Abstract

Background

Communication and teamwork failures have frequently been identified as the root cause of adverse events and complications in surgery. Few studies have examined contextual factors that influence teams’ non-technical skills (NTS) in surgery. The purpose of this prospective study was to identify and describe correlates of NTS.

Methods

We assessed NTS of teams and professional role at 2 hospitals using the revised 23-item Non-TECHnical Skills (NOTECHS) and its subscales (communication, situational awareness, team skills, leadership and decision-making). Over 6 months, 2 trained observers evaluated teams’ NTS using a structured form. Interobserver agreement across hospitals ranged from 86% to 95%. Multiple regression models were developed to describe associations between operative time, team membership, miscommunications, interruptions, and total NOTECHS and subscale scores.

Results

We observed 161 surgical procedures across 8 teams. The total amount of explained variance in NOTECHS and its 5 subscales ranged from 14% (adjusted R2 0.12, p<0.001) to 24% (adjusted R2 0.22, p<0.001). In all models, inverse relationships between the total number of miscommunications and total number of interruptions and teams’ NTS were observed.

Conclusions

Miscommunications and interruptions impact on team NTS performance.

Keywords: miscommunications, interruptions, teamwork, non-technical skills, surgical team, NOTECHS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

While we found relationships between miscommunications, interruptions and surgical teams’ non-technical skills (NTS), the causal sequence between predictors and the outcome cannot be established. However, the design allowed us to describe statistical associations and identification of some potential confounders.

Surgical teams’ NTS were assessed using direct observation and so it is possible for individuals to alter their practices giving rise to the potential for the Hawthorne effect. Nevertheless, contemporaneous observation is preferable to self-report which gives rise to an unintentional reporting bias.

Measures on which observations were based may be considered somewhat subjective as they relied on observers’ ability to interpret events. However, observers were experienced in observational research and trained in observational research and human factors.

There is potential for selection bias as surgical teams were purposively selected based on participants’ willingness to be observed. Despite this, there was variability in NTS scores.

Introduction

Compared with other hospital settings, medical errors in the operating room (OR) can have catastrophic consequences for patients. Adverse events and malpractice claims have been linked to teamwork failures in surgery.1–5 Deficits in teamwork behaviours were identified as a root cause in 63% of all the sentinel events reviewed by the Joint Commission between 2004 and 2013.6 While human error is inevitable and cannot be completely eliminated, the importance of linking the safety of surgery to team culture is increasingly recognised.7–9 Fostering a climate of teamwork and collaboration, along with safety minded work processes that focus on error prevention, is the ultimate goal of healthcare organisations.

Nevertheless, surgical errors need to be understood in the context of the surgical team. Unique challenges stem from the overlapping but different interprofessional expertise and roles among members, ad hoc team membership, unstructured and variable communications, frequent distractions, technology, procedural complexity and competing priorities.10–15 Several studies have described the sources and frequencies of intraoperative interruptions.14 16 17 The results of these studies identified that equipment problems, telephone calls, conversation and environment problems (eg, noise) were major sources of distractions that influenced team performance. It is therefore hardly surprising that as much as 30% of information gets lost during case-related exchanges.9 18 Recent research suggests that omissions in team communications related to providing members with updates about the progress of an operation comprised up to 36% of all observed communication errors.19 Since surgical teams often work together on an ad hoc basis, a lack of prior working experience has the potential to impact on team dynamics. Team familiarity, defined as a core group of individuals who work together regularly, and who share a similar mental model,20 has been identified as an important element of effective teamwork.14 21 An earlier observational study found that fewer miscommunications occurred in teams with a history of working together.14 Recently, results of an Australian observational study suggested a positive association between team familiarity and instrument nurses’ non-technical skills (NTS) performance across 182 surgical procedures.10 Other studies, using retrospective designs, have found associations between team familiarity and reductions in postoperative morbidity following cardiac and major abdominal surgeries.21 22

As a means to increase surgical safety, researchers have focused on communication, leadership, situational awareness and decision-making, termed collectively as NTS in surgery. NTS are the cognitive (ie, decision-making and situational awareness) and interpersonal skills (ie, communication, teamwork and leadership) that complement the individual's technical knowledge.23 Previous research indicates that communication is key to the performance of successful teams. Effective and timely transfer of information enables team processes and states such as coordination, cooperation, conflict resolution and sitational awareness.9 11 24 The development of astute NTS is critical to patient safety, yet surgical teams are challenged by the increasing technical complexity of surgery and high acuity of patients who are older and have multiple comorbidities.8 Moreover, there is a lack of research that examines the impact that environmental factors have on teams’ NTS performance. In this prospective study, we hypothesised that longer surgeries, limited team familiarity, miscommunications and interruptions negatively influenced teams’ use of NTS. A better understanding of the factors that impinge on teamwork behaviours will help us to design strategies to improve NTS performance.

