Abstract

Objectives

Annually, millions of people in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) receive HIV counselling and testing (HCT), a service designed to inform persons of their HIV status and, if HIV-uninfected, reduce HIV acquisition risk. However, the impact of HCT on HIV acquisition has not been systematically evaluated. We conducted a systematic review to assess this relationship in SSA.

Methods

We searched for articles from sub-Saharan Africa meeting the following criteria: an HIV-uninfected population, HCT as an exposure, longitudinal design, and an HIV acquisition endpoint. Three sets of comparisons were assessed and divided into strata: A) sites receiving HCT versus sites not receiving HCT, B) persons receiving HCT versus persons not receiving HCT, and C) persons receiving couple HCT versus persons receiving individual HCT.

Results

We reviewed 1635 abstracts; eight met all inclusion criteria. Strata A consisted of one cluster randomised trial with a non-significant trend towards HCT being harmful: incidence rate ratio (IRR): 1.4. Strata B consisted of five observational studies with non-significant unadjusted IRRs from 0.6 to 1.5. Strata C consisted of two studies. Both displayed trends towards couple HCT being more protective than individual HCT (IRRs: 0.3 to 0.5). All studies had at least one design limitation.

Conclusions

In spite of intensive scale-up of HCT in SSA, few well-designed studies have assessed the prevention impacts of HCT. The limited body of evidence suggests that individual HCT does not have a consistent impact on HIV acquisition, and couple HCT is more protective than individual HCT.

Keywords: HIV, systematic review, sub-Saharan Africa, research design, counselling, incidence

Introduction

In sub-Saharan Africa, the HIV response has intensified dramatically since 2003, when the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) was introduced. HIV counselling and testing (HCT), a gateway for HIV treatment, has been brought to scale with tens of millions of annual tests [1–4]. Individual and couple HCT are essential for linking HIV-infected persons to HIV treatment, which reduces morbidity, mortality, and horizontal and vertical transmissibility [5, 6]. Similarly, individual and couple HCT can now serve as referral points for HIV-uninfected men to access medical male circumcision, and, in the near future, may serve as an entry-point for antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis [7–9]. However, historically, individual and couple HCT relied strictly on behavioural HIV prevention messages. The relationship between individual and couple HCT and HIV acquisition is not well understood, in spite of three decades of implementation. Given the high volume of HCT, the high proportion of negative test results, and the slow scale-up of biomedical prevention, understanding the impact of individual and couple HCT on HIV acquisition is essential for guiding the magnitude and nature of future HCT rollout, as well as the relative emphasis of individual and couple HCT.

HCT typically consists of three components: pre-test counselling, HIV testing, and post-test counselling [10]. Typically, in pre-test counselling, HIV natural history and modes of transmission are explained, as well as behavioural HIV prevention measures. In individual pre-test-counselling, the counselling is tailored to the client’s personal risk factors. Currently, HIV testing is conducted with rapid tests with real-time results, but historically HIV testing was laboratory-based, with results becoming available days or weeks later. Post-test counselling typically involves return of results with differentiated messages for HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected clients. For HIV-infected clients, the discussion is focused on care and treatment, psychosocial support, and methods for preventing onward HIV transmission. For HIV-uninfected clients, messages address HIV acquisition through partner reduction, condom use, and faithfulness to one partner.

Couple HCT is an approach in which two members of a couple undergo HCT together, enabling both persons to learn their own status and their partner’s HIV status simultaneously. Couple HCT allows for a couple diagnosis: both persons HIV-uninfected (HIV concordant negative), both persons HIV-infected (HIV concordant positive), or one HIV-infected and the other HIV-uninfected (HIV discordant). Counselling messages are tailored around the couple’s HIV status. In both individual and couple HCT models, testing can be client- or provider-initiated, opt-in or opt-out, and based in the clinic, home, workplace, or community.

Several reviews have explored the relationship between HCT and sexual behaviour in sub-Saharan Africa [11–15]. They find that there is a strong and consistent increase in condom uptake among persons learning they are HIV-infected. This effect is even stronger in couple HCT, especially for HIV-discordant couples. However, the effect of HCT on sexual behaviour among HIV-uninfected persons who test alone is inconsistent.

Assessment of the impact of HCT on HIV acquisition is needed, as behaviours are imperfect proxies for HIV acquisition. Sexual behaviour is based on self-report, which can be biased from inaccurate recall and social desirability. Even accurate self-report may not perfectly predict HIV acquisition. Consistent condom use is associated with substantial reductions, but not elimination, of acquisition risk [16–20]. Similarly, questions about condom use or number of partners may mask certain behaviours, such as sero-sorting or selecting partners perceived to be less risky. Thus, direct estimates of the effect of HCT on HIV acquisition are necessary.

We conducted a systematic review to assess the impact of HCT on HIV acquisition among HIV-uninfected persons in sub-Saharan Africa. Specifically, we reviewed articles comparing A) sites that offered full HCT to sites that did not, B) persons who received HCT to persons who did not, and C) persons who received HCT individually to those who received HCT as a couple. We also assessed the quality of each article, including research design and analysis.

