Abstract

Multiple lines of inquiry, including experimental animal models, have recently converged to suggest that executive functioning (EF) may be one mechanism by which parenting behavior is transmitted across generations. In the current investigation, we empirically test this notion by examining relations between maternal EF and parenting behaviors during mother-infant interactions, and by examining the role of maternal EF in the intergenerational transmission of parenting behavior. Mother-infant dyads (N=150) in a longitudinal study participated. Mothers were administered measures of EF (working memory and inhibition), reported on the parenting they received from their parents (i.e., the infants’ maternal grandparents), and were observed interacting with their 8-month-old infants. SEM findings indicated that the negative parenting mothers received from their own parents was significantly related to poorer maternal EF, and that poorer maternal EF was significantly related to subsequent engagement in more negative parenting practices with their own infant. A significant indirect effect, through maternal EF, was observed between maternal report of her experiences of negative parenting received while growing up and her own use of negative parenting practices. Our findings make two contributions. First, we add to existing work that has primarily considered relations between parent EF and parenting behavior while interacting with older children by showing that maternal EF affects children, via maternal parenting behavior, beginning very early in life. Second, we provide key evidence of the role of EF in the intergenerational transmission of parenting. Additional implications of these findings, as well as important future directions, are discussed.

Keywords: Executive Functioning, Intergenerational Transmission of Parenting, Longitudinal, Self-Regulation, Parent-Child Interactions

Building upon initial empirical studies (e.g., Bridgett et al., 2011; Deater-Deckard, Sewell, Petrill & Thompson, 2010) that demonstrated relations between maternal executive functioning (EF) and similar processes (e.g., effortful control) and aspects of caregiving behavior, recent reviews have highlighted the growing body of work showing that parent self-regulatory competencies have a potent influence upon the quality of parent-child interactions. In their review, focused on emotion regulation, Rutherford, Wallace, Laurent and Mayes (2015) concluded that emotion regulation is critical for aiding parents in responding adequately to child behavior, and for providing support for children’s emerging emotion regulatory capacities. Taking a broader perspective, Crandall, Deater-Deckard and Riley (2015) reviewed studies of relations between maternal cognitive and emotional control and parenting. These investigators also concluded that self-regulatory competencies play a key role in the provision of adequate child rearing.

Extending initial reviews, Bridgett, Burt, Edwards and Deater-Deckard (2015) reviewed literature that considered mechanisms, including studies linking aspects of parent self-regulation (e.g., EF) to parenting behavior, involved in the intergenerational transmission (IGT) of self-regulatory processes. Bridgett et al. reached a conclusion similar to that of other scholars – namely, that parent self-regulation affects the parenting that offspring experience – and added that parent self-regulatory competencies play important roles in shaping multiple aspects of the home environments children experience, which act as mechanisms in the IGT of self-regulation. One of the implications stemming from the model proposed by Bridgett et al. was that aspects of parent self-regulation, such as EF, may act as mechanisms in the IGT of family processes, and parenting behavior specifically. However, studies have not directly tested such a proposition. In addition, examination of the studies covered by the three existing reviews reveals that fewer investigations have considered the influence of parent EF on the parenting behavior experienced by children during infancy, a notable period when young children are reliant upon adequate caregiving to assist in their own regulation of affect and to promote adequate development of their nascent self-regulatory competencies (Kopp, 1982). The current investigation sought advance existing work and address gaps in knowledge by 1) examining relations between maternal EF and behavior during interactions with infants, and 2) examining the notion that EF may be a mechanism in the IGT of caregiver behavior.

Relations between Caregiving Behavior and Offspring EF

In order for EF to be a mechanism facilitating the IGT of parenting three conditions must be established. First, parenting behavior needs to influence offspring EF. Second, offspring EF should influence the parenting behavior in which they engage at the time they begin having children of their own. Third, parenting experienced by one generation (i.e., in the current study, parenting received by mothers of infants [i.e., from infants maternal grandparents]) needs to be linked to the parenting received by a subsequent generation (i.e., in the current study, parenting experienced by infants from their mothers) through EF (i.e., in the current study, maternal EF) via indirect relations. In regards to the first requirement, Kopp (1982) was among the first to recognize the role of caregiver behavior for facilitating (or hindering) the emergence and subsequent development of children’s self-regulation. Subsequently, Eisenberg and colleagues (Eisenberg et al., 1998) noted the role of parenting behavior for supporting children’s emotion-related regulation. Consistent with earlier models, recent conceptual models have emphasized the importance of caregiver behavior for supporting children’s emotion regulation (Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers, & Robinson, 2007) and behavioral and emotional regulation, including EF, more broadly (Bridgett et al., 2015).

Supporting, and informing, conceptual frameworks that have emphasized the influence of caregiver behavior on children’s regulation-related competencies, studies have consistently reported findings wherein parent behavior was related to children’s EF and to regulation-related constructs overlapping with EF, such as effortful control (see Bridgett et al., 2013, Eisenberg & Zhou, 2016, for discussion). In regards to effortful control, Spinrad et al. (2007) found that supportive parenting was associated with better toddler effortful control. Likewise, Kochanska and Knaack (2003) reported associations between higher maternal power assertion (a form of negative control of children) and lower children’s effortful control (also see Bridgett et al., 2011; Lengua, Honorado & Bush, 2007).

Like studies of relations between parenting and children’s effortful control, empirical works have noted relations between parenting and children’s EF. Bernier, Carlson and Whipple (2010) reported relations between the parenting behavior children experienced between 12 and 15 months of age, and aspects of EF when children were 18 and 26 months of age. Similarly, Blair and colleagues (Blair, Raver, Berry & Family Life Project Investigators, 2014) reported findings wherein adaptive maternal parenting was concurrently and longitudinally positively associated with a composite measure of children’s EF assessed when children were 3 and 5 years of age, and with increases in children’s EF between 3 and 5 years of age. Like maternal parenting, adaptive paternal parenting also appears to contribute to the emergence of children’s EF (Towe-Goodman et al., 2014). The studies highlighted here (also see Kraybill & Bell, 2013; Meuwissen & Carlson, 2015), provide compelling evidence that caregiving behavior is a potent influence on children’s EF.

Although longitudinal correlational studies in humans provide evidence of the effect of variations in caregiver behavior on offspring EF, such studies only go so far in establishing evidence of causal processes. However, the combination of animal models and human intervention research provide more direct evidence of such relations. Experimental designs using rodents, employing cross-fostering or artificial rearing methods, have obtained evidence that variations in caregiving behavior have causal effects on offspring self-regulatory competencies, such as EF (e.g., Lovic & Fleming, 2004; Lovic et al., 2011). Intervention studies in humans also have documented changes in children’s EF and other regulation-related processes following interventions targeting parenting practices. For example, Chang, Shaw, Dishion, Gardner and Wilson (2014) reported that children whose parents received a parenting intervention (compared to those that did not) exhibited improvements in inhibition and self-control (also see Chang, Shaw, Dishion, Gardner, & Wilson, 2015; Elizur, Somech, & Vinokur, 2015).

