Abstract

Introduction

Older adults frequently fall after discharge from hospital. Older people may have low self-perceived risk of falls and poor knowledge about falls prevention. The primary aim of the study is to evaluate the effect of providing tailored falls prevention education in addition to usual care on falls rates in older people after discharge from hospital compared to providing a social intervention in addition to usual care.

Methods and analyses

The ‘Back to My Best’ study is a multisite, single blind, parallel-group randomised controlled trial with blinded outcome assessment and intention-to-treat analysis, adhering to CONSORT guidelines. Patients (n=390) (aged 60 years or older; score more than 7/10 on the Abbreviated Mental Test Score; discharged to community settings) from aged care rehabilitation wards in three hospitals will be recruited and randomly assigned to one of two groups. Participants allocated to the control group shall receive usual care plus a social visit. Participants allocated to the experimental group shall receive usual care and a falls prevention programme incorporating a video, workbook and individualised follow-up from an expert health professional to foster capability and motivation to engage in falls prevention strategies. The primary outcome is falls rates in the first 6 months after discharge, analysed using negative binomial regression with adjustment for participant's length of observation in the study. Secondary outcomes are injurious falls rates, the proportion of people who become fallers, functional status and health-related quality of life. Healthcare resource use will be captured from four sources for 6 months after discharge. The study is powered to detect a 30% relative reduction in the rate of falls (negative binomial incidence ratio 0.70) for a control rate of 0.80 falls per person over 6 months.

Ethics and dissemination

Results will be presented in peer-reviewed journals and at conferences worldwide. This study is approved by hospital and university Human Research Ethics Committees.

Trial registration number

Keywords: GERIATRIC MEDICINE, PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study will be conducted at three hospital sites that provide services for a broad range of older people being discharged to the community.

A process evaluation will be conducted alongside the main trial to aid in understanding how the patient education programme influences engagement in falls prevention strategies after discharge.

Unanticipated changes to local healthcare services may affect participation in the trial or follow-up procedures after discharge.

Background

Population ageing is a growing challenge for healthcare systems worldwide.1 Advanced age is accompanied by an increased risk of falls,2 3 which are associated with physical injury, loss of independence and reduced health-related quality of life.4–8 Falls are also the leading cause of injuries that result in older people being admitted to hospital.9 After hospital discharge, falls rates are increased compared to community dwelling populations10–13 and there is a high risk of other adverse events.14 Older adults have over twice the risk of sustaining a hip fracture after hospitalisation, especially in the month after discharge,15 and around one-third experience functional decline compared to their preadmission level of activities of daily living.16 17

When older people transition from the hospital to the community, there is a transfer in responsibility for healthcare from the inpatient team to the person and their community healthcare team and patients can be encouraged to take an active role in this transition.18 19 However, a large observational study found patients to have low levels of knowledge about how to reduce their falls risk and low levels of engagement in suitable exercise programmes.20 21 Risk-taking behaviour in this population is also common, as a result of older people wanting to remain independent and having difficulty recognising and compensating for their physical limitations.22 Further, recent observational research has identified that both patients and health professionals rarely initiate conversations about falls during the postdischarge period, with each feeling that the other group will tell them if there is a problem.23 Hence, there appears to be need for a structured education programme to empower older adults to actively manage the risk of falls that they face following discharge from hospital.

Little data exist to show whether pedagogically sound education for older people discharged to the community reduces fall rates. Previous recommendations that well-designed falls prevention education be provided to older people24 25 have not been based on data derived from the postdischarge older adult population. However, a recent systematic review of falls prevention studies (14 studies) that contained patient education, either alone or part of a multifactorial intervention, found that the interventions were effective in reducing fall rates among hospital inpatients and postdischarge populations (risk ratio (RR) 0.77, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.87).26 A recent trial demonstrated that a strength and balance training programme can increase the rate of falls in the postdischarge population,27 even though it is a key falls prevention measure in otherwise community-dwelling older adults. This finding suggests that direct extrapolation of community focused falls prevention interventions may not be safe for this population. Similarly, intensive inpatient education based on the health-belief model and focused on the prevention of falls in hospitals has been demonstrated to be one of the few successful falls prevention interventions for the inpatient setting.28 However, there has been no carry-over effect of this approach into the postdischarge period identified when investigated,12 most likely due to its in-hospital focus.

