Abstract

Introduction:

Radiation-induced heart disease (RIHD) is a serious side effect of cancer treatment, including coronary artery disease, valvular cardiac dysfunction, cardiomyopathy, aortopathy, and chronic constrictive pericarditis. Herein, this case we present was diagnosed as radiation-induced constrictive pericarditis and cardiomyopathy by means of cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) and transthoracic echocardiogram, finally confirmed by pathology after performing heart transplant operation.

Conclusions:

This case supports a notion that RIHD often causes multiple heart impairment and CMR is helpful to diagnose cardiomyopathy after radiation.

Keywords: diagnosis and treatment, heart failure, radiation-induced heart disease

1. Introduction

Radiation-induced heart disease (RIHD) is becoming an increasing concern for patients and clinicians as the use of radiation therapy for the treatment of certain malignancies increases. With the improvement of survival rate of cancer patients, RIHD become a thorny disease that should threaten their long-term survival. So we report a rarely case of late onset RIHD including constrictive pericarditis and cardiomyopathy.

2. Case presentation

A 57-year-old woman was referred to our hospital with exertional dyspnea, edema in lower extremities, fatigue, hydrothorax, and ascites over the past 1.5 years. She had a history of radiotherapy of 4200 rad Cobalt-60 without chemotherapy after radical operation of left breast cancer 22 years ago. Blood was drawn with the following results: c (NT-proBNP) was 3200 pg/mL (normal value <300 pg/mL), and cardiac troponin (TnI) was negative. Also, antoantibodies, tuberculosis antibody, and PPD skin test were negative. Blood sedimentation was 11 mm/h (normal value 0–20 mm/h).

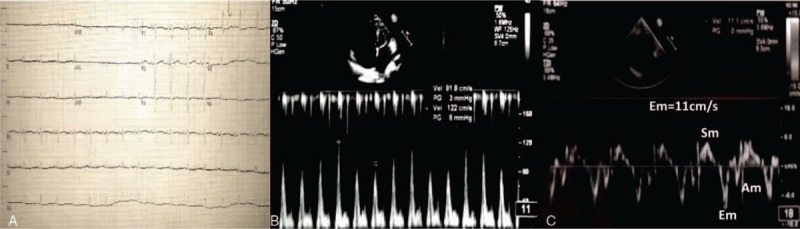

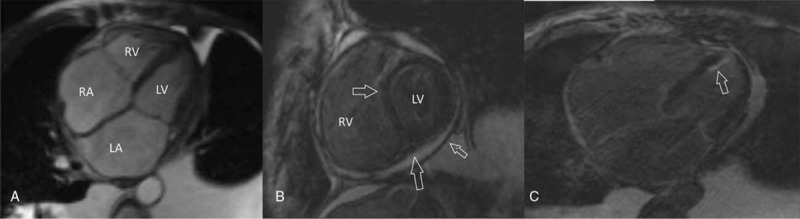

Electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm, lower voltage of limb leads, QTc prolongation(508 ms), and ST-T segment changes on leads II, III, aVF, and V4 through V6 (Fig. 1A). With normal cardiac silhouette, bilateral pulmonary congestion, middle pleural effusion, and partial pericardial thickening had been found but pericardial calcification was absent in chest X-ray and cardiac computed tomography. Furthermore, cardiac computed tomography showed no coronary stenosis. Transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a nondilated left ventricle with normal LV ejection fraction (68%), involving marked respiratory variation that was a 34% increase of mitral E velocity during expiration (Fig. 1B). Lateral mitral annular movement that was assessed on tissue Doppler imaging showed diastolic velocities (Em) were at lower normal limit (11 cm/s), although normal range is more than 8 to 10 cm/s (Fig. 1C). The 4-chamber view of cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) demonstrated biatrial enlargement (Fig. 2A). A small amount of pericardial effusion and thickened pericardial layers were seen (Fig. 2B, arrow). There was late gadolinium-enhancement (LGE) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of biventricular subendocardial part walls and mid-myocardial layer consistent with fibrosis (Fig. 2B and C, arrow).

Figure 1.

A, Electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm, lower voltage of limb leads, QTc prolongation (508 ms) and ST-T segment changes on leads II, III, aVF, and V4 through V6. B, Transthoracic echocardiogram revealed marked respiratory variation that was a 34% increase of mitral E velocity during expiration. C, Lateral Mitral annular movement that assessed on tissue Doppler imaging showed diastolic velocities (Em) was at lower normal limit (11 cm/s).

Figure 2.

A, The 4-chamber view of CMR demonstrated biatrial enlargement. B, A small amount of pericardial effusion and thickened pericardial layers were seen. B, C, There was LGE-MRI of biventricular subendocardial part walls and mid-myocardial layer consistent with fibrosis. CMR = cardiac magnetic resonance, LGE = late gadolinium enhancement, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

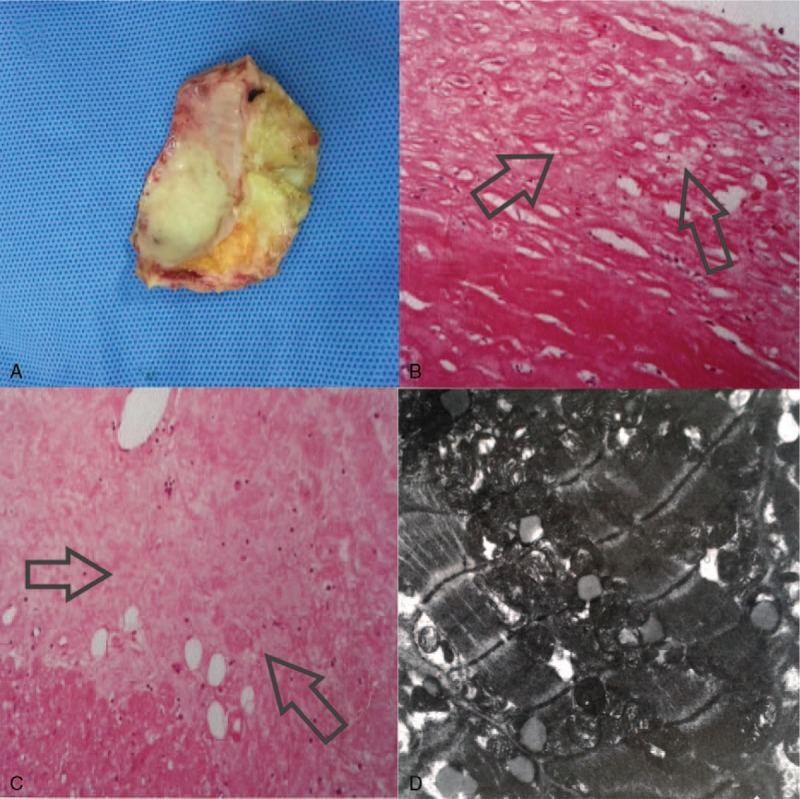

Furthermore, considering that diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis in comorbidity with cardiomyopathy, the woman underwent a heart transplant operation. During the surgery a segment of pericardium was resected (7.0 × 4.5 × 0.5 cm) (Fig. 3A) and histological examination with hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed chronic fibrinous pericarditis (Fig. 3B). From heart pathology there were just a few atheromatous plaques existing in proximal of left anterior descending branch and intact valve, whereas some white tough tissues were partly in place from biventricular endocardium to myocardium section nearby epicardium which was clarified as focal interstitial fibrosis in hematoxylin and eosin staining (Fig. 3C). Electron microscope demonstrated that increasing quantity of mitochondrial, lipofuscin, and lipid droplet of myocardial cells without cellular necrosis, some mitochondrial swelled and ridge disappeared as well as vacuolar degeneration (Fig. 3D). Finally, she was diagnosed as constrictive pericarditis in comorbidity with cardiomyopathy. Without any complaint of dyspnea or edema, the patient has been in NYHA class II and has regularly taken some antirejection drugs for 2 years since she recovered from posttransplantation.

Figure 3.

