Abstract

Objectives

The prognostic value of lactate in the setting of an emergency department (ED) has not been studied extensively. The goal of this study was to assess 28-day mortality in ED patients in whom lactate was elevated (≥4.0 mmol/L), <4.0 mmol/L or not determined and to study the impact of the underlying cause of hyperlactatemia, that is, type A (tissue hypoxia) or type B (non-hypoxia), on mortality.

Design

Retrospective study.

Setting

A secondary and tertiary referral centre in the Netherlands.

Materials and methods

All internal medicine patients with hyperlactatemia (≥4.0 mmol/L) at the ED between January 2011 and October 2014 were included in this study. Samples of patients with lactate levels <4.0 mmol/L and of patients in whom no lactate was measured were included as a reference.

Results

In 1144 of 19 822 patients (5.8%), lactate was measured. Hyperlactatemia (n=197) was associated with a higher 28-day mortality than in those with lactate <4.0 mmol/L (40.6% vs 18.5%; p<0.001) and in those without lactate measurements (9.5%). Type A hyperlactatemia, present in 84% of those with hyperlactatemia, was associated with higher mortality than type B hyperlactatemia (45.8% vs 12.5%, p=0.001).

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the prognostic value of lactate depends largely on the underlying cause and the population in whom lactate has been measured. Prospective studies are required to address the true added value of lactate at the ED.

Keywords: Hyperlactatemia; Mortality; Prognostic value; Emergency service, hospital

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to include a control group of patients in whom no lactate was measured and is therefore the first to take selection bias into account.

This study is the first to study the difference in outcome for type A and B hyperlactatemia separately.

The differentiation between type A and B can be difficult and there is a risk of misclassification.

Although this is a single-centre study, data were collected for nearly 4 years in a fairly large study population.

In this study, a lactate cut-off point of 4.0 mmol/L was chosen; however, the optimal cut-off point to define hyperlactatemia is yet to be determined.

Introduction

In clinical practice, plasma lactate levels are usually used as indicators of tissue hypoxia. In critically ill patients, lactate levels ≥4.0 mmol/L are associated with an ∼30% 28-day mortality and therefore serve as good baseline predictors of mortality risk.1 2

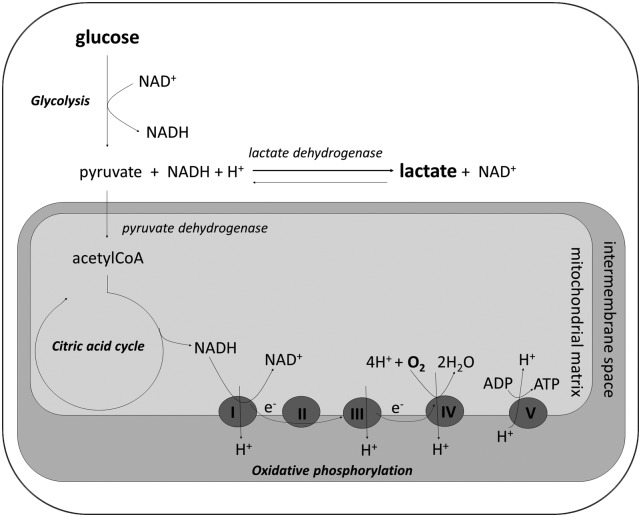

The formation of lactate from pyruvate largely depends on the cytosolic redox state (figure 1). Lactate formation under hypoxic conditions has been designated as type A hyperlactatemia, which is caused by, among others, shock, bowel ischaemia and epileptic insults. In contrast, in type B hyperlactatemia, there is no evidence of a hypoxic condition. This type of hyperlactatemia can result from increased production as well as decreased lactate usage and is the consequence of, among others, use of metformin (haematological) malignancies, liver disease and alcohol abuse.3

Figure 1.

Biochemical pathways that result in lactate formation. Under aerobic conditions, glucose is converted in a stepwise fashion to pyruvate (glycolysis), which subsequently enters the mitochondrion where it is converted to acetylCoA. AcetylCoA is degraded in the citric acid cycle yielding NADH, which serves as an electron (e−) donor. These electrons pass through respiratory complexes I, III and IV, present at the inner mitochondrial membrane, allowing protons (H+) to move to the intermembrane space. Finally, oxygen serves as an electron acceptor (in complex IV) and ATP is generated in complex V when protons move back to the mitochondrial matrix. In type A lactic acidosis, the primary defect is a lack of oxygen causing a halt to oxidative phosphorylation and thus accumulation of NADH. High cytosolic NADH concentrations shift the equilibrium from pyruvate to lactate. The advantage of this process is that it yields two ATP molecules and regenerates NAD+. The latter is of particular importance, since NAD+ is required for glycolysis. In type B lactic acidosis, there is a (non-hypoxic) accumulation of either pyruvate or NADH, which again shifts the equilibrium towards the formation of lactate.