To meet this gap, we have designed and piloted an innovative tailored falls prevention education intervention that uses behaviour change theory.29 30 It targets older people being discharged from hospital and is designed to reduce falls and improve function after discharge. We conducted a successful pilot trial of this education programme showing reduced falls after hospital discharge.29 We will now conduct a randomised controlled trial with the aim of determining whether this tailored education, reinforced by a health professional in hospital and after discharge, reduces rates of falls in older people living at home after hospital discharge.

The current study shall test the primary hypothesis that providing tailored falls prevention education that includes the provision of multimedia materials as well as individual health professional consultations and reinforcement in hospital and after discharge, in addition to usual care, reduces falls rates in older people after discharge from hospital compared to providing a social intervention in addition to usual care. The secondary hypotheses are that the tailored education programme will (1) reduce injurious falls rates; (2) decrease the proportion of people who become fallers during the trial period; (3) improve functional ability as measured by activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL); (4) improve health-related quality of life (HRQoL); and will be more cost-effective compared to usual care.

We shall carefully analyse the different elements of our multimodal falls prevention programme by conducting a separate process evaluation and identify aspects that particularly contribute to effectiveness and feasibility. In addition to effectiveness outcomes and the process evaluation, we will record healthcare resource usage information and trial intervention costs for use in a subsequent trial-based economic evaluation (the details of which will be reported separately).

Methods

Design

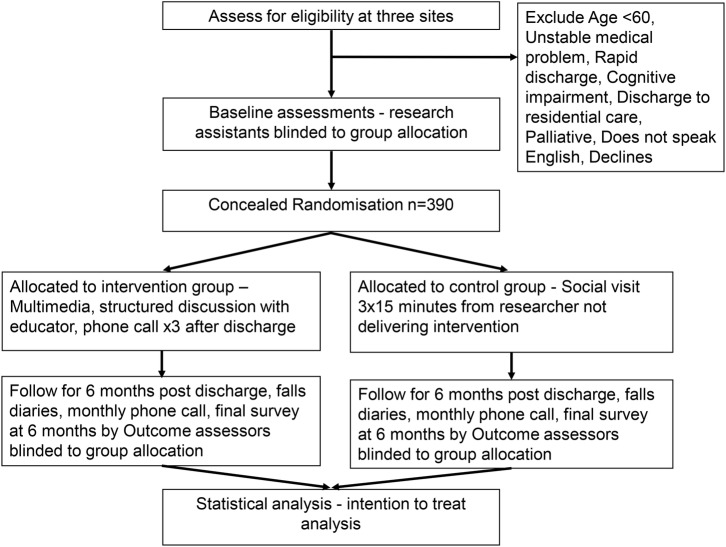

Multisite RCT (n=390), adhering to Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines31: Assess for eligibility, followed by concealed randomisation; blinded baseline and outcome assessors, intention-to-treat analysis and two group parallel design (see figure 1). The protocol is reported in accordance with the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) 2013 Statement32 (see online supplementary additional file 1).

Figure 1.

Participant flow through the study.

bmjopen-2016-013931supp.pdf (60.7KB, pdf)

Alongside the main analysis of quantitative outcomes from the trial, we shall conduct a mixed methods process evaluation. The protocol for the process evaluation will be published separately.

Ethical considerations

All participants will provide written informed consent to participate in the trial. Any amendments to the study will be agreed on by the trial management committee and submitted to all ethics committees for approval prior to being started.

Participants

The population of interest is older people who are to be discharged after a hospital stay of longer than ∼5 days. Only patients who are to be discharged to the community will be included in our sample, as those patients who are discharged to supported accommodation are unable to engage in the decision-making that this education package will suggest. Additionally, research meta-analyses demonstrate that falls in supported accommodation require different interventions to those in the community.33 Since telephone follow-up is essential to the education intervention and measurement of the primary outcomes, participants who have sensory impairments which mean they are unable to engage with the educator to undertake coaching through telephone calls will be excluded from the study.

Inclusion criteria

Patient 60 years of age or older, Abbreviated Mental Test Score >7/10,34 admitted to participating wards for this trial, discharged to the community, provides written consent to participate in the study, not previously enrolled in the study, able to understand English sufficiently to take part in the education and receive telephone calls.

Exclusion criteria

Unstable medical problem, discharged to transitional or residential care, requiring palliative care, short stay admissions that preclude screening, enrolment and intervention during the admission (defined as admission planned of <5 days).

