Abstract

Background and objectives

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is widely prevalent among patients on hemodialysis (HD), but very rarely treated. The aim of our study is to evaluate the burdens of HCV suffered by patients on HD.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study is an international, prospective, cohort study of patients on HD. We reviewed the HCV status of 76,689 adults enrolled between 1996 and 2015. We compared HCV-positive (HCV+) with HCV-negative (HCV−) patients for risk of mortality, hospitalization, decline in hemoglobin concentration <8.5 g/dl, and red blood cell transfusion. We also compared health-related quality of life scores using the Kidney Disease Quality of Life instrument and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Short Depression Scale. We adjusted for age, sex, race, years on dialysis, 14 comorbid conditions (including hepatitis B infection), and serum albumin, phosphorus, and creatinine concentrations.

Results

A total of 7.5% of patients were HCV+ at enrollment. Serum concentrations of alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase were not markedly elevated in HCV+ patients on HD; the mean concentrations were only 22.6 and 21.8 U/L, respectively. Median follow-up was 1.4 years. Case-mix adjusted hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) for HCV+ versus HCV− patients were 1.12 (1.05 to 1.20) for all-cause mortality, 5.90 (3.67 to 9.50) for hepatic-related mortality, 1.09 (1.04 to 1.13) for all-cause hospitalization, and 4.40 (3.14 to 6.15) for hepatic-related hospitalization. Quality of life measures indicated significantly worse scores for physical function, pain, vitality, mental health, depression, pruritus, and anorexia among HCV+ patients. The adjusted hazard ratio for transfusion was 1.36 (95% CI, 1.20 to 1.55) and incidence of hemoglobin concentration <8.5 g/dl was 1.12 (95% CI, 1.03 to 1.21). Only 1.5% of HCV+ patients received antiviral medication.

Conclusions

HCV infection among patients on HD is associated with higher risk of death, hospitalization, and anemic complications, and worse quality of life scores. Internationally, HCV infection is almost never treated in patients on HD. Our data provide a rationale for more frequent treatment of HCV in this population.

Keywords: Hepatitis C, mortality, quality of life, anemia, renal dialysis, Adult, Anorexia, Antiviral Agents, creatinine, depression, Epidemiologic Studies, Erythrocyte Transfusion, Follow-Up Studies, Hemoglobins, Hepacivirus, Hepatitis B, hospitalization, Humans, Incidence, Kidney Diseases, Mental, Health, Pain, Phosphorus, Prevalence

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is common among patients on hemodialysis (HD) worldwide, with a prevalence of 9.5% having been reported previously (1). Nosocomial HCV spread within HD facilities continues to occur, according to viral sequencing and epidemiologic evidence (2). Previous studies have reported increased mortality associated with HCV but the potential links between HCV and hospitalization, anemia, or quality of life among patients on HD remain unclear. The goal of this investigation is to study the burden of HCV infection among patients on HD enrolled in the very large, international Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) (3,4).

Materials and Methods

Patients and Data Collection

The DOPPS is an international prospective cohort study of patients on HD aged ≥18 years. Patients in the DOPPS are enrolled randomly from a representative sample of dialysis facilities within each nation at the start of each study phase, as described previously (3,4).

Data from 76,689 patients on HD from Australia, Belgium, Canada, China, France, Germany, six Gulf Cooperation Council Countries (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and United Arab Emirates), Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Spain, Russia, Sweden, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States with baseline information on HCV status were included in this study. Phase 1 of the DOPPS collected data from 1996 to 2001; phase 2 collected data from 2002 to 2004; phase 3 collected data from 2005 to 2008; phase 4 collected data from 2009 to 2011; and phase 5 collected data from 2012 to 2015. Data collection in Australia, Belgium, Canada, New Zealand, and Sweden did not begin until phase 2. Data collection in China, the Gulf Cooperation Council countries, Russia, and Turkey did not begin until phase 5. Study approval was obtained by a central institutional review board. Patient consent was obtained as required by national and local ethics committee regulations.

Demographic data, comorbid conditions, laboratory values, and medications were abstracted from patient records. Medication prescriptions were collected at entry and every 4 months during phases 1, 3, 4, and 5, and at entry and once yearly during phase 2. To examine the use of anti-HCV medications, we searched the prescription database for both proprietary and generic drug names of formulations of IFN and ribavirin, as well as the following new, oral agent terms: Daklinza (daclatasvir), Harvoni (ledipasvir, sofosbuvir), Incivek (telaprevir), Olysio (simeprevir), Sovaldi (sofosbuvir), Sovriad (simeprevir), Sunvepra (asunaprevir), Technivie (ombitasvir, paritaprevir), Victrelis (boceprevir), Viekira Pak (dasabuvir, ombitasvir, paritaprevir), Zepatier (ebasvir, grazoprevir). HCV status was determined on the basis of an established diagnosis of HCV infection or positive HCV serology at DOPPS enrollment. Thereafter, HCV serology was collected every 4 months in phase 1, yearly in phase 2, and monthly in phases 3–5. Mortality and hospitalization events were collected during study follow-up. Patient-reported measures were collected from self-reported questionnaires at study enrollment during each phase. Health-related quality of life was assessed using the Kidney Disease Quality of Life (KDQOL-36) instrument and summarized for the Physical Component Summary (PCS), Mental Component Summary (MCS), and Kidney Disease Burden scores (5). Responses to specific questions about pruritus and lack of appetite were analyzed separately. Self-reported depression was assessed in DOPPS phases 2–5 via the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Short Depression Scale (CES-D-10) (6).

Data Analyses

The primary exposure of interest was HCV status at study enrollment. Standard descriptive statistics were used to characterize the patient samples.

Models.

Cox regression was used to analyze the association between HCV status and the outcomes of mortality, first hospitalization, occurrence of hemoglobin <8.5 g/dl, red blood cell transfusion, or gastrointestinal bleed during study follow-up. Models were stratified by country and phase, accounting for facility clustering using robust sandwich covariance estimators.

Time at risk started at study enrollment and ended at the time of death, 7 days after leaving the facility because of transplant or transfer, 7 days after changing modality, loss to follow-up, or at of the end of data collection.

To model the associations between HCV status and patient-reported measures, mixed models for linear outcomes and generalized estimating equation models with a logit link for binary outcomes were used, accounting for facility clustering.

Variables adjusted for as potential confounders are listed in the table footnotes for each model.

Multiple Imputation.