The prevalence, causes and outcomes of hyperlactatemia have been studied extensively for patients at the intensive care unit (ICU),4 5 but data on patients in the emergency department (ED) are scarce. Until now, only a few studies assessed mortality in relatively unselected patients with hyperlactatemia at the ED. These studies reported higher mortality in those with increased lactate levels than in with those with lower values.6–10 Besides these studies, only patients with a specific diagnosis (eg, trauma, pulmonary embolism or sepsis) have been studied in an ED setting.11–15 Of note, all but one9 of these studies were conducted retrospectively and in none, lactate levels were determined on a routine base in all patients. For this reason, we can assume that the studied populations were selected. It is, however, not known to what extent this selection has affected the outcomes. Moreover, none of these studies have made a distinction between type A and B hyperlactatemia when studying the effects on mortality.

The aim of the current study was therefore to assess the outcomes (ICU/medium care unit (MCU) admission, 28-day mortality and readmission within 28 days) in patients with an internal disease presenting to the ED in whom lactate levels were either elevated (≥4.0 mmol/L), <4.0 mmol/L or not determined. Furthermore, we aimed to retrieve how often hyperlactatemia could be classified as type A and B hyperlactatemia and to compare the outcome between these two types.

Materials and methods

Study design

This retrospective study was conducted at the ED of the Maastricht University Medical Centre (MUMC+), which is a secondary and tertiary referral centre in the Netherlands. Patients can present to the ED in one of the following ways: (1) (most commonly) patients can be referred by a general practitioner (whose service is available 24/7) or specialist, (2) in case of a high level of urgency, patients are brought in by ambulance, or (3) (sometimes) patients can present themselves on their own initiative (for more details on the organisation of acute care in the Netherlands, see ref. 16). The department of internal medicine has about 5500 ED visits each year.

Inclusion criteria

Data were collected over a period of almost 4 years (from January 2011 to October 2014). We retrieved all samples of adult patients who were admitted to the hospital by internists at the ED with an elevated arterial lactate (≥4.0, normal value ≤2.2 mmol/L; high lactate group, n=197). This cut-off point for hyperlactatemia was used since a value of ≥4.0 mmol/L is a good predictor of mortality.9 11 Subsequently, two reference groups were constructed: (1) a random sample of patients in whom the lactate was <4.0 mmol/L (lactate <4.0 group, n=200), and (2) a random sample of patients in whom the lactate was not determined because of clinical reasons, that is, the attending physician did not have a clinical indication to measure lactate (no lactate group, n=200). Both control groups were chosen randomly out of those who were admitted to the hospital, and this choice was corrected for date of presentation only, in order to create a sample that was not biased by seasonal influences. All patients had to be 18 years or older and were included only once; repeat visits were excluded.

Data collection

Electronic patient records, consisting of ED admission charts, electronic hospital records and/or discharge letters, were collected. In this extensive electronic patient record, all relevant medical data (including notes from nurses and doctors, and laboratory and radiology results) can be found. To collect all data, a standardised extraction form was used. Collected information included demography (age and gender), vital parameters (systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, temperature, oxygen saturation, respiratory rate), laboratory values (haemoglobin, leucocytes, glucose, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), creatinine and blood gas values including pH, partial pressure of oxygen, partial pressure of carbon dioxide and base excess), medication, medical history, final diagnosis before discharge and date of death. To assess the degree of comorbidity, we used the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), which predicts 10-year mortality and includes several comorbid conditions, such as heart disease and cancer.17

We only used the first lactate sample at the ED. To determine the cause of hyperlactatemia, we first divided the causes into two groups: type A (abnormal tissue oxygenation) and type B (no clinical signs of abnormal tissue oxygenation). We considered the following causes to be type A hyperlactatemia: shock, sepsis, bowel ischaemia, seizures, severe hypoxaemia (arterial oxygen tension <30 mm Hg) or cyanosis, severe hypothermia and severe anaemia (haemoglobin level <5 g/dL).3 We defined shock as SBP below 90 mm Hg or mean arterial pressure (MAP) below 65 mm Hg. Sepsis was defined as the main cause in case two or more systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria ((1) temperature >38.0°C or <36.0°C, (2) heart rate >90 per minute, (3) respiratory rate >20 per minute or arterial carbon dioxide tension <4.3 kPa, (4) leucocytes <4×109 or >12×109 or >10% bands) were present in combination with suspected or proven infection.18 Type B hyperlactatemia was automatically classified when there were no signs of hypoxia and, when the main cause was not clear, cases were classified as type B, ‘unknown’. The cause of the hyperlactatemia was determined by a researcher and two internists, one specialised in acute internal/emergency medicine and one in metabolic diseases, all blinded for the outcome. In case of uncertainty about the principal cause of the hyperlactatemia, consensus was reached for all patients through a panel discussion.