Settings

Three rehabilitation wards located in Midland, Bentley and Armadale hospitals in Australia. These contain ∼100 rehabilitation beds (Bentley n=36 beds, Armadale n=40, Midland n=24) in total which manage geriatric rehabilitation for orthopaedic and neurological conditions and general functional decline, including patients with a primary diagnosis of stroke and postsurgical rehabilitation. Older patients admitted to these wards are almost exclusively over 65 years of age. The three settings provide comprehensive geriatric multidisciplinary care with after-hours support. Allied health services including physiotherapy and occupational therapy are provided each weekday, with weekend therapy cover provided in both wards for patients with acute medical requirements.

Older patients with complex mental health conditions that are the primary cause of admission are not managed on the rehabilitation units but admitted to a separate mental health unit. Older patients who undergo surgical procedures are admitted to surgical wards. All these wards are excluded from the recruitment procedure.

Randomisation and blinding

Participants will be allocated to groups in a 1:1 ratio in consecutive order after enrolment by the research assistant. Randomisation will be determined by a computer generated random number sequence that will be produced by a research collaborator from another state, who is not involved in recruitment, intervention delivery or data collection. The sequence is then placed in sealed, opaque, consecutively numbered envelopes. These envelopes are held securely at another University in a location that is not accessible by any on the trial team. Research assistants notify the educator when a participant is enrolled and the educator telephones the University to be given the participant's allocation. If the participant is allocated to the control group, the educator will inform the health professional who delivers the social intervention.

The investigators on the trial team will be blinded to group allocation. Research assistants who enrol patients and conduct baseline assessments are blinded to the group allocation throughout the study. The outcome assessor who conducts monthly phone calls to collect falls outcome data and postdischarge surveys will be blinded to group allocation. The educators are not involved in baseline data collection or telephone data collection. Hospital staff who organise discharge services remain blinded to participants’ enrolment into the study. Blinding will be tested in the final month of the study for the research assistants and forward staff. Only the health professionals who deliver the intervention or social programme to the control group will know the patients group allocation. Participants cannot be blinded to receiving the intervention but will not be specifically informed whether the intervention they receive is as part of the control group or the intervention group. Participants will be reminded at enrolment, discharge and during monthly phone calls not to divulge their allocation to hospital staff, research staff or other patients and, in particular, not to discuss their intervention with other patients.

Intervention

The overview of the intervention is presented in table 1 using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist.35

Table 1.

Overview of the education intervention*

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Brief name | ‘Back to my Best’—Individualised multimodal education programme with trained health professional follow-up. |

| 2. Why | The framework of the programme has been designed based on evidence from previous falls prevention education trials.12 20 21 23 28 29 The design and delivery also uses concepts of adult learning and behaviour change theory.30 36–38 The programme will facilitate participant behaviour change and build motivation and capability. It will assist participants to undertake goal setting, and develop a practical plan of action.29 |

| 3. What—materials | A pre-made video of 10 min is shown to participants. It depicts two older adults in a real-life setting of their own home and is viewed on a handheld digital video player for ease of access. It is accompanied by a workbook which is printed in high-quality black/white with colour pictures to assist with comprehension, room for writing and in a large print, easy read format. A facilitator workbook and fidelity checklist will be used to deliver the intervention. |

| 4. What—procedures | Participants are shown the video and issued with the workbook to read. The educator reviews the information presented with the participant by structuring the topics that are covered in the education as outlined: Module 1: Epidemiology of falls and functional decline after discharge, Development of awareness of personal risk of falls. Module 2: Self-assessment of falls risk to guide the plan and feedback of the therapist. Module 3: Develop a plan for undertaking required ADL and IADL when discharged, engaging in exercise and return to usual activity. Module 4: Identify possible barriers to plan, reinforcement and motivation. |

| 5. Who—provided | Physiotherapists with a clinical background in rehabilitation and geriatrics and experienced at working in a hospital setting. |

| 6. How | Education is delivered face to face in hospital by the participants’ bedside and through phone calls after hospital discharge. |

| 7. Where | The education will be delivered in rehabilitation wards of Western Australian hospitals and to participants’ homes by telephone. |

| 8. When and how much | In hospital—participants will ideally each have at least 2 sessions of education; the estimated time is ∼45 min of education. The aim is for between 2 and 4 sessions to be delivered and each session is designed to last ∼15 min, but this can be varied at the educator's discretion according to participants’ needs. After discharge—the educator makes 3 phone calls, 1 each month for 3 consecutive months after discharge. Each call may last up to 15 min with time varying according to discussion of plan, with the estimated time being ∼30 min for total telephone contact. |

