Abstract

Objectives To analyse the efficacy of acupuncture as a complementary therapy to the pharmacological treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee, with respect to pain relief, reduction of stiffness, and increased physical function during treatment; modifications in the consumption of diclofenac during treatment; and changes in the patient's quality of life.

Design Randomised, controlled, single blind trial, with blinded evaluation and statistical analysis of results.

Setting Pain management unit in a public primary care centre in southern Spain, over a period of two years.

Participants 97 outpatients presenting with osteoarthritis of the knee.

Interventions Patients were randomly separated into two groups, one receiving acupuncture plus diclofenac (n = 48) and the other placebo acupuncture plus diclofenac (n = 49).

Main outcome measures The clinical variables examined included intensity of pain as measured by a visual analogue scale; pain, stiffness, and physical function subscales of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) osteoarthritis index; dosage of diclofenac taken during treatment; and the profile of quality of life in the chronically ill (PQLC) instrument, evaluated before and after the treatment programme.

Results 88 patients completed the trial. In the intention to treat analysis, the WOMAC index presented a greater reduction in the intervention group than in the control group (mean difference 23.9, 95% confidence interval 15.0 to 32.8) The reduction was greater in the subscale of functional activity. The same result was observed in the pain visual analogue scale, with a reduction of 26.6 (18.5 to 34.8). The PQLC results indicate that acupuncture treatment produces significant changes in physical capability (P = 0.021) and psychological functioning (P = 0.046). Three patients reported bruising after the acupuncture sessions.

Conclusions Acupuncture plus diclofenac is more effective than placebo acupuncture plus diclofenac for the symptomatic treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of joint disease, and its most common location is the knee.1 As the population ages or the disease worsens, osteoarthritis is associated with incapacity and a deteriorating quality of life owing to increased pain, loss of mobility, and the consequent loss of functional independence.2 As a result, osteoarthritis is often treated by medical or surgical intervention. The general increase in life expectancy means that increasing numbers of people present with osteoarthritis of the knee and have a reduced quality of life. Pain relief treatment is therefore a fundamental aspect in dealing with this illness.

In patients in whom standard medical practice (pharmacological treatment) is ineffective and who are not candidates for surgery (or who reject it), other pain management procedures should be considered.3 The role of acupuncture in osteoarthritis of the knee is still a matter of controversy, and few comparative studies of acupuncture and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for its treatment have been conducted.4 A recent systematic review concluded that a moderate degree of evidence exists that the effect of the acupuncture treatment could be due to the placebo,5 and further studies are therefore necessary to determine the true role of acupuncture.

We analysed the efficacy of acupuncture as a complementary therapy to the pharmacological treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee, with respect to pain relief, reduction of stiffness, and increased physical functioning during treatment; modifications in the consumption of diclofenac during treatment; and changes in patients' quality of life.

Materials and methods

Study design and subjects

We conducted a randomised, controlled trial with blinded evaluation and statistical analysis of results. It was carried out at the pain management unit in a public primary care centre in southern Spain, over a period of two years. The unit caters for the population of three primary care centres (75 000 inhabitants).

All the doctors at the three health centres in the study area received information about the study and inclusion criteria. We also informed them about the procedure for referring patients to the pain management unit, to be included in the selection process, and requested their collaboration in selecting patients to take part. Such patients were outpatients in whom osteoarthritis of the knee had been clinically and radiologically diagnosed according to the criteria of the American College of Rheumatology.6 The illness had to be symptomatic at the moment of selection. All patients gave their informed consent before taking part in the study.

The pain management unit applied the following criteria for inclusion in the study: patients had to be aged 45 years or older, with pain in one or both knees for the preceding three months or longer, and with radiological evidence of osteoarthritis of the knee (at least grade 1 according to the Ahlbäck classification,7 table 1). They had to be outpatients and willing and able to complete the study questionnaire. Criteria for exclusion were previous treatment with acupuncture; contraindication to medication with diclofenac; inflammatory, metabolic, or neuropathic arthropathies; severe concomitant illnesses that might interfere with the clinical evaluation of the patient; severe or generalised dermopathy; pregnancy or existing treatment with antineoplasic, corticoid, or immunosuppressive drugs.

