Abstract

Wasting and underweight reflect poor nutrition, which in children leads to retarded growth. The aim of this study is to determine the factors associated with wasting and underweight among children aged 0–59 months in Nigeria. A sample of 24,529 children aged 0–59 months from the 2013 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) was used. Multilevel logistic regression analysis that adjusted for cluster and survey weights was used to identify significant factors associated with wasting/severe wasting and underweight/severe underweight. The prevalence of wasting was 18% (95% Confidence Interval (CI): 17.1, 19.7) and severe wasting 9% (95% CI: 7.9, 9.8). The prevalence of underweight was 29% (95% CI: 27.1, 30.5) and severe underweight 12% (95% CI: 10.6, 12.9). Multivariable analysis revealed that the most consistent factors associated with wasting/severe wasting and underweight/severe underweight are: geopolitical zone (North East, North West and North Central), perceived birth size (small and average), sex of child (male), place/mode of delivery (home delivery and non-caesarean) and a contraction of fever in the two weeks prior to the survey. In order to meet the WHO’s global nutrition target for 2025, interventions aimed at improving maternal health and access to health care services for children especially in the northern geopolitical zones of Nigeria are urgently needed.

Keywords: wasting, underweight, Nigeria, public health, malnutrition, multilevel analysis

1. Introduction

Malnutrition is a major public health problem faced by children under five years as it inhibits their cognitive and physical development as well as contributes to child morbidity and mortality [1]. Malnutrition is linked to poverty, low levels of education, poor access to health services and presence of infections. Protein-energy malnutrition (PEM) is the most common form of malnutrition and results from deficiencies in energy and protein intake. Stunting, wasting and underweight are expressions of PEM. These malnutrition indicators are caused by an extremely low energy and protein intake, nutrient losses due to infection, or a combination of both low energy/protein intake and high nutrient loss by the mother during pregnancy or by the child after birth [2].

The global prevalence for wasting and underweight decreased from 9% and 25% in 1990 to 8% and 14% in 2015, respectively [3]. Regionally, Africa and South Asia reported the highest rate of child malnutrition in the world accounting for about one third of all undernourished children globally. In Africa, 9.4% of children under-five years were wasted while 23.5% were underweight [3]. However, despite the global decrease, wasting and underweight in Nigeria have been on the rise in the past 10 years, with wasting increasing from 11% in 2003 to 18% in 2013 and underweight from 24% in 2003 to 29% in 2013 [4], as opposed to stunting, which, though a malnutrition indicator, has reported a decrease in Nigeria from 42% in 2003 to 37% in 2013 and globally by 37% between 1990 and 2015 [3]. This increase in wasting and underweight indicates a worsening in nutritional deficiency among children under-five years in the country, and thus necessitating the conduct of this study.

The factors associated with wasting and underweight are complex ranging from community-, household-, environmental-, socioeconomic and cultural influences as well as child feeding practises and presence of infections. Three cross-sectional studies conducted on 208 hospitalised children in south west Nigeria [5], 366 preschool children in northern Nigeria [6] and 119 under-five aged children in north western Nigeria [7] identified factors such as presence of infections, non-exclusive breastfeeding and low maternal education, diarrhoeal episode, father’s education and family size (>6) as strong determinants of wasting and underweight. However, these small scale studies were limited in scope as data used were not nationally representative. Hence, findings from such studies could not be generalised to the entire Nigerian population. Addressing wasting and underweight at early stages of child’s growth is of critical importance due to the heightened risk of morbidity and mortality among children with suboptimal energy availability.

This study utilised data from the 2013 National Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) to determine the common predictors for wasting/severe wasting and underweight/severe underweight among Nigerian children aged 0–59 months and to describe the distribution of wasting and underweight by severity status across critical period of child growth. Thus, providing evidence on which interventions and policy actions can be formulated and implemented so Nigeria can achieve the World Health Assembly’s (WHA) Global Nutrition Target of reducing and maintaining childhood wasting to less than 5% and achieving a 30% reduction in low birth weight by 2025 [8].

2. Ethics

As this study was based on an analysis of existing survey datasets in the public domain that are freely available online with all identifier information removed, no ethics approvals were required. The first author obtained authorization for the download and usage of the NDHS dataset from MEASURE DHS/ICF International, Rockville, MD, USA.

3. Method

3.1. Data Sources

This study analysed data obtained from the 2013 NDHS. The survey was conducted by the National Population Commission (NPC) in collaboration with ICF Macro, Calverton, MD, USA [4].

In total, 40,680 households were selected for the survey with 39,902 women aged 15 to 49 years identified as eligible for individual interviews. Of which, 98% were successfully interviewed. A women’s questionnaire was used in recording the responses from all the women who participated in the survey.

In total, 30,050 children under the age of five were eligible for anthropometric measurements in all of the selected households. An overall 96% response rate was achieved with respect to height and weight measurements. Of the measurements carried out on the children, 88% were valid. This study focuses on the 24,529 children with valid and complete information on date of birth, height (cm) and weight (kg) [4].

Measurements were made using lightweight SECA scales (with digital screens) designed and manufactured under the authority of the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The measuring boards employed for the measurement of height were specially made for use in survey settings. For children under 2 years, recumbent length was recorded while standing height was measured for older children.

3.2. Dependent Variables

3.2.1. Wasting and Severe Wasting (Weight-for-Height)

The weight-for-height index measures body mass in relation to height and reflects current nutritional status. The index is calculated using growth standards published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2006. These growth standards were generated through data collected in the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study [9] and expressed in standard deviation units from the Multicentre Growth Reference Study median. Children with weight-for-height Z-scores below minus two standard deviations (−2 SD) from the median of the WHO reference population are considered wasted or acutely malnourished while children with Z-scores below minus three standard deviations (−3 SD) from the median of the WHO reference population are considered severely wasted.

3.2.2. Underweight and Severe Underweight (Weight-for-Age)

Weight-for-age is a composite index of height-for-age and weight-for-height. It takes into account both acute malnutrition (wasting) and chronic malnutrition (stunting), but it does not distinguish between the two. Children whose weight-for-age is below minus two standard deviations (−2 SD) from the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study median [9] are classified as underweight. Children whose weight-for-age is below minus three standard deviations (−3 SD) from the reference median are considered severely underweight.

