Abstract

Objective

A major preventable contributor to healthcare costs among older individuals is fall-related injury. We sought to validate a tool to stratify such risk based on readily available clinical data, including projected medication adverse effects, using state-wide medical claims data.

Design

Sociodemographic and clinical features were drawn from health claims paid in the state of Massachusetts for individuals aged 35–65 with a hospital admission for a period spanning January–December 2012. Previously developed logistic regression models of hospital readmission for fall-related injury were refit in a testing set including a randomly selected 70% of individuals, and examined in a training set comprised of the remaining 30%. Medications at admission were summarised based on reported adverse effect frequencies in published medication labelling.

Setting

The Massachusetts health system.

Participants

A total of 68 764 hospitalised individuals aged 35–65 years.

Primary Measures

Hospital readmission for fall-related injury defined by claims code.

Results

A total of 2052 individuals (3.0%) were hospitalised for fall-related injury within 90 days of discharge, and 3391 (4.9%) within 180 days. After recalibrating the model in a training data set comprised of 48 136 individuals (70%), model discrimination in the remaining 30% test set yielded an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.74 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.76). AUCs were similar across age decades (0.71 to 0.78) and sex (0.72 male, 0.76 female), and across most common diagnostic categories other than psychiatry. For individuals in the highest risk quartile, 11.4% experienced fall within 180 days versus 1.2% in the lowest risk quartile; 57.6% of falls occurred in the highest risk quartile.

Conclusions

This analysis of state-wide claims data demonstrates the feasibility of predicting fall-related injury requiring hospitalisation using readily available sociodemographic and clinical details. This translatable approach to stratification allows for identification of high-risk individuals in whom interventions are likely to be cost-effective.

Keywords: fall-related injury, adverse effects, risk stratification, prediction, precision medicine, health claims

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study includes a broad age range, spectrum of socioeconomic status and large and small hospitals, so results are likely to be highly generalisable.

The study uses health claims data to investigate a risk model derived in electronic medical records, suggesting the applicability of one data type to another.

While the study includes the entire state of Massachusetts, the extent to which it will generalise to other states and particularly other countries remains to be established.

Introduction

The cost of fall-related injury has been estimated at more than $30 billion annually in the USA,1 and such injuries have been targeted as a preventable contributor to costs particularly among older patients even as rates of fall appear to be increasing.2 While a range of interventions have been developed in an effort to reduce fall risk, many require specialised assessment or materials such that they would be too costly to deploy across all hospitalised individuals.3–9 As such, reduction of fall-related injury may require more stratified approaches in order to be cost-effective, but easily automated low-cost means of estimating risk do not yet exist.

In a previous report, using electronic health records from two academic medical centres, we demonstrated that a readily translatable regression model incorporating sociodemographic and clinical features available as artefacts of routine care could stratify fall risk following discharge.10 This stratification included an estimate of total medication side effects based on published medication labelling for side effect frequency.

A major obstacle to personalised medicine is that many risk models are published in a single cohort and never translated to practice. We therefore examined the features suggested to distinguish high-fall-risk individuals in state-wide data reflecting any Massachusetts residents hospitalised in 2012. Four key features of these data are, first, they span public and private insurance, second, they include all hospitals from small community facilities to large academic medical centres, third, they include all healthcare costs for residents regardless of where the care was received, including out of state and fourth, they are limited to features available in structured format to providers who submit insurance claims. Specifically, we examined the extent to which a model integrating data available at time of hospital discharge was predictive of subsequent fall risk across health systems and patient subpopulations.

Methods

Overall design

Data were drawn from the Massachusetts All-Payer Claims Database (APCD). This database encompasses all claims paid for every state resident independent of insurance type, including public and private payers.11 The index visit was defined as the first hospital discharge for individuals aged 35–65 between 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2012. That is, individuals enter the risk group following an initial discharge from the hospital. The age range was capped at age 65 (excluding 90 603 individuals) as the APCD is not integrated with Medicare; so complete data are not available for Medicare members. The study was allowed a waiver of informed consent under 45 CFR 46.116 as only de-identified data were used.

