Abstract

Phenylketonuria (PKU, phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency), an inborn error of metabolism, can be detected through newborn screening for hyperphenylalaninemia (HPA). Most individuals with HPA harbor mutations in the gene encoding phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH), and a small proportion (2%) exhibit tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) deficiency with additional neurotransmitter (dopamine and serotonin) deficiency. Here we report six individuals from four unrelated families with HPA who exhibited progressive neurodevelopmental delay, dystonia, and a unique profile of neurotransmitter deficiencies without mutations in PAH or BH4 metabolism disorder-related genes. In these six affected individuals, whole-exome sequencing (WES) identified biallelic mutations in DNAJC12, which encodes a heat shock co-chaperone family member that interacts with phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan hydroxylases catalyzing the BH4-activated conversion of phenylalanine into tyrosine, tyrosine into L-dopa (the precursor of dopamine), and tryptophan into 5-hydroxytryptophan (the precursor of serotonin), respectively. DNAJC12 was undetectable in fibroblasts from the individuals with null mutations. PAH enzyme activity was reduced in the presence of DNAJC12 mutations. Early treatment with BH4 and/or neurotransmitter precursors had dramatic beneficial effects and resulted in the prevention of neurodevelopmental delay in the one individual treated before symptom onset. Thus, DNAJC12 deficiency is a preventable and treatable cause of intellectual disability that should be considered in the early differential diagnosis when screening results are positive for HPA. Sequencing of DNAJC12 may resolve any uncertainty and should be considered in all children with unresolved HPA.

Keywords: DNAJC12, hyperphenylalaninemia, dystonia, neurotransmitter deficiency, phenylketonuria, tetrahydrobiopterin, BH4, newborn screening

Introduction

Phenylketonuria (PKU, phenylalanine hydroxylase [PAH] deficiency [MIM: 612349]) is the most common inborn error of amino acid metabolism.1, 2 Over the last five decades, population newborn screening (NBS) has made PKU the most successful example of a condition whose manifestations can be prophylactically managed via early intervention. Newborns with PKU who are treated early with a phenylalanine-restricted diet and/or with tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4, the PAH cofactor), which is efficacious in some individuals with PKU, can develop normally. Screening for PKU relies on measurement of elevated phenylalanine (Phe) concentrations in the newborn’s dried blood spots. Moderate hyperphenylalaninemia (moderate HPA), due to disorders of BH4 metabolism and not to PAH deficiency, accounts for approximately 1%–2% of all cases of HPA detected by NBS.1, 2, 3 Because BH4 is also a cofactor for tyrosine hydroxylase (catalyzing the conversion of tyrosine into L-dopa, the precursor of dopamine), the tryptophan hydroxylases 1 and 2 (catalyzing the conversion of tryptophan into 5-hydroxytryptophan, the precursor of serotonin), as well as PAH (catalyzing the conversion of phenylalanine into tyrosine), defects of BH4 metabolism result in a complex neurological phenotype, notably showing deficiencies of the neurotransmitters dopamine (and its metabolite homovanillic acid [HVA]) and serotonin (and its metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid [5-HIAA]), in addition to HPA. Consequently, every child with an increased Phe level on NBS must be investigated for an underlying defect of BH4 metabolism.

Here we report the identification of biallelic mutations in DNAJC12 (MIM: 606060) in six individuals from four unrelated families with HPA and dopamine and serotonin deficiencies not caused by mutations in PAH or any known defect of BH4 metabolism. DNAJC12 encodes a co-chaperone of the HSP70 family which interacts with PAH, tyrosine hydroxylase, and tryptophan hydroxylase.

Material and Methods

Clinical Methods and Ethics Statement

All clinical data were obtained with written informed consent from the parents of all investigated subjects, in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Committees of the Centers participating in this study, where biological samples were obtained. All studies were completed after local approval of the Institutional Review Board in accordance with the ethical standards of the NIH and National Human Genome Research Institute (protocol number 76-HG-0238).

Biochemical Analyses

The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations of biogenic amine metabolites, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) and homovanillic acid (HVA), pterins (neopterin, biopterin, and tetrahydrobiopterin [BH4]), and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-MTHF) were analyzed by HPLC with electrochemical or fluorescence detection or by tandem mass spectrometry (family A). Amino acid levels in the plasma and/or CSF were measured by ion-exchange chromatography.

Genetic Studies

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) was performed independently at three different centers using genomic DNA from the affected individuals A-IV-2 (family A), B-IV-1 (family B), C-II-4 (family C), and D-V-1 (family D) and the parents from families A and D, as described previously.4, 5 For family B, we performed homozygosity mapping using single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays for all of the family members, followed by WES on individual B-IV-1. All variants identified in DNAJC12 were confirmed in the affected individuals by Sanger sequencing or by PCR amplification of the junction fragment of the exon 4 deletion with the following primers: forward, 5′-ATGAGTTATATGTTCTTCCTTTTGC-3′; and reverse, 5′-CACATATTGTTGGCACCAGG-3′ (families A and D).

Expression Studies

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) and western blotting were performed to assess the DNAJC12 mRNA and protein levels in fibroblasts from individuals B-IV-1, B-IV-2 (qPCR), A-IV-2, B-IV-1, B-IV-2, and C-II-4 (western blotting) and three healthy unrelated age-matched control individuals, following previously described protocols.4 Cell lysates (20 μg) were used for detecting PAH and DNAJC12 protein by western blot. The blots were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline and Tween 20 (TBST) and then incubated with primary antibody solution: anti-PAH (Merck Millipore), anti-DNAJC12 (Abcam), and anti-β-actin overnight at 4°C. After washing with TBST, the membranes were incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (PAH and β-actin) and goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (DNAJC12), respectively, for 1 hr at room temperature. Anti-β-actin antibody, goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP, and goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP secondary antibodies were ordered from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Signals were detected with SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The relative protein levels of DNAJC12 to β-actin was quantified using ImageJ software.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical comparisons were done by Student’s t test, and the corresponding p values are provided in the figure legends.

