Abstract

The theory of social diagnosis recognizes two principles: 1) extra-medical social structures frame diagnosis; and 2) myriad social actors, in addition to clinicians, contribute to diagnostic labels and processes. The relationship between social diagnosis and (de)medicalization remains undertheorized, however, because social diagnosis does not account for how social actors can also resist the pathologization of symptoms and conditions—sometimes at the same time as they clamor for medical recognition—thereby shaping societal definitions of disease in different, but no less important, ways. In this article, we expand the social diagnosis framework by adding a third principle, specifically that 3) social actors engage with social structures to both contribute to, and resist, the framing of a condition as pathological (i.e. medicalization and demedicalization). This revised social diagnosis framework allows for the systematic investigation of multi-directional, dynamic processes, formalizing the link between diagnosis and (de)medicalization. It also responds to long-standing calls for more contextualized research in (de)medicalization studies by offering a framework that explicitly accounts for the social contexts in which (de)medicalizing processes operate. To showcase the utility of this revised framework, we use it to guide our analyses of a highly negotiated diagnosis: intersex.

Keywords: diagnosis, medicalization, demedicalization, intersex, disorders of sex development, social determinants of health

The past decade has seen a surge of sociological attention dedicated to diagnosis. Mildred Blaxter originally called for a “sociology of diagnosis” as early as 1978, and Phil Brown reiterated that call again in 1990, but it was not until around 2009 that sociologists began delineating the contours of this new subfield. Since then, there has been an explosion of scholarly works and meetings dedicated to diagnosis both as a label and a social process inherent to the practice of medicine and the classification of diseases (see for example Davis, 2015; Jutel, 2009, 2011, 2015; Jutel and Dew, 2014; McGann et al., 2011).

In the context of growing sociological interest in diagnosis, Brown, Lyson, and Jenkins (2011) proposed their theory of social diagnosis to account for the relationship between larger social structural factors, and individual or community health. Social diagnosis, they argued, is social because (1) it diagnoses the social, political, economic and cultural structures that frame and contribute to disease and illness; and (2) it is conducted by various social actors (‘social diagnosticians’), including, but not limited to, clinicians, social scientists and lay people (Brown et al. 2011). For example, a social diagnosis of the recent lead poisoning crisis in Flint, Michigan might involve an appraisal of the political, economic and infrastructural factors that led to the crisis, as well as a careful examination of the various social actors (such as politicians, lay people and scientists) who contributed both to the poisoning itself and to raising awareness. In this way, social diagnosis serves as a framework for identifying the social determinants of health which, in addition to individual pathologies, lead to disease.

The relationship between social diagnosis and (de)medicalization, however, remains undertheorized, even though medicalization and demedicalization are central to diagnosis (Jutel, 2009; Jutel et al., 2014). Medicalization is the process by which a condition becomes recognized and treated as a medical problem, whereas demedicalization is the process by which a problem loses its medical definitions and solutions (Conrad, 1992). Scholars increasingly recognize that processes of medicalization and demedicalization occur simultaneously (making it difficult to entirely separate one process from the other) and that conditions can thus be characterized as more or less medicalized as social actors and forces change (Ballard and Elston, 2005; Bell, 2016; Conrad, 2013; Halfmann, 2012; Sulzer, 2015). Yet, while social diagnosis emphasizes how social actors “contribut[e] to the creation of…diagnosis,” (p. 941) and “collectively work to politicize…illness through social movements,” (p. 940) thereby working towards medicalization, it does not account for the myriad ways social actors also work towards demedicalization by resisting the pathologization of symptoms and conditions—sometimes at the same time as they clamor for medical recognition. In other words, it overlooks the multi-directionality of social processes that can shape diagnosis. For its part, the medicalization literature has called for more research on the social contexts in which (de)medicalization takes place (Ballard and Elston, 2005; Bell, 2016; Clarke et al., 2003; Conrad, 2013)—a central feature of the social diagnosis framework. Social diagnosis can therefore contribute to, and benefit from, studies of medicalization by shedding light on the social context in which social actors and structures can not only contribute to diagnoses but also push against them, thereby shaping the contours of diagnosis in different but no less important ways.

In this article, we revise the social diagnosis framework and forge a relationship between social diagnosis and (de)medicalization. In its original formulation, social diagnosis recognized two principles: 1) extra-medical social structures frame diagnosis; and 2) myriad social actors, in addition to clinicians, shape diagnostic labels and processes. In this revision, we add a third principle: 3) social actors engage with social structures to contribute to and resist, sometimes simultaneously, the framing of a condition as pathological (i.e. medicalization and demedicalization). Thus, a social diagnosis of Flint, Michigan using the revised framework would not only examine the political, economic and social factors and actors that contributed to the public health crisis, it would also be sensitive to the social forces and structures that resisted recognizing the situation as a crisis, including government officials and the laws protecting them (Phillips, 2016). Through this revision, we make explicit diagnostic resistance as a component of social diagnosis. Further, we situate (de)medicalizing processes in a framework that emphasizes social determinants of health and health behaviors, and the interplay between social actors and social institutions, structures, and ideologies (Braveman et al., 2011; Short and Mollborn, 2015), thus forging a connection between medical sociological subfields which promotes the examination of (de)medicalization in context.

To illustrate the revised framework, we conduct a social diagnosis of intersex, a site which renders visible the complex ways in which social actors shape and contest the pathologization of a condition. Intersex broadly refers to a variety of conditions that can present at birth or later in life whereby an individual’s chromosomes, hormones, or sexual organs differ from the ‘norm’ in a way that does not correspond to “typical definitions of male and female” (ISNA, 2008b). These individuals are usually given an umbrella diagnosis of “disorders of sex development,” or DSD, which is then further classified into one of over 20 DSDs to guide management and prognosis (Consortium, 2006). Social actors disagree, however, about whether sexual variation of this kind should be pathologized, despite considerable agreement (even among some doctors) that the construction of intersex as a diagnosis reflects a quandary of social categorization (Davis, 2015). Intersex is therefore a prime example of the kind of push-and-pull that makes medicalization more a question of scale than of discrete categories—a diagnosis in which structure is responsive to process—making it an appropriate case to illustrate the advantage of a revised theory of social diagnosis.

A brief note about terminology: throughout the paper we use the term ‘intersex.’ We acknowledge the appearance of consensus among medical professionals to use different terminology, namely “Disorders of Sex Development” (Alm, 2010), but we reflexively choose not to use the medical language of “disorders.” We recognize that not all scholars prefer the term intersex and that some intersex individuals do not prefer the term DSD (Davis and Murphy, 2013; Dreger and Herndon, 2009). We use the term intersex consciously, acknowledging its limitations (Holmes, 2009) and understanding that what ‘counts’ as intersex is also contested (Dreger and Herndon, 2009)—and socially constructed (ISNA, 2008b).