Methods

This was a prospective, observational study of teams’ use of NTS during surgery. Two Australian metropolitan hospitals 70 km from each other, each with a similar case mix, specialising in all surgical specialties, were included to generate results that would be applicable across a variety of procedures. In each hospital, four surgical teams comprising of anaesthetic and surgical consultants, their registrars, and instrument/circulating nurses were observed. Teams and surgical procedures across each hospital were purposively chosen to ensure maximum variation relative to case complexity, particular procedures within specialties, team membership and surgical experience. In hospital A, teams from paediatric, thoracic, orthopaedic and general surgery were observed on a weekly basis across 20–25 surgeries. In hospital B, a similar number of surgeries was observed with cardiac, vascular, upper gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary teams.

Observational data for each hospital were collected during 2015, with an observer located at each hospital. Prior to the observation period, both observers underwent specific training in the use of the observational tool which included the Non-TECHnical Skills (NOTECHS) system. The observers pilot tested the tool and minor changes made to its formatting. During the piloting process, regular meetings were held with the co-researchers to ensure greater clarification of recorded events and refine coding. Both observers were trained in human factors and observational research methods. To ensure methodological consistency, inter-rater checks with 10% of cases at each hospital site were performed during the observation period by the lead author, also trained in human factors. Inter-rater agreement across hospital sites ranged from 86% to 95%. A single observer was present during each procedure and collected data using prespecified checklists and freehand notes. Observations started when the patient entered the OR (prior to anaesthesia) and ended when the patient left the room. During each surgical procedure, observers documented explanatory field notes to supplement the structured observations to better understand contextual factors. Observational data were collected in 2015 over 6 months.

Institutional ethics approvals were given by the participating hospitals and the university. Participants signed a consent form and were advised of their right to confidentiality and anonymity, and to withdraw at any time during data collection. Patients whose operations were observed were informed of the likelihood of observations taking place and given the chance to opt out.

Observational measures

We used the revised NOTECHS scale,25 which was originally developed in the aviation industry for crew resource management. The NOTECHS provides comprehensive behavioural descriptors for each of its subscales and so requires less training prior to use. In surgery, it has been shown to differentiate between good and poor behaviours, and thus has demonstrated good construct validity.25 In the revised NOTECHS, five subscales of NTS are assessed: (A) communication and interaction; (B) situational awareness and vigilance; (C) team skills; (D) leadership and managerial skills; and (E) decision-making in a surgical crisis. Each domain is measured on a seven-point scale to rate each item, with 1=not done through to 6=done very well, and 0=not applicable.25 Total NOTECHS scores range from 5 to 23, with higher scores indicative of better overall performance on all five subscales. Scores for individual subscales were as follows: subscales A and B scores ranged from 4 to 24 while subscales C–E scores ranged from 5 to 30. The ‘not applicable’ option meant that a specific item was not relevant or could not be rated on the basis that the behaviour was not observed. However, participant NOTECHS scores were not affected by a reduced score for non-observed behaviours. ‘Not applicable’ scores were replaced by the participant's individual item mean. In this study, since all subscales were considered of equal importance, total NOTECHS scores were calculated by the number of items (ie, 23) as the denominator. Scores for total NOTECHS and its individual subscales were calculated using the mean of all individual team members’ NOTECHS total scores. We also calculated the mean NOTECHS scores based on professional role (ie, surgeon, anaesthetist, nurse).

In this study, we drew on the literature for definitions and measurement of the observational variables relative to team familiarity, miscommunication and interruption events. Team familiarity was defined as a core membership of three members (ie, surgeon, anaesthetist, instrument and/or circulating nurses) who had worked together, weekly or fortnightly, for a minimum of 3 months.26 Prior to initiation of each surgical procedure, the senior nurse in the room was asked by the observer about regularity, stability and the length of time individual team members had worked together. The number of familiar team members for each procedure were tallied and recorded. We used Lingard et al's18 27 taxonomy to classify miscommunications (ie, audience, content, occasion, experience). Interruptions were classified according to Healey et al's16 28 framework (ie, procedural, conversational). For each procedure, we tallied the number of miscommunications and interruptions in each of their respective categories. In some instances, it was possible that a single miscommunication or interruption could be placed into more than one category. As such, the primary prompt of the miscommunication or interruption was deemed to categorise the event. Operative time included the time from patient skin preparation to the application of the final wound dressing.