Across studies employing various methodologies, the existing body of evidence makes clear that parenting behavior has a potent influence on offspring EF (and other aspects of self-regulation), which appears to be due to the effects of parenting on neural and physiological processes underlying children’s EF (Belsky & de Haan, 2011; Bridgett et al., 2015). In light of human intervention studies and experimental animal models, which complement and extend longitudinal correlational studies in humans, we tentatively conclude that parenting behavior is one causal influence on offspring EF. This conclusion (and the literature upon which it is based) establishes a key piece of evidence in support of EF being a mechanism in the IGT of parenting behavior, and expectations for an association between parental caregiving behavior and offspring EF in the current investigation.

Associations between EF and Parenting Behavior

As noted in our opening, research has begun establishing a consistent link between aspects of parental self-regulation, like EF, and parenting behaviors. Such studies make clear that effective EF, and other self-regulatory competencies, are important for facilitating parent sensitivity, regulation of emotion in the face of challenging child behaviors, and regulation of decision making and parental behavior (e.g., limiting reactive negativity, promoting scaffolding and hindering intrusiveness) that facilitates, rather than hinders, children’s development, health and well-bring (Bridgett et al., 2015; Deater-Deckard, 2014). In one of the first studies to examine this question, Deater-Deckard, Sewell, Petrill, and Thompson (2010) found that mothers with poorer working memory were more likely to react negatively to challenging child behavior than mothers with better working memory. More broadly, mothers with poor EF have been found to respond to child conduct problems with harsh parenting more often than mothers with better EF (Deater-Deckard, Wang, Chen, & Bell, 2012). Finally, Cuevas and colleagues (2014) reported that better maternal EF was related to fewer negative parenting behaviors over time.

Whereas most work has considered older children, relatively fewer studies have considered caregiver EF in relation to parenting behavior experienced by infants. In one of the first studies to do so, Gonzalez, Jenkins, Steiner, and Fleming (2012) reported significant associations between poorer cognitive flexibility and spatial working memory and less maternal sensitivity during mother-infant interactions. Subsequently, in a study of teen and adult mothers that employed the same EF and maternal sensitivity coding procedures as Gonzalez et al., poorer performance during the cognitive flexibility task, but not the spatial working memory task, was related to less maternal sensitivity during mother-infant interactions (Chico, Gonzalez, Ali, Steiner, & Fleming, 2014).

Bolstering work that has directly considered EF, investigations examining relations between other aspects of self-regulation (e.g., effortful control, emotion regulation) and parenting has obtained similar findings. Studies have reported negative relations between better maternal effortful control and less maternal negative parenting (e.g., Bridgett, Laake, Gartstein, & Dorn, 2013), and positive relations between maternal effortful control and positive parenting (e.g. Davenport, Yap, Simmons, Sheeber, & Allen, 2011), similar to relations identified between EF and parenting. Likewise, parent emotion regulation has been related to caregiver behaviors (Kim, Pears, Capaldi, & Owen, 2009; Lorber, 2012).

Finally, animal models have started to provide important experimental evidence of the role of EF in the provision of parental behavior. In rodents, lesions to neural areas underlying EF have resulted in adverse effects on maternal behavior (Afonso, Sison, Lovic, & Fleming, 2007). Similarly, Lovic and Fleming (2004) reported that poorer attention shifting, induced via artificial rearing, was related to less maternal sensitivity. Findings within the experimental animal literature, alongside evidence from correlational studies in humans, led Bridgett et al. (2015) to conclude that there is mounting evidence of a causal influence of parent EF on variations in caregiving behavior. Thus, research on relations between self-regulation, including EF, and parenting points to a robust association, providing a basis for hypotheses that maternal EF will be related to parenting, and act as a mechanism of the IGT of parenting, in the current investigation.

Intergenerational Transmission of Parenting

The IGT of parenting has been of longstanding interest in the field, and has been the subject of considerable investigation, including a relatively recent special section appearing in Developmental Psychology (Belsky, Conger, & Capaldi, 2009). In short, studies have consistently noted relations between parental behaviors and attitudes across generations. For example, adolescents who reported being spanked by their mothers were found to be more approving of physical discipline techniques (Deater-Deckard, Lansford, Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 2003). Similarly, Kovan, Chung, and Sroufe (2009) observed parenting behavior in two generations, at the same point in development, when children were 24 months of age, finding a strong cross-generational association (also see Belsky, Jaffee, Sligo, Woodward, & Silva, 2005 for another example reporting cross-generational associations). Consistent with findings in human samples, studies employing experimental primate models also have found evidence of the IGT of parenting behavior. Maestripieri (2005), who employed cross-fostering methodology, reported that none of the non-abused infant Rhesus monkeys who were raised by either biological or foster mothers engaged in abusive parenting behavior, whereas over 50% of those that were abused by either their biological or foster mother engaged in abusive caregiving behavior toward their own infants.

Alongside interest in the IGT of parenting, there is growing interest in understanding mechanisms involved in the IGT of caregiver behavior. Existing work in this area has pointed to a number of potential mechanisms, including social competence, aggression and achievement (e.g., Neppl, Conger, Scaramella, & Ontai, 2009; Shaffer, Burt, Obradovic, Herbers, & Masten, 2009). For example, Neppl et al. examined externalizing difficulties and educational attainment as mediators of the IGT of parenting behavior. Externalizing behavior in the second generation mediated the relation between first and second generation harsh parenting, while academic attainment mediated the relation between first and second generation positive parenting. In regards to social competence, Shaffer et al. (2009) reported that social competence acted as a mechanism in the IGT of parenting.

In the closing of the special section on the IGT of parenting, Conger et al. (2009) recognized the evidence for existing mechanisms, while pointing to the possibility of other mechanisms, such as cognitive processes (e.g., EF) that had not yet been considered. Similarly, in a more recent review, Lomanowska, Boivin, Hertzman and Fleming (2015) pointed to the effects of early adversity, including the experience of chronic negative or abusive caregiving behavior as contributing to alterations in children’s neurobiology that underlie EF, and subsequently, the parenting experienced by youth in the next generation. However, despite calls for studies considering additional mechanisms of the IGT of parenting, such as EF, to date, studies have not yet considered such processes.