1. MEDICALIZATION AND DIAGNOSTIC RESISTANCE

1.1. Multidirectional Processes of Medicalization and Demedicalization

Recent debates in medicalization studies emphasize the inherent complexity, dynamism and multi-directionality of medicalization as a process or “continuous value,” rather than a binary either/or state (Clarke and Shim, 2011; Conrad, 2013, p. 197; Halfmann, 2012, p. 186). Demedicalization is an inherent and simultaneous part of this process, with medicalized categories contracting and expanding, resulting in degrees of medicalization (Conrad, 1992, 2013; Halfmann, 2012). As biomedicine has advanced, scholars have adapted their studies of medicalization to include biomedicalization, a term that describes transformations in medical phenomena and the remaking of new identities using technoscientific medicine. This perspective also recognizes “the increasingly complex, multisited, multidirectional processes of medicalization,” (Clarke et al., 2003, p. 162) by examining our growing reliance on technoscientific means to transform, rather than merely control, medical phenomena (Clarke and Shim, 2011, p. 173).

Medicalization may be multi-directional, but only a small portion of studies examine the aspect of social deconstruction of disease (Crossley, 2004), partly because counter-efforts to medicalization rarely amount to “organized social resistance” (Conrad, 2013, p. 208) in the way that medicalization efforts sometimes do (see Barker, 2002). Contesting medicalization refers to “challenging the aspects of the creation and application of medical diagnostic categories and treatments,” (Conrad and Stults, 2008, p. 324) and can include resistance towards being labeled as sick (Cheung and Delfabbro, 2016), reluctance to using medical therapies (Malacrida, 2004), and debates over whether a condition should be considered problematic (Grinker and Cho, 2013). Medical professionals can also resist diagnoses, as with the British Psychological Society’s critiques of the DSM-5, which, in their view, pathologizes “natural and normal responses” to experiences “which do not reflect illnesses so much as normal individual variation” (British Psychological Society, 2011, p. 2). Diagnostic resistance is thus a significant, if less exposed, social force that can occur alongside the well-known engines of medicalization like biotechnology and consumerism (Conrad, 2005).

1.2. Decontextualized: Bringing Structure Back In

As with most studies of medicalization, however (Ballard and Elston, 2005; Bell, 2016; Clarke et al., 2003; Conrad, 2013), resistance remains decontextualized. Few studies systematically analyze the ways in which social structures contribute to or support these social processes (Crossley, 2004). Conrad (2013) and Bell (2016), for example, have respectively lamented the absence of research on the political economy of (de)medicalization, and the paucity of scholarship on disparities therein. Yet social structures are important sources of inertia—or resistance to social change—that lend stability to social practices and can perpetuate inequalities. Insurance companies, for example, can provide “inadvertent” resistance to medicalization by refusing to pay for certain conditions, such as fertility treatments (Bell, 2016; Conrad, 2013). Federal funding structures can also impact a condition’s recognition as a formal diagnosis, since social movements tend to form around diseases that have already received NIH funding (Best, 2012). These examples illustrate the range of social forces that operate along the medicalization-demedicalization continuum.

The current social diagnosis framework does not address this level of complexity in the processes of (de)medicalization. While Brown et al. (2011) acknowledge that contestation exists in diagnosis, they take a contested illness perspective which emphasizes how social actors “work to politicize...illness through social movements” in order to “democratize the production of scientific knowledge and then use that transformed science as the basis for demands for improved research on disease etiology, treatment, prevention, and stricter regulation” (2011, p. 940). This perspective, however, focuses on efforts to seek medical recognition for a disease or an etiology—it does not account for resistance to what is deemed medical. Conrad and Stults (2008) distinguish between contesting medicalization and contested illnesses by noting: “[W]hile most studies of medicalization express concerns about overmedicalization, contested illness in general suggests the desire for more medicalization” (p. 332). Their observations lead them to call for more research combining both types of resistance (2008, p. 334).

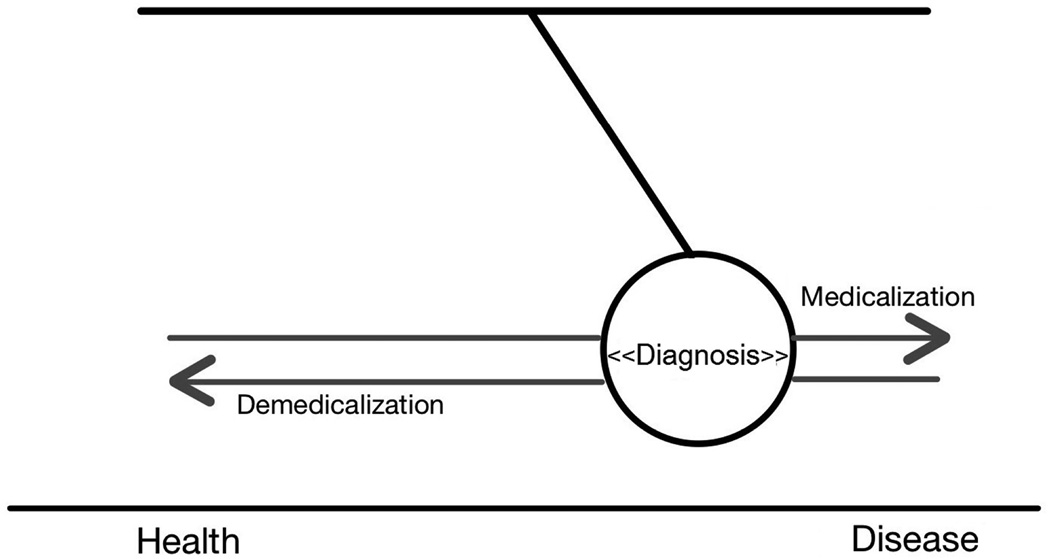

The revised social diagnosis framework adopts this integrated perspective by incorporating a multi-directional and dynamic view of the processes of (de)medicalization that shape diagnostic categories. To be sure, “medicalization” and “diagnosis” are distinct. Jutel (2009) pointed out the need to distinguish the two terms, and described medicalization as a process “that is aided in its accomplishment by diagnosis as a classification tool” (p. 285). If we think of their relationship as a pendulum, diagnosis is the product (and sometimes the catalyst) of the social forces of medicalization and demedicalization, i.e. the push and the pull led by social actors and structures that shapes what counts as diagnostic categories (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The relationship between diagnosis and (de)medicalization as a pendulum, where diagnosis is a product and a catalyst of the social forces of medicalization and demedicalization.

