Abstract

Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc) bacteria emerged as opportunistic pathogens in cystic fibrosis and immunocompromised patients. Their eradication is very difficult due to the high level of intrinsic resistance to clinically relevant antibiotics. Bcc bacteria have large and complex genomes, composed of two to four replicons, with variable numbers of insertion sequences. The complexity of Bcc genomes confers a high genomic plasticity to these bacteria, allowing their adaptation and survival to diverse habitats, including the human host. In this work, we review results from recent studies using omics approaches to elucidate in vivo adaptive strategies and virulence gene regulation expression of Bcc bacteria when infecting the human host or subject to conditions mimicking the stressful environment of the cystic fibrosis lung.

Keywords: Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc), cystic fibrosis (CF), post-genomic approaches, adaptive strategies

1. Introduction

The Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc) is a group of 20 closely-related bacterial species, with up to 78% of their genes in common [1]. These bacteria have large genomes ranging from 7 to more than 9 Mbs, typically arranged in three chromosomes and a large plasmid [1,2]. Bcc emerged in the early 1980s as opportunistic human pathogens capable of causing particularly severe and life-threatening infections to cystic fibrosis (CF) patients [3,4]. Although all the Bcc species have the potential to infect CF patients, Burkholderia cenocepacia and Burkholderia multivorans account for the large majority of isolates from these patients [5,6]. Bcc infections are especially feared by CF patients due to the intrinsic resistance of these bacteria to current antimicrobial agents and the cepacia syndrome, a fast and often lethal necrotizing pneumonia accompanied with septicemia developed by up to 20% of the infected patients [7,8]. Epidemiology studies performed in the 1980s and 1990s showed that outbreaks in CF centers were mainly caused by particularly virulent and transmissible B. cenocepacia strains like the ET12, the PHDC, and the Midwest lineages [4]. Segregation measures adopted worldwide led to a reduction of B. cenocepacia prevalence. Most probably as a result of these measures, the emergence of non-clonal strains of Bcc species like B. multivorans, Burkholderia contaminans, and Burkholderia dolosa is now apparent.

Several virulence factors have been described for Bcc bacteria (reviewed in [4,5,9]). However, the exact role they play when the bacterium is infecting the CF host remains to be fully elucidated. In recent years, several studies have been performed aiming at the understanding of the strategies used by Bcc to survive and thrive in the CF host and how the bacterium adapts its gene expression program to survive the hostile environment that is the CF host. These studies make use of whole genome sequencing approaches and global transcriptomics analyses, only possible now due to the recent developments achieved in post-genomic techniques. Here we review selected studies based on the comparative genomics and/or quantitative transcriptomics of Bcc isolates when infecting the CF host.

2. Genomics and Transcriptomics Analysis in the Study of Bcc Pathogenesis

When infecting the airways of CF patients, Bcc bacteria experience stressful conditions, in particular those resulting from a challenging host immune defense, aggressive antimicrobial therapy, nutrient availability and oxygen limitation, among other stresses [10,11]. Despite the description of several virulence factors of the Bcc [4,5,12], the process of adaptation to the airways of CF patients is still poorly understood. Selected recent studies involving whole genome sequencing to characterize in vivo evolution of genomes, as well as transcriptomics analyses of Bcc when infecting the CF host or subject to conditions mimicking the CF lung conditions, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of major findings obtained in selected genomics and transcriptomics studies related to Burkholderia cepacia complex pathogenesis in the cystic fibrosis (CF) lung.

| Experiment | Major Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Genomics | ||

| Retrospective study of a B. dolosa outbreak among CF patients by sequencing the genomes of a single colony of 112 isolates collected from 14 individuals over 16 years. | 17 bacterial genes acquired non-synonymous mutations in multiple individuals, indicating parallel adaptive evolution. Mutated genes involved in antibiotic resistance, bacterial membrane composition, and oxygen-dependent gene expression regulation. |

Lieberman et al., 2011 [13] |

| Analysis of intraspecies diversity in the sputum of five CF patients infected with B. dolosa. | Several bacterial lineages coexisted within the same patient. Genes subject to strongest selection are involved in outer membrane component synthesis, iron scavenging and antibiotic resistance. |

Lieberman et al., 2014 [14] |

| Genomic and functional evolution analysis of 22 B. multivorans isolates sequentially collected over 20 years. | Population diversified into four primary, coexisting clades, with distinct evolutionary dynamics. Strong selection of genes involved in B. multivorans populations during long-term colonization of CF patient lung targets adherence, metabolism, and cell envelope changes related to adaptation to the biofilm lifestyle. |

Silva et al., 2016 [15] |

| Genome-wide comparative analysis of two B. contaminans isolates, from sputum and from blood culture. | The sputum isolate differs from the bloodstream isolate by over 1400 mutations as a result of a mismatch repair-deficient hypermutable state. | Nunvar et al., 2016 [16] |

| Transcriptomics | ||

| Comparative transcriptomics of two clonal isolates of B. cenocepacia in different stages of chronic infection, recovered from a long-term colonized CF patient deceased with cepacia syndrome. | The later isolate presented upregulated genes involved in translation, iron acquisition, efflux of drugs, and adhesion to respiratory epithelial surface. Alterations related to adaptation to the nutritional environment of the CF lung and to oxygen-limitation. |

Mira et al., 2011 [17] |

| Comparative transcriptomics of two pan-resistant ET12 outbreak isolates recovered two decades after J2315. | The outbreak strains exhibited downregulation of genes involved in flagella production and chemotaxis; upregulation of genes involved in transport and efflux, restriction modification, and transposition. | Sass et al., 2011 [18] |

| Comparative transcriptomics of B. cenocepacia isolates from the bloodstream of CF patients with cepacia syndrome with isolates recovered from sputum one to two months before the cepacia syndrome. | Blood isolates presented a higher level of expression of virulence genes involved in type III secretion, exopolysaccharide cepacian biosynthesis, and quorum sensing, and reduced expression of flagellar genes. | Kalferstova et al., 2015 [19] |

| Comparative transcriptomics of two B. contaminans isolates from sputum and blood culture of a CF patient. | Differential expression of quorum sensing-regulated virulence factors, motility, and chemotaxis; the low-oxygen-activated (lxa) locus encoding stress-related proteins; and two clusters responsible for the biosynthesis of the antifungal and hemolytic compounds pyrrolnitrin and occidiofungin. | Nunvar et al., 2016 [16] |

The airways of CF patients are prone to long-term bacterial infections by bacterial strains that persist for many years, allowing significant time for genetic adaptation [6]. During this process, bacterial pathogens can accumulate mutations that will allow them to adapt to the human host [20], evade the immune response [21], and become more resistant to antibiotic therapy [22]. Post-genomic methodologies such as comparative genomics analyses are powerful tools to identify genes that underwent selective pressure during infection in CF patients.

Using a post-genomic approach, Lieberman and colleagues (2011) identified genes under adaptive evolution by tracking frequent patterns of mutations in the same pathogenic B. dolosa strain during the infection of multiple CF patients [13]. Using this approach, 17 genes conserved in the Burkholderia genus were found as subject to positive selection. The genes accounting for the highest number of mutations were gyrA, the glycosyltransferase wbaD, and the BDAG_01161 gene, and a homolog of fixL. These genes are involved in antibiotic resistance, O-antigen presentation and oxygen-dependent gene expression regulation, respectively [13]. Eleven of the mutated genes belong to functional categories already known to play a role in Bcc virulence, such as membrane synthesis, secretion, and antibiotic resistance [13]. However, the six remaining mutated genes were novel virulence determinants for Bcc and three of them (a glucoamylase, a sigma factor, and a methyltransferase) have no well-annotated homologs and have unclear roles in bacterial pathogenicity. The other three genes, homologs of fnr, fixL, and fixJ, are involved in oxygen-dependent gene expression regulation in bacteria and can be linked to the adaptation of the bacterium to the lowered oxygen tension in the CF mucus [23,24].