The Current Study

Multiple lines of evidence have converged to suggest that EF may be a mechanism in the IGT of parenting behavior; however, existing studies have not yet considered such a possibility. In the current study, we address this gap in the literature by examining EF as a mechanism in the IGT of negative parenting. We expected maternal report of negative parenting received from her parents over the first 16 years of life would be related to negative caregiving behaviors in which mothers engaged during mother-infant interactions. We also anticipated that mother’s report of parenting that was received over the course of her first 16 years of life would be related to her EF. Next, we anticipated maternal EF would be related to parenting behaviors observed during mother-infant interactions. Finally, we expected mediation, via an indirect effect, such that the parenting experienced by mothers would be related to their own caregiving behavior during mother-infant interactions through maternal EF.

Method

Participants & Procedure

Participants

Mothers and their infants (N = 150) were recruited from a rural setting through a local OB-GYN office and flyers posted throughout the community. During the course of the study, one infant developed a rare neurological condition, and data obtained from this family was excluded, resulting in a sample of 149 dyads. To be eligible, mothers had to be at least 17 years old and had to have a full term pregnancy with no significant prenatal or birth complications. Additionally, infants had to have no maternal reported developmental concerns at the time of enrollment into the study.

The mean age of mothers was 27.82 years (SD = 6.32), with 8.5% of mothers (n = 10) between 17 and 19 years of age (i.e., teenage mothers). For a sample obtained in a rural setting, participants were fairly diverse. While most mothers identified as Caucasian (70.9%), 12.0 % identified as African American, 12.0% identified as Hispanic/Latina, 1.7% identified as Native American, and 3.4% identified as “other”. On average, mothers had completed 14.64 years of education (SD = 2.77, range = 9–20); however, 11.2% of mothers had completed less than 12 years (high school) of education. The mean family income-to-needs ratio was 2.26 (SD = 1.74). Further, 23.6% of mothers reported a total annual income that was at or below the poverty threshold (i.e., income-to-needs ratio of less than or equal to one), while 57.3% of mothers were economically stressed, which was defined as an income-to-needs ratio of less than two. Among infants, 54.5% were female, while 45.5% were male.

Procedure

Shortly before infants reached four months of age, mothers were mailed packets containing the consent form and questionnaires. At four months postpartum mothers attended a laboratory visit where they completed additional questionnaires, measures of EF and a semi-structured clinical interview. Approximately six months postpartum mothers were mailed a second packet of questionnaires that included a measure of maternal childhood exposure to negative parenting. Because the initial visit involved a significant amount of time, the decision was made to have mothers complete this measure several months later to minimize the burden of the initial session. However, this does not disrupt the temporal order of constructs because the measure asked mothers to recall the parenting they had received during their first 16 years of life, a point prior to the completion of measures of EF. Finally, at eight months postpartum mothers and their infants visited the laboratory and participated in an unstructured free play task. Mothers were compensated for completion of each time point in the study.

Measures

Past parenting mothers received

To assess the parenting that mothers experienced while growing up, they completed the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI; Parker, Tupling, & Brown, 1979) (see Table 1 for means and standard deviations), a self-report measure of parenting received from mothers and fathers during the first 16 years of life. The PBI was selected because it has demonstrated reliability and validity, including convergence of reports among siblings and relations with observations of parenting behavior (e.g., Holmbeck et al., 2002; Parker et al., 1979; Parker, 1983). Four scales are derived from the PBI: care/warmth received from mothers (12 items; α = .94) and fathers (12 items; α = .94), and overprotection/control received from mothers (13 items; α = .88) and fathers (13 items; α = .87). Care/warmth subscales were reverse scored to reflect experiences of more negative parenting practices. Reverse scored father care/warmth was significantly related to father overprotection/control, r = .31, p = .001. Similarly, reverse scored mother care/warmth was significantly related to mother overprotection/control, r = .40, p < .001. Composites of negative parenting received from mothers (mean of mother low care/warmth and overprotection/control) and fathers (mean of father low care/warmth and overprotection/control) were formed and employed as indicators of a latent variable, maternal experience of negative parenting, used to test hypotheses.

Table 1.

Variable Means and Standard Deviations

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Cumulative Risk | 0.86 | 0.90 |

| Infant Negative Emotionality | 8.98 | 2.07 |

| Mother Negative Parenting | 0.00 | 0.84 |

| Father Negative Parenting | 0.00 | 0.81 |

| Working Memory Composite | −0.001 | 0.78 |

| Inhibition Composite | 0.00 | 0.81 |

| NA Parenting at 8 Months | 1.79 | 0.54 |

| Intrusive/Insen. Parenting at 8 Months | 1.68 | 0.61 |

Note: Descriptive statistics reflect untransformed means/standard deviations for cumulative risk, infant negative emotionality, NA Parenting and Intrusive/Insen. Parenting. For other variables, means are 0 because these reflect composite variables formed on the basis of standardized values.

Maternal executive functioning

Maternal Inhibition

To assess inhibition, mothers completed the Color-Word Interference test from the Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS; Delis et al., 2001). Three indices of inhibition were obtained from this measure: inhibition time, inhibition switching time, and total errors committed during the inhibition and inhibition switching trials. Longer completion times and more errors are indicative of poorer inhibition. After confirming significant inter-relations among indices, which ranged from r = .42, p < .001 to r = .53, p < .001 (M correlation = .48), a single inhibition composite (α = .64) was formed by standardizing and then averaging the three indices (i.e., inhibition time, inhibition switching time, and total errors). Higher composite scores, used as one observed indicator in a latent variable of poor maternal EF, are indicative of poorer maternal inhibition.

Maternal Working Memory

Mothers completed two measures of working memory. The letter-number sequencing test of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – 4th Edition (Wechsler, 2008) was administered, during which participants repeated increasingly longer series of numbers and letters. While doing so, participants first repeated the numbers in order from lowest to highest, and then the letters in alphabetical order. Sequences were administered in blocks of three, resulting in possible scores of 0 to 3 per block. Two indices from this measure, raw score and length of the longest correct sequence, were used in the working memory composite.

Mothers also completed the verbal fluency test from the D-KEFS (Delis et al., 2001), which can be used to assess working memory (see Unsworth, Spillers, & Brewer, 2011 for discussion of the role of working memory in performance during verbal fluency tasks). Three indices from this test were used in the working memory composite: letter fluency correct, category fluency correct, and category switching accuracy. During the letter fluency condition, participants said as many words as they could that start with “F”, “A”, and “S” in separate 60 second trials. During the category fluency condition, participants were asked to say as many animals and boys names as possible in separate trials of 60 seconds. Finally, during the category switching condition, participants switched between naming a fruit and a piece of furniture in a 60 second trial. Higher scores on these indices are consistent with better working memory.