Missing data for covariates was low (e.g., <5% for the majority of covariates, <14% for all). For missing data, we used the Sequential Regression Multiple Imputation Method implemented by IVEware (Imputation and Variance Estimation Software), and analyzed using the MIAnalyze procedure in SAS/STAT v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Table 1 shows the characteristics of HCV-positive (HCV+) and HCV-negative (HCV−) patients at time of enrollment into the DOPPS. Among the full sample of 76,689 patients, 5762 (7.5%) were HCV+. The prevalence of HCV infection among the initial cross-sections of patients enrolled in each phase of the study varied as follows (restricted to those countries that participated in all five phases): 14.3% in phase 1, 10.7% in phase 2, 8.8% in phase 3, 6.8% in phase 4, and 8.7% in phase 5. Compared with HCV− patients, the HCV+ patients were younger; had spent more years on dialysis; more frequently had GN or vasculitis as the primary cause of ESRD; had lower prevalences of hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, lung disease, cerebrovascular disease, and cancer; and had higher prevalences of hepatitis B and substance abuse. Cirrhosis was notably more common among HCV+ patients (9.9%) than HCV− patients (1.4%). Cirrhosis was present among 10.0% of HCV+ patients who were hepatitis B–negative versus 9.2% of HCV+ patients who were hepatitis B–positive; thus, cirrhosis among HCV+ patients was predominantly not because of coinfection with hepatitis B virus. Also, serum creatinine concentration was higher among HCV+ patients and platelet count was lower.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by DOPPS region and HCV status at study enrollment (DOPPS phases 1–5, 1996–2015)

| Characteristic | Overall | North America | Europea | Japan | Otherb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCV+ | HCV− | HCV+ | HCV− | HCV+ | HCV− | HCV+ | HCV− | HCV+ | HCV− | |

| Patients, n | 5762 | 70,927 | 1732 | 27,740 | 1846 | 25,526 | 1480 | 10,457 | 704 | 7204 |

| Demographics | ||||||||||

| Age, yr | 58.5 (13.6) | 62.8 (15.0) | 56.1 (13.2) | 62.3 (15.4) | 58.9 (14.6) | 64.3 (15.0) | 62.3 (11.4) | 62.5 (12.9) | 54.8 (13.9) | 59.2 (15.0) |

| Men, % | 62.2 | 58.4 | 66.8 | 55.0 | 57.1 | 60.7 | 65.3 | 62.7 | 57.3 | 57.1 |

| Black race, % | — | — | 52.1 | 26.9 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yr on dialysis | 4.6 [1.1, 12.8] | 1.6 [0.3, 4.6] | 2.1 [0.3, 5.5] | 1.2 [0.2, 3.6] | 5.9 [1.4, 15.8] | 1.4 [0.3, 4.3] | 7.9 [2.2, 18.5] | 3.5 [0.6, 8.4] | 6.3 [2.4, 12.7] | 2.3 [0.7, 4.9] |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.3 (5.1) | 25.6 (6.1) | 25.5 (5.9) | 27.5 (6.9) | 23.6 (4.5) | 25.5 (5.2) | 20.3 (3.0) | 21.1 (3.3) | 23.3 (5.5) | 25.1 (6.0) |

| Transplant waitlisted, %c | 11.7 | 10.7 | 16.3 | 11.0 | 15.2 | 13.0 | 6.5 | 4.2 | 6.9 | 10.7 |

| Primary cause of ESRD, % | ||||||||||

| GN or vasculitis | 32.0 | 21.5 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 31.3 | 20.3 | 50.3 | 44.3 | 37.9 | 27.6 |

| Cystic/hereditary/congenital | 6.4 | 6.4 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 12.4 | 9.5 | 3.0 | 5.4 | 6.6 | 6.9 |

| Diabetes | 25.2 | 32.4 | 35.0 | 42.6 | 14.4 | 22.3 | 29.3 | 32.1 | 20.3 | 29.8 |

| Obstruction | 4.0 | 3.5 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 8.6 | 5.9 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 4.0 | 4.7 |

| Interstitial nephritis | 3.1 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 5.2 | 5.3 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 2.8 | 4.2 |

| Hypertension | 16.1 | 20.1 | 33.9 | 28.9 | 9.7 | 17.7 | 3.3 | 5.4 | 17.1 | 16.8 |

| Other cause of ESRD | 12.2 | 10.6 | 8.8 | 6.9 | 16.8 | 15.4 | 11.4 | 9.6 | 10.4 | 8.8 |

| Comorbidities, % | ||||||||||

| Hypertension | 75.3 | 82.9 | 86.5 | 87.6 | 75.6 | 82.1 | 63.2 | 73.4 | 79.4 | 86.4 |

| Coronary artery disease | 33.4 | 41.5 | 44.4 | 53.2 | 30.3 | 38.9 | 30.4 | 27.7 | 27.5 | 39.3 |

| Neurologic disorder | 10.3 | 10.1 | 14.0 | 11.8 | 10.6 | 10.3 | 7.5 | 7.6 | 8.5 | 8.7 |

| Other cardiovascular disease | 31.9 | 31.2 | 27.2 | 32.2 | 37.1 | 34.2 | 34.1 | 26.2 | 21.9 | 25.3 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 20.5 | 25.2 | 21.7 | 29.4 | 23.2 | 28.0 | 18.9 | 13.8 | 14.7 | 20.4 |

| Diabetes | 32.0 | 40.1 | 44.8 | 53.3 | 23.4 | 32.6 | 33.9 | 35.7 | 27.3 | 36.9 |

| Congestive heart failure | 25.5 | 30.2 | 36.8 | 43.0 | 24.8 | 26.1 | 17.3 | 18.9 | 23.9 | 26.5 |

| Lung disease | 8.6 | 11.8 | 13.3 | 16.1 | 10.7 | 12.6 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 6.1 | 10.4 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 13.1 | 16.2 | 15.8 | 18.3 | 12.8 | 16.0 | 12.7 | 13.9 | 10.0 | 14.9 |

| Recurrent cellulitis | 6.3 | 7.8 | 9.8 | 10.5 | 6.9 | 7.8 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 5.0 | 6.7 |

| Cancer | 9.8 | 12.4 | 9.3 | 12.9 | 11.3 | 15.0 | 11.0 | 8.6 | 3.9 | 7.2 |

| Gastrointestinal bleed in last yr | 6.2 | 5.4 | 8.7 | 7.1 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 6.1 | 4.3 | 4.8 | 3.8 |

| Psychologic disorder | 18.6 | 16.6 | 35.2 | 24.4 | 21.8 | 17.0 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 10.5 | 11.8 |

| Substance abuse in last 12 mo | 5.1 | 1.7 | 17.9 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| Cirrhosisd | 9.9 | 1.4 | 11.7 | 1.6 | 10.1 | 1.5 | 14.4 | 1.3 | 6.3 | 1.0 |

| Hepatitis B | 8.4 | 1.8 | 5.7 | 0.9 | 10.5 | 1.8 | 5.6 | 1.9 | 13.8 | 4.3 |

| HIV/AIDS | 2.8 | 0.6 | 7.7 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.1 |

| Laboratory values | ||||||||||

| Hb, g/dl | 10.8 (1.7) | 10.9 (1.6) | 11.1 (1.7) | 11.0 (1.5) | 11.2 (1.7) | 11.1 (1.6) | 10.0 (1.4) | 10.1 (1.4) | 10.9 (2.0) | 10.9 (1.8) |

| Albumin, g/dl | 3.7 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.5) | 3.6 (0.6) | 3.7 (0.5) | 3.8 (0.6) | 3.7 (0.6) | 3.7 (0.4) | 3.7 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.5) |

