Abstract

Biliverdin reductase IXβ (BLVRB) is a crucial enzyme in heme metabolism. Recent studies in humans have identified a loss-of-function mutation (Ser111Leu) that unmasks a fundamentally important role in hematopoiesis. We have applied experimental and thermodynamic modeling studies to provide further insight into role of the cofactor in substrate accessibility and protein folding properties regulating BLVRB catalytic mechanisms. Site-directed mutagenesis with molecular dynamic (MD) simulations establish the critical role of NAD(P)H-dependent conformational changes on substrate accessibility by forming the “hydrophobic pocket”, along with identification of a single key residue (Arg35) modulating NADPH/NADH selectivity. Loop80 and Loop120 block the hydrophobic substrate binding pocket in apo BLVRB (open), while movement of these structures after cofactor binding results in the “closed” (catalytically active) conformation. Both enzymatic activity and thermodynamic stability are affected by mutation(s) involving Ser111 which is located in the core of the BLVRB active site. This work (1) elucidates the crucial role of Ser111 in enzymatic catalysis and thermodynamic stability by active site hydrogen bond network, (2) defines a dynamic model for apo BLVRB extending beyond the crystal structure of the binary BLVRB/NADP+ complex, (3) provides the structural basis for the “encounter” and “equilibrium” states of the binary complex which are regulated by NAD(P)H.

Keywords: biliverdin, biliverdin reductase, NADPH, short chain dehydrogenase/reductase

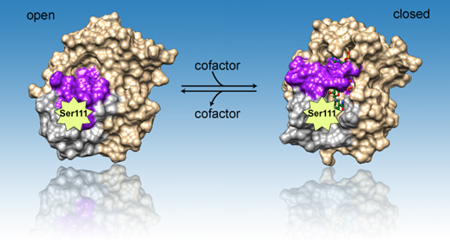

Graphical Abstract

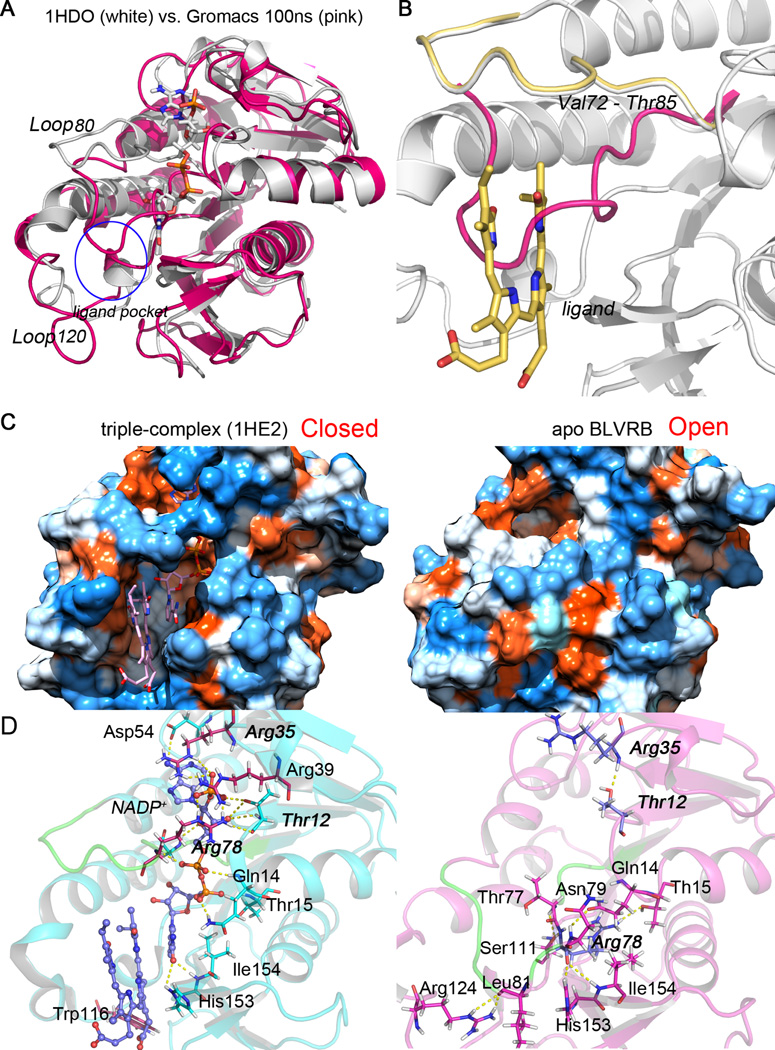

Important serine and cofactor: Both enzymatic activity and thermodynamic stability are affected by mutations involving Ser111 which is located in the core of the BLVRB active site. Binding of critical cofactor NAD(P)H removes the block of Loop80 (magenta) and Loop120 (gray) in apo BLVRB, leading to conformational change from “open” to “closed” state.