Relations among working memory indices ranged from r = .35 to r = .81, all ps < .001 (M zero-order relation was .51). Based on these findings, indicators were reverse scored (higher scores = poorer working memory) to be consistent with higher scores from the inhibition task reflecting poorer inhibition, and then standardized. Subsequently, to derive the working memory composite (α = .70), the mean of the five standardized scores was obtained. Higher composite scores, the second observed variable used to form a latent variable of poor maternal EF, are consistent with poorer maternal working memory1.

Observed maternal parenting

Mothers and infants participated in a five minute unstructured free play task without toys when children were eight months of age. During the task, mothers were instructed to play with their infants as they normally would, though without any toys or stimuli. Interactions were video/audio recorded and later coded by trained observers using the Parent-Child Early Relational Assessment (PCERA; Clark, 1985). Coders rated maternal use of 13 parenting behaviors. On the basis of previous factor analytic work (Clark, 1999), five comprised negative affect/behavior (e.g. angry, hostile tone of voice, criticism of child) and eight comprised intrusiveness/insensitivity (e.g. rigid parenting style, inconsistent parenting). To determine inter-rater reliability, 20% of videos were coded a second time by an independent coder. Mean intra-class correlations were 0.74 for negative affect/behavior and 0.72 for intrusiveness/insensitivity, indicating good inter-rater reliability. Maternal intrusiveness/insensitivity and negative affect/behavior were used as indicators of a latent variable of maternal use of negative parenting behavior in the current investigation.

Covariates

Cumulative risk

In keeping with recommendations to account for risk that increases family stress, a cumulative risk index was derived for use in the current study. Families were assigned one point for the presence of each of the following risk factors: maternal education < high school, teen motherhood (age 17–19 years), income-to-needs ratio equal to or less than one (i.e. income at or below the poverty line), single motherhood, and current or past maternal depression (as measured by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders [SCID]; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002). The resulting index ranged from zero to five with higher scores indicating the presence of more risk factors.

Infant negative emotionality and sex

Consistent with conceptual models proposed by Crandall et al. (2015) and Bridgett et al. (2015), which suggest that child attributes may affect parent EF, and existing work showing child effects on parent behavior, maternal report of infant negative emotionality (NE) was obtained when children were 4 months of age and included as a covariate in the current study. NE was assessed using the Revised Infant Behavior Questionnaire (Gartstein & Rothbart, 2003) NE factor, which in this study consisted of the subscales sadness, distress to limitations/frustration and fear (α = .91). Finally, infant sex was also included as a covariate in light of evidence of differences in how caregivers may parent boys and girls (Hallers-Haalboom et al., 2014).

Analytic Approach

All variables were evaluated for normality. Any found to have significant skew (i.e., z = +/−2.00, based on the z-score obtained by dividing skew by the standard error of skew) were transformed either using a square-root or logarithmic transformation, depending upon the severity of the skew, as recommended by Tabachnick and Fidell (2007). Tests of hypotheses were conducted using SEM performed using EQS 6.3. In order to account for any remaining non-normality of variables, robust statistics were used where available. Model fit was examined using the robust Chi-Square Goodness of Fit Index, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). The standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) was also used to evaluate fit. An initial SEM was conducted to ascertain the relation between maternal childhood experience of negative parenting and her current use of negative parenting without maternal EF in the model. Subsequently, the final analysis was executed with maternal EF in the model using the effect decomposition feature of EQS to examine the indirect effect of interest.

Results

Missing Data

As is typical in longitudinal studies, some attrition occurred, resulting in missing data when children were 6 (12.8%) and 8 months (15.4%) of age. To assess for systematic patterns in missing data, the generalized least squares (GLS) test of combined covariance structure and means (Kim & Bentler, 2002) was examined in the final SEM model that included all primary variables, as well as covariates. The GLS test for the final SEM model was not significant, χ2 (283) = 317.31, p = .08, suggesting that there was not a systematic pattern to missing data. As such, full information maximum likelihood estimation was used to estimate missing values (Enders, 2010).

SEM Tests of Hypotheses

The initial SEM (See Table 2 for correlations), which only examined the direct relation between maternal report of the parenting she experienced from her mother and father while growing up, and observed parenting behavior with her infant was a good fit, χ2 (12) = 16.21, p = .18, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .049, and SRMR = .06. Importantly, negative parenting experienced by one generation was significantly related to negative parenting experienced by the subsequent generation, b* = 0.17, z = 2.42, p = .016. In regards to covariates in this initial model, infant sex was related to maternal report of the parenting she experienced while growing up, b* = 0.17, z = 2.23, p = .025, and family cumulative risk was related to observations of mother-infant interactions, b* = 0.31, z = 4.45, p < .001, and, at a trend level, to maternal report of the parenting she experienced while growing up, b* = 0.12, z = 1.68, p = .093. Finally, infant NE also was related to maternal report of the parenting she experienced while growing up, b* = 0.24, z = 3.48, p < .001. No other covariate relations reached trend-level or significance in this model. This model accounted for 14.2% of the variance (R2 = 0.142) in negative parenting behaviors observed during mother-infant interactions.

Table 2.

Zero-Order Associations between Variables

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Infant Sex (1 = boys) | - | |||||||

| 2. Cumulative Risk | 0.09 | - | ||||||

| 3. Infant NE | −0.15+ | 0.19* | - | |||||

| 4. Father Negative Parenting | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.22* | - | ||||

| 5. Mother Negative Parenting | 0.06 | 0.23** | 0.08 | 0.50** | - | |||

| 6. Poor Working Memory | 0.05 | 0.27** | 0.16+ | 0.30** | 0.13 | - | ||

| 7. Poor Inhibition | −0.05 | 0.31** | 0.09 | 0.19* | 0.20* | 0.52** | - | |

| 8. Neg. Affect/Behavior | 0.13 | 0.32** | −0.01 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.26** | 0.20* | - |

| 9. Intrusive/Insensitive | −0.03 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.19* | 0.24** | 0.26** | 0.58** |

NOTES: Missing values were not estimated for zero-order associations. “Mother” and “Father” refer to the infants’ maternal grandparents. Working memory and inhibition refer to the infants’ mothers EF, and Neg. Affect/Behavior and Intrusive/Insensitive are the two aspects of the infants’ mothers negative parenting behavior observed in this study.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p <.01

