV. (Calibration bars, 10 s and 50 pA.) (F) Plots summarize the quasi-steady-state amplitudes of the baclofen-induced currents after the CGP55845A treatment. **, P = 0.0059, rank sum test.

and CGP55845A for GABABR tested by the blockade of GABABR-operated inwardly rectifying K+ currents (see Fig. 4E). (E) Each trace set indicates the sample responses of a different Purkinje cell to 1 μM baclofen, a GABABR agonist (thick bars) measured before (basal), on, and ≥90 s after a 100-s CGP55845A treatment (6 nM, thin bars) in the CaCl2-free or 2 mM CaCl2-containing saline. Vhold, -90 mV. EK, -57.6 mV. (Calibration bars, 10 s and 50 pA.) (F) Plots summarize the quasi-steady-state amplitudes of the baclofen-induced currents after the CGP55845A treatment. **, P = 0.0059, rank sum test.

We confirmed this point by monitoring a GABABR-operated inwardly rectifying K+ current (see Fig. 4E), which was slowly induced by baclofen (1 μM), a GABABR-selective agonist (Fig. 1E). In the CaCl2-free saline, CGP55845A (6 nM) reversibly blocked the baclofen-induced currents by 78.5 ± 9.1% (n = 7; Fig. 1 E and F), indicating that CGP55845A occupies a majority of the GABABR population under this condition. Inclusion of CaCl2 (2 mM) in the saline reduced the extent of blockade to 22.4 ± 9.6% (n = 9, Fig. 1 E and F), indicating that CGP55845A and  impede each other from interacting with GABABR. The results in Fig. 1 clearly demonstrate that

impede each other from interacting with GABABR. The results in Fig. 1 clearly demonstrate that  –GABABR interaction leads to mGluR1 sensitization.

–GABABR interaction leads to mGluR1 sensitization.

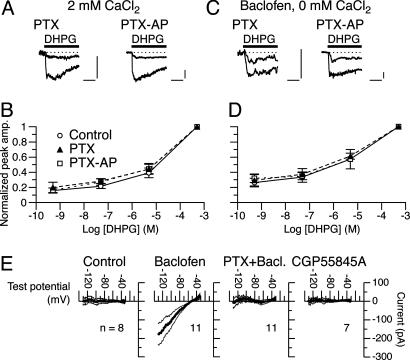

Fig. 4.

GABABR mediates the mGluR1 sensitization independent of Gi/o proteins. (A–D) Dose–response relations of DHPG-evoked inward currents in Purkinje cells pretreated with PTX or PTX-AP (500 ng/ml, ≥13 h). The saline contained either 2 mM CaCl2 (A and B) or 30 nM baclofen (C and D). Vhold, -70 mV. Each set of superimposed traces (A and C) indicates the sample responses of a different cell to 0.05 and 500 μM DHPG (thick bar). Calibration bars, 10 s and 20 pA. Plots in B and D summarize the dose–response relations from 4–16 cells per point. Control data were obtained from cells cultured in a medium containing the vehicle (BSA) but not the toxins. (E) Ramp I–V relations of currents induced by the normal (Control), 3 μM baclofen-containing saline, or 2 μM CGP55845A-containing saline in Purkinje cells. Each current was extracted as a difference between total currents measured before and after a 2-min treatment with the test agents. Thick and thin lines, mean ± SEM. Test potential was ramped at a rate of -100 mV/s. CaCl2 (2 mM) in the saline. EK, -57.6 mV. PTX + Bacl., baclofen-induced currents in cells pretreated with PTX (500 ng/ml, ≥16 h).

One study (37) suggests close association of neuronal CaR and mGluR1. However, CaR might not be important for the  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization. Amyloid β1–40 (1 μM), a CaR agonist (38), did not enhance the DHPG-evoked inward currents (n = 10, data not shown). Immunohistochemistry failed to detect CaR in mouse cerebellar Purkinje cells (M. Watanabe, personal communication).

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization. Amyloid β1–40 (1 μM), a CaR agonist (38), did not enhance the DHPG-evoked inward currents (n = 10, data not shown). Immunohistochemistry failed to detect CaR in mouse cerebellar Purkinje cells (M. Watanabe, personal communication).

GABABR may also mediate a  -dependent kinetic change of the inward currents (see Supporting Text for a detailed explanation). During a 30-s DHPG application (500 μM), the inward current was inactivated by 64.9 ± 9.2% (n = 7) from the peak level in the 2 mM CaCl2-containing saline, whereas it was inactivated by 45.4 ± 8.8% (n = 10) in the CaCl2-free saline (Fig. 1 A and C, control traces). CGP55845A (2 μM) significantly reduced this

-dependent kinetic change of the inward currents (see Supporting Text for a detailed explanation). During a 30-s DHPG application (500 μM), the inward current was inactivated by 64.9 ± 9.2% (n = 7) from the peak level in the 2 mM CaCl2-containing saline, whereas it was inactivated by 45.4 ± 8.8% (n = 10) in the CaCl2-free saline (Fig. 1 A and C, control traces). CGP55845A (2 μM) significantly reduced this  -dependent acceleration of inactivation (29.7 ± 5.3%, n = 10; P < 0.01, t test; Fig. 1C, CGP55845A traces), indicating the involvement of GABABR in the kinetic change.

