Abstract

Tachyplesin I is a cationic peptide isolated from hemocytes of the horseshoe crab and its anti-tumor activity has been demonstrated in several tumor cells. However, there is limited information providing the global effects and mechanisms of tachyplesin I on glioblastoma multiforme (GBM). Here, by using two complementary proteomic strategies (2D-DIGE and dimethyl isotope labeling-based shotgun proteomics), we explored the effect of tachyplesin I on the proteome of gliomaspheres, a three-dimensional growth model formed by a GBM cell line U251. In total, the expression levels of 192 proteins were found to be significantly altered by tachyplesin I treatment. Gene ontology (GO) analysis revealed that many of them were cytoskeleton proteins and lysosomal acid hydrolases, and the mostly altered biological process was related to cellular metabolism, especially glycolysis. Moreover, we built protein–protein interaction network of these proteins and suggested the important role of DNA topoisomerase 2-alpha (TOP2A) in the signal-transduction cascade of tachyplesin I. In conclusion, we propose that tachyplesin I might down-regulate cathepsins in lysosomes and up-regulate TOP2A to inhibit migration and promote apoptosis in glioma, thus contribute to its anti-tumor function. Our results suggest tachyplesin I is a potential candidate for treatment of glioma.

Keywords: tachyplesin I, glioblastoma multiforme, cancer stem cell, stable isotope dimethyl labeling, parallel reaction monitoring

1. Introduction

Gliomas, the most common group of primary brain tumors, are subcategorized into astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas and ependymomas. According to World Health Organization (WHO), glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), the most malignant and lethal form of brain tumor in adults, is a grade IV astrocytoma with very high morbidity and mortality. The disease has a very poor prognosis with short median survival, only about 15 months, despite current multimodal treatment including maximal surgical resection if feasible, followed by a combination of radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy [1]. Therefore, it is imperative to present new and more effective therapeutic interventions to better control GBM.

In fact, the short median survival of GBM is largely ascribed to the inevitable tumor recurrence. Recent research has paid more attention to the existence of glioma stem cells (GSCs), which are a subgroup of tumor cells with properties that resemble those of neural stem cells, and are able to drive tumorigenesis and likely contribute to rapid tumor recurrence [2]. These cells were first described more than ten years ago and have been demonstrated with the capability of multi-lineage differentiation, self-renewal and extensive proliferation [3]. In addition, GSCs can endure and even thrive in stressful tumor conditions, including hypoxia, oxidative stress, inflammation, acidic stress, and low glucose [4]. Moreover, their resistance to conventional therapy and promotion of tumor angiogenesis also influence clinical practice [5,6]. Thus, GSCs provide new insight into the strategy in GBM therapy.

Three-dimensional growth model, a growth sphere formed by cancer stem cells under specific culture conditions in vitro, is a more reasonable model for tumor biology and drug screening in vitro studies [7,8]. Likewise, GSCs also have the characteristic of forming spheres and clinical data show that the rates of existence of gliomaspheres were more prominent in high grade malignant gliomas [9]. Previously, we isolated gliomaspheres from U251 glioma cell lines and tried to apply it for drug screening. We found that there were undifferentiated GSCs and differentiated cancer cells with different differentiation degrees in gliomaspheres, which were similar to the growth state of glioma in vivo [10]. Our previous data showed that gliomaspheres express stem cell biomarkers nestin and CD133, which are certain phenotypes of GSC, and tachyplesin I inhibited the viability and proliferation of gliomaspheres dose dependently, by damaging the plasma membrane and inducing differentiation of GSCs [11]. These findings indicate that tachyplesin I is a potential anti-tumor drug which may be used in GBM therapy.

Tachyplesin I, a cationic peptide with 17 residues (NH2-K-W-C-F-R-V-C-Y-R-G-I-C-Y-I-R-R-C-R-CONH2), was originally isolated from hemocytes of the horseshoe crab (Tachypleus tridentatus) [12]. It has the ability of anti-enzymatic hydrolysis due to two disulfide-stabilized β-hairpins [13]. Several studies have demonstrated that tachyplesin I can inhibit the proliferation and affect the differentiation of tumor cells, such as hepatocarcinoma, gastric adenocarcinoma and leukemia [14,15]. This peptide has also been demonstrated to activate the classic complement pathway to lyse and kill tumor cells and to alter the expression of tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes to induce cell differentiation and reverse the malignant phenotype [16,17]. Most interestingly, the negatively charged components of cancer cells, which are quite different from neutral normal cells, are more vulnerable by the positively charged cationic peptides, including tachyplesin I. The electrostatic attraction between cancer cells and cationic peptides is believed to play a major role in the selective disruption of cancer cell membranes, which avoids traditional mechanism of drug resistance [18].

Although the anti-tumor effect of tachyplesin I has been studied to some extent, the mechanism of anti-tumor activity in GBM is largely unknown. In recent years, proteomics has been shown to be a powerful approach for exploring the molecular mechanisms of anti-tumor drugs. In this study, our primary goal was to identify the changes in protein expression profile of U251 gliomaspheres under the treatment of tachyplesin I, which may help us to better understand the molecular mechanisms underlying potential anti-glioma drugs. Here, both gel-based and shotgun proteomic approaches were performed to gain a higher proteome coverage and better quantification results [19]. Proteomic analysis using two dimension difference gel electrophoresis (2D-DIGE) and stable isotope dimethyl labeling based Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) revealed that 192 proteins were differentially expressed in U251 gliomaspheres in response to tachyplesin I. Biological involvement of these proteins are further discussed in detail through signaling pathways and protein–protein interaction network analysis. Furthermore, the expression of cathepsins in lysosomes and TOP2A was further validated by Western blot and PRM, due to their important involvement in the anti-tumor activity of tachyplesin I, by inhibiting migration and promote apoptosis of glioma cells, respectively.