Methods

In this review, we sought to systematically identify all published articles from sub-Saharan Africa that assessed the impact of HCT on HIV acquisition. HCT was defined as a process that included pre-test counselling, HIV testing, and post-testing counselling, including return of test results. Persons who tested, but did not receive their results were classified as not having received HCT. Articles were included if they met the following search criteria:

Conducted in sub-Saharan Africa

Evaluated the impact of HCT among HIV-uninfected persons

Had a longitudinal study design

Had an HIV acquisition endpoint

Compared settings that provided HCT to settings that did not (Strata A), compared persons who were exposed to HCT to persons who were not (Strata B), or compared couple HCT to individual HCT (Strata C)

Further restrictions were not made based on the nature of HCT or on methodologic criteria, such as study design or analytic methods.

On August 9, 2013, PubMed and PsychINFO were searched using the following search terms: “HIV AND (acquisition OR incidence) AND testing AND counselling” to identify abstracts for review. Date of publication was not an inclusion criterion. A trained research assistant screened all abstracts and identified those that potentially met review criteria. Ambiguous abstracts, such as those that reported HIV acquisition in only one sub-group, were included at this stage. These abstracts were then screened by an epidemiologist, and when necessary the full manuscripts were reviewed. Reference lists of included manuscripts were reviewed for additional articles that potentially met inclusion criteria. These additional articles were screened using the same procedures. Duplicates were removed.

Information on the study settings, populations, study designs, intervention and comparison, and HIV acquisition measures were abstracted. Setting attributes included country, year of data collection, and whether HCT was workplace, community, home, or clinic-based. Population characteristics included age, gender, and risk groups, such as general population or key populations (e.g. sex workers, men who have sex with men, or injection drug users).

Study designs were classified as randomised, pre/post, or exposed/unexposed cohorts. Pre/post comparisons applied to persons who initially did not receive HCT and later did receive HCT. Exposed/unexposed comparisons compared persons who received HCT to those who did not receive HCT. Measures of HIV incidence were abstracted from articles as incidence rate ratios and/or hazard ratios and ninety five percent confidence intervals. Crude, adjusted, and inverse probability weighted effect measures were reported separately. When multiple sub-populations or types of analyses were included, each were reported separately. When available, sub-population effect measures were also reported. If the original authors had not calculated these measures, but sufficient information was available, we conducted these calculations using Open Epi (www.OpenEpi.com).

Information on study quality and bias was abstracted, as well. To assess the possibility of exposure misclassification, we assessed whether HCT status was ascertained via self-report or from clinical or study records. The number of times HCT status was ascertained was also assessed. To explore the possibility of confounding, we abstracted adjustment variables, including whether sexual risk behaviours were included. To assess the possibility of selection bias, the proportion of eligible persons that participated and the proportion of participants who were retained were abstracted. To determine the amount of information each study was contributing, the number of seroconversion events was abstracted.

Study characteristics were entered into a Microsoft Access database. Two trained research assistants reviewed each article independently. The two databases were compared for consistency by the epidemiologist, who adjudicated discrepancies. She re-read all articles to validate all information in the final database.

Meta-analysis was not conducted because the studies were heterogeneous in terms of populations, study designs, effect measures, and nature of HCT. Therefore, all assessments are descriptive. Our review procedures were not registered.

Results

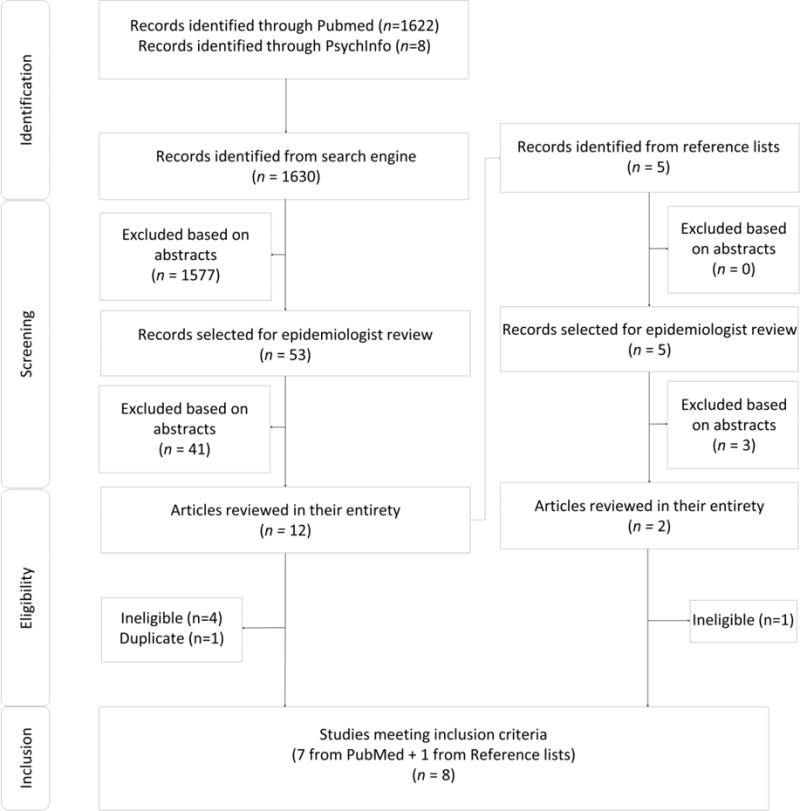

The PubMed search yielded 1622 abstracts and the PsychINFO search yielded eight abstracts. Of these abstracts, 53 were identified as potentially eligible based on the abstracts and 12 were reviewed in their entirety. One was excluded as it reported on a duplicate cohort, four were excluded for lacking a comparison population, incidence information, or both, and seven met all inclusion criteria. Five additional articles were identified for review from the reference lists. Of these, two were reviewed in their entirety. One was excluded for lacking a longitudinal design and one met all inclusion criteria. In total there were eight articles included in the review (Figure 1). Of these eight articles, one was in strata A, a comparison of sites with and without HCT [21], five were in strata B, comparisons of individuals who received HCT to those who did not [22–26], and two were in strata C, comparisons of individuals who received individual HCT to those who received couple HCT [27,28].