3.3. Independent Variables

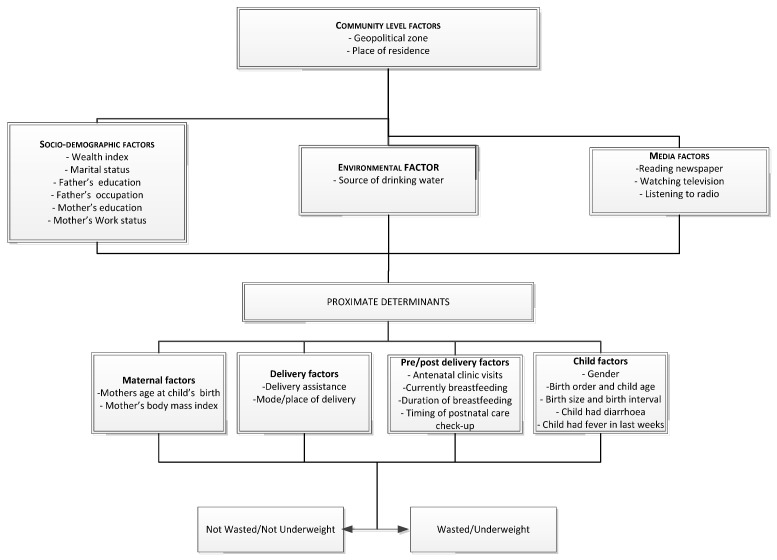

The potential risk factors were classified into five categories: Community level factors, socio-demographic factors, environmental factors, media factors and proximate determinants (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for analysing factors associated with wasting/underweight and severe wasting/severe underweight in under-five aged children in Nigeria.

Adopted from UNICEF Conceptual Framework (2013)

Community level factors included geopolitical zone and type of residence (urban or rural). Geopolitical zones were defined based on ethnic homogeneity among states with similar cultures, history and close territories as well as political, administrative and commercial cities in Nigeria. The socio-demographic, environmental and media factors are as represented in Figure 1. Household wealth index serves as an indicator consistent with expenditure and income measures. It was represented as a score of household assets via the principle components analysis method (PCA) [10]. Once this index was computed, scores were assigned to each de jure household member, ranking each person in the population by his or her score. The index was categorized into five national-level wealth quintiles: poorest, poor, middle, rich and richest. The bottom 40% of the households was referred to as the poorest and poor households, the next 20% as the middle-class households, and the top 40% as rich and richest households. Environmental factor was source of drinking water which was categorized into improved and unimproved according to WHO/UNICEF guidelines [11]. The proximate determinants were subdivided into maternal factors, delivery factors, pre/post-delivery factors and child factors (Figure 1). A combination of place of delivery and mode of delivery was further subdivided into three categories: home delivery, delivery at health facility with non-caesarean and delivery at health facility with caesarean.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

The indicator for wasting and underweight was expressed as a dependent dichotomous variable as follows:

Undernutrition; Category 0 (not wasted/not underweight (>−2 SD)) and category 1 (wasted/underweight (>−3 SD)).

Severe undernutrition; Category 0 (not severely wasted/not severely underweight (>−2 SD)) and category 1 (severely wasted/severely underweight (>−3 SD)).

These were examined against the set of independent variables in order to determine the factors associated with wasting/underweight and severe wasting/severe underweight in children under-five years.

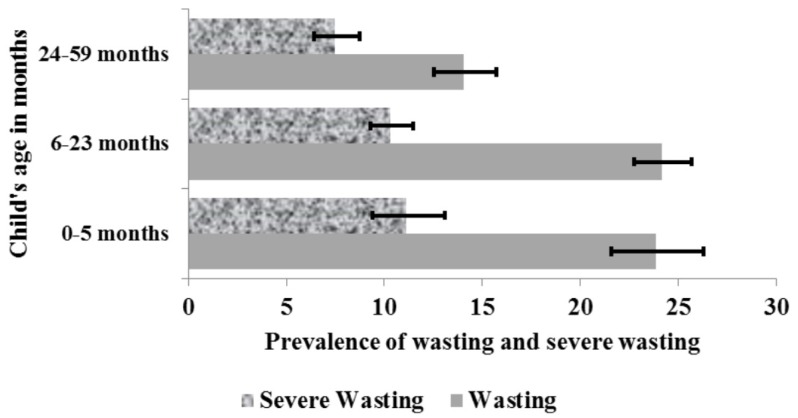

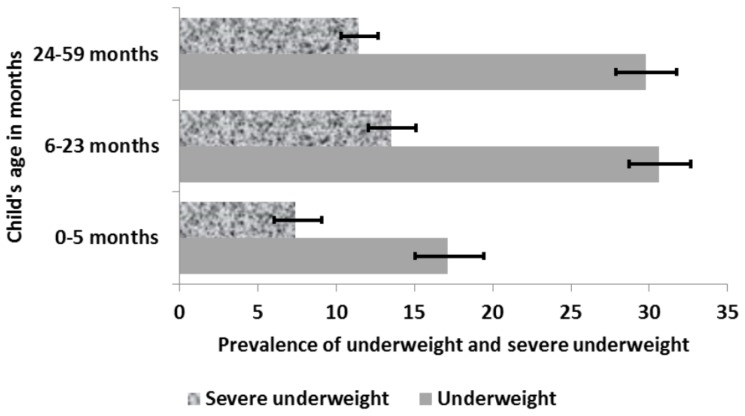

Analysis was performed using Stata version 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). The confidence intervals (CIs) around prevalence estimates of children aged 0–6 months, 6–23 months and 24–59 months was estimated using the Taylor series linearization method as reported in Figure 2 and Figure 3. These age groups were chosen because exclusive breastfeeding in the first six month of life, appropriate complementary feeding practices among children aged 6–23 months, and adequate psychosocial stimulation for children aged 24–59 months are important factors in reducing malnutrition.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of wasting and severe wasting by child’s age in months.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of underweight and severe underweight by child’s age in months.

Logistic regression generalized linear latent and mixed models (GLLAM) with the logit link and binomial family [12] that adjusted for cluster and survey weights were used to identify the factors associated with wasting/severe wasting and underweight/severe underweight amongst children aged 0–59 months.