By adding a third principle that explicitly incorporates resistance, we enhance the social diagnosis framework by more fully integrating the range of dynamic social processes (both medicalization and demedicalization) that shape diagnoses. The revised social diagnosis framework therefore calls for a systematic investigation of the whole spectrum of (de)medicalization forces, thus formalizing the link between diagnosis and medicalization. In so doing, it also emphasizes the contextualization of diagnosis, thereby offering a framework to help situate studies of medicalization.

2. THE CASE OF INTERSEX

To showcase the utility of this revised framework, we use it to guide our analyses of a highly negotiated diagnosis: intersex. This analysis is based on a review of the socio-cultural literature on intersex published between 1990 and 2015 as identified through a keyword search on the terms “intersex” or “DSD” and derivatives in the title or abstract fields on Web of Science, as well as a backward and forward reference search of these documents to identify additional relevant materials. Then, using social diagnosis principles, we identified key actors and structures in the intersex debate, and their contributions to (de)medicalization processes. This analysis revealed highly complex negotiations between social actors over the pathologization of this condition. It exemplifies how social actors can engage with social structures to both contribute to and resist the framing of a condition like intersex as pathological.

Below, we examine the sometimes-conflicting perspectives of four major groups of social actors in the intersex debate: clinicians, activists and scholars, parents and intersex individuals. To be sure, some of these social actors overlap; patients are sometimes also activists and scholars (see for e.g. Davis, 2015), though the degree of overlap is difficult to measure and can change over time. Alliances between groups (such as doctors and activists) can also change over time, such that groups align at certain points and diverge at others. We therefore use this categorization of social actors as a heuristic or ideal type to illustrate some of the complexity involved in the debates over intersex. We emphasize that this heuristic does not fully represent the fluid, changing, and multidimensional identities and perspectives of the numerous individuals involved. In addition, per the revised social diagnosis framework, we pay close attention to the heterogeneous interests within these groups (and acknowledge the fluidity of individual views over time), which can result in forces that push for intersex’s medicalization and demedicalization simultaneously. We then place these social actors into context by examining the social structures that both constrain and empower them to shape the intersex debate, including technology, law/government, and socio-cultural norms surrounding sex/gender. Finally, we conclude with implications for the sociology of diagnosis and medicalization studies.

2.1 Social Actors

2.1.1 Clinicians

Until recently, when a child was born who could not easily be assigned a sex according to the sex/gender binary, clinicians would typically run tests to determine a “true” sex, and perform medical interventions to align physical variation with this sex/gender assignment. Since 2004, however, the medical community has shown interest in reforming practices related to the management of intersex conditions, moving away from the idea that the immediate surgical or medical erasure of any sex ambiguity is best practice (M. Diamond and Beh, 2006). In 2006, the American and European pediatric endocrine societies issued their landmark “Consensus Statement on the Management of Intersex Disorders” aimed at regulating approaches utilized by physicians (Lee et al., 2006). For the first time, in drafting this consensus, clinicians invited members of patient advocacy groups to join them in discussing various aspects of intersex management (Hughes, 2015) though some have described the advocates’ involvement as “limited, and at best, tokenistic,” (Karkazis as cited in Clune-Taylor, 2010, p. 153), with only two patient advocates present at the meetings.

On the surface, the Consensus Statement promised a more “holistic,” less narrowly medicalized approach than was previously espoused by clinicians (Hughes, 2015). For example, its recommendations for surgical intervention only in cases of “severe virilization” were more sensitive to patients’ rights to fertility and sexual pleasure. The Statement also shifted the surgical focus from cosmetic to functional interventions, citing the risks of repeated surgery. A more general awareness of patients’ rights was palpable throughout the Statement, including guidelines for the appropriate use of medical photography. These changes reflected a marked departure from previous approaches which heavily insisted on ‘normalizing’ genitalia and represented a degree of success for advocates who fought to transform medical practices.

But as patients’ well-being came into the foreground of the Statement, medical authority gained strength in the background, especially through the proposed change in nomenclature from “intersex” to “disorders of sex development” (DSD). This term originated from a separate meeting of activists, parents, and clinicians sponsored by the Intersex Society of North America (see below), but it granted physicians continued control over the pathological framing of sex variation, thereby reinforcing their jurisdiction over intersex (Davis, 2011). While some scholars have called for more emphasis on variation than disorder or ambiguity (Kessler, 1998; Reis, 2007), the acronym ‘VSD’ was discounted because it is already used in the medical lexicon to denote “Ventricular Septal Defect” (Hughes, 2015). Thus, despite being touted as “sensitive to the concern of patients,” (Lee et al., 2006, p. e488), the new nomenclature has been criticized for reflecting and advancing physicians’—not patients’—interests (Davis, 2011, 2014).

The framing of intersex as a medical problem helps justify physicians’ role as deciders of what counts as male and female in society (Holmes, 2009)—a powerful position derived from cultural views about sexual dimorphism. When clinicians attempt to ‘uncover’ a baby’s sex through the extensive diagnostic evaluation of chromosomes, hormones and sex organs, they speak of finding the ‘true’ sex, when they have simply made a recommendation about what they believe to be the most ‘appropriate’ sex (Zeiler and Wickstrom, 2009). As Vidal and colleagues (themselves physicians) write about surgical treatments for DSDs, “The challenge is to outline the future individual identity of the child in the postnatal period using these indicators,” (2010, p. 311, emphasis added) suggesting it is physicians’ responsibility to divine what the body is truly saying, and render it less ambiguous. This position of power was therefore maintained and medicalization was solidified as clinicians kept control over, and arguably strengthened, their jurisdiction over intersex in the 2006 Consensus Statement, despite inroads made by patient advocates towards changing medicalized approaches.

2.1.2 Activists and scholars

Activists and scholars joined forces in the 1990s to counter medicine’s treatment of intersex, and offer support and resources to intersex individuals (Chase, 1998; Preves, 2003). The Intersex Society of North America (ISNA)—now Accord Alliance (ISNA, 2008a)—was one of the most vocal groups in the U.S., fighting to alter social norms and recognize the rights of intersex individuals (Chase, 1998). ISNA denounced physicians for framing intersex as a medical emergency—calling it instead a social emergency (Davis and Murphy, 2013; Karkazis, 2008). They advocated treating intersex bodies not as “diseased, only different,” (Chase, 1998, p. 195), emphasizing how rarely intersex actually constitutes a medical emergency (Kessler, 1998; Preves, 2002). The diagnosis of intersex, in their opinion, was the product of “regulatory mechanisms of normalization,” (Clune-Taylor, 2010, p. 161) and they called for the halting of medical interventions that sought the erasure of anatomical variation (Feder, 2009b; Holmes, 2009; Machado, 2009). These views represented considerable consensus within the intersex activist community in the 1990s (Dreger and Herndon, 2009, p. 205), which allowed the demedicalization movement to flourish.