Figure 1. Article Inclusion and Exclusion.

Figure 1 displays articles identified, screened, eligible, and included.

Settings and Populations

Six articles relied on data collected before the introduction of PEPFAR in 2003 [21, 22, 24–26, 28], and two relied on data collected after this period [23, 27] (Table 1). Studies were conducted in Uganda [22, 24, 27], Rwanda [28], Zimbabwe [21, 25, 26], and South Africa [23]. Data were ascertained from five home-based settings [22–25, 27], two workplace settings [21, 26], and one clinical setting [28]. No studies were conducted exclusively among injecting drug users, sex workers, or men who have sex with men. All were conducted among the general population with most HIV acquisition risk presumed to be through heterosexual contact. The workplace-based studies were conducted predominantly among men [21, 26], the home-based studies were conducted among men and women [22–25, 27] and the clinical study was conducted among women attending antenatal or pediatric services [28]. One study was restricted to youth 15–24 years old [23], and the rest were conducted in a broader range of adult ages with minimum ages of 13–18 years and maximum ages of 35 to >60 years. In all studies, HCT was conducted by trained counselors.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics

| Citation | Year Conducted | Country | Setting of HCT | Setting of assessment | Gender | Age range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Sites receiving HCT versus sites not receiving HCT | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Corbett et al., 2007 | 2002–2004 | Zimbabwe | Workplace (intervention) clinic (control) | Workplace | Predominantly male | <24–>55 years |

|

| ||||||

| B. Individuals receiving HCT versus individuals not receiving HCT | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Machekano et al., 1998 | 1993–1995 | Zimbabwe | Workplace (pre-test), Work clinic (post-test) | Workplace | Male | <20–>46 |

| Matovu et al., 2005 | 1999–2000 | Uganda | Home | Population-based survey | Male and female | 15–49 years |

| Matovu et al., 2007 | 1994-not stated | Uganda | Home | Population-based survey | Male and female | 15–49 years |

| Sherr et al., 2007 | 1998–2003 | Zimbabwe | Mobile HCT | Population-based survey | Male and female | 17–54 years |

| Rosenberg et al., 2013 | 2006–2011 | South Africa | Not standardised | Population-based survey | Male and female | 15–24 years |

|

| ||||||

| C. Individuals receiving HCT alone versus individuals receiving HCT as a couple | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Allen et al., 1992 | 1988–1990 | Rwanda | Clinic | Clinic | Female | 18–35 years |

| Okiria et al., 2013 | 2006–2008 | Uganda | Home | Home-based testing programme | Male and female | 13–>60 years* |

Those 13–17 years who were married were considered emancipated minors and able to provide informed consent. Otherwise minimum age was 18.

Strata A

The assessment in strata A was a two-arm cluster randomised controlled trial conducted in Zimbabwean workplaces from 2002–2004. In both intervention and control sites, participants received pre-test counselling at their own workplace. In the intervention sites, persons were also able to receive HIV test results and post-test counselling at their workplaces, whereas in the control sites, persons received a voucher to off-site nearby clinics, a less convenient approach. These different approaches led to different uptake of HIV test results and post-test counselling: 5% in the control sites and 71% in interventions sites, resulting in HCT-exposed and unexposed groups in the intention to treat analysis. There were modest differences in the mean HIV incidence in the intervention (1.37 per 100 person years) and control sites (0.95 per 100 person years) for an intention to treat IRR of 1.44 (95% CI: 0.77, 2.71). In the per protocol analysis, the IRR was closer to the null: 1.34 (0.88, 2.06). Sixty-one seroconversion events were observed (Table 3). Approximately two thirds of eligible persons participated and, of these, approximately two thirds were retained.

Table 3.

Study Quality

| Citation | Randomised | Number of Sero-conversions | HCT (exposure) ascertainment | HIV (outcome) ascertainment | Number of times HCT ascertained | Participation rate | Retention rate | Adjustment methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Sites receiving HCT versus sites not receiving HCT | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Corbett et al., 2007 | Yes | 61 | Study records | Study records | Once | 72% | 69% | Baseline HIV prevalence and age |

|

| ||||||||

| B. Individuals receiving HCT versus individuals not receiving HCT | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Machekano et al., 1998 | No | 36 | Study records | Study records | More than once | Not stated | 85% | None |

| Matovu et al., 2005 | No | 77 | Household survey records | Household survey records | Once | 78% | 67% | None |

| Matovu et al., 2007 | No | 190 | Household survey records | Household survey records | More than once | Not stated | Not stated | Age, gender, marital status, education, current non-regular relationship, condom use in the past six months |

| Sherr et al., 2007 | No | 165 | Self-report | Household survey records | Once | 79% | 61% | Age and sex |

| Rosenberg et al., 2013 | No | 248 | Self-report | Household survey records | More than once | 54% of persons had sufficient information for inclusion in analysis | Age, gender, distance to the nearest clinic, education, sexual debut, condom use, number of sex partners, pregnancy, fatherhood | |

|

| ||||||||

| C. Individuals receiving HCT alone versus individuals receiving HCT as a couple | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Allen et al., 1992 | No | 29 | Study records | Study records | More than once | Not stated | 92% at 2 years | None |

| Okiria et al., 2013 | No | 106 | Programmatic records | Programmatic records | Once | Not stated | Not stated | HIV symptoms, age |

Strata B

Five studies were included from strata B. Two of these studies were conducted in Zimbabwe (1993–1995 and 1998–2003), two in Uganda (1994-non-specified and 1999–2000), and one in South Africa (2006–2011) (Table 2). All were observational. Four were conducted in homes in enumerated population-based household surveys and one was conducted in a workplace setting. One study had a pre/post design [26], three had exposed/unexposed designs [22, 24, 25], and one had both [23].