Molecular Modeling of DNAJC12 3D Structure and Prediction of the Effects of the p.Arg72Pro Variant

To further investigate the impact of the p.Arg72Pro variant (family C) on the DNAJC12 structure, we performed molecular modeling of the DNAJC12 3D structure; the NMR structure of the J-domain of DNAJC12 is available (PDB: 2CTQ), and a model of the J-domain with the p.Arg72Pro variation was created using the SWISS-MODEL Workspace.6 Alignments of the J-domain were performed using BLAST.

Immunoprecipitation-Mass Spectrometry Analysis of the Interactions between DNAJC12, Phenylalanine Hydroxylase, Tyrosine Hydroxylase, and Tryptophan Hydroxylase 2

HEK293 cells stably expressing C-terminally HA/FLAG-tagged DNAJC12, PAH, TH, or TPH2 were obtained via lentiviral infection followed by puromycin selection for at least 1 week. The cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.8], 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP40, and protease inhibitors), and cell lysates were clarified and baits were captured with anti-FLAG magnetic beads (Sigma-Aldrich) prior to washing and elution with FLAG peptide. Eluted complexes were precipitated with 10% TCA (trichloroacetic acid), washed in acetone, and digested with trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) prior to performing analyses of two technical replicates with a ThermoFisher Q-Exactive mass spectrometer. For further details on the liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) conditions, see Huttlin et al.7 The spectra were searched using Sequest as previously described.7 CompPASS analysis was applied to distinguish high-confidence protein interactors (HCIPs) from non-specific background and false-positive identifications as previously described7 using 155 random baits as references. Proteins with NWD scores > 1, ASPM > 2, and entropy values > 0.7 that were reproducibly detected in the two datasets for the technical replicates were considered true interactors.

PAH Overexpression Studies in Control Fibroblasts and Fibroblasts from Individual C-II-4

The Phenomenex EZ:faastTM kit for LC-MS/MS sample analysis was purchased from Phenomenex. L-phenylalanine-d5 and L-tyrosine-d4 standards were obtained from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories. L-phenylalanine and L-tyrosine were obtained from Sigma Aldrich. BH4 dihydrochloride was obtained from Schircks Laboratories. Fugene HD reagent was ordered from Promega.

Fibroblasts from DNAJC12-deficient individual C-II-4 and a healthy control (both passage 7) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. The day before transfection, fibroblasts were plated in 100 mm culture dishes at 2 × 106 cells. Cell density was 50%–70% confluent on the day of transfection. Transfections were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using Fugene HD reagent. 5 μg or 10 μg of the pCMV-FLAG-PAH plasmids were transfected into fibroblasts from individual C-II-4 and a healthy control, respectively, using 25 μL or 50 μL of Fugene HD reagent in antibiotics-free media. pCMV-FLAG-PAH plasmid was a kind gift from L.R. Desviat (Madrid, Spain). Transfected cells were harvested after 48 hr for the immediate detection of PAH activity or were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

The preparation of cell lysates and the determination of PAH activity were performed as described previously.8 In brief, 20 μL (containing 50 μg of total protein) of cell homogenate was mixed with 0.1 mol/L Na-HEPES buffer, 2 μg catalase, and 1 mmol/L L-Phe. The cell mixture was incubated for 5 min, with the addition of 100 μmol/L Fe (NH4)2(SO4)2 for the last minute. The PAH activity assay reaction was started by adding 200 μmol/L BH4 and then incubating at 25°C. After 15 min, the reaction was stopped by adding 50 μL of 2% (w/v) acetic acid in ethanol. Samples were prepared for liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS/MS) according to the Phenomenex EZ:faast kit manual: 10 μL of each internal standard solution 100 μM Phe-d5 and 20 μM Tyr-d4 (in 50 mmol/L HCl) were added to 40 μL of PAH assay samples. The amount of derivatized tyrosine produced was determined by LC-ESI-MS/MS. Phenylalanine and tyrosine were determined in cell homogenates by LC-ESI-MS/MS using a Quattro Ultima triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Micromass) equipped with an electrospray ion source and a Micromass MassLynx data system. Electrospray and ion source conditions were optimized for the amino acid measurements using phenylalanine and tyrosine as internal standards. The collision gas was argon with collision energy of 14 eV. Positive ion mode was used for the analysis. A binary gradient consisting of 10 mmol/L ammonium formate in water [A] and 10 mmol/L ammonium formate in methanol [B] were used with a flow rate of 120 μL/min according to the following program: the initial conditions were 17% [A] and 83% [B]; after injection, the solvent mixtures were changed to 32% [A] and 68% [B] over 20 min, returned to the initial conditions over 7 min, and maintained at the initial conditions for 6 min. Concentrations were calculated by the signal toward internal standard ratio and an eight-point calibration curve (0–600 μmol/L for Phe and 0–120 μmol/L for Tyr). Specific PAH activity was expressed in mU/mg total protein, with mU equal to nmol tyrosine produced.