-dependent acceleration of inactivation (29.7 ± 5.3%, n = 10; P < 0.01, t test; Fig. 1C, CGP55845A traces), indicating the involvement of GABABR in the kinetic change.

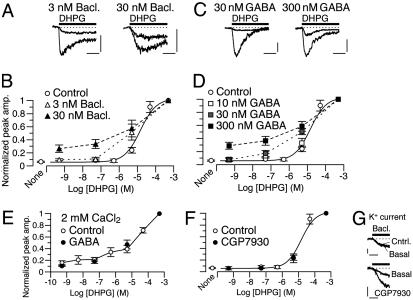

Similarity Between the Effects of  and GABABR Agonists. In the CaCl2-free saline, baclofen enhanced the relative peak amplitudes of inward currents at lower [DHPG] in a concentration-dependent fashion (3–30 nM; Fig. 2 A and B). Baclofen (30 nM) lowered the threshold [DHPG] from 0.5–5 μM to ≤0.5 nM (Fig. 2B). GABA displayed similar enhancement in a concentration-dependent fashion (10–300 nM; Fig. 2 C and D). GABA (300 nM) lowered the threshold [DHPG] from 0.5–5 μM to ≤0.5 nM (Fig. 2D). These effects of GABA were not artifacts produced by an ionotropic GABA receptor current because GABA at 30–300 nM did not activate any detectable current (n = 5, data not shown). Also, the agonist concentrations used here are in the range of the reported binding affinities for GABABR (39). The similarity between the effects of

and GABABR Agonists. In the CaCl2-free saline, baclofen enhanced the relative peak amplitudes of inward currents at lower [DHPG] in a concentration-dependent fashion (3–30 nM; Fig. 2 A and B). Baclofen (30 nM) lowered the threshold [DHPG] from 0.5–5 μM to ≤0.5 nM (Fig. 2B). GABA displayed similar enhancement in a concentration-dependent fashion (10–300 nM; Fig. 2 C and D). GABA (300 nM) lowered the threshold [DHPG] from 0.5–5 μM to ≤0.5 nM (Fig. 2D). These effects of GABA were not artifacts produced by an ionotropic GABA receptor current because GABA at 30–300 nM did not activate any detectable current (n = 5, data not shown). Also, the agonist concentrations used here are in the range of the reported binding affinities for GABABR (39). The similarity between the effects of  and the GABABR agonists (Fig. 2 A–D) further supports the involvement of GABABR in the mGluR1 sensitization.

and the GABABR agonists (Fig. 2 A–D) further supports the involvement of GABABR in the mGluR1 sensitization.

Fig. 2.

GABABR agonists mimic the  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization. (A–D) Dose–response relations of DHPG-evoked inward currents in the absence (“Control”) or presence of the labeled GABABR agonist. No CaCl2 in the saline. Vhold, -70 mV. (A and C) Each set of superimposed traces indicates the sample responses of a different Purkinje cell to 0.05 and 500 μM DHPG (thick bar). Calibration bars, 10 s and 20 pA (A) or 50 pA (C). (B and D) Plots summarize the dose–response relations from four to nine cells per point. Sigmoid curves indicate Hill functions with a Kd of 14.7 μM. (E) Mean dose–response relation of DHPG-evoked inward currents in the absence (“Control”) or presence of 10 nM GABA. CaCl2 (2 mM) in the saline. Vhold, -70 mV. n = 5–16 Purkinje cells per point. (F) Mean dose–response relation of DHPG-evoked inward currents in the absence (“Control”) or presence of 10 μM CGP7930, a GABABR potentiator. No CaCl2 in the saline. Vhold, -70 mV. n = 4–9 Purkinje cells per point. Sigmoid curve indicates a Hill function with a Kd of 14.7 μM. (G) Confirmation of GABABR potentiation by CGP7930 on the GABABR-operated inwardly rectifying K+ current (see Fig. 4E). No CaCl2 in the saline. Vhold, -90 mV. EK, -57.6 mV. Each set of superimposed traces indicates the sample responses of a different Purkinje cell to 1 μM GABA (thick bars) measured before (“Basal”) and after a 60-s treatment with the control saline or 10 μM CGP7930. (Calibration bars, 10 s and 50 pA.)

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization. (A–D) Dose–response relations of DHPG-evoked inward currents in the absence (“Control”) or presence of the labeled GABABR agonist. No CaCl2 in the saline. Vhold, -70 mV. (A and C) Each set of superimposed traces indicates the sample responses of a different Purkinje cell to 0.05 and 500 μM DHPG (thick bar). Calibration bars, 10 s and 20 pA (A) or 50 pA (C). (B and D) Plots summarize the dose–response relations from four to nine cells per point. Sigmoid curves indicate Hill functions with a Kd of 14.7 μM. (E) Mean dose–response relation of DHPG-evoked inward currents in the absence (“Control”) or presence of 10 nM GABA. CaCl2 (2 mM) in the saline. Vhold, -70 mV. n = 5–16 Purkinje cells per point. (F) Mean dose–response relation of DHPG-evoked inward currents in the absence (“Control”) or presence of 10 μM CGP7930, a GABABR potentiator. No CaCl2 in the saline. Vhold, -70 mV. n = 4–9 Purkinje cells per point. Sigmoid curve indicates a Hill function with a Kd of 14.7 μM. (G) Confirmation of GABABR potentiation by CGP7930 on the GABABR-operated inwardly rectifying K+ current (see Fig. 4E). No CaCl2 in the saline. Vhold, -90 mV. EK, -57.6 mV. Each set of superimposed traces indicates the sample responses of a different Purkinje cell to 1 μM GABA (thick bars) measured before (“Basal”) and after a 60-s treatment with the control saline or 10 μM CGP7930. (Calibration bars, 10 s and 50 pA.)