In addition, we assessed the main diagnosis in the lactate <4.0 group and the no lactate group and categorised these as: shock/haemodynamically unstable, sepsis, infection (without sepsis), gastrointestinal diseases, respiratory insufficiency, renal impairment, cancer/side effect of chemotherapy, intoxication (alcohol or drugs abuse), related to diabetes mellitus, hepatic disease and other. Gastrointestinal diseases included bowel ischaemia, Crohn's disease and obstipation. The category ‘related to diabetes mellitus’ included dysregulated diabetes mellitus, use of metformin and ketoacidosis. The category ‘other’ included allergic reactions, delirium and dehydration.

Outcome

The outcome measures we assessed were: length of stay in the hospital, ICU/MCU admissions, readmission within 28 days, and 28-day all-cause mortality (primary end point). The lengths of stay in the hospital and in the ICU/MCU were calculated for those who survived the admission only. Likewise, for calculation of the readmission rate within 28 days, the patients who died within that period were excluded. We compared the outcome measures between the three groups of patients and for type A and B hyperlactatemia.

Statistics

SPSS Statistics V.22 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for the statistical analyses. For categorical data, the χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test were used to test for differences. Continuous data that were distributed normally were analysed with an independent t-test. For continuous data that were not normally distributed after transformation, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. All analyses were corrected for multiple testing using the Hochberg procedure. The 28-day survival curves were obtained using Kaplan-Meier curves and differences were tested using the log-rank test. p Values were considered statistically significant if <0.05.

Results

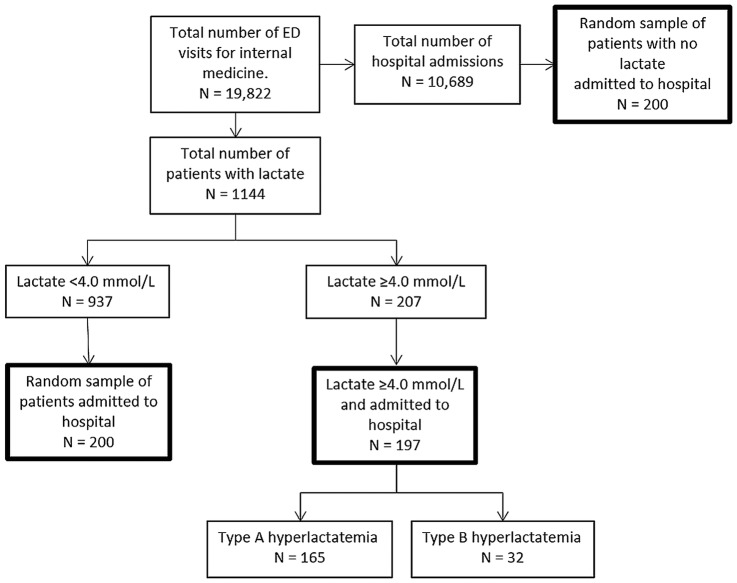

In the nearly 4-year study period, 19 822 patients were assessed by the internist at the ED (figure 2). Lactate levels were determined in 1144 patients (5.8%), which were ≥4.0 mmol/L in 207 patients (18.1%). Of these patients, 197 (95.2%) were admitted. Both reference groups (the lactate <4.0 group and no lactate group) were randomly selected and consisted of 200 patients per group.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of the study population. ED, emergency department.

