Abstract

Septins are GTP-binding and membrane-interacting proteins with a highly conserved domain structure involved in various cellular processes, including cytoskeleton organization, cytokinesis, and membrane dynamics. To date, 13 different septin genes have been identified in mammals (SEPT1 to SEPT12 and SEPT14), which can be classified into four distinct subgroups based on the sequence homology of their domain structure (SEPT2, SEPT3, SEPT6, and SEPT7 subgroup). The family members of these subgroups have a strong affinity for other septins and form apolar tri-, hexa-, or octameric complexes consisting of multiple septin polypeptides. The first characterized core complex is the hetero-trimer SEPT2-6-7. Within these complexes single septins can be exchanged in a subgroup-specific manner. Hexamers contain SEPT2 and SEPT6 subgroup members and SEPT7 in two copies each whereas the octamers additionally comprise two SEPT9 subgroup septins. The various isoforms seem to determine the function and regulation of the septin complex. Septins self-assemble into higher-order structures, including filaments and rings in orders, which are typical for different cell types. Misregulation of septins leads to human diseases such as neurodegenerative and bleeding disorders. In non-dividing cells such as neuronal tissue and platelets septins have been associated with exocytosis. However, many mechanistic details and roles attributed to septins are poorly understood. We describe here some important mammalian septin interactions with a special focus on the clinically relevant septin interactions.

Keywords: septins, septin-multimers, septin-interacting proteins, platelets, human endothelial cells

Introduction

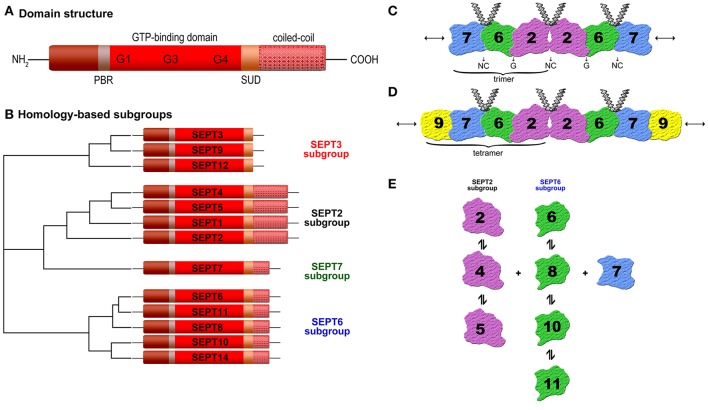

Septins (SEPTs) have been originally discovered in Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a family of proteins associated with cytokinesis and cell morphology. They received their name due to the involvement in the septum formation during yeast budding and are expressed in all eukaryotes, except in plants (Hartwell et al., 1974; Kinoshita and Noda, 2001; Pan et al., 2007). The first human septin was described in 1994 (Nakatsuru et al., 1994). To date, 13 functional septin genes encoding tissue-specific and ubiquitous expressed septins (SEPT1 to SEPT12 and SEPT14) have been identified (Kinoshita, 2003a). The number of septins varies between eukaryotic cells, from one in some algae to 13 in humans (Cao et al., 2009; Nishihama et al., 2011). Septins are an evolutionarily highly conserved protein group and belong to the Ras-like GTPase superclass of phosphate-binding loop (P-loop) NTPases (Leipe et al., 2002). All known septins (30–65 kDa) share a common structural domain organization (Figure 1A): A highly conserved central GTP-binding region, a variable amino-terminus, and a carboxyl-terminus often predicted to form coiled-coil structures, possibly involved in mediating protein-protein interactions (Trimble, 1999). Between the N-terminus and the GTPase domain, a short polybasic region (PBR) is found in most septin sequences, which binds directly to phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate (PIP2), and may be responsible for mediating interactions with plasma membranes (Casamayor and Snyder, 2003). A septin-unique domain (SUD) of unknown function exists C-terminally (Pan et al., 2007). The GTPase domain (G-domain) itself has a mixed α-helix/β-sheet secondary-structure and contains three motifs: G1 (GxxxxGK[s/T]) is characterized by the presence of the P-loop and is capable of interacting with nucleotide phosphate groups. Both G3 (DxxG) and G4 (xKxD) are directly associated with GTP binding (Sirajuddin et al., 2009). Based on their sequence homology and the number of coiled-coil domains, mammalian septins can be subdivided into four different groups termed according to their founding member SEPT2, SEPT3, SEPT6, or SEPT7 (Figure 1B). The SEPT2 subgroup (SEPT1, 2, 4, 5) contains two coiled-coil domains. The SEPT3 subgroup (SEPT3, 9, 12) has no coiled-coil domain. The SEPT6 (SEPT6, 8, 10, 11, 14) and the SEPT7 subgroup (SEPT7), respectively comprise one coiled-coil domain (Macara et al., 2002; Kinoshita, 2003b).

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic septin domain structure. Septins share a conserved GTP-binding domain, a phosphoinosite-binding polybasic region (PBR), a septin unique domain (SUD), and most of them one or more coiled-coil domains. The length and amino acid sequence of the N- and C-terminus vary (according to Trimble, 1999). (B) Homology-based subgroups. The 13 human septins (SEPT1 to SEPT12 and SEPT14) are classified into four subgroups (SEPT3, SEPT2, SEPT7, and SEPT6) based on sequence homology and coiled-coil domains (Macara et al., 2002; Kinoshita, 2003b). (C) Structure of the SEPT2-6-7 complex. Two copies of each septin are symmetrically arranged (SEPT7-6-2-2-6-7) to generate a hexamer by alternating N- and C-termini (NC) and G-interface (GTP-binding domain) (Sirajuddin et al., 2007). (D) Structure of the SEPT2-6-7-9 complex (Sandrock et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2011). (E) Binding preferences of individual septins to other septins (Sandrock et al., 2011).

Specificity of septin interactions

Unlike RAS-like GTP-binding proteins the septins can assemble into multimeric complexes including two or more subunits depending on the organism (Field et al., 1996; John et al., 2007; Sellin et al., 2011a). The classification of mammalian septins into four subgroups has relevance for the formation of these septin complexes because individual septins from each group can polymerize into a variety of higher-order structures, such as filaments, bundles, or rings (Mostowy and Cossart, 2012). Several studies have shown subgroup-restricted binding preferences of mammalian septins (Table 1) and that the typical filamentous form involves a hetero-trimer as its core module (Sirajuddin et al., 2007; Nakahira et al., 2010; Sandrock et al., 2011; Sellin et al., 2011a). Sirajuddin et al. first solved the crystal structure of the mammalian septin complex containing SEPT2, 6, and 7 and demonstrated its hexameric composition with mirroring symmetry arranged as a head-to-head trimer in the order 7-6-2-2-6-7 (Sirajuddin et al., 2007) (Figure 1C). In humans septins self-assemble predominantly into hetero-hexamers or hetero-octamers, whereas the hetero-octamers additionally contain SEPT3 subgroup members (Sellin et al., 2014). Sandrock et al. and Kim et al. showed that SEPT9 caps the ends of octameric complexes with SEPT7 (9-7-6-2-2-6-7-9) (Kim et al., 2011; Sandrock et al., 2011) (Figure 1D).