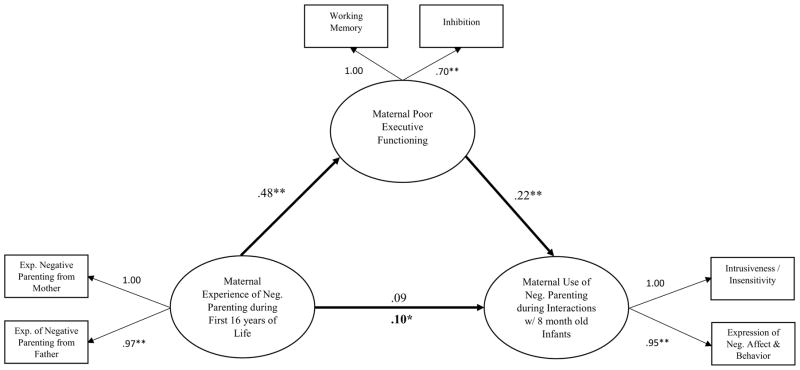

The final SEM model (Figure 1), which included covariates and maternal EF, examined maternal EF as a mechanism in the IGT of negative parenting, also was a good fit, χ2 (18) = 16.07, p = .59, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, and SRMR = .036. Variables accounted for approximately 20% of the variance in negative parenting behaviors observed during mother-infant interactions (R2 = 0.196). The negative parenting mothers reported receiving from her parents was significantly related to poorer maternal EF, b* = 0.48, z = 4.38, p < .001. Next, poorer maternal EF was related to negative parenting behaviors observed during mother-infant interactions, b* = 0.22, z = 2.66, p = .008. The direct relation between the negative parenting experienced by mothers, and the negative parenting observed during mother-infant interactions was not significant, b* = 0.09, z = 1.34, p = .18. However, the indirect effect2, through maternal EF was significant, b* = 0.10, z = 2.29, p = .022, indicating that maternal EF mediated the cross-generational parenting behavior relation.

Figure 1.

Final Model Depicting Findings for Main Hypotheses

* p < .05; ** p < .01

Error terms and covariates not included for clarity; findings regarding covariates are reported in the text. Indirect effect test of mediation is in bold below line. Model fit: χ2 (18) = 16.07, p = .59, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, SRMR = .036

Relations among covariates, and among covariates and primary constructs also were identified. Cumulative risk was associated with maternal EF, b* = 0.35, z = 3.48, p < .001, retrospective report of parenting received by mothers, b* = 0.19, z = 2.48, p = .013, observed mother-infant interactions, b* = 0.24, z = 3.15, p = .002, and with infant NE, b* = 0.20, z = 2.22, p = .026. Maternal report of the parenting they received growing up was related to infant NE, b* = 0.25, z = 3.47, p < .001. However, infant NE did not appear to influence maternal EF, b* = 0.09, z = 0.87, p = .38, or the quality of mother-infant interactions, b* = −0.07, z = −0.99, p = .32. Finally, infant sex was not related to cumulative risk, b* = 0.08, z = 1.09, p = .28, maternal EF, b* = −0.06, z = −0.61, p = .54, or observations of mother-infant interactions, b* = 0.07, z = 0.94, p = .35. There was a trend such that infant sex was related to infant negative emotionality, b* = −0.15, z = −1.88, p = .06 and to retrospective report of the parenting mothers received while growing up, b* = 0.14, z = 1.69, p = .09.

Discussion

In the current study, relations among maternal exposure to negative parenting during childhood, maternal EF, and maternal use of negative parenting behaviors during mother-infant interactions were examined. Findings were consistent with each of our hypotheses, which were formulated on the basis of existing theory, correlational evidence in separate areas of family science, human intervention studies, and experimental animal models. When examined without maternal EF in the model, negative parenting experienced by mothers, from both her mother and father (i.e., the infants’ maternal grandparents), was related to maternal use of more negative parenting practices during interactions with their infants. This finding, in terms of the direction and strength of the relation, was consistent with existing findings from works that have employed a variety of methods to examine the intergenerational continuity of parenting (e.g., Belsky et al., 2005; Conger et al., 2003; Deater-Deckard et al., 2003; Kovan et al., 2009).

Our other hypotheses also were supported. Consistent with a large body of evidence (e.g., Blair et al., 2014; Kraybill & Bell, 2013; Meuwissen & Carlson, 2015), negative parenting mothers reported receiving from their parents was related to poorer maternal EF. In turn, poorer maternal EF was related to more use of negative parenting during mother-infant interactions observed in a laboratory setting. This finding is consistent with a growing body of empirical evidence (Cuevas et al. 2014; Deater-Deckard et al., 2010) and recent conceptual models (Bridgett et al., 2015; Crandall et al., 2015; Rutherford et al., 2015) indicating that parent EF, and other aspects of self-regulation, has a strong, possibly causal, influence on parenting behavior. Finally, with maternal EF in the model, the relation between mother’s report of the parenting she received while growing up and the parenting behavior in which she engaged during mother-infant interactions was no longer significant. A statistical test of the indirect effect confirmed that maternal EF mediated the relation between parenting received in one generation and the parenting behavior experienced by the subsequent generation.

Our key finding that maternal EF mediated cross-generational parenting behavior associations has several implications. Importantly, this finding adds to the list of existing mechanisms, such as educational attainment and aggression (Neppl et al., 2009) implicated in the IGT of parenting. Along these lines, it is interesting to note that poor EF, and related constructs, have been implicated as risk factors for lower educational attainment (e.g., Côté, Gyurak, & Levenson, 2010; Zalewski et al., 2014), and increased aggression and externalizing difficulties (Schoemaker, Mulder, Dekovic, & Matthys, 2013). Given these findings, and because the emergence of EF (see Bridgett et al., 2015 for an overview) precedes the emergence of these outcomes, it may be that social competence, lower educational attainment and aggression have acted as proxies for poor EF, and potentially other self-regulatory difficulties, in existing studies seeking to identify mechanisms of the IGT of parenting. Having mentioned this possibility, it is important to note that we were unable to test such a proposition in the current investigation, and that this will be an essential avenue of inquiry for future studies to consider.

Next, because we considered interactions with infants, and late infancy is the period during which EF and other self-regulatory competencies begin emerging (Best & Miller, 2010; Rothbart, Sheese, & Posner, 2007), our findings that maternal EF mediated cross-generational parenting associations, and influenced the caregiving behavior infants received, suggests that the “seeds” of the IGT of parenting are “sown” early in development. Such a possibility mirrors a similar conclusion reached by Lomanowska et al. (2015), and highlights the importance of early screening and intervention (e.g., Chang et al., 2014; Sanders, 2012) for parents struggling to engage in behaviors that promote (rather than hinder) the development of children’s EF. Our findings also suggest that interventions for parent EF may have benefits for the parenting that children receive, which may disrupt the IGT of negative parenting behavior. Such interventions may be particularly potent when paired with interventions that promote the use of caregiving that is beneficial for children’s EF.

