Abstract

Background and objectives

Depression is common in patients receiving chronic hemodialysis but seems to be ineffectively treated. We investigated the acceptance of antidepressant treatment by patients on chronic hemodialysis and their renal providers.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

As part of a clinical trial of symptom management in patients on chronic hemodialysis conducted from 2009 to 2011, we assessed depression monthly using the Patient Health Questionnaire 9. For depressed patients (Patient Health Questionnaire 9 score ≥10), trained nurses generated treatment recommendations and helped implement therapy if patients and providers accepted the recommendations. We assessed patients’ acceptance of recommendations, reasons for refusal, and provider willingness to implement antidepressant therapy. We analyzed data at the level of the monthly assessment.

Results

Of 101 patients followed for ≤12 months, 39 met criteria for depression (Patient Health Questionnaire 9 score ≥10 on one or more assessments). These 39 patients had depression on 147 of 373 (39%) monthly assessments. At 103 of these 147 (70%) assessments, patients were receiving antidepressant therapy, and at 51 of 70 (70%) assessments, patients did not accept nurses’ recommendations to intensify treatment. At 44 assessments, patients with depression were not receiving antidepressant therapy, and in 40 (91%) instances, they did not accept recommendations to start treatment. The primary reason that patients refused the recommendations was attribution of their depression to an acute event, chronic illness, or dialysis (57%). In 11 of 18 (61%) instances in which patients accepted the recommendation, renal providers were unwilling to provide treatment.

Conclusions

Patients on chronic hemodialysis with depression are frequently not interested in modifying or initiating antidepressant treatment, commonly attributing their depression to a recent acute event, chronic illness, or dialysis. Renal providers are often unwilling to modify or initiate antidepressant therapy. Future efforts to improve depression management will need to address these patient- and provider-level obstacles to providing such care.

Keywords: depression, acceptance, treatment, anti-depressant therapy, quality of life, symptoms, hemodialysis, psychological, Chronic Disease, Depressive Disorder, Disease Management, Fluid Therapy, Humans, Nurses, renal dialysis, Surveys and Questionnaires

Introduction

Patients receiving chronic outpatient hemodialysis (HD) experience a large burden of symptoms, of which depression is particularly common, affecting up to 25% of patients (1–6). Factors that likely contribute to the high point prevalence of depression include impaired functional status, adverse effects of a thrice weekly treatment, need for multiple medications that have untoward side effects, and loss of social support and vocational capacity (7–10). Among patients on chronic HD, the presence of depression is associated with missed and abbreviated dialysis treatments, emergency department visits and hospitalizations, impaired health–related quality of life, and increased mortality risk (2,7,11–14).

Given the prevalence and clinical significance of this comorbid condition in this patient group, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Quality Improvement Program (QIP) for ESRD recently mandated that all dialysis facilities report individual patient screening and treatment plans for depression (15). However, there is a dearth of data on the effectiveness of antidepressant therapy in patients on chronic HD. Although several small studies suggest that antidepressant medication and cognitive behavioral therapy may alleviate depressive symptoms in patients receiving chronic HD, the acceptance of such treatment by patients and renal providers remains unknown (16–19). We hypothesized that patients on chronic HD with depression may not want to receive treatment and that renal providers may be reluctant to prescribe treatment. To address this hypothesis, we sought to assess patient and renal provider acceptance of antidepressant treatment recommendations for depression that was identified at monthly assessments performed during a clinical trial of symptom management strategies in patients receiving chronic outpatient HD.

Materials and Methods

Patient Population

This study was based on an analysis of data collected as part of the Symptom Management Involving ESRD (SMILE) Trial, a prospective, multicenter, cluster–randomized trial that compared two strategies for the management of three common symptoms in adults receiving chronic thrice–weekly HD (Clinical Trials no. NCT00692419) (20,21). The SMILE Trial enrolled cognitively intact, English–speaking adults receiving outpatient HD at nine dialysis units in western Pennsylvania.