1 Introduction

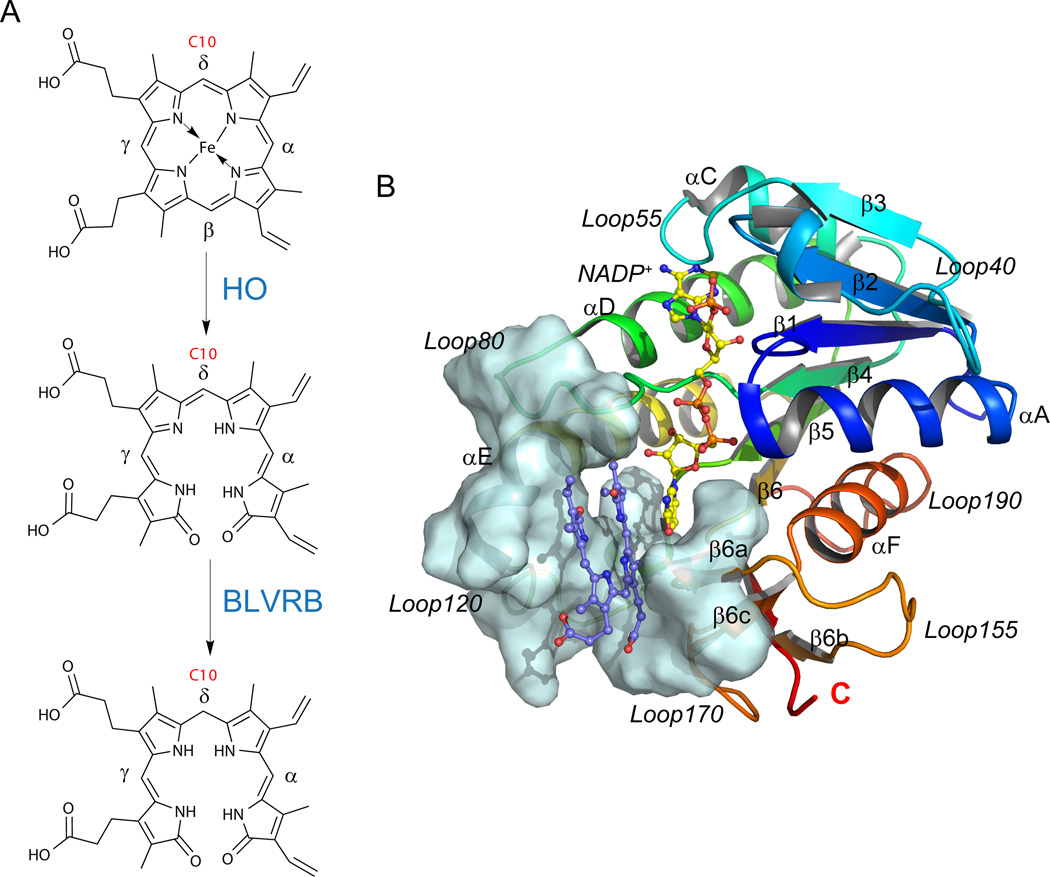

Sequential two-step catabolism of free heme generates biliverdin (BV) and bilirubin (BR) tetrapyrroles, initially by oxidative ring opening catalyzed by heme oxygenases (HO), a highly conserved family found throughout phylogeny in bacteria, algae, plants and mammals [1–3] (Fig. 1A). Although cleavage would be expected at any of the four meso bridge carbons (yielding BV isomers IXα, IXβ, IXγ, and IXδ), mammalian BVs are primarily generated by regioselective cleavage at the α-meso carbon (BV IXα), with limited identification of BV (or BR) IXβ, IXγ, or IXδ in adults. In contrast, isomeric composition appears distinct in the fetus where BR IXβ is the predominant rubin in neonatal bile, [4] although the mechanism for BV IXβ generation remains enigmatic. Mammalian bilirubin plays a major role as a physiologically significant antioxidant, and is a potential pharmacological target for treatment of neonatal jaundice [5] and organ transplantation. [6–8] In addition, low serum bilirubin is associated with a high risk of coronary artery disease.[9, 10]

Fig. 1.

BLVRB structure and its role in heme catabolism. (A) Reaction scheme of the heme degradation pathway, focusing on the step catalyzed by BLVRB. BLVRB displays a preference for biliverdin isomers without propionates straddling the C10 position (red); HO represents heme oxygenase. (B) Overall structure of the BLVRB ternary complex (PDB entry 1HE2; [12] BLVRB with NADP+ and biliverdin IXα). The active site around the substrate is shown in pale cyan surface, including a two-stranded parallel β-sheet (β6a and β6c), the N-terminus of αE helix, the flexible Loop80 and Loop120.

Two monomeric pyridine nucleotide oxidoreductases (biliverdin reductases) catalyze the reduction of the four isomers to generate the corresponding bilirubins. Both biliverdin reductases are members of the short chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) protein family [11] but retain distinct specificities for BV reduction. BVs bind in a helical, lock-washer conformation within the single α/β dinucleotide binding domain, and steric hindrance of BV IXα at the bilatriene side chain binding pocket limits its capacity for productive BLVRB interactions. [12] In humans, biliverdin reductase IXα (BLVRA) [13–15] effectively reduces BV IXα with less efficient utilization of BV IXβ, IXγ, or IXδ.[16] In contrast, biliverdin reductase IXβ (BLVRB) is promiscuous, [17, 18] catalyzing the NAD(P)H-dependent reduction of non-IXα biliverdin isomers (IXβ, IXγ, and IXδ), [19] several flavins including flavin mononucleotide (FMN), [20] pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ), [21] and ferric ion. [21] A single dinucletide binding domain accommodates both NADPH (or NADH) and substrates within the verdin/flavin (V/F) binding pocket, with no evidence to date for structural or preferred partitioning for either substrate. For the catalytic mechanism of BLVRA and BLVRB, both stepwise [5] and concerted [22] mechanisms have been proposed, with progressive support for a compulsory two-step mechanism initiated by NADPH binding.[5, 23] Thus, protonation of the pyrrolic nitrogen is the likely first step followed by hydride transfer from the nicotinamide for bilirubin formation; bulk solvent is the likely proton source with no evidence to date for alternative source(s) based on crystallographic structure and mutagenesis of candidate histidines [5, 12] or tyrosines. [24]

Despite their fundamental role(s) in heme catabolism, human disorders associated with BLVRA/BLVRB dysfunction are not described (vide infra). BLVRB function(s) remain additionally elusive because of its lack of activity towards the predominant BV IXα isomer found in adults. [12] BLVRB was initially characterized as a flavin reductase, [25] retaining physiological relevance primarily as a redox coupler in the presence of methylene blue for treatment of methemoglobinemia (CYB5A deficiency, OMIM [26] #250800). Interestingly, recent data involving a genetic screen in humans have identified a BLVRB loss-of-function redox mutation that unmasks a fundamentally important hematopoietic function with pathological development of exaggerated thrombopoiesis (platelet production). This mutation (BLVRBSer111Leu) affects both flavin and biliverdin coupling, results in enhanced generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and highlights the importance of dysregulated heme catabolism on metabolic consequences of hematopoietic speciation. [27]

In this manuscript, we have applied experimental and thermodynamic modeling studies to provide further insight into BLVRB conformational changes induced by S111 variants.[5, 12] Uniquely-generated apo BLVRB models delineate a dynamic model extending beyond the crustal structure of the binary BLVRB/NADP+ complex, thereby providing the foundation of the “encounter” and “equilibrium” states of the binary complex.[20] Loop80 and Loop120 block the hydrophobic verdin/flavin (V/F) pocket so that movement of these structures is required after cofactor binding to facilitate formation of the V/F binding site. The active site serine is located in the core of the BLVRB active site, and mutation(s) involving this residue have fundamentally discrete effects on enzymatic function and thermodynamic stability mediated by the hydrogen-bonded network.

2 Results

2.1 NAD(P)H-dependent conformational changes elucidated by molecular

modeling BLVRB binds NADPH/NADP+ approximately two orders of magnitude tighter than NADH/NAD+.[12] Recombinant BLVRB expressed and purified from lysates of Escherichia coli contains bound NADP+,[12] and all BLVRB crystal structures deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) are of complexes with NADP+ (Fig. 1B). One binary (BLVRB and NADP+ complex, PDB entry 1HDO [12]) and four ternary complex structures (with substrate or inhibitor bound, PDB entries 1HE2 to 1HE5 [12]) are available, with no structural or thermodynamic information on the apo enzyme, or its putative effects on substrate binding. SBM has been proven to be fast and informative on research pertaining to protein folding, binding, and assemblies.[28–35] It can provide many physical properties related to kinetic and thermodynamic processes of proteins.