General characteristics

General characteristics of patients with high lactate, and the two reference groups are presented in table 1. Age and sex distribution was similar in the three groups. The median CCI score in all three groups was 2, but the range was slightly and significantly higher in the high lactate group than in the ‘lactate <4.0 group’. The SBP, MAP and temperature were lower in the high lactate group than in both reference groups. In addition, heart rate, respiratory rate and serum creatinine were higher in the ‘high lactate group’ than in both reference groups. In addition, the same difference was found between the ‘lactate <4.0 group’ and the ‘no lactate group’. The three parameters were higher for the ‘lactate <4.0 group’. Furthermore, oxygen saturation was lower in the ‘lactate <4.0 group’.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| No lactate | Lactate <4.0 | High lactate | p Value no vs <4.0 | p Value no vs high | p Value <4.0 vs high | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=200 | N=200 | N=197 | ||||

| Age in years | 64±18 | 67±16 | 66±16 | 0.123 | 0.653 | 0.696 |

| Sex, female | 100 (50.0) | 94 (47.0) | 86 (43.7) | 0.617 | 0.228 | 0.546 |

| CCI score | 2.0 (0–3) | 2.0 (0–3) | 2.0 (1–4) | 0.700 | 0.036 | 0.058 |

| Lactate | – | 1.7 (1.3–2.3) | 6.2 (4.7–9.3) | |||

| Shock* | 8 (4.0) | 32 (16.0) | 58 (29.4) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| SBP | 133±26 | 126±31 | 113±32 | 0.065 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| MAP | 93±16 | 89±21 | 80±32 | 0.089 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Heart rate | 87±23 | 94±23 | 105±26 | 0.010 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Temperature | 36.9 (36.4–37.4) | 37.1 (36.3–38.2) | 36.6 (35.7–37.8) | 0.061 | 0.102 | 0.003 |

| Oxygen saturation | 98 (96–100) | 97 (93–99) | 97 (93–100) | <0.001 | 0.040 | 0.088 |

| Respiratory rate | 14 (14–20) | 20 (14–25) | 24 (20–30) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Serum creatinine | 117±99 | 186±240 | 205±158 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| Main diagnosis | ||||||

| Shock/haemodynamically unstable | 7 (3.5) | 34 (17.0) | 102 (51.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 7 (3.5) | 23 (11.5) | 32 (16.2) | 0.008 | <0.001 | 0.192 |

| Infection | 55 (27.5) | 45 (22.5) | 0 | 0.299 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal | 31 (15.5) | 17 (8.5) | 11 (5.6) | 0.090 | 0.006 | 0.328 |

| Respiratory insufficiency | 2 (1.0) | 9 (5.5) | 4 (2.0) | 0.186 | 0.400 | 0.518 |

| Renal impairment | 5 (2.5) | 9 (4.5) | 0 | 0.416 | 0.052 | 0.009 |

| Cancer/side effect chemotherapy | 23 (11.5) | 7 (3.5) | 0 | 0.008 | <0.001 | 0.008 |

| Intoxication | 14 (7.0) | 7 (3.5) | 4 (2.0) | 0.354 | 0.081 | 0.543 |

| Diabetes mellitus related | 3 (1.5) | 12 (6.0) | 9 (4.6) | 0.096 | 0.170 | 0.655 |

| Liver disease | 5 (2.5) | 3 (1.5) | 6 (3.0) | 0.950 | 0.770 | 0.903 |

| Other | 36 (18) | 31 (15.5) | 22 (11.2) | 0.592 | 0.195 | 0.476 |

| Unknown | 12 (6.0) | 3 (1.5) | 7 (3.6) | 0.096 | 0.348 | 0.384 |

Data are presented as n (%), mean±SD or as median (IQR).

*Shock was defined as SBP<90 or MAP<65.

Lactate level was given in mmol/L.

Temperature was given in °C.

CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; MAP, mean arterial pressure; SBD, systolic blood pressure.

The ‘high lactate group’ was most often admitted to the hospital with shock (51.8%) and sepsis (16.2%), the ‘lactate <4.0 group’ with infection (22.5%) and shock (17.0%), and the ‘no lactate group’ with infection (27.5%) and gastrointestinal problems (15.5%).