After enrollment into the SMILE Trial, the study team randomized participants into a feedback or management arm. In the feedback arm, a research coordinator assessed depression monthly using the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) and informed renal providers of their patients’ depression scores. Decisions about treatment were at the discretion of the provider. We did not assess patient preferences for antidepressant treatment in the feedback arm. In the management arm, nurses trained in the treatment of depression assessed patients for this condition on a monthly basis using the PHQ-9. When depression was identified, the nurses formulated pharmacologic and/or nonpharmacologic (i.e., referral for cognitive behavioral therapy or psychiatric evaluation) treatment recommendations on the basis of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense clinical practice treatment algorithms for the management of depression that were modified by the study investigators to account for medication dose adjustment in the setting of ESRD. The nurses discussed their recommendations with the patient and if accepted by the patient verbally at the time of or after this interaction, contacted the patient’s renal provider to discuss the recommendations (21). If the renal provider agreed with the proposed treatment, the nurse helped implement the therapy. Because this study sought to characterize patient and renal provider acceptance of recommendations for treatment of depression and such data collection was restricted to the management arm, we limited our study population to patients randomized to the management arm of the SMILE Trial who met criteria for depression on one or more monthly assessments. This optimized the number of patients included in this analysis. Patients were followed after randomization for up to 12 months. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for the SMILE Trial. All study procedures adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by an institutional review board.

Assessments of Depression and Patient and Renal Provider Acceptance of Treatment Recommendations

On a monthly basis, patients completed the PHQ-9, a validated tool to assess depressive symptoms in patients on chronic HD that has been shown to be highly predictive of the presence of depressive disorders (5). We considered a PHQ-9 score ≥10 to represent the presence of depressive symptoms, which we refer to as depression. For each monthly assessment in which depression was present, the nurse identified any ongoing antidepressant therapy, formulated pharmacologic and/or nonpharmacologic treatment recommendations using evidence–based treatment algorithms that were developed for the SMILE Trial, and discussed the treatment options and their recommendations with the patient (21,22). If the patient accepted the recommendations, the nurse contacted the patient’s renal provider to discuss the proposed treatment and if accepted, helped implement the recommended therapy.

For each monthly assessment in which depression was identified, we tracked and recorded patients’ acceptance of nurses’ treatment recommendations as well as reasons for nonacceptance on the basis of verbal feedback from the patient at the time of the assessment. In cases in which the recommended treatment was accepted by the patient, we tracked provider agreement to implement the treatment as well as their reasons for not accepting the recommendation. Unless otherwise specified, antidepressant treatment refers to pharmacologic and/or nonpharmacologic therapy.

Statistical Analyses

We used descriptive statistics to characterize the prevalence of depression, use of pharmacologic and/or nonpharmacologic antidepressant treatments, patients’ acceptance of nurses’ treatment recommendations, reasons for patient nonacceptance of recommendations, provider acceptance of recommended therapy, and providers’ reasons for nonacceptance of recommended therapy. We depict data at the level of the monthly assessment rather than at the level of the patient given the longitudinal assessment of depression and the relatively small number of patients overall. Given the likelihood of correlation of responses regarding preferences for treatment within individual patients, we used a random effects model to assess the intraclass correlation coefficient for patients’ refusal to modify or initiate treatment. We also describe the proportion of patients who did not accept a treatment recommendation on at least one monthly assessment and all monthly assessments as well as the proportion of patients who accepted all treatment recommendations. We used random effects logistic regression to evaluate patient characteristics associated with patient refusal of treatment recommendations.