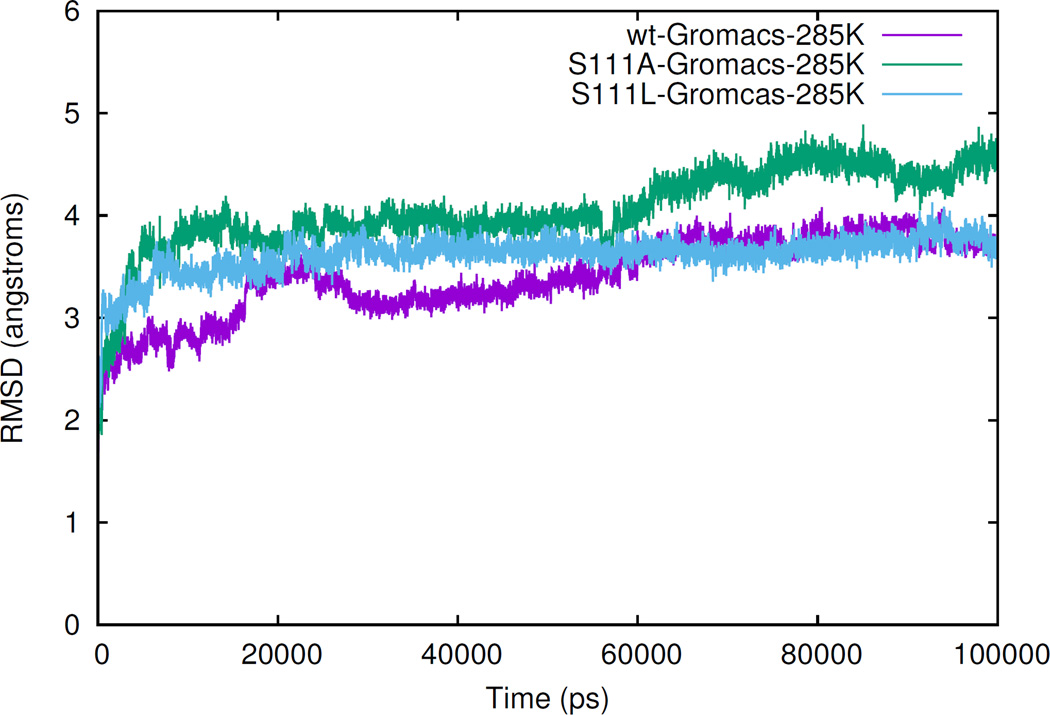

To prepare for structure-based model (SBM) simulation while simultaneously characterizing the structural role of NADPH, we completed a 100 ns simulation of apo BLVRB, apo Ser111Leu, and apo Ser111Ala to obtain the stable structure(s) lacking the cofactor. After 100 ns simulations, all three systems have reached equilibrium as noted by the nearly flat trajectory of the last 30 ns of the RMSD (root-mean-square deviation) trace (Fig. 2); indeed, the apo BLVRB RMSD of ~ 3.8 Å indicates large conformational changes between the NADP+-bound and apo forms of BLVRB.

Fig. 2.

Root-mean-square deviation curves. Simulated Cα RMSD curves of 100 ns simulations of apo wild-type, apo Ser111Ala, and apo Ser111Leu systems, with respect of the complex structure 1HDO. [12]

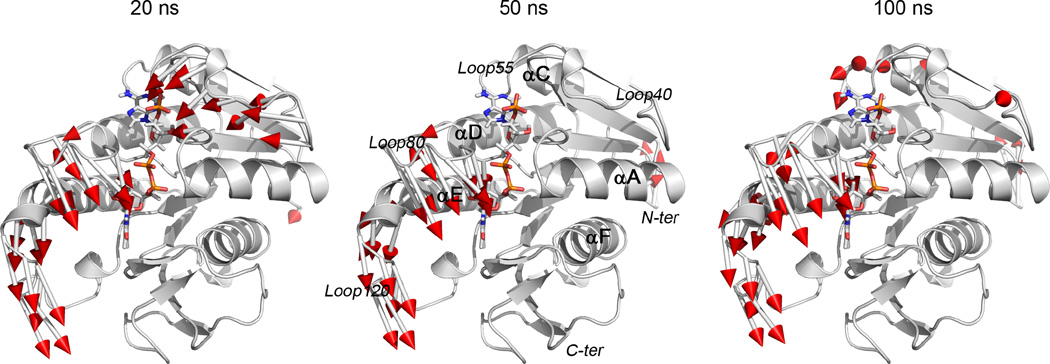

Three frames (20 ns, 50 ns, and 100 ns) were extracted from the apo BLVRB trajectory, establishing that movement of part(s) of helix αE, Loop80, and Loop120 (as previously labeled [12]) are accomplished within the first 20 ns with no significant changes occurring during the final 80 ns of the simulation (Fig. 3). Loop40 undergoes considerable conformational changes in the first 20 ns, but returns to the position observed in the crystal structure (NADP+-BLVRB complex) at 50 ns leading to a decreased RMSD (Fig. 2). Loop40 has minimal conformational change during the last 50 ns and the observed change is presumably due to the high flexibility of this loop. Whereas movement of the N-terminus of the protein also contributes to the increase of RMSD from 30 ns to 70 ns, the most significant conformational changes are attributed to Loop80, Loop120, and the N-terminus of helix αE which primarily comprise the hydrophobic V/F binding pocket in the NADP+-BLVRB complex [12].

Fig. 3.

Movement of apo wild-type BLVRB in simulation. Simulations are determined from crystal structure (PDB entry 1HDO; white) to frame 20 ns, 50 ns, and 100 ns of the simulation. Red arrows represent residual conformational changes greater than 4.0 Å. The beginning of the arrow shows the location of residue in crystal structure, the end is the location of residue in MD simulation.

2.2 Serine111 is important for BLVRB thermodynamic stability and enzymatic activity

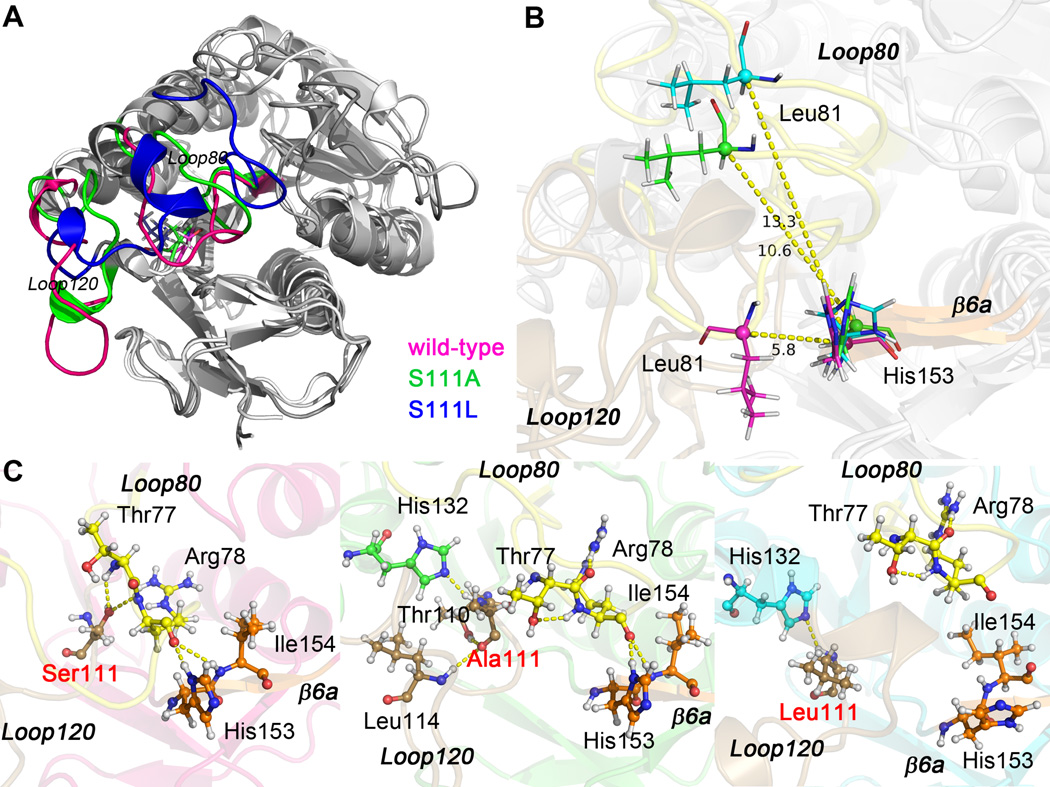

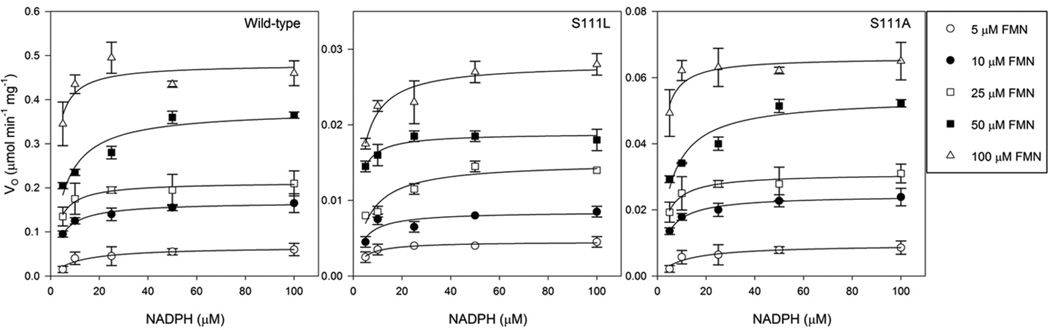

Serine111 is located in the core of the BLVRB active site [12] and is structurally homologous to the catalytic serine (Ser124 of the E. coli enzyme) of UDP-galactose 4-epimerase. [36] BLVRB Ala111 variant was specifically generated for subsequent comparison to the human Leu111 mutation.[27] Similar to apo BLVRB, the RMSD curves of apo variants have reached equilibrium at 100 ns: RMSD of Ser111Leu is 3.8 Å and Ser111Ala is 4.5 Å indicating greater conformational change of Ser111Ala (refer to Fig. 2). As shown in Fig. 4A, most of the conformational changes between apo BLVRB and either variant are located in Loop80 and Loop120. Importantly, the Ser111 sidechain conformation changes with the movement of both Loop80 and Loop120, readily evident by comparing the residual distance matrix among the three systems (Fig. 5, black boxes).