Results

Clinical Phenotype of DNAJC12-Deficient Individuals

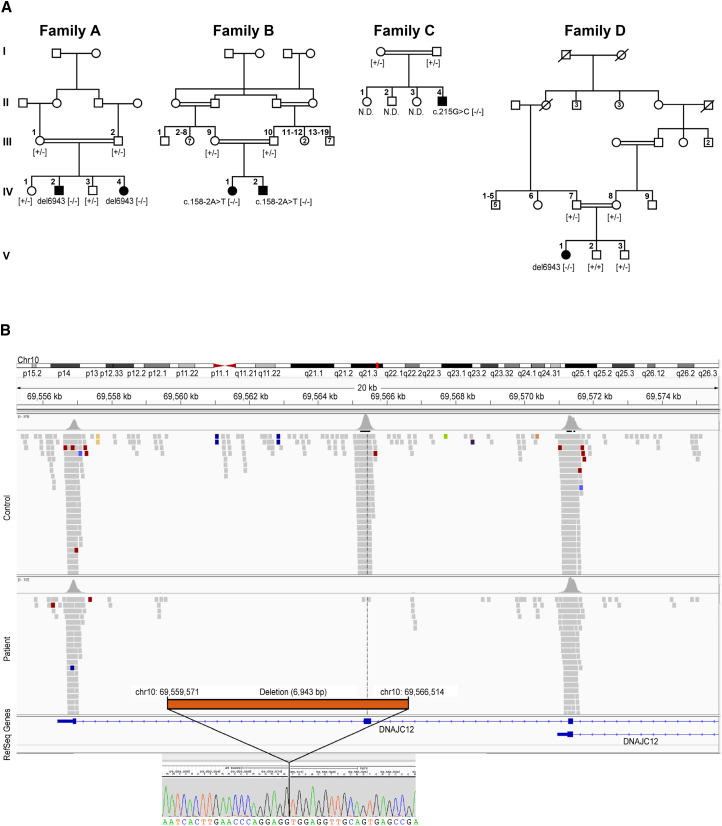

Detailed histories (pedigrees in Figure 1A) are available in the Supplemental Note. In brief, all the affected individuals exhibited HPA. Only individual A-IV-4 was identified and treated before the onset of symptoms. All the other affected individuals were investigated because of a movement disorder (Table 1) resembling that seen in BH4 metabolism disorders. Due to identification of CSF neurotransmitter deficiencies, the affected individuals were treated with various combinations of neurotransmitter precursors (a dopamine precursor, L-Dopa/carbidopa, and a serotonin precursor, 5-hydroxytryptophan) and BH4.

Figure 1.

Pedigrees of the Investigated Families and Schematic Representation of the DNAJC12 Exon 4 Deletion

(A) Pedigrees of four families with mutations in DNAJC12. The mutation status of affected (closed symbols) and healthy (open symbols) family members are noted. N.D., not determined.

(B) Schematic representation of del6943 (c.298-968_503-2603del).

Exome sequencing results (top) showing the alignment of sequencing reads to the reference genome for the controls and affected individuals (A-IV-2 and D-V-1), as visualized with the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) tool. Breakpoint junction sequences (bottom) are shown, depicting the 6.943 kb deletion (del6943, c.298-968_503-2603del) containing exon 4. The breakpoint junction sequence (chromatogram) is aligned with reference sequences.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of DNAJC12-Deficient Individuals at the Time of Diagnosis

| Developmental Delay/Intellectual Disability | Dystonia | Speech Delay | Axial Hypotonia | Limb Hypertonia | Parkinsonism | Nystagmus | Oculogyric Crisis | Attention Difficulties | Autistic Features | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-IV-2 | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| A-IV-4 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| B-IV-1 | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| B-IV-2 | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − |

| C-II-4 | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| D-V-1 | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | NA | + |

This table summarizes the clinical characteristics of all affected individuals in this study. Plus sign (+) denotes presence of clinical signs/symptoms; minus sign (−) denotes absence of clinical signs/symptoms; NA indicates information not available.

The NBS results (Table S1) were consistent with HPA in four of the affected individuals (A-IV-2, A-IV-4, B-IV-1, and C-II-4). Further investigations also confirmed HPA in B-IV-2, whose initial NBS finding was normal, and D-V-1, for whom NBS was not performed. BH4 metabolism, assessed by measuring urinary pterins and dried blood spot DHPR activity, was normal. CSF analysis of neurotransmitter metabolites and pterins (Table S1) revealed markedly decreased 5-HIAA and HVA concentrations; the HVA/HIAA ratio was elevated in five of six affected individuals (mean 8.5, range 2.9–21; normal 1.5–3.5). The baseline biopterin or BH4 level was slightly elevated in the CSF of four of the six affected individuals (A-IV-4, B-IV-1, B-IV-2, and D-V-1); however, individual D-V-1 had received BH4 supplementation before the procedure, and the treatment had been stopped for only 48 hr. In three of the four individuals with an elevated CSF baseline biopterin or BH4 level (B-IV-1, B-IV-2, and D-V-1) and in individual A-IV-2, the CSF neopterin level was slightly elevated (mean 42 nmol/L; range 35–51 nmol/L; normal, 9–30). In addition, the prolactin level was elevated in four individuals (A-IV-2, A-IV-4, B-IV-1, and C-II-4) before treatment.

CSF investigations after treatment interventions were performed for four individuals (A-IV-2, B-IV-1, B-IV-2, and C-II-4). BH4 supplementation alone did not normalize the CSF concentrations of biogenic amines in B-IV-1 and B-IV-2. Treatment with 10 mg/kg/day L-Dopa/carbidopa normalized the CSF concentration of HVA in individual A-IV-2, while treatment with 7.5 mg/kg/day did not normalize it in individual C-II-4. Only individual A-IV-2 received additional 5-hydroxytryptophan supplementation (10 mg/kg/day); this led to fluctuations between normal and elevated 5-HIAA levels (Table S1).