Outcomes and predictors

The primary study outcome was hospital admission for fall-related injury, defined in prior work as International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, (ICD-9) codes 800–847 (injuries including fracture, dislocation, strain and sprain), 850–854 (intracranial injury), 920–924 (contusion) or E-codes (external causes of injury) 880, 881, 884, 885 and 888 (accidental falls, excluding fall out of building, fall into hole or fall as a result of pushing by another). As such, in-hospital falls were not considered.

Predictors extracted from the APCD were those previously identified as contributing to fall risk prediction, including age, sex, self-reported race, insurance type (private, ie, commercial, insurance, vs public or no insurance), prior fall admission, presence of a psychiatric diagnosis and prescribed medications. Medications in APCD are not annotated to allow distinction between those prescribed at hospital discharge, or following hospital discharge. Therefore, any prescription filled within 15 days of hospital discharge was considered to be a probable discharge medication. For individuals with multiple admissions during the observation period, only the index admission was selected as previous analysis on data appropriate for nested models did not yield meaningfully different results.10

We incorporated age-adjusted Charlson Index as a summary measure of overall burden of illness.12 13 In addition, we incorporated a cumulative measure of medication adverse effects that could increase fall risk.10 This measure is the sum of the frequencies of side effects associated with increased risk for fall associated with each medication a patient is taking. These frequencies are drawn from the SIDER Side Effect Resource14 databases which maps medications to the frequency of individual side effects associated with those medications using drug labels and postmarketing surveillance data. A database query tool and database download instructions are available at http://sideeffects.embl.de. We provide a simple calculator for adverse effect burden at http://clearer.mghcedd.org. The Adverse Effect Burden Score represents an estimate of how likely a patient is to experience at least one side effect that may contribute to risk for fall (eg, gait instability or dizziness), based on the reported frequency of each adverse effect in medication labelling. The minimum score is 0 (no associated adverse effects) with no upper bound, with the assumption that adverse effect frequencies are additive. (So, eg, if two medications are each labelled as being associated with dizziness in 10% of patients, a patient treated with both would have an Adverse Effect Score of 0.2; if one medication also had a 5% frequency of unsteady gait, fall risk would increase to 0.25.) Of note, in prior work, narrower manually curated measures of adverse effect liability, such as the Anticholinergic Risk Scale Score,15 did not improve model fit whereas adverse effect burden did improve fit, so only Adverse Effect Burden Score is incorporated here.

Analysis

As the goal of the study was to predict readmission for fall-related injury in a given interval based on multiple predictors available, rather than to estimate instantaneous hazard, the above data were modelled using multivariable logistic regression. Given the size of the cohort, hold-out validation was used to assess generalisability; as such, the full cohort was split randomly into a training set, including 70% of the cohort, and a testing set including 30% of the cohort, preserving overall event rate in each cohort but otherwise without stratification. Except where noted, all results refer to the testing set in order to minimise risk of overfitting; the baseline model was specified a priori based on preliminary work.10