Results

Baseline Patient Characteristics and Depression Assessments

Of 220 patient participants in the SMILE Trial, 101 were randomized to the management arm, and 39 (39%) had at least one monthly PHQ-9 score ≥10. These 39 patients were our study population. There were no differences in demographic or baseline clinical characteristics between our 39 study patients and patients in the management arm who did not have at least one monthly PHQ-9 score ≥10 (data not shown). Study patients’ mean age was 64 years old, 56% were men, and 36% were black (Table 1). At baseline, 17 (44%) study patients were receiving antidepressant medication, 1 (3%) was receiving psychiatric counseling, and 21 (54%) were not receiving treatment for depression. Study patients completed a total of 373 monthly assessments over a period of up to 12 months, of which 147 (39%) revealed the presence of depression. For 103 (70%) of 147 monthly assessments in which depression was present, antidepressant medication (n=96 assessments) or psychotherapy (n=7 assessments) was being used. For 44 (30%) of 147 monthly assessments in which depression was identified, patients were not receiving antidepressant treatment.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics (n=39)

| Patient characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Age, yr, median (IQR) | 64 (54–68) |

| Men, n (%) | 22 (56) |

| Black, n (%) | 14 (36) |

| Education level, n (%) | |

| <12th Grade | 5 (13) |

| 12th Grade/high school/GED | 14 (36) |

| Greater than high school | 20 (51) |

| Employed (full or part time), n (%) | 4 (10) |

| Married or living with partner, n (%) | 16 (41) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Time on dialysis, yr, median (IQR) | 1.5 (0.5–4.1) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |

| Current smoker | 12 (31) |

| Hemodialysis access, n (%) | |

| AVF/AVG | 30 (77) |

| Catheter | 9 (23) |

| Charlson comorbidity score, n (%) | |

| 1–2 | 8 (21) |

| 3–4 | 16 (41) |

| ≥5 | 15 (38) |

IQR, interquartile range; GED, general education diploma; AVF, arteriovenous fistula; AVG, arteriovenous graft.

Patient Acceptance of Nurses’ Treatment Recommendations

Patients Receiving Antidepressant Treatment at the Time of the Monthly Assessment.

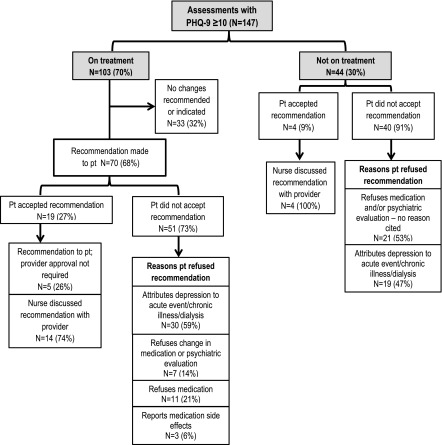

For 33 (38%) of 103 monthly assessments in which depression was identified and patients were receiving antidepressant treatment, the nurse identified no reason to modify therapy (Figure 1). For 70 (68%) of 103 monthly assessments in which depression was identified and patients were receiving antidepressant therapy, the nurse determined that the ongoing treatment was not optimally effective and recommended a modification in therapy. In five (7%) of these instances, patients accepted the nurse’s recommendation, which did not require approval by the renal provider (e.g., change in medication schedule). Patients refused nurse’s recommendations in 51 (73%) instances. Reasons why patients refused treatment recommendations included attribution of depression to a recent acute event, chronic disease, or dialysis (n=30); lack of interest in changing medication dose or undergoing additional psychiatric evaluation (n=7); refusal to take medication (n=11); and concern about medication side effects (n=3). Factors associated with patient refusal of treatment recommendations were older age (odds ratio [OR] for each 10 additional years, 1.9; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.14 to 3.19), being married (OR, 2.74; 95% CI, 0.97 to 7.72), and black race (OR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.12 to 1.09), although only the association of older age with treatment refusal was statistically significant. In 19 (27%) instances, patients accepted the treatment recommendation, and the recommendation was communicated to the renal provider in 14 (20%) instances overall (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Treatment recommendations and patient acceptance of recommendations. PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9; pt, patient.

Patients Not Receiving Antidepressant Treatment at the Time of the Monthly Assessment.