Multivariable analysis was conducted using a five-stage conceptual modelling technique adopted from UNICEF [13] (Figure 1). The first stage involved entering community level factors into the baseline model to determine their association with the outcome variables. A stepwise backward elimination was performed and factors significantly associated with the study outcomes were retained. In the second modelling stage, socio-demographic factors were added to the significant factors from the first model and the backward elimination procedure was repeated. This protocol was followed for the inclusion of environmental factors, media factors and proximate determinants in the third, fourth, and fifth modelling stages respectively. In each stage, the factors with p-values < 0.05 were retained. To avoid any statistical bias, we confirmed our results by: (1) performing a backward elimination process on potential risk factors with a p-value < 0.20 obtained in the univariable analysis; (2) testing the backward elimination method by including all of the variables (all potential risk factors); and (3) testing and reporting collinearity. In order to determine the adjusted risk of the independent variables, the odds ratios with 95% CI were calculated and those with p < 0.05 were retained in the final model.

4. Results

The prevalence of wasting and severe wasting among children aged 0–59 months was 18% (95% CI: 17.1, 19.7) and 9% (95% CI: 7.9, 9.8), respectively. An analysis of the distribution of wasting by child’s age in months showed that children aged 0–23 months were more wasted and severely wasted than children aged 24–59 months (Figure 2).

Underweight and severe underweight among children aged 0–59 months was 29% (95% CI: 27.1, 30.5) and 12% (95% CI: 10.6, 12.9), respectively. Underweight and severe underweight was less predominant in children aged 0–5 months and highest among children aged 6–23 months as shown in Figure 3.

A total sample of 24,529 children aged 0–59 months was included in the study. Table 1 below shows the characteristics of the sample.

Table 1.

Characteristics of independent variables.

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Community Level Factors | ||

| Type of residence | ||

| Urban | 9067 | 37.0 |

| Rural | 15,465 | 63.0 |

| Geopolitical Zones | ||

| North Central | 3562 | 14.5 |

| North East | 4086 | 16.7 |

| North West | 8506 | 34.7 |

| South East | 2284 | 9.3 |

| South West | 2372 | 9.7 |

| South South | 3722 | 15.2 |

| Socio-demographic factors | ||

| Wealth Index | ||

| Poorest | 5378 | 21.9 |

| Poor | 5383 | 21.9 |

| Middle | 4711 | 19.2 |

| Rich | 4598 | 18.7 |

| Richest | 4462 | 18.2 |

| Mother’s working status | ||

| Non-working | 16,151 | 97.1 |

| Working (past 12 months) | 485 | 2.9 |

| Maternal education | ||

| No education | 11,378 | 46.4 |

| Primary | 4933 | 20.1 |

| Secondary and above | 8221 | 33.5 |

| Father’s occupation | ||

| Non agriculture | 20,237 | 82.5 |

| Agriculture | 1024 | 4.2 |

| Not working | 3271 | 13.3 |

| Father’s education | ||

| No education | 8870 | 37.0 |

| Primary | 4640 | 19.4 |

| Secondary and above | 10,447 | 43.6 |

| Marital status | ||

| Currently married | 23,592 | 97.6 |

| Formerly married (Divorce/Separated/Widow) | 579 | 2.4 |

| Mother’s literacy | ||

| Can’t read at all | 14,029 | 57.5 |

| Can read | 10,386 | 42.5 |

| Environmental factor | ||

| Source of drinking water | ||

| Protected | 13,878 | 56.6 |

| Unprotected | 10,653 | 43.4 |

| Media factors | ||

| Reading newspaper | ||

| Yes | 3589 | 14.7 |

| No | 20,793 | 85.3 |

| Listening to radio | ||

| Yes | 15,135 | 61.9 |

| No | 9314 | 38.1 |

| Watching TV | ||

| Yes | 11,690 | 47.9 |

| No | 12,732 | 52.1 |

| Proximate determinants | ||

| Maternal factors | ||

| Mother’s age | ||

| 15–24 years | 5780 | 23.6 |

| 25–34 years | 12,424 | 50.6 |

| 35–49 years | 6328 | 25.8 |

| Mother’s age at birth | ||

| <20 years | 3325 | 13.6 |

| 20–29 years | 12,878 | 52.5 |

| 30–39 years | 7161 | 29.2 |

| 40 and above | 1168 | 4.8 |

| Delivery factors | ||

| Type of delivery assistance | ||

| Health professional | 10,399 | 42.8 |

| Traditional birth attendant | 4938 | 20.3 |

| Relatives and other untrained personnel | 5856 | 24.1 |

| No one | 3113 | 12.8 |

| Place of delivery | ||

| Home | 15,065 | 61.4 |

| Health facility | 9467 | 38.6 |

| Mode of delivery | ||

| Non-caesarean | 23,734 | 97.8 |

| Caesarean | 523 | 2.2 |

| Combined Place and mode of delivery | ||

| Non-caesarean and Home delivery | 15,065 | 62.1 |

| Non-caesarean & Health facility | 8669 | 35.7 |

| Caesarean & Health facility | 523 | 2.2 |

| Pre/post-delivery factors | ||

| Antenatal clinic visits | ||

| None | 5177 | 32.8 |

| 1–3 | 1954 | 12.4 |

| 4+ | 8674 | 54.9 |

| Timing of postnatal check-up | ||

| No postnatal check-up | 19,243 | 78.4 |

| 0–2 days | 3748 | 15.3 |

| Delayed | 1541 | 6.3 |

| Currently breastfeeding | ||

| Yes | 13,950 | 56.9 |

| No | 10,582 | 43.1 |

| Duration of breastfeeding | ||

| up to 12 months | 5376 | 22.3 |

| >12 months | 18,792 | 77.8 |

| Child factors | ||

| Birth order | ||

| First-born | 4641 | 19.0 |

| 2nd–4th | 11,327 | 46.2 |

| 5 or more | 8564 | 34.9 |

| Preceding birth interval | ||

| No previous birth | 4641 | 19.0 |

| <24 months | 4326 | 17.7 |

| >24 months | 15,520 | 63.4 |

| Sex of child | ||

| Male | 12,193 | 49.7 |

| Female | 12,339 | 50.3 |

| Perceived birth size | ||

| Small | 3385 | 14.0 |

| Average | 10,052 | 41.5 |

| Large | 10,759 | 44.5 |

| Child’s age in months | ||

| 0–5 | 2238 | 9.3 |

| 6–23 | 7876 | 32.8 |

| 24–59 | 13,915 | 57.9 |

| Child had diarrhoea recently | ||

| No | 21,885 | 89.3 |

| Yes | 2556 | 10.4 |

| Child had fever in last two weeks | ||

| No | 21,251 | 86.6 |

| Yes | 3153 | 12.9 |

5. Multivariate Analysis

Table 2 summarises the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (OR) for the association between the independent variables and wasting (moderate and severe), while Table 3 shows the corresponding OR for underweight and severe underweight, respectively.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (OR) (95% CI) for wasted and severely wasted children aged 0–59 months.