Table 2.

Study results

| Citation | Study Design | Comparison (C) | Intervention (I) | Sero-conversions/Person years; Incidence rate per 100 Person Years | Unadjusted and Adjusted Results (I versus C) (95% confidence intervals) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Sites receiving HCT versus sites not receiving HCT | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Corbett et al., 2007 | cluster randomised controlled trial | Pre-test counselling, risk assessment, and a voucher for results and post-test counselling at a free-standing clinic; uptake 5.2% | Pre-test counselling, risk assessment, testing, results, post-test counselling, and risk reduction planning in workplace; uptake 70.7% | C: 25/2462; 0.95 (mean/cluster) I: 36/2560; 1.37 (mean/cluster) |

IRR: 1.44 (0.79, 2.80), p=0.4 aIRR: 1.49 (0.77, 2.71), p=0.5 |

no effect of HCT on HIV acquisition |

|

| ||||||

| B. Individuals receiving HCT versus individuals not receiving HCT | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Machekano et al., 1998 | pre/post cohort | Pre-test counselling, tested for HIV but did not receive HIV test results or post-test counselling. | Pre-test counselling, tested for HIV, and received results and post-test counselling. | C:16/332; 4.82 I: 20/657; 3.04 |

IRR: 0.63 (0.31, 1.30), p=0.2 | trend towards HCT leading to lower HIV acquisition |

|

| ||||||

| Matovu et al., 2005 | exposed/unexposed cohort | Participants who provided blood but did not receive HIV test results and post-test counselling at the first household survey. | Participants who provided blood and received HIV test results and post-test counselling at the first household survey. | C: 35/2441; 1.4(overall) I: 42/2631; 1.6 (overall) C: 11/1001; 1.1 (males) I: 18/1166 1.5 (males) C: 24/1439; 1.7 (females) I: 24/1464; 1.6 (females) |

IRR:1.11 (0.71, 1.75), p=0.6 (overall)** IRR: 1.40 (0.67, 3.08), p=0.4 (males)** IRR: 0.98 (0.55, 1.74), p>0.9 (females)** |

no effect of HCT on HIV acquisition |

|

| ||||||

| Matovu et al., 2007 | exposed/unexposed cohort | Participants who did not accept home-based HCT results. (Entire population) | Participants who received home-based HCT results once or more than once (Entire population) | C: 66/4038; 1.6 (never) I: 76/4658; 1.6 (once); I: 48/3488; 1.4 (repeat) |

IRR: 1.00 (0.72, 1.39), p>0.9 (once v. never)** aIRR: 1.00 (0.72, 1.39) (once v. never) IRR: 0.84 (0.58, 1.22), p=0.4 (once v. never)** aIRR: 0.85 (0.58, 1.23) (repeat v. never) |

no effect of HCT on HIV acquisition |

| Participants who did not accept home-based HCT results. (Those with ≥2 partners) | Participants who received home-based HCT results once or more than once (Those with >2 partners) | C: 16/560; 2.9 (never) I: 9/631; 1.4 (once) I: 7.641; 1.1 (repeat) |

IRR: 0.50, (0.21, 1.12), p=0.1 (once v. never)** aIRR: 0.58 (0.25, 1.37) (once v. never) IRR: 0.38, (0.15, 0.91), 0.03 (repeat v. never)** aIRR: 0.49 (0.21, 1.17) (repeat v. never) |

trend towards HCT leading to lower HIV acquisition | ||

| Participants who did not accept home-based HCT results. (Those with only 1 partner) | Participants who received home-based HCT results once or more than once (Those with only 1 partner) | C: 50/3478; 1.4 (never) I: 67/4027; 1.7 (once) I: 41/2846; 1.4 (repeat) |

IRR: 1.16, (0.80, 1.67), p=0.4 (once v. never)** aIRR: 1.15, (0.79, 1.67) (once v. never) IRR: 1.00, (0.66, 1.51), p>0.9 (repeat v. never)** aIRR: 1.00 (0.66, 1.51) (repeat v. never) |

no effect of HCT on HIV acquisition | ||

|

| ||||||

| Sherr et al., 2007 | exposed/unexposed cohort | Persons who had never been tested or counseled | Participants who received pre-test counselling, testing, and post-test counselling | C: 147/8401; 1.75 (overall) I: 18/801; 2.25 (overall) C: 61/2950; 2.07 (males) I: 10/462; 2.16 (males) C: 86/5451; 1.58 (females) I: 8/339; 2.36 (females) |