A, During the surgery a segment of pericardium was resected (7.0 × 4.5 × 0.5 cm). B, Histological examination with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed chronic fibrinous pericarditis (×100). C, Some white tough tissue were partly in place of from biventricular endocardium to myocardium section nearby epicardium which was clarified as focal interstitial fibrosis in H&E staining (×100). D, Electron microscope demonstrated that increasing quantity of mitochondrial, lipofuscin, and lipid droplet of myocardial cells without cellular necrosis, some mitochondrial swelled and ridge disappeared as well as vacuolar degeneration.

3. Discussion

RIHD generally occurs with a latent period of 10 to 15 years and is of special concern, especially in younger patients as they survive longer.[1] Our case has begun to present symptom until 22 years later, and RIHD was threatening her life instead of breast cancer itself. RIHD is including coronary artery disease, valvular cardiac dysfunction, cardiomyopathy, aortopathy, and chronic constrictive pericarditis. Radiation-induced pericardial disease is one of the most common manifestations of RIHD and occurs if a significant proportion of heart (>30%) receives a dose of 5000 rad. Fibrosis is a common cause of radiotherapy and leads to fibrous thickening of the pericardium.[2] So mitral orifice flow spectrum by Doppler echocardiography and cardiac pathological findings of this case are consistent with radiation-induced chronic constrictive pericarditis.

Radiation-induced cardiomyopathy is due to microvascular injury, which leads to ischemia and myocyte replacement by fibrosis. Although radiation-induced myocardial dysfunction includes limited regional wall-motion abnormalities, lowered LV systolic function, impaired myocardial relaxation, and diastolic dysfunction, the presence of diffuse myocardial fibrosis in radiation-induced myocardial injury is more likely to impair diastolic function.[3] Mitral lateral Em on behalf of diastolic function in our case was 11 cm/s, a little faster than that in restrictive cardiomyopathy (lower than 6–8 cm/s). It may be resulted from dyspnea exacerbated by pleural effusion. In patients with obstructive airways disease or increased respiratory effort, ventricular interaction occurs and Em can be high.[4]

As we know, vessel disease, valvular disease, and pericarditis can be treated separately by coronary artery bypass grafting, valve replacement, and pericardiectomy. However, patients with radiation-induced cardiomyopathy represent a difficult treatment dilemma with a paucity of organs for transplantation. A number of these patients have to be confronted with failed medical therapy due to end-stage cardiac disease.[5] Consequently, diagnosis of radiation-induced cardiomyopathy is of great concern, and it is usually obtained either by endomyocardial biopsy or at autopsy with interstitial fibrosis and necrosis in myocardium. LGE-MRI enables visualization of the myocardial scar in patients with ischemic and nonischemic myocardial diseases. Only 1 report that radiation-induced myocardial fibrosis observed by LGE-MRI has been published.[6] In our case, final pathology supported the LGE-MRI finding and diagnosis of radiation-induced cardiomyopathy. Thus, it was of importance to perform LGE-MRI to understand the myocardium damage and confirm the diagnosis of cadiomyopathy due to radiation, which probably taking place of endomyocardial biopsy.

Acknowledgment

Thanks for this patient who consented to publish her case.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CMR = cardiac magnetic resonance, LGE = late gadolinium–enhancement, NT-proBNP = N-terminal-pro-brain natriuretic peptide, RIHD = radiation-induced heart disease.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Andratschke N, Maurer J, Molls M, et al. Late radiation-induced heart disease after radiotherapy. Clinical importance, radiobiological mechanisms and strategies of prevention. Radiother Oncol 2011;100:160–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Madan R, Benson R, Sharma D, et al. Radiation induced heart disease: pathogenesis, management and review literature. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst 2015;27:187–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lancellotti P, Nkomo VT, Badano LP, et al. Expert consensus for multi-modality imaging evaluation of cardiovascular complications of radiotherapy in adults. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;14:721–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Syed FF, Schaff HV, Oh JK. Constrictive pericarditis-a curable diastolic heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 2014;11:530–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Saxena P, Joyce LD, Daly RC, et al. Cardiac transplantation for radiation-induced cardiomyopathy: the mayo clinic experience. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;98:2115–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Umezawa R, Ota H, Takanami K, et al. Mri findings of radiation-induced myocardial damage in patients with oesophageal cancer. Clin Radiol 2014;69:1273–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]