2. Results

2.1. Protein Expression Profile of Tachyplesin I Treated U251 Gliomaspheres Using 2D-DIGE Analysis

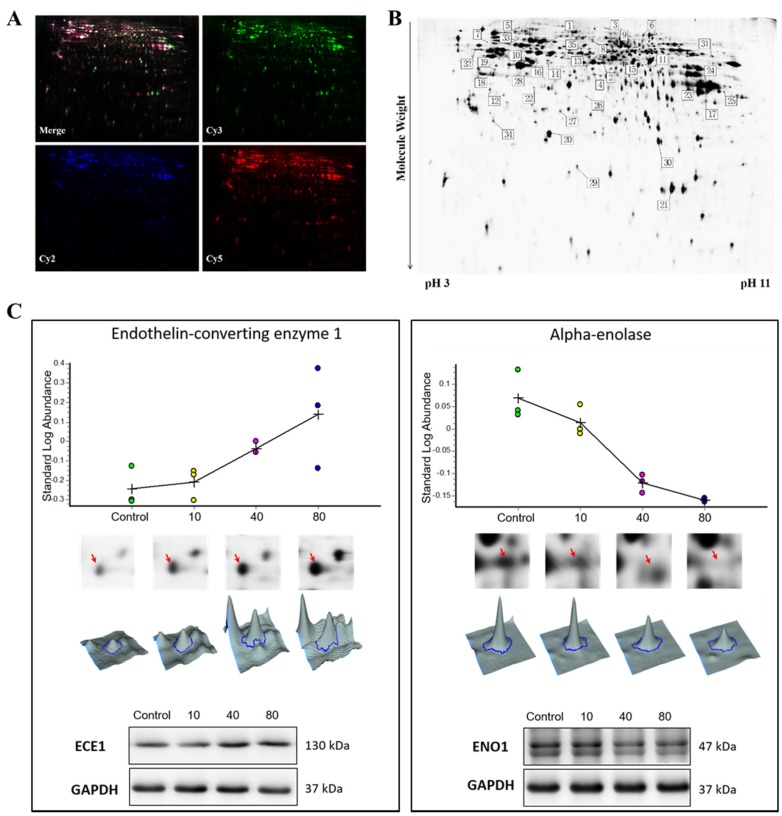

The 2D-DIGE images, which were scanned at the wavelengths of 488/520, 532/580, and 633/670 nm, visualize the protein expression pattern in the cells (Figure 1A). In the image analysis, 1298 protein spots were detected. Of these, 35 spots with fold change larger than ±1.5 were considered significantly altered in tachyplesin I treated U251 gliomaspheres compared with untreated control (Figure 1B). Among the protein spots that satisfied the statistical criteria, 26 were confidently identified by MALDI-TOF/TOF analysis. Out of 26 identified proteins, 13 were up-regulated while the others were down-regulated in tachyplesin I treated U251 gliomaspheres. Up-regulated proteins were mainly involved in regulation of cell cycle and apoptosis, and cytoskeleton proteins (Table 1). Conversely, down-regulated proteins were involved in glycolysis, response to stimulus and calcium or ion binding (Table 1). Several proteins (Vimentin, Phosphate carrier protein, mitochondrial and Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha) were identified more than once in different location of 2D-DIGE gel, suggesting diverse protein isoforms, such as the occurrence of post-translational modification. Representative images of one up-regulated protein endothelin-converting enzyme 1 (ECE1) and one down-regulated protein alpha-enolase (ENO1) in different dose groups are shown in Figure 1C. Western blot assay was performed to confirm the results obtained from 2D-DIGE experiment and the results were consistent (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Two dimension difference gel electrophoresis (2D-DIGE) analysis of U251 gliomaspheres after treated with tachyplesin I. (A) Representative scanned 2D-DIGE images of Cy2, Cy3, and Cy5, and their overlay derived from a single gel; (B) Representative 2D-DIGE protein profiles with the protein spots marked as differentially regulated in U251 gliomaspheres treated with tachyplesin I. Information about the proteins corresponding to the spot numbers is listed in Table 1; (C) The expression levels of endothelin-converting enzyme 1 (ECE1) and alpha-enolase (ENO1) in U251 gliomaspheres treated by 0, 10, 40 and 80 μg/mL of tachyplesin I for 24 h are visualized by protein abundance maps (first panel), 2-DE images (second panel), three-dimensional spot images (third panel) and validated by Western blot (bottom panel). GAPDH was used as a loading control.

Table 1.

Regulated proteins of tachyplesin I treated U251 gliomaspheres in the 2D-DIGE study.

| Up-Regulated Proteins of Tachyplesin I Treated U251 Gliomaspheres in the 2D-DIGE Study | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. a | Gene Name | Uniprot ID | Protein Name | Mascot Score | Peptides | Protein MW | pI Value | Ratio/p Value b | Ratio/p Value b |

| 10 vs. 0 c | 40 vs. 0 c | ||||||||

| Regulation of cell cycle or apoptosis d | |||||||||

| 2 | PHGDH | O43175 | d-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase | 104 | 3 | 57,356 | 6.3 | 1.54/0.003 | 1.69/0.017 |

| 5 | MSH2 | P43246 | DNA mismatch repair protein Msh2 | 93 | 2 | 104,743 | 5.8 | 1.21/0.009 | 1.77/0.035 |

| 19 | SESN3 | P58005 | Sestrin-3 | 201 | 4 | 57,291 | 6.3 | 1.52/0.036 | 2.01/0.027 |

| 31 | CKAP2 | Q8WWK9 | Cytoskeleton-associated protein 2 | 76 | 7 | 76,987 | 9.4 | ND e | 1.52/0.039 |

| 35 | ECE1 | P42892 | Endothelin-converting enzyme 1 | 46 | 1 | 87,164 | 5.9 | 1.58/0.038 | 3.31/0.026 |

| Cytoskeletal protein d | |||||||||

| 3 | VIM | P08670 | Vimentin | 407 | 12 | 53,676 | 4.9 | ND | 1.64/0.022 |

| 4 | EEF1G | P26641 | Elongation factor 1-gamma | 47 | 2 | 50,429 | 6.3 | ND | 1.51/0.005 |

| 9 | EZR | P15311 | Ezrin | 168 | 3 | 69,484 | 5.9 | 1.03/0.024 | 1.63/0.046 |

| 10 | VIM | P08670 | Vimentin | 524 | 15 | 53,676 | 4.9 | ND | 1.58/0.041 |

| Protein biosynthesis d | |||||||||

| 6 | EEF2 | P13639 | Elongation factor 2 | 60 | 1 | 96,246 | 6.4 | ND | 1.55/0.044 |