Outcomes

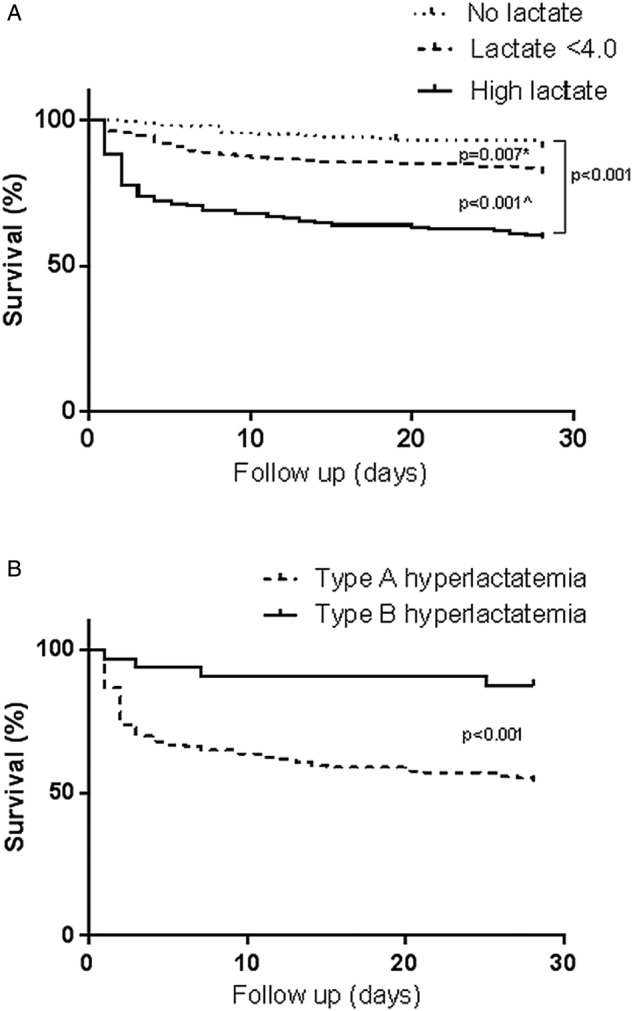

Patients with hyperlactatemia stayed significantly longer in hospital than patients without lactate measurements (median 15 vs 8 days, p<0.001), but not longer than in the ‘lactate <4.0 group’ (13 days, p=0.68; table 2). In addition, the ‘high lactate group’ was more frequently admitted to the ICU/MCU (40.1%) than both the ‘lactate <4.0 group’ (15.0%, p<0.001) and the ‘no lactate group’ (4.5%, p<0.001). The length of stay in the ICU/MCU was not different among the three groups, and neither was the readmission rate within 28 days. However, 28-day mortality in the ‘high lactate group’ (40.6%) was significantly higher than in the ‘lactate <4.0 group’ (18.5%, p<0.001) and the ‘no lactate group’ (9.5%, p<0.001, figure 3A). In addition, mortality was significantly higher in the normal lactate group than in the no lactate group (p=0.007).

Table 2.

Outcomes

| No lactate | Lactate <4.0 | High lactate | p Value no vs <4.0 | p Value no vs high | p Value <4.0 vs high | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=200 | N=200 | N=197 | ||||

| Length of stay | 8 (11) | 13 (14) | 15 (±17) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.683 |

| ICU/MCU admission | 9 (4.5) | 30 (15.0 | 79 (40.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| ICU restrictions | 36 (18.0) | 71 (35.5) | 53 (26.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Length of stay in the ICU/MCU | 3 (2–5) | 6 (3–10) | 3.5 (2–7.5) | 0.114 | 0.349 | 0.220 |

| Readmission <28 days | 29 (15.7) | 20 (12.3) | 18 (16.2) | 0.440 | 1.000 | 0.377 |

| 28-day mortality | 19 (9.5) | 37 (18.5) | 80 (40.6) | 0.007 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 1-year mortality | 47 (23.5) | 62 (31.0) | 109 (55.3) | 0.061 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Data are presented as mean±SD, n (%) or as median (IQR).

The length of stay was given in days.

ICU, intensive care unit; MCU, medium care unit.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves for 28-day survival. (A) High lactate group compared with the lactate <4.0 group and the no lactate group. *p Value=0.007 for the no lactate group in comparison with the lactate <4.0 group. ^p Value <0.001 for the lactate <4.0 group in comparison with the high lactate group. (B) Type A compared with type B hyperlactatemia.

Type A and B hyperlactatemia

To gain more insight into the prognostic value of the underlying cause of hyperlactatemia, two groups were defined based on the absence or presence of tissue hypoxia (type A and B hyperlactatemia, respectively). The majority of the patients with hyperlactatemia (n=197) were classified as type A hyperlactatemia (n=165, 83.8%; table 3). These patients were older (67 vs 57 years, p=0.001) and had higher lactate levels than type B patients (7.5 vs 6.2 mmol/L, respectively, p=0.03). Furthermore, SBP and MAP were lower and serum creatinine was higher in type A than in type B patients. The most common causes of type A hyperlactatemia were shock/haemodynamical instability (61.4%) and sepsis (19.3%), whereas the most common causes of type B hyperlactatemia were related to diabetes mellitus (43.8%) and liver disease (18.8%). Of the 14 patients with hyperlactatemia related to diabetes mellitus, metformin use was identified five times as the main cause.