| Characteristics | Wasted Children 0–59 Months | Severely Wasted Children 0–59 Months | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Odd Ratio (95% CI) | p | Adjusted Odd Ratio (95% CI) | p | Unadjusted Odd Ratio (95% CI) | p | Adjusted Odd Ratio (95% CI) | p | |

| Community Level Factors | ||||||||

| Type of residence | ||||||||

| Urban | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Rural | 1.05 (0.86, 1.28) | 0.641 | 0.72 (0.59, 0.89) | 0.001 | 1.07 (0.81, 1.41) | 0.641 | 0.71 (0.55, 0.93) | 0.013 |

| Geopolitical Zones | ||||||||

| North Central | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| North East | 1.73 (1.38, 2.17) | <0.001 | 1.51 (1.19, 1.91) | 0.001 | 2.07 (1.46, 2.94) | <0.001 | 1.87 (1.31, 2.66) | 0.001 |

| North West | 2.59 (2.09, 3.22) | <0.001 | 2.42 (1.93, 3.03) | <0.001 | 3.60 (2.62, 4.95) | <0.001 | 3.17 (2.28, 4.40) | <0.001 |

| South East | 0.98 (0.77, 1.23) | 0.837 | 0.81 (0.63, 1.05) | 0.112 | 0.91 (0.63, 1.32) | 0.613 | 0.69 (0.47, 1.04) | 0.074 |

| South West | 0.92 (0.72, 1.16) | 0.473 | 0.88 (0.69, 1.12) | 0.285 | 0.82 (0.56, 1.21) | 0.316 | 0.75 (0.51, 1.10) | 0.143 |

| South South | 0.78 (0.62, 0.98) | 0.031 | 0.67 (0.52, 0.85) | 0.001 | 0.61 (0.42, 0.87) | 0.007 | 0.49 (0.33, 0.71) | <0.001 |

| Socio-demographic factors | ||||||||

| Mother’s education | ||||||||

| No education | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Primary | 0.65 (0.57, 0.74) | <0.001 | 0.90 (0.78, 1.04) | 0.160 | 0.53 (0.44, 0.63) | <0.001 | 0.81 (0.66, 0.98) | 0.002 |

| Secondary and above | 0.54 (0.47, 0.62) | <0.001 | 0.79 (0.67, 0.94) | 0.007 | 0.47 (0.38, 0.58) | <0.001 | 0.74 (0.58, 0.94) | 0.014 |

| Father’s education | ||||||||

| No education | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Primary | 0.67 (0.58, 0.76) | <0.001 | 0.89 (0.77, 1.03) | 0.120 | 0.57 (0.47, 0.70) | <0.001 | 0.84 (0.68, 1.03) | 0.095 |

| Secondary and above | 0.57 (0.50, 0.65) | <0.001 | 0.77 (0.67, 0.88) | <0.001 | 0.47 (0.39, 0.58) | <0.001 | 0.65 (0.53, 0.79) | <0.001 |

| Watching TV | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| No | 1.28 (1.13, 1.46) | <0.001 | 0.78 (0.68, 0.88) | <0.001 | 1.30 (1.08, 1.57) | 0.005 | 0.68 (0.56, 0.82) | <0.001 |

| Proximate determinants | ||||||||

| Maternal factors | ||||||||

| Mother’s BMI | ||||||||

| <18.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| 18.5–25 | 0.66 (0.56, 0.78) | <0.001 | 0.76 (0.64, 0.90) | 0.002 | 0.73 (0.59, 0.91) | 0.005 | ||

| 25+ | 0.48 (0.39, 0.59) | <0.001 | 0.68 (0.56, 0.83) | <0.001 | 0.56 (0.43, 0.74) | <0.001 | ||

| Delivery factors | ||||||||

| Type of delivery assistance | ||||||||

| No one | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Traditional birth attendant | 1.85 (1.59, 2.15) | <0.001 | 1.39 (1.11, 1.73) | 0.004 | 2.25 (1.79, 2.82) | <0.001 | ||

| Relatives or other | 1.77 (1.53, 2.05) | <0.001 | 1.44 (1.14, 1.80) | 0.002 | 2.08 (1.74, 2.49) | <0.001 | ||

| Health professional | 1.84 (1.55, 2.19) | <0.001 | 1.11 (0.88, 1.41) | 0.367 | 2.39 (1.88, 3.04) | <0.001 | ||

| Combined Place/mode of delivery | ||||||||

| Home delivery | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Health facility with non-caesarean | 0.59 (0.52, 0.67) | <0.001 | 1.12 (0.92, 1.37) | 0.254 | 0.47 (0.39, 0.57) | <0.001 | 0.79 (0.65, 0.96) | 0.017 |

| Health facility with caesarean | 0.31 (0.20, 0.46) | <0.001 | 0.61 (0.39, 0.94) | 0.025 | 0.24 (0.14, 0.43) | <0.001 | 0.44 (0.24, 0.79) | 0.007 |

| Child factors | ||||||||

| Sex of child | ||||||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Female | 0.88 (0.81, 0.95) | 0.001 | 0.83 (0.77, 0.89) | <0.001 | 0.85 (0.76, 0.94) | 0.002 | 0.79 (0.71, 0.88) | <0.001 |

| Perceived birth size | ||||||||

| Small | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Average | 0.76 (0.66, 0.87) | <0.001 | 0.85 (0.74, 0.97) | 0.017 | 0.72 (0.60, 0.85) | <0.001 | 0.81 (0.68, 0.96) | 0.018 |

| Large | 0.60 (0.52, 0.69) | <0.001 | 0.66 (0.57, 0.76) | <0.001 | 0.57 (0.48, 0.67) | <0.001 | 0.64 (0.53, 0.77) | <0.001 |

| Child had fever in last two weeks | ||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Yes | 1.07 (0.94, 1.21) | 0.312 | 1.18 (1.06, 1.32) | 0.003 | 0.81 (0.68, 0.98) | 0.028 | ||

| Child’s age in months | 0.98 (0.98, 0.98) | <0.001 | 0.98 (0.98, 0.98) | <0.001 | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | <0.001 | 0.98 (0.98, 0.99) | <0.001 |

Independent variables adjusted for are: Type of residence, geopolitical zones, wealth index, mother’s working status, maternal education, fathers occupation, father’s education, marital status, mother’s literacy, source of drinking water, reading newspaper, listening to radio, watching TV, mother’s age, mother’s age at birth, type of delivery assistance, combined place and mode of delivery, antenatal clinic visits, timing of postnatal check-up, currently breastfeeding, duration of breastfeeding, birth order, preceding birth interval, sex of child, perceived birth size, child’s age in months, child had diarrhoea recently, child had fever in last two weeks.