Finally, our finding that maternal EF mediated the cross-generational transmission of negative parenting has another interesting implication when considered in tandem with a recent model of processes involved in the IGT of self-regulation, including EF (see Bridgett et al., 2015). That is, because family processes, parenting behavior in particular, seem to be social mechanisms in the IGT of self-regulation, when considered alongside findings in the current investigation, the possibility of multiple processes (e.g., parent behavior, EF) involved in the near simultaneous IGT of one another becomes apparent. This is an important possibility that future studies will need to consider, ideally using multi-generational studies that employ multiple observations of parent behavior and direct assessments of parent and child EF.

In addition to providing preliminary evidence that EF acts as one mechanism in the IGT of negative parenting behavior, our study makes several additional contributions. In particular, our study adds to the growing literature (e.g., Chico et al., 2014; Gonzalez et al., 2012) showing that maternal EF, and other self-regulatory processes, influence the caregiving that is experienced by young children. Given the converging evidence, it is clear that maternal EF exerts a notable influence on parenting behavior experienced by infants during a key point in development when neural systems supporting EF and other self-regulatory processes begin coming “online” (Best & Miller, 2010; Rothbart et al., 2007) and behavioral manifestations of effective EF begin emerging (e.g., performance during the A not B task). Future work will need to examine early manifestations of infant and toddler self-regulation to determine if parent EF influences young children’s regulation through parenting.

Our findings also provide information regarding factors that may be related to or influence parent EF based on expectations from several recent theoretical models. Models proposed by Bridgett et al. (2015) and Crandall et al. (2015) place a role on the relations between parent EF and contextual stress, such as cumulative risk, included in the current investigation. Although we are unable to consider the direction of this relation, our findings provide support for the notion that parent EF is related to contextual stressors, such as those often included within cumulative risk indices. Future work is needed that seeks to identify whether the nature of such relations is directional or bi-directional. The models proposed by Bridgett et al. and Crandall et al. also suggest the possibility of child effects on parent EF. However, we did not find evidence that infant NE, a more likely infant attribute that could influence parent EF, was related to maternal EF. Nevertheless, given the nature of our design, we do not consider our study to be a “strong” test of the possibility of child effects on parent EF. For example, it may be that child effects on parent EF are not present in infancy, but emerge during later developmental periods, perhaps when parents encounter situations wherein children’s emotions and behavior are more difficult to manage. Thus, continued investigation of potential child effects on parent EF is warranted in future studies.

Limitations/Strengths

Although our study makes several contributions to the existing literature it is not without limitations. The chief limitation was our reliance on mother’s retrospective report of the parenting that was received while growing up. Use of such an approach raises concerns regarding maternal recall bias, or the possibility that later events biased such recollections. However, consideration of the strengths of our study suggests that such possibilities had minimal, if any effects on conclusions. First, relations, in terms of their direction and strength, between maternal reports of the parenting that was experienced while growing up and maternal EF and use of negative parenting practices were theoretically expected and consistent with a large empirical base that has collectively employed a range of methods for the assessment of key constructs, including observations of parenting across generations (e.g., Kovan et al., 2009) and experimental animal models (e.g., Maestripieri, 2005). In addition to theoretical/empirical consistency of our findings with prior work, our use of direct assessment of maternal EF and observations of mother-infant interactions, instead of maternal self-report, helped to guard against and minimize any effects of maternal recall or self-report biases. Last, because we used maternal report of infant NE, had there been systematic report bias, relations between infant NE and maternal EF and observations of parenting during mother-infant interactions might have mirrored relations between maternal reports of the parenting that was experienced while growing up and maternal EF and mother-infant interactions. Such similarity did not occur. In sum, these factors help to mitigate any adverse effects stemming from our use of maternal report of the parenting that she experienced growing up on our findings and conclusions.

Our use of maternal report of the parenting that was received from her parents, while a potential limitation in some regards, is a strength in others. Mothers reported on the parenting they received from both parents, allowing us to consider the collective effects of parenting on maternal EF and the parenting mothers used while interacting with infants. Use of maternal report also allowed us to conduct a study on cross-generational parenting behavior relations in a shorter time frame than would be possible had other methods been employed. Despite the potential strengths of using maternal report of the parenting that she received, and methodological features of our study that help to mitigate limitations stemming from such an approach, future studies will want to employ approaches (e.g., direct observation of parenting behaviors across multiple generations) to avoid potential limitations of retrospective self-report measures.

It also may be possible that poor maternal EF, particularly working memory, influenced recollection of parenting mothers received while growing up. However, such a possibility is inconsistent with the large body of work showing that parenting is related to subsequent EF and related self-regulatory processes (Blair et al., 2014; Towe-Goodman et al., 2014). Moreover, at the zero-order level, maternal report of parenting she experienced was related to both working memory and inhibition. These factors provide evidence against the possibility that poor maternal EF influenced how mothers recalled the parenting they experienced while growing up, though future work might consider assessing long-term memory in addition to EF to completely rule out such a possibility.

We only considered two aspects of maternal EF. However, EF has three core components: working memory, inhibition and cognitive flexibility (Miyake, Friedman, Emerson, Witzki, & Howerter, 2000). Though future studies will want to consider all aspects of EF in relation to parenting, prior studies (Chico et al., 2014; Gonzalez et al., 2012) examining relations between maternal EF and parenting behavior during mother-infant interactions used a combination of measures of spatial working memory and attention shifting, and reported findings similar to those we obtained. It also should be noted that we focused on the cross-generational transmission of negative parenting, not positive parenting. While we would anticipate similar findings had aspects of positive parenting been considered, particularly in light of existing work that has reported anticipated relations between aspects of positive parenting across generations (e.g., Neppl et al., 2009; Shaffer et al., 2009), future studies should examine parent EF as a mechanism by which positive parenting (e.g., warmth, sensitivity) may be transmitted across generations. The current study also focused on maternal experience with negative parenting while growing up, mother’s subsequent use of negative parenting during mother-infant interactions, and maternal EF. It will be vital for future studies to examine the interplay among these attributes and behaviors of fathers.

Next, we only considered how one mechanism contributes to the IGT of parenting behaviors. It will be important for future studies to consider multiple mechanisms, including EF, to ascertain the relative contribution and importance of each mechanism while accounting for the effects of other potential mechanisms. As one example, there may be other intermediary mechanisms involved in the intergenerational transmission of parenting, such as hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis functioning, which could influence EF or parenting behavior directly. Existing studies and conceptual works point to such a possibility. For example, negative parenting may result in children’s perturbed stress response over time, which may disrupt developing neural mechanisms underlying EF and other aspects self-regulation (Blair et al., 2011; Bridgett et al., 2015; Lomanowska et al., 2015; Gonzalez et al., 2012). Thus, models that consider multiple mechanisms (e.g., HPA axis function and EF), and serial mediation, in the intergenerational transmission of parenting behavior are needed. Finally, it is important to note that the design we employed is not genetically sensitive, rendering it impossible to completely rule out the possibility of genetic influences on our findings. Future studies should seek to extend our approach by employing genetically sensitive designs that are well-suited for teasing apart effects that might be attributable to shared genetic influence, and those that are not.