The  -Dependent GluR1 Sensitization Occurs Independent of Ambient GABA. Although the recording chamber was continuously perfused, GABA released from the cultured cells could accumulate in the chamber (ambient GABA).

-Dependent GluR1 Sensitization Occurs Independent of Ambient GABA. Although the recording chamber was continuously perfused, GABA released from the cultured cells could accumulate in the chamber (ambient GABA).  may potentiate GABA-GABABR interaction (11, 12). Thus,

may potentiate GABA-GABABR interaction (11, 12). Thus,  could possibly sensitize mGluR1 through such potentiation. We excluded this possibility in the following two experiments.

could possibly sensitize mGluR1 through such potentiation. We excluded this possibility in the following two experiments.

First, an increase of ambient GABA failed to facilitate the  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization (Fig. 2 D and E). The ambient GABA level in the chamber might usually be <10 nM because the threshold GABA concentration for the GABA-dependent mGluR1 sensitization was 10–30 nM (Fig. 2D). Thus, addition of 10 nM exogenous GABA to the saline should substantially increase the ambient GABA level. However, this manipulation did not further augment the relative amplitudes of the inward currents at lower [DHPG] in the 2 mM CaCl2-containing saline (Fig. 2E). This result indicates that the effect of

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization (Fig. 2 D and E). The ambient GABA level in the chamber might usually be <10 nM because the threshold GABA concentration for the GABA-dependent mGluR1 sensitization was 10–30 nM (Fig. 2D). Thus, addition of 10 nM exogenous GABA to the saline should substantially increase the ambient GABA level. However, this manipulation did not further augment the relative amplitudes of the inward currents at lower [DHPG] in the 2 mM CaCl2-containing saline (Fig. 2E). This result indicates that the effect of  is independent of the ambient levels of GABA.

is independent of the ambient levels of GABA.

Second, CGP7930, a drug which potentiates GABA-GABABR interaction (40) failed to mimic the  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization. Inclusion of CGP7930 (10 μM) in the CaCl2-free saline did not augment the relative amplitudes of the inward currents at lower [DHPG] (Fig. 2F). This result indicates that the ambient GABA level was too low to induce mGluR1 sensitization even with the aid of the potentiator. We confirmed the effectiveness of CGP7930 by monitoring the GABABR-operated inwardly rectifying K+ currents (Fig. 2G, see Fig. 4E). CGP7930 (10 μM, 60 s) augmented 1 μM GABA-induced currents by 339.7 ± 106.1% (n = 5), and this extent of augmentation was significantly greater than that with the control saline (by 11.2 ± 8.8%, n = 5; P = 0.012, rank sum test; Fig. 2G). These results suggest that the

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization. Inclusion of CGP7930 (10 μM) in the CaCl2-free saline did not augment the relative amplitudes of the inward currents at lower [DHPG] (Fig. 2F). This result indicates that the ambient GABA level was too low to induce mGluR1 sensitization even with the aid of the potentiator. We confirmed the effectiveness of CGP7930 by monitoring the GABABR-operated inwardly rectifying K+ currents (Fig. 2G, see Fig. 4E). CGP7930 (10 μM, 60 s) augmented 1 μM GABA-induced currents by 339.7 ± 106.1% (n = 5), and this extent of augmentation was significantly greater than that with the control saline (by 11.2 ± 8.8%, n = 5; P = 0.012, rank sum test; Fig. 2G). These results suggest that the  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization from

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization from  –GABABR interaction rather than a

–GABABR interaction rather than a  -dependent potentiation of GABA–GABABR interaction.

-dependent potentiation of GABA–GABABR interaction.

Absence of the  -Dependent mGluR1 Sensitization in GBR1-KO Cells. The involvement of GABABR in the

-Dependent mGluR1 Sensitization in GBR1-KO Cells. The involvement of GABABR in the  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization was further examined by using the GBR1-KO mice (35). Genetic depletion of GBR1 also causes heavy down-regulation of GBR2 (35). Therefore, the GBR1-KO mice lack functional GABABR consisting of GBR1 and GBR2 (1–3). We compared the [DHPG] dependence of the inward currents between Purkinje cells derived from the GBR1-KO mice and WT littermates (Fig. 3 A and B). Despite the presence of 2 mM CaCl2 in the saline, obvious inward currents were evoked only by ≥5 μM DHPG in the GBR1-KO cells (Fig. 3 A and B). By contrast, detectable inward currents were evoked by ≥0.5 nM DHPG in the WT cells (Fig. 3 A and B). The relative peak amplitudes of the inward currents at 0.5 nM-5 μM in the GBR1-KO cells were significantly smaller than those in the WT cells (Fig. 3B). Absolute peak amplitude with 500 μM DHPG was not significantly different (P = 0.37, t test) between the GBR1-KO (250.5 ± 100.9 pA, n = 6) and WT (154.8 ± 46.4 pA, n = 8) cells. We confirmed that GBR1-KO cells indeed lacked functional GABABR by monitoring the GABABR-operated inwardly rectifying K+ currents (Fig. 3 C and D, see Fig. 4E). Baclofen (3 μM) induces the K+ currents in the WT cells but not the GBR1-KO cells (Fig. 3 C and D). These results strongly support the finding that GABABR mediates the