Analyses

All analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS; V.23, IBM, New York, New York, USA). Data were cleaned and a random sample of 20% was checked for accuracy. Descriptive analysis included absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies to analyse categorical variables (discipline/role, surgical specialty), while means/SDs or medians/IQR were used for continuous data (ie, operative time, number of interruptions, miscommunications, NOTECHS scores). The independent variables, operative time, team familiarity, number of interruptions and miscommunications, were subsequently included as covariates in simultaneous multiple regression models with the dependent variable, NTS (measured by NOTECHS). A p value of <0.05 was considered significant and 95% CIs were used. Cohen's f2 was used to calculate effect size.

Sample size calculation

Our a priori sample size estimate was based on the 20:1 rule which states that the ratio of the sample size to the number of parameters in a regression model should be at least 20 cases for each predictor variable in the regression model.29 30 Since four predictor variables were proposed in this study, a sample size of 100 was considered sufficient in a parsimonious regression model.

Results

Across both hospital sites, a total of 161 operations were observed (hospital A n=80; hospital B n=81). The number of surgeries observed for each team ranged from 20 to 25 with the exception of the thoracic team. Owing to the retirement of the consultant surgeon in the thoracic team, only six surgical procedures were observed in this specialty. In total, 481 individual participants’ observational data were collected (hospital A n=243; hospital B n=238). The mean length of surgery across both sites was 116.3 min (±96.5; site A=78.5 min, ±71.2; site B, 153.7 min, ±103.8). Across the 160 procedures we observed, consistency in team membership ranged from 3 to 8 team members. On average, there were seven team members present across all procedures including two surgeons, two anaesthetists and three nurses. Table 1 shows case characteristics for each surgical specialty relative to number of procedures in each specialty, operative time, team membership and NOTECHS scores (by subscales A–E and mean total). Subscale E, decision-making during a surgical crisis was observed in only 40–50% of cases as these situations were often not observed during field work. Of the eight teams observed, the hepatobiliary team had the highest NOTECHS mean scores (20.7±2.3) while the cardiac team had the lowest (19.1±3.5). Table 2 displays the descriptive results for NTS performance based on professional role. Observed NTS performance among surgeons and anaesthetists was comparable; however, nurses’ scores were somewhat lower.

Table 1.

Case characteristics (n=161 surgical procedures)

| Surgical specialty | Number of procedures observed in each specialty (n/total %) | Operative time (min) Mean (SD) |

Team membership Median (IQR) |

Total NOTECHS scores Mean (SD)* |

Subscale A communication and interaction Mean (SD)† |

Subscale B vigilance/situation awareness Mean (SD)† |

Subscale C team skills Mean (SD)† |

Subscale D leadership and management skills Mean (SD)† |

Subscale E decision-making in a crisis Mean (SD)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | 25 (15.5) | 119.5 (85.7) | 4 (1) | 18.7 (3.1) | 19.8 (3.5) | 20.0 (3.6) | 23.9 (4.5) | 23.8 (4.7) | 24.3 (4.7) |

| Orthopaedic | 25 (15.5) | 82.3 (66.6) | 4 (2) | 20.3 (2.4) | 21.0 (3.1) | 21.8 (2.6) | 25.9 (3.1) | 26.7 (3.5) | 26.3 (4.0) |

| Paediatric | 25 (15.5) | 35.0 (26.1) | 3 (2) | 20.5 (2.7) | 21.5 (2.8) | 21.9 (3.0) | 26.1 (4.5) | 26.5 (4.1) | 27.1 (3.5) |

| Thoracic | 6 (3.7) | 74.1 (55.8) | 4 (3) | 19.6 (2.3) | 21.6 (3.0) | 20.8 (3.0) | 25.2 (3.1) | 24.6 (3.7) | 25.1 (2.4) |

| Cardiac | 20 (12.4) | 234.4 (97.5) | 8 (3) | 18.4 (2.6) | 19.1 (3.5) | 20.7 (2.7) | 22.8 (4.3) | 22.5 (4.4) | 24.8 (4.2) |

| Hepatobiliary | 20 (12.4) | 165.3 (122.2) | 5 (1) | 20.7 (2.3) | 22.1 (2.4) | 22.1 (2.5) | 26.7 (3.3) | 25.7 (3.8) | 27.1 (4.0) |

| Upper GI | 20 (12.4) | 109.8 (78.6) | 4 (2) | 20.5 (2.6) | 22.1 (2.9) | 22.1 (2.5) | 26.2 (3.7) | 25.1 (4.1) | 27.0 (4.7) |

| Vascular | 20 (12.4) | 105.4 (51.7) | 6 (2) | 20.1 (2.4) | 22.1 (2.5) | 21.9 (2.3) | 25.3 (4.3) | 23.9 (4.6) | 26.6 (4.1) |

*Total NOTECHS scores range 1–23.