Fig. 4.

Superposed structures of frame 100 ns of apo wild-type, apo Ser111Ala, and apo Ser111Leu BLVRB. (A) Loop80 and Loop120 are colored for different systems (wild-type, pink; Ser111Ala, green; Ser111Leu, blue), residue 111 is shown in sticks. (B) Distance between Cα atom of Leu81 and Cα atom of His153. Loop80, Loop120, and β6a are labeled and colored in yellow, brown, and orange, respectively. (C) Hydrogen bonding network within Loop80 (yellow), Loop120 (brown), and β6a (orange) of apo wild-type, apo Ser111Ala, and apo Ser111Leu BLVRB. The mutation site is labeled in red, and hydrogen bonds are illustrated by yellow dashed lines.

Fig. 5.

Residual distance matrix of apo wild-type, apo Ser111Ala, and apo Ser111Leu BLVRB. Regions of largest conformational change are delineated by black boxes. Residual number of these regions are the same as that in Ref [12]: Loop10 (10–14), Loop40 (40–49), Loop55 (53–57), Loop80 (73–85), Loop120 (110–126), β6a (153–155).

The distance between Loop80 and β-strand 6a in apo BLVRB is the smallest among the three systems. For instance, in apo BLVRB, the distance between Cα of Leu81 and Cα of His153 is about 5.8 Å. However, this distance increases significantly to 10.6 and 13.3 in apo Ser111Ala and apo Ser111Leu systems, respectively (Fig. 4B). Comparison of structures between apo BLVRB and apo Ser111Ala shows Loop80 movement towards Loop40 in apo Ser111Ala; this shift is even greater for Ser111Leu. For both apo Ser111Leu and apo Ser111Ala, Loop120 moves towards Loop10, Loop40 and Loop55 (Fig. 5).

Changes in the hydrogen bonding network within BLVRB as a result of altering Ser111 were explored and are presented in Fig. 4C. In apo BLVRB, Loop80, Loop120, and β-strand 6a are linked together by several hydrogen bonds between the side chains of Ser111 and Thr77, Arg78; and between the side chains of Arg78 and His153, Ile154. When Ser111 is changed to Ala, the hydrogen bonds between Loop 80 and β-strand 6a remain intact, although the hydrogen bonding network between Loop80 and Loop120 is destroyed (vide infra). Changing Ser111 to Leu results in disruption of hydrogen bonds between Loop80 and β-strand 6a, and Loop80 is shifted away from Leu111.

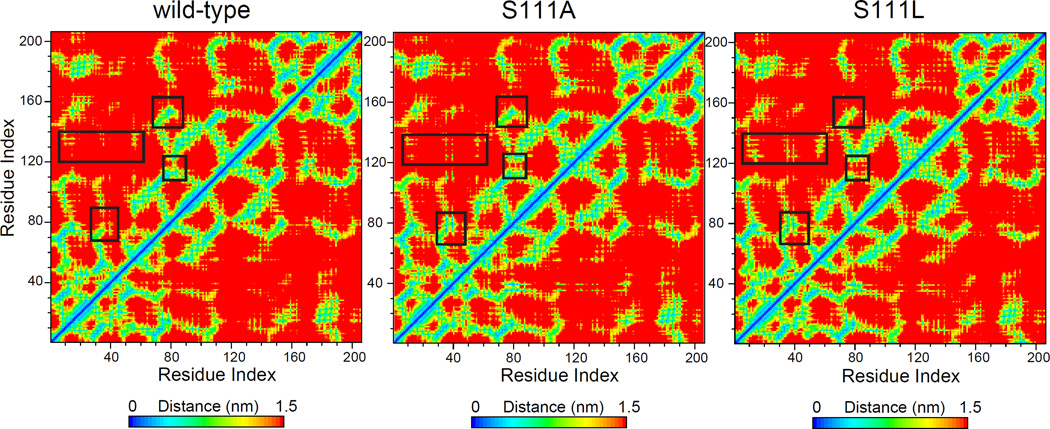

Aggregate results from our MD simulations suggested that changing Ser111 to either Ala or Leu could affect the stability of the folded structure of apo BLVRB, a structure-based model further explored using REMD (replica-exchange molecular dynamics) simulations based on the stable structure obtained from the MD simulations; in parallel, we validated these simulations using thermal shift assays. While the values of simulation temperatures are distinct from experimental temperatures (note that SBM uses reduced length, time, mass and energy units scaled to 1), relative values and trends can be applied for comparisons. Heat capacity curves were calculated using WHAM [37, 38] and comparative simulation and biochemical data are presented in Fig. 6. Apo BLVRB has the highest melting temperature (Tm), while Ser111Leu has the lowest Tm. The heat capacity curves of both Ser111Ala and Ser111Leu variants demonstrate a lower peak in front of the Tm peak, but this peak is flatter in the wild-type system. The lower peak may correspond to the temperature of a large conformational change; the height of this peak in Ser111Ala is larger than that in Ser111Leu, which is consistent with the RMSD trends (Fig. 2). Importantly, the overall temperature trends were comparable for the two methods, confirming that thermodynamic stability of the enzyme’s active site is maintained by the critical Ser111 hydrogen bond network.

Fig. 6.

Simulated and experimental thermodynamic stability. (A) Heat capacity curve of apo wild-type, apo Ser111Ala, and apo Ser111Leu systems was determined by replica-exchange molecular dynamics using 48 replicas ranging from 30 to 200 K, and the structure-based model of the stable structure [37, 38]; temperature is in reduced units. (B) Thermal stability of the different BLVRB variants as determined by shift assays from 20–70 °C.