| 9. Tailoring | All participants will receive the same workbook content and view the video and discuss the four modules as part of the education. However, relevant aspects of the education will be tailored according to participants’ feedback during formative discussions. The educator will personalise the information provided, so it is relevant for that participant and develop an appropriate action plan which is designed to meet the participant's circumstances after discharge. |

| 10. Modifications | Modifications to the intervention will be reported. |

| 11. How well (planned) | The educators receive training at baseline in delivering the intervention by a therapist trained in delivering falls prevention education previously. An educator workbook with protocol and checklists for each module will be used by educators to deliver the intervention. |

| 12. How well (actual) | Intervention delivery and the extent to which the intervention was delivered as planned will be reported. |

*Presented using the TIDieR checklist35

TIDieR, Template for Intervention Description and Replication

The intervention is based on pedagogically sound processes of adult learning principles.34 The educator aims to foster the participants’ motivation to learn, highlight personal relevance with the messages presented, draw on relevant prior experience and facilitate participation and interaction during the education sessions.36 It is also adapted as recommended for low functional health literacy.39 The digital video and workbook are designed to contain identical content, which depicts an older person as the patient model. The content is based on the principles of health behaviour change for understanding health-related behaviours.37–38 These conceptualise that capability, opportunity and motivation interact to generate the desired behaviour; that is, engagement in falls prevention strategies and safe resumption of ADL and IADL. Capability includes having the necessary knowledge about falls prevention and skills to engage in the desired health behaviours. Motivation energises and directs behaviour, including goals and conscious decision-making. Opportunity includes all factors that lie outside the individual that prompt or make the behaviour possible.30 Messages include recommendations (which can be tailored for each participant) to seek assistance if required for home tasks or personal care, instructions on how to engage in exercise at a suitable level for their function, to modify home or aids if required, to use their walking aid and to return to usual activities gradually. Inclusion of multimedia information delivery has previously been shown to enhance patient falls prevention knowledge and motivation to participate in falls prevention activities compared to provision of written materials alone.40

Participants will receive the falls prevention education by the educator in a one-to-one interaction by their bedside. Other staff or patients are not present during education sessions. The educator facilitates optimal engagement with the education by adjusting environmental or individual elements, including seated position and application of visual or hearing aids and checking that the participant is feeling alert and comfortably ready to engage in an education session. Participants are asked not to reveal their allocation to the assessors either at discharge or during phone calls, or to discuss their intervention with other patients.

Once per month for 3 months after participants leave hospital, those participants in the intervention group receive a coaching telephone call from the educator, which uses active learning principles and health behaviour change principles,30 36 37 to reinforce and personalise the contents of the education for the participant.

Control conditions

The control group will receive between one and three (total estimated time of 45 min) sessions with a trained health professional person who will discuss aspects of positive ageing with participants in the control group, using a scripted programme. The session will be led by the health professional and will not give any specific falls prevention information to the participant.

Usual care

All participants in the intervention and control groups will receive the education or social intervention in addition to usual care. Local falls prevention programmes operate on all wards and staff receive falls prevention education as part of regular staff training programmes. Patients receive falls prevention education as part of usual medical care; this is provided during the inpatient stay by allied health, medical and nursing staff and is ongoing to the patient's individual medical requirements. Discharge programmes at all three sites are provided as required for patients and include home visiting by healthcare workers, home assistance and ongoing outpatient rehabilitation. In addition, diagnostic specific falls prevention measures and other relevant health information is provided for patients and their families by means of brochures and self-help guides on the ward foyer and outpatients’ area. The intervention gives participants capability and motivation to engage with usual care processes that are relevant to their circumstances and initiate their own actions. For example, the educator can discuss with a participant the rationale for a home visit by an occupational therapist and encourage the participant to engage with the therapist and accept the recommended therapy interventions.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measure

Rate of falls in the first 6 months after discharge

The definition of a fall event will be the WHO definition, namely: “an event which results in a person coming to rest inadvertently on the ground or floor or other lower level”.41

Secondary outcome measures

Proportion of participants who sustain one or more falls during the 6 months after discharge

Rate of injurious falls in the first 6 months after discharge

Definition of injurious falls

Falls will be classified as injurious if they result in bruising, laceration, dislocation, fracture, loss of consciousness or patient report of persistent pain which is consistent with previous work in this field.28 42 43 This classification will be determined by the research assistant who collects the falls data and who will be blinded to group allocation of the participants.