To understand if the beneficial mutations became fixed in the population or have an intermediate frequency and coexist with other lineages, Lieberman and colleagues studied the genotypic diversity of B. dolosa within CF patients by resequencing individual colonies and whole populations from single sputum samples [14]. These authors observed that, under strong selection, multiple adaptive mutations appeared, but none stay fixed in the population, originating diverse bacterial lineages that can coexist for many years.

B. multivorans is currently the predominant Bcc species infecting CF patients in France and Canada [6,25]. To identify the pathoadaptive mechanisms associated with long-term persistence of B. multivorans in the CF patient’s lungs, Silva and colleagues [15] sequenced the genomes of 22 B. multivorans isolates recovered over the 20 years of chronic colonization of a patient from whom isolates presented a mucoid-to-nonmucoid transition. Similarly to the evolutionary patterns observed for B. dolosa, results from this study also show that the adaptation of B. multivorans to the CF lung occurred through the slow accumulation of selected mutations. The genes identified as being under strong positive selection contained mutations that produced long-lived lineages (for instance, in the rpfR gene with the resulting elevated c-di-GMP intracellular levels), together with genes that accumulated mutations over time leading to altered key functions (e.g., fixL, plsX, hfq, ompR-like gene, fis-like gene). In addition, 10 loci bearing three or more independent mutations mainly involved in gene expression regulation and lipid metabolism were also identified. However, a frameshift in mutL that led to an increased mutation rate was observed for the last serial isolate, which represents an exception to the slow adaptation dynamics found for all the other isolates [15]. The emergence of hypermutators during evolution in CF lungs is a widespread phenomenon already reported for other bacterial pathogens, as well as for Bcc isolates from CF [26,27]. The accelerated evolutionary rates of mutator lineages have been previously shown to increase their antibiotic resistance, rendering their eradication more difficult [27].

A recent comparative transcriptomics and genomics study of two B. contaminans isolates recovered from blood and sputum revealed that the sputum isolate harbored mutations in mutS and mutL, indicating that adaptation to the patient lung led to a hypermutator phenotype [16].

To understand the adaptive responses that might occur during long-term infection with B. cenocepacia in the stressful environment of the CF lung under antimicrobial therapy, a comparative transcriptomics analysis was carried out for the initial B. cenocepacia isolate IST439 and its clonal variant IST4113, obtained three years later [17]. Using a 1.5-fold threshold as the cut-off value, 1024 genes were found as differentially expressed in these two variants, with 534 genes upregulated and 490 downregulated [17]. In this study, an important role for acyl-homoserine lactones (AHL)-mediated quorum sensing in the establishment of the chronic infection was noticed, with the cciR gene upregulated in the later isolate and 94 genes previously known as CciR-dependent exhibiting altered expression. For the later isolate, the upregulation of genes involved in translation, iron acquisition, drug efflux pumps, and cell envelope and outer membrane biogenesis were also observed. Upregulation of genes encoding amino acid transporters or catabolism, and downregulation of several cytochromes required for electron transfer under aerobic conditions, together with upregulation of genes required for microaerophilic conditions in the later isolate suggest an adaptation to the nutritional environment of the CF lung and to an oxygen-limited environment, respectively [17].

Bcc infections in CF patients usually cause chronic respiratory infections. Additionally, these infections pose a high risk for the development of the cepacia syndrome (CS) which is characterized by pulmonary exacerbation, high levels of inflammatory markers, and positive blood culture for Bcc [19]. Despite its clinical relevance, the mechanism underlying the onset and development of CS remains limited. In order to understand the bacterial factors associated with CS, the transcriptomic profile of isolates recovered from the blood and sputum of a patient with the CS was carried out [19]. The bloodstream bacterial isolates were found to express genes involved in the type III secretion system and the exopolysaccharide cepacian at higher levels and to suppress the activity of the flagellar system. It was also observed that changes in bacterial motility were almost exclusively observed in cases of B. cenocepacia infection that resulted in CS. The loss of motility was observed in isolates recovered from the sputum up to 24 months before the development of CS [19].

Aiming at the study of the natural evolution of the ET12 epidemic lineage circulating in the CF community since the recovery of the J2315 strain in 1989 and mapping the multiple antimicrobial resistance pathways of J2315, the transcriptomics analysis of two pan-resistant ET12 outbreak isolates recovered two decades after J2315 were compared with the transcriptome of J2315 [18]. Genes involved in flagella production and in chemotaxis were downregulated in the outbreak isolates. Genes involved in transport and efflux, restriction modification, and transposition were upregulated in the outbreak isolates. In particular, the gene BCAS0081 encoding an ABC membrane transport protein probably involved in antimicrobial resistance was highly expressed [18].

Several transcriptomics analyses of Bcc strains provided new knowledge on non-coding regulatory RNAs (sRNAs) [28], differential gene expression in CF sputum [29], and in artificial sputum versus soil-based medium [30,31], and in nine different growth conditions mimicking conditions that can occur in the environment or in the CF lung [11]. These studies have also contributed to the identification of several genes involved in quorum sensing regulation [32,33,34], antibiotic resistance [18,35], and biofilm formation and resistance [36,37,38,39].

3. Known Regulators of Bcc Virulence Factors

In spite of the huge amount of data generated from comparative genomics and transcriptomics studies, the exact function of specific genes is often limited. In addition, about 15% of the genes of B. cenocepacia J2315 (one of the best studied Bcc strains) still have no predicted function or only a general function predicted. Bcc bacteria occupy a diverse array of niches, including the rhizosphere, plants, animals and humans [5], requiring finely-tuned regulatory mechanisms that enable them to adapt to diverse environments and different stresses. In this section, we present a summarized description of known regulators of virulence of Bcc bacteria.

3.1. Sigma Factors and Related Proteins

During bacterial evolution, selective pressure caused by different environmental conditions has been shown to favor the emergence of several paralogous lineages of σ70 [40]. In the ET12 lineage strain B. cenocepacia J2315, 20 σ70 paralog genes were identified, with 14 of them belonging to the extracytoplasmic function (ECF) family [40]. These identified σ70 paralogs were shown to have a clade-specific distribution, with ecfA2 and sigI restricted to ET12 lineage strains and Bcc species, respectively [40]. Some σ70 paralogous genes are only present in the Burkholderia genus (ecfJ, ecfF and sigJ), or in proteobacteria (ecfA1, ecfC, ecfD, ecfE, ecfG, ecfL, ecfM, and rpoS). Common eubacterial σ70 paralogous genes (ecfI, ecfK, ecfH, ecfB, and rpoD-, rpoH-, fliA-like genes) were also identified.

It was shown by transcriptomic assays that four sigma factors (BCAL0787 or σ32, BCAL1369 or FecI, BCAL1688 or OrbS, and BCAL3478) were upregulated in sessile cells of B. cenocepacia J2315 in response to oxidative stress [36].