†Subscales A and B scores in domain range 4–24, subscales C–E scores in domain range 5–30.

GI, gastrointestinal; NOTECHS, Non-TECHnical Skills.

Table 2.

Descriptives of NOTECHS performance based on professional role (n=481)

| Surgeon consultant/registrar | Anaesthetic consultant/registrar | Scrub/scout nurse | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total NOTECS* | |||

| n | 161 | 158 | 160 |

| Mean | 20.5 | 20.6 | 18.9 |

| SD | 2.1 | 2.4 | 3.2 |

| 95% CI | 20.1 to 20.8 | 19.8 to 20.6 | 18.4 to 19.4 |

| Range | 14.5–23.0 | 11.64–23.0 | 10.04–23.00 |

| Subscale A, communication and interaction† | |||

| n | 161 | 158 | 160 |

| Mean | 21.4 | 21.5 | 20.4 |

| SD | 2.8 | 2.87 | 3.7 |

| 95% CI | 20.9 to 21.8 | 21.0 to 22.0 | 19.81 to 20.96 |

| Range | 10.0–24.0 | 10.0–24.0 | 10.00–24.00 |

| Subscale B, vigilance/situational awareness† | |||

| n | 161 | 158 | 160 |

| Mean | 22.2 | 21.3 | 20.8 |

| SD | 2.2 | 2.6 | 3.6 |

| 95% CI | 21.8 to 22.5 | 20.9 to 21.7 | 20.3 to 21.4 |

| Range | 16.0–24.0 | 11.0–24.0 | 8.0–24.0 |

| Subscale C, team skills | |||

| n | 161 | 158 | 160 |

| Mean | 25.9 | 25.9 | 24.1 |

| SD | 3.5 | 4.0 | 4.6 |

| 95% CI | 25.3 to 26.4 | 25.2 to 26.5 | 23.3 to 24.8 |

| Range | 15.0–30.0 | 11.00–30.0 | 10.0–30.0 |

| Subscale D, leadership and management skills | |||

| n | 161 | 158 | 160 |

| Mean | 25.5 | 25.5 | 23.8 |

| SD | 4.1 | 3.9 | 4.8 |

| 95% CI | 24.9 to 26.2 | 24.9 to 26.1 | 23.0 to 24.6 |

| Range | 14.0–30.0 | 12.5–30.0 | 10.0–30.0 |

| Subscale E, decision-making in a crisis | |||

| n | 161 | 158 | 160 |

| Mean | 27.5 | 27.0 | 23.6 |

| SD | 2.83 | 3.16 | 5.2 |

| 95% CI | 27.1 to 28.0 | 26.6 to 27.6 | 22.8 to 24.4 |

| Range | 18.0–30.0 | 17.0–30.0 | 9.0–30.0 |

*Total NOTECHS scores range 1–23.

†Subscales A and B scores in domain range 4–24, subscales C–E scores in domain range 5–30.

NOTECHS, Non-TECHnical Skills.

During each surgical procedure, the observers recorded field notes to better understand and explain the contextual happenings during assessment of teams’ NTS. The following two field notes are provided as exemplars of team communications from the highest and lowest performing teams on the NOTECHS. Ensuring that both the anaesthetic and surgical teams had a similar mental model in relation to the procedure was important:

Prior to commencing a liver resection procedure, the Consultant and Registrar Surgeons and the Anaesthetic Consultant participated in a detailed prebriefing about the patient's medical history and anticipated difficulties/challenges from their discipline perspectives. These physicians had never worked together before. Prebriefings between the lead surgeon and anaesthetist were commonplace in this room and were observed to occur in 70% of the cases observed. (Hepatobiliary: Hepatectomy, Case #18)

The following fieldnote illustrates an observed miscommunication between the surgeon and perfusionist:

Consultant Surgeon to Perfusionist, “Give pledgia.”

Perfusionist: “Give another one?”

Consultant Surgeon: “‘Have you finished with the previous one?”