Falls outcomes will be measured in two ways. First, a falls diary will be issued to participants at discharge. The research assistant explains the definition of a fall as described above and asks participants to record any fall in their diary. Second, the research assistant calls each participant once per month for 6 months after discharge and asks about falls events using the recommended questioning method: ‘‘In the past month, have you had any fall including a slip or trip in which you lost your balance and landed on the floor or ground or lower level?’’44 At this time, participants are also asked to check their diary and to recall any events in the past month as monthly recall has been shown to improve accuracy of recall of falls events by older people.44

Participants’ level of functional ability (with ADL and IADL) measured at baseline, discharge and 6 months after discharge, using the Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living45 and the Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living.46

HRQoL measured at baseline and at 6 months postdischarge using the Assessment of Quality of Life scale (AQOL-6D).47

A nested mixed methods process evaluation will also measure secondary outcomes using qualitative and quantitative data which evaluate participants’ response to the education using concepts of health behaviour change. This will include measuring motivation and capability to undertake falls prevention strategies in the 6 months after hospital discharge and behaviours undertaken in the 6 months after discharge that are based on the content of the education, which is tailored for each participant. Quantitative measurements will include levels of engagement in exercise (amount and type completed), levels of assistance received with ADL such as showering and IADL such as home care, changes made in the home, such as installation of equipment or rails and participants’ reports of planning to gradually increase their functional activities. These measures are collected at baseline and again at 6 months after discharge. Qualitative methodology will be used to explore the action plans that are devised by the therapists in consultation with the participants, participants’ levels of motivation and their response to the education, as well as any barriers or enablers they identify to engaging in their falls prevention action plan in the 6 months following discharge. The protocol for this mixed methods evaluation will be published separately.

Demographic data will be collected at baseline including age, medical diagnosis, length of stay in hospital, history of falls in the 12 months prior to hospital admission, number of mediations, whether psychotropic medications are taken, presence of depressed mood measured using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS),48 diagnosis of visual problems and use of walking aids.

Healthcare resource usage

Healthcare resource use by participants in the 6 months after discharge, as well as resources used during provision of the trial intervention, will be captured from four sources during the trial for use in the subsequent economic evaluation (details of the incremental cost-effectiveness analyses to be reported separately). Healthcare resource usage information to be collected during the trial will include:

Intervention provision record-keeping by research personnel relating to the frequency and duration of education sessions provided to each participant and associated record-keeping and any travel time.

Medicare Benefits Schedule and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme databases held by the Australian Government Department of Human Services. These databases capture healthcare (eg, medical appointments) and pharmaceutical use outside of the Australian hospital system (capturing both subsidy and patient out of pocket expenses).

The Western Australian Data Linkage System which identifies and links information regarding participants’ usage of healthcare resources in Western Australia (including hospital and emergency department information not available from Medicare Benefits Schedule and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme databases).

Participant interviews at monthly telephone follow-ups will capture data on other health and personal care resources (including time spent in respite or residential care) not captured elsewhere.

Procedure

The trial started recruitment in August 2015. We shall approach people for consent within ∼1 week of their anticipated discharge from hospital. Potential participants will be informed both verbally and in writing of the aims and methods of the study and be encouraged to discuss the information with their family member or other support person(s) before consenting. Those who provide written consent will be enrolled into the study. Participants will then be randomised into two groups, the intervention and control groups. Both groups will continue to receive their usual care, which includes all usual discharge planning procedures. Participants in the intervention group receive the education in addition to their usual care. Participants in the control group receive a social visit to discuss healthy ageing. At discharge, all participants will be issued with a standard falls prevention brochure and their diary and instructions on how to record falls when they return home. The diary also provides information, a monthly calendar record for each of the 6 months and instructions about how to record details of any injury and how to seek help for any injury. Participants’ families will be permitted to assist them to keep their diary and respond to telephone calls. Each month for 6 months after discharge, participants are called by outcome assessors to gather falls data and at the final call a time is made for the final discharge survey to be administered by the research assistant through a telephone call. The final phone call will measure participants’ HRQoL and functional status. Participants in the intervention group will also receive an additional phone call once per month for 6 months after discharge to consolidate the education about engagement in falls prevention strategies. This call is conducted by the educator.