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (OR) (95% CI) for underweight and severely underweight children aged 0–59 months.

| Characteristics | Underweight Children 0–59 Months | Severely Underweight Children 0–59 Months | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Odd Ratio (OR) (95% CI) | p | Adjusted Odd Ratio (AOR) (95% CI) | p | Unadjusted Odd Ratio (OR) (95% CI) | p | Adjusted Odd Ratio (AOR) (95% CI) | p | |

| Community Level Factors | ||||||||

| Geopolitical Zones | ||||||||

| North Central | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| North East | 1.97 (1.58, 2.45) | <0.001 | 1.44 (1.17, 1.78) | 0.001 | 1.85 (1.34, 2.56) | <0.001 | 1.48 (1.06, 2.06) | 0.021 |

| North West | 3.94 (3.20, 4.84) | <0.001 | 3.22 (2.58, 4.01) | <0.001 | 4.37 (3.19, 5.98) | <0.001 | 3.82 (2.72, 5.35) | <0.001 |

| South East | 0.52 (0.39, 0.67) | <0.001 | 0.47 (0.36, 0.59) | <0.001 | 0.38 (0.24, 0.58) | <0.001 | 0.32 (0.21, 0.49) | <0.001 |

| South West | 0.64 (0.51, 0.81) | <0.001 | 0.64 (0.51, 0.79) | <0.001 | 0.49 (0.32, 0.75) | 0.001 | 0.48 (0.32, 0.73) | 0.001 |

| South South | 0.73 (0.58, 0.93) | 0.011 | 0.76 (0.60, 0.96) | 0.022 | 0.53 (0.35, 0.80) | 0.003 | 0.52 (0.34, 0.78) | 0.002 |

| Socio-demographic factors | ||||||||

| Mother’s education | ||||||||

| No education | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Primary | 0.48 (0.43, 0.54) | <0.001 | 0.89 (0.79, 1.01) | 0.062 | 0.49 (0.41, 0.58) | <0.001 | ||

| Secondary and higher | 0.29 (0.26, 0.35) | <0.001 | 0.74 (0.62, 0.87) | <0.001 | 0.28 (0.21, 0.36) | <0.001 | ||

| Father’s education | ||||||||

| No Education | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Primary | 0.56 (0.49, 0.63) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.85, 1.08) | 0.500 | 0.62 (0.52, 0.74) | <0.001 | 1.14 (0.95, 1.36) | 0.153 |

| Secondary and higher | 0.38 (0.33, 0.43) | <0.001 | 0.78 (0.69, 0.88) | <0.001 | 0.38 (0.31, 0.46) | <0.001 | 0.85 (0.71, 1.03) | 0.103 |

| Proximate determinants | ||||||||

| Maternal factors | ||||||||

| Mother’s BMI | ||||||||

| <18.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 18.5–25 | 0.56 (0.48, 0.66) | <0.001 | 0.67 (0.57, 0.78) | <0.001 | 0.64 (0.53, 0.78) | <0.001 | 0.78 (0.63, 0.95) | 0.015 |

| 25+ | 0.30 (0.25, 0.37) | <0.001 | 0.52 (0.43, 0.63) | <0.001 | 0.35 (0.28, 0.46) | <0.001 | 0.66 (0.51, 0.84) | 0.001 |

| Delivery factors | ||||||||

| Combined Place/mode of delivery | ||||||||

| Home delivery | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Health facility with non-caesarean | 0.38 (0.33, 0.43) | <0.001 | 0.85 (0.76, 0.95) | <0.001 | 0.34 (0.28, 0.41) | <0.001 | 0.69 (0.52, 0.91) | 0.008 |

| Health facility with caesarean | 0.26 (0.18, 0.37) | <0.001 | 0.69 (0.48, 0.99) | 0.016 | 0.27 (0.16, 0.47) | <0.001 | 0.67 (0.33, 1.36) | 0.268 |

| Currently breastfeeding | ||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Yes | 0.85 (0.79, 0.92) | <0.001 | 0.89 (0.81, 0.97) | 0.007 | 0.84 (0.75, 0.95) | 0.005 | ||

| Duration of breastfeeding | ||||||||

| up to 12 months | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| >12 months | 1.36 (1.24, 1.49) | <0.001 | 1.61 (1.44, 1.80) | <0.001 | 1.22 (1.07, 1.38) | 0.002 | 1.91 (1.64, 2.23) | <0.001 |

| Child factors | ||||||||

| Preceding birth interval | ||||||||

| No previous birth | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| <24 months | 1.32 (1.18, 1.48) | <0.001 | 1.11 (0.98, 1.26) | 0.093 | 1.48 (1.23, 1.77) | <0.001 | 1.29 (1.06, 1.56) | 0.010 |

| >24 months | 1.16 (1.05, 1.27) | 0.002 | 0.97 (0.88, 1.07) | 0.513 | 1.25 (1.09, 1.44) | 0.002 | 1.04 (0.89, 1.19) | 0.620 |

| Sex of child | ||||||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Female | 0.86 (0.80, 0.92) | <0.001 | 0.79 (0.74, 0.85) | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.78, 0.95) | 0.002 | 0.79 (0.72, 0.88) | <0.001 |

| Perceived birth size | ||||||||

| Small | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Average | 0.72 (0.64, 0.82) | <0.001 | 0.87 (0.76, 0.99) | 0.044 | 0.66 (0.56, 0.77) | <0.001 | 0.78 (0.65, 0.93) | 0.005 |

| Large | 0.49 (0.43, 0.55) | <0.001 | 0.55 (0.48, 0.63) | <0.001 | 0.44 (0.37, 0.52) | <0.001 | 0.50 (0.41, 0.60) | <0.001 |

| Child had diarrhoea recently | ||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Yes | 1.51 (1.35, 1.69) | <0.001 | 1.36 (1.21, 1.53) | <0.001 | 1.55 (1.34, 1.78) | <0.001 | 1.43 (1.24, 1.65) | <0.001 |

| Child had fever in last two weeks | ||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Yes | 1.28 (1.15, 1.43) | <0.001 | 1.35 (1.21, 1.51) | <0.001 | 1.13 (0.96, 1.32) | 0.137 | 1.22 (1.03, 1.46) | 0.024 |

| Child’s age in months | 1.00 (1.00, 1.01) | 0.002 | 0.99 (0.99, 0.99) | 0.002 | 0.98 (0.98, 0.99) | <0.001 | ||