Perfusionist: “Yes”. Consultant Surgeon appears to be unaware of pledgia delivery time. There was no further inquiry from the Consultant Surgeon. (Cardiac: CABGS×4, Case #9)

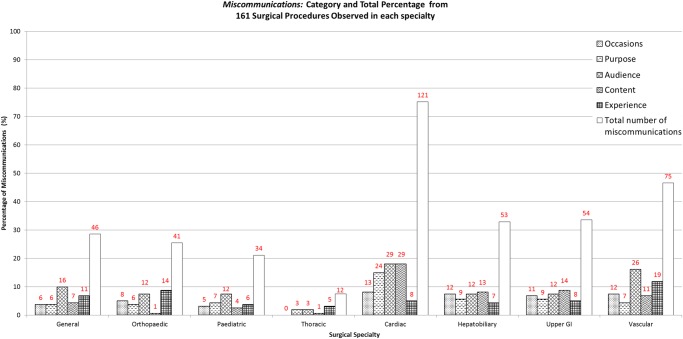

Across the 161 procedures, the number of miscommunications totalled 436 (hospital A n=133; hospital B n=303). The highest number of miscommunications was observed in cardiac surgery (n=121). Throughout the observed procedures, interruptions occurred in 106/161 (65.8%) cases. Of the 106 procedures where interruptions were observed, procedural interruptions occurred at least once in 92 procedures (86.8%; hospital A n=118; hospital B n=76). The number and types of miscommunications and interruptions for each surgical specialty appear in figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Total number of miscommunications across eight specialties. GI, gastrointestinal.

Figure 2.

Total number of interruptions across eight specialties. GI, gastrointestinal.

Multivariate regression analyses

Table 3 shows the six multiple regression models for total NOTECHS scores and its individual subscales (A–E). The total amount of explained variance in NOTECHS and its individual subscales ranged from 14% (adjusted R2 0.12, p<0.001) to 24% (adjusted R2 0.22, p<0.001). In all six regression models, the total number of miscommunications and interruptions were consistently significant predictors of teams’ NTS (table 3). Operative time and team membership were non-significant.

Table 3.

Regression models for predictors of total NOTECHS and each NOTECHS domain (n=161 surgical procedures)

| 95% CI |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Predictor variable | β | SE | β | t | Significance | Lower bound | Upper bound |

| *Team NOTECHS | Constant | 20.70 | 0.38 | – | 55.01 | <0.001 | 19.96 | 21.45 |

| Team familiarity | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.893 | −0.15 | 0.18 | |

| Operative time | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.97 | 0.334 | −0.00 | 0.01 | |

| Miscommunications | −0.27 | 0.06 | −0.41 | −4.82 | <0.001 | −0.38 | −0.16 | |

| Interruptions | −0.29 | 0.12 | −0.19 | −2.44 | 0.016 | −0.52 | −0.05 | |

| †Subscale A, communication and interaction | Constant | 22.17 | 0.44 | – | 50.18 | <0.001 | 21.30 | 23.05 |

| Team familiarity | −0.04 | 0.10 | −0.04 | −0.42 | 0.674 | −0.23 | 0.15 | |

| Operative time | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.07 | −0.66 | 0.512 | 0.00 | 0.01 | |

| Miscommunications | −0.23 | 0.07 | −0.31 | −3.57 | <0.001 | −0.36 | −0.10 | |

| Interruptions | −0.35 | 0.14 | −0.21 | −2.54 | 0.012 | −0.62 | −0.08 | |

| ‡Subscale B, vigilance/situation awareness | Constant | 21.76 | 0.41 | – | 55.62 | <0.001 | 20.96 | 22.56 |

| Team familiarity | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 1.04 | 0.299 | −0.08 | 0.27 | |

| Operative time | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 1.40 | 0.163 | −0.00 | 0.01 | |

| Miscommunications | −0.23 | 0.06 | −0.33 | −3.83 | <0.001 | −0.35 | −0.11 | |

| Interruptions | −0.36 | 0.13 | −0.23 | −2.86 | 0.005 | −0.61 | −0.11 | |

| §Subscale C, team skills | Constant | 26.72 | 0.58 | – | 46.19 | <0.001 | 25.58 | 27.87 |

| Team familiarity | −0.04 | 0.13 | −0.03 | −0.32 | 0.753 | −0.29 | 0.21 | |

| Operative time | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.41 | 0.686 | −0.01 | 0.01 | |

| Miscommunications | −0.38 | 0.09 | −0.38 | −4.49 | <0.001 | −0.55 | −0.21 | |

| Interruptions | −0.30 | 0.18 | −0.13 | −1.65 | 0.101 | −0.66 | 0.06 | |

| ¶Subscale D, leadership and management skills | Constant | 26.67 | 0.56 | – | 47.72 | <0.001 | 25.57 | 27.78 |