| 21 | PPIA | P62937 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase A | 195 | 16 | 18,229 | 9 | 1.26/0.017 | 1.52/0.028 |

| Transport d | |||||||||

| 23 | SLC25A3 | F8VVM2 | Phosphate carrier protein, mitochondrial | 90 | 5 | 36,161 | 9.3 | ND | 1.72/0.034 |

| 25 | SLC25A3 | F8VVM2 | Phosphate carrier protein, mitochondrial | 183 | 9 | 36,161 | 9.3 | ND | 1.63/0.016 |

| Down-Regulated Proteins of Tachyplesin I Treated U251 Gliomaspheres in the 2D-DIGE Study | |||||||||

| Calcium or iron ion binding protein d | |||||||||

| 7 | EPS15 | P42566 | Epidermal growth factor receptor substrate 15 | 109 | 5 | 98,656 | 5.1 | ND e | −1.88/0.004 |

| 13 | P4HA1 | P13674 | Prolyl 4-hydroxylase subunit alpha-1 | 86 | 5 | 61,296 | 5.6 | −1.51/0.007 | −2.37/0.045 |

| Regulation of cell apoptosis or proliferation d | |||||||||

| 12 | ANXA5 | P08758 | Annexin A5 | 273 | 13 | 35,971 | 4.8 | ND | −1.74/0.033 |

| 20 | GSTP1 | P09211 | Glutathione S-transferase P | 339 | 21 | 23,569 | 5.3 | ND | −1.66/0.001 |

| 33 | COL4A3BP | Q9Y5P4 | Collagen type IV alpha-3-binding protein | 250 | 7 | 70,835 | 5.5 | ND | −1.64/0.033 |

| 34 | ARHGDIA | P52565 | Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor 1 | 236 | 16 | 23,250 | 4.9 | −1.23/0.037 | −2.64/0.047 |

| Response to stimulus d | |||||||||

| 14 | GNAQ | P50148 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha | 193 | 9 | 42,142 | 5.7 | ND | −1.61/0.037 |

| 16 | GNAQ | P50148 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha | 294 | 12 | 42,142 | 5.7 | ND | −1.59/0.047 |

| 28 | GNAQ | P50148 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha | 182 | 7 | 42,142 | 5.7 | −1.33/0.028 | −1.53/0.036 |

| Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis d | |||||||||

| 15 | ENO1 | P06733 | Alpha-enolase | 40 | 3 | 47,481 | 7.7 | −1.04/0.005 | −1.92/0.054 |

| 17 | PGK1 | P00558 | Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | 209 | 7 | 44,985 | 9.2 | −1.68/0.025 | −2.89/0.051 |

| 30 | TPI1 | P60174 | Triosephosphate isomerase | 375 | 15 | 31,057 | 5.6 | −1.17/0.048 | −1.88/0.028 |

| Ribosomal protein d | |||||||||

| 18 | RPSA | P08865 | 40S ribosomal protein SA | 171 | 9 | 32,947 | 4.6 | −1.49/0.036 | −1.89/0.027 |

a No.—The numbers correspond to the spot numbers indicated in Figure 1B; b Average ratios of spot abundance of tachyplesin I-treated samples relative to the control, represent data from three separate experiments and student’s t test p values are given as a measure of confidence for the ratio of each spot measured; c 0: control group; 10: 10 μg/mL dose group; 40: 40 μg/mL dose group; d Functional categories according to Gene ontology and panther biological process annotations; e ND, not detected or p value > 0.5.