Table 1.

Subgroup-specific septin-septin binding preferences, septin-interacting proteins, and their physiological relevance.

| Septin subgroup | Preferred partner | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEPT6 group | SEPT2 group, SEPT3 group, SEPT7 group | Nakahira et al., 2010; Sandrock et al., 2011 | |

| SEPT2 group | SEPT6 group | Nakahira et al., 2010; Sandrock et al., 2011 | |

| SEPT3 group | SEPT7 group | Nakahira et al., 2010; Sandrock et al., 2011 | |

| Protein | Interacting septin | Physiological relevance | References |

| CENP | Septin 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9 | Exocytose, intracellular trafficking | Nakahira et al., 2010 |

| SNX6 | Septin 2, 5, 6, 8, 11 | Exocytose, intracellular trafficking | Nakahira et al., 2010 |

| Sec6/8 | Septin 2, 4, 6, 7 | Vesicle transport | Ihara et al., 2005 |

| Syntaxin1A | Sepin 2, 5 | Vesicle transport | Beites et al., 2001 |

| VAMP1 | Septin 4, 11 | Vesicle transport | Zhang et al., 2000 |

| Transferrin receptor | Septin 4, 11 | Vesicle transport | Zhang et al., 2000 |

| FLNA | Septin 9 | Cytoskeleton organization, vesicle transport | Nakahira et al., 2010 |

| SH3KBP1 | Septin 9 | Cytoskeleton organization, vesicle transport | Nakahira et al., 2010 |

| IFT27 | Septin 3, 7 | Vesicle transport, endocytose | Nakahira et al., 2010 |

| Ra1ABP1 | Septin 3, 7 | Vesicle transport, endocytose | Nakahira et al., 2010 |

| Actin cytoskeleton | Septins | Multiple functions | Kinoshita et al., 2002; Spiliotis et al., 2005 |

| Microtuble cytokeleton | Septins | Multiple functions | Surka et al., 2002; Nagata et al., 2003; Kremer et al., 2005; Joo et al., 2007; Bowen et al., 2011; Mostowy and Cossart, 2012 |

| Pospholipid membrane | Septins | Multiple functions | Spiliotis et al., 2008; Tanaka-Takiguchi et al., 2009 |

| Anillin | Septin 2 | Filament organization | Spiliotis et al., 2005 |

| α-Tubulin | Septin complexes | Regulation of actin and tubulin polymerization | Nagata et al., 2003 |

| Cytochalasin D | Septin 2, 6 | Regulation of actin polymerization | Spiliotis et al., 2005 |

| Latrunculin | Septin 2, 6 | Regulation of actin polymerization | Spiliotis et al., 2005 |

| MAP4 | Septin 2-6-7 complex | Modulation of microtuble dynamics | Bowen et al., 2011 |

| HDAC6 | Septin 7 | Dendritic development | Ghossoub et al., 2013 |

| ERK3 | Septin 7 | Dendritic morphology | Ageta-Ishihara et al., 2013 |

| Aurora-B | Septin 1 | Mitose, cytokinesis | Hu et al., 2012 |

| Cdk1/Pin1 | Septin 9 | Cytokinesis | Qi et al., 2005 |

| Drp1 | Septin 2 | Mitochondrial fission | Estey et al., 2013 |

| Tau, NFTs | Septin 1, 2, 4 | Neuronal differentation and growth | Pagliuso et al., 2016 |

| Parkin | Septin 5 | Regulation of neuronal differentation and growth | Takehashi et al., 2004 |

| α-Synuclein | Septin 4 | Regulation of neuronal differentation and growth | Dong et al., 2003; Ihara et al., 2003 |

| MLL | Septin 5, 6, 9, 11 | Myeloid-lymphoid leukemia | Megonigal et al., 1998; Zieger et al., 2000 |

| BORG3-cdc42 | Septin 6, 7 | Cell polarity, cytokinesis, vesicle transport | Engidawork et al., 2003; Kuo et al., 2015 |

| BORG4-AP-3 | Septin 6, 7 | Regulation of endocytose | Joberty et al., 2001; Baust et al., 2008 |

| KIF17 | Septin 9 | Intracellular protein transport | Nakahira et al., 2010; Traikov et al., 2014 |

| UBE21, SUMO, PIAS | Near all septins | Protein degradation | Nakahira et al., 2010 |

The mammalian six subunit core heteromers are apparently stable protein complexes (Sellin et al, 2011b) but several studies showed that within one septin subgroup the individual members can substitute for one of the others at the same position of the complex in vivo and in vitro (Nakahira et al., 2010; Sandrock et al., 2011). For example, SEPT2 in the SEPT2-6-7 complex is replaceable by SEPT4 or 5 (Figure 1E), SEPT6 by SEPT8, 10, or 11. Several different trimers have been described, including SEPT3-5-7 (Fujishima et al., 2007), SEPT4-5-8 (Martinez et al., 2004), SEPT5-7-11 (Xie et al., 2007), SEPT7-11-9b (Nagata et al., 2004). The subunit heteromers depend on SEPT7 for stability (Sellin et al., 2011a). Mutations of a potential phosphorylation site within SEPT7 regulates the binding to all other septins (Sandrock et al., 2011). The higher-order septin structures are assembled from a mixture of hexamers and octamers, which all include the SEPT7 and variable SEPT2, 3, and 6 subgroup members. The composition of the septin complex is cell-type specific and essential for certain functions. At the mammalian sperm annulus SEPT12 as well as SEPT9 can flank the SEPT2-6-7 hexamers to form octamers (e.g., 12-7-6-2-2-6-7-12 or 12-7-6-4-4-6-7-12), suggesting a critical role in sperm motility (Kuo et al., 2015). These interaction studies in yeast and immunoprecipitation approaches have hinted toward the existence of diverse non-canonical septin complexes, but future studies are needed to determine the factors determining heteropolymer assembly.