| Team familiarity | −0.13 | 0.12 | −0.09 | −1.09 | 0.277 | −0.38 | 0.11 | |

| Previous training | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 1.59 | 0.115 | −0.00 | 0.01 | |

| Miscommunications | −0.57 | 0.08 | −0.51 | −6.26 | <0.001 | −0.68 | −0.35 | |

| Interruptions | −0.21 | 0.18 | −0.09 | −1.23 | 0.222 | −0.56 | 0.13 | |

| **Subscale E, decision-making in a crisis | Constant | 26.65 | 0.56 | – | 47.92 | <0.001 | 25.55 | 27.75 |

| Team familiarity | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 1.31 | 0.192 | −0.08 | 0.40 | |

| Operative time | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.793 | −0.01 | 0.01 | |

| Miscommunications | −0.30 | 0.08 | −0.32 | −3.63 | <0.001 | −0.46 | −0.14 | |

| Interruptions | −0.45 | 0.17 | −0.21 | −2.58 | 0.011 | −0.79 | −0.11 | |

*R=0.43, R² 0.18, R² Adj 0.16, F=8.65 df(4/160), p<0.001, (f2)=0.22.

†R=0.37, R² 0.14, R² Adj 0.12, F=6.22 df(4/160), p<0.001, (f2)=0.16.

‡R=0.37, R² 0.14, R² Adj 0.12, F=6.23 df(4/160), p<0.001, (f2)=0.16.

§R=0.41, R² 0.17, R² Adj 0.15, F=7.82 df(4/160), p<0.001, (f2)=0.20.

¶R=0.49, R² 0.24, R² Adj 0.22, F=12.27 df(4/160), p<0.001, (f2)=0.32.

**R=0.38, R² 0.15, R² Adj 0.12, F=6.56 df(4/160), p<0.001, (f2)=0.18.

Adj, adjusted; NOTECHS, Non-TECHnical Skills.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the correlates of teams’ NTS. This study is also one of the largest single observational studies in this field. Notably, we found inverse associations between the number of miscommunications and interruptions and team NTS across all NOTECHS subscales, suggesting that the fewer miscommunications and interruptions there are, the higher the teams’ NTS performance. These results seem intuitive, but this study is the first to provide evidence generated through structured observations conducted in real time (rather than in simulated environments). In this study, we observed fewer interruptions as compared with miscommunications, with the highest number of interruptions seen in the general surgery team. Many interruptions may be considered acceptable when there are no immediate demands from patient care, but are clearly less appropriate at busy times or when problems occur.31 Some interruptions are essential for information sharing, or to talk to and reassure patients, but managing interruptions and distractions is a crucial skill that requires individuals to refocus on their primary task.14 Interruptions have been identified as a major contributor to loss of vigilance in anaesthetists.31 While teams and individuals scored reasonably highly on the NOTECHS and its subscales, the lowest NTS performance was observed in relation to vigilance/situation awareness across all teams. Clearly, miscommunications and interruptions have the potential to erode individual and distributed situational awareness in surgery.14 31

The hepatobiliary team had the highest NTS performance, as indicated by their NOTECHS scores. The hepatobiliary team also had the lowest number of miscommunications during the fieldwork period. In field notes, the observer described routine preoperative discussions that occurred between physicians prior to case start, the low levels of environmental and conversational noise, and frequent occasions of closed loop communications between members, which heightened levels of distributed situational awareness among team members. Taken together, these features contributed to the smooth coordination of team tasks and patient care processes during these lists.

Conversely, the cardiac team demonstrated the lowest NTS performance, which was unexpected given that this team had clearly defined roles and a small repertoire of procedures that were ‘routine’ and well rehearsed. Remarkably, this team also had the greatest number of observed miscommunications during the field work period. Notably, the degree of difficulty and complexity, technical skills, stress, and patients’ instability and acuity may be the highest in cardiac surgery.13 32 Observer described (in field notes) the considerable environmental, technological and team-related challenges experienced by the cardiac during the surgery, which added to case complexity. For instance, the high noise levels in this room were attributed to team communications and technology, for example, cross-conversations, repeated requests from the surgeon to the perfusionist who was distracted by other team members and/or equipment problems, as well as incessant alarms during the intraoperative period. Additionally, procedural and conversational interruptions as a result of the entry of external team members into the room to ask questions, and the referral of cell phone calls that occasionally required the recipient to leave the room, contributed to lower observed NTS in the cardiac team.