| Ferritin, ng/ml | 285 [110, 570] | 330 [141, 625] | 422 [200, 728] | 431 [197, 757] | 309 [151, 553] | 327 [163, 567] | 97.2 [39.0, 224.0] | 95.0 [37.0, 212.0] | 343 [133, 640] | 393 [190, 654] |

| CRP, mg/le | 3.3 [1.0 ,9.0] | 5.0 [1.6, 12.0] | — | — | 5.0 [3.0, 13.0] | 6.4 [3.0, 15.2] | 1.0 [0.5, 3.8] | 1.0 [0.5, 3.3] | 4.2 [2.0, 8.5] | 5.3 [2.5, 14.0] |

| Phosphorus, mg/dl | 5.4 (1.8) | 5.4 (1.7) | 5.5 (1.8) | 5.4 (1.8) | 5.2 (1.8) | 5.2 (1.8) | 5.5 (1.6) | 5.5 (1.5) | 5.6 (2.3) | 5.5 (1.9) |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 9.4 (3.1) | 8.5 (3.2) | 9.1 (3.6) | 8.0 (3.2) | 8.7 (2.8) | 8.0 (2.8) | 10.2 (2.8) | 10.4 (3.1) | 9.8 (3.1) | 9.1 (3.2) |

| Platelets, 103 cells/mm3d | 169 (86) | 199 (87) | 195 (80) | 214 (76) | 195 (75) | 220 (78) | 97.6 (81.6) | 119 (101) | 173 (76) | 198 (74) |

| Bilirubin, mg/dlf | 0.6 (2.0) | 0.5 (1.6) | 0.5 (0.2) | 0.5 (1.1) | 0.5 (1.0) | 0.6 (2.2) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.9 (3.0) | 0.5 (0.4) |

| ALT, U/Lf | 22.6 (31.6) | 16.4 (22.6) | 21.4 (12.4) | 16.7 (21.0) | 23.8 (19.4) | 18.4 (30.0) | 18.7 (59.2) | 11.5 (10.2) | 24.8 (17.0) | 16.7 (13.1) |

| AST, U/Lf | 21.8 (16.0) | 17.3 (16.4) | 23.8 (12.5) | 18.4 (13.1) | 21.1 (11.7) | 18.3 (20.8) | 19.3 (23.2) | 14.7 (13.7) | 23.2 (13.5) | 16.3 (12.1) |

| Medications | ||||||||||

| ESA prescription in last mo, % | 82.4 | 84.0 | 83.3 | 82.9 | 81.9 | 84.3 | 80.8 | 83.6 | 84.7 | 87.5 |

| Epoetin equivalent dose, U/wkg | 7500 [4232, 12,695] | 8279 [4600, 13,800] | 12,000 [6000, 24,000] | 11,500 [6000, 22,800] | 7359 [4232, 12,500] | 7500 [4600, 12,500] | 5000 [2760, 8279] | 4761 [2760, 8279] | 9000 [5750, 11,500] | 9199 [5980, 12,000] |

| ESA dose:Hb ratio, (U/wk)/ (g/dl) | 708 [387, 1233] | 750 [411, 1304] | 1043 [513, 2195] | 1020 [500, 2026] | 667 [367, 1165] | 692 [403, 1163] | 476 [285, 812] | 463 [276, 806] | 833 [505, 1237] | 841 [505, 1223] |

| IV iron prescription in last 4 mo, % | 45.3 | 53.7 | 48.8 | 51.8 | 59.0 | 65.7 | 24.1 | 25.8 | 44.6 | 58.0 |

| IV iron dose, mg/mog | 250 [160, 435] | 250 [174, 435] | 250 [200, 500] | 272 [213, 625] | 250 [150, 435] | 250 [160, 435] | 174 [160, 348] | 174 [160, 348] | 435 [217, 489] | 254 [157, 435] |

Results shown as prevalence, mean (SD), or median [interquartile range]. DOPPS, Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HCV+, hepatitis C virus-positive; HCV−, hepatitis C virus-negative; —, not measured; Hb, hemoglobin; CRP, C-reactive protein; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ESA, erythropoiesis stimulating agent; IV, intravenous.

Includes Belgium, Italy, France, Germany, Spain, Sweden, and United Kingdom.

Includes Australia (2002–2015), China (2010–2015), Gulf Cooperation Council countries (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and United Arab Emirates, 2012–2015), New Zealand (2002–2015), Russia (2012–2015), and Turkey (2012–2015).

DOPPS phase 1 (1996–2001) only collected in the United States; also collected in all other countries in subsequent phases.

DOPPS phases 4 and 5 only (2009–2015), n=30,030 patients.

Restricted to facilities measuring CRP routinely (quarterly) for at least 75% of patients (excludes all North American facilities); not collected in DOPPS phase 1 (1996–2001).

DOPPS phase 5, year 2+ only (2013–2015); first nonmissing value during DOPPS phase 5 follow-up; n=6083, 7968, and 9214 for bilirubin, AST, and ALT respectively.

Among patients prescribed (excludes zero doses); darbepoetin doses converted at 250:1, PEGylated epoetin β (Mircera) doses converted at 208:1, subcutaneous doses converted at 1.15:1.

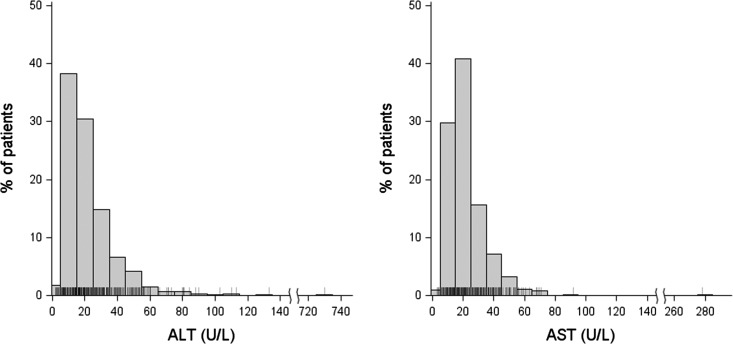

Table 1 shows that serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) concentrations were higher among HCV+ patients than HCV− patients, although mean values were still within the normal ranges. Figure 1 shows the distribution of transaminase concentrations among HCV+ patients during phase 5, the only phase when ALT and AST were measured. Most values are within the normal range or slightly elevated. Only one HCV+ patient had ALT elevation >140 U/L and only one HCV+ patient had AST elevation >100 U/L.

Figure 1.

ALT and AST concentrations are within normal limits or only minimally elevated among HCV+ patients (phase 5, 2012–2015). For ALT: n=677 patients; mean±SD: 23±32 U/L; only one patient with ALT>140 U/L. For AST: n=613 patients; mean±SD: 22±16 U/L; only one patient with AST>100 U/L. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; HCV+, hepatitis C virus-positive.

Mortality

Patients were followed for a median of 1.4 years. The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for HCV+ versus HCV− patients was 1.12 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.05 to 1.20) for all-cause mortality, and 5.90 (95% CI, 3.67 to 9.50) for death because of a hepatic cause (Table 2). The HRs of infectious death and of cardiovascular death did not reach statistical significance, but each showed a tendency toward higher rates in HCV+ patients.

Table 2.