IRR: 1.28 (0.77, 2.05), p=0.3 (overall)** aIRR: 1.30 (0.79, 2.14) (overall) IRR: 1.05 (0.51, 1.98), p=0.9 (males)** aIRR: 1.08 (0.62, 1.82) (males) IRR: 1.50 (0.68, 2.95), p=0.3 (females)** aIRR: 1.55 (0.63, 3.84) (females) |

no effect of HCT on HIV acquisition |

|

| ||||||

| Rosenberg et al., 2013 | exposed/unexposed and pre/post cohort | Participants who had not been tested for HIV and learned their results | Participants who been tested for HIV and learned their results | C: 131/4702; 2.79 I: 117/3834; 3.05 |

HR: 1.02 (95% CI: 0.79, 1.31), p=0.5 aHR: 0.65 (95% CI: 0.50, 0.86), p<0.01 ipwHR: 0.59 (95% CI: 0.45, 0.78), p<0.01 |

HCT leads to lower HIV acquisition, but only after adjustment |

|

| ||||||

| C. Individuals receiving HCT alone versus individuals receiving HCT as a couple | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Allen et al., 1992 | pre/post cohort | HIV-uninfected women before undergoing couple HCT | HIV-uninfected women after undergoing couple HCT | HCT: 12/293 4.1* cHCT: 5/278; 1.8* |

IRR: 0.44 (0.14, 1.22), p=0.1** | trend towards cHCT being more protective than no HCT |

| exposed/unexposed cohort | HIV-uninfected women who underwent individual HCT | HIV-uninfected women who underwent couple HCT | HCT: 24/706; 3.4* cHCT: 5/278; 1.8 |

IRR: 0.53 (0.18, 1.32), p=0.2** | trend towards cHCT being more protective than individual HCT | |

|

| ||||||

| Okiria et al., 2013 | exposed/unexposed cohort | Individual pre- and post-test counselling | Couple pre- and post-test counselling | HCT: 82/NA; 0.81 cHCT: 24NA; 0.25 HCT: 27/NA; 0.85 (women) cHCT 3/NA; 0.14 (women)*** HCT: 11/NA; 0.76 (men) cHCT: 7/NA; 0.38 (men) |

IRR: 0.31 (0.19, 0.48), p<0.01** IRR: 0.4 (0.22–0.75), p=<0.01 (women) aIRR: 0.4 (0.22–0.75) (women) IRR: 0.5 (0.24–1.05), p=0.07 (men) |

cHCT was more protective than individual HCT. |

based on hand calculations by the review authors.

confidence intervals calculated by review authors using Open Epi

Review authors believe original article may not have correctly reported this strata as the hand-calculated incidence rate ratio does not equal the reported rate ratio and the person years seem insufficient.

HCT=HIV counselling and testing; cHCT=couple HIV counselling and testing; C=comparison; I=intervention; IRR=incidence rate ratio; HR=hazard ratio; CI=confidence interval; PY=person year; a=adjusted; ipw=inverse probability weighted; NA=not available

HIV incidence rates in the full populations ranged from 1.5 [22, 24] to 3.5 [26] per 100 person years. In the full populations comparing those who received HCT to those who did not, IRRs ranged from 0.63 to 1.34 with all confidence intervals containing the null [22–26]. In analyses disaggregated by gender, IRRs among females ranged from 0.98 to 1.55 and IRRs among males ranged from 1.08 to 1.12; none were statistically significant. Only one assessment adjusted for sexual behaviour, and in this analysis HCT was found to be protective with a hazard ratio of 0.65 [23]. This study also used inverse probability weights to account for confounding and HCT was found to be protective with a hazard ratio of 0.59. In one study in which IRRs were disaggregated based on number of partners, there was a non-significant trend towards HCT being protective among those with more than one partner (IRR: 0.50) but not among those with only one partner (IRR: 1.16) [22].

All studies had methodologic limitations. None of these studies were randomised. Three did not account for confounding [24–26], one accounted for confounding in sub-analyses only [22], and one accounted for confounding in the main analysis [23]. Participation rates were between 75% and 80% in the two studies that reported this figure [24, 25]. Retention rates were 60–85% in the three studies that reported this figure [24–26]. One retrospective study had sufficient information to include 54% of persons, with at least one baseline and follow-up endpoint [23]. In three studies, HCT status was ascertained based on study or clinic records [22, 24, 26], and in two studies it was based on self-report [23, 25]. Studies had between 36 and 248 seroconversion events.

Strata C: Couple HCT versus individual HCT

Two studies were identified within Strata C. The first was conducted in Rwanda from 1988–1990 among women presenting for antenatal and pediatric care at an urban hospital [28]. The second was conducted in Uganda from 2006–2008 as part of a home-based HCT programme [27]. From these two studies, four incidence rate ratios were abstracted. In Rwanda, one assessment compared HIV-uninfected women before couple HCT and after couple HCT (pre/post). A second compared HIV-uninfected women who received HCT alone to HIV-uninfected women who received HCT with a partner (unexposed/exposed). In both comparisons there was a trend toward cHCT being protective: pre-post IRR: 0.44 (95% CI: 0.14, 1.22); unexposed-exposed IRR: 0.53 (95% CI: 0.18, 1.32). In Uganda, HIV acquisition was compared between HIV-uninfected persons who tested individually to those who tested with a partner, with males and females analysed separately. Overall, testing with a partner was significantly protective: 0.31 (95% CI: 0.19, 0.48), with a stronger trend among females than males.

Combined these two studies had 135 seroconversion events. Incidence was 2.7 per 100 person years among HIV-discordant couples in Rwanda. Incidence was 0.5 per 100 person years among HIV-negative persons in unknown-status couples in Uganda. Neither study was randomised and neither adjusted for sexual behaviour. In both studies the participation rate was not stated.