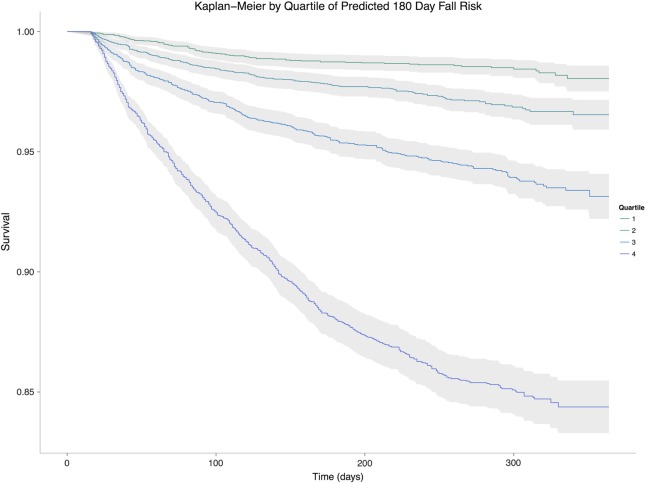

First, the predictors previously identified were used to estimate a 6-month model in the training set. The discrimination of this model was evaluated in the held-out test set. As an illustration of test set model calibration, Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated for each quartile of predicted fall risk. Next, model performance was evaluated in subgroups—tranches of age, sex, hospital size and primary index admission diagnosis—of the training set as a means of examining generalisability across patient and clinical contexts. Finally, the above steps were repeated to produce another model of falls within 90 days, recognising that shorter term fall risk may be more amenable to intervention. This alternative model also serves as a sensitivity analysis of the modelling methodology. (To facilitate investigation in non-US cohorts, we also fit 180-day models excluding insurance type, presented in online supplementary table S1).

bmjopen-2016-012189supp_table1.pdf (138.2KB, pdf)

As patient medications were based on pharmacy claims made within 15 days of hospital discharge, events within the first 15 days were excluded (n=4308) because of the possibility that the prescription followed rather than preceded the fall. Admissions followed by a fall or at least the requisite 180 days of follow-up during the observation period were included in the analysis. The 180-day threshold was selected a priori for consistency with prior work, recognising that short-term fall (ie, within 30 days) may require alternate models. Analyses were performed using R 3.2.2 (http://www.r-project.org).

Patient involvement

The focus on an outcome of substantial relevance to patients was motivated by review of healthcare outcomes contributing to morbidity as well as informal discussion with patients and carers regarding their priorities and experiences following hospital discharge. Patients and carers were not involved in study design per se. Study results will be disseminated through the authors’ website and Partners HealthCare patient newsletters.

Results

The cohort as a whole included 68 764 individuals aged 35–65 with an index hospitalisation in 2012 who had either event or adequate follow-up to observe lack of an event; characteristics are summarised in table 1, with unadjusted comparisons in online supplementary table S2. Among them, 2052 (3.0%) were readmitted for fall-related injury within 90 days, and 3391 (4.9%) within 180 days. The training cohort included 48 136 (70.0%) and the held-out testing cohort included 20 628 (30.0%) individuals.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical features of the Massachusetts (MA) hospitalisation cohort

| MA hospitalisation cohort (N=68 764) | With fall-related injury (N=3391) | Without fall-related injury (N=65 373) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Men | 31 310 (45.5) | 1610 (47.5) | 29 700 (45.4) |

| White | 17 372 (25.3) | 1331 (39.3) | 16 041 (24.5) |

| Private insurance | 28 737 (41.8) | 2539 (74.9) | 26 198 (40.1) |

| Index admission | |||

| Via emergency room | 27 437 (39.9) | 1916 (56.5) | 25 521 (39.0) |

| Primary psychiatric | 6881 (10.0) | 486 (14.3) | 6395 (9.8) |

| Hospital size: | |||

| Small | 7823 (13.0) | 467 (14.6) | 7356 (12.9) |

| Medium | 28 583 (47.6) | 1385 (43.3) | 27 198 (47.9) |

| Large | 23 635 (39.4) | 1350 (42.2) | 22 285 (39.2) |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Age at index admission (years) | 51.59 (8.71) | 52.75 (8.01) | 51.53 (8.74) |

| Total medications prescribed at discharge | 3.32 (3.43) | 4.47 (4.46) | 3.26 (3.36) |

| Age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index | 4.83 (8.22) | 11.84 (11.82) | 4.47 (7.82) |

| Medication Adverse Effect Burden Score | 1.01 (1.57) | 1.57 (2.12) | 0.98 (1.53) |

bmjopen-2016-012189supp_table2.pdf (255.5KB, pdf)

The logistic regression model predicting 180-day readmission is shown in table 2; features associated with significantly increased risk (p<0.001) included greater age, private insurance, index admission via emergency department, index admission with a primary psychiatric diagnosis and overall Adverse Effect Burden Score from medication side effects.