For 44 (30%) of 147 monthly assessments in which depression was identified, patients were not receiving antidepressant therapy (Figure 1). Patients did not accept nurses’ recommendations to initiate antidepressant therapy or undergo psychiatric evaluation in 40 (91%) instances. They did not cite a specific reason for refusing the recommendations in 21 (53%) of 40 instances, and they did not accept the treatment recommendations because they attributed their depression to a recent acute event, chronic disease, and/or dialysis in 19 (47%) instances. In four (9%) instances, patients accepted the treatment recommendation, which was communicated to the renal provider (Figure 1). Patients reported suicidal ideation on the PHQ-9 on six monthly assessments, and recommendations were immediately made to the renal physician independent of the patient’s expressed interest in treatment.

Provider Acceptance of Treatment Recommendations

Overall, the research nurse asked renal providers to consider a treatment recommendation for 18 monthly assessments, of which the providers accepted seven (39%) and did not accept 11 (61%) (Table 2). In eight of 11 instances, the renal provider offered no explanation for not accepting the recommendation; in two instances, the renal provider deferred treatment recommendations to the patients’ primary care provider, and in one instance, the provider did not accept the recommendation because the patient was hospitalized.

Table 2.

Provider acceptance of treatment recommendations

| Recommendation | Accepted, n=7 (39%) | Not Accepted, n=11 (61%) |

|---|---|---|

| Increase dose | 1 | 3 |

| Change medication | 1 | 0 |

| Start or add new medication | 2 | 2 |

| Referral to/follow-up with psychiatry | 3 | 3 |

| Medication and psychiatry referral | 0 | 3 |

Correlation of Responses within Patients

Study patients had a median number of three (interquartile range, 1–5) monthly assessments with a PHQ-9 score ≥10. Thirty of 39 (77%) patients had five or fewer monthly PHQ-9 scores ≥10. The intraclass correlation measuring the intrapatient correlation of responses not accepting treatment recommendations was 0.36. Of 39 study patients, 30 (77%) did not accept nurses’ treatment recommendations on at least one occasion, 15 (38%) did not accept any recommendations, and nine (23%) accepted all recommendations.

Discussion

Our study shows that depression is detectable in approximately 40% of patients on chronic HD over the course a year. In many instances, patients either are receiving antidepressant therapy that may be ineffective or are not receiving antidepression therapy at all. Patients with depression often choose not to accept evidence-based recommendations to modify or initiate therapy, frequently attributing their depressive illness to an acute event, chronic illness, or dialysis itself. In rare instances in which patients wish to modify or initiate treatment, renal providers infrequently implement such therapy. These findings highlight important obstacles to the routine implementation of antidepressant therapy in this patient population.

On many assessments, we found that patients were receiving antidepressant treatment that seemed to be potentially ineffective on the basis of the presence of scores on the PHQ-9 of ≥10, whereas on a smaller but notable number of assessments, patients were not receiving any therapy. In certain patients, antidepressant therapy may have recently been initiated without sufficient time to gauge effectiveness. However, antidepressant treatment may have been inadequately alleviating this symptom in many instances. In fact, the proportion of assessments with a PHQ-9 score ≥10 was comparable among patients receiving treatment at the beginning of the study and those not receiving treatment at the beginning of the study (38% versus 41%, respectively). Although small studies have documented the efficacy of antidepressant medications and cognitive behavioral therapy in patients on chronic HD, our findings suggest the possibility that depression might be more situational and potentially less amenable to standard treatment in some patients (16–19). This possibility is suggested by our finding that patients commonly attribute their depression to an acute illness. Interesting, a very recent trial by Angermann et al. (23) of 372 patients with heart failure and depression found that esitalopram did not improve all-cause mortality, hospitalization, or depression severity at 18 months compared with placebo. Although this trial enrolled patients with heart failure, it raises questions about the efficacy of antidepressant therapy in patients with chronic diseases in general. Adequately powered clinical trials that examine the effect of antidepressant treatment on depression severity, quality of life, and mortality are clearly needed in the ESRD population (24).