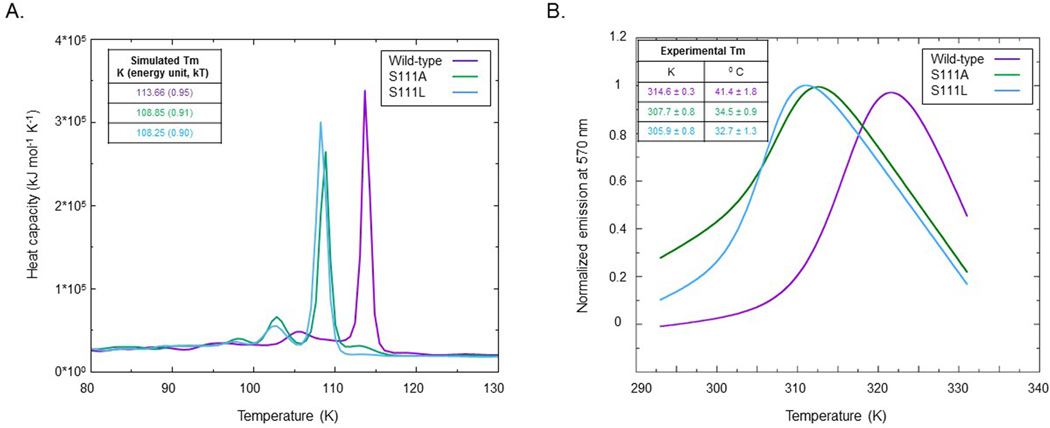

Finally, we specifically delineated serine-associated conformational effects from those on enzymatic activity by comparing the initial rate kinetics of wild-type, Ser111Leu and Ser111Ala; for these experiments we chose a reduced temperature (25 °C) demonstrated experimentally to maintain thermodynamic folding and enzymatic stability. As shown in Fig. 7 and Tab. 1, these results revealed comparable and across the three species, although both Ser111Ala and Ser111Leu demonstrated reduced Vmax and reduced kcat compared to wild-type, establishing an enzymatic role for Ser111 additive to that involved in maintaining its thermodynamic stability.

Fig. 7.

Initial rate kinetics of wild-type, Ser111Leu, and Ser111Ala BLVRB. Initial rates are plotted against the indicated concentrations of NADPH and delineated concentrations of FMN. Assays were performed in 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.5) at 25 °C, and all data points represent the mean±standard error of the mean of triplicate determinations. The solid lines are least-squares fits to a rectangular hyperbola. Data are shown for the (left) wild-type (0.5 µg), (middle) Ser111Leu (2 µg) and (right) Ser111Ala (1 µg).

Tab. 1.

Serine111 mutation characteristics

| Mutation | kcat (s−1) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type¶ | 102 ± 47 | 8.3 ± 2.1 | 0.171 ± 0.03 | 2.1 ± 104 | |||

| S111L¶ | 162 ± 21 | 5.8 ± 3.2 | 0.010 ± 0.001 | 1.7 ± 103 | |||

| S111A¶ | 137 ± 13 | 6.7 ± 3.7 | 0.025 ± 0.005 | 3.7 ± 103 |

All assays completed using identical reaction parameters at 25 °C. Errors represent standard deviation of the fit.

2.3 NAD(P)H-dependent conformational changes regulate formation of the hydrophobic substrate pocket

Putative effects of NADPH on the stabilization of the substrate/ligand binding pocket were then studied in more detail (Fig. 8). In the absence of NADP+, Loop80 (Val73 to Thr85) occludes the ligand binding pocket and prevents substrate binding, a conformation resulting in the “open” state of the enzyme. Upon NAD(P)H or NADP+ binding, Loop80, Loop120, and the N-terminus of helix αE are shifted to form the wall of the substrate binding pocket, a conformationally “closed” (or catalytically active) state (Fig. 8A–C). Internal hydrogen bonds with and without cofactor are shown in Fig. 8D. In the binary complex, β-strand 1, helix αA, Loop80, and β-strand 6a are stabilized by hydrogen bonds formed between NADP+ and the side chains of Thr12, Gln14, Thr15, Arg78, His153 and Ile154. In apo BLVRB, Loop80 forms direct hydrogen bonds with β-strand 1, helix αA, Loop120, and β-strand 6a (main hydrogen bonds are illustrated in the right panel of Fig. 8D), which contributes to pulling Loop80 from the original (PDB entry 1HE2) to the final position in apo BLVRB. This conformational change results in the formation of a hydrogen bond between the backbone H atom of Arg35 and the hydroxyl O atom of Thr12.

Fig. 8.

Conformational changes of ligand/substrate binding pocket with and without (apo) NADP+. (A) and (B) The superposed structures of frame 100 ns of apo wild-type BLVRB (pink), crystal structure PDB entry 1HDO (white), and PDB entry 1HE2 (yellow). The NADP+ and ligand biliverdin IXα (BLA) are shown in white and yellow sticks, respectively. Loop80 (from Val73 to Thr85) in apo simulation and crystal structures are compared to show the movement. The location of the ligand pocket in the ternary structure of BLVRB is illustrated as a blue circle. (C) The hydrophobicity surface of “closed” (left) and “open” (right) BLVRB conformational states. The “closed” conformation is represented with the crystal structure (PDB entry 1HE2); the “open” state is represented with frame 100 ns of apo simulation of BLVRB. NADP+ and BLA (pink sticks) are contained in the hydrophobic hole of the ternary complex structure. (D) Hydrogen bonding network in BLVRB ternary complex (PDB entry 1HE2, left) and apo BLVRB after MD simulation (right). Loop80 is colored in green and hydrogen bonds are represented by yellow dashed lines.

The BLVRB crystal structure shows that NADP+ is buried in the protein, with only the nicotinamide moiety available on the surface where it forms the floor of the hydrophobic pocket that binds verdins and flavins. [12] Electrostatic interactions between positively-charged side chains of amino acids in close proximity to the cofactor binding site and the 2’-phosphate of NADPH/NADP+ presumably account for BLVRB’s preference for NADPH. [39–46] Indeed, the 2’-phosphate of NADP+ is stabilized by salt bridges to the guanidinium side chains of Arg35 and Arg78 as well as polar contacts with the side chain hydroxyl of Thr12 [12] (left panel of Fig. 8D, these three residues are emphasized in bold). In addition to a charge interaction between Arg35 and the 2’-phosphate, this residue also stacks over the adenine ring. This stacking between the guanidinium side chain of arginine and the adenine ring of NADP+ is often observed in proteins containing an NADP+ dinucleotide-binding fold. [40, 47–51] The importance of Arg35 for discrimination between NADPH/NADP+ and NADH/NAD+ was confirmed by site-directed mutagenesis (Tab. 2). For these experiments, both NADPH and NADH concentrations were varied at a fixed concentration of FMN (150 µM) so that the kinetic constants are all apparent. Critical differences in the apparent Km for wild-type compared to R35A and R35S mutants were evident, however. With NADH as the variable substrate, the apparent Km approximates 110 µM for both R35A and R35S mutants (similar to wild-type), results which sharply contrast with those using NADPH as the cariable substrate. Compared to the native enzyme (Km 2.4 µM), the apparent Km for R35A mutant increases to 59 µM, approaching the value seen with the wild-type and NADH as substrate. There is a similar, but less dramatic trend for R35S mutant where the apparent Km increases to 29 µM. Thus, removal of this interaction in the Arg35Ala variant essentially removes the distinction between NADH and NADPH (Tab. 2). Mutation to alanine of two positively charged residues, Arg78Ala (that interacts with the 2’-phosphate of NADP+) and Arg39Ala (that is in close proximity) have little effect on cofactor preference (see left panel of Fig. 8D). These data suggest that the “clamping” role of Arg35 directs NADPH specificity and permits the subsequent “wrapping around” of Arg39 and Arg78. Indeed, the purified Arg35Ala variant does not contain bound NADP+ (the A280/A260 ratio increases from 1 in the wild type to 2.2 in the Arg35Ala and Arg35Ser variants). Finally, Ala111 forms hydrogen bonds with one residue (His132) of helix αE (see Fig. 4), although mutagenesis of His132Ala (or R174A, R124A) had no effect on substrate (), cofactor (), or kcat.

Tab. 2.