Table 1.

Radiological classification of arthritis of the knee, according to Ahlbäck

| Ahlbäck grade7 | Anteroposterior stress radiograph | Lateral radiograph |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reduction of joint space | |

| 2 | Obliteration of joint space | |

| 3 | Tibial plateau attrition <5 mm | Posterior part of plateau intact |

| 4 | Attrition 5-10 mm | Attrition extends to posterior margin of the plateau |

| 5 | Severe subluxation of the tibia | Anterior subluxation of the tibia >10 mm |

The patients were divided into two groups, an intervention group treated with acupuncture plus diclofenac and a control group given placebo acupuncture plus diclofenac. We used a computer program to assign the patients randomly to one or the other group8; the invention group comprised 48 participants and the control group 49. We used a simple random allocation method. We sent out sealed opaque envelopes. Only the doctor applying the treatment was aware which group each patient had been assigned to, and he did not participate in any phase of the subsequent evaluation. We took precautions to maintain the confidentiality of the data concerning the participating patients. Before starting treatment, all patients observed a one week period during which they did not take any NSAIDs.

Treatment applied

Pharmacological

The patients in both groups received a bag with 21 tablets (50 mg) of diclofenac for the week (50 mg to be taken every 8 hours) and the instruction to reduce the dose if symptoms improved. We collected and counted up the unused medication. Patients with risk factors received gastroprotective drugs.

True and placebo acupuncture

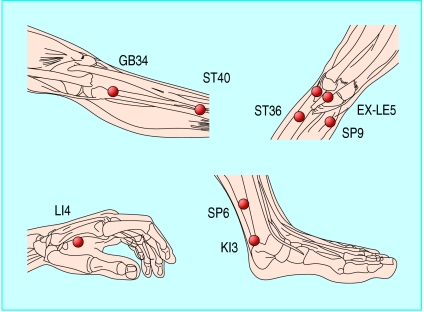

A doctor specialising in acupuncture (accredited by the Beijing University of Medical Sciences (China) and by the Scientific Society of Medical Acupuncture (ACMAS Huangdi, Spain)) selected acupuncture points on the basis of traditional treatment methods found to be effective for osteoarthritis of the knee.9,10 The standard acupuncture intervention entailed the insertion of sterile, single use, 30 gauge, and 45 mm length acupuncture needles into the local points GB34, SP9, EX-LE5, and ST36 (fig 1). The distal points were KI3, SP6, LI4, ST40. For each of the points in question the acupuncturist determined the patient's sensation of Deqi (an elicitation of needle sensation to check that the puncture was performed in the correct site). A WQ-10D1 electrostimulator was used to stimulate all the needles inserted into the local points electrically, in pairs. The treatment lasted 12 weeks, starting with visit 0 and ending with visit 11. The doctor carried out the final evaluation at visit 12, one week after the treatment had ended.

Fig 1.

Location of selected acupuncture points

The same specialist carried out the placebo acupuncture, at the same frequency and for the same duration as for the group receiving the true intervention. Retractable needles went into small adhesive cylinders, such that the needle was supported but did not perforate the skin.11 The acupuncturist then placed the needles over the same points as were used for the true acupuncture group. He connected the same pairs of electrodes and simulated the electrical connection.

Variables

Our general variables were patients' sociodemographic data and severity of illness (measured in duration of the osteoarthritis process in months, Ahlbäck score, body mass index).