In 2005, before the pediatric endocrinology Consensus meeting, ISNA convened a Consortium of 45 individuals (24 clinicians and 21 activists/scholars, including adults and/or parents of individuals with intersex conditions), to produce a set of clinical guidelines emphasizing patient-centered approaches to DSD management. This is an extraordinary example of how the actions of one group (social activists) can affect the actions of another (clinicians) in shaping a diagnosis by producing clinical guidelines that challenge extant medical approaches— an important hallmark of our revised social diagnosis framework, which recognizes how social actors resist medicalization.

Importantly, despite their emphasis on patient-centered approaches, these Guidelines also proposed several changes to the medical management of intersex which paradoxically contributed to its medicalization. Perhaps the most important of these changes was the aforementioned revision to the nomenclature. Sociologists have argued that for a problem to be medicalized, it need not have a medical solution, but it does require a medical definition (Conrad, 1992; Halfmann, 2012). While the Guidelines strongly condemned early surgery, and urged clinicians to consider whether interventions were truly in their patients’ best interest (which contributed to intersex’s demedicalization), they still championed the term DSD which cemented the framing of intersex as a disease. ISNA’s Consortium is credited with having coined Disorders of Sex Development as a replacement for intersex (Dreger and Herndon, 2009). However that same term has been criticized for framing intersex as a ‘disorder’ (Holmes, 2009), and conveying the notion that intersex bodies are defective: “If using the word disorder connotes a need for repair, then this new nomenclature contradicts one of intersex activism’s central tenets: that unusual sex anatomy does not inevitably require surgical or hormonal correction” (Reis, 2007, p. 539). By supporting the name change to DSD, among other changes, the Consortium therefore bolstered intersex’s pathological framing, despite ISNA’s long history of denouncing medicine’s approach to intersex.

Disagreements about the desirability of the revised DSD diagnosis, the Guidelines, and their implications are manifestations of the considerable heterogeneity among activist individuals and organizations. Some activists have heavily criticized the Consortium for betraying the intersex community by endorsing practices that “induce docility rather than confer capacity” (Clune-Taylor, 2010, p. 170). In response, some advocates have described this apparent paradox as a necessary, pragmatic effort to compromise and build alliances with the medical profession (Dreger and Herndon, 2009; ISNA, 2006). Others have alluded to the power of diagnosis for unlocking access to resources, noting that to receive healthcare, intersex has to be framed using a “pathologizing term” (Feder, 2009a, p. 239). Supporters also argue that the new nomenclature normalizes intersex conditions by referring to them as a disorder “just like any other” rather than being all-encompassing of individuals’ identity like intersex (Dreger and Herndon, 2009; Feder, 2009a, 2009b).

These debates have left the scholar-activist community somewhat splintered. The considerable agreement among activists against the medical establishment forged in the 1990s has been replaced with disagreement surrounding the new terminology (Davis, 2014; Karkazis, 2008; Reis, 2007). These disputes are central in the revised social diagnosis approach, illustrating the multi-directional and dynamic processes of (de)medicalization, and the conjoint manufacturing of ‘pathology’ that reflects intersections and contradictions between and among clinicians, scholars, and activists—individuals who often occupy more than one of these roles at once.

2.1.3 Parents

Meanwhile, upon the birth of an intersex child, parents are often thrust unwittingly into this debate as they are confronted with “a world informed by the premise of defect, not of neutral variation,” (Holmes, 2009, pp. 17–18). For parents who understand sex in binary terms, intersex can be disorienting (Zeiler and Wickstrom, 2009), and even devastating (Gough et al., 2008). Some parents supported the change in nomenclature precisely because the notion of being “in between sexes” made them feel alienated and uncomfortable (Holmes, 2011; Reis, 2007); this was a reason cited by the Consortium for replacing intersex with DSD (Dreger and Herndon, 2009). Others have pointed out that adapting terminology to placate parents draws emphasis away from the intersex person themselves (Reis, 2007).

Given their concern and confusion, many parents turn to medicine to make sense of their baby’s ‘dis’-order, find clues about the ‘true’ sex, and ultimately ‘fix’ their child (Gough et al., 2008; Zeiler and Wickstrom, 2009). In this way, they contribute to the medicalization of intersex by demanding medical solutions to socially-uncomfortable situations. At the same time, scholars observe that it is reasonable for parents to be alarmed, and to accept, rather than challenge, prevailing dimorphic and essentialist understandings of sex, when medical professionals present them with a socio-medical emergency (Davis and Murphy, 2013). And while decisions about medical interventions are ultimately left up to the parents, they remain heavily influenced by medical professionals (Davis and Murphy, 2013; Streuli et al., 2013)—yet another instance of spill-over between actors.

The desire to be good parents also influences decisions to consent to genital surgery. Informed by cultural beliefs about sex and gender, parents perceive ‘ambiguous’ genitalia as problematic and often decide about the need for surgery on the basis of those beliefs (Sanders et al., 2008). At the same time, parents are left to do much of the identity work after sex has been determined/assigned (Zeiler and Wickstrom, 2009). Some parents choose surgery to reorient themselves and promote their child’s acceptance by society, while others refuse surgery and choose to reorient their perspective by viewing sex more fluidly (Zeiler and Wickstrom, 2009). In this way, some parents contribute to intersex’s medicalization by demanding medical answers, while others contribute to its demedicalization by challenging the sex binary—an important social structure in this debate, as addressed below.

2.1.4 Intersex individuals

Finally, we come to the individuals whose bodies are at the center of this debate. Despite efforts to include intersex individuals in the Consortium and Consensus Statement, their voices are rarely heard in the context of discussions about their bodies, since most decisions are made when they are infants (Alm, 2010). Thus, they are often caught between the interests and concerns of their parents, doctors, scholars, and activists when they are young, and sometimes shape debate and diagnosis as they grow older. Some intersex individuals would prefer to abolish the dichotomous representation of sex, while others support its maintenance (Meyer-Bahlburg et al., 2004). Still others want to create new categories that accommodate their variations without pigeonholing them into either one sex or another (Chau and Herring, 2002). Almost all want full disclosure from clinicians regarding assessments (Alderson et al., 2004)—a courtesy that sadly remains far from universal (D'Alberton, 2010).