Mortality for HCV+ versus HCV− patients (DOPPS phases 1–5, 1996–2015)

| Event | No. of Events | Crude Ratea | Unadjusted HRb (95% CI) | Adjusted HRc (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause mortality | 15,807 | 139.5 | 1.02 (0.95 to 1.09) | 1.12 (1.05 to 1.20)d |

| Cardiovascular | 6790 | 65.8 | 0.97 (0.87 to 1.07) | 1.10 (0.98 to 1.22) |

| Infection | 2187 | 21.2 | 1.05 (0.88 to 1.27) | 1.11 (0.91 to 1.34) |

| Hepatic-relatede | 113 | 1.1 | 5.88 (3.84 to 8.99)d | 5.90 (3.67 to 9.50)d |

n=73,577 patients included in all-cause models. n=65,015 patients included in cause-specific models as large United States dialysis organizations in DOPPS phases 4 and 5 were excluded because of differential reporting of cause of mortality. Facilities reporting zero deaths during DOPPS follow-up or having <5 cumulative patient-years of mortality follow-up were excluded. HCV+, hepatitis C virus-positive; HCV−, hepatitis C virus-negative; DOPPS, Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Events per 1000 patient years.

Stratified by DOPPS country (United States black and nonblack patients considered as separate strata) and phase and accounting for facility clustering.

Stratified by DOPPS country (United States black and nonblack patients considered as separate strata) and phase and accounting for facility clustering; adjusted for age, sex, time on dialysis, 13 summary comorbidities and hepatitis B infection, and albumin, phosphorus, and creatinine levels.

P<0.05.

Includes hepatitis, cirrhosis, or liver failure as primary or secondary cause of death.

Among the HCV+ patients, serum ALT concentration >70 U/L (greater than twice the upper limit of normal; n=15) was associated with significant risk of mortality compared with patients with lower ALT concentrations, with an adjusted HR of 4.30 (95% CI, 1.33 to 13.89). Comparing HCV+ patients with a value above the 90th percentile for ALT (n=62 with ALT>41 U/L) or AST (n=59 with AST>39 U/L) with a reference group consisting of patients in the 50th–75th percentiles resulted in adjusted mortality HRs of 2.41 (95% CI, 1.26 to 4.63) and 3.95 (95% CI, 2.13 to 7.33), respectively.

Hospitalization

The adjusted HR for HCV+ patients versus HCV− patients was 1.09 (95% CI, 1.04 to 1.13) for all-cause hospitalization; 4.40 (95% CI, 3.14 to 6.15) for hepatic-related hospitalization; 1.10 (95% CI, 1.03 to 1.17) for cardiovascular hospitalization; and 1.08 (95% CI, 1.00 to 1.18) for infection-related hospitalization (Table 3).

Table 3.

Hospitalization events for HCV+ versus HCV− patients (DOPPS phases 1–5, 1996–2015)

| Hospitalization Type | No. of Events | Crude Ratea | Unadjusted HRb (95% CI) | Adjusted HRc (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause hospitalization | 38,895 | 626.7 | 1.06 (1.02 to 1.11)d | 1.09 (1.04 to 1.13)d |

| Cardiovasculare | 14,525 | 187.2 | 1.04 (0.98 to 1.11) | 1.10 (1.03 to 1.17)d |

| Stroke | 2074 | 23.3 | 0.97 (0.83 to 1.13) | 1.08 (0.92 to 1.27) |

| Myocardial infarction | 2208 | 24.8 | 0.97 (0.82 to 1.15) | 1.05 (0.88 to 1.25) |

| Infectionf | 9597 | 116.4 | 1.07 (0.99 to 1.16) | 1.08 (1.00 to 1.18) |

| Sepsis | 2592 | 29.3 | 1.05 (0.89 to 1.23) | 1.06 (0.90 to 1.25) |

| Pneumonia | 2209 | 24.9 | 1.14 (0.97 to 1.33) | 1.15 (0.98 to 1.35) |

| Hepatic-relatedg | 231 | 2.6 | 5.51 (4.09 to 7.44)d | 4.40 (3.14 to 6.15)d |

n=71,743 patients included in all-cause models. n=63,377 patients included in cause-specific models as large United States dialysis organizations in DOPPS phases 4 and 5 were excluded because of differential reporting of hospitalization cause. Facilities reporting zero hospitalizations during DOPPS follow-up or having <5 cumulative patient-years of hospitalization follow-up were excluded. HCV+, hepatitis C virus-positive; HCV−, hepatitis C virus-negative; DOPPS, Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

First-hospitalization events (per 1000 patient years).

Stratified by DOPPS country (United States black and nonblack patients considered as separate strata) and phase and accounting for facility clustering.

Stratified by DOPPS country (United States black and nonblack patients considered as separate strata) and phase and accounting for facility clustering; adjusted for age, sex, time on dialysis, 13 summary comorbidities and hepatitis B infection, and albumin, phosphorus, and creatinine levels.

P<0.05.

Includes stroke and myocardial infarction among other cardiovascular-related hospitalizations.

Includes sepsis and pneumonia among other infection-related hospitalizations.

Includes hospitalizations with diagnosis of viral hepatitis or ascites, or liver biopsy procedure.

Outcomes Associated with Anemia

Among those patients who entered the study with hemoglobin concentration ≥8.5 g/dl, the adjusted HR of a subsequent decline <8.5 g/dl for HCV+ patients versus HCV− patients was 1.12 (95% CI, 1.03 to 1.21), 1.36 (95% CI, 1.20 to 1.55) for blood transfusion, and 1.32 (95% CI, 1.13 to 1.54) for gastrointestinal bleeding (Table 4).

Table 4.

Anemia-related events for HCV+ versus HCV− patients (DOPPS phases 1–5, 1996–2015)

| Event | No. of Events | Crude Ratea | Unadjusted HRb (95% CI) | Adjusted HRc (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin <8.5 g/dld | 8615 | 112.3 | 1.10 (1.02 to 1.19)e | 1.12 (1.03 to 1.21)e |

| Transfusionf | 3268 | 49.9 | 1.31 (1.15 to 1.48)e | 1.36 (1.20 to 1.55)e |

| Gastrointestinal bleedg | 2093 | 23.6 | 1.28 (1.10 to 1.48)e | 1.32 (1.13 to 1.54)e |

HCV+, hepatitis C virus-positive; HCV−, hepatitis C virus-negative; DOPPS, Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

First-events (hemoglobin <8.5 g/dl, transfusion, gastrointestinal bleed) (per 1000 patient years).

Stratified by DOPPS country (United States black and nonblack patients considered as separate strata) and phase and accounting for facility clustering.

Stratified by DOPPS country (United States black and nonblack patients considered as separate strata) and phase and accounting for facility clustering; adjusted for age, sex, time on dialysis, 13 summary comorbidities and hepatitis B infection, and albumin, phosphorus, and creatinine levels.

n=60,319 patients; restricted to patients with baseline hemoglobin ≥8.5 g/dl.