Data management

Any decisions about outputs and decisions from this trial shall be ratified by the trial Management Committee (A-MH, TH, CE-B, SMM, MEM, LF, RS, MB) and each of the named investigators shall be eligible to have authorship. All data management shall be overseen for quality by our management committee. Data entry and coding of the de-identified data will be conducted by trained staff and we will use range checks for data values. Personal information about participants will be kept separate from the main data set and will not be shared. It will be maintained in a secure file server research drive at Curtin University in order to protect confidentiality before, during and after the trial. All data will be securely managed and stored at Curtin University Australia as per National Health and Medical Research Council Australia guidelines.

Safety and reporting

We shall collect, assess and report to the human research ethics committees all solicited and spontaneously reported adverse events and other unintended effects of trial interventions or trial conduct. An independent data safety monitoring board, composed of a Geriatrician and a physiotherapist, both of whom have significant clinical research expertise, will monitor the trial. Data safety and process indicators will be summarised and reviewed monthly by the principal investigator and research personnel to identify potential safety, recruitment, treatment and attrition rates and any concerns noted and also reported to the human research ethics committees.

Statistical analysis

Data will be analysed using an intention-to-treat analysis for all primary analyses using an α level set at 0.05. The primary outcome measure (rates of falls) will be analysed using negative binomial regression with adjustment for participant's length of observation in the study. This follows recommended statistical guidelines for analysing falls data.44 The proportion of people who become fallers during the observation period will be compared between groups using logistic regression. Rates of injurious falls will also be compared between groups using negative binomial regression with adjustment for participants’ length of observation in the study. Comparisons of primary and secondary fall-related outcomes between groups will be adjusted for whether the participant fell or not during hospital admission, whether they fell in the 6 months prior to hospital admission, receiving assistance with ADL prior to hospital admission, presence of depressed mood at baseline as measured by GDS and whether the participant used a walking aid or not at baseline. These covariates have each been demonstrated to be independently predictive of falls during the posthospital discharge period. Secondary outcomes of functional ability measured using the Katz and Lawtons’ scales,45 46 and HRQoL measured using AQOL-6D47 and will be compared between groups using linear regression with adjustment for the baseline values of each individual's outcome measure respectively. Protocol modifications will be reported in the final manuscript reporting the results of this trial. Statistical analyses for the process evaluation will be published separately as part of the process evaluation protocol. These analyses will include between-group comparisons of participants’ engagement in exercise, levels of assistance obtained with ADL and undertaking home modifications, as well as levels of knowledge about falls prevention and motivation to engage in falls prevention strategies. Details of the economic evaluation (including analyses of incremental cost-effectiveness) will also be published separately.

Sample size

The primary outcome (falls rates) is measured as count data and will be analysed using negative binomial/over-dispersed Poisson regression. We conducted our power calculation based on detecting a 30% relative reduction in the rate of falls (negative binomial incidence rate ratio=0.70) from a control rate of 0.80 falls per person over the 6-month follow-up (based on our previous trial with n=350 with 6 months follow-up).12 We used these data with a two-tailed α=0.05, power=0.80 and a 1:1 control to intervention allocation ratio and determined that a total sample size of N=372 was required.49 In our previous study, we had a dropout rate of <4%; therefore, we will enrol 390 patients to allow for a dropout rate of ∼5%.

Discussion

Falls remain a major source of socioeconomic burden and disability for older people2 3 and are highly problematic after discharge from hospital. Older people are a substantial subgroup within the posthospital discharge population; up to 25% of vulnerable older people incur an adverse event after discharge.14 Extensive data are now available that describe the increased incidence of falls, falls-related injuries including hip fracture, functional decline, infection, medication complications and reduced health-related quality of life.12 13 15 16 Nevertheless, there are few evidence-based resources to assist healthcare professionals to provide effective falls prevention programmes once people are discharged back to the community. Evidence-based interventions that have succeeded in reducing falls in other populations and settings have been found to be ineffective or harmful in this population, creating a need to specifically develop and test interventions for this particular high-risk population. We will be delivering a novel tailored education programme to this at-risk group of older people. The trial has presently recruited 260 participants and is expected to finish recruitment and 6 months follow-up by January 2018. Our results will inform geriatric rehabilitation practice worldwide and also be used to help develop evidence-based clinical guidelines to further prevent falls and disability in older adults.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Ronald Shorr @rshorr