Intersex individuals vary in their perceptions of the new terminology (Davis, 2014). One study of patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), a common intersex condition, found that a large majority disliked the term ‘DSD’ and/or did not identify with it (Lin-Su et al., 2015). Over three-quarters felt it had a negative effect on the CAH community. Another study found that intersex individuals who endorsed the new DSD terminology were more inclined to express feelings of ‘abnormality’ than those who rejected the term (Davis, 2014). While Consortium scholars maintained that the term DSD was less essentializing than intersex, some intersex individuals found the term ‘disorder’ to be even more so. A gap may therefore remain between practitioners’ (and activists’ and parents’) satisfaction on the one hand, and patients’ on the other (Lin-Su et al., 2015).

Intersex individuals thus variously contribute to and resist the medicalization of intersex. Many are critical of surgical normalization (Chau and Herring, 2002; Preves, 2003), rejecting the idea that intersex requires a medical solution. Others prefer early surgery and do not regret the intervention (Fagerholm et al., 2011). One study found that intersex individuals constructed narratives that normalized their difference by either minimizing it or emphasizing variation among others, and situating their own difference as part of a constellation of sex variation (Guntram, 2013). In this way, they reinforce, resist, and reshape the two-sex imperative, thereby also contributing to the debate surrounding the (de)medicalization of intersex.

2.2 Diagnosing Social Structures

As we have demonstrated, multiple actors negotiate the diagnosis of intersex. The revised social diagnosis framework, however, recognizes that these actors do not operate in isolation; they are situated within social structures that shape the ways they challenge or uphold the status quo. Next, we describe three such structures - technology, law and governments, and socio-cultural norms – as they relate to the intersex debate.

2.2.1 Technology

As technology and medicine have advanced, so have our understandings of sex and our abilities to pathologize intersex. Until relatively recently, intersex bodies were generally “unremarkable” by society, and effectively non-medicalized (Dreger and Herndon, 2009, p. 201). Today, technology has fundamentally altered our responses to them (D. A. Diamond and Yu, 2011). Early detection of intersex conditions, for example, is possible through amniocentesis, leading to early parent and physician engagement, including selective abortion (Holmes, 2002). Families with a history of CAH can begin prophylactic treatments of dexamethasone as of the fourth week after conception, to prevent genital abnormalities in XX individuals (Fausto-Sterling, 2000). Parents can also use in-vitro fertilization and pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) to avoid conceiving a child with intersex traits (Sparrow, 2013). Together, these developments reflect increasing biomedicalization, which emphasizes the (re)making of new identities by technoscientific means (Clarke et al., 2003).

Technology also limits medical interventions and thus shapes what are considered the markers of ‘true’ sex. For example, it remains difficult to surgically construct a socially-acceptable penis (Vidal et al., 2010), which has historically served as the primary criterion for raising intersex children as male or female (Chau and Herring, 2002; Fausto-Sterling, 2000). Over the past three decades, however, fewer chromosomally-male children have been surgically assigned to the female sex, a practice which has been attributed to modest technological improvements, as well as shifts in attitudes among new urologists (Kolesinska et al., 2014). Therefore, as technology changes, less primacy is placed on the genitals as primary determinants of ‘true sex,’ which affects intersex’s medicalization.

Still, technology remains operator-dependent and almost exclusively within medicine’s jurisdiction, reflecting back society’s fascination with sexual dimorphism. While advances in technology illuminate a wider range of variation in sex development across individuals—thus enabling medical professionals to ‘see’ many sexes—these differences are often paradoxically reduced through medical technology used to maintain the ideal sex binary (Hester, 2004). PGD, for example, has been heavily criticized for this reason by intersex scholars and activists (Davis, 2013), with some calling it a form of eugenics designed to “reinforce the inadequate sex binary…” (Orr, 2015, np). With the revised social diagnosis framework, we recognize that social actors’ responses to intersex are shaped by the results produced by this very same technology, and the lenses with which they create and interpret those results.

2.2.2 Law and government

Law and governments provide institutional frameworks for both construing intersex as pathological and contesting its status as a disease. Historically, the law concerning so-called ‘hermaphrodites’ in most jurisdictions did not impose a particular sex on its subjects, but rather upheld that which was adopted (Fausto-Sterling, 2000, p. 36). Governments and legal institutions required two sexes to distinguish those who could vote, own property, and testify in court (Chau and Herring, 2002; Uslan, 2010). Today, many of these same dimorphic divisions are upheld, partly because of the social anxieties associated with maintaining a heteronormative sex/gender dichotomy (Meadow, 2010).

Some international bodies, however, including The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR, 2015) and the U.S. Department of State (Kirby, 2016), have begun expressing their solidarity for intersex rights, thereby influencing broader dialogues about the condition. Some governments have also begun legalizing third sexes/genders for intersex or transsexual/transgendered individuals (Pandey, 2014). In 2013, Germany became the first European country to allow parents to register their children as being of ‘indeterminate sex,’ rather than forcing them to choose either male or female (BBC News, 2013). In most American jurisdictions, however, only two options exist for sex on official documents: male and female (Currah and Moore, 2009).

When it comes to consent for genital surgery, American law dictates that medical interventions can only take place with the patient’s consent, or, in the case of minors, with parental consent. In the latter case, the intervention must be (1) necessary, and (2) in the patient’s best interest (Chau and Herring, 2002; Uslan, 2010). For intersex children, however, critics argue that the evidence does not conclusively support either of these two caveats, creating a “categorical conflict” (Uslan, 2010). This has led some patient advocacy groups to seek injunctions against parents seeking genital surgery for their children (Warne and Mann, 2011; Westenfelder, 2011). Colombia and Malta have already instituted laws against performing genital surgery before a child is able to provide consent, except in extraordinary circumstances (Greenberg and Chase, 1999; OII Europe, 2015). The hope is that these laws will help affirm that intersex individuals do not need ‘fixing’ or ‘repairing’ (OII Europe, 2015), thereby helping demedicalize the condition.

In the U.S., patient advocates are also using the courts to challenge unnecessary surgeries. An intersex legal rights group has filed a first-of-its-kind lawsuit against physicians and state actors for performing irreversible surgery on an infant (‘MC’) without adequately informing his guardians about the risks (interACT, 2015). This suit exemplifies how social actors like activists, use the law (a social structure) to challenge doctors (other social actors) who impose medical solutions to problems stemming from social norms.