Table 2.

Logistic regression model for prediction of fall within 180 days of hospital discharge, training data set

| Variable | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Medication Adverse Effect Burden Score | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.09) |

| Age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.05 (1.04 to 1.05) |

| White | 1.11 (1.01 to 1.22) |

| Male | 1.02 (0.94 to 1.12) |

| Private insurance | 2.50 (2.22 to 2.81) |

| Age at admission (years) | 1.01 (1.01 to 1.02) |

| Total number of medications | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.02) |

| Primary psychiatric diagnosis at admission | 1.27 (1.11 to 1.45) |

| Admission via emergency department | 1.24 (1.13 to 1.35) |

For each 0.1-point increment in medication burden (corresponding to a single adverse effect with 10% frequency), odds of fall increased by 0.6%. In the testing cohort, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) was 0.74 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.76). Figure 1 illustrates time to readmission for fall-related injury by quartile of predicted fall risk in the testing set. Among those in the highest risk group, 11.4% experienced fall-related injury within 180 days, compared with 1.2% in the lowest risk group. In all, 586 out of 1018 falls (57.6%) occurred in the highest risk quartile, and 839 out of 1018 (82.4%) falls occurred in the two higher risk quartiles. (For illustrative purposes online supplementary table S3 reports the medications contributing the greatest absolute risk and their frequency of use).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve depicting time to hospital admission for fall-related injury following index hospital discharge, by risk quartile in testing data set for 180-day fall.

bmjopen-2016-012189supp_table3.pdf (175.9KB, pdf)

In order to assess the generalisability of this model, we examined model performance in subsets of the testing set. Table 3 shows resulting AUC in the full cohort (see online supplementary figure 1a) and subgroups defined by sex (see online supplementary figure 1b), age (see online supplemental figure 1c), primary admission diagnosis index (see online supplemental figure 1d) and hospital size (see online supplemental figure 1e).

Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis examining area under receiver operating characteristic curve in testing data set for clinical subgroups

| 180d model | 90d model | |

|---|---|---|

| Full cohort | 0.74 | 0.72 |

| Sex | ||

| Males | 0.72 | 0.70 |

| Females | 0.76 | 0.74 |

| Age | ||

| 35–45 | 0.78 | 0.75 |

| 45–55 | 0.73 | 0.71 |

| 55–65 | 0.71 | 0.70 |

| Prior hospitalisation | ||

| Pulmonary | 0.75 | 0.72 |

| Musculoskeletal | 0.73 | 0.70 |

| Psychiatric | 0.69 | 0.69 |

| Gastrointestinal | 0.78 | 0.76 |

| Circulatory | 0.68 | 0.70 |

| Discharge hospital size: | ||

| <2000 admissions | 0.66 | 0.66 |

| 2000–9000 admissions | 0.76 | 0.76 |

| >9000 admissions | 0.74 | 0.71 |

Area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) <0.70 indicated in italics.

bmjopen-2016-012189supp_figures.pdf (855.4KB, pdf)

Of note, the model performed best in hospitals with at least 2000 admissions per year (AUC of 0.76 or 0.74 vs 0.66), and in admissions for gastrointestinal and pulmonary diagnoses (AUC of 0.78 and 0.75 vs 0.68 for circulatory and 0.69 for psychiatric disorders).

As a sensitivity analysis and extension to nearer term fall, we refit another regression model in the training set with the same predictors but instead used 90-day fall as the outcome; coefficients for the model are shown in table 4.

Table 4.