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization was further examined by using the GBR1-KO mice (35). Genetic depletion of GBR1 also causes heavy down-regulation of GBR2 (35). Therefore, the GBR1-KO mice lack functional GABABR consisting of GBR1 and GBR2 (1–3). We compared the [DHPG] dependence of the inward currents between Purkinje cells derived from the GBR1-KO mice and WT littermates (Fig. 3 A and B). Despite the presence of 2 mM CaCl2 in the saline, obvious inward currents were evoked only by ≥5 μM DHPG in the GBR1-KO cells (Fig. 3 A and B). By contrast, detectable inward currents were evoked by ≥0.5 nM DHPG in the WT cells (Fig. 3 A and B). The relative peak amplitudes of the inward currents at 0.5 nM-5 μM in the GBR1-KO cells were significantly smaller than those in the WT cells (Fig. 3B). Absolute peak amplitude with 500 μM DHPG was not significantly different (P = 0.37, t test) between the GBR1-KO (250.5 ± 100.9 pA, n = 6) and WT (154.8 ± 46.4 pA, n = 8) cells. We confirmed that GBR1-KO cells indeed lacked functional GABABR by monitoring the GABABR-operated inwardly rectifying K+ currents (Fig. 3 C and D, see Fig. 4E). Baclofen (3 μM) induces the K+ currents in the WT cells but not the GBR1-KO cells (Fig. 3 C and D). These results strongly support the finding that GABABR mediates the  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization.

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization.

The  -Dependent mGluR1 Sensitization Does Not Require Gi/o Proteins. In most neurons, GABABR is coupled to its effectors via Gi/o proteins (4). A previous study (8) reported that GABABR stimulation with GABA analogs results in Gi/o protein-dependent augmentation of mGluR1 responses. To examine the Gi/o protein-dependence of the mGluR1 sensitization studied here, we pretreated Purkinje cells with PTX (500 ng/ml, ≥13 h; Fig. 4 A–D). Although this pretreatment was expected to uncouple Gi/o proteins from GPCRs, it abolished neither the

-Dependent mGluR1 Sensitization Does Not Require Gi/o Proteins. In most neurons, GABABR is coupled to its effectors via Gi/o proteins (4). A previous study (8) reported that GABABR stimulation with GABA analogs results in Gi/o protein-dependent augmentation of mGluR1 responses. To examine the Gi/o protein-dependence of the mGluR1 sensitization studied here, we pretreated Purkinje cells with PTX (500 ng/ml, ≥13 h; Fig. 4 A–D). Although this pretreatment was expected to uncouple Gi/o proteins from GPCRs, it abolished neither the  -dependent (Fig. 4 A and B) nor baclofen-dependent (Fig. 4 C and D) enhancement of the relative peak amplitudes of the inward currents at lower [DHPG]. PTX did not have a nonspecific effect on the inward currents because its membrane-impermeant catalytic subunit (PTX-AP; 500 ng/ml, ≥13 h) had little effect on the [DHPG] dependences (Fig. 4 A–D). By contrast, the PTX pretreatment abolished the Gi/o protein-dependent augmentation of mGluR1 response. In Purkinje cells cultured for 11–16 days, the absolute peak amplitude of the DHPG (500 μM)-induced inward currents with 30 nM baclofen (41.0 ± 11.0 pA, n = 17) was significantly larger than that without baclofen (15.5 ± 6.0 pA, n = 10; P < 0.05, ANOVA and t test; data not shown). PTX (15.9 ± 2.8 pA, n = 11) but not PTX-AP (46.0 ± 9.4 pA, n = 9) significantly eliminated this effect of baclofen (data not illustrated).

-dependent (Fig. 4 A and B) nor baclofen-dependent (Fig. 4 C and D) enhancement of the relative peak amplitudes of the inward currents at lower [DHPG]. PTX did not have a nonspecific effect on the inward currents because its membrane-impermeant catalytic subunit (PTX-AP; 500 ng/ml, ≥13 h) had little effect on the [DHPG] dependences (Fig. 4 A–D). By contrast, the PTX pretreatment abolished the Gi/o protein-dependent augmentation of mGluR1 response. In Purkinje cells cultured for 11–16 days, the absolute peak amplitude of the DHPG (500 μM)-induced inward currents with 30 nM baclofen (41.0 ± 11.0 pA, n = 17) was significantly larger than that without baclofen (15.5 ± 6.0 pA, n = 10; P < 0.05, ANOVA and t test; data not shown). PTX (15.9 ± 2.8 pA, n = 11) but not PTX-AP (46.0 ± 9.4 pA, n = 9) significantly eliminated this effect of baclofen (data not illustrated).