Efficacy end points

We used as the primary efficacy end point the WOMAC index12 and its three subscales (pain (0-20), stiffness (0-8), and physical function (0-68)), pain in the knee on a visual analogue scale from 0 to 100, the dosage of diclofenac accumulated, and the profile of quality of life in the chronically ill (PQLC) instrument.13

Statistical analysis

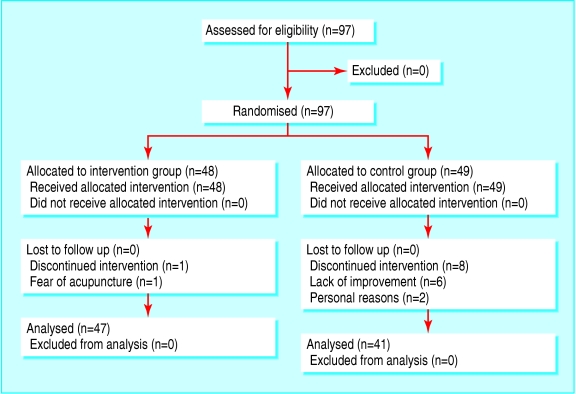

We used a freeware program14 to calculate the sample size for a mean total WOMAC score of 20 (SD 10) for the intervention group and of 33 (SD 28) for the control group, with bilateral contrast, a significance level of 0.05, and a power of 0.80. The minimum sampling size was 69. Assuming a maximum dropout rate of 20% we increased the minimum sample size to 83 patients. We selected 97 patients (fig 2).

Fig 2.

Flow of participants through the trial

We performed a baseline analysis of the two groups to seek clinically relevant differences, considering sociodemographics, severity of illness, and result. For the dropout analysis we used the Mann-Whitney U test for independent samples, together with Fisher's exact statistic (table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline data; comparison of the randomised groups by treatment type. Values are numbers (percentages) of participants unless otherwise indicated

| Total randomised distribution | ||

|---|---|---|

| Baseline data | Intervention group (n=48) | Control group (n=49) |

| Mean age in years (SD) | 65.7 (11.0) | 68.4 (9.1) |

| Age range in years | 45-91 | 48-90 |

| Men | 23 (11) | 10 (5) |

| Women | 77 (37) | 90 (44) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 79 (38) | 59 (29) |

| Separated | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Single | 2 (1) | — |

| Divorced | — | 2 (1) |

| Widowed | 17 (8) | 37 (18) |

| Education | ||

| None | 29 (14) | 51 (25) |

| Primary | 67 (32) | 45 (22) |

| Secondary | 4 (2) | 4 (2) |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Femoropatellar arthritis | 60 (29) | 63 (31) |

| Medial femorotibial arthritis | 65 (31) | 59 (29) |

| Lateral femorotibial arthritis | 29 (14) | 39 (19) |

| Ahlbäck score | ||

| 1 | 40 (19) | 29 (14) |

| 2 | 50 (24) | 43 (21) |

| 3 | 6 (3) | 18 (9) |

| 4 | 4 (2) | 10 (5) |

| Mean duration of osteoarthritis in years (SD) | 6.5 (8.7) | 8.5 (8.4) |

| Mean body mass index (SD) | 32.4 (6.1) | 33.6 (5.8) |

| Knee affected | ||

| Right | 29 (14) | 16 (8) |

| Left | 21 (10) | 16 (8) |

| Both | 50 (24) | 67 (33) |

| Mean baseline values (SD) | ||

| Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) osteoarthritis index: | ||