A mechanism used by bacteria to adapt to stress involves the activity of the alternative sigma factor RpoE, an important regulator of the extracytoplasmic stress response [41]. A B. cenocepacia K56-2 rpoE mutant was found to present cell envelope alterations, exhibiting growth defects under elevated temperature and osmolarity [42]. RpoE was also shown to be required for the B. cenocepacia ability to delay phagolysosomal fusion in macrophages, allowing the bacteria to survive intracellularly [42]. Results from the mapping of the σ54 regulon and the characterization of a σ54 mutant derived from B. cenocepacia H111 suggest that this alternative sigma factor plays an important role in the control of nitrogen metabolism, in the metabolic adaptation to stressful and nutrient-limited environments, and also in the virulence of this strain towards the Caenorhabditis elegans infection model [43]. In addition to genes involved in nitrogen metabolism, other genes were activated by low nitrogen in a σ54-dependent manner, namely the two gene clusters involved in the biosynthesis of the exopolysaccharide Cepacian. Cepacian was previously shown to protect cells from external stresses, such as desiccation and metal ion stress [44], and also to be involved in pathogenic interactions [45,46], to interfere with the innate host immune system [45,47], being required for the formation of thick and mature biofilms [48]. Additionally, RpoN was also found to regulate genes involved in biofilm formation, motility, and virulence [43,49]. In B. cenocepacia K56-2, RpoN was shown to be important for the intracellular trafficking and survival of the bacteria within infected macrophages [49]. Unlike other alternative sigma factors, RpoN-dependent gene transcription initiation requires an enhancer binding protein that is often a response regulator belonging to a two-component regulatory system [49]. Despite the existence of 20 predicted enhancer binding proteins in B. cenocepacia, a mutant defect in one of these proteins (BCAL1536) exhibited an attenuated virulence in a rat agar bead infection model [50].

3.2. Quorum Sensing

Quorum sensing (QS) is a form of bacterial cell-to-cell communication that is mediated by the production of signaling molecules, called autoinducers [51]. The autoinducers accumulate outside the cell and once their concentration reaches a critical value (the threshold), specific receptors mediate the induction or repression of target gene expression [51]. The LuxIR homolog CepIR was the first QS system to be identified in a B. cenocepacia strain [52]. Since then, the CepIR was shown to be widespread in Bcc bacteria [53,54], being required for full virulence in Bcc infection models including C. elegans, Galleria mellonella, rodents, zebrafish, alfalfa, and onions [55,56,57]. The CepIR system relies on the acyl homoserine lactone (AHL) synthase CepI and the transcriptional regulator CepR that specifically binds to AHL becoming active. In its activated form, CepR binds to the cep boxes, located upstream specific genes, causing the induction or repression of their expression [51,54]. CepI synthesizes N-octanoylhomoserine lactone (C8-HSL) and, as a minor by-product, N-hexanoylhomoserine lactone (C6-HSL) as signalling molecules [51,54]. The CepIR system has been shown to be involved in the regulation of toxins, lipases, extracellular proteases, iron-chelating siderophores, antifungal agents, swarming motility, and biofilm formation (reviewed in [51,57,58,59]). In Burkholderia vietnamiensis, a N-decanoyl homoserine lactone (C10-HSL)-dependent QS system named BviIR, was also described [60].

A QS system based on the fatty acid molecule cis-2-dodecenoic acid as the signaling molecule was identified for the first time in B. cenocepacia J2315 and was named Burkholderia diffusible signal factor (BDSF) [61]. This molecule is used as the signaling molecule of the RpfFR QS system highly conserved within Bcc [62]. The RpfFR system relies on the biosynthesis of BDSF by the bifunctional crotonase RpfF and the BDSF receptor protein RpfR containing PAS-GGDEF-EAL domains [59]. The signaling molecule BDSF binds to RpfR, stimulating the cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP) phosphodiesterase activity of the protein, and thus lowering the intracellular c-di-GMP levels [63]. This QS system interferes with cell motility, biofilm formation, proteolytic activity, and virulence [59,63]. Several of the genes positively regulated by RpfFR are also controlled by the CepIR QS system [34]. However, the contribution of each of the QS systems to the regulation of target genes was found to be variable and their functions seem to be parallel [34]. Molecules of the DSF-family, including BDSF, are involved in interspecies and interkingdom communication [61,64]. Recently, molecules of this family were found in the sputum of CF patients, suggesting that bacterial interspecies communication mediated by DSF molecules can occur in the CF lung [65].

B. cenocepacia in particular has two additional QS systems: the AHL-type system CciIR (encoded on a genetic locus known as the B. cenocepacia island (cci) and found in ET12 lineage strains) [66] and the CepR2 [57]. The AHL synthase CciI synthesizes C6-HSL and, in minor amounts, C8-HSL that can be bound to the receptor CciR [66]. The CciIR and CepIR systems can interact with each other, with CciR negatively regulating cepI and CepR regulating positively cciI [66]. CepR2, an orphan LuxR homolog, was shown to act as an anti-activator of CepS, an AraC-type regulator, that activates gene expression in the absence of CepR2 [67].

Additional regulators affecting the QS circuitry in Bcc strains have been identified. For instance, the LysR-type transcriptional regulator ShvR (Shiny colony variants Regulator) was shown to negatively control cepIR and cciIR expression while positively affecting biofilm formation [68]. The membrane hybrid sensor kinase AtsR (Adhesion and type six secretion system Regulator) was shown to be a negative regulator of cepI and cciI expression [69]. Recently, AtsR was also shown to be a global regulator, controlling the expression of virulence factors in the absence of the CepIR QS system [70]. The upregulation of cepI in response to low oxygen concentration was found as independent of cell density [11]. However, the mechanism responsible for QS regulation under low concentration of oxygen remains unknown.

3.3. Iron Acquisition and Bcc Virulence

Iron is an essential element for living cells, it is present in cytochromes, ferredoxins, and other iron-containing proteins, and it is also a co-factor of several enzymes. When infecting mammalian hosts, bacterial pathogens face a shortage of iron, since this metal ion is bound to transferrin and lactoferrin. To fulfill their iron requirements, Bcc bacteria use metal chelator molecules named siderophores to capture and transport iron into the bacterial cell, using specialized receptors localized in the membrane. Therefore, although iron acquisition is not a virulence factor per se, systems used to acquire iron in the context of interaction with the host ultimately play a role in virulence. Several iron acquisition mechanisms by Bcc are known [71]. Bcc bacteria can produce up to four siderophores (ornibactin, pyochelin, cepabactin, and cepaciachelin), although evidence points out ornibactins as the most important [72]. A mutant in orbA, one of the three genes involved in ornibactin biosynthesis, was shown to be impaired in virulence in an animal model [73]. Genes for ornibactin synthesis and utilization were found as significantly upregulated when cells were exposed to iron limited availability [74]. Furthermore, data was also presented by these authors, indicating that iron acquisition during chronic lung infection is multifaceted, and B. cenocepacia has the ability to differentially activate the expression of genes for iron acquisition in the presence of the major CF pathogen and iron competitor Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Bcc bacteria are also endowed with iron acquisition mechanisms independent of siderophore production [71]. Whitby et al. [75] showed that B. cenocepacia J2315 uses ferritin in a protease-dependent manner. Several B. cenocepacia strains are also able to use hemin as an iron source [74,76]. Heme is a component of hemoglobin and the most abundant iron source in the host body. Therefore, Bcc strains that produce hemolysins can have access to this source of iron. Using ram erythrocytes, Bevivino et al., (2002) [77] found that the majority of the Burkholderia ambifaria isolates tested were hemolytic. However, the percentage of hemolytic B. cenocepacia isolates from environmental sources was higher than those of clinical origin. Hutchison et al. (1998) identified a lipopeptide secreted by B. cenocepacia capable of erythrocyte hemolysis [78]. Thomson and Dennis (2012) [79] identified a gene cluster involved in the expression of a toxin with β-hemolytic activity required for full virulence of Bcc in the Galeria mellonella model of infection. The toxin was shown to be synthesized via a non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) mechanism. However, in this study, production of NRPS-derived occidiofungin/burkholdine-like compounds was shown to be limited to B. ambifaria, B. contaminans, B. pyrrocinia, and B. vietnamiensis. The fact that this toxin was not found in the most common clinical Bcc species, B. cenocepacia and B. multivorans, suggested to the authors that this gene cluster evolved to protect Bcc bacteria from ecological niche predators such as amoeba and fungi [79].