Independent variables adjusted for are: Type of residence, geopolitical zones, wealth index, mother’s working status, maternal education, fathers occupation, father’s education, marital status, mother’s literacy, source of drinking water, reading newspaper, listening to radio, watching TV, mother’s age, mother’s age at birth, type of delivery assistance, combined place and mode of delivery, antenatal clinic visits, timing of postnatal check-up, currently breastfeeding, duration of breastfeeding, birth order, preceding birth interval, sex of child, perceived birth size, child’s age in months, child had diarrhoea recently, child had fever in last two weeks.

5.1. Factors Associated with Wasting and Severe Wasting

Children residing in rural areas and in the North West geopolitical zone were significantly more predisposed to wasting and severe wasting than those in urban areas and other geopolitical zones. Children of uneducated parents and living in households that do not watch television had significantly higher odds of being wasted and severely wasted compared with those of educated parent and exposed to the media. Children who were delivered at home and children who were perceived to be small by their mothers at birth were more likely to be wasted and severely wasted than those delivered at a health facility and perceived to have been large. Male children and mothers with BMI less than 18.5 kg/m2 were significantly more susceptible to wasting and severe wasting than their female counterparts and mothers with BMI greater than 18.5 kg/m2. Children who were delivered with no assistance from health professionals and children who had fever in the two weeks preceding the survey were more likely to be wasted compared with children who had assisted delivery and who did not have fever. Child’s age was also significantly associated with wasting and severe wasting.

5.2. Factors Associated with Underweight and Severe Underweight

Children residing in the North West geopolitical zone, and born to uneducated parents were significantly more likely to be underweight and severely underweight compared with those who were born to educated parents and reside in other geopolitical zones. Children who were delivered at home, and whose mothers had BMI less than 18.5 kg/m2 were significantly more likely to be underweight and severely underweight compared with those delivered at a health facility and whose mothers had BMI greater than 18.5 kg/m2. Children who had a prolonged period of breastfeeding (>12 months), and children whose mothers reported a preceding birth interval of less than 24 months were more likely to be underweight and severely underweight compared with those who were breastfed for less than 12 months and had more than 24 months birth interval. Male children were more likely to be underweight and severely underweight compared with their female counterparts. Children who were perceived by their mothers to have been small at birth, and children who were not being breastfed were more likely to be underweight and severely underweight than those that were perceived to have been large and were being breastfed. Children who had diarrhoea and fever in the two weeks prior to the survey were significantly more likely to be underweight and severely underweight compared with those who had neither diarrhoea nor fever. Child’s age was significantly associated with severe underweight.

6. Discussion

Our analysis reported that children aged 0–5 months and 6–23 months are the most affected by wasting and severe wasting (Figure 2) while children aged 6–23 months and 24–59 months are the most affected by underweight and severe underweight (Figure 3). Inadequate nutrition in the first two years of life leads to acute weight loss and prevents the child from developing at a rate where its body weight is commensurate to its height. The mother’s nutritional status is very important to the proper development of the child in utero and continues to be for at least the first six months of post-natal life when the child is totally dependent on the mother for all its nutrient supply. Failure of the mother to exclusively breastfeed the child in the first six months may lead to growth deficit [14]. After six months, a child requires adequate complementary foods for optimal growth [15,16]. The period of transition from exclusively breastfeeding (0–6 months) to the introduction of complementary foods (6–23 months) is a very critical period where the child is most vulnerable to malnutrition. Prolonged breastfeeding without the timely introduction of supplementary foods that is of good quality, quantity and at the right frequency to cater for the nutritional needs of the growing child while maintaining breastfeeding may result in undernutrition and frequent illness [17]. This finding is consistent with WHO recommendation that infants should start receiving adequate complementary foods at 6 months of age in addition to breast milk to avoid being malnourished [17]. Furthermore, children aged 24–59 months require more energy (calories) and nutrients for proper growth and development. As the child grows, its energy needs increases and so should its energy (calories) intake in order to maintain the appropriate weight for its age. It is therefore crucial they obtain their daily energy from a varied, healthy and balanced diet. Inability to meet the growing energy and nutrient needs of the child results in the child being underweight.

In this study, children who resided in the North East, North West and North Central geopolitical zones of Nigeria had a significantly higher risk of being wasted and underweight. This could either be due to political unrest in the region or the neglect of agriculture as well as the effect of cultural preferences on food choice where certain types of food are not given to children even though the food are nutritious, but instead the children are fed a monotonous rice-based native meal with low nutrient all year round [18]. This has led to the recent concerns of the Nigerian government with the level of malnutrition in the Northern region of the country [19]. A similar cross-sectional study carried out in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) revealed that malnutrition rates remain very high in provinces that rely on the mining industry (Katanga, the two Kasai and the Orientale) as the younger generation has left the agricultural sector to work in the mining industries. These rates where comparable to the level seen in the Eastern provinces under war as people do not cultivate due to the violence [20].

The mother’s perception of the birth size of their child was significantly associated with the child’s nutritional status. Children who were perceived to be small at birth were more susceptible to wasting as well as being underweight compared with those perceived to be large; this is consistent with results of previous studies in Ethiopia [21], Brazil [22] and Pakistan [23] that reported birth size as a valid indicator of subsequent growth. However, caution should be taken in interpreting this result, as the rationale used by the mothers in estimating the size of their babies is unclear. Reduced birth size maybe a result of poor maternal nutrition during pregnancy when the child is totally dependent on the mother for its nutrition in utero via the placenta, thus any nutrition deprivation from the mother will affect the growth and proper development of the foetus [4]. This finding thus highlights the importance of women’s health and prenatal care for giving their offspring a better chance in life.