Discussion

In spite of the rapid and substantial expansion of HCT in the sub-Saharan Africa, there are few assessments of the impact of HCT on HIV acquisition, and, to our knowledge, these few assessments have not been synthesised previously. Based on this small body of evidence, two key trends emerge. First, individual HCT does not consistently increase or decrease HIV acquisition risk. Second, couple HCT reduces HIV acquisition risk by approximately half compared to individual HCT. These findings must be interpreted cautiously and within a broader context, as this body of evidence is modest with imprecise estimates and possibilities of bias.

In all unadjusted analyses, when comparing those receiving HCT to those not receiving HCT, all results were close to the null and imprecise. These observations are consistent with comparable assessments in sub-Saharan Africa and other parts of the world. Project Accept, a large cluster randomised controlled trial in SSA and Asia, comparing areas of widespread community-based HCT to more limited clinic-based HCT, found no difference in HIV incidence at a community level [29]. In Western settings, among men who have sex with men, HCT has not been associated with decreased risk, especially among those who test repeatedly [30].

HIV-uninfected persons testing as a couple were less likely to acquire HIV than persons testing alone, a finding consistent with other evidence and models in the region. In an assessment in Uganda and Kenya, couples receiving couple HCT had substantially lower HIV incidence than historical controls [31]. Similarly, HIV-uninfected women in HIV-discordant couples who tested with their partners had lower HIV acquisition than HIV-uninfected women who tested alone, when assumptions were introduced about the proportion of HIV-uninfected women who were in HIV-discordant relationships [32]. These findings are consistent with a mathematical model suggesting that the scale-up of couple HCT could reduce HIV incidence in Zambia and Rwanda by 35–60% [33].

Our findings are also consistent with assessments of the behavioural impacts of HCT in sub-Saharan Africa. Individual HCT is associated with modest behaviour change in some HIV-uninfected populations, but not others [11]. However, couple HCT is consistently and strongly associated with uptake of consistent condom use, especially in HIV-discordant couples, with meta-analysed odds ratios in excess of 60 [12–14, 34, 35]. The greater effectiveness of couple HCT is likely due to the importance of dyadic interventions for sexual activity, which are dyadic behaviours [36–38]. Regardless of why, promoting couple HCT over individual HCT is a key policy implication. Although the World Health Organisation has endorsed couple HCT for the region, it remains the exception, not the norm. Several strategies, such as partner notification and community invitations have been effective for increasing couple HCT and could have important implications if brought to scale [39–41]. Such efforts would not only have benefits on reduced HIV incidence, but also on reaching global HIV targets, including the 90-90-90 goals, elimination of mother to child transmission [42–44]

Assessing the impact of HCT on HIV acquisition is methodologically challenging. First, all assessments of HIV acquisition require large cohorts followed for long periods with low, non-differential loss to follow-up. These longitudinal studies are time-consuming and expensive. Second, the impact of HCT on HIV acquisition cannot be assessed in randomised settings; deliberate withholding of HCT is unethical due to the incontrovertible benefits for HIV-infected persons. As a result, observational designs are typically employed, but these are less rigorous, especially without controlling for confounders. A third challenge is that both the primary exposure (HCT) and the primary outcome (HIV acquisition) require an HIV test. Thus, it is necessary to have independent ascertainment methods for establishing HCT (the exposure) and acquisition (the outcome). In some studies, the exposure is based on self-report, making it subject to information bias. And in some assessments, persons refuse to provide blood for outcome ascertainment, introducing potential bias.

In light of these methodologic challenges, this body of literature is small and methodologically weak. Only 8 articles are included with fewer than 1000 sero-conversion events, providing a limited foundation for drawing conclusions. Furthermore, all studies have important limitations. The study in Strata A was randomised at the cluster level. However, participation and retention were moderate, with possibilities for selection bias. All assessments in Strata B and C were non-randomised, and most did not control for key confounders: sexual behaviour and pregnancy. In the study that did control for these factors, HCT had no effect on HIV acquisition in unadjusted analysis but was protective in adjusted analysis [23]. This difference suggests that those who received HCT were at higher risk for HIV than those who did not; HCT helped lower the risk of testers (a higher risk population) to a level similar to that of non-testers (a lower risk population). It is not clear whether similar effects would have been observed, had other strata B studies controlled for these variables.

Integrating new biomedical advances into HCT is an important direction for future HCT programming. Most of these studies were conducted in the 1990s and early 2000s, prior to the findings that medical male circumcision and pre-exposure prophylaxis can be effective at reducing HIV acquisition rates among HIV-uninfected persons [7–9, 45–48]. As such, HCT in these studies was focused on behavioural prevention messages. To enhance its effectiveness, HCT can be used as a platform for providing referrals for biomedical prevention.

HCT with simple behavioural messages, when offered to HIV-uninfected persons without their sexual partners, is insufficient to consistently and substantially prevent HIV acquisition. However, HCT, when offered to HIV-infected persons, is critical for treatment initiation and subsequent reductions in transmissibility. Considering the effects of HCT on both HIV-uninfected and HIV-infected persons, HCT scale-up must continue. However, to maximise the prevention impacts, a paradigm shift towards couple HCT is needed, along with improved linkages to biomedical prevention for those who are HIV-uninfected and at high risk of HIV acquisition.

Message Box.