Contributors: A-MH, TH, CE-B and SMM led the trial conception and design and original manuscript drafting and editing. MEM, LF, NW and RS contributed to study conception and design, trial management including data collection, original manuscript drafting, appraisal and editing. A-MH, SMM and TH led the overall trial procedures including intervention delivery protocols, data management and statistical analyses, including economic analyses, and LF, AB, CE-B and NW contributed to overall trial management and led trial management at the sites. JF-C, D-CL and MEM contributed to intervention design and delivery and MB contributed to data management and statistical analyses. All authors appraised the manuscript critically for intellectual content and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work is supported by a grant awarded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (Project grant APP1078918). The funder has no role in the design of the study and will not have any role in its execution, data management, analysis and interpretation or on the decision to submit results for publication. SMM and TH are supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (of Australia) Career Development awards.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study has been approved by the hospital (the Sir Charles Gairdner Group, number 2015-055) and university (The University of Notre Dame Australia, number 013018F) Human Research Ethics Committees.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2013). World population ageing. 2013. ST/ESA/SER.A/348.

- 2.World Health Organisation. WHO global report on falls prevention in older age. 2007 Contract No: ISBN 978 92 4 156353 6. http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Falls_prevention7March.pdf (accessed 10 May 2016).

- 3.Stevens JA, Corso PS, Finkelstein EA et al. The costs of fatal and non-fatal falls among older adults. Inj Prev 2006;12:290–5. 10.1136/ip.2005.011015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heinrich S, Rapp K, Rissmann U et al. Cost of falls in old age: a systematic review. Osteoporos Int 2010;21:891–902. 10.1007/s00198-009-1100-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Khoury F, Cassou B, Latouche A et al. Effectiveness of two year balance training programme on prevention of fall induced injuries in at risk women aged 75–85 living in community: Ossebo randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2015;351:h3830 10.1136/bmj.h3830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill TM, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA et al. Association of injurious falls with disability outcomes and nursing home admissions in community-living older persons. Am J Epidemiol 2013;178:418–25. 10.1093/aje/kws554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AIHW: Bradley C. Trends in hospitalisations due to falls by older people, Australia 1999–00 to 2010–11. Injury research and statistics no. 84. Cat. no. INJCAT 160 Canberra: AIHW, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stenhagen M, Ekström H, Nordell E et al. Accidental falls, health-related quality of life and life satisfaction: a prospective study of the general elderly population. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2014;58:95–100. 10.1016/j.archger.2013.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.AIHW: Pointer S. Trends in hospitalised injury, Australia: 1999–00 to 2012–13. Injury research and statistics series no. 95. Cat. no. INJCAT 171 Canberra: AIHW, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell AJ, Borrie MJ, Spears GF et al. Circumstances and consequences of falls experienced by a community population 70 years and over during a prospective study. Age Ageing 1990;19:136–41. 10.1093/ageing/19.2.136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vellas BJ, Wayne SJ, Garry PJ et al. A two-year longitudinal study of falls in 482 community-dwelling elderly adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1998;53:M264–74. 10.1093/gerona/53A.4.M264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill AM, Hoffmann T, McPhail S et al. Evaluation of the sustained effect of inpatient falls prevention education and predictors of falls after hospital discharge—follow-up to a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2011;66:1001–12. 10.1093/gerona/glr085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahoney JE, Palta M, Johnson J et al. Temporal association between hospitalization and rate of falls after discharge. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:2788–95. 10.1001/archinte.160.18.2788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forster AJ, Clark HD, Menard A et al. Adverse events among medical patients after discharge from hospital. CMAJ 2004;170:345–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolinsky FD, Bentler SE, Liu L et al. Recent hospitalization and the risk of hip fracture among older Americans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2009;64:249–55. 10.1093/gerona/gln027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:451–8. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51152.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen K, Mahoney J, Palta M. Risk factors for lack of recovery of ADL independence after hospital discharge. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999;47:360–5. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb03002.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL et al. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med 2007;2:314–23. 10.1002/jhm.228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greysen SR, Harrison JD, Kripalani S et al. Understanding patient-centred readmission factors: a multi-site, mixed-methods study. BMJ Qual Saf 2017;26:33–41. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill AM, Hoffmann T, Beer C et al. Falls after discharge from hospital: is there a gap between older peoples’ knowledge about falls prevention strategies and the research evidence? Gerontologist 2011;51:653–62. 10.1093/geront/gnr052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill AM, Hoffmann T, McPhail S et al. Factors associated with older patients’ engagement in exercise after hospital discharge. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011;92:1395–403. 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haines TP, Lee DC, O'Connell B et al. Why do hospitalized older adults take risks that may lead to falls? Health Expect 2015;18:233–49. 10.1111/hex.12026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee DC, McDermott F, Hoffmann T et al. ‘They will tell me if there is a problem’: limited discussion between health professionals, older adults and their caregivers on falls prevention during and after hospitalization. Health Educ Res 2013;28:1051–66. 10.1093/her/cyt091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yardley L, Beyer N, Hauer K et al. Recommendations for promoting the engagement of older people in activities to prevent falls. Qual Saf Healthcare 2007;16:230–4. 10.1136/qshc.2006.019802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bunn F, Dickinson A, Barnett-Page E et al. A systematic review of older people's perceptions of facilitators and barriers to participation in falls-prevention interventions. Ageing Soc 2008;28:449–72. 10.1017/S0144686X07006861 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee DC, Pritchard E, McDermott F et al. Falls prevention education for older adults during and after hospitalization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Educ J 2014;73:530–44. 10.1177/0017896913499266 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherrington C, Lord SR, Vogler CM et al. A post-hospital home exercise program improved mobility but increased falls in older people: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e104412 10.1371/journal.pone.0104412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill AM, McPhail SM, Waldron N et al. Fall rates in hospital rehabilitation units after individualised patient and staff education programmes: a pragmatic, stepped-wedge, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;385:2592–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61945-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill AM, Etherton-Beer C, Haines TP. Tailored education for older patients to facilitate engagement in falls prevention strategies after hospital discharge—a pilot randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e63450 10.1371/journal.pone.0063450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011;6:42 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:834–40. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cameron ID, Gillespie LD, Robertson MC et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people in care facilities and hospitals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:CD005465 10.1002/14651858.CD005465.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hodkinson HM. Evaluation of a mental test score for assessment of mental impairment in the elderly, 1972. Age Ageing 2012;41(Suppl 3):iii35–40. 10.1093/ageing/afs148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merriam S, Bierema L. . Adult learning: linking theory and practice. San Francisco: CA: Jossey-Bass (Wiley), 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol 2008;27:379–87. 10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michie S, Fixsen D, Grimshaw JM et al. Specifying and reporting complex behaviour change interventions: the need for a scientific method. Implement Sci 2009;4:40 10.1186/1748-5908-4-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DeWalt DA, Callahan LF, Hawk VH et al. Health literacy universal precautions toolkit. Chapel Hill: The Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, The University of North Carolina. 2010; Contract No.: AHRQ Publication No. 10-0046-EF. http://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/literacy-toolkit/healthliteracytoolkit.pdf (accessed 10 May 2016).