Logistic regression model for prediction of fall within 90 days of hospital discharge, training data set

| Variable | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Medication Adverse Effect Burden Score | 1.06 (1.02 to 1.10) |

| Age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.04 (1.03 to 1.04) |

| White | 1.04 (0.92 to 1.17) |

| Male | 1.00 (0.90 to 1.12) |

| Private insurance | 2.59 (2.24 to 3.00) |

| Age at admission (years) | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.02) |

| Total number of medications at discharge | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.02) |

| Primary psychiatric diagnosis at admission | 1.19 (1.00 to 1.41) |

| Admission via emergency department | 1.26 (1.12 to 1.41) |

In the testing data set, the AUC of the 90-day model was 0.72 (95% CI 0.70 to 0.74). Once again, model performance was characterised in patient subgroups with similar results to those observed for longer term prediction (table 3, right column); AUC curves are illustrated for the full cohort (see online supplementary figure 2a) and subgroups defined by sex (see online supplementary figure 2b), age (see online supplementary figure 2c), Primary Admission Diagnosis Index (see online supplementary figure 2d) and hospital size (see online supplementary figure 2e). Of 612 falls, 343 (56.0%) occurred in the highest risk quartile, and 497 (81.2%) occurred in the two higher risk quartiles. Online supplementary figure S3 shows time to readmission for fall-related injury by risk quartile, ranging from 0.9% in the lowest to 6.7% in the highest risk quartile.

Discussion

These results demonstrate the ability of a simple regression model based on readily available patient-level clinical features to stratify fall risk in a state-wide data set. Based on the observed discrimination and calibration, if the aim is to accurately predict fall in a given individual, further diagnostic testing is likely required. But as a means of targeting interventions to high-risk groups, the risk estimates appear promising particularly as they are derived from coded clinical data available at discharge. In this context, calibration may be as important as discrimination16 in evaluating a prediction tool. Here, more than 82% of postdischarge falls within 180 days in an independent testing cohort occurred in the two higher risk quartiles.

The findings substantially extend a previous report that introduced the notion of an aggregate adverse effect measure, the Medication Adverse Effect Burden Score. Here, the risk model is shown to perform similarly in a different data type (ie, claims data); to maintain discrimination across hospitals with at least 2000 admissions, diagnostic category and patient subgroup, despite some variation in model performance; and in particular to perform well among younger patients despite substantially lower event rates.10

The fall risk score complements other, more specific associations between individual medications and fall liability.17 The assignment of adverse effect burden across the medication list as a whole allows a more personalised approach to modelling expected adversity due to medications. This is important in two regards. First, this score and the medications which drive it can be the subject of future optimisation research. Whereas studies implicating individual drugs quantise an inherently continuous risk, that is, take higher and lower risk drugs in isolation and instead create list of risk and no risk drugs, the overall adverse effect burden could be optimised with respect to a range of clinically appropriate treatments and adverse events of particular concern in this patient in a more realistic model of additive adverse effect burden. Second, with the proliferation of electronic health records and the increased visibility of personalised medicine, this approach draws attention to a no less important possibility of personalised harm reduction.

Widespread availability of medical data in digital form will facilitate discovery of numerous predictive tools, but the pathway from research in computer science back to the bedside is unclear. The choice to make the best possible model regardless of implementation complexity may be a viable strategy for machine learning; however, this strategy should not be a foregone conclusion. The model reported here is not complex and as such has a relatively straightforward path for translation into practice. This translation would constitute a substantive personalisation of medicine that stands to benefit patients by facilitating targeted interventions, be they fall risk mitigation given a fixed expected risk or medication optimisation to reduce expected risk directly.