Mutation characteristics involving nucleotide and substrate/ligand pocket†

| Residues around the nucleotide (NADPH/NADH) pocket† | ||||||||

| Mutation | ||||||||

| Wild-type | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 0.220 ± 0.006 | 118 ± 24 | 0.087 ± 0.009 | ||||

| Arg35Ala | 59.0 ± 4 | 0.117 ± 0.004 | 108 ± 6 | 0.051 ± 0.001 | ||||

| Arg35Ser | 29.0 ± 5 | 0.090 ± 0.007 | 107 ± 20 | 0.055 ± 0.005 | ||||

| Arg78Ala | 4.7 ± 7 | 0.116 ± 0.003 | 150 ± 42 | 0.057 ± 0.009 | ||||

| Arg39Ala | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 0.150 ± 0.003 | 305 ± 90 | 0.111 ± 0.05 | ||||

| Trp116Ala | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 0.068 ± 0.001 | 186 ± 60 | 0.041 ± 0.009 | ||||

| Trp116Phe | 1.1 ± 0.07 | 0.140 ± 0.006 | 319 ± 125 | 0.049 ± 0.014 | ||||

| Residues around the substrate/ligand pocket | ||||||||

| Mutation | Vmax | kcat | ||||||

| Wild-type | 300 ± 144 | 0.643 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 0.237 ± 0.07 | ||||

| His132Ala | 222 ± 23 | 0.643 ± 0.04 | 4.9 ± 0.6 | 0.237 ± 0.07 | ||||

| Arg174Ala | ND | ND | 3 ± 0.24* | 0.4 ± 0.005** | ||||

| Arg124Ala | 95 ± 22 | 0.265 ± 0.03 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 0.097 ± 0.01 | ||||

The Km and appKm values are in µM, the Vmax and appVmax values are in µmol·min−1·mg−1, kcat value is in s−1 (reaction conditions 30 °C previously described).

For the Arg174Ala variant it was not possible to approach saturation for FMN so that no reliable estimates for the kM could be obtained (the νo versus [FMN] plots are essentially linear up to 150 µM).

The Km shown for the Arg174Ala mutant is an apparent Km at a fixed concentration of FMN (150 µM). ND: not determined.

3 Discussion

Metabolic consequences of stem cell fate are divergently associated with distinct patterns of redox activity and accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [52]; indeed, metabolically quiescent, non-cycling cells in the hypoxic bone marrow are typically ROSlow, while lineage commitment is associated with a metabolically-active bioenergetic phenotype manifest by ROShigh subsets. [53] We previously identified and characterized a loss-of-function BLVRB Ser111Leu mutation that promotes physiologically-relevant enhanced thrombopoiesis in humans. This mutation affects both flavin-and BV-regulated enzymatic activity, is associated with metabolic ROS mishandling and putative lineage fate decisions during a critical window of megakaryocyte/erythroid progenitor differentiation. [27] These observations provided the first evidence that heme-regulated redox activity maintains a metabolically-distinct hematopoietic function (and not a simple “catabolic” function), presumably as a tetrapyrrole-restricted redox coupler governing lineage (megakaryocyte) speciation. They also defined the first physiologically-relevant function of BLVRB unrelated to its secondary (or tertiary) role as a methemoglobin reductase in settings of erythroid stress. [22]

Complementary experimental and thermodynamic models as presented here have defined the critical role of Ser111 in the hydrogen-bonded network required for thermodynamics stability, this effect is additive to an effect regulating enzymatic activity. Both BLVRB and BLVRA enzymes have been identified as members of the SDR (short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase) protein family although they lack the signature Tyr(X)3Lys motif (where × is any amino acid) present in many in many family members. [11] The conserved tyrosine that serves as the catalytic base for most SDR enzymes has not been identified for either BLVRB or BLVRA. The closest structure neighbor to BLVRB is UDP-galactose 4-epimerase, [11, 12, 36] an enzyme that catalyzes the NAD+-dependent interconversion of UDP-galactose and UDP-glucose. Mechanistic studies of the E. coli enzyme reveal that a tyrosine (Tyr149 for E. coli) and a serine (Ser124) are important for catalysis with Tyr149 serving as the general base and Ser124 being involved in mediating proton transfer. [54] In addition to its role in catalysis, the hydroxyl group of Ser124 has been shown to be important for properly positioning the nicotinamide ring of NAD+ in the catalytically relevant conformation. Ser111 of BLVRB is structurally homologous to UDP-galactose 4-epimerase Ser124 and given that Ser111 is located near the nicotinamide ring of NADP+, [12] it appears likely that Ser111 functions in a cofactor arranging role similar to that described for Ser124, in addition to a structurally-stabilizing role within the enzymatic core.

Previous attempts to crystallize apo BLVRB have been unsuccessful as the cofactor appears to be required for maintaining structural stability under conditions amenable for crystallization. Interestingly, SBM and MD further established that NADP+ regulates the conformation of BLVRB by modulating the opening and closing of the hydrophobic substrate/ligand binding pocket, the only region of the protein where major conformational changes occur. Analysis of the crystallographic structure of NADP+ bound BLVRB revealed that Arg35 and Arg78 form salt bridges with the 2’-phosphate of NADP+, thereby stabilizing the cofactor, prompting mutagenesis studies which established that discrimination between NADPH and NADH is governed by Arg35. Binding of NADPH to BLVRB involves a two-step process including an initial “encounter complex” (KD 15.8 µM) that isomerizes in a nucleotide-induced mechanism to form a more stable “equilibrium complex” characterized by a KD of 0.55 µM.[19] Results from our SBM-MD simulations support this two-step process, such that the “open” state of BLVRB corresponding to the “encounter complex” resulting from the initial interaction of NAD(P)H with apo BLVRB. Conformational changes occurring as a result of NAD(P)H binding lead to the stable “equilibrium complex” in agreement with a sequential ordered mechanism. This NAD(P)H-dependent conformational change is expected be physiologically relevant during periods of altered cellular redox states in which the NAD(P)H:NAD(P) balance or absolute levels are altered. Indeed, cellular metabolic needs and bioenergetic states are not static, but often change during carcinogenic transformation, maintenance of pluripotency, or stochastic alterations leading to differentiation. [55] Furthermore, recent data using fluorescent probes capable of tracking the NAD(P)H/NAD(P) balance demonstrate clear heterogeneity in cellular subpopulations, suggesting distinct phenotypic outcomes regulated by alterations in NAD(P)H accumulation.[56] Thus, our data would suggest that bioenergetic alteration(s) associated with disordered NAD(P)H accumulation could serve to regulate substrate accessibility and resultant BLVRB redox activity.

BLVRB maintains a historically-enigmatic role in biology, variably characterized as a flavin reductase, methohemoglobin reductase, or (more recently) as a biliverdin reductase, and is certainly not as well studied as BLVRA. The name is additionally misleading because the enzyme catalyzes reduction of BV IXδ and BV IXγ isomers (in addition to BV IXβ), and binds promiscuously (and nonproductively) to other tetrapyrroles such as protohemin [21] or BV IXα [12, 19]. Unlike BV IXα, the relatively polar BV IXβ does not require glucuronidation for biliary excretion; furthermore, limited (BV IXβ, BV IXγ, BV IXδ) accumulation is evident in most tissues, suggesting that BV isomeric utilization may be more accidental than purposeful [22]; interestingly, this dichotomous expression of BLVRA/BLVRB is also evident in in Mycobacteria,[57, 58] suggesting BLVRB functions additive to those of heme metabolism and/or redox regulation. Finally, the recent development of phytochrome-optimized infrared probes retaining distinct biliverdin-dependent red-shifted fluorescence, [59] document that cells accumulate biliverdins. Although there are no data on BV quantification (and/or isomeric distribution), these observations appear somewhat paradoxical since both BLVRA and BLVRB are quite efficient in BV to BR catalytic activity (note for example that biliverdin accumulation in humans is essentially non-existent). One explanation is constant BV regeneration linked to a recycling BV/BR redox cycle for replenishment of the potent antioxidant BR IXα, [9] although it remains speculative (although likely) that BR IXβ (or BR IXγ, BR IXδ) are equally potent antioxidants. The thermodynamic simulations developed here provide computational models that can be applied to better understand the role of biliverdins, alternative substrates, or compounds retaining inhibitory or facilitatory BLVRB functions, collectively important for bioenergetic metabolism and ROS-neutralizing antioxidant functions.