| WOMAC total | 57.1 (16.3) | 57.7 (18.6) |

| WOMAC pain | 12.4 (3.4) | 12.1 (4.0) |

| WOMAC stiffness | 4.1 (2.6) | 4.1 (3.0) |

| WOMAC function | 40.5 (12.2) | 41.5 (13.9) |

| Pain visual analogue scale | 58.9 (11.2) | 60.3 (13.7) |

| Profile of Quality of Life in the Chronically ill (PLQC): | ||

| Physical capability | 2.1 (0.6) | 1.9 (0.6) |

| Psychological functioning | 2.3 (0.5) | 2.2 (0.6) |

| Positive mood | 2.1 (0.7) | 1.9 (0.8) |

| Negative mood | 2.8 (0.8) | 2.8 (0.8) |

| Social functioning | 2.4 (0.5) | 2.2 (0.7) |

| Social wellbeing | 3.1 (0.4) | 3.0 (0.6) |

We used SPSS, version 11.5, to analyse the results by intention to treat, on the basis of the improvement in the total WOMAC score, on the pain visual analogue scale, and the PQLC score, using Student's t test for independent samples. We set P < 0.05 as the significance level for all the tests. For patients who withdrew, the score we used for each variable was the worst of the scores obtained for the intervention group and the best obtained for the control group. When a diagnosis of bilateral osteoarthritis of the knee had been made, the knee with the worse results at baseline was the knee we evaluated in the final analysis.

Results

Recruitment took place between January 2001 and December 2002. We selected 97 patients to participate in the study, all of whom agreed to take part. Table 2 lists the baseline characteristics of the patients; we found no clinically relevant differences in the variables that we analysed (total WOMAC, pain visual analogue scale, PQLC) at baseline. Of the nine patients who dropped out of the study, one out of 48 (2.1%) was in the treatment group and abandoned the programme because of fear of the acupuncture process, and eight of 49 (16.3%) were in the control group (six left due to lack of improvement and two for personal reasons; fig 2). The only significant difference between completers and non-completers was their age (they were six years older than non-completers; P = 0.03). Adverse effects after acupuncture treatment were limited to three patients who reported bruising at one of the acupuncture points (SP9).

In the intention to treat analysis, the WOMAC index presented a greater, and significant, reduction in the intervention group than in the control group (mean difference 23.9, 95% confidence interval 15.0 to 32.8; the magnitude of the reduction was greater in the subscale of functional activity (17.5, 11.0 to 24.0). The same result was observed in the pain visual analogue scale (reduction 26.6, 18.5 to 34.8). A reduction of 53.9 was observed in the total accumulated number of diclofenac tablets for the intervention group compared with the control group (24.7 to 83.1). The PQLC results indicate that acupuncture treatment produces significant changes in physical capability and psychological functioning (table 3).

Table 3.

Bivariant analysis by intention to treat. Data are mean (SD) scores

| Intervention group | Control group | Mean difference | P value (Student's t test for independent samples) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final pain visual analogue score | 10.6 (10.8) 26.3 | 37.2 (26.3) | 26.6 (18.5 to 34.8) | <0.001 |

| Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) osteoarthritis index (final scores)

|

|

|

|

|

| WOMAC total | 9.5 (13.7) | 33.4 (28.0) | 23.9 (15.0 to 32.8) | <0.001 |

| WOMAC pain | 1.7 (2.6) | 6.4 (5.8) | 4.7 (2.9 to 6.5) | <0.001 |

| WOMAC stiffness | 0.4 (1.3) | 2.1 (2.6) | 1.7 (0.8 to 2.5) | <0.001 |

| WOMAC function | 7.4 (10.3) | 24.9 (20.4) | 17.5 (11.0 to 24.0) | <0.001 |

| Total diclofenac | 85.4 (48.9) | 139.3 (89.6) | <0.001 | |

| Profile of quality of life in the chronically ill (PLQC)* | ||||

| Physical capability | 2.8 (0.7) | 2.5 (0.8) | 0.34 (0.05 to 0.63) | 0.021 |

| Psychological functioning | 2.7 (0.4) | 2.5 (0.6) | 0.22 (0.003 to 0.44) | 0.046 |

| Negative mood | 3.2 (0.7) | 3.1 (0.7) | 0.12 (−0.16 to 0.41) | 0.397 |

| Social functioning | 2.8 (0.5) | 2.7 (0.7) | 0.13 (−0.11 to 0.38) | 0.289 |

| Social wellbeing | 3.2 (0.5) | 3.2 (0.5) | −0.002 (−0.25 to 0.24) | 0.982 |

Range of PQLC items 0-4 (the higher the score, the better the quality of life).