Table 3.

Patient characteristics with type A and B hyperlactatemia

| Type A | Type B | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N=165 (83.8) | N=32 (16.2) | p Value | |

| Age in years | 67±15 | 57±18 | 0.001 |

| Sex, female (n) | 74 (45.0) | 12 (35.0) | 0.45 |

| CCI score | 2 (1–4) | 2.5 (1–5.0) | 0.34 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 7.8±4.0 | 6.3±2.7 | 0.06 |

| SBP | 108±32 | 135±22 | <0.001 |

| MAP | 77±23 | 97±14 | <0.001 |

| Heart rate | 106±27 | 98±21 | 0.14 |

| Temperature | 36.7 (35.5–38.2) | 36.6 (36.2–37.4) | 0.68 |

| Oxygen saturation | 97 (92–100) | 98 (97–100) | 0.09 |

| Respiratory rate | 24 (20–30) | 24 (15–24) | 0.003 |

| Serum creatinine | 213±162 | 160±125 | 0.09 |

| Main diagnosis (%) | |||

| Shock/haemodynamic ally unstable | 102 (61.4) | 0 | |

| Sepsis | 32 (19.3) | 0 | |

| Gastrointestinal | 11 (6.6) | 0 | |

| Respiratory insufficiency | 6 (3.6) | 0 | |

| Intoxication | 0 | 3 (9.4) | |

| Diabetes mellitus related | 0 | 14 (43.8) | |

| Liver disease | 0 | 6 (18.8) | |

| Other | 15 (9.0) | 3 (9.4) | |

| Unknown | 0 | 6 (18.8) | |

| Outcomes | |||

| Length of stay (days) | 17 (±19) | 8 (±7) | |

| ICU/MCU admission | 74 (63.2) | 5 (19.2) | |

| ICU restrictions | 47 (28.7) | 6 (18.8) | |

| Length of stay in the ICU/MCU (days) | 4 (2–9) | 2 (1.5–4.5) | |

| Readmission <28 days | 15 (17.9) | 3 (11.1) | |

| 28-day mortality | 76 (45.8) | 4 (12.5) | |

| 1-year mortality | 101 (60.8) | 8 (25.0) | |

Data are presented as mean±SD, n (%) or as median (IQR).

CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; ICU, intensive care unit; MAP, mean arterial pressure; MCU, medium care unit; SBD, systolic blood pressure.

Hospital admission was longer for type A patients than for patients with type B hyperlactatemia (17 vs 8 days, p=0.01, table 2). In addition, type A patients were more frequently admitted to the ICU/MCU than type B patients (63.2% vs 19.2%, respectively, p=0.003). All-cause 28-day mortality was significantly higher in type A patients (45.8%) than in type B patients (12.5%, p<0.001, figure 3B).

Discussion

This study has three remarkable findings that deserve in-depth discussion and will impact future research and clinical practice. First, plasma lactate levels are determined in only a small fraction (5.8%) of patients who are treated, assessed and hospitalised by acute internists at the ED. Second, patients in whom plasma lactate has been determined represent a selection, since their clinical characteristics and outcome differ substantially from those in whom plasma lactate was not measured. Finally, the adverse outcome 28-day mortality in patients with hyperlactatemia is predominantly explained by those who have tissue hypoxia, that is, type A hyperlactatemia.

The observed difference in 28-day mortality between the three groups (no lactate group, lactate <4.0 group and high lactate group) most likely reflects a selection of patients for whom ordering a lactate measurement is considered clinically useful in the ED. This selection is probably based on the presence of abnormal vital parameters and not on age, gender or comorbidity, since we did not observe differences regarding these three variables between the three groups, whereas vital parameters such as SBP, heart rate and respiratory rate were more often abnormal in those in whom a lactate level was ordered. It is hypothesised that doctors measure lactate levels when they judge the patient to be seriously ill. Apparently, this clinical assessment is of value, since 28-day mortality rates were higher in the small fraction of patients (5.8%) in whom lactate was ordered. It is anticipated that this selection was also present in previous retrospective studies, which must have influenced their outcomes as well.6–8 10 These studies compared patients with different levels of lactate and found higher mortality in patients with higher lactate levels. This aforementioned selection probably has consequences for the prognostic value of lactate levels. Of note, it is possible that these measured values influence decisions taken at the ED, including the decision whether or not to admit the patient. Therefore, before lactate levels can be used to identify patients at risk for a bad (or good) outcome, prospective studies must be performed in which no selection (based on clinical assessment of severity of disease) is made, but in which a lactate level is determined in each (hospitalised) patient. Before such a study is performed, lactate levels cannot be used for risk stratification at the ED.