Septins polymerize and interact with other septins via two interaction interfaces (G- and NC-interface) (Sirajuddin et al., 2007, 2009). The G-interfaces comprise the GTP-binding domain whereas the NC-interfaces involve the N- and C-terminal regions, which are brought into close proximity upon folding (Sheffield et al., 2003). This means, each septin subunit assembles and extends apolar filaments arranged in a palindromic order by alternating NC- and G-interface associations (Figure 1C). Upon GTP-binding a conformational change in the switch regions is provoked, which affects the G- and the NC-interface. The GTP-binding capacity of septins is essential for septin-septin interactions and fundamental to ensure structural integrity, in a way that GTP-binding and its hydrolysis control assembly and disassembly of filaments and also the stability of the interface within the septin polymer (Zeraik et al., 2014). In the SEPT2-6-7 complex SEPT2 and 7 bind to GDP, while SEPT6 binds to GTP (de Almeida Marques et al., 2012). A Sept11 mutant, which showed reduced GTPase activity, was unable to form filaments (Hanai et al., 2004). Moreover, the GTPase domain seems to form homo-dimers and homo-filaments in vitro (Garcia et al., 2006; Huang et al., 2006; Nakahira et al., 2010). Studies showed that single septins may be unstable and assemble into homo-dimers or a fibrillary aggregated form called amyloid in the absence of GTP and by unbalanced stoichiometries. Depending on the temperature SEPT2 can exist as a dimer and contains regions within its G-domain sequence with a tendency to aggregate and/or form amyloids (Pissuti Damalio et al., 2012). Thereby, a decrease of α-helical content and a gain in β-sheet structure has been observed. Also homo-multimers have been reported for human SEPT2 in both the GTP- and GDP-bound states (Huang et al., 2006). Furthermore, Garcia et al. reported that SEPT4-G (an intermediate structure of the GTPase domain of human SEPT4) can form homo-filaments and amyloid-like aggregates (Garcia et al., 2007, 2008).

Due to alternative mRNA splicing many human septin genes present several variants. Cell culture models showed that the human SEPT9 exists as multiple isoforms, which have a common G-domain but differ in both length and sequence of the N-terminus. The SEPT9 isoform and expression level determine the higher-order arrangement of septin filaments (Sellin et al., 2012). In cells lacking SEPT7 mutational analysis of interaction surfaces reveals that SEPT9 exists as monomer (Kim et al., 2011; Sellin et al., 2011a). Besides the G-domain, the C-terminal domains and their coiled-coil regions are important determinants for filament assembly and stability and are important for recognition and binding of partner molecules (de Almeida Marques et al., 2012). For example, some septins interact with proteins (CENP-E/F, SNX6), which are associated with intracellular trafficking and exocytosis or are part of the kinetochore via coiled-coil domains (Nakahira et al., 2010) (Table 1). Filaments containing septins are implicated in exocytosis and are closely involved in membrane transport and fusion (Blaser et al., 2004; Ihara et al., 2005). Septins may associate to provide a targeting system to recruit secretory vesicles to appropriate docking/fusion sites leading to the correct organization of proteins along the plasma membrane. In brain lysates of rats the septins SEPT2, 4, 6, and 7 are associated with the exocyst complex sec6/8 that is essential for neuronal vesicle transport (Hsu et al., 1998). In neurons SEPT2 and 5 have been shown to interact with syntaxin 1A, a t-SNARE protein predominantly present on the plasma membrane, and they copurify with synaptic vesicles (Beites et al., 1999, 2001; Zhang et al., 2000). Bartsch et al. demonstrated the colocalization of SEPT4 and 11 with the vesicle-associated protein synaptobrevin 1 (VAMP1) and the endocytotic transferrin receptor (Bartsch et al., 2010). Moreover, SEPT9 interacts with filamin A (FLNA) and SH3-domain kinase binding protein 1 (SH3KBP1) via N-terminus (Nakahira et al., 2010), two proteins involved in cytoskeleton organization and vesicle transport (van der Flier and Sonnenberg, 2001; Spiliotis et al., 2005). Further septin partners associated with vesicle transport are other Ras-like GTPases (IFT27, Ra1ABP1) (Nakahira et al., 2010).

Mammalian septins interact with actin (Kinoshita et al., 2002; Joo et al., 2007) and microtubule cytoskeletons (Surka et al., 2002; Nagata et al., 2003; Kremer et al., 2005; Spiliotis et al., 2008; Bowen et al., 2011; Sellin et al, 2011b), as well as with phospholipid membranes (Tanaka-Takiguchi et al., 2009; Bertin et al., 2010). Thus, they assemble at specific locations in the cell to coordinate changes in membrane and cytoskeletal organization by acting as cell scaffolds for protein recruitment to specific sites in a cell and/or as lateral diffusion barriers in the plasma membrane to compartmentalize discrete cellular domains. Unlike actin and microtubules, septin complexes are apolar along the longitudinal axis in recombinant systems. One important actin-binding protein, which interacts with septins at the cell surface is anillin (Kinoshita et al., 2002). Anillin mediates the septin filament organization along actin bundles by recruiting and stabilizing myosin, actin, and regulatory kinases (Joo et al., 2007; Maddox et al., 2007). Septin complexes interact with α-tubulin and control actin and tubulin polymers (Surka et al., 2002). In fibroblasts cytochalasin D or latrunculin inhibit the actin polymerization and the septin filaments disappear while septin rings occur, which are not associated with actin (Kinoshita et al., 2002). The microtubule-associated protein MAP4, which is required for modulation of microtubule dynamics during mitosis and cytokinesis, is another septin binding partner. MAP4 is recruited to the SEPT2-6-7 complex via the direct interaction of its C-terminal proline-rich domain with SEPT2 (Kremer et al., 2005). SEPT2 together with MAP4 is involved in the organization of primary cilia (Ghossoub et al., 2013). In addition, SEPT7 is associated with transport of organelles and regulates dendritic morphology (Xie et al., 2007) by interaction with α-tubulin deacetylase HDAC6 (Ageta-Ishihara et al., 2013) or extracellular signal-regulated kinase 3 (ERK3) (Brand et al., 2012). In developing axon collateral branches, SEPT7 influences the remodeling of microtubules into filopodia, a process required for successful formation of branches (Hu et al., 2012). Tubulin-associated SEPT2 facilitates vesicle transport from the Golgi to the plasma membrane (Spiliotis et al., 2008). Furthermore, septins are involved in cell division. SEPT1 is a target of aurora-B, which is an important serine/threonine kinase required for chromosome segregation and cytokinesis (Qi et al., 2005). Phosphorylation of SEPT9 by cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1) regulates association with the proline isomerase (Pin1), which is crucial for the disjunction of daughter cells (Estey et al., 2013).