2.2. Relative Quantification Using Dimethyl Labeling Based LC-MS/MS Analysis

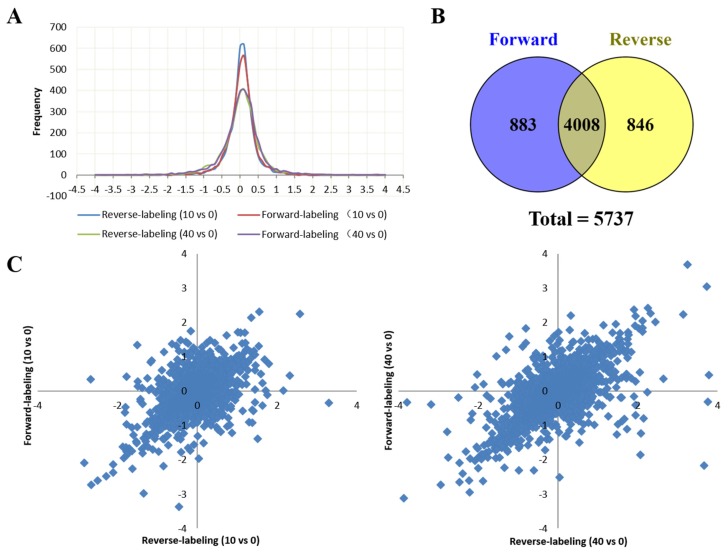

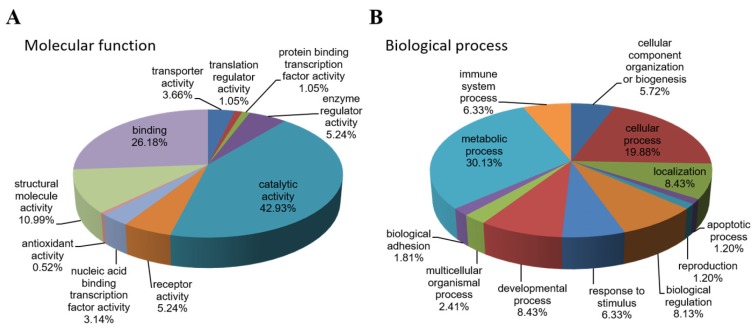

Peptide samples from the control, and 10 μg/mL and 40 μg/mL tachyplesin I-treated U251 gliomaspheres were labeled with dimethyl stable isotope tags. To obtain reliable quantification results, we conducted one forward and one reverse dimethyl labeling experiments. A total of 74,240 peptides from 4891 proteins were identified in the forward-labeling samples and 73,892 peptides from 4854 proteins in the reverse-labeling samples (Supplementary Materials Tables S1–S4). In both forward and reverse labeling experiment, the labeled peptides account for more than 99.8% of total identified peptides, indicating a good labeling efficiency. A total of 5737 proteins were reliably quantified in both the forward and reverse labeling experiments, of which 4008 proteins were overlapped (Figure 2B). The protein ratios of L/H and M/H in the forward labeling experiment and protein ratios of M/L and H/L in the reverse labeling experiment indicate the relative abundance of proteins in 10 μg/mL and 40 μg/mL tachyplesin I-treated groups compared to the control. The log2 transformed protein ratios between two different experimental groups all form a symmetric distribution curve with the peak around zero (the original ratio = 1) (Figure 2A), and proteins that were increased or decreased in the forward-labeling experiment were also increased or decreased in the reverse-labeling experiment (Figure 2C), suggesting that there was no bias in the labeling and LC-MS experiments. Only those proteins with fold changes >2 and quantified in both forward and reverse labeling experiments were reported as differentially expressed proteins. Among 4088 proteins, the expression levels of 166 were significantly altered by tachyplesin I treatment. Among them, 55 were up-regulated (Table 2) while 111 proteins were down-regulated (Table 2). Figure 2D shows representative mass spectrometric results for the identification and quantification of the peptide DPDAQPGGELMLGGTDSK from cathepsin D, which clearly reveals the down-regulation of this protein in both sets of experiments.

Figure 2.

Dimethyl labeling based Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis of U251 gliomaspheres after treated with tachyplesin I. (A) Distribution of quantified protein log2 ratios; (B) A Venn diagram shows the number of proteins identified in either forward or reverse labeling experiment, as well as the overlap between them; (C) A scatter plot showing the forward (y-axis) and reverse (x-axis) dimethyl labeling log2 ratios for the 4008 proteins that were identified and quantified in both experiment, the left panel corresponds to 10 μg/mL group versus control, the right panel corresponds to 40 μg/mL group versus control. The values for each protein are shown as a blue diamond; (D) Representative mass spectrometric image revealing the tachyplesin I-induced down regulation of cathepsin D. Shown are the MS for the peptide DPDAQPGGELMLGGTDSK of cathepsin D from the forward (left panel) and reverse (right panel) dimethyl labeling samples.

Table 2.

List of proteins with altered expression in U251 gliomaspheres after treatment of tachyplesin I using dimethyl labeling quantitative proteomic analysis.

| The 55 Up-Regulated Proteins Expressed More Than 2 Folds (<1% FDR) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Name | Uniprot ID | Protein Name | Coverage (%) a | Unique Peptides a | 10 vs. 0 Ratio b | 40 vs. 0 Ratio b | Protein Class c | ||

| Forward | Reverse | Forward | Reverse | ||||||

| SPP1 | P10451 | Osteopontin | 33.12 | 5 | 4.961 | 2.943 | 12.876 | 9.484 | cytokine |

| ITGB3 | P05106 | Integrin beta-3 | 5.20 | 3 | 4.754 | 5.953 | 13.279 | 28.714 | receptor, extracellular matrix glycoprotein |

| EPS8 | Q12929 | Epidermal growth factor receptor kinase substrate 8 | 4.01 | 3 | 4.403 | 2.549 | 2.220 | 2.305 | transmembrane receptor regulatory/adaptor protein |

| MCM5 | B1AHB1 | DNA helicase | 5.50 | 3 | 3.304 | 2.022 | 3.801 | 2.194 | DNA helicase |

| DKK1 | O94907 | Dickkopf-related protein 1 | 11.28 | 4 | 3.267 | 2.278 | 3.885 | 2.732 | developmental protein, growth factor activity |

| MCM4 | P33991 | DNA replication licensing factor MCM4 | 7.76 | 4 | 3.248 | 2.119 | 5.189 | 3.723 | DNA binding protein |

| NUSAP1 | Q9BXS6 | Nucleolar and spindle-associated protein 1 | 18.14 | 5 | 2.661 | 2.293 | 3.121 | 3.405 | microtubule-associated protein |

| DHFR | P00374 | Dihydrofolate reductase | 24.06 | 4 | 2.616 | 2.168 | 2.398 | 2.472 | reductase |

| TOP2A | P11388 | DNA topoisomerase 2-alpha | 12.93 | 12 | 2.490 | 2.916 | 3.259 | 2.582 | DNA topoisomerase, enzyme modulator |

| MKI67 | A0A087WV66 | Antigen KI-67 | 12.66 | 24 | 2.396 | 1.870 | 2.688 | 2.047 | regulation of cell proliferation |

| TFRC | P02786 | Transferrin receptor protein 1 | 35.79 | 23 | 2.323 | 2.398 | 2.906 | 2.879 | receptor |

| AIM1 | Q9Y4K1 | Absent in melanoma 1 protein | 21.53 | 25 | 2.298 | 2.329 | 4.036 | 5.403 | carbohydrate binding protein |

| ECE1 | P42892 | Endothelin-converting enzyme 1 | 15.19 | 8 | 2.260 | 2.671 | 3.557 | 4.070 | metalloprotease |

| SYNJ2 | O15056 | Synaptojanin-2 | 8.76 | 11 | 2.239 | 2.501 | 5.349 | 4.740 | phosphatase |

| KIF11 | P52732 | Kinesin-like protein KIF11 | 2.37 | 2 | 2.199 | 2.274 | 2.469 | 2.182 | microtubule binding motor protein |

| DST | Q03001 | Dystonin | 23.49 | 21 | 2.113 | 1.596 | 2.614 | 2.051 | non-motor actin binding protein |

| UPP1 | Q16831 | Uridine phosphorylase 1 | 46.45 | 11 | 2.078 | 2.712 | 2.209 | 3.577 | phosphorylase |

| IGFBP5 | P24593 | Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 5 | 20.59 | 5 | 2.070 | 2.060 | 4.816 | 4.967 | cell communication |