Although we had good sampling across surgical specialties and procedures, it is difficult to speculate about whether the differences in NTS performance can be attributed to hospital sites, specialties, surgical teams or individuals. The two hospital sites chosen were similar in relation to case mix, patient acuity and surgical activity. However, the selection of specialties varied in each hospital, which may, in part, explain the differences in NTS we observed across teams. The observed differences may also be attributed to particular individuals, that is, good leadership of the consultant surgeon has been linked with effective team behaviour and task accomplishment.33 Arguably, surgeons may establish aspects of leadership prior to the start of the procedure to condition intraoperative team performance. For instance, using the surgical safety checklist or having a team briefing can contribute to building the team's shared mental model, and hence increasing distributed situational awareness.34

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths but we also recognise some limitations: First, while we found relationships between miscommunications, interruptions and surgical teams’ NTS, temporal order and causality cannot be established. Thus, there may be some competing explanations for these results. Nevertheless, the design does allow statistical associations and identification of some potential confounders, but not all have necessarily been identified. Second, surgical teams’ NTS were evaluated through direct observation. Although most research in this area has been largely observational and has focused on refining this methodology,9 16 17 26 35 individuals may have altered their practices in response to being observed. Nevertheless, contemporaneous observation is a preferred method to self-report which could be flawed (giving rise to response bias). The observational nature of the NOTECHS allowed us to measure performance as it happened, rather than a retrospective self-report. Third, the measures on which the observations were based may be considered somewhat subjective as they rely on observers’ ability to interpret events. Yet the observers were experienced OR nurses, trained in observational research and in human factors. Inter-rater consistency between observers was acceptable. Additionally, the measures we used have been previously validated in this field.25–27 35 Fourth, surgical teams were purposively selected based on participants’ willingness to be observed. Thus, there is the potential for selection bias. However, there was variability in NOTECHS scores. Finally, in this sample, the amount of explained variance in NTS and its subscales, while reasonable, indicates that there are unknown predictors that warrant further exploration. Despite these limitations, our results contribute to identifying interventions that specifically target minimising miscommunications and interruptions, both of which are modifiable with the ultimate goal of improving NTS in surgery.

Conclusions

Our observational results suggest that effective communication and interruptions were consistent correlates of surgical teams’ NTS performance. Across teams, we observed examples of good and poor NTS performance. Nevertheless, these correlates of team performance are amenable to improvement or change. Implementation of interdisciplinary team training may contribute to improvements in NTS. However, such training programmes need to be underpinned by behaviour change frameworks that focus on sustained improvements in NTS performance. It is reasonable to propose that the behavioural indicators of success for overall performance are transferable across surgical specialties and can consequently, be developed.

Footnotes

Contributors: BMG conceived of the study, assisted in data analysis, interpreted results and drafted the manuscript. EH performed data analysis and assisted in interpretation. WC assisted in analysis and interpretation. EK, CS and NF assisted in recruitment and interpretation. All authors participated in the coordination of the study and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: BMG acknowledges the financial support of the Australian Research Council, Early Career Discovery Fellowship Scheme and the National Centre for Excellence in Nursing Research (NCREN).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Metro South Health Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Rogers SO Jr, Gawande AA, Kwaan M et al. . Analysis of surgical errors in closed malpractice claims at 4 liability insurers. Surgery 2006;140:25–33. 10.1016/j.surg.2006.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohn L, Corrigan J, Donaldson M. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington: National Academy Press, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazzocco K, Petitti DB, Fong KT et al. . Surgical team behaviors and patient outcomes. Am J Surg 2009;197:678–85. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kable AK, Gibberd RW, Spigelman AD. Adverse events in surgical patients in Australia. Int J Qual Health Care 2002;14:269–76. 10.1093/intqhc/14.4.269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raman J, Leveson N, Samost AL et al. . When a checklist is not enough: How to improve them and what else is needed. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016;152:585–92. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.JCAHO. Sentinel event data: root causes by event type (2004-second quarter 2011) . Secondary Sentinel event data: root causes by event type (2004-second quarter 2011) 2011. http://www.utmb.edu/emergency_plan/plan/appendix/jcaho/