Recently SEPT2 has been shown to participate in dynamin-like protein Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission (Pagliuso et al., 2016). Misregulation of human septins is associated with numerous diseases, like neurodegenerative disorders. For example, septins are involved in Alzheimer's disease (AD) because they interact with neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). SEPT1, 2 and 4 bind the microtubule-associated protein tau, a major component of the neurofibrillary tangles, which is important for neuronal differentiation and growth (Kinoshita et al., 1998). Furthermore, genotype studies of polymorphic SEPT3 alleles in human neuronal cells indicated a significant difference between AD patients and controls (Takehashi et al., 2004). Another binding partner of septins is parkin, which is mutated in autosomal-recessive juvenile parkinsonism (ARJP) (Kitada et al., 1998). Parkin, an ubiquitin ligase, interacts with SEPT5 and mediates its degeneration (Choi et al., 2003; Son et al., 2005). A loss of parkin causes accumulation of SEPT5 in neurons of patients with ARJP and induces selective dopamine-dependent neurodegeneration. SEPT5 inhibits the release of dopamine (Zhang et al., 2000; Choi et al., 2003; Dong et al., 2003; Son et al., 2005). In Parkinson‘s disease or dementia SEPT4 is accumulated in cytoplasmic aggregates colocalizing with the dopamine receptor α-synuclein. Sept4 deficient mice exhibit diminished dopaminergic neurotransmission due to the lack of SEPT4 (Ihara et al., 2003, 2005, 2007). SEPT4 is a distinct gene product with a >90% identity to SEPT5 (Zieger et al., 2000). Some human septin proteins (SEPT5, 6, 9, and 11) have been cloned as fusion partner of myeloid-lymphoid leukemia MLL (also referred to as ALL1 or HRX) genes. These fusion proteins consist of almost the entire open reading frame of the involved septin and the N-terminus of MLL (Megonigal et al., 1998; Kojima et al., 2004). Thus, misregulation of human septins plays a role in cancer. SEPT9 supports HIF-1α-mediated transcription in tumor cells (Amir et al., 2009), suggesting that SEPT9 is a player in posttranslational modification. Down-syndrome patients showed an increased expression of mixed lineage leukemia septin like fusion protein (MSF)-B, suggesting a hint why Down-syndrome children show a stringent incidence of acute leukemia (Engidawork et al., 2003).

Septins have been shown to interact with BORGs (binding partners of RHO-GTPases; CDC42 effector proteins). For example, BORG3 binds directly to SEPT6 or 7 (Joberty et al., 2001; Sheffield et al., 2003). BORGs (BORG1 to BORG3) interact generally with two types of GTPases, namely septins and CDC42. Overexpression of constitutively active CDC42-GTPase markedly affects the association of BORG3 with septins and disrupts normal septin complex organization leading to a pathological localization of the septins within the cell. Thus, BORGs are important regulators of mammalian septin organization and provide a link between the septins and CDC42-GTPases, which regulate cell polarity, cytokinesis, cytoskeletal remodeling and vesicle transport (Joberty et al., 2001). Baust et al. identified a septin-/BORG-protein network und hypothesized that BORG4 and septins are important regulators for the AP-3 adaptor complex-dependent sorting of the lysosome membrane protein 1 (LAMP-1) to lysosomes (Baust et al., 2008). AP-3 is a member of an adaptor complex, which is involved in the targeting of cargo destined to remain in outer membranes of maturing endosomal compartments. In this complex, SEPT6 and 7 function as regulators of endosome transport by modulating the timely coordinated interaction of AP-3 (Traikov et al., 2014). In addition, SEPT9 interacts with the kinesin 2 family motor KIF17, which is a cargo/scaffold protein, suggesting the importance of SEPT9 in transport mechanisms in neurons (Bai et al., 2016). SEPT9 also regulates growth and accumulation of lipid droplets, which are frequently observed in hepatitis C virus infection (HCV), by a phosphatidylinositol-5-phosphate and microtubule-dependent binding mechanism in HCV-infected cells (Akil et al., 2016).

Nakahira et al. described septin interactions with several proteins that play a role in protein degeneration and functionally associated with the ubiquitin and sumoylation cycles (e.g., UBE21, SUMO, or PIAS) (Nakahira et al., 2010). Sumoylation generally controls assembly, localization, stability and other functions of protein complexes (Schmidt and Muller, 2003; Johnson, 2004).

Septin interactions in platelets and human endothelial cells

In platelets several septins (SEPT2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, and 11) are expressed, which seem to be important for regulating platelet function (Yagi et al., 1998; Zieger et al., 2000; Blaser et al., 2003; Bartsch et al., 2010; Sandrock et al., 2011). Transmission electron microscopy revealed that SEPT4 and 8 surround the α-granules, as it had been shown for SEPT5, suggesting that they may be components of the same complex in platelets and play in such a way a general regulatory role in platelet biology. Activation of platelets by agonists resulted in the translocation of SEPT4 and 8 to the platelet surface indicating a possible functional role of these proteins in platelet granular transport and secretion (Dent et al., 2002; Blaser et al., 2004; Martinez et al., 2006). Platelets from Sept5 deficient mice showed altered granule release (serotonin) and revealed a decreased threshold for agonist-mediated platelet aggregation, suggesting that SEPT5 is involved in platelet physiology (Dent et al., 2002). Sept5 deficient mice presented a marked increase in bleeding symptoms compared to wild-type mice. The regulatory factors promoting vesicle docking and fusion after platelet stimulation are unknown so far, but it might be a large multimeric complex of various proteins involved in platelet biology. The interaction in a macromolecular complex in platelets between SEPT5 and syntaxin-4, which is involved in vesicle transport, suggests a cooperation of these proteins supporting the critical role of SEPT5 in granule secretion. Interestingly, in platelets SEPT5 has a strong affinity for other septins, such as SEPT4 and 8, which are expressed together in various tissues (Blaser et al., 2002; Martinez et al., 2004). In addition, SEPT5 has been shown to be colocalized with SEPT6 in the periphery of the platelet and in the cytoplasma and was associated with platelet microtubules in the SEPT5-6-7 complex promoting the important role of septins in granule trafficking through their association with the microtubule network. Martinez et al. revealed furthermore that SEPT9 is part of the SEPT5-6-7-9 complex in platelets (Martinez et al., 2006). In platelets and HUVECs, SEPT5 has been identified as an interaction partner of SEPT11, which may also be involved in regulated secretion (Blaser et al., 2006). Many septins are expressed ubiquitously, for example SEPT6 (Ono et al., 2002), SEPT7, 9, and 11 (Hanai et al., 2004) while a subset appears tissue restricted (Hall et al., 2005; Cao et al., 2007), like SEPT5 (previous: hCDCrel-1; human cell division cycle gene, PNUTL1) (Macara et al., 2002), which is expressed predominantly in platelets, brain, and heart (McKie et al., 1997; Yagi et al., 1998). In addition, SEPT5 deficiency exerts pleiotropic effects on affective behaviors and cognitive functions as shown in Sept5 knock-out mice, which feature delayed acquisition of rewarded goal approach (Suzuki et al., 2009). In HIT-T15 cells mutations in SEPT5 inside the GTP-binding domain lead to an increased granule secretion (Beites et al., 1999). As shown before, in human endothelial cells SEPT4 and 11 are involved in endo- and exocytotic processes by interacting with vesicle-associated proteins (Bartsch et al., 2010). These studies confirm the binding preferences of the SEPT2 subgroup (SEPT4 and 5) with members of the SEPT6 subgroup (SEPT8 and 11) (Figure 1E).