Molecular Diagnosis by Next Generation Sequencing

No mutations in the genes known to be associated with HPA (PAH, GCH1, PTS, QDPR, and PCBD1) or biogenic amine neurotransmitter defects (SPR, TH, DDC, DAT, and VMAT2)9 were found in any of the four families using targeted and/or whole-exome sequencing. Disease-segregating variants in DNAJC12 (GenBank: NM_021800.2; MIM: 606060), however, were independently detected by WES analysis of three families (families A, C, and D) and by homozygosity mapping combined with WES for family B. We identified a homozygous 6.943 kb deletion (del6943) which deleted entire exon 4 (c.298-968_503-2603del) (Figures 1A and 1B) in affected individuals of families A and D, while we detected a homozygous missense variant (c.215G>C [p.Arg72Pro]) in individual C-II-4 (Figure 1A). More specifically, first-pass analysis of the individuals from families A, C, and D failed to prioritize the likely clinically relevant DNA variants. Given the peculiar phenotypes of the affected individuals, their datasets were jointly reanalyzed using a data analysis pipeline optimized for the detection of copy-number variations (CNVs; ExomeDepth). Using a cut-off minor allele frequency of <0.1% in a search of 8,000 control exomes in an in-house database (Munich) and public databases, we identified 35, 58, and 14 genes with potential compound heterozygous or homozygous variants. DNAJC12 was the only gene with biallelic variants in all three individuals but not in the 8,000 in-house controls. Although the homozygous missense variant c.215G>C (p.Arg72Pro) was identified in individual C-II-4 in first-pass analysis, its clinical relevance initially remained unclear. The homozygous 6.9 kb exon 4 deletion in individuals A-IV-2 and D-V-1 was identified only during second-pass analysis that included a search for CNVs. This deletion is located in a larger region of homozygosity of 26 Mb and 68 Mb, respectively. The analysis of variants detected by WES with a SNV quality >200 (SAM tools) identified 199 variants in the smaller homozygous region in individual D-V-1. 83 of those variants in a region of 9.45 Mb are identical in both affected individuals, indicating a common founder mutation for the 6.9 kb deletion. For family B, analysis of SNP arrays of the members showed high homozygosity in both affected siblings, confirming the consanguinity, and identified 25 loci larger than 0.5 Mb distributed on 13 different chromosomes and spanning over 180 Mb (see Table S2). We then performed WES on B-IV-1’s DNA, which revealed a total of 43,090 variants. Of these variants, approximately 2,300 were in the candidate loci identified by the SNP arrays. Of them, fewer than 400 were predicted to affect the protein sequences, and only 11 had a minor allele frequency of less than 1% in the ClinSeq database10 and Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC). Ten of these variants were missense, and only three were predicted to be deleterious by both PolyPhen-2 and SIFT. These three variants were detected in CFAP45 (MIM: 605152; GenBank: NM_012337.2; c.680G>A [p.Arg227Gln]), a gene associated with nasopharynx carcinoma and pharynx cancer;11 in FSTL4 (GenBank: NM_015082.1; c.1807C>T [p.Leu603Phe]), a gene associated with coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke;12 and in SPATA31A6 (GenBank: NM_001145196.1; c.1211T>G [p.Leu404Trp]), a gene with no known function. These three variants were homozygous in some individuals in ExAC (4 for CFAP45, 1 for FSTL4, and 45 for SPATA31A6). Therefore, it was unlikely that one of these variants was the disease-causing mutation responsible for the phenotype. The most plausible candidate was the 11th variant, a splicing mutation in DNAJC12 (c.158−2A>T), which was not found in ClinSeq and was detected only once, in the heterozygous state, in ExAC. This variant, which affects the canonical acceptor site of exon 3, likely induces missplicing and therefore could lead to the creation of a null allele. For details on WES statistics, see Table S3.

Segregation analysis confirmed autosomal-recessive transmission in all families (Figure 1A). We did not identify any rare variants of likely clinical relevance in established disease-causing genes that are known to be associated with the phenotypes of affected individuals. All variants were absent from an in-house database (Munich) containing 8,000 exomes of individuals with unrelated phenotypes, as well as from public databases (ExAC). The frequency of del6943 in the public databases could not be precisely determined because of insufficient annotation, but it was not found in our CNV analysis of 5,300 datasets.