P<0.05.

n=48,253 patients; excludes DOPPS phase 1 where transfusions were not included as an option on the hospitalization worksheet. In phases 2 and 3, transfusions were only ascertained on the hospitalization worksheet (as inpatient or outpatient events); in phases 4 and 5, transfusion events were additionally captured every month on the interval summary; however, dialysis units may not be aware of or record all blood transfusions that patients receive when transfusions occur in a hospital. Large United States dialysis organizations in DOPPS phases 4 and 5 did not provide transfusion events.

n=63,377 patients; large United States dialysis organizations in DOPPS phases 4 and 5 were excluded because of differential reporting of hospitalization cause. Facilities reporting zero hospitalizations during DOPPS follow-up or having <5 cumulative patient-years of hospitalization follow-up were excluded.

Quality of Life

The KDQOL-36 instrument was administered at entry into the DOPPS. Quality of life scores were significantly inferior for patients with HCV infection across all eight domains, on both the PCS and MCS, and also for Kidney Disease Burden score (Table 5). HCV+ patients were more likely to be moderately to extremely bothered by pruritus (rather than somewhat bothered or not at all bothered) than HCV− patients (Table 6). Similarly, HCV+ patients were significantly more likely to be moderately to extremely bothered by anorexia.

Table 5.

Patient-reported measures for HCV+ versus HCV− patients (DOPPS phases 1–5, 1996–2015): Linear regression models

| Quality of Life Measure (Higher=Better) | Outcome Mean | Unadjusted Difference (95% CI)a | Adjusted Difference (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| KDQOL-36 Physical Component Summaryc,d | 36.5 | −1.2 (−1.5 to −0.8)e | −0.9 (−1.2 to −0.5)e |

| Physical functioning | 41.8 | −2.9 (−4.0 to −1.7)e | −2.8 (−3.8 to −1.7)e |

| Role-physical | 38.0 | −2.0 (−3.2 to −0.9)e | −2.1 (−3.2 to −0.9)e |

| Bodily pain | 59.6 | −5.6 (−6.6 to −4.6)e | −3.8 (−4.8 to −2.8)e |

| General health | 40.9 | −3.3 (−4.1 to −2.5)e | −2.6 (−3.5 to −1.8)e |

| KDQOL-36 Mental Component Summaryc,d | 44.7 | −1.2 (−1.6 to −0.8)e | −1.2 (−1.6 to −0.8)e |

| Vitality | 38.8 | −2.4 (−3.3 to −1.5)e | −2.3 (−3.2 to −1.4)e |

| Social functioning | 58.3 | −2.5 (−3.5 to −1.5)e | −1.9 (−3.0 to −0.9)e |

| Role-emotional | 54.1 | −2.7 (−3.9 to −1.4)e | −3.3 (−4.5 to −2.0)e |

| Mental health | 62.8 | −2.9 (−3.7 to −2.2)e | −2.2 (−3.0 to −1.5)e |

| KDQOL-36 Kidney Disease Burdenc,d | 36.7 | −1.8 (−2.6 to −1.0)e | −2.1 (−3.0 to −1.3)e |

HCV+, hepatitis C virus-positive; HCV−, hepatitis C virus-negative; DOPPS, Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; KDQOL-36, Kidney Disease Quality of Life instrument.

Adjusted for DOPPS country (United States black and nonblack patients considered separately) and phase and accounting for facility clustering.

Additionally adjusted for age, sex, time on dialysis, 13 summary comorbidities and hepatitis B infection, and albumin, phosphorus, and creatinine levels.

Parameter estimates from linear mixed models represent the modeled difference between HCV+ versus HCV− patients (n=44,320 patients; the models for the subscales had additional patients that did not complete all of the questions necessary to calculate the summary scores, n=50,771–53,576); n=53,596 patients completed the Kidney Disease Burden questions.

Physical and mental component summary and kidney disease burden scores calculated from the KDQOL-36; Lower kidney disease burden score indicates more kidney disease burden. Parameter estimate is from a linear mixed model and represents the modeled difference between HCV+ and HCV− patients (n=44,320 patients).

P<0.05.

Table 6.

Patient-reported measures for HCV+ versus HCV− patients (DOPPS phases 1–5, 1996–2015): Logistic regression models

| Outcome Measure (Lower=Better) | Outcome Prevalence, % | Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI)a | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depressionc | 44.1 | 1.28 (1.17 to 1.40)d | 1.27 (1.16 to 1.40)d |

| Prurituse | 40.6 | 1.24 (1.16 to 1.33)d | 1.27 (1.18 to 1.36)d |

| Lack of appetitef | 23.2 | 1.25 (1.16 to 1.35)d | 1.22 (1.12 to 1.32)d |

HCV+, hepatitis C virus-positive; HCV−, hepatitis C virus-negative; DOPPS, Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Adjusted for DOPPS country (United States black and nonblack patients considered separately)and phase and accounting for facility clustering.

Additionally adjusted for age, sex, time on dialysis, 13 summary comorbidities and hepatitis B infection, and albumin, phosphorus, and creatinine levels.

Odds ratio from a logistic model for a Center for Epidemiologic Studies Short Depression Scale (CES-D-10) score ≥10 (versus <10) for HCV+ versus HCV− patients (n=34,035 patients); not collected in DOPPS phase 1 (1996–2001).

P<0.05.

Odds ratio for moderately to extremely bothered by itchiness for HCV+ versus HCV− patients (n=52,469 patients).

Odds ratio for moderately to extremely bothered by lack of appetite for HCV+ versus HCV− patients (n=52,185 patients).

The CES-D-10 questionnaire was also administered at study entry, consisting of ten questions with scores of 0–3. A total score of ≥10 may be considered indicative of symptoms of depression (7). As shown in Table 6, the odds ratio of having a CES-D-10 score ≥10 (versus <10) was 1.27 (1.16 to 1.40) when comparing HCV+ patients with HCV– patients.

Prescription of HCV Antiviral Medication

Tables 7 and 8 delineate the numbers of patients treated for HCV infection by country, phase, and medication type. Only 1.5% of patients were treated (80 of 5313 HCV+ patients with prescription data in phases 1–5). Prescription of direct acting oral agents was particularly rare. Data from 2012 to the present (phase 5 and the initial months of phase 6) reveal that only 11 patients (seven in the United States and one each in Australia, Canada, France, and Sweden) have been treated with any of the new drugs.

Table 7.