3.4. Activators and Repressors

Adaptive responses are commonly mediated by transcriptional regulators. In most of the cases, the regulators involved in transcriptional control are two-domain proteins with a signal receiving domain and a DNA-binding domain which transduces the signal [80]. The bioinformatics analysis of Bcc genome sequences revealed several genes putatively codifying for various families of transcriptional regulators, including the AraC, ArsR, AsnC, DeoR, GntR, IcIR, LacI, LysR, MarR, MerR, and TetR families [81]. However, only a few were already functionally characterized.

For instance, the LysR-type transcriptional regulator, ShvR, was shown to regulate over 1000 genes, affecting Bcc colony morphology, biofilm formation, virulence in plant and animal infection models, and some quorum-sensing-dependent phenotypes [68,82,83]. In particular, ShvR downregulates the expression of cepIR and cccIR, type II secretion system, proteases, and lipases [82]. In addition, ShvR is an inducer of biofilm formation and of rough colony morphology in a CepR-independent mechanism [82]. ShvR was also shown to directly regulate the expression of the promoters of afcA and afcC genes required for the production of an antifungal agent [82]. Subramoni and colleagues [84] have shown that ShvR also regulates afcE and afcF encoding an acyl-CoA dehydrogenase and a Flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)-dependent oxidoreductase, respectively. In their work, these authors have also shown that these two proteins are required for the synthesis of a membrane-associated antifungal lipopeptide, affecting the membrane morphology and permeability, the surface motility, and the total cellular lipid composition. The shvR expression is positively-regulated by CepIR and CciIR in a feedback loop of regulation [32].Recently, a novel transcriptional regulator, named BcRsaM was identified in Bcc [85]. BcRsaM was postulated to be involved in the modulation of CepI abundance and CepR activity [85].

3.5. Two-Component Regulatory Systems

Two-component regulatory systems (TCSs) are composed by two proteins, a membrane-bound histidine kinase that receives the environmental stimuli and autophosphorylates and then transfers the phosphate to a cytoplasmic DNA-binding response regulator that mediates changes in gene expression [86].

The bioinformatics analysis of Bcc genome sequences revealed at least 28 putative two-component systems, however only a few are already functionally characterized [81]. Recently, the B. cenocepacia K56-2 BceSR regulatory system was described [87]. A bceR mutant exhibited a decreased protease production, quorum sensing, and swimming motility, and reduced virulence in the alfalfa plant model [87]. Bioinformatics analysis of other Bcc genome sequences revealed that the BceSR system is also present in B. ambifaria, B. multivorans, B. vietnamiensis, and B. dolosa [87]. A novel TCS was recently identified in B. cenocepacia and was named esaSR [88]. The deletion of the response regulator esaR caused the sensibility of B. cenocepacia to carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, kanamycin, meropenem, novobiocin, and tetracycline [88]. This mutation also led to a defect in the membrane integrity [88].

The AtsR/AtsT phosphorelay pathway was shown to be a major global regulator of B. cenocepacia pathogenicity [70]. This mechanism was shown to negatively regulate quorum sensing, biofilm production, type VI secretion system (T6SS), and protease secretion [70]. Deletion of atsR was shown to cause a significant increase in T6SS activity that induces actin cytoskeletal rearrangements of infected macrophages and delay the assembly of the NADPH oxidase complex at the membrane of the B. cenocepacia-containing vacuole [89]. Flanagan and colleagues [90] identified a six-gene cluster encoding a TCS (BCAL2831 and BCAL2830) and an HtrA protease (BCAL2829). Mutation of the BCAL2831 affected the gene cluster transcription, revealing that the encoding proteins are required for osmotic and prolonged heat stress and for survival in a rat model of chronic lung infection [90]. The lack of complementation of the BCAL2831 mutation by expression of the High temperature requirement A (HtrA) protease revealed that the TCS identified could regulate the genes required for growth under stress conditions and for survival in vivo [90].Recently, the oxygen-sensing two-component regulatory system FixLJ was identified in B. dolosa as being involved in the regulation of motility, biofilm formation, intracellular invasion of macrophages, and virulence [91].

3.6. Toxin-Antitoxin

A total of 16 toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems were recently identified in the B. cenocepacia J2315 genome, with only 9 of them common to other Bcc strains [37]. Bacterial TA loci consist of two genes, one encoding a potentially toxic protein, and the other encoding an antitoxin that represses the toxin function or expression [92]. The antitoxin can be either a protein or a RNA. TA systems from other bacterial species have been described as regulators of biofilm formation, programmed cell death or inhibition of cell growth, stabilization of mobile genetic elements, and persistence [93]. The upregulation of toxin-antitoxin genes in the adaptation process to growth arrest caused by both stationary phase and low-oxygen conditions was reported based on transcriptomics methodologies [11].

In B. cenocepacia, the overexpression of seven of these toxins (BCAL0610, BCAM0272, BCAM0627, BCAS0580, pBCA093, BCAL0070, and BCAL3209) led to the development of persister cells after exposure to ciprofloxacin or tobramycin [37]. A correlation between the growth delay and the development of persister cells was observed. The overexpression of some toxins also led to alterations in biofilm formation [37]. Therefore, the expression of TA systems was compared in antibiotic-treated and untreated planktonic and sessile cultures. This comparison showed that the expression of nine toxin-encoding genes was higher after treatment with tobramycin. However, no changes occurred after treatment with ciprofloxacin, revealing that specific TA modules contribute to B. cenocepacia persistence, as their upregulation is specifically dependent on the mode of growth of the bacterium and of the antibiotic used [37].

3.7. sRNA and Hfq

When comparing the transcriptome of two related strains of B. cenocepacia (of clinical and environmental origins) under conditions that mimic CF sputum versus soil, Yoder-Himes et al. [31] noticed that a high number of transcripts induced in B. cenocepacia J2315 originated from intergenic regions. This observation indicates that the identified transcripts are either non-coding RNAs (sRNAs) or unannotated genes that encode for mRNAs. sRNAs are bacterial key posttranscriptional regulators of gene expression affecting a wide range of cellular processes, including virulence in several bacterial pathogens (reviewed in [94,95]). A large class of sRNAs exert their regulatory action by base pairing with specific mRNAs (the mRNA targets) with the help of the RNA chaperone Hfq. The sRNA-mRNA double stranded complex often hinders the ribosome binding site (RBS) of the mRNA, leading to repression of gene expression [96]. In a few cases, the double-stranded complex exposes the RBS of the mRNA, resulting in increased expression of the encoded protein [96].