In this study, the most common causes of hyperlactatemia were shock (51.8%) and sepsis (16.2%), whereas a study from the UK showed that 25.6% had an infection and 25.4% a non-infectious respiratory cause for hyperlactatemia.7 In our study, the number of patients with a respiratory cause was considerably lower. This might be explained by the fact that we included internal medicine patients only.

Furthermore, our study demonstrates that the distinction between type A and B hyperlactatemia is clinically relevant because the prognosis differs significantly. Patients with type A hyperlactatemia had a significantly higher 28-day mortality than those with type B hyperlactatemia (45.8% vs 12.5%, respectively, p<0.001). The distinction between type A and B hyperlactatemia is, however, sometimes not so easy to make from a clinical and pathophysiological perspective. We tried to reduce misclassification by reviewing the charts by three independent investigators and, if necessary, by discussing the case. Our effort does, however, not resolve all difficulties regarding classifying hyperlactatemia. For example, sepsis is usually assigned to type A hyperlactatemia since hypoxia, caused by dysfunction of the microcirculation, is present.3 However, a concomitant increase in β-adrenergic activity also drives glycolysis and thereby the production of ‘non-hypoxic’ (type B) lactate.19 For this reason and the high mortality of type A hyperlactatemia, it is probably safer to treat all patients with hyperlactatemia in the acute setting at the ED as having type A hyperlactatemia by optimising tissue oxygen delivery. However, once it is clear that tissue hypoxia is not present (anymore), non-hypoxic causes—which generally require different management—need to be considered. This study clearly shows that type B hyperlactatemia is not a rare phenomenon (16.2%).

The observed association between type B hyperlactatemia and diabetes mellitus is accounted for by a diversity of factors. First, metformin, which acts on a mitochondrial redox shuttle,20 predisposes to lactic acidosis in particular when renal function is impaired.21 Second, it has been suggested that diabetic ketoacidosis is accompanied by hyperlactatemia, independent of blood pressure.22 Finally, we recently presented a series of remarkably similar cases of young patients with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes who presented with hepatomegaly (resulting from glycogen accumulation) and hyperlactatemia, all of which resolved on improvement of glucose control.23

This study has some limitations. Although this is a single-centre study, data were collected for nearly 4 years in a fairly large study population. Furthermore, only the first known lactate was investigated in this study; further fluctuations or clearance of lactate was taken into account. The clearance of lactate may be of more prognostic value than one single measurement.24 However, we aimed to study the prognostic value of lactate in the setting of an ED, where, in most cases, only a first lactate is available. In this study, analogous to other ED studies, a lactate cut-off point of 4.0 mmol/L was chosen.7 9 10 However, the optimal cut-off point to define hyperlactatemia is yet to be determined. As aforementioned, there is a risk of misclassification between types of hyperlactatemia. We tried to reduce this by reviewing the charts by three independent investigators and, if necessary, by discussing the case. Last, the choice whether or not to admit a patient to the ICU/MCU will be influenced by the availability of beds and choices of patients and family. Therefore, mortality, and not ICU admission, was considered to be the primary end point.

The major advantage of this study is that it has included a real-life cohort, also consisting of a selection of patients in whom no lactate was measured. Owing to this selection, we believe that valuable lessons can be learnt. This selection may be influenced by local work-up protocols. Therefore, our results should be validated in a multicentre population.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the prognostic value of lactate depends largely on the underlying cause and the population in which lactate has been measured. Patients in the ED with hyperlactatemia who are hospitalised have an extremely poor prognosis (28-day mortality 40.6%), especially when type A hyperlactatemia is present (28-day mortality 45.8%). It is recommended that all patients with high lactate in the ED be initially treated as a type A hyperlactatemia, given the poor prognosis. Since in daily practice plasma lactate measurements at the ED are confined to a selected group with a worse prognosis than the group with no lactate measurement, prospective studies evaluating the use of lactate for risk stratification at the ED are eagerly awaited.