Antiviral treatment of HCV+ patients by DOPPS country and phase (1996–2015)

| Region/Country | DOPPS Phasea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Australia/New Zealand | — | 0 (27) | 0 (17) | 0 (26) | 1 (16) |

| Belgium | — | 0 (43) | 0 (27) | 1 (31) | 1 (26) |

| Canada | — | 0 (26) | 1 (29) | 0 (24) | 2 (31) |

| China | — | — | — | 1 (102) | 1 (58) |

| France | 4 (112) | 0 (84) | 3 (66) | 1 (44) | 1 (6) |

| Gulf Cooperation Council | — | — | — | — | 4 (113) |

| Germany | 0 (32) | 1 (26) | 3 (25) | 3 (21) | 1 (41) |

| Italy | 1 (154) | 1 (139) | 2 (99) | 0 (76) | 2 (60) |

| Japan | 0 (498) | 0 (288) | 0 (276) | 1 (188) | 2 (208) |

| Russia | — | — | — | — | 0 (46) |

| Spain | 0 (152) | 2 (92) | 4 (74) | 3 (82) | 2 (84) |

| Sweden | — | 1 (33) | 1 (32) | 1 (35) | 2 (41) |

| Turkey | — | — | — | — | 0 (11) |

| United Kingdom | 0 (15) | 1 (13) | 0 (6) | 1 (17) | 0 (20) |

| United States | 16 (618) | 0 (218) | 2 (136) | 4 (297) | 2 (252) |

| All DOPPS countries | 21 (1581) | 6 (989) | 16 (787) | 16 (943) | 21 (1013) |

Expressed as n treated at enrollment or during follow-up (N HCV+ patients at enrollment); antiviral treatment defined as IFN, ribavirin, or new oral direct Hepatitis C virus inhibitor prescription; medications collected every 4 months in DOPPS phases 1, 3–5, and once yearly in DOPPS phase 2. HCV+, hepatitis C virus-positive; DOPPS, Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study; —, not yet joined DOPPS.

DOPPS phase 1 (1996–2001 in the United States, 1998–2001 in Europe/Japan); phase 2 (2002–2004); phase 3 (2005–2008); phase 4 (2009–2011); phase 5 (2012–2015).

Table 8.

Antiviral treatment regimens by DOPPS phase (1996–2015)

| Antiviral Regimen | DOPPS Phasea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| IFN only | 18 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 5 |

| Ribavirin only | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| IFN and ribavirin | 3 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 9 |

| Oral direct HCV inhibitor only | — | — | — | — | 1 |

| Oral direct HCV inhibitor and IFN/ribavirin | — | — | — | — | 5 |

| Total prescriptions | 21 | 6 | 16 | 16 | 21 |

Expressed as n treated at enrollment or during follow-up among HCV+ patients at enrollment; medications collected every 4 months in DOPPS phases 1, 3–5, and once yearly in DOPPS phase 2. DOPPS, Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study; —, oral direct HCV inhibitors not available; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

DOPPS phase 1 (1996–2001 in the United States, 1998–2001 in Europe/Japan); phase 2 (2002–2004); phase 3 (2005–2008); phase 4 (2009–2011); phase 5 (2012–2015).

Discussion

In 1999 it was reported that HCV infection had become the most common chronic blood-borne infection in the United States (8). Guidelines from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases in 2015 state that evidence clearly supports the treatment of all patients infected with HCV, except those with life expectancy <12 months because of comorbid conditions (9). These guidelines further recommend that, optimally, therapy should be given early in the course of infection, before liver fibrosis progression and advancement to complications, although the most immediate benefits will accrue to those at highest risk of hepatic complications. In the general population, HCV infection is associated with a 12-fold higher age-adjusted mortality rate (10). Between 1996 and 2010 there were >4 million hospitalizations at 500 hospitals in the United States among patients with HCV, and the rate increased during that period (11). HCV infection is also associated with inferior scores on quality of life testing (12,13). Patients who attain sustained viral response (SVR) after antiviral treatment achieve improvements in quality of life scores on various scales, including fatigue, activity, energy, work impairment, and nonwork activity impairment (14,15).

The goal of the present investigation was to study the consequences of HCV infection in patients on HD. Previous studies have reported significantly higher case-mix adjusted risks of mortality comparing HCV+ with HCV− patients on HD, with HRs ranging from 1.25 to 1.97 (16–21). However, four of these studies included <300 HCV+ patients. In contrast, the DOPPS is a very large, multinational study with more extensive adjustments for demographics, comorbid conditions, and laboratory parameters. As shown in Table 1, patients with HCV infection are younger, less often diabetic, and have fewer cardiovascular or malignant comorbid conditions; hence, it is very important to adjust for case-mix. Our results demonstrate an adjusted mortality HR of 1.12 (95% CI, 1.05 to 1.20) associated with HCV infection and, even more strikingly, a hepatic-related mortality HR of 5.90 (95% CI, 3.67 to 9.50). It would appear misguided to assume that patients on HD do not live long enough to succumb to the liver complications of HCV infection.

Although serum transaminase concentrations were not markedly elevated among HCV+ patients, those with higher levels within the observed ranges of values were noted to have significantly higher adjusted mortality risk. Concentrations ≥40 U/L may merit particular concern, although this finding is preliminary because of the small sample size.

HCV infection is also associated with a significantly higher risk of hospitalization. The adjusted HR for HCV+ versus HCV− status is 1.09 (95% CI, 1.04 to 1.13) and the HR for hepatic-related hospitalization is 4.40 (95% CI, 3.14 to 6.15). Cardiovascular and infectious hospitalizations are also greater among HCV+ patients.

Cirrhosis was present among 9.9% of HCV+ patients versus 1.4% of HCV− patients, and portal hypertension, hypersplenism, or coagulopathy may contribute to bleeding or shorter red blood cell lifespan. Also, platelet counts were lower. Therefore, we decided to examine whether HCV infection is associated with gastrointestinal bleeding and/or anemic sequelae. Indeed, the HRs show higher risks of a hemoglobin concentration decline to <8.5 g/dl (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.21), transfusion (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.20 to 1.55), or gastrointestinal bleeding (HR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.13 to 1.54) among HCV+ patients. Previous smaller studies have reported varying relationships between HCV infection and hemoglobin concentration, erythropoiesis stimulating agent (ESA) dose requirement, and intravenous iron dose requirement (22–25), but the larger DOPPS, with more comprehensive adjustment for case-mix, reveals no significant difference between the HCV+ and HCV− groups in baseline hemoglobin concentration, ESA dose, ESA dose/hemoglobin ratio, or intravenous iron dose.

A study of 83 HCV+ patients in Turkey found worse MCS and PCS scores and higher depression scores among HCV+ patients (26), whereas a contradictory study of 41 HCV+ patients in Iran found that scores were better on almost all KDQOL-36 items (27). In the present study, HCV infection was clearly associated with worse patient-reported outcomes across all items and both summary scales of the KDQOL-36, and also on the CES-D-10 depression instrument, both before and after adjustment for case-mix. Pruritus and anorexia are commonly experienced by individuals with kidney or liver disease, and the data show that greater proportions of patients on HD with HCV infection are moderately to extremely bothered by these two symptoms. It is interesting to note that although itching in liver disease has classically been ascribed to the accumulation of bile salts, the serum bilirubin concentration is not elevated among HCV+ patients in the DOPPS. Recently, correlations have been reported between hepatic pruritus and the presence of lysophosphatidic acid and the enzyme responsible for its formation, autotaxin (28), but these compounds were not measured in this study.

The Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcome (KDIGO) guidelines addressing HCV in CKD were issued in 2008, when IFN and ribavirin were the only therapies approved to treat HCV (29). IFN-based therapy achieved SVR in 41% of patients on HD according to a meta-analysis; comparable or superior to the efficacy in the general population (30). However, side effects such as depression, flu-like symptoms, and anemia could be troublesome, and IFN has to be administered by subcutaneous injections for at least 6 months. The guidelines state that CKD patients accepted for kidney transplantation should be treated. Risk of mortality and allograft failure are both higher among HCV+ renal transplant recipients compared with HCV− renal transplant recipients (31). KDIGO recommended that other patients with CKD should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. Yet, in 2013, we found that only 1% of HCV+ patients in the DOPPS were treated, including only 3.7% of those on renal transplantation waiting lists (1). In recent years, much improved medications for HCV have become available: oral agents that only need to be taken for 12 weeks, with near-total SVR rates and minimal side effects. Nonetheless, among 980 HCV+ patients in the DOPPS between April 2012 and December 2014, only two patients worldwide were treated with any of the novel oral agents (32). Now, reviewing more recent prescription data from DOPPS phases 5 and 6 (2012 to present), we find that only 11 patients (seven in the United States and one each in Australia, Canada, France, and Sweden) have been treated with the new drugs. A phase 3 study of patients with stage 4–5 CKD and HCV infection has shown that direct antiviral therapy, in this case a combination of the oral agents grazoprevir and elbasvir, attained 99% SVR with adverse event frequencies similar to those reported on placebo (33). The new agents were found to be efficacious, safe, and well tolerated. Preliminary analysis of quality of life results showed significant improvement in the general health domain 12 weeks after treatment compared with the placebo group.

In light of the availability of safe, effective therapy, it is uncertain why patients on HD essentially remain untreated for HCV. Literature reports of treatment rates for HCV infection are rare. We are aware of a single report that mentioned that only 49 of 545 patients on HD had received IFN for HCV infection before renal transplantation (34). Treatment rates appear to be much higher in the non-CKD population—about 22%–28% in the United States and United Kingdom (35,36). In this study, only 1.5% received antiviral therapy, whereas hundreds of thousands of patients with HCV in the general population have been prescribed the new agents. It is possible that nephrologists do not recognize that HCV induces severe liver damage in patients on HD because, unlike in the general population, serum aminotransferase concentrations often remain within the normal ranges or are only slightly elevated in this setting (37–39). In this study, the mean values for ALT and AST were only 22.6 and 21.8 U/L, respectively; only one HCV+ patient had ALT elevation >140 U/L and only one HCV+ patient had AST elevation >100 U/L.

There are limitations to our study. The DOPPS only analyzes data that are routinely collected by the participating HD facilities and does not mandate special studies. Thus, we cannot report HCV RNA concentrations, HCV genotype, liver biopsy findings, or coagulation results. Also, it is possible that the associations noted between HCV status and outcomes in this observational study are partly because of unmeasured confounding factors rather than HCV infection per se. However, in light of the findings that HCV+ patients are younger than HCV− patients, have fewer serious comorbid conditions, and have longer dialysis vintage, it seems unlikely that HCV infection is not contributing to the deleterious outcomes and worse quality of life scores. Finally, randomized clinical trials would be needed to prove that treating HCV infection will decrease the burdens associated with the infection.

In summary, it appears erroneous to assume that HCV infection among patients on HD can be ignored because these patients will not live long enough to develop undesirable consequences. HCV infection essentially goes untreated among patients on HD in 21 countries, yet it is associated with higher risks of mortality, hospitalization, liver complications, gastrointestinal bleeding, and anemia-related sequelae, as well as a variety of undesirable quality of life scores, including greater pain and worse vitality, depression, anorexia, and pruritus.

Disclosures

D.A.G. has consulted for Accelerator (Seattle, WA), ChemoCentryx, (Mountain View, CA), Omeros (Seattle, WA), Pieris (Freising, Germany), and Xenon (Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada), and is a stockholder in Cempra (Chapel Hill, NC) and Xenon. B.B., E.K., and R.L.P. have no disclosures. M.J. has consulted for Merck (Whitehouse Station, NJ). P.M. has been an investigator and consultant for AbbVie (North Chicago, IL), Bristol Myers Squibb (New York, NY), Gilead (Foster City, CA), Janssen (Beerse, Belgium), and Merck.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the scientific input by Dr. Chizoba Nwankwo and Dr. Jean Marie Arduino of Merck Sharp & Dohme for their conceptual approaches to this research investigation and interpretation of study findings.

This Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) investigation of hepatitis C has been supported by funding from Merck Sharp & Dohme to Arbor Research Collaborative for Health. Additionally, the DOPPS program is supported by Amgen, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, AbbVie, Sanofi Renal, Baxter Healthcare, and Vifor Fresenius Medical Care Renal Pharma. Additional support for specific projects and countries is provided by Keryx Biopharmaceuticals, Proteon Therapeutics, Relypsa, and F Hoffmann-LaRoche, in Canada by Amgen, BHC Medical, Inc., Janssen, Takeda, and the Kidney Foundation of Canada (for logistics support), in Germany by Hexal, Deutschen Gesellschaft fur Nephrologie, Shire, and Wissenschaftliches Institut fur Nephrologie, and for the Peritoneal Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study in Japan by the Japanese Society for Peritoneal Dialysis. All support is provided without restrictions on publications. Grants are made to Arbor Research Collaborative for Health and not to individual investigators.

Data from this manuscript have previously been published in abstract form: hepatitis C virus prevalence and clinical outcomes were reported at the meeting of the European Renal Association-European Dialysis and Transplant Association (London, England; May 29, 2015), as well as quality of life data in a separate abstract, and anemia findings were reported at the meeting of the American Society of Nephrology (San Diego, CA; November 6, 2015).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Goodkin DA, Bieber B, Gillespie B, Robinson BM, Jadoul M: Hepatitis C infection is very rarely treated among hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol 38: 405–412, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Health Advisory CDC: CDC Urging Dialysis Providers and Facilities to Assess and Improve Infection Control Practices to Stop Hepatitis C Virus Transmission in Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. 2016. Available at: http://emergency.cdc.gov/han/han00386.asp. Accessed March 14, 2016