Discussion

Mean results

Acupuncture as a complementary therapy to pharmacological treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee is more effective than pharmacological treatment alone, in terms of reducing pain and rigidity, and improving physical functioning and health related quality of life.

According to the criterion that an improvement in quality of life requires changes in at least two of the variables measured by the PQLC, the acupuncture provided to the intervention group was more effective than the placebo treatment in improving patients' quality of life.

True and placebo acupuncture

We decided to use a technique in the control group that did not require transcutaneous penetration, thus avoiding neurophysiological and neurochemical responses owing to the stimulation of cutaneous receptors; the intervention and control groups received treatments that were apparently identical: real acupuncture plus medication versus placebo acupuncture plus medication. By supplying both groups with medication, we sought to overcome possible ethical objections related to the role of the control group in the study.

Blinding procedure

Although the standard treatment was given for 12 weeks, participants who dropped out of the study were mainly from the control group, and only six people were lost to the study because their condition did not improve. To reinforce the blinding of the groups we expanded the criteria for selection of study patients to include the requirement that they should not have received previous acupuncture treatment; none of the participants lost to the study made any reference to belonging to one or the other of the two groups. Both the evaluation of the results and the statistical analysis were carried out in a blind fashion. These factors reinforce our belief that the blinding procedure applied was successful.

Limitations of the study

Observation of the sample groups over a period of 12 weeks may be insufficient to evaluate the effects of treatment in the medium term. Moreover, we did not test the patients' awareness of belonging to one or the other group, and so their complete “blindness” cannot be assured. Another possible limitation was the absence of techniques to verify the behaviour of the therapist, although the time spent with each patient was recorded; this was always close to the mean value (29.4 minutes).

Taking into account the duration of the study (12 weeks), we recorded patients' body mass index at the beginning and the end of the study, to evaluate the possible confounding effect of weight loss or gain. We found no significant differences.

We used different measurement techniques to evaluate the results obtained, testing whether the changes were all in the same direction and checking the consistency of the efficacy end points. We decided to use the categorical version of the WOMAC index because of the low cultural level of the population in the study area, and Spain's index of quality of life (PQLC) as a valid test for chronically ill patients. We considered the “total accumulated consumption of diclofenac” an objective variable with which to measure the responses of the two sample groups. As osteoarthritis is still an incurable illness, treatment is fundamentally aimed at improving the patient's quality of life, which is why we included this variable in the study. The consistency of the results is endorsed by the fact that the different aspects of physical functioning improved, according to both indices, the WOMAC and the PQLC. It is noteworthy that the evaluators were unaware of the group to which the patient had been assigned.

Comparison with other studies and outlook

The studies published to date have methodological deficiencies in the description and application of the method chosen for randomisation, the concealment of the treatment assignation scheme, the homogeneity of the groups to be compared, the control of co-interventions, the lack of control over participants' compliance with medical instructions, and the “blinding” of patients and evaluators; and the heterogeneity of follow up periods was high.15-18 We attempted to improve on the methodological design of previous work, using a controlled, single blind, randomised trial with evaluation and analysis by third parties; the sample size was appropriate, and we controlled for possible confounding factors to a suitable degree; the professionals involved were suitably qualified; the placebo was adequately chosen; and the quality control of the materials used was ensured. We put particular emphasis on ascertaining the patient's sensation of Deqi when acupuncture was applied, and on describing secondary effects and the success of the technique in improving the patient's quality of life (PQLC).

Similar results were found in a small, short term and long term study, carried out by using the waiting list as the control group,15 and in another study that compared acupuncture plus baseline treatment with baseline treatment alone.16 In these studies, the absence of a placebo was a serious limitation to the validity of the conclusions; a third study incorporated a placebo, but in a hospital environment considered to be of low quality,5 whereas treatment was of greater intensity and duration of treatment was shorter.17 Another study compared acupuncture with sham acupuncture and found no statistically significant differences.18

Future research should extend the observation period after treatment in order to evaluate the duration of the improvement obtained and to establish treatment protocols.