Interestingly, mice with Bernard-Soulier-syndrome (BBS) caused by genetic deletion of the platelet glycoprotein (GP) Ibβ (GP1BB) demonstrated increased levels of SEPT5 in the megakaryocytic linage. Overexpression of SEPT5 is associated with fewer and larger platelet α-granules, suggesting that SEPT5 supports normal α-granule size in wild-type littermates (Kato et al., 2004). SEPT5 was identified as a 5′gene located in close 5′proximity to the GPIbβ gene (Zieger et al., 1997). GPIbβ is besides GPIbα a subunit of GPIb, which is a major component of the platelet membrane receptor (GPIb/IX) for von Willebrand factor (Ruggeri, 1991). Both genes, SEPT5 and GPIbβ, are located within the chromosomal locus 22q11.2, a region associated with the DiGeorge syndrome (DGS) and other cardio-facial abnormalities (McDermid and Morrow, 2002). The close relationship of DGS and GPIbβ has been confirmed by chromosomal deletion of 22q11.2 in a patient with both DGS and BSS (congenital absence of the platelet GPIb/V/IX receptor complex) (Budarf et al, 1995).

In a boy with a unique homozygous deletion of the two contiguous genes SEPT5 and GPIbβ resulted in a BSS phenotype (reduced expression of the GPIb/V/IX receptor) combined with a platelet secretion defect (Bartsch et al., 2011). The patient suffered from life-threatening bleedings, which could be hardly stopped. Therefore, he received hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Because of the deletion of SEPT5 (which is also important for vesicle transport and exocytosis in neurons) the patient showed an additional secretion defect of platelet α-granules. Most probably, the platelet secretion defect resulted in an additive effect regarding his bleeding symptoms besides the BSS defect. Furthermore, the patient is retarded in development and shows autistic streaks. The cortical dysplasia (polymicrogyry) and neurologic dysfunction is likely caused by the SEPT5 deletion. His parents both exhibit a heterozygous deletion on this area.

Conclusion

Diverse studies showed cell-specific formation of mammalian septin-multimers and their association with a variety of the cellular processes, such as actin dynamics, microtubule regulation, membrane trafficking, vesicle transport, exocytosis, the assembly of scaffolding platforms, protein degradation, and mechanical stability. Many septins have been associated with diverse human diseases, such as neurodegenerative and bleeding disorders. Homozygous deletion of ubiquitary septins results in embryonic lethality (Roseler et al., 2011). Exact structural properties and many of the molecular details and modes of action remain unclear. The complex relationship between polymerization, bundling, GTPase activity and membrane association needs to be elucidated in future studies.