2.2.3 Social and cultural norms

Ultimately, societal beliefs in a rigidly dimorphic approach to sex are at the root of the medicalization of intersex (Davis, 2011). Intersex threatens the very core of the sex/gender binary, prompting a medical response aimed at controlling this ‘social problem’ (Davis and Murphy, 2013; Zola, 1978 [2009]). Indeed, the very need to ‘have’ a sex that is recognized by others has prompted some scholars to argue that all individuals have an ethical right to a sex (Hester, 2004). This translation of a cultural imperative into a basic ethical imperative gives rise to medical emergencies when sex development is ‘atypical’ (Davis and Murphy, 2013).

Nowhere are the culturally- and socially-specific foundations of these norms clearer than when looking at other societies that do not espouse the same rigidly dimorphic views. The term guevedoche, for instance, is used in the Dominican Republic to represent a small but significant group of individuals who are born phenotypically female but whose physical appearance virilizes at puberty due to their male genotype. Other examples of third genders include the kwolu-aatmwol of New Guinea, the two-spirit (formerly known as berdache) in Native American communities and the hijra in Southeast Asia (Herdt, 1994). To be sure, these groups have each experienced varying degrees of discrimination for not being ‘fully’ male or female, and continue to fight for legal recognition (Scobey-Thal, 2014). These cultures reveal, however, that a strictly dimorphic conceptualization of sex/gender reflects sociocultural circumstances, as such dimorphic views do not exist everywhere and always. They also suggest that societies can account for variation non-medically by relaxing the two-sex system. Medicalization, therefore, is but one social response to intersex.

Times are changing, however. The Oxford English Dictionary recently announced the addition of “gender-fluid” to its pages to describe an individual who identifies as non-binary (Steinmetz, 2016). As with the term ‘queer,’ which was claimed and redefined by the gay community (Crossley, 2004), this addition exemplifies how changing socio-cultural norms affect language. New language may well support diagnostic resistance by highlighting the problem of social categorization posed by intersex, rather than reinforcing its medical status.

3. CONCLUSION

We have used the case of intersex as a negotiated diagnosis to illustrate the advantages of a revised theory of social diagnosis. Recall that our goal was to add a third principle to the theoretical framework that recognizes how social actors engage with social structures to contribute to and resist the medicalization and demedicalization of symptoms and conditions. Our analysis has shown how the pathologization of variation in sex characteristics reflects this principle. In their efforts to demedicalize intersex, for example, social activists and scholars simultaneously reaffirmed its medicalization by making pragmatic concessions to medicine in advocating for the term “disorders of sex development.” In response to growing criticism from activists and scholars, clinicians also questioned some of their own practices in the Consensus Statement of 2006. A traditional social diagnosis might have focused on the social actors and factors that contributed to intersex’s classification as a disease; in contrast, our analysis using the revised framework, presents a fuller picture by also explicitly accounting for instances of resistance. The case of intersex shines a light on the significant interdependencies between social actors in the social framing of a diagnosis. It also reveals how such spillover is reflected in (de)medicalization, complicating previous understandings of how diagnoses are negotiated.

Further, these analyses reveal considerable heterogeneity among social actors. The introduction of the new DSD terminology disrupted earlier consensus from the 1990s among activists regarding their critique of the medical approach. Activists joined medical discussions over the definition and treatment of intersex, but at the cost of dividing up the scholar-activist community. Parents and intersex individuals, who are sometimes also activists, variously support or reject the new terminology, adding additional complexity to the debate. In this way, not only do social actors contribute to both medicalization and demedicalization, but different people within the same group might do it differently, representing a diversity of perspectives.

Finally, the analyses illustrate how diverse social actors are influenced by, and use, social structures to advance their positions. Innovations in technology have made intersex more readily diagnosable, and thus more amenable to medical interventions. At the same time, technological advancements in surgery have helped shift physicians’ focus from the genitals when adjudicating cases of intersex, thereby leading to incremental changes in the standard of care. Social structures thus serve to both preserve the status quo and challenge it. The law offers another excellent example; while most jurisdictions have codified the sex-gender binary (by requiring that parents choose only one of two sexes on birth certificates, for instance), social activists are increasingly using the courts to challenge these views, along with current medical definitions and practices surrounding intersex. We therefore maintain that a comprehensive social diagnosis framework is not complete without a dynamic, relational, and multi-directional view of both social actors and social structures as they negotiate diagnoses.

Revising the social diagnosis framework helps forge ties between a well-established area of medical sociology (medicalization) and a relatively new one (diagnosis). It also emphasizes the social contexts in which (de)medicalization occurs, providing a framework that is responsive to long-standing calls for more contextualized research (Ballard and Elston, 2005; Bell, 2016; Clarke et al., 2003). While intersex may be an especially contentious case, the complexity of social forces behind it are hardly exceptional. Future research can draw on the revised social diagnosis framework to identify the various moving parts involved in negotiations over medicalized definitions, thereby helping to capture the range of processes inherent to (de)medicalization, and provide researchers an analytic perspective to counter medicalization’s tendency to individualize social problems (Conrad, 2013). As the sociology of diagnosis approaches its adolescence as a subfield, it will undoubtedly benefit from brokering new connections and relationships like these to more established areas in medical sociology and beyond.

Highlights.

Social diagnosis draws attention to the extra-medical factors that shape diagnosis

Social diagnosis (SD) processes are multilevel, multi-directional, and dynamic

Actors and structures promote and resist pathological framing ((de)medicalization)

The SD framework is revised to account for resistance to medicalization

The case of intersex is used to demonstrate the utility of the new framework

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Works Cited

- Alderson J, Madill A, Balen A. Fear of devaluation: Understanding the experience of intersexed women with androgen insensitivity syndrome. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2004;9:81–100. doi: 10.1348/135910704322778740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alm E. Contextualising intersex: Ethical discourses on intersex in Sweden and the US. Graduate Journal of Social Science. 2010;7(2):95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard K, Elston MA. Medicalisation: A Multi-dimensional Concept. Soc Theory Health. 2005;3(3):228–241. [Google Scholar]

- Barker K. Self-Help Literature and the Making of an Illness Identity: The Case of Fibromyalgia Syndrome (FMS) Social Problems. 2002;49(3):279–300. [Google Scholar]

- BBC News. Germany allows 'indeterminate' gender at birth. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-24767225.