Several caveats bear consideration. First, while the cohort examined here is a large one, it will be important to examine other clinical data sets drawn from other regions or countries where risk factors may vary. Confidence in the portability of this model is increased by its consistency across patient subgroups, but further estimates of generalisability will be useful. Understanding the extent to which shorter term falls (ie, within 30 days) require alternate means of prediction will also be valuable, but requires data sets with greater resolution regarding discharge prescriptions. Second, we excluded older individuals as they are not consistently included in the APCD data set, which excludes Medicare data; further investigation in that population will be valuable as fall risk increases with age. If anything, we expect that exclusion of the highest risk individuals should bias us towards more conservative estimates of model performance. Third, the model captures only injuries requiring hospitalisation commonly ascribed to falls, and thus may not be sensitive to all fall-related injuries. Finally, we noted that model performance was poorer (although AUC still exceeded 0.68 consistently) among specific diagnostic populations, including cardiovascular and psychiatric cohorts. This may arise in part because presence of psychiatric illness itself is a contributor to fall risk among medical populations,10 and the model therefore does not benefit from this term when the population is limited to those with a primary diagnosis. In the case of cardiovascular disease, specific medications may exert disproportionate effects or interact with specific diagnosis.17 These disorders may also impact access care when falls do occur. The model also performed somewhat less well in hospitals with fewer than 2000 admissions, suggesting the utility of further refinement and study in that setting.

It should be emphasised that analysis of routine clinical data represents only a starting point for prediction. It is likely that more targeted assessments—for example, of balance and gait,18 vision19 and home environment—or more detailed longitudinal monitoring20 would also help to identify those at greatest risk for falls. As such, two forms of next-step investigation will be particularly valuable. First, comparing clinical risk score alone with augmented risk score in terms of discrimination could be useful in determining the incremental benefit of targeted assessment. Considering different fall types and contexts may be helpful in this regard. Second, with the ability to stratify risk reliably, intervention trials in high-risk populations could be pursued. In addition to interventions with established efficacy such as strength and balance training,7–9 21 these trials might include efforts to reduce medication-associated risk at time of discharge, a small but consistent and potentially modifiable contributor to fall hazard.10 17 Importantly, the decision about when a model is good enough for clinical application depends on the context and the intervention contemplated, not on any particular area under the ROC curve or other quantitative measure.22

Taken together with a prior report demonstrating model portability within academic medical centres, these results suggest the feasibility of applying a risk stratification tool to predict readmission for fall-related injury across clinical settings and patient populations. With further validation, risk models based on large-scale electronic health data may provide a viable means of moving towards a more personalised medicine.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the staff of Massachusetts Center for Health Information and Analysis (CHIA) for their support with the APCD data set.

Footnotes

Contributors: THMJ helped design the study, analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. VMC and AC imported and cleaned the data and generated all derived variables. AMR contributed to preparation of the manuscript. RHP initiated the project, designed the study, monitored the analyses, created the tool for risk stratification and drafted the manuscript. He is a guarantor.

Funding: This work was supported in part by 1P50MH106933 from NIMH and NHGRI, and by 1R01HL124262-01A1 from NHLBI.

Competing interests: All authors will complete the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that: THMJ, VMC, AC and AMR have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare that we have no competing interests. RHP has read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declares the following interests: RHP has served on advisory boards or provided consulting to Genomind, Healthrageous, Pamlab, Perfect Health, Pfizer, Psybrain and RIDVentures.