| RRM2 | P31350 | Ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase subunit M2 | 34.45 | 11 | 2.030 | 1.981 | 2.286 | 2.423 | reductase |

| CD70 | P32970 | CD70 antigen | 35.23 | 6 | 1.995 | 2.167 | 3.725 | 3.808 | cell communication |

| MDK | E9PPJ5 | Midkine (Fragment) | 27.48 | 2 | 1.935 | 2.538 | 3.569 | 4.336 | cytokine |

| HMGCS1 | Q01581 | Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase, cytoplasmic | 42.88 | 17 | 1.929 | 1.939 | 3.322 | 4.339 | transferase, lyase |

| DCLK1 | Q5VZY9 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase DCLK1 | 10.74 | 3 | 1.899 | 3.222 | 4.721 | 8.819 | non-receptor serine/threonine protein kinase |

| MCM7 | P33993 | DNA replication licensing factor MCM7 | 13.21 | 7 | 1.879 | 1.963 | 2.451 | 2.470 | DNA helicase |

| PODXL | O00592 | Podocalyxin | 2.33 | 1 | 1.870 | 2.234 | 2.474 | 2.856 | regulation of adhesion and cell morphology |

| MCM2 | H0Y8E6 | DNA replication licensing factor MCM2 (Fragment) | 8.25 | 6 | 1.865 | 1.513 | 2.167 | 2.664 | DNA helicase |

| LPL | P06858 | Lipoprotein lipase | 34.11 | 12 | 1.848 | 2.078 | 4.136 | 4.351 | storage protein |

| VSNL1 | P62760 | Visinin-like protein 1 | 24.08 | 4 | 1.805 | 2.260 | 3.231 | 2.926 | cell communication |

| MCM6 | Q14566 | DNA replication licensing factor MCM6 | 9.01 | 4 | 1.765 | 2.208 | 2.606 | 3.031 | DNA helicase |

| GPC1 | P35052 | Glypican-1 | 33.69 | 14 | 1.745 | 1.665 | 2.861 | 3.347 | cell division and growth regulation |

| TACC3 | Q9Y6A5 | Transforming acidic coiled-coil-containing protein 3 | 3.22 | 2 | 1.735 | 2.068 | 2.563 | 2.322 | cytoskeleton |

| TNC | P24821 | Tenascin | 40.16 | 5 | 1.730 | 1.803 | 2.327 | 2.112 | signaling molecule |

| PLAT | P00750 | Tissue-type plasminogen activator | 24.73 | 12 | 1.729 | 3.475 | 8.267 | 13.172 | receptor, calmodulin |

| GATM | P50440 | Glycine amidinotransferase, mitochondrial | 28.61 | 9 | 1.704 | 1.793 | 2.591 | 2.740 | catalyze creatine biosynthesis |

| SERPINE1 | P05121 | Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 | 21.14 | 7 | 1.695 | 1.448 | 4.539 | 3.853 | serine protease inhibitor |

| LMCD1 | Q9NZU5 | LIM and cysteine-rich domains protein 1 | 38.63 | 10 | 1.681 | 1.686 | 2.388 | 2.243 | structural protein |

| TYMS | P04818 | Thymidylate synthase | 19.17 | 4 | 1.675 | 2.752 | 2.151 | 3.228 | methyltransferase |

| ITGA3 | P26006 | Integrin alpha-3 | 21.41 | 19 | 1.671 | 1.729 | 2.847 | 2.944 | receptor, integrin |

| ANLN | Q9NQW6 | Actin-binding protein anillin | 3.91 | 3 | 1.666 | 2.235 | 2.308 | 3.143 | actin binding protein |

| ANXA2 | P07355 | Annexin A2 | 81.42 | 34 | 1.617 | 1.610 | 2.023 | 2.100 | fatty acid metabolic process |

| MACF1 | H3BPE1 | Microtubule-actin cross-linking factor 1, isoforms 1/2/3/5 | 29.64 | 153 | 1.610 | 1.601 | 2.018 | 2.000 | non-motor actin binding protein |

| TPM4 | P67936 | Tropomyosin alpha-4 chain | 48.79 | 8 | 1.534 | 2.126 | 2.878 | 2.893 | actin binding motor protein |

| ACTN4 | K7EJH8 | Alpha-actinin-4 (Fragment) | 68.68 | 1 | 1.526 | 2.411 | 2.251 | 3.153 | non-motor actin binding protein |

| TRIM9 | Q9C026 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase TRIM9 | 4.23 | 3 | 1.508 | 1.143 | 2.077 | 2.109 | ubiquitin-protein ligase |

| LDLR | P01130 | Low-density lipoprotein receptor | 6.63 | 5 | 1.498 | 1.202 | 2.266 | 2.096 | receptor, extracellular matrix glycoprotein |

| SDCBP | O00560 | Syntenin-1 | 28.52 | 4 | 1.495 | 1.490 | 2.581 | 3.361 | membrane trafficking regulatory protein |

| TF | P02787 | Serotransferrin | 45.13 | 27 | 1.422 | 1.526 | 2.224 | 2.216 | transfer/carrier protein |

| TENM2 | H7BYZ1 | Teneurin-2 | 13.86 | 24 | 1.422 | 1.735 | 2.046 | 2.501 | receptor, membrane-bound signaling molecule |

| NES | P48681 | Nestin | 58.61 | 78 | 1.396 | 1.363 | 2.140 | 2.167 | structural protein |

| THY1 | E9PIM6 | Thy-1 membrane glycoprotein (Fragment) | 25.66 | 3 | 1.360 | 1.468 | 2.432 | 2.131 | membrane glycoprotein |

| NEFL | P07196 | Neurofilament light polypeptide | 47.88 | 28 | 1.213 | 1.182 | 2.121 | 2.010 | structural protein |

| CLSTN1 | Q5SR54 | Calsyntenin-1 (Fragment) | 4.35 | 3 | 1.181 | 1.201 | 2.338 | 2.552 | cell adhesion molecule, calcium-binding protein |

| ECI2 | A0A0C4DGA2 | Enoyl-CoA delta isomerase 2, mitochondrial | 40.38 | 11 | 1.148 | 1.262 | 2.239 | 2.894 | transfer/carrier protein, enzyme modulator |