- Bell AV. The margins of medicalization: Diversity and context through the case of infertility. Social Science & Medicine. 2016;156:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best RK. Disease Politics and Medical Research Funding: Three Ways Advocacy Shapes Policy. American Sociological Review. 2012;77(5):780–803. [Google Scholar]

- Blaxter M. Diagnosis as Category and Process: The Case of Alcoholism. Social Science & Medicine. 1978;12:9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P, Egerter S, Williams DR. The social determinants of health: coming of age. Annual Review of Public Health. 2011;32:381–398. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- British Psychological Society. Response to the American Psychiatric Association: DS-5 development. 2011 Retrieved from https://docs.google.com/viewer?url=http%3A%2F%2Fapps.bps.org.uk%2F_publicationfiles%2Fconsultation-responses%2FDSM-5%25202011%2520-%2520BPS%2520response.pdf.

- Brown P. The Name Game: Toward a Sociology of Diagnosis. Journal of Mind and Behavior. 1990;11(3–4):385–406. [Google Scholar]

- Brown P, Lyson M, Jenkins TM. From diagnosis to social diagnosis. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;73(6):939–943. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase C. Hermaphrodites with attitude - Mapping the emergence of intersex political activism. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 1998;4(2):189–211. [Google Scholar]

- Chau PL, Herring J. Defining, assigning and designing sex. International journal of law, policy, and the family. 2002;16(3):63–85. doi: 10.1093/lawfam/16.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung SY, Delfabbro P. Are you a cancer survivor? A review on cancer identity. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2016;10(4):759–771. doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0521-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AE, Shim JK. Medicalization and Biomedicalization Revisited: Technoscience and Transformations of Health, Illness and American Medicine. In: Pescosolido B, Martin J, Rogers A, Pilgrim D, editors. Handbook of the Sociology of Health, Illness and Healing. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 173–199. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AE, Shim JK, Mamo L, Fosket JR, Fishman JR. Biomedicalization: Technoscientific transformations of health, illness, and US biomedicine. American Sociological Review. 2003;68(2):161–194. [Google Scholar]

- Clune-Taylor C. From intersex to DSD: The disciplining of sex development. Phaenex. 2010;5(2):152–178. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad P. Medicalization and Social Control. Annual Review of Sociology. 1992;18:209–232. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad P. The Shifting Engines of Medicalization. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46(1):3–14. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad P. Medicalization: Changing Contours, Characteristics, and Contexts. In: Cockerham CW, editor. Medical Sociology on the Move: New Directions in Theory. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2013. pp. 195–214. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad P, Stults C. Contestation and Medicalization. In: Moss P, Teghtsoonian K, editors. Contesting Illness: Process and Practices. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2008. pp. 323–336. [Google Scholar]

- Consortium on the Management of Disorders of Sex Development. Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Disorders of Sex Development in Childhood. 2006 Retrieved from http://www.dsdguidelines.org/files/clinical.pdf.

- Crossley N. Not being mentally ill. Anthropology & Medicine. 2004;11(2):161–180. doi: 10.1080/13648470410001678668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currah P, Moore LJ. "We Won't Know Who You Are": Contesting Sex Designations in New York City Birth Certificates. Hypatia-a Journal of Feminist Philosophy. 2009;24(3):113–135. [Google Scholar]

- D'Alberton F. Disclosing Disorders of Sex Development and Opening the Doors. Sexual Development. 2010;4(4–5):304–309. doi: 10.1159/000317480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis G. 'DSD is a Perfectly Fine Term': Reasserting Medical Authority through a Shift in Intersex Terminology. In: McGann P, Hutson DJ, editors. Sociology of Diagnosis (Advances in Medical Sociology) Vol. 12. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2011. pp. 155–182. [Google Scholar]

- Davis G. The Social Costs of Preempting Intersex Traits. The American Journal of Bioethics. 2013;13(10):51–53. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2013.828119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis G. The power in a name: diagnostic terminology and diverse experiences. Psychology & Sexuality. 2014;5(1):15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Davis G. Contesting Intersex: The Dubious Diagnosis. New York: New York University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Davis G, Murphy EL. Intersex Bodies as States of Exception: An Empirical Explanation for Unnecessary Surgical Modification. Feminist Formations. 2013;25(2):129–152. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond DA, Yu RN. Sexual Differentiation: Normal and Abnormal. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Partin AW, Peters CA, editors. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 10th. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2011. pp. 3597–3628. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond M, Beh HG. The Right to be Wrong: Sex and Gender Decisions. In: Sytsma SE, editor. Ethics and Intersex. London: Springer; 2006. pp. 103–113. [Google Scholar]

- Dreger AD, Herndon AM. Progress and Politics in the Intersex Rights Movement: Feminist Theory in Action. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 2009;15(2):199–224. [Google Scholar]

- Fagerholm R, Santtila P, Miettinen PJ, Mattila A, Rintala R, Taskinen S. Sexual Function and Attitudes Toward Surgery After Feminizing Genitoplasty. Journal of Urology. 2011;185(5):1900–1904. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.12.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fausto-Sterling A. Sexing the Body: Gender, Politics and the Construction of Sexuality. New York: Basic Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Feder EK. Imperatives of Normality: From "Intersex" to "Disorders of Sex Development". Glq-a Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 2009a;15(2):225–247. [Google Scholar]

- Feder EK. Normalizing Medicine: Between "Intersexuals" and Individuals with "Disorders of Sex Development". Health Care Analysis. 2009b;17(2):134–143. doi: 10.1007/s10728-009-0111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough B, Weyman N, Alderson J, Butler G, Stoner M. ‘They did not have a word’: The parental quest to locate a ‘true sex’ for their intersex children. Psychology & Health. 2008;23(4):493–507. doi: 10.1080/14768320601176170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JA, Chase C. Background of Colombia Decisions - Intersex Society of North America. 1999 Retrieved from http://www.isna.org/node/21.

- Grinker RR, Cho K. Border Children: Interpreting Autism Spectrum Disorder in South Korea. Ethos. 2013;41(1):46–74. [Google Scholar]

- Guntram L. "Differently normal” and “normally different”: Negotiations of female embodiment in women's accounts of ‘atypical’sex development. Social Science & Medicine. 2013 Dec;98:232–238. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfmann D. Recognizing medicalization and demedicalization: Discourses, practices, and identities. Health. 2012;16(2):186–207. doi: 10.1177/1363459311403947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdt GH, editor. Third Sex, Third Gender: Beyond Sexual Dimorphism in Culture and History. New York: Zone Books; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hester D. Intersexes and the end of gender: Corporeal ethics and postgender bodies. Journal of Gender Studies. 2004;13(3):215–225. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes M. Rethinking the meaning and management of intersexuality. Sexualities. 2002;5(2):159–180. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes M. Critical Intersex. Farnham: Ashgate; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes M. The intersex enchiridion: Naming and knowledge. Somatechnics. 2011;1(2):388–411. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes IA. Consequences of the Chicago DSD Consensus: A Personal Perspective. Hormone and metabolic research. 2015;47(5):394–400. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1545274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- interACT. Intersex Law and Policy. 2015 Retrieved from http://aiclegal.org/programs/project-integrity/

- ISNA. Why is ISNA using "DSD"? 2006 Retrieved from http://www.isna.org/node/1066.