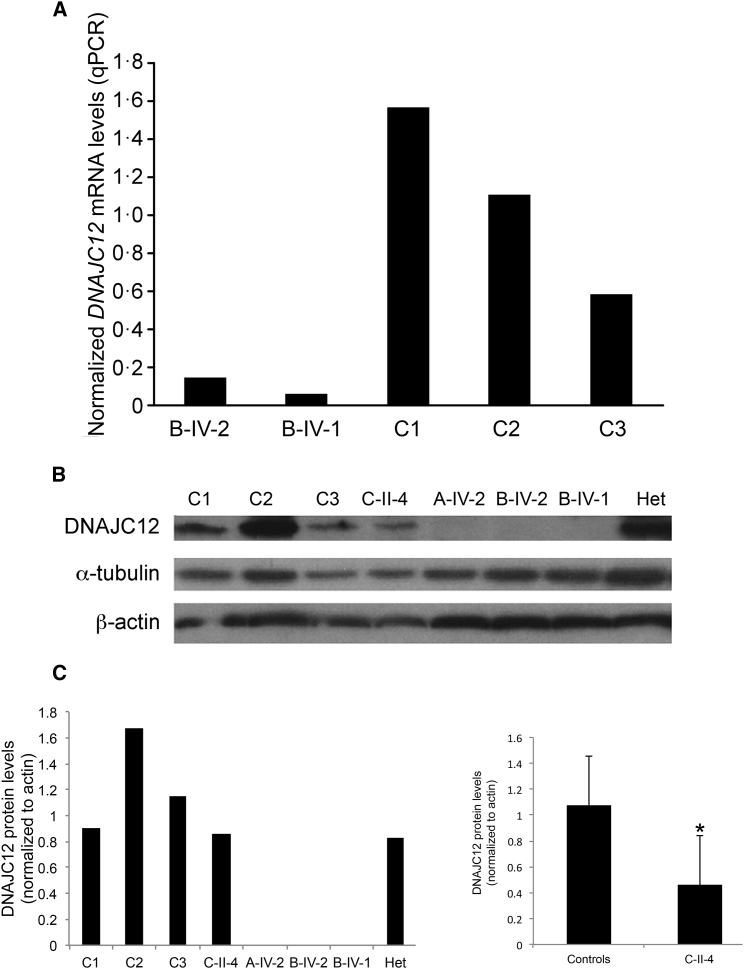

mRNA Expression and Protein Levels of DNAJC12 in Cells

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) and western blotting were performed to assess the DNAJC12 mRNA expression and protein levels in fibroblasts from individuals B-IV-1, B-IV-2 (qPCR), A-IV-2, B-IV-1, B-IV-2, and C-II-4 (western blot) and healthy unrelated age-matched control individuals. qPCR analyses showed very low DNAJC12 mRNA expression in B-IV-1 and B-IV-2 (Figure 2A). DNAJC12 protein was undetectable in the samples with the homozygous variants c.158−2A>T (B-IV-1, B-IV-2) and del6943 (A-IV-2) (Figures 2B and 2C). No significant differences in DNAJC12 protein levels were observed among control fibroblasts and those heterozygous for the canonical splice variant, c.158−2A>T (Figures 2B and 2C). In fibroblasts with the c.215G>C missense variant (C-II-4), DNAJC12 protein levels were reduced when compared to control fibroblasts (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

DNAJC12 Expression Studies

(A) DNAJC12 mRNA expression in fibroblasts, measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and standardized against GAPDH. The graph shows the normalized relative DNAJC12 mRNA levels in two affected individuals (B-IV-1 and B-IV-2) and three unaffected age-matched healthy control individuals.

(B and C) Representative western blot (B) and densitometric quantification (C, left) of the DNAJC12 protein levels in fibroblasts from three unaffected age-matched healthy control individuals (C1–C3), in fibroblasts from the heterozygous unaffected father of B-IV-1 and B-IV-2 (Het), and in fibroblasts with the homozygous missense variant (c.215G>C, C-II-4), the homozygous del6943 (A-IV-2), and the homozygous canonical splice variant (c.158−2A>T, B-IV-1 and B-IV-2). Densitometric analysis of DNAJC12 protein (C, right) was performed in fibroblasts from individual C-II-4 (n = 3) and in fibroblasts from three unaffected age-matched healthy control individuals (n = 3). DNAJC12 level was normalized to β-actin. Results are presented as means ± SEM; ∗p < 0.05.

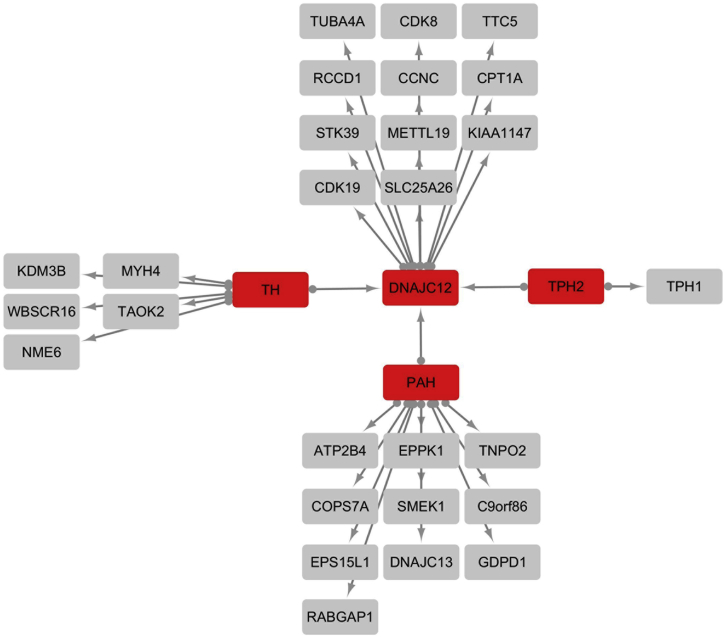

DNAJC12 Interacts with PAH, TH, and TPH2

DNAJ/HSP40 proteins, including DNAJC12, serve as co-chaperones of HSP70 members to prevent the aggregation of misfolded or otherwise aggregation-prone proteins through a process involving preferential interactions with misfolded forms of these proteins.13, 14, 15 DNAJC12 is a type III DNAJ/HSP40 protein, also referred to as a subfamily C protein; this subfamily includes at least 23 members with relative specificity for their designated substrate proteins.16 However, little is known about the target specificity of DNAJC12. Affinity capture-mass spectrometry data from the human interactome have recently shown that DNAJC12 interacts with several proteins, including tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), peripheral tryptophan hydroxylase 1 (TPH1), and neuronal TPH2 (BioGRID).7 Overexpression of TPH2 and TH in HEK293 cells confirmed the interactions between these two hydroxylases and DNAJC12 (Figure 3). We could also demonstrate interaction between DNAJC12 and PAH by overexpressing PAH in HEK293 cells (Figure 3). Interestingly, an interaction between PAH and JDP, the apparent protein ortholog of DNAJC12 in Drosophila melanogaster (67.5% sequence similarity; Figure S2B), was detected in the two-hybrid-based protein-interaction map of Drosophila melanogaster17 (BioGRID).

Figure 3.

Overview of the DNAJC12, PAH, TH, and TPH2 Protein Interaction Network, as Determined by Immunoprecipitation-Mass Spectrometry Analysis

C-terminally tagged DNAJC12, PAH, TH, and TPH2 were immunopurified from HEK293 cells, and protein complexes were analyzed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. CompPASS analysis was performed in technical duplicates. Proteins with NWD scores > 1, ASPM > 2, and entropy values > 0.7 that were reproducibly detected in the two CompPASS analyses were considered high-confidence interactors. Baits are represented in red. High-confidence interacting proteins (HCIPs) are represented in gray.