| PTPRE | P23469 | Receptor-type tyrosine-protein phosphatase epsilon | 11.29 | 5 | 0.939 | 2.069 | 3.282 | 3.385 | receptor, protein phosphatase |

| LRRC16A | Q5VZK9 | Leucine-rich repeat-containing protein 16A | 1.90 | 2 | ND | 1.408 | 2.281 | 3.321 | transcription cofactor |

| The 111 Down-Regulated Proteins Expressed Less Than 0.5 Folds (<1% FDR) | |||||||||

| OASL | Q15646 | 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthase-like protein | 12.26 | 4 | 0.127 | 0.393 | 0.215 | ND | nucleotidyltransferase, defense/immunity protein |

| OAS2 | P29728 | 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthase 2 | 9.74 | 9 | 0.151 | 0.158 | 0.115 | 0.068 | nucleotidyltransferase, defense/immunity protein |

| MX1 | P20591 | Interferon-induced GTP-binding protein Mx1 | 56.50 | 28 | 0.164 | 0.177 | 0.150 | 0.130 | microtubule family cytoskeletal protein |

| IFI44L | Q53G44 | Interferon-induced protein 44-like | 39.60 | 13 | 0.179 | 0.206 | 0.189 | 0.191 | immune response |

| IFI44 | Q8TCB0 | Interferon-induced protein 44 | 33.56 | 13 | 0.193 | 0.231 | 0.158 | 0.181 | immune response |

| CASP1 | G3V169 | Caspase | 19.35 | 4 | 0.209 | 0.325 | 0.235 | 0.180 | regulation of apoptotic process |

| BTN3A2 | E9PRR1 | Butyrophilin subfamily 3 member A2 (Fragment) | 27.55 | 2 | 0.220 | 0.555 | 0.261 | 0.360 | ubiquitin-protein ligase |

| INS | C9JNR5 | Insulin (Fragment) | 7.61 | 1 | 0.228 | 0.231 | 0.634 | 0.769 | growth factor |

| MX2 | P20592 | Interferon-induced GTP-binding protein Mx2 | 16.05 | 5 | 0.235 | 0.140 | 0.129 | 0.215 | microtubule family cytoskeletal protein |

| PARP10 | E9PPE7 | Poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 10 | 4.71 | 2 | 0.260 | 0.280 | 0.201 | 0.508 | nucleic acid binding |

| ISG15 | A0A096LNZ9 | Ubiquitin-like protein ISG15 (Fragment) | 50.35 | 6 | 0.273 | 0.293 | 0.253 | 0.264 | ribosomal protein |

| TAP1 | Q03518 | Antigen peptide transporter 1 | 29.08 | 15 | 0.287 | 0.385 | 0.288 | 0.288 | ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter |

| IFIT3 | O14879 | Interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 3 | 48.57 | 18 | 0.288 | 0.301 | 0.261 | 0.258 | RNA binding |

| IFIT2 | P09913 | Interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 2 | 30.08 | 11 | 0.294 | 0.291 | 0.212 | 0.250 | RNA binding |

| IFIT1 | P09914 | Interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1 | 45.82 | 16 | 0.300 | 0.321 | 0.296 | 0.301 | RNA binding |

| KRT10 | P13645 | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 10 | 30.14 | 13 | 0.301 | 0.314 | 0.483 | 0.541 | structural protein |

| DDX58 | O95786 | Probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX58 | 41.73 | 37 | 0.307 | 0.307 | 0.278 | 0.265 | helicase, hydrolase |

| BLOC1S1 | G8JLQ3 | Biogenesis of lysosome-related organelles complex 1 subunit 1 | 50.67 | 3 | 0.308 | 0.461 | 0.296 | 0.417 | transcription factor |

| TRIM21 | P19474 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase TRIM21 | 7.79 | 3 | 0.310 | 0.382 | 0.259 | 0.340 | ubiquitin-protein ligase |

| OAS3 | Q9Y6K5 | 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthase 3 | 30.08 | 29 | 0.316 | 0.306 | 0.246 | 0.237 | nucleotidyltransferase, defense/immunity protein |

| SLC4A4 | Q9Y6R1 | Electrogenic sodium bicarbonate cotransporter 1 | 9.64 | 8 | 0.323 | 0.290 | 0.164 | 0.214 | transporter |

| TAPBP | O15533 | Tapasin | 25.00 | 7 | 0.324 | 0.397 | 0.318 | 0.333 | immunoglobulin receptor superfamily |

| KRT1 | P04264 | Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 1 | 36.49 | 18 | 0.325 | 0.273 | 0.550 | 0.447 | structural protein |

| DTX3L | Q8TDB6 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase DTX3L | 25.81 | 12 | 0.326 | 0.426 | 0.375 | 0.377 | ubiquitin-protein ligase |

| TAP2 | Q03519 | Antigen peptide transporter 2 | 22.16 | 10 | 0.350 | 0.350 | 0.280 | 0.270 | ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter |

| GBP1 | P32455 | Interferon-induced guanylate-binding protein 1 | 28.38 | 13 | 0.362 | 0.346 | 0.296 | 0.202 | heterotrimeric G-protein |

| KRT9 | P35527 | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 9 | 35.47 | 15 | 0.363 | 0.409 | 0.632 | 0.759 | structural protein |

| AGTRAP | Q6RW13 | Type-1 angiotensin II receptor-associated protein | 13.84 | 1 | 0.383 | 0.479 | 0.557 | 0.604 | response to hypoxia |

| PARP9 | Q8IXQ6 | Poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 9 | 16.28 | 12 | 0.387 | 0.392 | 0.395 | 0.359 | nucleic acid binding |

| HLA-B | P30466 | HLA class I histocompatibility antigen, B-18 alpha chain | 57.73 | 1 | 0.396 | 0.414 | 0.307 | 0.344 | immunoglobulin receptor superfamily |

| IRF9 | Q00978 | Interferon regulatory factor 9 | 7.38 | 3 | 0.405 | 0.588 | 0.318 | 0.377 | immune response |