4 Materials and Methods

4.1 Modeling the apo BLVRB structure

The three-dimensional crystal structure of BLVRB in complex with NADP+ (PDB 1HDO)[12] was used as the template for modeling apo BLVRB. Coordinates for the apo protein were generated by deleting the cofactor. This modeled apo protein then served as the template for building models for two variant forms of BLVRB (Ser111Ala and Ser111Leu) using PyMOL. [60] Missing sidechain and atoms have been added by grompp [61]. All the three systems (wild-type, Ser111Ala, and Ser111Leu) were solvated in implicit solvent, respectively. [62] The dielectric constant was set as 80 to mimic the aqueous environment of protein. Amber ff99SB force field was applied on them to produce the parameters. After a 30 ps energy minimization, 100 ns long-time dynamics simulation was performed on each system. All simulations were finished by Gromacs 4.5.5 [61], without cut-off of interactions (i.e. all interactions within the system were taken into consideration). The time step was set as 1 fs. The simulation temperature was 285 K.

4.2 Structure-based model

Upon reaching equilibrium in the 100 ns simulation, the apo structures of wild-type, Ser111Ala, and Ser111Leu BLVRB were using to generate the all-atom structure-based model (SBM) [63–65] by SMOG on-line toolkit. [63] These structures included all the heavy atoms of each amino acid residue. In this SBM, the native contact map was built by the Shadow Algorithm. [64] The potential energy function consists of both local (bond, angle, improper, and dihedral interactions) and non-local terms (attractive native contacts and repulsive non-native contacts). As a result, the potential energy form used in this study is given in the following equation:

| (1) |

where,

| (2) |

In Eq. 1, εr = 100ε, εθ = 20ε, εNC = 0.01ε, and σNC = 2.5 Å. The parameters, r0, θ0, χ0, ϕ0, and σij are given the values found in the native state. The dihedral angles shared the same two middle atoms are assigned in a group. Each dihedral is given the interaction strength of 1/ND, where ND is the number of dihedral angles in the group. Other parameters are set default according to the SMOG website. In the SBM, reduced units were used in the potentials. As a result, the value of simulation temperature is not the same as the “normal” temperature. However, the relative value and the trends of the temperature can be applied for comparison.

4.3 Calculation of the melting temperature of BLVRB

Replica-exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) [66] simulations were performed to obtain the thermodynamical properties of BLVRB systems. There are 48 replicas, ranging from 30 to 200 K on each SBM model. To ensure enough sampling, 10 ns simulation were performed in each replica. The Langevin equation was used for the simulation with constant friction coefficient γ = 1.0. The cut-off for non-local interactions was set as 3.0 nm. The time-step of REMD simulations was 2.0 fs, with all-bonds constrained by LINCS algorithm. [67] After simulation, the heat capacity Cν(T) of system can be calculated by using the weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM). [38, 68] The temperature with the highest heat capacity corresponds to the melting temperature (Tm) of the system.

4.4 Mutagenesis and biochemical assays

BLVRB enzymatic studies were completed using purified, recombinant enzymes (engineered by site-directed mutagenesis) that were expressed and purified as glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins as previously described with slight modifications. [69] Expression of wild-type BLVRB was induced with 0.1 mM IPTG and allowed to proceed for three hours, whereas expression of the Ser111Leu and Ser111Ala variants was carried out for one hour. Fusion proteins were eluted from glutathione-sepharose columns, and were cleaved overnight at 4 °C with 1 nM thrombin, resulting in >95% separation from the carrier. Cleaved proteins were re-passed through a glutathione-sepharose column, separated on a Sephacryl S-200 gel filtration column, and were >95% pure as established by SDS-PAGE and densitography; the presence of both Ser111Leu and Ser111Ala mutations were confirmed by automated DNA sequencing of the expression constructs, and tryptic digestion and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) mass spectroscopy of the purified recombinant proteins.

Initial rate kinetics with NADPH and with FMN were determined spectrophotometrically by monitoring the rate of oxidation of NADPH and NADP+ at 340 nm (ε340 =6.22 mM−1 · cm−1) using a Cary 60 UV/Vis spectrophotometer, essentially as previously described [20]. Assays were conducted at 30 °C (or 25 °C) in 100 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.2), 5–200 µM FMN and 5–100 µM NADPH. For assays containing Arg35Ala, Arg78Ala, Arg39Ala, Trp116Ala, and Trp116Phe, NADPH and NADH concentrations were varied at a fixed concentration of FMN (150 µM), and are reported as apparent Km (appKm) and apparent Vmax (appVmax). Initial rate data with FMN as the second substrate were fitted to a rectangular hyperbola and the kinetic constants and kcat were determined by the method of Florini and Vestling [70] using equation .

4.5 Thermal shift assays

Thermal melting temperatures were completed using Sypro Orange as a quantitative (fluorescent) parameter of protein-unfolding when exposed to hydrophobic surfaces. Wild-type BLVRB and Ser111Ala and Ser111Leu variants were heat denatured from 20–70 °C at 2 µM concentration in phosphate buffered saline pH 7.4 in a quartz cuvette with 10 mm path length. Fluorescence emission spectra were recorded in 2 °C intervals upon incubation for 1 min at each temperature. Fluorescence of Sypro Orange was recorded using a Horiba Jobin Yvon Fluoromax 4 spectrofluorometer (excitation/emission 470 nm/570 nm). All results are expressed as the mean ± SEM from triplicate determinations.

Acknowledgments

WTC and JW thank supports from National Natural Science Foundation of China (91430217), Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2016YFA0203200 and 2013YQ170585), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (21603217). WTC thanks support from China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2016M590268). JW thanks support from NSF-PHY-76066. WFB thanks supports from the NIH (HL091939), the New York State Stem Cell Foundation (C026716), and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. MAS thanks support from NIH (R35 GM119437-01). NMN thanks support from NIH (HL12945). We thank Drs. P. Pereira and S. Macedo-Ribeiro (Instituto de Biologia Molecular e Celular, University of Porto) for helpful discussions.