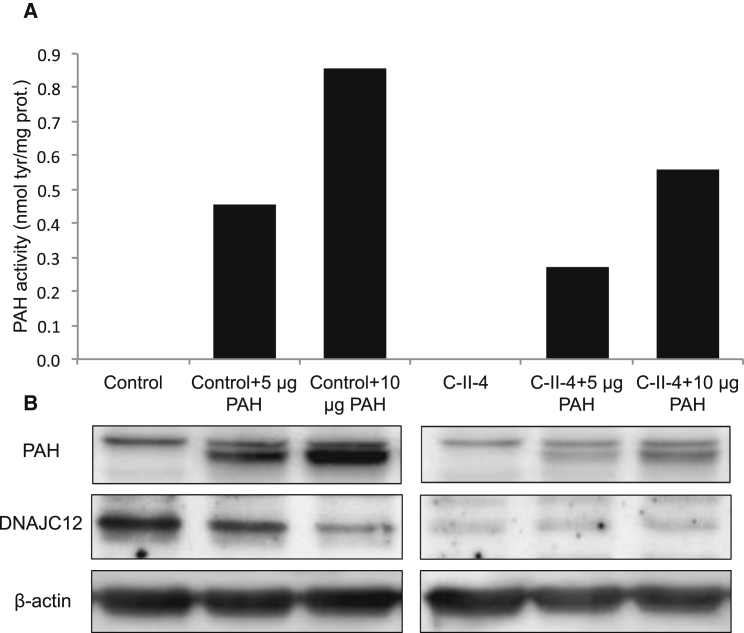

PAH Activity Is Reduced in the Presence of DNAJC12 Mutations

Finally, to further demonstrate reduced PAH enzyme activity in the presence of DNAJC12 mutations, we opted to overexpress PAH in fibroblasts from individual C-II-4. Indeed, PAH expression in fibroblasts is minimal.18 Similarly for HEK293 cells where we checked an extensive library of HEK293 proteomics data spanning several thousand LC-MS runs,7 we confirmed that all three aromatic amino acid hydroxylases (AAAH, namely PAH, TH, and TPHs) were absent. Regardless, we could demonstrate that fibroblasts with the homozygous c.215G>C missense variant (C-II-4) exhibited a lower PAH enzymatic activity than control fibroblasts upon PAH overexpression (Figure 4A). Similarly, both PAH endogenous protein levels and levels of overexpressed PAH were reduced in C-II-4 fibroblasts compared to control fibroblasts (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Phenylalanine Hydroxylase Enzyme Activity Is Reduced in the Presence of DNAJC12 Mutations

(A) PAH activity was measured using liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry in fibroblasts with the homozygous missense variant (c.215G>C, individual C-II-4) and in fibroblasts from an unaffected age-matched healthy control after 5 μg or 10 μg PAH plasmids transfection.

(B) Western blot assay of PAH, DNAJC12, and β-actin proteins in individual C-II-4 and control fibroblasts after 5 μg or 10 μg PAH plasmids transfection.

Discussion

We report biallelic mutations of DNAJC12 in six affected individuals from four families with HPA and dopamine and serotonin deficiencies not caused by mutations in PAH or any known BH4 metabolism genes. As expected, DNAJC12 mRNA expression was markedly reduced from fibroblasts of individuals with the splicing variant (family B). Data on protein levels established that both this canonical splice variant and the exon 4 deletion (del6943, families A and D) were null variants; the missense variant (c.215G>C [p.Arg72Pro], family C) affected DNAJC12 stability. Indeed, this point mutation is located in the J-domain that spans positions 14 to 79 in DNAJC12 (UniProt) and promotes functional interactions with chaperones of the HSP70 family by stimulating their ATPase activity.16 The J-domain is remarkably conserved in the DNAJ/HSP40 family, and it includes an invariant His, Pro, Asp (HPD) motif located in the loop between helices II and III (Figure S1) that is crucial for binding to HSP70 proteins and for ATPase stimulation.16 Hence, since the highly conserved Arg72 is essential for maintaining the 3D structure of the J-domain through hydrogen bonding interactions with Ser25, a mutation affecting the highly conserved Arg72 (Figures S1 and S2), the variant p.Arg72Pro, is expected to be deleterious and pathogenic, as estimated by a CADD score19 of 33 and FATHMM-MKL score20 of −8.53 (cutoffs for deleteriousness at 15 and −1.5, respectively). Indeed, the p.Arg72Pro variant would destroy the stabilizing network within the J-domain and, consequently, DNAJC12 stability and functional interaction with proteins of the HSP70 family. In fact, FoldX21 structural modeling (Figure S1) predicts the difference in protein stability of the p.Arg72Pro mutant relative to the wild-type J-domain of DNAJC12 (ΔΔG) to be 13.6 kcal/mol, indicating significant instability.

While it is crucial to exclude defects in BH4 synthesis or recycling whenever HPA is identified,2 urinary pterins and DHPR activity were unfortunately normal in all of the individuals with biallelic DNAJC12 mutations. An elevated plasma prolactin concentration might lead to a suspicion of central dopamine deficiency, but this parameter is nonspecific and fluctuates with circadian changes, physical activity, or exposure to emotional stress (e.g., blood draws).22 The identification of CSF dopamine and serotonin deficiencies along with a high HVA/5-HIAA ratio could provide a diagnostic indicator of an underlying DNAJC12 deficiency; however, a spinal tap is considered rather invasive, especially for infants, and is not always available. Because the timely detection and initiation of specific treatment are important in this disorder, DNAJC12 genetic analysis should be performed for every child with non-PKU HPA and negative screening results for BH4 metabolism defects. This is especially true if Phe blood concentrations decrease to less than 120 μM within 6 hr after a 20 mg/kg BH4 loading oral dose as observed for individual A-IV-2 (Table S1).