| C19orf66 | Q9NUL5 | UPF0515 protein C19orf66 | 16.15 | 3 | 0.405 | 0.480 | 0.214 | 0.395 | no function identified yet |

| NT5E | P21589 | 5′-nucleotidase | 48.08 | 25 | 0.408 | 0.428 | 0.353 | 0.361 | nucleotide phosphatase |

| STAT1 | P42224 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1-alpha/beta | 53.33 | 36 | 0.408 | 0.422 | 0.369 | 0.381 | transcription factor, nucleic acid binding |

| KRT2 | P35908 | Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 2 epidermal | 7.82 | 3 | 0.411 | 0.329 | 0.428 | 0.471 | structural protein |

| SP100 | P23497 | Nuclear autoantigen Sp-100 | 9.56 | 6 | 0.412 | 0.438 | 0.352 | 0.363 | HMG box transcription factor, signaling molecule |

| B2M | P61769 | Beta-2-microglobulin | 37.82 | 4 | 0.419 | 0.413 | 0.369 | 0.332 | major histocompatibility complex antigen |

| ALB | A0A0C4DGB6 | Serum albumin | 16.89 | 9 | 0.427 | 0.455 | 0.668 | 0.654 | transfer/carrier protein |

| BANF1 | O75531 | Barrier-to-autointegration factor | 34.83 | 2 | 0.429 | 0.467 | 0.308 | 0.408 | DNA binding, DNA integration |

| IFIT5 | Q13325 | Interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 5 | 19.71 | 7 | 0.438 | 0.497 | 0.477 | 0.435 | RNA-binding |

| ERAP2 | Q6P179 | Endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 2 | 6.25 | 5 | 0.461 | 0.527 | 0.371 | 0.457 | metalloprotease |

| HLA-A | P01892 | HLA class I histocompatibility antigen, A-2 alpha chain | 64.38 | 15 | 0.465 | 0.509 | 0.415 | 0.447 | immunoglobulin receptor superfamily |

| NDRG1 | Q92597 | Protein NDRG1 | 27.41 | 6 | 0.468 | 0.541 | 0.260 | 0.246 | stress-responsive protein |

| STAT2 | P52630 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 | 10.93 | 5 | 0.478 | 0.617 | 0.347 | 0.442 | transcription factor, nucleic acid binding |

| HLA-E | P13747 | HLA class I histocompatibility antigen, alpha chain E | 24.02 | 2 | 0.479 | 0.319 | 0.472 | 0.433 | immunoglobulin receptor superfamily |

| ATP6V0C | P27449 | V-type proton ATPase 16 kDa proteolipid subunit | 11.61 | 1 | 0.484 | 0.353 | 0.906 | 0.805 | hydrolase, ATP synthase |

| UCHL3 | P15374 | Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase isozyme L3 | 15.65 | 2 | 0.492 | 0.459 | 0.558 | 0.220 | cysteine protease |

| EPN2 | F6PQP6 | Epsin-2 (Fragment) | 19.56 | 7 | 0.496 | 0.576 | 0.262 | 0.295 | endocytosis |

| DBI | P07108 | Acyl-CoA-binding protein | 65.52 | 6 | 0.501 | 0.502 | 0.263 | 0.148 | transfer/carrier protein |

| SP110 | G5E9C0 | SP110 nuclear body protein, isoform CRA_b | 5.48 | 2 | 0.506 | 0.473 | 0.464 | 0.439 | HMG box transcription factor, signaling molecule |

| TCEAL3 | Q969E4 | Transcription elongation factor A protein-like 3 | 16.50 | 2 | 0.507 | 0.478 | 0.354 | 0.307 | transcription factor |

| LGALS3BP | Q08380 | Galectin-3-binding protein | 39.83 | 19 | 0.507 | 0.533 | 0.427 | 0.457 | receptor, serine protease |

| UBE2L6 | O14933 | Ubiquitin/ISG15-conjugating enzyme E2 L6 | 59.48 | 5 | 0.517 | 0.407 | 0.382 | 0.317 | ligase |

| SMYD2 | Q9NRG4 | N-lysine methyltransferase SMYD2 | 7.39 | 3 | 0.519 | 0.669 | 0.327 | 0.243 | transcription cofactor |

| TREX1 | Q9NSU2 | Three-prime repair exonuclease 1 | 7.86 | 2 | 0.526 | 0.463 | 0.482 | 0.389 | catalytic activityi |

| AK4 | P27144 | Adenylate kinase 4, mitochondrial | 49.33 | 8 | 0.529 | 0.500 | 0.381 | 0.422 | nucleotide kinase |

| FAM96B | J3KS95 | Mitotic spindle-associated MMXD complex subunit MIP18 (Fragment) | 23.58 | 2 | 0.539 | 0.421 | 0.452 | 0.473 | iron-sulfur cluster assembly |

| DPP7 | Q9UHL4 | Dipeptidyl peptidase 2 | 35.37 | 12 | 0.541 | 0.581 | 0.365 | 0.431 | serine protease |

| PML | P29590 | Protein PML | 33.79 | 22 | 0.545 | 0.558 | 0.424 | 0.392 | activator |

| AGA | P20933 | N(4)-(beta-N-acetylglucosaminyl)-l-asparaginase | 24.86 | 5 | 0.551 | 0.635 | 0.415 | 0.490 | protease |

| EPHA2 | P29317 | Ephrin type-A receptor 2 | 19.67 | 15 | 0.555 | 0.523 | 0.386 | 0.395 | nervous system development |

| SERPINI1 | Q99574 | Neuroserpin | 8.78 | 3 | 0.564 | 0.757 | 0.257 | 0.217 | serine protease inhibitor |

| PAPSS2 | O95340 | Bifunctional 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate synthase 2 | 37.30 | 18 | 0.567 | 0.544 | 0.336 | 0.276 | nucleotidyltransferase |

| IDUA | P35475 | Alpha-l-iduronidase | 31.85 | 16 | 0.572 | 0.605 | 0.416 | 0.479 | glycosidase |

| GLA | P06280 | Alpha-galactosidase A | 25.64 | 8 | 0.574 | 0.625 | 0.464 | 0.435 | glycosidase, hydrolase |