We confirmed the effectiveness of the PTX pretreatment by monitoring the GABABR-operated inwardly rectifying K+ current (Fig. 4E). We extracted this current as a difference between the voltage ramp-activated currents recorded before and after application of baclofen (3 μM, 2 min). The baclofen-induced current displayed inward rectification and a reversal potential (-53.3 ± 3.1 mV, n = 11) close to the equilibrium potential of K+ (EK, -57.6 mV; Fig. 4E). This current might be carried by Gi/o protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K+ channels naturally occurring in Purkinje cells (41). The baclofen-induced current was not an artifact because it was not induced by the normal saline (Fig. 4E, control). The PTX pretreatment (500 ng/ml, ≥16 h) suppressed the baclofen-induced current (Fig. 4E, PTX + Bacl.), indicating that this pretreatment completely blocked Gi/o proteins in Purkinje cells. In addition, currents measured in the absence of exogenous GABABR agonists were not susceptible to CGP55845A (2 μM; Fig. 4E, CGP55845A). This result indicates that the GABABR-operated K+ current is not activated without exogenous GABABR agonists and that ambient GABA (see above) or  (12) in the normal saline does not facilitate GABABR–Gi/o protein signaling. The results in Fig. 4 clearly show that the mGluR1 sensitization studied here is independent of Gi/o proteins and distinct from the Gi/o protein-dependent augmentation of mGluR1 response (8).

(12) in the normal saline does not facilitate GABABR–Gi/o protein signaling. The results in Fig. 4 clearly show that the mGluR1 sensitization studied here is independent of Gi/o proteins and distinct from the Gi/o protein-dependent augmentation of mGluR1 response (8).

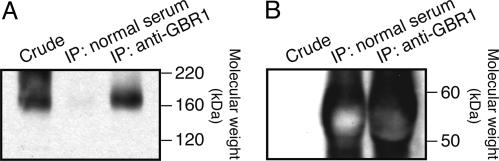

Complex Formation Between GABABR and mGluR1. In central neurons, mGluR1 and other GPCRs may oligomerize and functionally modulate one another (37, 42). GABABR and mGluR1 colocalize to the perisynaptic membrane of Purkinje cells (see Introduction). We used coimmunoprecipitation to test the possibility of complex formation between GABABR and mGluR1 in mouse cerebellum (Fig. 5). First, GABABR-associated proteins were collected by immunoprecipitation (IP) using a guinea pig anti-GBR1a/b antiserum. For control, mockup IP was done by using guinea pig normal serum. Then, these samples were analyzed by immunoblots using an anti-mGluR1α Ab, which was confirmed to react with mGluR1 monomer (≈160 kDa, ref. 27) in crude cerebellar membrane (Fig. 5A Left). This analysis detected mGluR1 in the IP product but not the control sample (Fig. 5A Right and Center, respectively). The absence of mGluR1 in the control sample is not attributable to the low amount of the blotting material because the control sample as well as the IP product contained high concentrations of the corresponding guinea pig sera (Fig. 5B). Results supporting GABABR–mGluR1 complex formation were obtained from four sessions of coimmuniprecipitation.

Fig. 5.

Complex formation of GABABR and mGluR1 in the cerebellum. (A) GABABR-associated mGluR1 in the cerebellar membrane was collected by IP using a guinea pig anti-GBR1a/b antiserum and then visualized in an immunoblot by using an anti-mGluR1α Ab (Right), which is confirmed to react with mGluR1 in crude cerebellar membrane (≈160 kDa, Left). (Center) Mockup IP using guinea pig normal serum yields no mGluR1. (B) An immunoblot using an anti-guinea pig IgG Ab indicates that both the test and mockup IP products contain high concentrations of the corresponding guinea pig sera. Thus, the absence of mGluR1 in the mockup IP product is not attributable to the low amount of the blotting material.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated how GABABR exerts neuronal function in the absence of GABA in cerebellar Purkinje cells. We found that the GABABR antagonist abolished the  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization (Fig. 1). This effect appeared to be caused by interference with

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization (Fig. 1). This effect appeared to be caused by interference with  –GABABR interaction (Fig. 1 E and F), which is consistent with a report (11) that this interaction occurs at the proximity of the GABA-binding site of GABABR. Thus,

–GABABR interaction (Fig. 1 E and F), which is consistent with a report (11) that this interaction occurs at the proximity of the GABA-binding site of GABABR. Thus,  -interacting GABABR may modulate mGluR1. The

-interacting GABABR may modulate mGluR1. The  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization was independent of the ambient levels of GABA (Fig. 2 D and E) and could not be mimicked by the drug potentiating GABA–GABABR interaction (Fig. 2 F and G). These results indicate that the key step for initiating the mGluR1 sensitization is

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization was independent of the ambient levels of GABA (Fig. 2 D and E) and could not be mimicked by the drug potentiating GABA–GABABR interaction (Fig. 2 F and G). These results indicate that the key step for initiating the mGluR1 sensitization is  –GABABR interaction itself, but not potentiation of ambient GABA–GABABR interaction that could result from an allosteric modulation of GABABR by

–GABABR interaction itself, but not potentiation of ambient GABA–GABABR interaction that could result from an allosteric modulation of GABABR by  (11, 12). The

(11, 12). The  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization was mimicked by the GABABR agonists (Fig. 2 A–D). The

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization was mimicked by the GABABR agonists (Fig. 2 A–D). The  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization was totally absent in the GBR1-KO cells (Fig. 3 A and B), which lacked functional GABABR (Fig. 3 C and D) (35). These results further support the involvement of functional GABABR in the mediation of the

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization was totally absent in the GBR1-KO cells (Fig. 3 A and B), which lacked functional GABABR (Fig. 3 C and D) (35). These results further support the involvement of functional GABABR in the mediation of the  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization. Taken together, these findings unequivocally demonstrate that

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization. Taken together, these findings unequivocally demonstrate that  -interacting GABABR can modulate neuronal metabotropic glutamate signaling without GABA.