In a bioinformatics study, Coenye et al. [28] identified 213 putative sRNAs on the genome of the highly epidemic clinical isolate B. cenocepacia J2315, although the authors have only confirmed the expression of four of these sRNAs. The comparison of the transcriptional responses of B. cenocepacia J2315 growing as planktonic or sessile upon exposure to chlorhexidine also revealed that 19 intergenic (IG) sequences putatively encoding sRNAs were differentially expressed, suggesting a putative role of these sRNA on chlorhexidine tolerance [39]. However, their biological function remains unknown. Several IG were also shown to be differentially expressed by sessile cells of B. cenocepacia J2315 subject to oxidative stress [36].

The Hfq protein is an RNA chaperone that mediates interactions between sRNAs and their target mRNAs, playing an important role as a global regulator of bacterial metabolism and virulence (recently reviewed in [96,97]). Together with a few other prokaryotes, Bcc bacteria encode in their genomes two distinct and functional Hfq-like proteins, hfq and hfq2 genes [98]. A co-purification experiment of the RNA binding Hfq protein and total RNA from B. cenocepacia J2315 led to the identification and validation of 24 novel sRNAs, not previously identified by transcriptomics or bioinformatics studies [99]. The cis-encoded h2cR and the trans-encoded MtvR sRNAs remain as the few Bcc sRNAs functionally characterized [100,101]. The h2cR sRNA was shown to negatively regulate hfq2 mRNA by binding to the 5′-UTR region of the hfq2 mRNA, leading to an accelerated decay of hfq2 mRNA and reduced protein levels in exponentially growing cells [100]. MtvR was described as conserved in Bcc, acting as a global regulator affecting bacterial growth, motility, biofilm formation, virulence, and resistance to stress and antibiotics [101].

A recent study based on a genome-wide mapping of transcription start sites of biofilm-grown B. cenocepacia J2315 revealed that 15 non-coding sRNAs were highly expressed under those conditions [38]. Homologs to 9 out of these 15 putative non-coding sRNAs were found in the RFAM database. Interestingly, four of these sRNA belong to the new ‘toxic sRNAs’ family, known due to their toxicity when overexpressed in E. coli. Their presence in the genomes of four strains of B. cenocepacia was confirmed by Northern-blot [102]. Expression of the other six non-coding sRNAs was previously experimentally confirmed [30,99], but their function, as for most of the Bcc sRNAs, is still unknown.

4. Conclusions

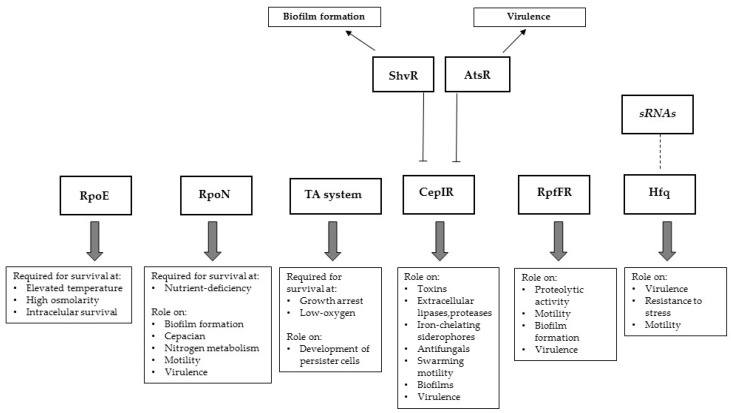

The recent use of high-throughput sequencing and “omics” strategies sheds new light on the mechanisms used by Bcc bacteria to adapt to the CF lung. From the still-limited comparative genomics studies performed using Bcc serial isolates, the emerging picture is that adaptive mutations lead to the co-evolution of multiple lineages in the CF lung. Genes identified as subject to a strong in vivo selection include those involved in antibiotic resistance, adaptation to low oxygen, iron acquisition, adaptation to the biofilm lifestyle, and adherence to the respiratory epithelial surface. Transcriptomics studies also point out differentially expressed genes involved in adaptation to low oxygen availability, transport and efflux systems, quorum sensing, exopolysaccharide, and flagella biosynthesis, as a result of lung adaptation. These mechanisms include the sensing of alterations in the environment during the infection process and the use of a combination of regulatory systems to survive in the host (Figure 1). This complex pattern of regulatory interplay between diverse regulatory mechanisms is only emerging and new data expected to contribute to our understanding of Bcc infections will certainly be revealed in the near future.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc) regulators that emerged as involved in virulence and other phenotypes based on transcriptomics studies using bacteria infecting cystic fibrosis (CF) patients or cultivated under conditions mimicking the CF lung environment. Despite the description of several sRNAs actively involved in Bcc virulence, their specific function remains to be fully characterized and therefore a dashed-line linking sRNAs and Hfq was used.

Acknowledgments

Funding received by iBB-Institute for Bioengineering and Biosciences from FCT-Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (UID/BIO/04565/2013) and from Programa Operacional Regional de Lisboa 2020 (Project N. 007317) is acknowledged. This work was also partially funded by FCT, Portugal (contract PTDC/BIA-MIC/1615/2014), and grants to SAS (SFRH/BPD/102006/2014), JRF, and TP.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The founding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