Conclusion

Our findings provided key preliminary evidence that maternal EF is one mechanism through which negative parenting behaviors are transmitted across generations. Furthermore, we also provided important findings regarding the role of maternal EF in the provision of the caregiving that infants experience. While continued work examining relations between caregiver self-regulatory processes, such as EF, and aspects of family dynamics, such as parenting behavior, continues to be needed, our findings provide important information for the field regarding why the study of the interplay between parent EF and family processes will continue to be of importance. Indeed, we believe that the study of parent EF and other self-regulatory processes has the potential to shed new light on the individual difference origins of complex family processes (for a review that includes, but also extends beyond parenting behaviors, see Bridgett et al., 2015), within and between generations, and is likely to yield new avenues of inquiry for basic family science and new targets for interventions.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by R21HD072574 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD). The content is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the NICHD or the National Institutes of Health.

We appreciate the contributions from the families that participated in this study, and the many individuals involved in this project who made it possible. In particular, we wanted to acknowledge the contributions of Katherine Oddi, Lauren Laake, Nicole Burt, Erin Edwards, Lauren Boddy, Melissa Bachmann, Mary Baggio, Elliott Ihm and Sarah Vadnais.

Footnotes

Because the verbal fluency category switching and the color-word inhibition switching indices may measure cognitive flexibility/attention shifting, we performed a Principal Components analysis of all individual EF indicators using Direct Oblimin, an oblique rotation procedure that is used when correlated factors may be present, to check the manner in which we combined EF indictors to form observed composites of working memory and inhibition. Results indicated the presence of two factors with Eigen values above 1, accounting for 63.49% of the variance. The Letter-Number Sequencing indices and Verbal Fluency indices loaded onto the first factor, and the Color-Word Interference Test indices loaded onto the second factor. A third factor, comprised of the two switching-related indices did not emerge. The two factors were related, r = .44. These findings support the approach we adopted in regards to forming composite indicators of EF for use in latent variable tests of hypotheses.

We obtained the bootstrap confidence interval of the indirect effect using options available in EQS 6.3. However, output reporting the standardized values of the confidence interval is not available. In addition, only the 90% confidence interval is provided. The unstandardized value for the indirect effect was 0.13, with a bootstrap 90% CI of 0.01 to 0.37.

Contributor Information

David J. Bridgett, Northern Illinois University

Meghan J. Kanya, Northern Illinois University

Helena J. V. Rutherford, Yale University

Linda C. Mayes, Yale University

References

- Afonso VM, Sison M, Lovic V, Fleming AS. Medial prefrontal cortex lesions in female rat affect sexual and maternal behavior and their sequential organization. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2007;121:515–526. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.3.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Conger R, Capaldi DM. The intergenerational transmission of parenting: Introduction to the special section. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1201–1204. doi: 10.1037/a0016245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, de Haan M. Annual research review: Parenting and children’s brain development: The end of the beginning. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52:409–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Jaffee S, Sligo J, Woodward L, Silva P. Intergenerational transmission of warm-sensitive-stimulating parenting: A prospective study of mothers and fathers of 3-year-olds. Child Development. 2005;76:384–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best JR, Miller PH. A developmental perspective on executive function. Child Development. 2010;81:1641–1660. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier A, Carlson SM, Whipple N. From external regulation to self-regulation: Early parenting precursors of young children’s executive functioning. Child Development. 2010;81:326–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, Granger DA, Willoughby M, Mills-Koonce R, Cox M, Greenberg MT, Kivlighan KT, Fortunato CK Family Life Project Investigators. Salivary cortisol mediates effects of poverty and parenting on executive functions in early childhood. Child Development. 2011;82:1970–1984. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01643.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, Raver CC, Berry DJ Family Life Project Investigators. Two approaches to estimating the effect of parenting on the development of executive function in early childhood. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50:554–565. doi: 10.1037/a0033647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridgett DJ, Burt NM, Edwards ES, Deater-Deckard K. Intergenerational transmission of self-regulation: A multidisciplinary review and integrated conceptual framework. Psychological Bulletin. 2015;141:602–654. doi: 10.1037/a0038662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridgett DJ, Gartstein MA, Putnam SP, Lance KO, Iddins E, Waits R, … Lee L. Emerging effortful control in toddlerhood: The role of infant orienting/regulation, maternal effortful control, and maternal time spent in caregiving activities. Infant Behavior and Development. 2011;34:189–199. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridgett DJ, Laake LM, Gartstein MA, Dorn D. Development of infant positive emotionality: The contribution of maternal characteristics and effects on subsequent parenting. Infant and Child Development. 2013;22:362–382. doi: 10.1002/icd.1785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bridgett DJ, Oddi KB, Laake LM, Murdock KW, Bachmann MN. Integrating and differentiating aspects of self-regulation: Effortful control, executive functioning, and links to negative affectivity. Emotion. 2013;13:47–63. doi: 10.1037/a0029536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Gardner F, Wilson MN. Direct and indirect effects of the family check-up on self-regulation from toddlerhood to early school-age. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42:1117–1128. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9859-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Gardner F, Wilson MN. Proactive parenting and children’s effortful control: Mediating role of language and indirect intervention effects. Social Development. 2015;24:206–223. doi: 10.1111/sode.12069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chico E, Gonzalez A, Ali N, Steiner M, Fleming AS. Executive function and mothering: Challenges faced by teenage mothers. Developmental Psychobiology. 2014;56:1027–1035. doi: 10.1002/dev.21185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall A, Deater-Deckard K, Riley AW. Maternal emotion and cognitive control capacities and parenting: A conceptual framework. Developmental Review. 2015;36:105–126. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R. Instrument and manual. Madison, WI: Department of Psychiatry, University of Wisconsin Medical School; 1985. The parent-child early relational assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Clark R. The parent-child early relational assessment: A factorial validity study. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1999;59:821–846. doi: 10.1177/00131649921970161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Belsky J, Capaldi DM. The intergenerational transmission of parenting: Closing comments for the special section. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1276–1283. doi: 10.1037/a0016911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté S, Gyurak A, Levenson RW. The ability to regulate emotion is associated with greater well-being, income, and socioeconomic status. Emotion. 2010;10:923–933. doi: 10.1037/a0021156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas K, Deater-Deckard K, Kim J, Watson A, Morasch K, Bell MA. What’s mom got to do with it? Contributions of maternal executive function and caregiving to the development of executive function across early childhood. Developmental Science. 2014;17:224–238. doi: 10.1111/desc.12073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport E, Yap MB, Simmons JG, Sheeber LB, Allen NB. Maternal and adolescent temperament as predictors of maternal affective behavior during mother–adolescent interactions. Journal of Adolescence. 2011;34:829–839. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K. Family matters: Intergenerational transmission and interpersonal processes of executive function and attentive behavior. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2014;23:230–236. doi: 10.1177/0963721414531597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Lansford JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. The development of attitudes about physical punishment: An 8-year longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:351–360. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Sewell MD, Petrill SA, Thompson LA. Maternal working memory and reactive negativity in parenting. Psychological science. 2010;21:75–79. doi: 10.1177/0956797609354073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Wang Z, Chen N, Bell MA. Socioeconomic risk moderates the link between household chaos and maternal executive function. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26:391–399. doi: 10.1037/a0028331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer J. Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9:241–273. doi: 10.1037/a0030977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Zhou Q. Conceptions of executive function and regulation: When and to what degree do they overlap? In: Griffin JA, McCardle P, Freund LS, editors. Executive function in preschool-age children: Integrating measurement, neurodevelopment, and translational research. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2016. pp. 115–136. [Google Scholar]