Footnotes

Contributors: DPAvdN acquired and analysed the data and drafted the article. MCGJB contributed to the design of the research, the interpretation of data for the work, helped with the statistical analysis and revised the article. PMS designed the research, interpreted the data and revised the article. All authors have provided final approval of the version published and are in agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the MUMC+.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Mikkelsen ME, Miltiades AN, Gaieski DF et al. Serum lactate is associated with mortality in severe sepsis independent of organ failure and shock. Crit Care Med 2009;37:1670–7. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819fcf68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee YR, Powell N, Bonatti H et al. Early development of lactic acidosis with short term linezolid treatment in a renal recipient. J Chemother 2008;20:766–7. 10.1179/joc.2008.20.6.766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kraut JA, Madias NE. Lactic acidosis. N Engl J Med 2014;371:2309–19. 10.1056/NEJMra1309483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juneja D, Singh O, Dang R. Admission hyperlactatemia: causes, incidence, and impact on outcome of patients admitted in a general medical intensive care unit. J Crit Care 2011;26:316–20. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kruse O, Grunnet N, Barfod C. Blood lactate as a predictor for in-hospital mortality in patients admitted acutely to hospital: a systematic review. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2011;19:74 10.1186/1757-7241-19-74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haidl F, Brabrand M, Henriksen DP et al. Lactate is associated with increased 10-day mortality in acute medical patients: a hospital-based cohort study. Eur J Emerg Med 2015;22:282–4. 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Datta D, Walker C, Gray AJ et al. Arterial lactate levels in an emergency department are associated with mortality: a prospective observational cohort study. Emerg Med J 2015;32:673–7. 10.1136/emermed-2013-203541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manzon C, Barrot L, Besch G et al. Capillary lactate as a tool for the triage nurse among patients with SIRS at emergency department presentation: a preliminary report. Ann Intensive Care 2015;5:7 10.1186/s13613-015-0047-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barfod C, Lundstrøm LH, Lauritzen MM et al. Peripheral venous lactate at admission is associated with in-hospital mortality, a prospective cohort study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2015;59:514–23. 10.1111/aas.12503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedersen M, Brandt VS, Holler JG et al. Lactate level, aetiology and mortality of adult patients in an emergency department: a cohort study. Emerg Med J 2015;32:678–84. 10.1136/emermed-2014-204305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shapiro NI, Howell MD, Talmor D et al. Serum lactate as a predictor of mortality in emergency department patients with infection. Ann Emerg Med 2005;45:524–8. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanni S, Jiménez D, Nazerian P et al. Short-term clinical outcome of normotensive patients with acute PE and high plasma lactate. Thorax 2015;70:333–8. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang Y, Choi J, Kim D et al. Clinical predictors of adverse outcome in severe sepsis patients with lactate 2-4 mM admitted to the hospital. QJM 2015;108:279–87. 10.1093/qjmed/hcu186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Musikatavorn K, Thepnimitra S, Komindr A et al. Venous lactate in predicting the need for intensive care unit and mortality among nonelderly sepsis patients with stable hemodynamic. Am J Emerg Med 2015;33:925–30. 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lokhandwala S, Moskowitz A, Lawniczak R et al. Disease heterogeneity and risk stratification in sepsis-related occult hypoperfusion: a retrospective cohort study. J Crit Care 2015;30:531–6. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thijssen WA, Giesen PH, Wensing M. Emergency departments in the Netherlands. Emerg Med J 2012;29:6–9. 10.1136/emermed-2011-200090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramiarina RA, Ramiarina BL, Almeida RM et al. Comorbidity adjustment index for the international classification of diseases, 10th revision. Rev Saude Publica 2008;42:590–7. 10.1590/S0034-89102008000400003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med 2008;36:296–327. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000298158.12101.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levy B, Desebbe O, Montemont C et al. Increased aerobic glycolysis through beta2 stimulation is a common mechanism involved in lactate formation during shock states. Shock 2008;30:417–21. 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318167378f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madiraju AK, Erion DM, Rahimi Y et al. Metformin suppresses gluconeogenesis by inhibiting mitochondrial glycerophosphate dehydrogenase. Nature 2014;510:542–6. 10.1038/nature13270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eppenga WL, Lalmohamed A, Geerts AF et al. Risk of lactic acidosis or elevated lactate concentrations in metformin users with renal impairment: a population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care 2014;37:2218–24. 10.2337/dc13-3023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox K, Cocchi MN, Salciccioli JD et al. Prevalence and significance of lactic acidosis in diabetic ketoacidosis. J Crit Care 2012;27:132–7. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.07.071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brouwers MC, Ham JC, Wisse E et al. Elevated lactate levels in patients with poorly regulated type 1 diabetes and glycogenic hepatopathy: a new feature of Mauriac syndrome. Diabetes care 2015;38:e11–12. 10.2337/dc14-2205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Z, Xu X. Lactate clearance is a useful biomarker for the prediction of all-cause mortality in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis*. Crit Care Med 2014;42:2118–25. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]