Author contributions

All authors listed, have made substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (ZI 486/4-1).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Ageta-Ishihara N., Miyata T., Ohshima C., Watanabe M., Sato Y., Hamamura Y., et al. (2013). Septins promote dendrite and axon development by negatively regulating microtubule stability via HDAC6-mediated deacetylation. Nat. Commun. 4:2532. 10.1038/ncomms3532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akil A., Peng J., Omrane M., Gondeau C., Desterke C., Marin M., et al. (2016). Septin 9 induces lipid droplets growth by a phosphatidylinositol-5-phosphate and microtubule-dependent mechanism hijacked by HCV. Nat. Commun. 7:12203. 10.1038/ncomms12203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir S., Wang R., Simons J. W., Mabjeesh N. J. (2009). SEPT9_v1 up-regulates hypoxia-inducible factor 1 by preventing its RACK1-mediated degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 11142–11151. 10.1074/jbc.M808348200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai X., Karasmanis E. P., Spiliotis E. T. (2016). Septin 9 interacts with kinesin KIF17 and interferes with the mechanism of NMDA receptor cargo binding and transport. Mol. Biol. Cell 27, 897–906. 10.1091/mbc.E15-07-0493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch I., Blaser S., Roseler S., Sandrock K., Busse A., Huber M., et al. (2010). Human endothelial and platelet septin SEPT11: cloning of novel variants and characterisation of interaction partners. Thromb. Haemost. 104, 1201–1210. 10.1160/TH10-07-0472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch I., Sandrock K., Lanza F., Nurden P., Hainmann I., Pavlova A., et al. (2011). Deletion of human GP1BB and SEPT5 is associated with Bernard-Soulier syndrome, platelet secretion defect, polymicrogyria, and developmental delay. Thromb. Haemost. 106, 475–483. 10.1160/TH11-05-0305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baust T., Anitei M., Czupalla C., Parshyna I., Bourel L., Thiele C., et al. (2008). Protein networks supporting AP-3 function in targeting lysosomal membrane proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 1942–1951. 10.1091/mbc.E08-02-0110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beites C. L., Peng X. R., Trimble W. S. (2001). Expression and analysis of properties of septin CDCrel-1 in exocytosis. Methods Enzymol. 329, 499–510. 10.1016/S0076-6879(01)29111-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beites C. L., Xie H., Bowser R., Trimble W. S. (1999). The septin CDCrel-1 binds syntaxin and inhibits exocytosis. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 434–439. 10.1038/8100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertin A., McMurray M. A., Thai L., Garcia G., III, Votin V., Grob P., et al. (2010). Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate promotes budding yeast septin filament assembly and organization. J. Mol. Biol. 404, 711–731. 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaser S., Horn J., Wurmell P., Bauer H., Strumpell S., Nurden P., et al. (2004). The novel human platelet septin SEPT8 is an interaction partner of SEPT4. Thromb. Haemost. 91, 959–966. 10.1160/th03-09-0578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaser S., Jersch K., Hainmann I., Wunderle D., Zgaga-Griesz A., Busse A., et al. (2002). Human septin-septin interaction: CDCrel-1 partners with KIAA0202. FEBS Lett. 519, 169–172. 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)02749-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaser S., Jersch K., Hainmann I., Zieger W., Wunderle D., Busse A., et al. (2003). Isolation of new splice isoforms, characterization and expression analysis of the human septin SEPT8 (KIAA0202). Gene 312, 313–320. 10.1016/S0378-1119(03)00635-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaser S., Roseler S., Rempp H., Bartsch I., Bauer H., Lieber M., et al. (2006). Human endothelial cell septins: SEPT11 is an interaction partner of SEPT5. J. Pathol. 210, 103–110. 10.1002/path.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen J. R., Hwang D., Bai X., Roy D., Spiliotis E. T. (2011). Septin GTPases spatially guide microtubule organization and plus end dynamics in polarizing epithelia. J. Cell Biol. 194, 187–197. 10.1083/jcb.201102076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand F., Schumacher S., Kant S., Menon M. B., Simon R., Turgeon B., et al. (2012). The extracellular signal-regulated kinase 3 (mitogen-activated protein kinase 6 [MAPK6])-MAPK-activated protein kinase 5 signaling complex regulates septin function and dendrite morphology. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32, 2467–2478. 10.1128/MCB.06633-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budarf M. L., Konkle B. A., Ludlow L. B., Michaud D., Li M., Yamashiro D. J., et al. (1995). Identification of a patient with Bernard-Soulier syndrome and a deletion in the DiGeorge/velo-cardio-facial chromosomal region in 22q11.2. Hum. Mol. Genet. 4, 763–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L., Ding X., Yu W., Yang X., Shen S., Yu L. (2007). Phylogenetic and evolutionary analysis of the septin protein family in metazoan. FEBS Lett. 581, 5526–5532. 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.10.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L., Yu W., Wu Y., Yu L. (2009). The evolution, complex structures and function of septin proteins. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 66, 3309–3323. 10.1007/s00018-009-0087-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casamayor A., Snyder M. (2003). Molecular dissection of a yeast septin: distinct domains are required for septin interaction, localization, and function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 2762–2777. 10.1128/MCB.23.8.2762-2777.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi P., Snyder H., Petrucelli L., Theisler C., Chong M., Zhang Y., et al. (2003). SEPT5_v2 is a parkin-binding protein. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 117, 179–189. 10.1016/S0169-328X(03)00318-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida Marques I., Valadares N. F., Garcia W., Damalio J. C., Macedo J. N., de Araujo A. P., et al. (2012). Septin C-terminal domain interactions: implications for filament stability and assembly. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 62, 317–328. 10.1007/s12013-011-9307-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent J., Kato K., Peng X. R., Martinez C., Cattaneo M., Poujol C., et al. (2002). A prototypic platelet septin and its participation in secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S. A. 99, 3064–3069. 10.1073/pnas.052715199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z., Ferger B., Paterna J. C., Vogel D., Furler S., Osinde M., et al. (2003). Dopamine-dependent neurodegeneration in rats induced by viral vector-mediated overexpression of the parkin target protein, CDCrel-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 12438–12443. 10.1073/pnas.2132992100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engidawork E., Gulesserian T., Fountoulakis M., Lubec G. (2003). Aberrant protein expression in cerebral cortex of fetus with Down syndrome. Neuroscience 122, 145–154. 10.1016/S0306-4522(03)00605-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estey M. P., Di Ciano-Oliveira C., Froese C. D., Fung K. Y., Steels J. D., Litchfield D. W., et al. (2013). Mitotic regulation of SEPT9 protein by cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1) and Pin1 protein is important for the completion of cytokinesis. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 30075–30086. 10.1074/jbc.M113.474932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field C. M., al-Awar O., Rosenblatt J., Wong M. L., Alberts B., Mitchison T. J. (1996). A purified Drosophila septin complex forms filaments and exhibits GTPase activity. J. Cell Biol. 133, 605–616. 10.1083/jcb.133.3.605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujishima K., Kiyonari H., Kurisu J., Hirano T., Kengaku M. (2007). Targeted disruption of Sept3, a heteromeric assembly partner of Sept5 and Sept7 in axons, has no effect on developing CNS neurons. J. Neurochem. 102, 77–92. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04478.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia W., de Araujo A. P., Lara F., Foguel D., Tanaka M., Tanaka T., et al. (2007). An intermediate structure in the thermal unfolding of the GTPase domain of human septin 4 (SEPT4/Bradeion-beta) forms amyloid-like filaments in vitro. Biochemistry 46, 11101–11109. 10.1021/bi700702w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia W., de Araujo A. P., Neto Mde O., Ballestero M. R., Polikarpov I., Tanaka M., et al. (2006). Dissection of a human septin: definition and characterization of distinct domains within human SEPT4. Biochemistry 45, 13918–13931. 10.1021/bi061549z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia W., Rodrigues N. C., de Oliveira Neto M., de Araujo A. P., Polikarpov I., Tanaka M., et al. (2008) The stability aggregation properties of the GTPase domain from human SEPT4. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1784, 1720–1727. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghossoub R., Hu Q., Failler M., Rouyez M. C., Spitzbarth B., Mostowy S., et al. (2013). Septins 2, 7 and 9 and MAP4 colocalize along the axoneme in the primary cilium and control ciliary length. J. Cell Sci. 126(Pt 12), 2583–2594. 10.1242/jcs.111377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall P. A., Jung K., Hillan K. J., Russell S. E. (2005). Expression profiling the human septin gene family. J. Pathol. 206, 269–278. 10.1002/path.1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanai N., Nagata K., Kawajiri A., Shiromizu T., Saitoh N., Hasegawa Y., et al. (2004). Biochemical and cell biological characterization of a mammalian septin, Sept11. FEBS Lett. 568, 83–88. 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell L. H., Culotti J., Pringle J. R., Reid B. J. (1974). Genetic control of the cell division cycle in yeast. Science 183, 46–51. 10.1126/science.183.4120.46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu S. C., Hazuka C. D., Roth R., Foletti D. L., Heuser J., Scheller R. H. (1998). Subunit composition, protein interactions, and structures of the mammalian brain sec6/8 complex and septin filaments. Neuron 20, 1111–1122. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80493-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J., Bai X., Bowen J. R., Dolat L., Korobova F., Yu W., et al. (2012). Septin-driven coordination of actin and microtubule remodeling regulates the collateral branching of axons. Curr. Biol. 22, 1109–1115. 10.1016/j.cub.2012.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. W., Surka M. C., Reynaud D., Pace-Asciak C., Trimble W. S. (2006). GTP binding and hydrolysis kinetics of human septin 2. FEBS J. 273, 3248–3260. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05333.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihara M., Kinoshita A., Yamada S., Tanaka H., Tanigaki A., Kitano A., et al. (2005). Cortical organization by the septin cytoskeleton is essential for structural and mechanical integrity of mammalian spermatozoa. Dev. Cell 8, 343–352. 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihara M., Tomimoto H., Kitayama H., Morioka Y., Akiguchi I., Shibasaki H., et al. (2003). Association of the cytoskeletal GTP-binding protein Sept4/H5 with cytoplasmic inclusions found in Parkinson's disease and other synucleinopathies. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 24095–24102. 10.1074/jbc.M301352200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihara M., Yamasaki N., Hagiwara A., Tanigaki A., Kitano A., Hikawa R., et al. (2007). Sept4, a component of presynaptic scaffold and Lewy bodies, is required for the suppression of alpha-synuclein neurotoxicity. Neuron 53, 519–533. 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joberty G., Perlungher R. R., Sheffield P. J., Kinoshita M., Noda M., Haystead T., et al. (2001). Borg proteins control septin organization and are negatively regulated by Cdc42. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 861–866. 10.1038/ncb1001-861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John C. M., Hite R. K., Weirich C. S., Fitzgerald D. J., Jawhari H., Faty M., et al. (2007). The Caenorhabditis elegans septin complex is nonpolar. EMBO J. 26, 3296–3307. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E. S. (2004). Protein modification by SUMO. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 355–382. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo E., Surka M. C., Trimble W. S. (2007). Mammalian SEPT2 is required for scaffolding nonmuscle myosin II and its kinases. Dev. Cell 13, 677–690. 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K., Martinez C., Russell S., Nurden P., Nurden A., Fiering S., et al. (2004). Genetic deletion of mouse platelet glycoprotein Ibbeta produces a Bernard-Soulier phenotype with increased alpha-granule size. Blood 104, 2339–2344. 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. S., Froese C. D., Estey M. P., Trimble W. S. (2011). SEPT9 occupies the terminal positions in septin octamers and mediates polymerization-dependent functions in abscission. J. Cell Biol. 195, 815–826. 10.1083/jcb.201106131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita A., Kinoshita M., Akiyama H., Tomimoto H., Akiguchi I., Kumar S., et al. (1998). Identification of septins in neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer's disease. Am. J. Pathol. 153, 1551–1560. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65743-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita M. (2003a). Assembly of mammalian septins. J. Biochem. 134, 491–496. 10.1093/jb/mvg182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita M. (2003b). The septins. Genome Biol. 4:236. 10.1186/gb-2003-4-11-236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita M., Noda M. (2001). Roles of septins in the mammalian cytokinesis machinery. Cell. Struct. Funct. 26, 667–670. 10.1247/csf.26.667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita M., Field C. M., Coughlin M. L., Straight A. F., Mitchison T. J. (2002). Self- and actin-templated assembly of Mammalian septins. Dev.Cell 3, 791–802. 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00366-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitada T., Asakawa S., Hattori N., Matsumine H., Yamamura Y., Minoshima S., et al. (1998). Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature 392, 605–608. 10.1038/33416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima K., Sakai I., Hasegawa A., Niiya H., Azuma T., Matsuo Y., et al. (2004). FLJ10849, a septin family gene, fuses MLL in a novel leukemia cell line CNLBC1 derived from chronic neutrophilic leukemia in transformation with t(4;11)(q21;q23). Leukemia 18, 998–1005. 10.1038/sj.leu.2403334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer B. E., Haystead T., Macara I. G. (2005). Mammalian septins regulate microtubule stability through interaction with the microtubule-binding protein MAP4. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 4648–4659. 10.1091/mbc.E05-03-0267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo Y. C., Shen Y. R., Chen H. I., Lin Y. H., Wang Y. Y., Chen Y. R., et al. (2015). SEPT12 orchestrates the formation of mammalian sperm annulus by organizing core octameric complexes with other SEPT proteins. J. Cell Sci. 128, 923–934. 10.1242/jcs.158998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leipe D. D., Wolf Y. I., Koonin E. V., Aravind L. (2002). Classification and evolution of P-loop GTPases and related ATPases. J. Mol. Biol. 317, 41–72. 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macara I. G., Baldarelli R., Field C. M., Glotzer M., Hayashi Y., Hsu S. C., et al. (2002). Mammalian septins nomenclature. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 4111–4113. 10.1091/mbc.E02-07-0438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox A. S., Lewellyn L., Desai A., Oegema K. (2007). Anillin and the septins promote asymmetric ingression of the cytokinetic furrow. Dev. Cell 12, 827–835. 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez C., Corral J., Dent J. A., Sesma L., Vicente V., Ware J. (2006). Platelet septin complexes form rings and associate with the microtubular network. J. Thromb. Haemost. 4, 1388–1395. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01952.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez C., Sanjuan M. A., Dent J. A., Karlsson L., Ware J. (2004). Human septin-septin interactions as a prerequisite for targeting septin complexes in the cytosol. Biochem. J. 382(Pt 3), 783–791. 10.1042/BJ20040372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermid H. E., Morrow B. E. (2002). Genomic disorders on 22q11. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 70, 1077–1088. 10.1086/340363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKie J. M., Sutherland H. F., Harvey E., Kim U. J., Scambler P. J. (1997). A human gene similar to Drosophila melanogaster peanut maps to the DiGeorge syndrome region of 22q11. Hum. Genet. 101, 6–12. 10.1007/s004390050576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megonigal M. D., Rappaport E. F., Jones D. H., Williams T. M., Lovett B. D., Kelly K. M., et al. (1998). t(11;22)(q23;q11.2) In acute myeloid leukemia of infant twins fuses MLL with hCDCrel, a cell division cycle gene in the genomic region of deletion in DiGeorge and velocardiofacial syndromes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 6413–6418. 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostowy S., Cossart P. (2012). Septins: the fourth component of the cytoskeleton. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 183–194. 10.1038/nrm3284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata K., Asano T., Nozawa Y., Inagaki M. (2004). Biochemical and cell biological analyses of a mammalian septin complex, Sept7/9b/11. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 55895–55904. 10.1074/jbc.M406153200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata K., Kawajiri A., Matsui S., Takagishi M., Shiromizu T., Saitoh N., et al. (2003). Filament formation of MSF-A, a mammalian septin, in human mammary epithelial cells depends on interactions with microtubules. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 18538–18543. 