- Elizur Y, Somech LY, Vinokur AD. Effects of parent training on callous-unemotional traits, effortful control, and conduct problems: Mediation by parenting. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10802-016-0163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. User’s Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders—Research Version. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gartstein MA, Rothbart MK. Studying infant temperament via the Revised Infant Behavior Questionnaire. Infant Behavior & Development. 2003;26:64–86. doi: 10.1016/S0163-6383(02)00169-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez A, Jenkins JM, Steiner M, Fleming AS. Maternal early life experiences and parenting: The mediating role of cortisol and executive function. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51:673–682. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallers-Haalboom ET, Mesman J, Groeneveld MG, Endendijk, van Berkel SR, van der Pol LD, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. Mothers, fathers, sons and daughters: Parental sensitivity in families with two children. Journal of Family Psychology. 2014;28:138–147. doi: 10.1037/a0036004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN, Johnson SZ, Wills KE, McKernon W, Rose B, Erklin S, Kemper T. Observed and perceived parental overprotection in relation to psychosocial adjustment in preadolescents with a physical disability: The mediational role of behavioral autonomy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:96–110. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.96. doi:10:1037//0022-006X.70.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KH, Bentler PM. Tests of homogeneity of means and covariance matrices for multivariate incomplete data. Psychometrika. 2002;67:609–624. doi: 10.1007/BF02295134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Pears KC, Capaldi DM, Owen LD. Emotion dysregulation in the intergenerational transmission of romantic relationship conflict. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:585–595. doi: 10.1037/a0015935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Knaack A. Effortful control as a personality characteristic of young children: Antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Personality. 2003;71:1087–1112. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CB. Antecedents of self-regulation: A developmental perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18:199–214. [Google Scholar]

- Kovan NM, Chung AL, Sroufe LA. The intergenerational continuity of observed early parenting: A prospective, longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1205–1213. doi: 10.1037/a0016542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraybill JH, Bell MA. Infancy predictors of preschool and post-kindergarten executive function. Developmental Psychobiology. 2013;55:530–538. doi: 10.1002/dev.21057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ, Honorado E, Bush NR. Contextual risk and parenting as predictors of effortful control and social competence in preschool children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2007;28:40–55. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomanowska AM, Boivin M, Hertzman C, Fleming AS. Parenting begets parenting: A neurobiological perspective on early adversity and the transmission of parenting styles across generations. Neuroscience. 2015 doi: 10.1016/neuroscience.2015.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorber MF. The role of maternal emotion regulation in overreactive and lax discipline. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26:642–647. doi: 10.1037/a0029109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovic V, Fleming AS. Artificially-reared female rats show reduced prepulse inhibition and deficits in the attentional set shifting task – Reversal of effects with maternal-like licking stimulation. Behavioural Brain Research. 2004;148:209–219. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(03)00206-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovic V, Palombo DJ, Fleming AS. Impulsive rats are less maternal. Developmental Psychobiology. 2011;53:13–22. doi: 10.1002/dev.20481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestripieri D. Early experience affects the intergenerational transmission of infant abuse in rhesus monkeys. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:9726–9729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504122102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuwissen AS, Carlson SM. Fathers matter: The role of father parenting in preschoolers’ executive function development. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2015;140:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS, Robinson LR. The role of family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development. 2007;16:361–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology. 2000;41:49–100. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1999.0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neppl TK, Conger RD, Scaramella LV, Ontai LL. Intergenerational continuity in parenting behavior: Mediating pathways and child effects. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1241–1256. doi: 10.1037/a0014850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G, Tupling H, Brown LB. A parental bonding instrument. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1979;52:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Parker G. Parental overprotection: A risk factor in psychosocial development. Grune & Stratton; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Sheese BE, Posner MI. Executive attention and effortful control: Linking temperament, brain networks, and genes. Child Development Perspectives. 2007;1:2–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2007.00002.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford HJV, Wallace NS, Laurent HK, Mayes LC. Emotion regulation in parenthood. Developmental Review. 2015;36:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders MR. Development, evaluation, and multinational dissemination of the triple P-Positive Parenting Program. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2012;8:345–379. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-0325110143104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoemaker K, Mulder H, Dekovic M, Matthys W. Executive functions in preschool children with externalizing behavior problems: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41:457–471. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9684-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer A, Burt KB, Obradovic J, Herbers J, Masten AS. Intergenerational continuity in parenting quality: The mediating role of social competence. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1227–1240. doi: 10.1037/a0015361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinrad TL, Eisenberg N, Gaertner B, Popp T, Smith CL, Kupfer A, … Hofer C. Relations of maternal socialization and toddlers’ effortful control to children’s adjustment and social competence. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1170–1186. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.5.1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 5. New York: Pearson; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Towe-Goodman NR, Willoughby M, Blair C, Gustafsson HC, Mills-Koonce RW, Cox MJ The Family Life Project Key Investigators. Fathers’ sensitive parenting and the development of early executive functioning. Journal of Family Psychology. 2014;28:867–876. doi: 10.1037/a0038128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth N, Spillers GJ, Brewer GA. Variation in verbal fluency: A latent variable analysis of clustering, switching, and overall performance. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2011;64:447–466. doi: 10.1080/17470218.2010.505292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler adult intelligence scale. 4. San Antonio, TX: Pearson; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zalewksi M, Stepp SD, Scott LN, Whalen DJ, Beeney JF, Hipwell AE. Maternal borderline personality disorder symptoms and parenting of adolescent daughters. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2014;28:541–554. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2014_28_131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]