What is already known on this topic

Acupuncture is widely used to treat chronic pain in osteoarthritis

Various clinical trials have indicated that acupuncture may be beneficial in treating the pain that arises from osteoarthritis

The placebos used in earlier trials, based on stimulation by transcutaneous penetration, achieved an excessively high success rate, possibly owing to the neurophysiological and neurochemical responses caused by stimulation of the cutaneous receptors

The methodological quality of previous studies, in terms of randomisation, homogeneity of the groups compared, blinding, and other factors, has been put into question

What this study adds

Acupuncture, as a complementary therapy to pharmacological treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee, is more effective than pharmacological treatment alone

This manifests itself in terms of pain relief, easing stiffness, and improving physical function

We thank M J Cano,J G de Hoyos,E Bassas, and C Andrés for their work in the conduct of the study, and J G de Hoyos for his useful comments on the initial protocol.

Contributors: JV, CM, EP-M, and JML designed the study. EV, MAB, MDP, OG, FS-R, IA, and RJ contributed to conduct of the study and writing of the paper. Statistical analysis was done by EP-M, CM, and JML. EV revised the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was partly financed by Servicio Andaluz de Salud (Grant No 192/99). The acupuncture materials and the drugs used in the study were provided by the Sevilla-Sur health district authorities.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Valme Hospital Ethics Committee, Seville.

References

- 1.Creamer P, Hochberg MC. Osteoarthritis. Lancet 1997;350: 503-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felson DT. The epidemiology of knee osteoarthritis: results from the Framingham osteoarthritis study. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1990;20(3 suppl 1): 42-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vas J, Perea-Milla E, Mendez C. Acupuncture and moxibustion as an adjunctive treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee—a large case series. Acupunct Med 2004;22(1): 23-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perrot S, Menkes CJ. Nonpharmacological approaches to pain in osteoarthritis. Available options. Drugs 1996;52(suppl 3): 21-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrandez IA, Garcia OL, Gonzalez GA, Meis Meis MJ, Sanchez Rodriguez BM. [Effectiveness of acupuncture in the treatment of pain from osteoarthritis of the knee]. Aten Primaria 2002;30(10): 602-8. (In Spanish.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum 1986;29: 1039-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahlbäck S. Osteoarthrosis of the knee. A radiographic investigation. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh) 1968;(suppl 72). [PubMed]

- 8.Silva Ayzaguer LC. Muestreo para la investigación en ciencias de la salud. Madrid: Ediciones Díaz de Santos; 1993.

- 9.Cheng XN. Chinese acupuncture and moxibustion. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1987.

- 10.Cobos R, Vas J. Manual de Acupuntura y Moxibustión. Beijing: Morning Glory; 2000.

- 11.Streitberger K, Kleinhenz J. Introducing a placebo needle into acupuncture research. Lancet 1998;352: 364-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol 1988;15: 1833-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siegrist J, Broer M, Junge A. Profil der Lebensqualität Chronischkranker (PLC). Göttingen: Hogrefe Verlag, 1996.

- 14.Brown BW. DSTPLAN calculations for sample sizes and related problems [computer program]. Version 4.2. Houston: University of Texas, 2000.

- 15.Christensen BV, Iuhl IU, Vilbek H, Bulow HH, Dreijer NC, Rasmussen HF. Acupuncture treatment of severe knee osteoarthrosis. A long-term study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1992;36: 519-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berman BM, Singh BB, Lao L, Langenberg P, Li H, Hadhazy V, et al. A randomized trial of acupuncture as an adjunctive therapy in osteoarthritis of the knee. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38: 346-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yurtkuran M, Kocagil T. TENS, electroacupuncture and ice massage: comparison of treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee. Am J Acupunct 1999;27(3-4): 133-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takeda W, Wessel J. Acupuncture for the treatment of pain of osteoarthritic knees. Arthritis Care Res 1994;7(3): 118-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]