- ISNA. Dear ISNA Friends and Supporters. 2008a Retrieved from http://www.isna.org/farewell_message.

- ISNA. Frequently Asked Questions. 2008b Retrieved from http://www.isna.org/faq/what_is_intersex.

- Jutel A. Sociology of diagnosis: a preliminary review. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2009;31(2):278–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2008.01152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutel A. Putting a Name to It: Diagnosis in Contemporary Society. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jutel A. Beyond the Sociology of Diagnosis. Sociology Compass. 2015;9(9):841–852. [Google Scholar]

- Jutel A, Dew K. Social Issues in Diagnosis: An Introduction for Students and Clinicians. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jutel A, Greenberg A, Katz Rothman B. Is this Really a Disease? Medicalization and Diagnosis. In: Jutel A, Dew K, editors. Social Issues in Diagnosis: An Introduction for Students and Clinicians. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2014. pp. 120–133. [Google Scholar]

- Karkazis KA. Fixing Sex: Intersex, Medical Authority, and Lived Experience. Durham: Duke University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler SJ. Lessons from the Intersexed. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby J. In Recognition of Intersex Awareness Day [Press release] 2016 Retrieved from http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2016/10/263578.htm.

- Kolesinska Z, Ahmed SF, Niedziela M, Bryce J, Molinska-Glura M, Rodie M, Weintrob N. Changes Over Time in Sex Assignment for Disorders of Sex Development. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):E710–E715. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PA, Houk CP, Ahmed SF, Hughes IA International Consensus Conference on Intersex. Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):E488–E500. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin-Su K, Lekarev O, Poppas DP, Vogiatzi MG. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia patient perception of 'disorders of sex development' nomenclature. International journal of pediatric endocrinology. 2015;2015(1):9. doi: 10.1186/s13633-015-0004-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado P. Intersexuality and sexual rights in southern Brazil. Culture Health & Sexuality. 2009;11(3):237–250. doi: 10.1080/13691050802233454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malacrida C. Medicalization, ambivalence and social control: mothers' descriptions of educators and ADD/ADHD. Health (London) 2004;8(1):61–80. doi: 10.1177/1363459304038795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGann P, Hutson D, Katz Rothman B, editors. Sociology of Diagnosis: Advances in Medical Sociology. Bingley: Emerald; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Meadow T. "A Rose is a Rose" On Producing Legal Gender Classifications. Gender & Society. 2010;24(6):814–837. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, Migeon CJ, Berkovitz GD, Gearhart JP, Dolezal C, Wisniewski AB. Attitudes of adult 46,XY intersex persons to clinical management policies. Journal of Urology. 2004;171(4):1615–1619. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000117761.94734.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHCHR. Opening remarks by Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein, United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights at the Expert meeting on ending human rights violations against intersex persons. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=16431.

- OII Europe. Statement by OII Europe: we applaud Malta’s new law. 2015 Retrieved from http://oiiinternational.com/3171/statement-oii-europe-applaud-malta-new-law/ [Google Scholar]

- Orr C. Eliminating intersex babies is not a legitimate use of genetic embryo testing. The Guardian. 2015 Jul 15; Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/jul/10/intersex-babies-genetic-embryo-testing.

- Pandey G. India court recognises transgender people as third gender. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-27031180.

- Phillips A. Criminal charges were just filed in Flint. But suing over the water crisis remains very difficult. The Washington Post. 2016 Apr 20; Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2016/01/26/why-it-will-be-very-difficult-for-flint-residents-to-sue-the-state-of-michigan-for-money/ [Google Scholar]

- Preves SE. Sexing the intersexed: An analysis of sociocultural responses to intersexuality. Signs. 2002;27(2):523–556. [Google Scholar]

- Preves SE. Intersex and Identity: The Contested Self. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Reis E. Divergence or disorder? The politics of naming intersex. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 2007;50(4):535–543. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2007.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders C, Carter B, Goodacre L. Parents' narratives about their experiences of their child's reconstructive genital surgeries for ambiguous genitalia. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008;17(23):3187–3195. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scobey-Thal J. Third Gender: A Short History. Foreign Policy. 2014 Retrieved from http://foreignpolicy.com/2014/06/30/third-gender-a-short-history/ [Google Scholar]

- Short SE, Mollborn S. Social determinants and health behaviors: conceptual frames and empirical advances. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2015;5:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow R. Gender Eugenics? The Ethics of PGD for Intersex Conditions. American Journal of Bioethics. 2013;13(10):29–38. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2013.828115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz K. Oxford English Dictionary Adds ’Merica, Gender-Fluid and Squee. Time Magazine. 2016 Retrieved from http://time.com/4485727/oed-merica-gender-fluid-squee-new-words/ [Google Scholar]

- Streuli JC, Vayena E, Cavicchia-Balmer Y, Huber J. Shaping Parents: Impact of Contrasting Professional Counseling on Parents' Decision Making for Children with Disorders of Sex Development. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2013;10(8):1953–1960. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer SH. Does "difficult patient" status contribute to de facto demedicalization? The case of borderline personality disorder. Social Science & Medicine. 2015;142:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uslan SS. What Parents Don't Know: Informed Consent, Marriage, and Genital-Normalizing Surgery on Intersex Children. Indiana Law Journal. 2010;85(1):301–323. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal I, Gorduza DB, Haraux E, Gay C-L, Chatelain P, Nicolino M, Mouriquand P. Surgical options in disorders of sex development (DSD) with ambiguous genitalia. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2010;24(2):311–324. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warne GL, Mann A. Ethical and legal aspects of management for disorders of sex development. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2011;47(9):661–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westenfelder M. Medical and legal aspects of treating ambiguous genitalia. Urologe. 2011;50(5):593–599. doi: 10.1007/s00120-011-2531-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiler K, Wickstrom A. Why do 'we' perform surgery on newborn intersexed children? The phenomenology of the parental experience of having a child with intersex anatomies. Feminist Theory. 2009;10(3):359–377. [Google Scholar]

- Zola IK. Medicine as an Institution of Social Control. In: Conrad P, editor. Sociology of Health and Illness. Eighth. New York: Worth Publishing; 1978 [2009]. pp. 470–480. [Google Scholar]