- 7.Morgan L, Hadi M, Pickering S et al. . The effect of teamwork training on team performance and clinical outcome in elective orthopaedic surgery: a controlled interrupted time series study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006216 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillespie BM, Gwinner K, Chaboyer W et al. . Team communications in surgery—creating a culture of safety. J Interprof Care 2013;27:387–93. 10.3109/13561820.2013.784243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lingard L, Regehr G, Cartmill C et al. . Evaluation of a preoperative team briefing: a new communication routine results in improved clinical practice. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:475–82. 10.1136/bmjqs.2009.032326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang E, Massey D, Gillespie BM. Factors that influence the non-technical skills performance of scrub nurses: a prospective study. J Adv Nurs 2015;71:2846–57. 10.1111/jan.12743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillespie BM, Marshall AP, Gardiner T et al. . The impact of workflow on the use of the Surgical Safety Checklist: a qualitative study. ANZ J Surg 2016;86:864–7. 10.1111/ans.13433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutcliffe KM, Lewton E, Rosenthal MM. Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med 2004;79:186–97. 10.1097/00001888-200402000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Catchpole K. Task, team and technology integration in the paediatric cardiac operating room. Prog Pediatr Cardiol 2011;32:85–8. 10.1016/j.ppedcard.2011.10.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillespie BM, Chaboyer W, Fairweather N. Interruptions and miscommunications in surgery: an observational study. AORN J 2012;95:576–90. 10.1016/j.aorn.2012.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wahr JA, Prager RL, Abernathy JH III et al. , American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Patient safety in the cardiac operating room: human factors and teamwork: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2013;128:1139–69. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182a38efa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Healey AN, Primus CP, Koutantji M. Quantifying distraction and interruption in urological surgery. Qual Saf Health Care 2007;16:135–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sevdalis N, Healey AN, Vincent CA. Distracting communications in the operating theatre. J Eval Clin Pract 2007;13:390–4. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00712.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lingard L, Regehr G, Orser B et al. . Evaluation of a preoperative checklist and team briefing among surgeons, nurses, and anaesthesiologists to reduce failures in communication. Arch Surg 2008;143:12–17; discussion 18 10.1001/archsurg.2007.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halverson AL, Casey JT, Andersson J et al. . Communication failure in the operating room. Surgery 2011;149:305–10. 10.1016/j.surg.2010.07.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathieu JE, Heffner TS, Goodwin GF et al. . The influence of shared mental models on team process and performance. J Appl Psychol 2000;85:273–83. 10.1037/0021-9010.85.2.273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurmann A, Keller S, Tschan-Semmer F et al. . Impact of team familiarity in the operating room on surgical complications. World J Surg 2014;38:3047–52. 10.1007/s00268-014-2680-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ElBardissi AW, Duclos A, Rawn JD et al. . Cumulative team experience matters more than individual surgeon experience in cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013;145:328–33. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armitage-Chan EA. Human factors, non-technical skills, professionalism and flight safety: their roles in improving patient outcome. Vet Anaesth Analg 2014;41:221–3. 10.1111/vaa.12126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mesmer-Magnus JR, DeChurch LA. Information sharing and team performance: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol 2009;94:535–46. 10.1037/a0013773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sevdalis N, Davis R, Koutantji M et al. . Reliability of a revised NOTECHS scale for use in surgical teams. Am J Surg 2008;196:184–90. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.08.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gillespie BM, Chaboyer W, Fairweather N. Factors that influence the expected length of operation: results of a prospective study. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:3–12. 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lingard L, Regehr G, Espin S et al. . A theory-based instrument to evaluate team communication in the operating room: balancing measurement authenticity and reliability. Qual Saf Health Care 2006;15:422–6. 10.1136/qshc.2005.015388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Healey AN, Sevdalis N, Vincent CA. Measuring intra-operative interference from distraction and interruption observed in the operating theatre. Ergonomics 2006;49:589–604. 10.1080/00140130600568899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Polit D. Statistics and data analysis for nursing research. 2nd edn Upper Saddle River: Pearson, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Department of Biostatistics VU. Statistical Problems to Document and to Avoid. Secondary Statistical Problems to Document and to Avoid 2014. http://biostat.mc.vanderbilt.edu/wiki/Main/ManuscriptChecklist

- 31.Campbell G, Arfanis K, Smith AF. Distraction and interruption in anaesthetic practice. Br J Anaesth 2012;109:707–15. 10.1093/bja/aes219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gurses AP, Kim G, Martinez EA et al. . Identifying and categorising patient safety hazards in cardiovascular operating rooms using an interdisciplinary approach: a multisite study. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:810–18. 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siu J, Maran N, Paterson-Brown S. Observation of behavioural markers of nontechnical skills in the operating room and their relationship to intra-operative incidents. Surgeon 2016;14:119–28. 10.1016/j.surge.2014.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parker SH, Flin R, McKinley A et al. . Factors influencing surgeons’ intraoperative leadership: video analysis of unanticipated events in the operating room. World J Surg 2014;38:4–10. 10.1007/s00268-013-2241-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Healey AN, Undre S, Vincent CA. Developing observational measures of performance in surgical teams. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13(Suppl 1):i33–40. 10.1136/qshc.2004.009936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]