Ethics approval: This study obtained IRB approval from the Partners Human Research Committee under protocol number 2012-P-002527, and from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health under protocol number 533160-1. No informed consent was required, as this project is a retrospective healthcare usage/clinical study involving thousands of patients and multiple years of data—that is, consent could not feasibly be obtained from all subjects.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Stevens JA, Corso PS, Finkelstein EA et al. . The costs of fatal and non-fatal falls among older adults. Inj Prev 2006;12:290–5. 10.1136/ip.2005.011015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartholt KA, van Beeck EF, Polinder S et al. . Societal consequences of falls in the older population: injuries, healthcare costs, and long-term reduced quality of life. J Trauma 2011;71:748–53. 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181f6f5e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nyström A, Hellström K. Fall risk six weeks from onset of stroke and the ability of the prediction of falls in rehabilitation settings tool and motor function to predict falls. Clin Rehabil 2013;27:473–9. 10.1177/0269215512464703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baetens T, De Kegel A, Calders P et al. . Prediction of falling among stroke patients in rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med 2011;43:876–83. 10.2340/16501977-0873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryan JJ, McCloy C, Rundquist P et al. . Fall risk assessment among older adults with mild Alzheimer disease. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2011;34:19–27. 10.1519/JPT.0b013e31820aa829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.da Costa BR, Rutjes AW, Mendy A et al. . Can falls risk prediction tools correctly identify fall-prone elderly rehabilitation inpatients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e41061 10.1371/journal.pone.0041061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emilio EJ, Hita-Contreras F, Jiménez-Lara PM et al. . The association of flexibility, balance, and lumbar strength with balance ability: risk of falls in older adults. J Sports Sci Med 2014;13:349–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clemson L, Fiatarone Singh MA, Bundy A et al. . Integration of balance and strength training into daily life activity to reduce rate of falls in older people (the LiFE study): randomised parallel trial. BMJ 2012;345:e4547 10.1136/bmj.e4547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liston MB, Alushi L, Bamiou DE et al. . Feasibility and effect of supplementing a modified OTAGO intervention with multisensory balance exercises in older people who fall: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2014;28:784–93. 10.1177/0269215514521042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castro VM, McCoy TH, Cagan A et al. . Stratification of risk for hospital admissions for injury related to fall: cohort study. BMJ 2014;349:g5863 10.1136/bmj.g5863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Massachusetts All Payer Claims Database. Secondary Massachusetts All Payer Claims Database. http://www.chiamass.gov/ma-apcd/

- 12.Perlis RH, Iosifescu DV, Castro VM et al. . Using electronic medical records to enable large-scale studies in psychiatry: treatment resistant depression as a model. Psychol Med 2012;42:41–50. 10.1017/S0033291711000997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clements CC, Castro VM, Blumenthal SR et al. . Prenatal antidepressant exposure is associated with risk for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder but not autism spectrum disorder in a large health system. Mol Psychiatry 2015;20:727–34. 10.1038/mp.2014.90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campillos M, Kuhn M, Gavin AC et al. . Drug target identification using side-effect similarity. Science 2008;321:263–6. 10.1126/science.1158140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudolph JL, Salow MJ, Angelini MC et al. . The anticholinergic risk scale and anticholinergic adverse effects in older persons. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:508–13. 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook NR. Use and misuse of the receiver operating characteristic curve in risk prediction. Circulation 2007;115:928–35. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.672402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tinetti ME, Han L, Lee DSH et al. . Antihypertensive medications and serious fall injuries in a nationally representative sample of older adults. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:588–95. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robertson MC, Gillespie LD. Fall prevention in community-dwelling older adults. JAMA 2013;309:1406–7. 10.1001/jama.2013.3130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pineles SL, Repka MX, Yu F et al. . Risk of musculoskeletal injuries, fractures, and falls in medicare beneficiaries with disorders of binocular vision. JAMA Ophthalmol 2015;133:60–5. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.3941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaudhuri S, Thompson H, Demiris G. Fall detection devices and their use with older adults: a systematic review. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2014;37:178–96. 10.1519/JPT.0b013e3182abe779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dykes PC, Carroll DL, Hurley A et al. . Fall prevention in acute care hospitals: a randomized trial. JAMA 2010;304:1912–18. 10.1001/jama.2010.1567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perlis R. Translating biomarkers to clinical practice. Mol Psychiatry 2011;16:1076–87. 10.1038/mp.2011.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012189supp_table1.pdf (138.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012189supp_table2.pdf (255.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012189supp_table3.pdf (175.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012189supp_figures.pdf (855.4KB, pdf)