In this study, male children had a significantly higher risk of being wasted and underweight than their female counterparts. Male children tend to engage in higher intensity physical activity thereby using up large amounts of energy that was meant for proper growth and development. Meanwhile, female children are culturally expected to perform lower intensity physical activity which includes staying at home with their mothers near food preparation thereby conserving and channelling more energy to growth and development. This finding is consistent with results from other cross-sectional studies carried out in Ethiopia [21] and South Africa [24] which also found that males’ were more likely to be undersized and underweight than females. However, a biological reason for this is still unknown.

In this study, place of delivery significantly increased a child’s vulnerability to wasting and underweight. Children delivered at home tend to have poorer nutritional status than children delivered at a health facility. Studies have shown a strong association between institutional delivery and mother’s education, which in turn affects child health [25,26]. Home delivery is mostly practised by women of lower educational status [26]; these women tend to lack the necessary knowledge needed to make informed decisions concerning the health of their child. Women who deliver at home also miss out on the valuable post-natal counselling provided at the health facilities, which may help in improving the nutritional status of both mother and child.

This study also revealed that children who suffered a contraction of fever or diarrhoea in the two weeks preceding the survey tend to be more nutritionally deprived than children who did not. The occurrence of fever or diarrhoea and malnutrition are interrelated; fever and diarrhoea tend to reduce appetite and interfere with the digestion and absorption of food consumed which in turn exacerbates malnutrition thus directing essential nutrients away from growth towards immune response thereby leading to growth failure [27]. In a recent cross-sectional study conducted in Ethiopia, it was discovered that the children who had fever two weeks prior to the survey showed poorer nutritional status [21]. Another study conducted in South Ethiopia reported that the presence of diarrhoea in under-five year old children two weeks prior to the survey was significantly associated with malnutrition [28].

Children whose mothers had a BMI less than 18.5 kg/m2 were significantly more likely to be wasted and underweight than those whose mothers had a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or higher. Mother’s BMI is an important determinant of malnutrition in children, therefore supplementary food for the mothers in the prenatal and postnatal period is recommended in order to improve child growth. A similar cross-sectional study conducted in Ethiopia reported that the mother’s BMI, which is an indicator of the mother’s nutritional status, was significantly associated with wasting in their offspring [21].

In this study, children whose parents resided in rural areas were more undernourished than those residing in the urban areas. Health facilities in rural areas are often ill-equipped for delivering the required primary health care services [20]. Rural areas also lack access to safe water supply, proper housing and adequate sanitation, which are preconditions for adequate nutrition and directly affect health. This inequality results in a greater susceptibility to infections and slow recovery from illness thereby adversely affecting growth. This finding is consistent with results from a cross-sectional study carried out in the DRC, which also found that the rate of malnutrition was significantly higher in rural areas compared to urban areas [20].

Children born to uneducated parents tend to be at a higher risk of malnutrition than children born to educated parents. This result supports the potential link of maternal education to child health. A higher maternal education translates into greater health care utilization, including formal prenatal and postnatal visits. It exposes mothers to a better understanding of diseases and adoption of modern medical practices. Higher maternal education leads to greater female autonomy, which in turn influences health-related decisions and the allocation of resources for food within the household [26]. Education on the nutritional value of foods and the best way of food preparation add to improving the nutritional status of the child. In a cross-sectional study conducted in Kenya, higher maternal education was reported to be associated with maternal employment and higher household income [29], which in turn improves the child’s access to good quality food. Similarly, father’s education also translates to a higher household income and food security. Previous cross-sectional studies conducted in Zambia [30], Iran [31] and Nepal [32] on the relationship between wealth index and malnutrition reported that children from poor households were more likely to be undernourished than those from rich households. This may be attributed to the fact that with less income to spend on proper nutrition, children from underprivileged households are more susceptible to growth failure due to insufficient food intake.

Children from households exposed to the media (television) are less prone to wasting and severe wasting as their parents are socially more advanced and tend to be more exposed to important information about proper nutrition and child feeding practices. This finding is similar to that of a cross-sectional study conducted in Bangladesh which highlighted a positive relationship between the media and wasting [33].

Our study had several strengths. Firstly, the study was population-based with a large sample size that yielded a 96% and 98% response rate for children and women respectively. Secondly, the study used the 2013 NDHS dataset, which is the most recent nationally recognised data available in Nigeria thereby giving relevance to the study. Thirdly, appropriate statistical adjustments were applied to the 2013 NDHS dataset and the most vulnerable subpopulation affected by wasting/severe wasting or underweight/severe underweight was identified. However, the study was limited in a number of ways. Firstly, we were unable to establish a causal relationship between the observed risk factors and the dependent variables due to the cross-sectional nature of the study design. Secondly, despite the use of a comprehensive set of variables in our analysis, the effect of residual confounding as a result of unmeasured co-variates could not be ruled out; this include direct measures of child’s diet and feeding pattern as well as energy expenditure through physical activity to identify possible casual paths.

Policy Implications

Intervention strategies geared towards improving mother’s knowledge about exclusive breastfeeding and adequate complimentary feeding practices should be implemented and should target mothers from poor socio-economic group. The Nigerian government should also focus on provision of accessible health care services to all mothers especially those from the northern geopolitical region of the country.

Findings from this study will enable policy makers and public health researchers to develop effective nutrition interventions targeting the most vulnerable subpopulation that could be translated into policy actions to reduce the double burden of malnutrition in Nigeria.