Whereas DNAJC12 may interact with more proteins than the four AAAHs, these interactions need to be further validated. In addition, in terms of clinical and biochemical phenotype, affected individuals in our study exhibited consistent findings without any additional biochemical or clinical hallmarks. The specific neurological manifestations of our DNAJC12-deficient individuals might be attributed to high levels of DNAJC12 in brain (UniProt), accounting for the high CSF Phe levels (A-IV-2, A-IV-4, B-IV-1, C-II-4, and D-V-1) and biogenic amines CNS deficiencies as the major phenotypic hallmarks. Similar to DNAJB6, mutations in a ubiquitously expressed gene could exert effects in a tissue-specific manner.15

All affected individuals received BH4 with or without L-Dopa/carbidopa/5-hydroxytryptophan and all showed a favorable response when treatment was initiated early. Similarly variable therapeutic responses have been observed among individuals with BH4 metabolism disorders and depend largely on the timing of treatment initiation.23 Furthermore, the beneficial effect of BH4 supplementation on the DNAJC12-deficient individuals presented here may be explained by a role of BH4 not only in supporting the AAAH reactions but also as a pharmacological chaperone that increases the stability of these enzymes similar to what occurs in BH4-responsive PKU.24

Variations in therapeutic effects could also be ascribed to the variable effects of the different DNAJC12 mutations. Early treatment can alter or even prevent severe neurological disease, as illustrated by A-IV-4 and D-V-1, who harbored the same variant (del6943) and seemed to represent the two ends of the clinical spectrum of DNAJC12 deficiency. After early screening and treatment, A-IV-4 exhibited normal neurodevelopment at 22 months of life, while individual D-V-1, who received treatment late, developed progressive impairments in motor and intellectual development and severe autism spectrum disorder, the latter being probably ascribable to the severity of CNS impairment and therefore a nonspecific finding. Though unlikely due to WES results, a coincidental non-recessive mutation in another gene than DNAJC12 at the origin of the autistic phenotype cannot be excluded. This observation denotes the importance of early diagnosis and treatment in DNAJC12 deficiency, similar to other BH4 metabolism disorders. Of note, long-term follow-up of early identified and treated DNAJC12-deficient individuals (such as A-IV-4) will be mandatory to confirm whether early therapy allows complete prevention of any neurocognitive deterioration. In follow-up investigations, the different treatments (BH4 and/or one or two of the neurotransmitter precursors) yielded variable biochemical outcomes among the affected individuals, and treatment with the combination of BH4 and the neurotransmitter precursors most effectively corrected the biochemical abnormalities. Thus, it seems reasonable to treat individuals with DNAJC12 deficiency with the combination of neurotransmitter precursors and BH4, as for individuals with BH4 disorders.25

In conclusion, DNAJC12 deficiency is a prophylactically treatable genetic cause of HPA that is not due to PAH deficiency or impaired BH4 metabolism. Untreated DNAJC12 deficiency clinically mimics BH4 metabolism defects, leading to a progressive movement disorder with prominent dystonia and ID. It can be identified early in life via NBS for HPA and should be considered in the early differential diagnosis when screening results are positive for HPA. Diagnoses of DNAJC12 deficiency must be investigated by molecular analysis (sequencing of DNAJC12) in all children with HPA, especially those in consanguineous families, after having ruled out PKU and BH4 metabolism disorders by PAH sequencing and measurement of urinary or dried blood pterins concentrations and dried blood DHPR activity. NBS allows for early detection and treatment, which can apparently ensure a normal cognitive outcome (family A); in contrast, affected individuals who receive late treatment and those who are not treated exhibit moderate to severe neurodevelopmental delay that cannot be resolved with later treatment. Treatment must be initiated as early as possible and includes BH4 and dopamine and serotonin precursors. Early DNAJC12 molecular screening and treatment are crucial for preventing irreversible damage, similar to thousands of individuals with PKU or BH4 metabolism disorders.25

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the participants in this study and their families for their cooperation and support. We would also like to acknowledge the professional manuscript services of American Journal Experts (AJE). This study was supported in part by the NIH National Human Genome Research Intramural Research Program; the NIH (U41 HG006673); the Dietmar Hopp Foundation; St. Leon-Rot, the German Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) through the German Network for Mitochondrial Disorders (mitoNET, 01GM1113C) and the Juniorverbund in der Systemmedizin “mitOmics” (FKZ 01ZX1405C); the E-Rare project GENOMIT (01GM1207); the EU Horizon 2020 Collaborative Research Project SOUND (633974); and the Illig-Stiftung for HPA individuals and the FP7-HEALTH-2012-INNOVATION-1 EU Grant No. 305444 (RD-CONNECT).

Published: January 26, 2017

Footnotes

Supplemental Data include clinical case reports, two figures, and three tables and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.01.002.

Contributor Information

Yair Anikster, Email: yair.anikster@sheba.health.gov.il.

Manuel Schiff, Email: manuel.schiff@aphp.fr.

Web Resources

1000 Genomes, http://www.internationalgenome.org/

BioGRID, http://thebiogrid.org/

dbSNP v.142, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/

ExAC Browser (accessed March 2016), http://exac.broadinstitute.org/

fathmm v2.3, http://fathmm.biocompute.org.uk/

FoldX, http://foldxsuite.crg.eu/

GenBank, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/

OMIM, http://www.omim.org/

PolyPhen-2, http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/

RCSB Protein Data Bank, http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/home/home.do