- 3.Young EW, Goodkin DA, Mapes DL, Port FK, Keen ML, Chen K, Maroni BL, Wolfe RA, Held P: The dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study: An international hemodialysis study. Kidney Int 57: S74–S81, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pisoni RL, Gillespie BW, Dickinson DM, Chen K, Kutner MH, Wolfe RA: The dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study (DOPPS): Design, data elements, and methodology. Am J Kidney Dis 44[Suppl 2]: 7–15, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hays RD, Kallich JD, Mapes DL, Coons SJ, Carter WB: Development of the kidney disease quality of life (KDQOL) instrument. Qual Life Res 3: 329–338, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J: Two shorter forms of the CES-D depression symptoms index. J Aging Health 5: 179–193, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL: Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med 10: 77–84, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alter MJ, Kruszon-Moran D, Nainan OV, McQuillan GM, Gao F, Moyer LA, Kaslow RA, Margolis HS: The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1988 through 1994. N Engl J Med 341: 556–562, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.AASLD/IDSA HCV Guidance Panel : Hepatitis C guidance: AASLD-IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating adults infected with hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 62: 932–954, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahajan R, Xing J, Liu SJ, Ly KN, Moorman AC, Rupp L, Xu F, Holmberg SD; Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study (CHeCS) Investigators : Mortality among persons in care with hepatitis C virus infection: The Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study (CHeCS), 2006-2010. Clin Infect Dis 58: 1055–1061, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oramasionwu CU, Toliver JC, Johnson TL, Moore HN, Frei CR: National trends in hospitalization and mortality rates for patients with HIV, HCV, or HIV/HCV coinfection from 1996-2010 in the United States: A cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 14: 536, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foster GR, Goldin RD, Thomas HC: Chronic hepatitis C virus infection causes a significant reduction in quality of life in the absence of cirrhosis. Hepatology 27: 209–212, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonkovsky HL, Woolley JM; The Consensus Interferon Study Group : Reduction of health-related quality of life in chronic hepatitis C and improvement with interferon therapy. Hepatology 29: 264–270, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ware JE Jr, Bayliss MS, Mannocchia M, Davis GL; The Interventional Therapy Group : Health-related quality of life in chronic hepatitis C: Impact of disease and treatment response. Hepatology 30: 550–555, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L, Gane E, Jacobson IM, Lawitz E, Nelson D, Gerber L, Nader F, Hunt S: Effects of sofosbuvir-based treatment, with and without interferon, on outcome and productivity of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 12: 1349–1359.e13, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pereira BJG, Natov SN, Bouthot BA, Murthy BVR, Ruthazer R, Schmid CH, Levey AS: Effect of hepatitis C infection and renal transplantation on survival in end-stage renal disease. The New England Organ Bank Hepatitis C Study Group. Kidney Int 53: 1374–1381, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stehman-Breen CO, Emerson S, Gretch D, Johnson RJ: Risk of death among chronic dialysis patients infected with hepatitis C virus. Am J Kidney Dis 32: 629–634, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakayama E, Akiba T, Marumo F, Sato C: Prognosis of anti-hepatitis C virus antibody-positive patients on regular hemodialysis therapy. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1896–1902, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Espinosa M, Martin-Malo A, Alvarez de Lara MA, Aljama P: Risk of death and liver cirrhosis in anti-HCV-positive long-term haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 16: 1669–1674, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kilpatrick RD, McAllister CJ, Miller LG, Daar ES, Gjertson DW, Kopple JD, Greenland S: Hepatitis C virus and death risk in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1584–1593, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson DW, Dent H, Yao Q, Tranaeus A, Huang C-C, Han D-S, Jha V, Wang T, Kawaguchi Y, Qian J: Frequencies of hepatitis B and C infections among haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients in Asia-Pacific countries: Analysis of registry data. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 1598–1603, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdalla AH, Owda AK, Fedail H, Popovich WF, Mousa D, Al-Hawas F, Al-Sulaiman M, Al-Khader AA: Influence of hepatitis C virus infection upon parenteral iron and erythropoietin responsiveness in regular haemodialysis patients. Nephron 84: 293–294, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sahin I, Arabaci F, Sahin HA, Ilhan M, Ustun Y, Mercan R, Eminov L: Does hepatitis C virus infection increase hematocrit and hemoglobin levels in hemodialyzed patients? Clin Nephrol 60: 401–404, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altintepe L, Kurtoglu E, Tonbul Z, Yeksan M, Yildiz A, Türk S: Lower erythropoietin and iron supplementation are required in hemodialysis patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Nephrol 61: 347–351, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khurana A, Nickel AE, Narayanan M, Foulks CJ: Effect of hepatitis C infection on anemia in hemodialysis patients. Hemodial Int 12: 94–99, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Afsar B, Elsurer R, Sezer S, Ozdemir NF: Quality of life in hemodialysis patients: Hepatitis C virus infection makes sense. Int Urol Nephrol 41: 1011–1019, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rostami Z, Pezeshki ML, Abadi ASN, Einollahi B: Health related quality of life in Iranian hemodialysis patients with viral hepatitis: Changing epidemiology. Hepat Mon 2013. Available at http://hepatmon.com/9611.fulltext. Accessed March 22, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Levy C: Management of pruritus in patients with cholestatic liver disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 7: 615–617, 2011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcome : KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of Hepatitis C in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 73[Suppl 109]: S1–S99, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gordon CE, Uhlig K, Lau J, Schmid CH, Levey AS, Wong JB: Interferon treatment in hemodialysis patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis of treatment efficacy and harms. Am J Kidney Dis 51: 263–277, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fabrizi F, Martin P, Dixit V, Bunnapradist S, Dulai G: Hepatitis C virus antibody status and survival after renal transplantation: Meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J Transplant 5: 1452–1461, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goodkin DA, Bieber B: Hemodialysis patients with hepatitis C infection are not receiving the new antiviral medications. Am J Nephrol 41: 302, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roth D, Nelson DR, Bruchfeld A, Liapakis A, Silva M, Monsour H Jr , Martin P, Pol S, Londoño M-C, Hassanein T, Zamor PJ, Zuckerman E, Wan S, Jackson B, Nguyen B-Y, Robertson M, Barr E, Wahl J, Greaves W: Grazoprevir plus elbasvir in treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection and stage 4-5 chronic kidney disease (the C-SURFER study): A combination phase 3 study. Lancet 386: 1537–1545, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morales JM, Campistol JM, Domínguez-Gil B, Andrés A, Esforzado N, Oppenheimer F, Castellano G, Fuertes A, Bruguera M, Praga M: Long-term experience with kidney transplantation from hepatitis C-positive donors into hepatitis C-positive recipients. Am J Transplant 10: 2453–2462, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts K, Macleod J, Metcalfe C, Simon J, Horwood J, Hollingworth W, Marlowe S, Gordon FH, Muir P, Coleman B, Vickerman P, Harrison GI, Waldron C-A, Irving W, Hickman M: Hepatitis C - Assessment to Treatment Trial (HepCATT) in primary care: Study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials 17: 366, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chan K, Lai MN, Groessl EJ, Hanchate AD, Wong JB, Clark JA, Asch SM, Gifford AL, Ho SB: Cost effectiveness of direct-acting antiviral therapy for treatment-naive patients with chronic HCV genotype 1 infection in the veterans health administration. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 11: 1503–1510, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guh J-Y, Lai Y-H, Yang C-Y, Chen S-C, Chuang W-L, Hsu T-C, Chen H-C, Chang W-Y, Tsai J-H: Impact of decreased serum transaminase levels on the evaluation of viral hepatitis in hemodialysis patients. Nephron 69: 459–465, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fabrizi F, Lunghi G, Finazzi S, Colucci P, Pagano A, Ponticelli C, Locatelli F: Decreased serum aminotransferase activity in patients with chronic renal failure: Impact on the detection of viral hepatitis. Am J Kidney Dis 38: 1009–1015, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Contreras AM, Ruiz I, Polanco-Cruz G, Monteón FJ, Celis A, Vázquez G, Gómez-Herrera E, García-Correa JE, Male-Velázquez R, Ruelas-Hernández S: End-stage renal disease and hepatitis C infection: Comparison of alanine aminotransferase levels and liver histology in patients with and without renal damage. Ann Hepatol 6: 48–54, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]