Very commonly, our patients with depression rejected recommendations to modify existing treatment or initiate novel therapy. Patients’ lack of interest in antidepressant therapy was previously documented in a study by Wuerth et al. (25), in which <50% of patients on peritoneal dialysis with depressive symptoms agreed to testing to confirm the presence of depression and receive treatment. The principal reasons that our patients cited for rejecting nurses’ recommendations included attribution of their depression to a recent acute event, chronic illness, or HD itself; lack of interest in taking medication or undergoing psychiatric evaluation; and concern about medication side effects. Patients on chronic HD consume a median of 19 medications daily (26). Hence, polypharmacy may explain patients’ reluctance to receive pharmacologic antidepressant therapy. Patients on chronic HD may also not fully appreciate that depression is an actual illness that is potentially treatable with pharmacologic and/or nonpharmacologic interventions. Efforts to educate patients about depression and various potential treatment options may mitigate their reluctance to accept therapy for this condition.

Similarly revealing was our finding that renal providers commonly refuse to implement treatment for depression. Although nurses’ recommendations for treatment only reached renal providers in 18 instances, providers refused the recommendation for most patients and rarely offered an explanation for their refusal. We previously reported that many renal providers believe that it is the responsibility of nonrenal providers to treat depression (27). However, past research showed that 90% of nephrologists provided primary care to their patients on dialysis and that as few as 20% of patients on chronic dialysis have a separate primary care provider (28,29). The apparent unwillingness of renal providers to consider implementing treatment for depression, particularly in the absence of primary providers who might assume this responsibility, represents a major obstacle to the systematic provision of therapy.

The potential significance of our findings is magnified when viewed in the context of the recently released criteria from the CMS for the ESRD QIP for payment year 2018, which mandates that dialysis facilities report documentation of screening and treatment plans for depression in each patient (15). Several prior QIP measures were implemented as reporting requirements and subsequently, transformed into clinical performance measures used in the value–based payment system. The implementation of a performance measure on the basis of screening and treatment of depression in patients on chronic dialysis would logically be on the basis of the assumptions that treatment is effective and that patients wish to have this condition treated. The results of this study suggest that this latter assumption may be incorrect. Until there is evidence that the systematic screening and treatment of depression are parts of a process that patients derive benefit from and accept, the requirement to universally document and/or provide such care may be premature.

Our study has several limitations. First and foremost, our study population was small, which limited the statistical power and precluded robust patient–level analyses. Therefore, we opted to analyze our data at the level of the monthly assessment, which introduced the issue of correlation within patients with regard to preferences for treatment. Although we found moderate correlation of responses (rho=0.36), most of our patients (77%) refused nurses’ recommendations on at least one occasion. Second, our patients were participants in a clinical trial and may not be representative of the broader HD population. For example, our study patients were receiving antidepressant therapy in 70% of monthly assessments in which we identified the presence of depression. This is higher than has been seen in prior studies and may reflect the fact that patients were participating in a symptom management trial. Third, our finding that antidepressive treatment may be ineffective in many instances is on the basis of data from our patients with depression who were already receiving treatment. It is possible that patients may not have had PHQ-9 scores consistent with depression, because treatment for this condition was effective. However, we did evaluate the use of antidepressant therapy among the 62 patients in the management arm with no monthly assessments showing depression and found that just 15 (24%) were prescribed antidepressant medication at any time during the study. Fourth, the small number of recommendations that reached renal providers limited the generalizability of the findings regarding their willingness to implement treatment. Fifth, recommendations for antidepressant treatment were generated by trained research nurses who were not members of the dialysis team. Thus, patients and providers may have been less willing to accept their recommendations than if proposed by dialysis team members. Sixth, although we use the term depression to characterize patients with PHQ-9 scores ≥10, the PHQ-9 assesses depressive symptoms, not depressive disorders. Research nurses discussed the significance of the PHQ-9 score with patients but did not formally diagnose a depressive disorder. Thus, our findings are applicable to patient and provider preferences for treatment related to the presence of depressive symptoms.