SWISS-MODEL, http://swissmodel.expasy.org/

UniProt, http://www.uniprot.org/

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Blau N. Genetics of phenylketonuria: then and now. Hum. Mutat. 2016;37:508–515. doi: 10.1002/humu.22980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blau N., van Spronsen F.J., Levy H.L. Phenylketonuria. Lancet. 2010;376:1417–1427. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60961-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blau N., Hennermann J.B., Langenbeck U., Lichter-Konecki U. Diagnosis, classification, and genetics of phenylketonuria and tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) deficiencies. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2011;104(Suppl):S2–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stephen J., Vilboux T., Haberman Y., Pri-Chen H., Pode-Shakked B., Mazaheri S., Marek-Yagel D., Barel O., Di Segni A., Eyal E. Congenital protein losing enteropathy: an inborn error of lipid metabolism due to DGAT1 mutations. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2016;24:1268–1273. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2016.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haack T.B., Hogarth P., Kruer M.C., Gregory A., Wieland T., Schwarzmayr T., Graf E., Sanford L., Meyer E., Kara E. Exome sequencing reveals de novo WDR45 mutations causing a phenotypically distinct, X-linked dominant form of NBIA. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;91:1144–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guex N., Peitsch M.C., Schwede T. Automated comparative protein structure modeling with SWISS-MODEL and Swiss-PdbViewer: a historical perspective. Electrophoresis. 2009;30(Suppl 1):S162–S173. doi: 10.1002/elps.200900140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huttlin E.L., Ting L., Bruckner R.J., Gebreab F., Gygi M.P., Szpyt J., Tam S., Zarraga G., Colby G., Baltier K. The BioPlex Network: a systematic exploration of the human interactome. Cell. 2015;162:425–440. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heintz C., Troxler H., Martinez A., Thöny B., Blau N. Quantification of phenylalanine hydroxylase activity by isotope-dilution liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012;105:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng J., Papandreou A., Heales S.J., Kurian M.A. Monoamine neurotransmitter disorders--clinical advances and future perspectives. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015;11:567–584. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biesecker L.G., Mullikin J.C., Facio F.M., Turner C., Cherukuri P.F., Blakesley R.W., Bouffard G.G., Chines P.S., Cruz P., Hansen N.F., NISC Comparative Sequencing Program The ClinSeq Project: piloting large-scale genome sequencing for research in genomic medicine. Genome Res. 2009;19:1665–1674. doi: 10.1101/gr.092841.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bueno R., Stawiski E.W., Goldstein L.D., Durinck S., De Rienzo A., Modrusan Z., Gnad F., Nguyen T.T., Jaiswal B.S., Chirieac L.R. Comprehensive genomic analysis of malignant pleural mesothelioma identifies recurrent mutations, gene fusions and splicing alterations. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:407–416. doi: 10.1038/ng.3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luke M.M., O’Meara E.S., Rowland C.M., Shiffman D., Bare L.A., Arellano A.R., Longstreth W.T., Jr., Lumley T., Rice K., Tracy R.P. Gene variants associated with ischemic stroke: the cardiovascular health study. Stroke. 2009;40:363–368. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.521328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dekker S.L., Kampinga H.H., Bergink S. DNAJs: more than substrate delivery to HSPA. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2015;2:35. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2015.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Månsson C., Arosio P., Hussein R., Kampinga H.H., Hashem R.M., Boelens W.C., Dobson C.M., Knowles T.P., Linse S., Emanuelsson C. Interaction of the molecular chaperone DNAJB6 with growing amyloid-beta 42 (Aβ42) aggregates leads to sub-stoichiometric inhibition of amyloid formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:31066–31076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.595124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarparanta J., Jonson P.H., Golzio C., Sandell S., Luque H., Screen M., McDonald K., Stajich J.M., Mahjneh I., Vihola A. Mutations affecting the cytoplasmic functions of the co-chaperone DNAJB6 cause limb-girdle muscular dystrophy. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:450–455. doi: 10.1038/ng.1103. S1–S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kampinga H.H., Craig E.A. The HSP70 chaperone machinery: J proteins as drivers of functional specificity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11:579–592. doi: 10.1038/nrm2941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giot L., Bader J.S., Brouwer C., Chaudhuri A., Kuang B., Li Y., Hao Y.L., Ooi C.E., Godwin B., Vitols E. A protein interaction map of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2003;302:1727–1736. doi: 10.1126/science.1090289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bjørgo E., Knappskog P.M., Martinez A., Stevens R.C., Flatmark T. Partial characterization and three-dimensional-structural localization of eight mutations in exon 7 of the human phenylalanine hydroxylase gene associated with phenylketonuria. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998;257:1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2570001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kircher M., Witten D.M., Jain P., O’Roak B.J., Cooper G.M., Shendure J. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:310–315. doi: 10.1038/ng.2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shihab H.A., Rogers M.F., Gough J., Mort M., Cooper D.N., Day I.N., Gaunt T.R., Campbell C. An integrative approach to predicting the functional effects of non-coding and coding sequence variation. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1536–1543. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schymkowitz J., Borg J., Stricher F., Nys R., Rousseau F., Serrano L. The FoldX web server: an online force field. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W382–W388. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Kerkhof L.W., Van Dycke K.C., Jansen E.H., Beekhof P.K., van Oostrom C.T., Ruskovska T., Velickova N., Kamcev N., Pennings J.L., van Steeg H., Rodenburg W. Diurnal variation of hormonal and lipid biomarkers in a molecular epidemiology-like setting. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0135652. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leuzzi V., Carducci C.A., Carducci C.L., Pozzessere S., Burlina A., Cerone R., Concolino D., Donati M.A., Fiori L., Meli C. Phenotypic variability, neurological outcome and genetics background of 6-pyruvoyl-tetrahydropterin synthase deficiency. Clin. Genet. 2010;77:249–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blau N., Erlandsen H. The metabolic and molecular bases of tetrahydrobiopterin-responsive phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2004;82:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Opladen T., Hoffmann G.F., Blau N. An international survey of patients with tetrahydrobiopterin deficiencies presenting with hyperphenylalaninaemia. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2012;35:963–973. doi: 10.1007/s10545-012-9506-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.