-interacting GABABR can modulate neuronal metabotropic glutamate signaling without GABA.

We do not exclude a possibility that molecules other than GABABR mediate a minor part of the  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization. mGluR1 itself could serve as a mediator. In the heterologous systems, direct

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization. mGluR1 itself could serve as a mediator. In the heterologous systems, direct  –mGluR1 interaction leads to activation of mGluR1-operated cellular responses (43) as well as sensitization of the receptor (44). However, at least in the particular cell type used, GABABR is the predominant mediator as both CGP55845A treatment (Fig. 1 C and D) and genetic depletion of GBR1 (Fig. 3 A and B) completely abolished the

–mGluR1 interaction leads to activation of mGluR1-operated cellular responses (43) as well as sensitization of the receptor (44). However, at least in the particular cell type used, GABABR is the predominant mediator as both CGP55845A treatment (Fig. 1 C and D) and genetic depletion of GBR1 (Fig. 3 A and B) completely abolished the  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization.

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization.

In respect of the GABA and Gi/o protein independence, the  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization is distinguished from the classical functions of GABABR (4). The

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization is distinguished from the classical functions of GABABR (4). The  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization is also different from the previously reported Gi/o protein-dependent augmentation of mGluR1 responses by GABA analogs (8). The

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization is also different from the previously reported Gi/o protein-dependent augmentation of mGluR1 responses by GABA analogs (8). The  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization is thought to reflect changes in glutamate analog–mGluR1 interaction (Fig. 1 A–D). On the other hand, the Gi/o protein-dependent augmentation might reflect facilitation of coupling efficacy from mGluR1 to the effector (8) as it was observed for the inward currents evoked by the saturating dose of DHPG (28) (see Results).

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization is thought to reflect changes in glutamate analog–mGluR1 interaction (Fig. 1 A–D). On the other hand, the Gi/o protein-dependent augmentation might reflect facilitation of coupling efficacy from mGluR1 to the effector (8) as it was observed for the inward currents evoked by the saturating dose of DHPG (28) (see Results).

The exact molecular mechanism underlying functional linkage from  -interacting GABABR to mGluR1 remains to be elucidated. The mechanism should be independent of Gi/o proteins (Fig. 4). Interaction with

-interacting GABABR to mGluR1 remains to be elucidated. The mechanism should be independent of Gi/o proteins (Fig. 4). Interaction with  may change the conformation of GABABR (11, 12). There are increasing reports (42, 45, 46) that the ligand-dependent conformational change of a GPCR leads to modulation of closely associated adaptor proteins or GPCRs without the aid of G proteins. Such “direct” modulation is a possible mechanism because mGluR1 was obtained by coimmunoprecipitation for GBR1 (Fig. 5). Virtually all GBR1s are thought to participate in forming functional GABABR with GBR2 (47). In the cerebellum, mGluR1 is most concentrated in Purkinje cells (16). Thus, GABABR and mGluR1 are likely to form complexes in Purkinje cell with or without an intermediate molecule(s).

may change the conformation of GABABR (11, 12). There are increasing reports (42, 45, 46) that the ligand-dependent conformational change of a GPCR leads to modulation of closely associated adaptor proteins or GPCRs without the aid of G proteins. Such “direct” modulation is a possible mechanism because mGluR1 was obtained by coimmunoprecipitation for GBR1 (Fig. 5). Virtually all GBR1s are thought to participate in forming functional GABABR with GBR2 (47). In the cerebellum, mGluR1 is most concentrated in Purkinje cells (16). Thus, GABABR and mGluR1 are likely to form complexes in Purkinje cell with or without an intermediate molecule(s).

A majority of postsynaptic GABABR localize to the perisynaptic sites in central neurons including cerebellar Purkinje cells (7, 48). Although there is a model (13) suggesting that the  level in the synaptic cleft may fluctuate during synaptic transmission, such a fluctuation is unlikely to spread to the perisynaptic site (14). Thus, GABABR is thought to always interact with a relatively constant level of

level in the synaptic cleft may fluctuate during synaptic transmission, such a fluctuation is unlikely to spread to the perisynaptic site (14). Thus, GABABR is thought to always interact with a relatively constant level of  in the cerebrospinal fluid and therefore may possibly exert the mGluR1 sensitization in a constitutive fashion under physiological conditions in vivo. This constitutive fashion may confer the

in the cerebrospinal fluid and therefore may possibly exert the mGluR1 sensitization in a constitutive fashion under physiological conditions in vivo. This constitutive fashion may confer the  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization a different role from that of the Gi/o protein-dependent augmentation of mGluR1 response by GABABR (8). The Gi/o protein-dependent augmentation might transiently enhance mGluR1 signaling in response to GABA spillover from neighboring inhibitory synapses only when the inhibitory synapses are strongly activated (8, 9). By contrast, the constitutive