Abbreviations

- BV

biliverdin

- BR

bilirubin

- BLVRB

biliverdin reductase IXβ

- BLVRA

biliverdin reductase IXα

- HO

heme oxygenase

- SDR

short chain dehydrogenase/reductase

- SBM

structure-based models

- MD

molecular dynamics

- RMSD

root-mean-square deviation

- REMD

replica-exchange molecular dynamics

- V/F

verdin/flavin

- appKm

apparent Km

- appVmax

apparent Vmax

- Tm

melting temperature

References

- 1.Sugishima M, Migita CT, Zhang X, Yoshida T, Fukuyama K. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004;271:4517–4525. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakajima H, Takemura T, Nakajima O, Yamaoka K. J. Biol. Chem. 1963;238:3784–3796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tenhunen R, Marver HS, Schmid R. J. Biol. Chem. 1969;244:6388–6394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamaguchi T, Nakajima H. Eur. J. Biochem. 1995;233:467–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.467_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith LJ, Browne S, Mulholland AJ, Mantle TJ. Biochem. J. 2008;411:475–484. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakao A, Otterbein LE, Overhaus M, Sarady JK, Tsung A, Kimizuka K, Nalesnik MA, Kaizu T, Uchiyama T, Liu F, et al. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:595–606. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakao A, Neto JS, Kanno S, Stolz DB, Kimizuka K, Liu F, Bach FH, Billiar TR, Choi AM, Otterbein LE, et al. Am. J. Transplant. 2005;5:282–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamashita K, McDAID J, llinger R, Tsui T-Y, Berberat PO, Usheva A, Csizmadia E, Smith RN, Soares MP, Bach FH. FASEB J. 2004;18:765–767. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0839fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barañano DE, Rao M, Ferris CD, Snyder SH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:16093–16098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252626999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayer M. Clin. Chem. 2000;46:1723–1727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kavanagh K, Jörnvall H, Persson B, Oppermann U. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008;65:3895–3906. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8588-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pereira PJB, Macedo-Ribeiro S, Parraga A, Perez-Luque R, Cunningham O, Darcy K, Mantle TJ, Coll M. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2001;8:215–220. doi: 10.1038/84948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noguchi M, Yoshida T, Kikuchi G. J. Biochem. 1979;86:833–848. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a132615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kutty RK, Maines MD. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:3956–3962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schluchter WM, Glazer AN. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:13562–13569. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kikuchi A, Park S-Y, Miyatake H, Sun D, Sato M, Yoshida T, Shiro Y. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2001;8:221–225. doi: 10.1038/84955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shalloe F, Elliott G, Ennis O, Timothy J. Biochem. J. 1996;316:385–387. doi: 10.1042/bj3160385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mack CP, Hultquist DE, Shlafer M. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;212:35–40. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cunningham O, Dunne A, Sabido P, Lightner D, Mantle TJ. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:19009–19017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.25.19009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cunningham O, Timothy J, et al. Biochem. J. 2000;345:393–399. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu F, Mack CP, Quandt KS, Shlafer M, Massey V, Hultquist DE. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993;193:434–439. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDonagh AF. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2001;8:198–200. doi: 10.1038/84915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu G, Liu H, Doerksen RJ. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116:9580–9594. doi: 10.1021/jp301456j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitby FG, Phillips JD, Hill CP, McCoubrey W, Maines MD. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;319:1199–1210. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00383-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu F, Quandt KS, Hultquist DE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:2130–2134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamosh A, Scott AF, Amberger JS, Bocchini CA, McKusick VA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D514–D517. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu S, Li Z, Gnatenko DV, Zhang B, Zhao L, Malone LE, Markova N, Mantle TJ, Nesbitt NM, Bahou WF. Blood. 2016;128:699–709. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-02-696997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chu X, Wang Y, Gan L, Bai Y, Han W, Wang E, Wang J, et al. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012;8:e1002608. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, Gan L, Wang E, Wang J. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012;9:84–95. doi: 10.1021/ct300720s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Chu X, Suo Z, Wang E, Wang J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:13755–13764. doi: 10.1021/ja3045663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yao J, Wang J. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015;6:2022–2026. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b00524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitford PC, Ahmed A, Yu Y, Hennelly SP, Tama F, Spahn CM, Onuchic JN, Sanbonmatsu KY. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:18943–18948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108363108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cho SS, Levy Y, Wolynes PG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:434–439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810218105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ratje AH, Loerke J, Mikolajka A, Brünner M, Hildebrand PW, Starosta AL, Dönhöfer A, Connell SR, Fucini P, Mielke T, et al. Nature. 2010;468:713–716. doi: 10.1038/nature09547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noel JK, Sułkowska JI, Onuchic JN. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:15403–15408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009522107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thoden JB, Frey PA, Holden HM. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5137–5144. doi: 10.1021/bi9601114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenbergl JM. J. Comput. Chem. 1992;13:1011–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yeh I-C, Lee MS, Olson MA. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:15064–15073. doi: 10.1021/jp802469g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Z, Tsigelny I, Lee WR, Baker ME, Chang SH. FEBS Lett. 1994;356:81–85. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Didierjean C, Rahuel-Clermont S, Vitoux B, Dideberg O, Branlant G, Aubry A. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;268:739–759. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haeffner-Gormley L, Chen Z, Zalkin H, Colman RF. Biochemistry. 1992;31:7807–7814. doi: 10.1021/bi00149a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang S, Appleman JR, Tan X, Thompson PD, Blakley RL, Sheridan RP, Venkataraghavan R, Freisheim JH. Biochemistry. 1990;29:8063–8069. doi: 10.1021/bi00487a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levy HR, Vought VE, Yin X, Adams MJ. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1996;326:145–151. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sem DS, Kasper CB. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11539–11547. doi: 10.1021/bi00094a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sem DS, Kasper CB. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11548–11558. doi: 10.1021/bi00094a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yaoi T, Miyazaki K, Oshima T. FEBS Lett. 1994;355:171–172. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01191-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adams MJ, Ellis GH, Gover S, Naylor CE, Phillips C. Structure. 1994;2:651–668. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bailey S, Fairlamb AH, Hunter WN. Acta Cryst. D: Biol. Cryst. 1994;50:139–154. doi: 10.1107/S0907444993011898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scapin G, Blanchard JS, Sacchettini JC. Biochemistry. 1995;34:3502–3512. doi: 10.1021/bi00011a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thorn JM, Barton JD, Dixon NE, Ollis DL, Edwards KJ. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;249:785–799. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Waksman G, Krishna TS, Williams CH, Kuriyan J. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;236:800–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suda T, Takubo K, Semenza GL. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:298–310. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Owusu-Ansah E, Banerjee U. Nature. 2009;461:537–541. doi: 10.1038/nature08313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu Y, Thoden JB, Kim J, Berger E, Gulick AM, Ruzicka FJ, Holden HM, Frey PA. Biochemistry. 1997;36:10675–10684. doi: 10.1021/bi970430a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ying W. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2008;10:179–206. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blacker TS, Mann ZF, Gale JE, Ziegler M, Bain AJ, Szabadkai G, Duchen MR. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3936–3944. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ahmed FH, Carr PD, Lee BM, Afriat-Jurnou L, Mohamed AE, Hong N-S, Flanagan J, Taylor MC, Greening C, Jackson CJ. J. Mol. Biol. 2015;427:3554–3571. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ahmed FH, Mohamed AE, Carr PD, Lee BM, Condic-Jurkic K, O’Mara ML, Jackson CJ. Protein Sci. 2016;25:1692–1709. doi: 10.1002/pro.2975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shu X, Royant A, Lin MZ, Aguilera TA, Lev-Ram V, Steinbach PA, Tsien RY. Science. 2009;324:804–807. doi: 10.1126/science.1168683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.DeLano WL. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. San Carlos, CA: DeLano Scientific LLC; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Berendsen HJ, van der Spoel D, van Drunen R. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1995;91:43–56. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qiu D, Shenkin PS, Hollinger FP, Still WC. J. Phys. Chem. A. 1997;101:3005–3014. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Noel JK, Whitford PC, Sanbonmatsu KY, Onuchic JN. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W657–W661. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Noel JK, Whitford PC, Onuchic JN. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116:8692–8702. doi: 10.1021/jp300852d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Whitford PC, Noel JK, Gosavi S, Schug A, Sanbonmatsu KY, Onuchic JN. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Bioinf. 2009;75:430–441. doi: 10.1002/prot.22253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sugita Y, Okamoto Y. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1999;314:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hess B, Bekker H, Berendsen HJ, Fraaije JG, et al. J. Comput. Chem. 1997;18:1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kumar S, Rosenberg JM, Bouzida D, Swendsen RH, Kollman PA. J. Comput. Chem. 1992;13:1011–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cunningham O, Mantle TJ. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1997;25:S613. doi: 10.1042/bst025s613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Florini JR, Vestling CS. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1957;25:575–578. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(57)90529-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]