In spite of intensive scale-up of HIV counselling and testing (HCT) in sub-Saharan Africa, few well-designed studies have assessed the prevention impacts of HCT.

Individual HCT is neither consistently protective nor harmful.

Couple HCT is more protective than individual HCT.

Interventions beyond HCT are needed for substantial declines in HIV acquisition, including couple HCT.

Acknowledgments

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive license on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in STI and any other BMJPGL products and sub-licenses such use and exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our license http://group.bmj.com/products/journals/instructions-for-authors/licence-forms.

Conflict of Interest and Source of Funding

NER was supported by the DHHS/NIH/NIAID (T32 AI 007001-34), the UNC Hopkins Morehouse Tulane Fogarty Global Health Fellows Program (R25TW009340), the UNC Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI50410), and the National Institute of Mental Health (K99 MH104154-01A1)

Footnotes

Disclaimers: None

Author Contributions

NER conceptualised the study in collaboration with WCM. BH conducted the search and reviewed all abstracts. BH and JR reviewed and coded all full articles; NER adjudicated discrepancies. NER and BH wrote the first draft. All authors provided substantive edits to the manuscript and approved the final draft.

References

- 1.Parekh BS, Kalou MB, Alemnji G, Ou CY, Gershy-Damet GM, Nkengasong JN. Scaling up HIV rapid testing in developing countries: comprehensive approach for implementing quality assurance. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134(4):573–84. doi: 10.1309/AJCPTDIMFR00IKYX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO, UNAIDS, UNICEF. HIV Testing and Counseling. Towards Universal Access: Scaling up Priority HIV/AIDS Interventions in the Health Sector, Progress Report 2010. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNAIDS. Global Report: UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell S, Cockcroft A, Lamothe G, Andersson N. Equity in HIV testing: evidence from a cross-sectional study in ten Southern African countries. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2010;10:23. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-10-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bor J, Herbst AJ, Newell ML, Barnighausen T. Increases in adult life expectancy in rural South Africa: valuing the scale-up of HIV treatment. Science. 2013;339(6122):961–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1230413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Sitta R, Puren A. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: the ANRS 1265 Trial. PLoS medicine. 2005;2(11):e298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Makumbi F, Watya S, Nalugoda F, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9562):657–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, Agot K, Maclean I, Krieger JN, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9562):643–56. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health Republic of South Africa. National HIV Counselling and Testing Policy Guidelines. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Johnson BT, Bickham NL. Effects of HIV counseling and testing on sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review of published research, 1985–1997. American journal of public health. 1999;89(9):1397–405. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burton J, Darbes LA, Operario D. Couples-focused behavioral interventions for prevention of HIV: systematic review of the state of evidence. AIDS and behavior. 2010;14(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9471-4. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kennedy CE, Medley AM, Sweat MD, O’Reilly KR. Behavioural interventions for HIV positive prevention in developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2010;88(8):615–23. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.068213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaCroix JM, Pellowski JA, Lennon CA, Johnson BT. Behavioural interventions to reduce sexual risk for HIV in heterosexual couples: a meta-analysis. Sexually transmitted infections. 2013;89(8):620–7. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denison JA, O’Reilly KR, Schmid GP, Kennedy CE, Sweat MD. HIV voluntary counseling and testing and behavioral risk reduction in developing countries: a meta-analysis, 1990–2005. AIDS and behavior. 2008;12(3):363–73. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9349-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes JP, Baeten JM, Lingappa JR, Magaret AS, Wald A, de Bruyn G, et al. Determinants of per-coital-act HIV-1 infectivity among African HIV-1-serodiscordant couples. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2012;205(3):358–65. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weller SC. A meta-analysis of condom effectiveness in reducing sexually transmitted HIV. Social science & medicine. 1993;36(12):1635–44. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90352-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinkerton SD, Abramson PR. Effectiveness of condoms in preventing HIV transmission. Social science & medicine. 1997;44(9):1303–12. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00258-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis KR, Weller SC. The effectiveness of condoms in reducing heterosexual transmission of HIV. Family planning perspectives. 1999;31(6):272–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pinkerton SD, Abramson PR, Turk ME. Updated estimates of condom effectiveness. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care: JANAC. 1998;9(6):88–21. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(98)80012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corbett EL, Makamure B, Cheung YB, Dauya E, Matambo R, Bandason T, et al. HIV incidence during a cluster-randomized trial of two strategies providing voluntary counselling and testing at the workplace, Zimbabwe. AIDS. 2007;21(4):483–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280115402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matovu JK, Gray RH, Kiwanuka N, Kigozi G, Wabwire-Mangen F, Nalugoda F, et al. Repeat voluntary HIV counseling and testing (VCT), sexual risk behavior and HIV incidence in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS and behavior. 2007;11(1):71–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9170-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenberg NE, Westreich D, Barnighausen T, Miller WC, Behets F, Maman S, et al. Assessing the effect of HIV counselling and testing on HIV acquisition among South African youth. AIDS. 2013 doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000432454.68357.6a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matovu JK, Gray RH, Makumbi F, Wawer MJ, Serwadda D, Kigozi G, et al. Voluntary HIV counseling and testing acceptance, sexual risk behavior and HIV incidence in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS. 2005;19(5):503–11. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000162339.43310.