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization a different role from that of the Gi/o protein-dependent augmentation of mGluR1 response by GABABR (8). The Gi/o protein-dependent augmentation might transiently enhance mGluR1 signaling in response to GABA spillover from neighboring inhibitory synapses only when the inhibitory synapses are strongly activated (8, 9). By contrast, the constitutive  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization may contribute to the continuous maintenance of the normal efficacy of postsynaptic mGluR1-coupled signaling. In addition, GABA contained in the cerebrospinal fluid (a few tens of nanomolars in free form, ref. 49) might not show strong synergy with

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization may contribute to the continuous maintenance of the normal efficacy of postsynaptic mGluR1-coupled signaling. In addition, GABA contained in the cerebrospinal fluid (a few tens of nanomolars in free form, ref. 49) might not show strong synergy with  for mGluR1 sensitization (Fig. 2E). The

for mGluR1 sensitization (Fig. 2E). The  -dependent mGluR1 sensitization may also secure induction of long-term depression of the glutamate-responsiveness of Purkinje cells (Supporting Text and Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) and thus, may contribute to cerebellar motor learning (22, 24). Enhancement of mGluR1 signaling by

-dependent mGluR1 sensitization may also secure induction of long-term depression of the glutamate-responsiveness of Purkinje cells (Supporting Text and Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) and thus, may contribute to cerebellar motor learning (22, 24). Enhancement of mGluR1 signaling by  -interacting GABABR may occur in many other brain regions because of the overlapping cellular distributions of GABABR and mGluR1 (1–3, 7, 15, 16, 48, 50).

-interacting GABABR may occur in many other brain regions because of the overlapping cellular distributions of GABABR and mGluR1 (1–3, 7, 15, 16, 48, 50).

The findings of the present study demonstrate a previously undescribed function of GABABR as a  -dependent cofactor that constitutively enhances neuronal metabotropic glutamate signaling.

-dependent cofactor that constitutively enhances neuronal metabotropic glutamate signaling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. K. Yoshioka and Y. Kubo for helpful advice and S. Haruki for cell preparation. This work was supported by the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research and the Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, Culture and Technology of Japan, and by grants from the Novartis Foundation, the Cell Science Research Foundation, and the Uehara Memorial Foundation. B.B. is supported by Swiss Science Foundation Grant 3100-067100.01.

Author contributions: T.T. and M.K. designed research; T.T., K.A., K.H., and Y.H. performed research; H.v.d.P. and B.B. contributed new reagents or analytic tools; T.T., K.A., K.H., and Y.H. analyzed data; and T.T., B.B., and M.K. wrote the paper.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: IP, immunoprecipitation; GABABR, type B γ-aminobutyric receptor; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; CaR, Ca2+-sensing receptor; GBR1-KO, GABABR1 subunit-knockout; PTX, pertussis toxin; PTX-AP, PTX A protomer;  , extracellular Ca2+; mGluR1, metabotropic glutamate receptor 1; DHPG, R,S-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine; [DHPG], DHPG dose.

, extracellular Ca2+; mGluR1, metabotropic glutamate receptor 1; DHPG, R,S-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine; [DHPG], DHPG dose.