- 40.Hill AM, McPhail S, Hoffmann T et al. A randomized trial comparing digital video disc with written delivery of falls prevention education for older patients in hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:1458–63. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02346.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.World Health Organisation. 2015. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs344/en/ (accessed 10 May 2016).

- 42.Hill AM, Waldron N, Etherton-Beer C et al. A stepped-wedge cluster randomised controlled trial for evaluating rates of falls among inpatients in aged care rehabilitation units receiving tailored multimedia education in addition to usual care: a trial protocol. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004195 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hill AM, Hoffmann T, Hill K et al. Measuring falls events in acute hospitals-a comparison of three reporting methods to identify missing data in the hospital reporting system. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1347–52. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02856.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lamb SE, Jørstad-Stein EC, Hauer K et al. , Prevention of Falls Network Europe and Outcomes Consensus Group. Development of a common outcome data set for fall injury prevention trials: the Prevention of Falls Network Europe consensus. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1618–22. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Katz S. Assessing self-maintenance: activities of daily living, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. J Am Geriatr Soc 1983;31:721–7. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1983.tb03391.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969;9:179–86. 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Richardson JR, Peacock SJ, Hawthorne G et al. Construction of the descriptive system for the Assessment of Quality of Life AQoL-6D utility instrument. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012;10:38 10.1186/1477-7525-10-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res 1982;17:37–49. 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A et al. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods 2009;41:1149–60. 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013931supp.pdf (60.7KB, pdf)