In conclusion, among patients receiving chronic HD, the prevalence of depression is high, and patients seem to be frequently ineffectively treated or not treated at all. Patients often reject evidence-based recommendations to modify or initiate antidepressant therapy, attributing their depression to a recent acute event, chronic illness, or dialysis itself. Providers are commonly reluctant to implement treatment for this condition. These novel findings highlight major obstacles to the routine implementation of antidepressant therapy in this patient population and underscore the strong need for additional data on the effectiveness of antidepressant therapy and methods to address patient and provider nonacceptance of treatment before mandates to universally screen and treat this patient population are implemented.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

Because P.M.P. was a Deputy Editor of the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology at the time of peer-review, he was not involved in the peer review process for this manuscript. Another editor oversaw the peer review and decision-making process for this manuscript.

This work was supported by Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Merit Review award IIR 07-190 (to S.D.W.).

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US Government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “We Need to Talk about Depression and Dialysis: but What Questions Should We Ask, and Does Anyone Know the Answers?,” on pages 222–224.

References

- 1.Hedayati SS, Finkelstein FO: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of depression in patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 54: 741–752, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kimmel PL, Cukor D, Cohen SD, Peterson RA: Depression in end-stage renal disease patients: A critical review. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 14: 328–334, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopes AA, Bragg J, Young E, Goodkin D, Mapes D, Combe C, Piera L, Held P, Gillespie B, Port FK; Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) : Depression as a predictor of mortality and hospitalization among hemodialysis patients in the United States and Europe. Kidney Int 62: 199–207, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watnick S, Kirwin P, Mahnensmith R, Concato J: The prevalence and treatment of depression among patients starting dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 41: 105–110, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watnick S, Wang PL, Demadura T, Ganzini L: Validation of 2 depression screening tools in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 46: 919–924, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Arnold RM, Fine MJ, Levenson DJ, Peterson RA, Switzer GE: Prevalence, severity, and importance of physical and emotional symptoms in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 2487–2494, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimmel PL: Psychosocial factors in adult end-stage renal disease patients treated with hemodialysis: Correlates and outcomes. Am J Kidney Dis 35[Suppl 1]: S132–S140, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kimmel PL, Emont SL, Newmann JM, Danko H, Moss AH: ESRD patient quality of life: Symptoms, spiritual beliefs, psychosocial factors, and ethnicity. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 713–721, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimmel PL, Peterson RA: Depression in end-stage renal disease patients treated with hemodialysis: Tools, correlates, outcomes, and needs. Semin Dial 18: 91–97, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weisbord SD, McGill JB, Kimmel PL: Psychosocial factors in patients with chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 14: 316–318, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belayev LY, Mor MK, Sevick MA, Shields AM, Rollman BL, Palevsky PM, Arnold RM, Fine MJ, Weisbord SD: Longitudinal associations of depressive symptoms and pain with quality of life in patients receiving chronic hemodialysis. Hemodial Int 19: 216–224, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cruz LN, Fleck MP, Polanczyk CA: Depression as a determinant of quality of life in patients with chronic disease: Data from Brazil. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 45: 953–961, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cukor D, Rosenthal DS, Jindal RM, Brown CD, Kimmel PL: Depression is an important contributor to low medication adherence in hemodialyzed patients and transplant recipients. Kidney Int 75: 1223–1229, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lopes AA, Lantz B, Morgenstern H, Wang M, Bieber BA, Gillespie BW, Li Y, Painter P, Jacobson SH, Rayner HC, Mapes DL, Vanholder RC, Hasegawa T, Robinson BM, Pisoni RL: Associations of self-reported physical activity types and levels with quality of life, depression symptoms, and mortality in hemodialysis patients: The DOPPS. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1702–1712, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: End-Stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Program Payment Year 2018 Final Measure Technical Specifications, 2016. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/ESRDQIP/Downloads/PY-2018-Technical-Measure-Specifications.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2016