7. Conclusions

Considering the findings in this study, it is critical that community-based interventions need to be formulated and implemented in order to improve child health. At the individual level, interventions should focus on educating mothers on the basics of proper nutrition and the need to utilize available health services. At the community level, healthcare systems that facilitate public health interventions such as maternal-and-child health programs need to be made accessible to women in rural areas. These interventions will improve the nutritional status of children under-five years in Nigeria, thereby setting the country on the path to achieving the WHO global nutrition target by 2025.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of the first author’s thesis for a doctoral dissertation with the School of Science and Health at the Western Sydney University, Australia. We are grateful to Measure DHS, ORC Macro, Calverton, MD, USA for providing the 2013 NDHS data for this analysis. No grant was received for this study from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contributions

This study was designed by B.J.A. and K.E.A. B.J.A. carried out the analysis and drafted the manuscript. K.E.A., D.M., A.M.R. and J.J.H. were involved in the revision and editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Guideline: Updates on the Management of Severe Acute Malnutrition in Infants and CHILDREN. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The United Nations Children’s Fund. World Health Organization. World Bank . UNICEF, WHO—The World Bank Child Malnutrition Database: Estimates for 2015 and Launch of Interactive Data Dashboards. The United Nations Children’s Fund; New York, NY, USA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Population Commission (NPC) ICF International . Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2013. National Population Commission; Abuja, Nigeria: ICF International; Rockville, MD, USA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogunlesi T.A., Ayeni V.A., Fetuga B.M., Adekanmbi A.F. Severe acute malnutrition in a population of hospitalized under-five Nigerian children. Niger. Postgrad. Med. J. 2015;22:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balogun T.B., Yakubu A.M. Recent illness, feeding practices and father’s education as determinants of nutritional status among preschool children in a rural Nigerian community. J. Trop. Paediatr. 2015;61:92–99. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmu070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Idris S.H., Popoola-Zakariyya B., Sambo M.N., Sufyan M.B., Abubakar A. Nutritional status and pattern of infant feeding practices among children under-five in a rural community of north-western Nigeria. Int. Q. Community Health Educ. 2013;33:83–94. doi: 10.2190/IQ.33.1.g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization Maternal, Infant and Young Child Nutrition: Draft Comprehensive Implementation Plan; Proceedings of the Sixth-Fifth World Health Assembly; Geneva, Switzerland. 21–26 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Onis M. WHO Child Growth Standards: Length/Height-for-Age, Weight-for-Age, Weight-for-Length, Weight-for-Height and Body Mass Index-for-Age. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Filmer D., Pritchett L.H. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure Data—Or tears: An application to educational enrolments in states of India. Demography. 2001;38:115–132. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization . Progress on Drinking-Water and Sanitation. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: Mar 6, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rabe-Hesketh S., Skrondal A. Multilevel modelling of complex survey data. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A. 2006;169:805–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2006.00426.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.United Nations Children’s Fund . Improving Child Nutrition: The Achievable Imperative for Global Progress. United Nations Children’s Fund; New York, NY, USA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agho K.E., Dibley M.J., Odiase J.I., Ogbonmwan S.M. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-11-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogbo F.A., Page A., Idoko J., Claudio F., Agho K.E. Trends in complementary feeding indicators in Nigeria, 2003–2013. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008467. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Issaka A.I., Agho K.E., Page A.N., Burns P.L., Stevens G.J., Dibley M.J. Determinants of suboptimal complementary feeding practices among children aged 6–23 months in four anglophone West African countries. Matern. Child Nutr. 2015;11(Suppl. 1):14–30. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization . Complementary Feeding of Young Children in Developing Countries: A Review of Current Scientific Knowledge. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1998. p. 230. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mwangome M., Prentice A., Plugge E., Nweneka C. Determinants of appropriate child health and nutrition practices among women in rural Gambia. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2010;28:167–172. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v28i2.4887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barker T., Pittore K. Report of the WINNN-ORIE Nutrition Stakeholders Engagement Event, 29 April 2014, Abuja. Operational Research and Impact Evaluation; Northern Region, Nigeria: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kandala N.B., Madungu T.P., Emina J.B., Nzita K.P., Cappuccio F.P. Malnutrition among children under the age of five in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC): Does geographic location matter? BMC Public Health. 2011;11:261. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dabale G.A., Sharma M.K. Determinants of Wasting Among Under-Five Children in Ethiopia: (A Multilevel Logistic Regression Model Approach) Int. J. Stat. Med. Res. 2014;3:368. doi: 10.6000/1929-6029.2014.03.04.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vitolo M.R., Gama C.M., Bortolini G.A., Campagnolo P.D., Drachler M.D.L. Some risk factors associated with overweight, stunting and wasting among children under 5 years old. J. Pediatr. 2008;84:251–257. doi: 10.2223/JPED.1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasnain S.F., Hashmi S.K. Consanguinity among the risk factors for underweight in children under five: A study from Rural Sindh. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad. 2009;21:111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lesiapeto M.S., Smuts C.M., Hanekom S.M., Du Plessis J., Faber M. Risk factors of poor anthropometric status in children under five years of age living in rural districts of the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal provinces, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010;23:202–207. doi: 10.1080/16070658.2010.11734339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shrestha S.K., Banu B., Khanom K., Ali L., Thapa N., Stray-Pedersen B., Devkota B. Changing trends on the place of delivery: Why do Nepali women give birth at home? Reprod. Health. 2012;9:25. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-9-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsumura M., Gubhaju B. Women’s Status, Household Structure and the Utilization of Maternal Health Services in Nepal: Even primary-leve1 education can significantly increase the chances of a woman using maternal health care from a modem health facility. Asia-Pac. Popul. J. 2001;16:23–44. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Black R.E., Victora C.G., Walker S.P., Bhutta Z.A., Christian P., de Onis M., Uauy R. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2013;382:427–451. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asfaw M., Wondaferash M., Taha M., Dube L. Prevalence of undernutrition and associated factors among children aged between six to fifty nine months in Bule Hora district, South Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:41. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1370-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masibo P.K., Makoka D. Trends and determinants of undernutrition among young Kenyan children: Kenya Demographic and Health Survey; 1993, 1998, 2003 and 2008–2009. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15:1715–1727. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012002856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masiye F., Chama C., Chitah B., Jonsson D. Determinants of child nutritional status in Zambia: An analysis of a national survey. Zamb. Soc. Sci. J. 2010;1:4. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kavosi E., Hassanzadeh Rostami Z., Kavosi Z., Nasihatkon A., Moghadami M., Heidari M. Prevalence and determinants of under-nutrition among children under six: A cross-sectional survey in Fars province, Iran. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2014;3:71–76. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tiwari R., Ausman L.M., Agho K.E. Determinants of stunting and severe stunting among under-fives: Evidence from the 2011 Nepal Demographic and Health Survey. BMC Paediatr. 2014;14:239. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rahman A., Chowdhury S., Hossain D. Acute malnutrition in Bangladeshi children: Levels and determinants. Asia-Pac. J. Public Health. 2009;21:294–302. doi: 10.1177/1010539509335399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]