10.1074/jbc.M205246200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahira M., Macedo J. N., Seraphim T. V., Cavalcante N., Souza T. A., Damalio J. C., et al. (2010). A draft of the human septin interactome. PLoS ONE 5:e13799. 10.1371/journal.pone.0013799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsuru S., Sudo K., Nakamura Y. (1994). Molecular cloning of a novel human cDNA homologous to CDC10 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 202, 82–87. 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishihama R., Onishi M., Pringle J. R. (2011). New insights into the phylogenetic distribution and evolutionary origins of the septins. Biol. Chem. 392, 681–687. 10.1515/BC.2011.086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono R., Taki T., Taketani T., Kawaguchi H., Taniwaki M., Okamura T., et al. (2002). SEPTIN6, a human homologue to mouse Septin6, is fused to MLL in infant acute myeloid leukemia with complex chromosomal abnormalities involving 11q23 and Xq24. Cancer Res. 62, 333–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliuso A., Tham T. N., Stevens J. K., Lagache T., Persson R., Salles A., et al. (2016). A role for septin 2 in Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission. EMBO Rep. 17, 858–873. 10.15252/embr.201541612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan F., Malmberg R. L., Momany M. (2007). Analysis of septins across kingdoms reveals orthology and new motifs. BMC Evol. Biol. 7:103. 10.1186/1471-2148-7-103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pissuti Damalio J. C., Garcia W., Alves Macedo J. N., de Almeida Marques I., Andreu J. M., Giraldo R., et al. (2012). Self assembly of human septin 2 into amyloid filaments. Biochimie 94, 628–636. 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi M., Yu W., Liu S., Jia H., Tang L., Shen M., et al. (2005). Septin1, a new interaction partner for human serine/threonine kinase aurora-B. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 336, 994–1000. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roseler S., Sandrock K., Bartsch I., Busse A., Omran H., Loges N. T., et al. (2011). Lethal phenotype of mice carrying a Sept11 null mutation. Biol. Chem. 392, 779–781. 10.1515/BC.2011.093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggeri Z. M. (1991). The platelet glycoprotein Ib-IX complex. Prog. Hemost. Thromb. 10, 35–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandrock K., Bartsch I., Blaser S., Busse A., Busse E., Zieger B. (2011). Characterization of human septin interactions. Biol. Chem. 392, 751–761. 10.1515/BC.2011.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt D., Muller S. (2003). PIAS/SUMO: new partners in transcriptional regulation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 60, 2561–2574. 10.1007/s00018-003-3129-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellin M. E., Holmfeldt P., Stenmark S., Gullberg M. (2011b). Microtubules support a disk-like septin arrangement at the plasma membrane of mammalian cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 4588–4601. 10.1091/mbc.E11-09-0754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellin M. E., Sandblad L., Stenmark S., Gullberg M. (2011a). Deciphering the rules governing assembly order of mammalian septin complexes. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 3152–3164. 10.1091/mbc.E11-03-0253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellin M. E., Stenmark S., Gullberg M. (2012). Mammalian SEPT9 isoforms direct microtubule-dependent arrangements of septin core heteromers. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 4242–4255. 10.1091/mbc.E12-06-0486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellin M. E., Stenmark S., Gullberg M. (2014). Cell type-specific expression of SEPT3-homology subgroup members controls the subunit number of heteromeric septin complexes. Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 1594–1607. 10.1091/mbc.E13-09-0553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffield P. J., Oliver C. J., Kremer B. E., Sheng S., Shao Z., Macara I. G. (2003). Borg/septin interactions and the assembly of mammalian septin heterodimers, trimers, and filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 3483–3488. 10.1074/jbc.M209701200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirajuddin M., Farkasovsky M., Hauer F., Kuhlmann D., Macara I. G., Weyand M., et al. (2007). Structural insight into filament formation by mammalian septins. Nature 449, 311–315. 10.1038/nature06052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirajuddin M., Farkasovsky M., Zent E., Wittinghofer A. (2009). GTP-induced conformational changes in septins and implications for function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 16592–16597. 10.1073/pnas.0902858106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son J. H., Kawamata H., Yoo M. S., Kim D. J., Lee Y. K., Kim S., et al. (2005). Neurotoxicity and behavioral deficits associated with Septin 5 accumulation in dopaminergic neurons. J. Neurochem. 94, 1040–1053. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03257.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiliotis E. T., Hunt S. J., Hu Q., Kinoshita M., Nelson W. J. (2008). Epithelial polarity requires septin coupling of vesicle transport to polyglutamylated microtubules. J. Cell Biol. 180, 295–303. 10.1083/jcb.200710039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiliotis E. T., Kinoshita M., Nelson W. J. (2005). A mitotic septin scaffold required for Mammalian chromosome congression and segregation. Science 307, 1781–1785. 10.1126/science.1106823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surka M. C., Tsang C. W., Trimble W. S. (2002). The mammalian septin MSF localizes with microtubules and is required for completion of cytokinesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 3532–3545. 10.1091/mbc.E02-01-0042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki G., Harper K. M., Hiramoto T., Sawamura T., Lee M., Kang G., et al. (2009). Sept5 deficiency exerts pleiotropic influence on affective behaviors and cognitive functions in mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 1652–1660. 10.1093/hmg/ddp086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takehashi M., Alioto T., Stedeford T., Persad A. S., Banasik M., Masliah E., et al. (2004). Septin 3 gene polymorphism in Alzheimer's disease. Gene Express. 11, 263–270. 10.3727/000000003783992243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka-Takiguchi Y., Kinoshita M., Takiguchi K. (2009). Septin-mediated uniform bracing of phospholipid membranes. Curr. Biol. 19, 140–145. 10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traikov S., Stange C., Wassmer T., Paul-Gilloteaux P., Salamero J., Raposo G., et al. (2014). Septin6 and Septin7 GTP binding proteins regulate AP-3- and ESCRT-dependent multivesicular body biogenesis. PLoS ONE 9:e109372. 10.1371/journal.pone.0109372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimble W. S. (1999). Septins: a highly conserved family of membrane-associated GTPases with functions in cell division and beyond. J. Membr. Biol. 169, 75–81. 10.1007/s002329900519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Flier A., Sonnenberg A. (2001). Structural and functional aspects of filamins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1538, 99–117. 10.1016/S0167-4889(01)00072-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y., Vessey J. P., Konecna A., Dahm R., Macchi P., Kiebler M. A. (2007). The GTP-binding protein Septin 7 is critical for dendrite branching and dendritic-spine morphology. Curr. Biol. 17, 1746–1751. 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi M., Zieger B., Roth G. J., Ware J. (1998). Structure and expression of the human septin gene HCDCREL-1. Gene 212, 229–236. 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00146-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeraik A. E., Pereira H. M., Santos Y. V., Brandao-Neto J., Spoerner M., Santos M. S., et al. (2014). Crystal structure of a Schistosoma mansoni septin reveals the phenomenon of strand slippage in septins dependent on the nature of the bound nucleotide. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 7799–7811. 10.1074/jbc.M113.525352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Gao J., Chung K. K., Huang H., Dawson V. L., Dawson T. M. (2000). Parkin functions as an E2-dependent ubiquitin- protein ligase and promotes the degradation of the synaptic vesicle-associated protein, CDCrel-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 13354–13359. 10.1073/pnas.240347797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zieger B., Hashimoto Y., Ware J. (1997). Alternative expression of platelet glycoprotein Ib(beta) mRNA from an adjacent 5′ gene with an imperfect polyadenylation signal sequence. J. Clin. Invest. 99, 520–525. 10.1172/JCI119188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zieger B., Tran H., Hainmann I., Wunderle D., Zgaga-Griesz A., Blaser S., et al. (2000). Characterization and expression analysis of two human septin genes, PNUTL1 and PNUTL2. Gene 261, 197–203. 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00527-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]