- 16.Blumenfield M, Levy NB, Spinowitz B, Charytan C, Beasley CM Jr., Dubey AK, Solomon RJ, Todd R, Goodman A, Bergstrom RF: Fluoxetine in depressed patients on dialysis. Int J Psychiatry Med 27: 71–80, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cukor D, Ver Halen N, Asher DR, Coplan JD, Weedon J, Wyka KE, Saggi SJ, Kimmel PL: Psychosocial intervention improves depression, quality of life, and fluid adherence in hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 196–206, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duarte PS, Miyazaki MC, Blay SL, Sesso R: Cognitive-behavioral group therapy is an effective treatment for major depression in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 76: 414–421, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levy NB, Blumenfield M, Beasley CM Jr., Dubey AK, Solomon RJ, Todd R, Goodman A, Bergstrom RR: Fluoxetine in depressed patients with renal failure and in depressed patients with normal kidney function. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 18: 8–13, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weisbord SD, Mor MK, Green JA, Sevick MA, Shields AM, Zhao X, Rollman BL, Palevsky PM, Arnold RM, Fine MJ: Comparison of symptom management strategies for pain, erectile dysfunction, and depression in patients receiving chronic hemodialysis: A cluster randomized effectiveness trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 90–99, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weisbord SD, Shields AM, Mor MK, Sevick MA, Homer M, Peternel J, Porter P, Rollman BL, Palevsky PM, Arnold RM, Fine MJ: Methodology of a randomized clinical trial of symptom management strategies in patients receiving chronic hemodialysis: The SMILE study. Contemp Clin Trials 31: 491–497, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barakzoy AS, Moss AH: Efficacy of the world health organization analgesic ladder to treat pain in end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 3198–3203, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Angermann CE, Gelbrich G, Störk S, Gunold H, Edelmann F, Wachter R, Schunkert H, Graf T, Kindermann I, Haass M, Blankenberg S, Pankuweit S, Prettin C, Gottwik M, Böhm M, Faller H, Deckert J, Ertl G; MOOD-HF Study Investigators and Committee Members : Effect of escitalopram on all-cause mortality and hospitalization in patients with heart failure and depression: The MOOD-HF randomized clinical trial. JAMA 315: 2683–2693, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hedayati SS, Daniel DM, Cohen S, Comstock B, Cukor D, Diaz-Linhart Y, Dember LM, Dubovsky A, Greene T, Grote N, Heagerty P, Katon W, Kimmel PL, Kutner N, Linke L, Quinn D, Rue T, Trivedi MH, Unruh M, Weisbord S, Young BA, Mehrotra R: Rationale and design of a trial of sertraline vs. cognitive behavioral therapy for end-stage renal disease patients with depression (ASCEND). Contemp Clin Trials 47: 1–11, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wuerth D, Finkelstein SH, Ciarcia J, Peterson R, Kliger AS, Finkelstein FO: Identification and treatment of depression in a cohort of patients maintained on chronic peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 37: 1011–1017, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiu YW, Teitelbaum I, Misra M, de Leon EM, Adzize T, Mehrotra R: Pill burden, adherence, hyperphosphatemia, and quality of life in maintenance dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1089–1096, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green JA, Mor MK, Shields AM, Sevik MA, Palevsky PM, Fine MJ, Arnold RM, Weisbord SD: Renal provider perceptions and practice patterns regarding the management of pain, sexual dysfunction, and depression in hemodialysis patients. J Palliat Med 15: 163–167, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nespor SL, Holley JL: Patients on hemodialysis rely on nephrologists and dialysis units for maintenance health care. ASAIO J 38: M279–M281, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shah N, Dahl NV, Kapoian T, Sherman RA, Walker JA: The nephrologist as a primary care provider for the hemodialysis patient. Int Urol Nephrol 37: 113–117, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]