References

- 1.Jones, K. A., Borowsky, B., Tamm, J. A., Craig, D. A., Durkin, M. M., Dai, M., Yao, W. J., Johnson, M., Gunwaldsen, C., Huang, L. Y., et al. (1998) Nature 396, 674-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaupmann, K., Malitschek, B., Schuler, V., Heid, J., Froestl, W., Beck, P., Mosbacher, J., Bischoff, S., Kulik, A., Shigemoto, R., et al. (1998) Nature 396, 683-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuner, R., Kohr, G., Grunewald, S., Eisenhardt, G., Bach, A. & Kornau, H. C. (1999) Science 283, 74-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kerr, D. I. & Ong, J. (1995) Pharmacol. Ther. 67, 187-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fritschy, J.-M., Meskenaite, V., Weinmann, O., Honer, M., Benke, D. & Mohler, H. (1999) Eur. J. Neurosci. 11, 761-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ige, A. O., Bolam, J. P., Billinton, A., White, J. H., Marshall, F. H. & Emson, P. C. (2000) Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 83, 72-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kulik, A., Nakadate, K., Nyiri, G., Notomi, T., Malitschek, B., Bettler, B. & Shigemoto, R. (2002) Eur. J. Neurosci. 15, 291-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirono, M., Yoshioka, T. & Konishi, S. (2001) Nat. Neurosci. 4, 1207-1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dittman, J. S. & Regehr, W. G. (1997) J. Neurosci. 17, 9084-9059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown, E. M. & MacLeod, R. J. (2001) Physiol. Rev. 81, 239-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galvez, T., Urwyler, S., Prezeau, L., Mosbacher, J., Joly, C., Malitschek, B., Heid, J., Brabet, I., Froestl, W., Bettler, B., et al. (2000) Mol. Pharmacol. 57, 419-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wise, A., Green, A., Main, M. J., Wilson, R., Fraser, N. & Marshall, F. H. (1999) Neuropharmacology 38, 1647-1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vassilev, P. M., Mitchel, J., Vassilev, M., Kanazirska, M. & Brown, E. M. (1997) Biophys. J. 72, 2103-2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyashita, T. & Kubo, Y. (2000) Recept. Channels 7, 77-91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Houamed, K. M., Kuijper, J. L., Gilbert, T. L., Haldeman, B. A., O'Hara, P. J., Mulvihill, E. R., Almers, W. & Hagen, F. S. (1991) Science 252, 1318-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masu, M., Tanabe, Y., Tsuchida, K., Shigemoto, R. & Nakanishi, S. (1991) Nature 349, 760-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Batchelor, A. M. & Garthwaite, J. (1997) Nature 385, 74-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tempia, F., Miniaci, M. C., Anchisi, D. & Strata, P. (1998) J. Neurophysiol. 80, 520-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finch, E. A. & Augustine, G. J. (1998) Nature 396, 753-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Llano, I., Dreessen, J., Kano, M. & Konnerth, A. (1991) Neuron 7, 577-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takechi, H., Eilers, J. & Konnerth, A. (1998) Nature 396, 757-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aiba, A., Kano, M., Chen, C., Stanton, M. E., Fox, G. D., Herrup, K., Zwingman, T. A. & Tonegawa, S. (1994) Cell 79, 377-388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conquet, F., Bashir, Z. I., Davies, C. H., Daniel, H., Ferraguti, F., Bordi, F., Franz-Bacon, K., Reggiani, A., Matarese, V., Conde, F., et al. (2002) Nature 372, 237-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ichise, T., Kano, M., Hashimoto, K., Yanagihara, D., Nakao, K., Shigemoto, R., Katsuki, M. & Aiba, A. (2000) Science 288, 1832-1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shigemoto, R., Abe, T., Nomura, S., Nakanishi, S. & Hirano, T. (1994) Neuron 12, 1245-1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kano, M., Hashimoto, K., Kurihara, H., Watanabe, M., Inoue, Y., Aiba, A. & Tonegawa, S. (1997) Neuron 18, 71-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baude, A., Nusser, Z., Roberts, J. D., Mulvihill, E. R., McIlhinney, R. A. J. & Somogyi, P. (1993) Neuron 11, 771-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tabata, T., Aiba, A. & Kano, M. (2002) Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 20, 56-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canepari, M., Papageorgiou, G., Corrie, J. E., Watkins, C. & Ogden, D. (2001) J. Physiol. 533, 765-772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirono, M., Konishi, S. & Yoshioka, T. (1998) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 251, 753-758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tempia, F., Alojado, M. E., Strata, P. & Knopfel, T. (2001) J. Neurophysiol. 86, 1389-1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim, J. K., Kin, Y. S., Yuan, J. P., Petralia, R. S., Worley, P. F. & Linden, D. J. (2003) Nature 426, 285-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hartmann, J., Blum, R., Kovalchuk, Y., Adelsberger, H., Kuner, R., Durand, G. M., Miyata, M., Kano, M., Offermanns, S. & Konnerth, A. (2004) J. Neurosci., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Tabata, T., Sawada, S., Araki, K., Bono, Y., Furuya, S. & Kano, M. (2000) J. Neurosci. Methods 104, 45-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schuler, V., Luscher, C., Blanchet, C., Klix, N., Sansig, G., Klebs, K., Schmutz, M., Heid, J., Gentry, C., Urban, L., et al. (2001) Neuron 31, 47-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tabata, T. & Kano, M. (2004) Mol. Neurobiol. 29, 261-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gama, L., Wilt, S. G. & Breitwieser, G. E. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 39053-39059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ye, C., Ho-Pao, C. L., Kanazirska, M., Quinn, S., Rogers, K., Seidman, C. E., Seidman, J. G., Brown, E. M. & Vassilev, P. M. (1997) J. Neurosci. Res. 47, 547-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hill, D. R. & Bowery, N. G. (1981) Nature 290, 149-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Urwyler, S., Mosbacher, J., Lingenhoehl, K., Heid, J., Hofstetter, K., Froestl, W., Bettler, B. & Kaupmann, K. (2001) Mol. Pharmacol. 60, 963-971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karschin, C., Dissmann, E., Stuhmer, W. & Karschin, A. (1996) J. Neurosci. 16, 3559-3570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ciruela, F., Escriche, M., Burgueno, J., Angulo, E., Casado, V., Soloviev, M. M., Canela, E. I., Mallol, J., Chan, W.-Y., Lluis, C., et al. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 18345-18351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kubo, Y., Miyashita, T. & Murata, Y. (1998) Science 279, 1722-1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miyashita, T. & Kubo, Y. (2000) Recept. Channels 7, 25-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bouvier, M. (2001) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 274-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klinger, M., Freissmuth, M. & Nanoff, C. (2002) Cell. Signalling 14, 99-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benke, D., Honer, M., Michel, C., Bettler, B. & Mohler, H. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 27323-27330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lujan, R., Roberts, J. D., Shigemoto, R., Ohishi, H. & Somogyi, P. (1997) J. Chem. Neuroanat. 13, 219-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bohlen, P., Huot, S. & Palfreyman, M. G. (1979) Brain Res. 167, 297-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakanishi, S. (1994) Neuron 13, 1031-1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.