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherr L, Lopman B, Kakowa M, Dube S, Chawira G, Nyamukapa C, et al. Voluntary counselling and testing: uptake, impact on sexual behaviour, and HIV incidence in a rural Zimbabwean cohort. AIDS. 2007;21(7):851–60. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32805e8711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Machekano R, McFarland W, Mbizvo MT, Bassett MT, Katzenstein D, Latif AS. Impact of HIV counselling and testing on HIV seroconversion and reported STD incidence among male factory workers in Harare, Zimbabwe. The Central African journal of medicine. 1998;44(4):98–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okiria AG, Okui O, Dutki M, Baryamutuma R, Nuwagaba CK, Kansiime E, et al. HIV incidence and factors associated with seroconversion in a rural community home based counseling and testing program in Eastern Uganda. AIDS and behavior. 2014;18(Suppl 1):S60–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0502-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allen S, Serufilira A, Bogaerts J, Van de Perre P, Nsengumuremyi F, Lindan C, et al. Confidential HIV testing and condom promotion in Africa. Impact on HIV and gonorrhea rates. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 1992;268(23):3338–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coates TJ, Kulich M, Celentano DD, Zelaya CE, Chariyalertsak S, Chingono A, et al. Effect of community-based voluntary counselling and testing on HIV incidence and social and behavioural outcomes (NIMH Project Accept; HPTN 043): a cluster-randomised trial. The Lancet Global health. 2014;2(5):e267–77. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70032-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacKellar DA, Valleroy LA, Secura GM, Bartholow BN, McFarland W, Shehan D, et al. Repeat HIV testing, risk behaviors, and HIV seroconversion among young men who have sex with men: a call to monitor and improve the practice of prevention. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2002;29(1):76–85. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200201010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Celum C, Baeten JM. Serodiscordancy and HIV prevention in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet. 2013;381(9877):1519–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen S, Tice J, Van de Perre P, Serufilira A, Hudes E, Nsengumuremyi F, et al. Effect of serotesting with counselling on condom use and seroconversion among HIV discordant couples in Africa. Bmj. 1992;304(6842):1605–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6842.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dunkle KL, Stephenson R, Karita E, Chomba E, Kayitenkore K, Vwalika C, et al. New heterosexually transmitted HIV infections in married or cohabiting couples in urban Zambia and Rwanda: an analysis of survey and clinical data. Lancet. 2008 Jun 28;371(9631):2183–91. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60953-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenberg NE, Pettifor AE, Bruyn GD, Westreich D, Delany-Moretlwe S, Behets F, et al. HIV Testing and Counseling Leads to Immediate Consistent Condom Use Among South African Stable HIV-Discordant Couples. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2013;62(2):226–33. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827971ca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bunnell R, Opio A, Musinguzi J, Kirungi W, Ekwaru P, Mishra V, et al. HIV transmission risk behavior among HIV-infected adults in Uganda: results of a nationally representative survey. Aids. 2008;22(5):617–24. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f56b53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewis MA, McBride CM, Pollak KI, Puleo E, Butterfield RM, Emmons KM. Understanding health behavior change among couples: an interdependence and communal coping approach. Social science & medicine. 2006;62(6):1369–80. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montgomery CM, Watts C, Pool R. HIV and dyadic intervention: an interdependence and communal coping analysis. PloS one. 2012;7(7):e40661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ware NC, Wyatt MA, Haberer JE, Baeten JM, Kintu A, Psaros C, et al. What’s love got to do with it? Explaining adherence to oral antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-serodiscordant couples. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2012;59(5):463–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824a060b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenberg NE, Mtande TK, Saidi F, Stanley C, Jere E, Paile L, et al. Recruiting male partners for couple HIV testing and counselling in Malawi’s option B+ programme: an unblinded randomised controlled trial. The Lancet HIV. 2015;2(11):e483–91. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00182-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wall K, Karita E, Nizam A, Bekan B, Sardar G, Casanova D, et al. Influence network effectiveness in promoting couples’ HIV voluntary counseling and testing in Kigali, Rwanda. AIDS. 2012;26(2):217–27. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834dc593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wall KM, Kilembe W, Nizam A, Vwalika C, Kautzman M, Chomba E, et al. Promotion of couples’ voluntary HIV counselling and testing in Lusaka, Zambia by influence network leaders and agents. BMJ open. 2012;2(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Were W, Mermin J, Nafuna W, Awor AC, Bechange S, et al. Undiagnosed HIV Infection and Couple HIV Discordance Among Household Members of HIV-Infected People Receiving Antiretroviral Therapy in Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006 Sep;43(1):91–5. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000225021.81384.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stirratt MJ, Remien RH, Smith A, Copeland OQ, Dolezal C, Krieger D. The role of HIV serostatus disclosure in antiretroviral medication adherence. AIDS Behav. 2006 Sep;10(5):483–93. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aluisio AR, Bosire R, Betz B, Gatuguta A, Kiarie JN, Nduati R, et al. Male Partner Participation in Antenatal Clinic Services is Associated with Improved HIV-free survival Among Infants in Nairobi, Kenya: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016 Apr 26; doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baeten J, Celum C. Oral antiretroviral chemoprophylaxis: current status. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2012;7(6):514–9. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3283582d30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367(5):399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, Agot K, Lombaard J, Kapiga S, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367(5):411–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abdool Karim SS, Richardson BA, Ramjee G, Hoffman IF, Chirenje ZM, Taha T, et al. Safety and effectiveness of BufferGel and 0.5% PRO2000 gel for the prevention of HIV infection in women. AIDS. 2011;25(7):957–6. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834541d9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]