References

- 1.Holden M.T., Seth-Smith H.M., Crossman L.C., Sebaihia M., Bentley S.D., Cerdeno-Tarraga A.M., Thomson N.R., Bason N., Quail M.A., Sharp S., et al. The Genome of Burkholderia cenocepacia J2315, an Epidemic Pathogen of Cystic Fibrosis Patients. J. Bacteriol. 2009;191:261–277. doi: 10.1128/JB.01230-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ussery D.W., Kiil K., Lagesen K., Sicheritz-Pont-eacuten T., Bohlin J., Wassenaar T.M. Microbial Pathogenomics. Volume 6. KARGER; Basel, Switzerland: 2009. The Genus Burkholderia: Analysis of 56 Genomic Sequences; pp. 140–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Depoorter E., Bull M.J., Peeters C., Coenye T., Vandamme P., Mahenthiralingam E. Burkholderia: An update on taxonomy and biotechnological potential as antibiotic producers. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016;100:5215–5229. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7520-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahenthiralingam E., Urban T.A., Goldberg J.B. The multifarious, multireplicon Burkholderia cepacia complex. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005;3:144–156. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leitão J.H., Sousa S.A., Ferreira A.S., Ramos C.G., Silva I.N., Moreira L.M. Pathogenicity, virulence factors, and strategies to fight against Burkholderia cepacia complex pathogens and related species. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;87:31–40. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2528-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lipuma J.J. The changing microbial epidemiology in cystic fibrosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010;23:299–323. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00068-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leitão J.H., Sousa S.A., Cunha M.V., Salgado M.J., Melo-Cristino J., Barreto M.C., Sá-Correia I. Variation of the antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of Burkholderia cepacia complex clonal isolates obtained from chronically infected cystic fibrosis patients: A five-year survey in the major Portuguese treatment center. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2008;27:1101–1111. doi: 10.1007/s10096-008-0552-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones A.M., Dodd M.E., Webb A.K. Burkholderia cepacia: Current clinical issues, environmental controversies and ethical dilemmas. Eur. Respir. J. 2001;17:295–301. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.17202950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loutet S.A., Valvano M.A. A decade of Burkholderia cenocepacia virulence determinant research. Infect. Immun. 2010;78:4088–4100. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00212-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang L., Jelsbak L., Molin S. Microbial ecology and adaptation in cystic fibrosis airways. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;13:1682–1689. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sass A.M., Schmerk C., Agnoli K., Norville P.J., Eberl L., Valvano M.A., Mahenthiralingam E. The unexpected discovery of a novel low-oxygen-activated locus for the anoxic persistence of Burkholderia cenocepacia. ISME J. 2013;14:1–14. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saldías M.S., Valvano M.A. Interactions of Burkholderia cenocepacia and other Burkholderia cepacia complex bacteria with epithelial and phagocytic cells. Microbiology. 2009;155:2809–2817. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.031344-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lieberman T.D., Michel J.-B., Aingaran M., Potter-Bynoe G., Roux D., Davis M.R., Skurnik D., Leiby N., LiPuma J.J., Goldberg J.B., et al. Parallel bacterial evolution within multiple patients identifies candidate pathogenicity genes. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:1275–1280. doi: 10.1038/ng.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lieberman T.D., Flett K.B., Yelin I., Martin T.R., McAdam A.J., Priebe G.P., Kishony R. Genetic variation of a bacterial pathogen within individuals with cystic fibrosis provides a record of selective pressures. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:82–87. doi: 10.1038/ng.2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silva I.N., Santos P.M., Santos M.R., Zlosnik J.E.A., Speert D.P., Buskirk S.W., Bruger E.L., Waters C.M., Cooper V.S., Moreira L.M. Long-Term Evolution of Burkholderia multivorans during a Chronic Cystic Fibrosis Infection Reveals Shifting Forces of Selection. mSystems. 2016;1 doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00029-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nunvar J., Kalferstova L., Bloodworth R.A.M., Kolar M., Degrossi J., Lubovich S., Cardona S.T., Drevinek P., Bevivino A. Understanding the Pathogenicity of Burkholderia contaminans, an Emerging Pathogen in Cystic Fibrosis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0160975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mira N.P., Madeira A., Moreira A.S., Coutinho C.P., Sá-Correia I. Genomic Expression Analysis Reveals Strategies of Burkholderia cenocepacia to Adapt to Cystic Fibrosis Patients’ Airways and Antimicrobial Therapy. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sass A., Marchbank A., Tullis E., Lipuma J.J., Mahenthiralingam E. Spontaneous and evolutionary changes in the antibiotic resistance of Burkholderia cenocepacia observed by global gene expression analysis. BMC Genom. 2011;12:373. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalferstova L., Kolar M., Fila L., Vavrova J., Drevinek P. Gene expression profiling of Burkholderia cenocepacia at the time of cepacia syndrome: Loss of motility as a marker of poor prognosis? J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015;53:1515–1522. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03605-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith E.E., Buckley D.G., Wu Z., Saenphimmachak C., Hoffman L.R., D’Argenio D.A., Miller S.I., Ramsey B.W., Speert D.P., Moskowitz S.M., et al. Genetic adaptation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the airways of cystic fibrosis patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:8487–8492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602138103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deitsch K.W., Lukehart S.A., Stringer J.R. Common strategies for antigenic variation by bacterial, fungal and protozoan pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:493–503. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rau M.H., Hansen S.K., Johansen H.K., Thomsen L.E., Workman C.T., Nielsen K.F., Jelsbak L., Høiby N., Yang L., Molin S. Early adaptive developments of Pseudomonas aeruginosa after the transition from life in the environment to persistent colonization in the airways of human cystic fibrosis hosts. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;12:1643–1658. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crosson S., McGrath P.T., Stephens C., McAdams H.H., Shapiro L. Conserved modular design of an oxygen sensory/signaling network with species-specific output. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:8018–8023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503022102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Worlitzsch D., Tarran R., Ulrich M., Schwab U., Cekici A., Meyer K.C., Birrer P., Bellon G., Berger J., Weiss T., et al. Effects of reduced mucus oxygen concentration in airway Pseudomonas infections of cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Investig. 2002;109:317–325. doi: 10.1172/JCI0213870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Govan J.R., Brown A.R., Jones A.M. Evolving epidemiology of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the Burkholderia cepacia complex in cystic fibrosis lung infection. Future Microbiol. 2007;2:153–164. doi: 10.2217/17460913.2.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martina P., Feliziani S., Juan C., Bettiol M., Gatti B., Yantorno O., Smania A.M., Oliver A., Bosch A. Hypermutation in Burkholderia cepacia complex is mediated by DNA mismatch repair inactivation and is highly prevalent in cystic fibrosis chronic respiratory infection. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2014;304:1182–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oliver A., Mena A. Bacterial hypermutation in cystic fibrosis, not only for antibiotic resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2010;16:798–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coenye T., Drevinek P., Mahenthiralingam E., Shah S.A., Gill R.T., Vandamme P., Ussery D.W. Identification of putative noncoding RNA genes in the Burkholderia cenocepacia J2315 genome. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2007;276:83–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drevinek P., Holden M.T.G., Ge Z., Jones A.M., Ketchell I., Gill R.T., Mahenthiralingam E. Gene expression changes linked to antimicrobial resistance, oxidative stress, iron depletion and retained motility are observed when Burkholderia cenocepacia grows in cystic fibrosis sputum. BMC Infect. Dis. 2008;8:121. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoder-Himes D.R., Chain P.S.G., Zhu Y., Wurtzel O., Rubin E.M., Tiedje J.M., Sorek R. Mapping the Burkholderia cenocepacia niche response via high-throughput sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:3976–3981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813403106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoder-Himes D.R., Konstantinidis K.T., Tiedje J.M. Identification of potential therapeutic targets for Burkholderia cenocepacia by comparative transcriptomics. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e8724. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Grady E.P., Viteri D.F., Malott R.J., Sokol P.A. Reciprocal regulation by the CepIR and CciIR quorum sensing systems in Burkholderia cenocepacia. BMC Genom. 2009;10:441. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inhülsen S., Aguilar C., Schmid N., Suppiger A., Riedel K., Eberl L. Identification of functions linking quorum sensing with biofilm formation in Burkholderia cenocepacia H111. Microbiologyopen. 2012;1:225–242. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmid N., Pessi G., Deng Y., Aguilar C., Carlier A.L., Grunau A., Omasits U., Zhang L.H., Ahrens C.H., Eberl L. The AHL- and BDSF-Dependent Quorum Sensing Systems Control Specific and Overlapping Sets of Genes in Burkholderia cenocepacia H111. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e49966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bazzini S., Udine C., Sass A., Pasca M.R., Longo F., Emiliani G., Fondi M., Perrin E., Decorosi F., Viti C., et al. Deciphering the role of rnd efflux transporters in Burkholderia cenocepacia. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e18902. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peeters E., Sass A., Mahenthiralingam E., Nelis H., Coenye T. Transcriptional response of Burkholderia cenocepacia J2315 sessile cells to treatments with high doses of hydrogen peroxide and sodium hypochlorite. BMC Genom. 2010;11:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Acker H., Sass A., Dhondt I., Nelis H.J., Coenye T. Involvement of toxin-antitoxin modules in Burkholderia cenocepacia biofilm persistence. Pathog. Dis. 2014;71:326–335. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sass A.M., van Acker H., Förstner K.U., van Nieuwerburgh F., Deforce D., Vogel J., Coenye T. Genome-wide transcription start site profiling in biofilm-grown Burkholderia cenocepacia J2315. BMC Genom. 2015;16:775. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1993-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coenye T., van Acker H., Peeters E., Sass A., Buroni S., Riccardi G., Mahenthiralingam E. Molecular mechanisms of chlorhexidine tolerance in Burkholderia cenocepacia biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1912–1919. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01571-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Menard A., de los Santos P.E., Arnault Graindorge V., Cournoyer B., Genomics B., Cournoyer A. Architecture of Burkholderia cepacia complex sigma 70 gene family: Evidence of alternative primary and clade-specific factors, and genomic instability Architecture 70 alternative. BMC Genom. 2007;8:308. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raina S., Missiakas D., Georgopoulos C. The rpoE gene encoding the sigma E (sigma 24) heat shock sigma factor of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1995;14:1043–1055. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07085.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flannagan R.S., Valvano M.A. Burkholderia cenocepacia requires RpoE for growth under stress conditions and delay of phagolysosomal fusion in macrophages. Microbiology. 2008;154:643–653. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/013714-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lardi M., Aguilar C., Pedrioli A., Omasits U., Suppiger A., Cárcamo-Oyarce G., Schmid N., Ahrens C.H., Eberl L., Pessi G. σ54-Dependent Response to Nitrogen Limitation and Virulence in Burkholderia cenocepacia Strain H111. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015;81:4077–4089. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00694-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferreira A.S., Leitão J.H., Silva I.N., Pinheiros P.F., Sousa S.A., Ramos C.G., Moreira L.M. Distribution of cepacian biosynthesis genes among environmental and clinical Burkholderia strains and role of cepacian exopolysaccharide in resistance to stress conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:441–450. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01828-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Conway B.-A.D., Chu K.K., Bylund J., Altman E., Speert D.P. Production of exopolysaccharide by Burkholderia cenocepacia results in altered cell-surface interactions and altered bacterial clearance in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 2004;190:957–966. doi: 10.1086/423141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sousa S.A., Ulrich M., Bragonzi A., Burke M., Worlitzsch D., Leitão J.H., Meisner C., Eberl L., Sá-correia I., Döring G. Virulence of Burkholderia cepacia complex strains in gp91phox-/-mice. Cell. Microbiol. 2007;9:2817–2825. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bylund J., Burgess L.-A., Cescutti P., Ernst R.K., Speert D.P. Exopolysaccharides from Burkholderia cenocepacia inhibit neutrophil chemotaxis and scavenge reactive oxygen species. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:2526–2532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510692200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cunha M.V., Sousa S.A., Leitão J.H., Moreira L.M., Videira P.A., Sá-Correia I. Studies on the involvement of the exopolysaccharide produced by cystic fibrosis-associated isolates of the Burkholderia cepacia complex in biofilm formation and in persistence of respiratory infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42:3052–3058. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.7.3052-3058.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saldías M.S., Lamothe J., Wu R., Valvano M.A. Burkholderia cenocepacia requires the RpoN sigma factor for biofilm formation and intracellular trafficking within macrophages. Infect. Immun. 2008;76:1059–1067. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01167-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hunt T.A., Kooi C., Sokol P.A., Valvano M.A. Identification of Burkholderia cenocepacia genes required for bacterial survival in vivo. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:4010–4022. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.4010-4022.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eberl L. Quorum sensing in the genus Burkholderia. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2006;296:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2006.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lewenza S., Conway B., Greenberg E.P., Sokol P.A. Quorum sensing in Burkholderia cepacia: Identification of the LuxRI homologs CepRI. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:748–756. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.3.748-756.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gotschlich A., Huber B., Geisenberger O., Tögl A., Steidle A., Riedel K., Hill P., Tümmler B., Vandamme P., Middleton B., et al. Synthesis of Multiple N-Acylhomoserine Lactones is Wide-spread Among the Members of the Burkholderia cepacia Complex. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2001;24:1–14. doi: 10.1078/0723-2020-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lutter E., Lewenza S., Dennis J.J., Visser M.B., Sokol P.A. Distribution of Quorum-Sensing Genes in the Burkholderia cepacia Complex. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:4661–4666. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4661-4666.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uehlinger S., Schwager S., Bernier S.P., Riedel K., Nguyen D.T., Sokol P.A., Eberl L. Identification of specific and universal virulence factors in Burkholderia cenocepacia strains by using multiple infection hosts. Infect. Immun. 2009;77:4102–4110. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00398-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sokol P.A., Sajjan U., Visser M.B., Gingues S., Forstner J., Kooi C. The CepIR quorum-sensing system contributes to the virulence of Burkholderia cenocepacia respiratory infections. Microbiology. 2003;149:3649–3658. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26540-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Subramoni S., Sokol P.A. Quorum sensing systems influence Burkholderia cenocepacia virulence. Future Microbiol. 2012;7:1373–1387. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Venturi V., Friscina A., Bertani I., Devescovi G., Aguilar C. Quorum sensing in the Burkholderia cepacia complex. Res. Microbiol. 2004;155:238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suppiger A., Schmid N., Aguilar C., Pessi G., Eberl L. Two quorum sensing systems control biofilm formation and virulence in members of the Burkholderia cepacia complex. Virulence. 2013;4:400–409. doi: 10.4161/viru.25338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Conway B.-A., Greenberg E.P. Quorum-sensing signals and quorum-sensing genes in Burkholderia vietnamiensis. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:1187–1191. doi: 10.1128/jb.184.4.1187-1191.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boon C., Deng Y., Wang L.-H., He Y., Xu J.-L., Fan Y., Pan S.Q., Zhang L.-H. A novel DSF-like signal from Burkholderia cenocepacia interferes with Candida albicans morphological transition. ISME J. 2008;2:27–36. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Deng Y., Wu J., Eberl L., Zhang L.-H. Structural and Functional Characterization of Diffusible Signal Factor Family Quorum-Sensing Signals Produced by Members of the Burkholderia cepacia Complex. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:4675–4683. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00480-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Deng Y., Schmid N., Wang C., Wang J., Pessi G., Wu D., Lee J., Aguilar C., Ahrens C.H., Chang C., et al. Cis-2-dodecenoic acid receptor RpfR links quorum-sensing signal perception with regulation of virulence through cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate turnover. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:15479–15484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205037109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ryan R.P., Dow J.M. Communication with a growing family: Diffusible signal factor (DSF) signaling in bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2011;19:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Twomey K.B., O’Connell O.J., McCarthy Y., Dow J.M., O’Toole G.A., Plant B.J., Ryan R.P. Bacterial cis-2-unsaturated fatty acids found in the cystic fibrosis airway modulate virulence and persistence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. ISME J. 2012;6:939–950. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Malott R.J., Baldwin A., Mahenthiralingam E., Sokol P.A. Characterization of the cciIR Quorum-Sensing System in Burkholderia cenocepacia. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:4982–4992. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.8.4982-4992.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ryan G.T., Wei Y., Winans S.C. A LuxR-type repressor of Burkholderia cenocepacia inhibits transcription via antiactivation and is inactivated by its cognate acylhomoserine lactone. Mol. Microbiol. 2013;87:94–111. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bernier S.P., Nguyen D.T., Sokol P.A. A LysR-type transcriptional regulator in Burkholderia cenocepacia influences colony morphology and virulence. Infect. Immun. 2008;76:38–47. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00874-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aubert D.F., O’Grady E.P., Hamad M.A., Sokol P.A., Valvano M.A. The Burkholderia cenocepacia sensor kinase hybrid AtsR is a global regulator modulating quorum-sensing signalling. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;15:372–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Khodai-Kalaki M., Aubert D.F., Valvano M.A. Characterization of the AtsR hybrid sensor kinase phosphorelay pathway and identification of its response regulator in Burkholderia cenocepacia. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:30473–30484. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.489914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thomas M.S. Iron acquisition mechanisms of the Burkholderia cepacia complex. BioMetals. 2007;20:431–452. doi: 10.1007/s10534-006-9065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Visser M.B., Majumdar S., Hani E., Sokol P.A. Importance of the ornibactin and pyochelin siderophore transport systems in Burkholderia cenocepacia lung infections. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:2850–2857. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.5.2850-2857.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sokol P.A., Darling P., Lewenza S., Corbett C.R., Kooi C.D. Identification of a siderophore receptor required for ferric ornibactin uptake in Burkholderia cepacia. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:6554–6560. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.12.6554-6560.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tyrrell J., Whelan N., Wright C., Sá-Correia I., McClean S., Thomas M., Callaghan M. Investigation of the multifaceted iron acquisition strategies of Burkholderia cenocepacia. BioMetals. 2015;28:367–380. doi: 10.1007/s10534-015-9840-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Whitby P.W., VanWagoner T.M., Springer J.M., Morton D.J., Seale T.W., Stull T.L. Burkholderia cenocepacia utilizes ferritin as an iron source. J. Med. Microbiol. 2006;55:661–668. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46199-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mathew A., Eberl L., Carlier A.L. A novel siderophore-independent strategy of iron uptake in the genus Burkholderia. Mol. Microbiol. 2014;91:805–820. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bevivino A., Dalmastri C., Tabacchioni S., Chiarini L., Belli M.L., Piana S., Materazzo A., Vandamme P., Manno G. Burkholderia cepacia complex bacteria from clinical and environmental sources in Italy: Genomovar status and distribution of traits related to virulence and transmissibility. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002;40:846–851. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.3.846-851.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hutchison M.L., Poxton I.R., Govan J.R. Burkholderia cepacia produces a hemolysin that is capable of inducing apoptosis and degranulation of mammalian phagocytes. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:2033–2039. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2033-2039.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thomson E.L.S., Dennis J.J. A Burkholderia cepacia complex non-ribosomal peptide-synthesized toxin is hemolytic and required for full virulence. Virulence. 2012;3:286–298. doi: 10.4161/viru.19355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ramos J.L., Martínez-Bueno M., Molina-Henares A.J., Terán W., Watanabe K., Zhang X., Gallegos M.T., Brennan R., Tobes R. The TetR family of transcriptional repressors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2005;69:326–356. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.2.326-356.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Winsor G.L., Khaira B., van Rossum T., Lo R., Whiteside M.D., Brinkman F.S.L. The Burkholderia Genome Database: Facilitating flexible queries and comparative analyses. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2803–2804. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.O’Grady E.P., Nguyen D.T., Weisskopf L., Eberl L., Sokol P.A. The Burkholderia cenocepacia LysR-type transcriptional regulator ShvR influences expression of quorum-sensing, protease, type II secretion, and afc genes. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:163–176. doi: 10.1128/JB.00852-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Thomson E.L.S., Dennis J.J. Common duckweed (Lemna minor) is a versatile high-throughput infection model for the Burkholderia cepacia complex and other pathogenic bacteria. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e80102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Subramoni S., Agnoli K., Eberl L., Lewenza S., Sokol P.A. Role of Burkholderia cenocepacia afcE and afcF genes in determining lipid-metabolism-associated phenotypes. Microbiology. 2013;159:603–614. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.064683-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Michalska K., Chhor G., Clancy S., Jedrzejczak R., Babnigg G., Winans S.C., Joachimiak A. RsaM: A transcriptional regulator of Burkholderia spp. with novel fold. FEBS J. 2014;281:4293–4306. doi: 10.1111/febs.12868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stock A.M., Robinson V.L., Goudreau P.N. Two-Component Signal Transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000;69:183–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Merry C.R., Perkins M., Mu L., Peterson B.K., Knackstedt R.W., Weingart C.L. Characterization of a Novel Two-Component System in Burkholderia cenocepacia. Curr. Microbiol. 2015;70:556–561. doi: 10.1007/s00284-014-0744-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gislason A.S., Choy M., Bloodworth R.A.M., Qu W., Stietz M.S., Li X., Zhang C., Cardona S.T. Competitive growth enhances conditional growth mutant sensitivity to antibiotics and exposes a two-component system as an emerging antibacterial target in Burkholderia cenocepacia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016;61:E00790-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00790-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Aubert D.F., Valvano M.A., Hu S. Quantification of type VI secretion system activity in macrophages infected with Burkholderia cenocepacia. Microbiology. 2015;161:2161–2173. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Flannagan R.S., Aubert D., Kooi C., Sokol P.A., Valvano M.A. Burkholderia cenocepacia requires a periplasmic HtrA protease for growth under thermal and osmotic stress and for survival in vivo. Infect. Immun. 2007;75:1679–1689. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01581-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schaefers M.M., Liao T.L., Boisvert N.M., Roux D., Yoder-Himes D., Priebe G.P. An Oxygen-Sensing Two-Component System in the Burkholderia cepacia Complex Regulates Biofilm, Intracellular Invasion, and Pathogenicity. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006116. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wen J., Fozo E. sRNA Antitoxins: More than One Way to Repress a Toxin. Toxins. 2014;6:2310–2335. doi: 10.3390/toxins6082310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lobato-Márquez D., Díaz-Orejas R., García-del Portillo F. Toxin-antitoxins and bacterial virulence. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2016;40:592–609. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuw022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gottesman S. Micros for microbes: Non-coding regulatory RNAs in bacteria. Trends Genet. 2005;21:399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Papenfort K., Vogel J. Regulatory RNA in Bacterial Pathogens. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:116–127. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Feliciano J.R., Grilo A.M., Guerreiro S.I., Sousa S.A., Leitão J.H. Hfq: A multifaceted RNA chaperone involved in virulence. Future Microbiol. 2016;11:137–151. doi: 10.2217/fmb.15.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Updegrove T.B., Zhang A., Storz G. Hfq: The flexible RNA matchmaker. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2016;30:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sousa S.A., Ramos C.G., Moreira L.M., Leitão J.H. The hfq gene is required for stress resistance and full virulence of Burkholderia cepacia to the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Microbiology. 2010;156:896–908. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.035139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ramos C.G., Grilo A.M., da Costa P.J.P., Leitão J.H. Experimental identification of small non-coding regulatory RNAs in the opportunistic human pathogen Burkholderia cenocepacia J2315. Genomics. 2013;101:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ramos C.G., da Costa P.J.P., Döring G., Leitão J.H. The Novel Cis-Encoded Small RNA h2cR Is a Negative Regulator of hfq2 in Burkholderia cenocepacia. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e47896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ramos C.G., Grilo A.M., Sousa S.A., Feliciano J.R., Da Costa P.J.P., Leitão J.H. Regulation of Hfq mRNA and protein levels in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa by the Burkholderia cenocepacia MtvR sRNA. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e98813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kimelman A., Levy A., Sberro H., Kidron S., Leavitt A., Amitai G., Yoder-Himes D.R., Wurtzel O., Zhu Y., Rubin E.M., et al. A vast collection of microbial genes that are toxic to bacteria. Genome Res. 2012;22:802–809. doi: 10.1101/gr.133850.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]