| SGSH | P51688 | N-sulphoglucosamine sulphohydrolase | 29.68 | 11 | 0.578 | 0.515 | 0.353 | 0.410 | hydrolase |

| GAA | P10253 | Lysosomal alpha-glucosidase | 24.37 | 19 | 0.584 | 0.657 | 0.426 | 0.461 | glucosidase |

| CHSY3 | Q70JA7 | Chondroitin sulfate synthase 3 | 6.92 | 6 | 0.587 | 0.483 | 0.361 | 0.320 | glycosyltransferase |

| ACP5 | K7EIP0 | Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase type 5 (Fragment) | 36.54 | 1 | 0.587 | 0.544 | 0.313 | 0.246 | glycosylated monomeric metalloprotein enzyme |

| PSMB8 | P28062 | Proteasome subunit beta type-8 | 39.13 | 8 | 0.590 | 0.552 | 0.455 | 0.493 | endopeptidase activity |

| SPTBN2 | O15020 | Spectrin beta chain, non-erythrocytic 2 | 4.35 | 2 | 0.593 | 0.738 | 0.389 | 0.358 | non-motor actin binding protein |

| PGM2L1 | Q6PCE3 | Glucose 1,6-bisphosphate synthase | 48.07 | 30 | 0.598 | 0.627 | 0.492 | 0.448 | glycosyltransferase, mutase |

| SAMD9L | Q8IVG5 | Sterile alpha motif domain-containing protein 9-like | 4.67 | 6 | 0.611 | 0.547 | 0.489 | 0.416 | regulation of protein catabolic process |

| CSTB | P04080 | Cystatin-B | 45.92 | 3 | 0.615 | 0.680 | 0.328 | 0.380 | cysteine protease inhibitor |

| LGMN | Q99538 | Legumain | 10.39 | 4 | 0.618 | 0.636 | 0.483 | 0.499 | cysteine protease |

| CPQ | Q9Y646 | Carboxypeptidase Q | 20.55 | 7 | 0.620 | 0.631 | 0.406 | 0.452 | carboxypeptidase activity |

| CTSA | P10619 | Lysosomal protective protein | 18.75 | 9 | 0.626 | 0.667 | 0.418 | 0.422 | serine protease |

| NAGA | P17050 | Alpha-N-acetylgalactosaminidase | 11.92 | 3 | 0.626 | 0.648 | 0.480 | 0.287 | deacetylase |

| ENO2 | P09104 | Gamma-enolase | 60.83 | 11 | 0.631 | 0.676 | 0.436 | 0.494 | lyase |

| GALNS | P34059 | N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfatase | 8.62 | 5 | 0.633 | 0.687 | 0.436 | 0.377 | hydrolase |

| KCTD12 | Q96CX2 | BTB/POZ domain-containing protein KCTD12 | 33.23 | 11 | 0.634 | 0.624 | 0.446 | 0.480 | enzyme modulator |

| GOLIM4 | O00461 | Golgi integral membrane protein 4 | 18.25 | 11 | 0.638 | 0.671 | 0.391 | 0.416 | transport |

| NMRK1 | B3KN26 | Nicotinamide riboside kinase 1 | 12.26 | 1 | 0.641 | 0.527 | 0.422 | 0.402 | kinase |

| RNASET2 | D6REQ6 | Ribonuclease T2 | 19.27 | 4 | 0.643 | 0.545 | 0.398 | 0.400 | endoribonuclease activity |

| TUBB2B | Q9BVA1 | Tubulin beta-2B chain | 74.16 | 1 | 0.643 | 0.545 | 0.424 | 0.318 | tubulin |

| MTAP | Q13126 | S-methyl-5′-thioadenosine phosphorylase | 71.38 | 15 | 0.645 | 0.683 | 0.484 | 0.492 | phosphorylase |

| NAGLU | P54802 | Alpha-N-acetylglucosaminidase | 26.11 | 13 | 0.646 | 0.706 | 0.466 | 0.478 | glycosidase, hydrolase |

| TXNIP | Q9H3M7 | Thioredoxin-interacting protein | 16.11 | 6 | 0.650 | 0.441 | 0.479 | 0.351 | transcription regulation, oxidative stress mediator |

| BCAR3 | O75815 | Breast cancer anti-estrogen resistance protein 3 | 7.88 | 4 | 0.652 | 0.285 | 0.162 | 0.272 | guanine-nucleotide releasing factor |

| GUSB | P08236 | Beta-glucuronidase | 26.42 | 16 | 0.678 | 0.649 | 0.495 | 0.452 | galactosidase |

| PGK1 | P00558 | Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | 84.41 | 31 | 0.686 | 0.647 | 0.461 | 0.437 | carbohydrate kinase |

| H6PD | O95479 | GDH/6PGL endoplasmic bifunctional protein | 35.65 | 23 | 0.708 | 0.729 | 0.477 | 0.483 | dehydrogenase |

| CSRP1 | P21291 | Cysteine and glycine-rich protein 1 | 64.25 | 9 | 0.711 | 0.670 | 0.426 | 0.427 | actin family cytoskeletal protein |

| CPVL | Q9H3G5 | Probable serine carboxypeptidase CPVL | 21.22 | 9 | 0.711 | 0.640 | 0.480 | 0.453 | serine protease |

| NNMT | P40261 | Nicotinamide N-methyltransferase | 56.06 | 10 | 0.713 | 0.667 | 0.335 | 0.333 | methyltransferase |

| EXTL3 | O43909 | Exostosin-like 3 | 15.34 | 13 | 0.737 | 0.807 | 0.433 | 0.472 | glycosyltransferase |

| VLDLR | P98155 | Very low-density lipoprotein receptor | 8.48 | 6 | 0.738 | 0.699 | 0.460 | 0.478 | receptor, extracellular matrix glycoprotein |

| MMP14 | P50281 | Matrix metalloproteinase-14 | 19.76 | 11 | 0.748 | 0.800 | 0.344 | 0.361 | hydrolase, metalloprotease, protease |

| OSTF1 | Q92882 | Osteoclast-stimulating factor 1 | 53.74 | 9 | 0.750 | 0.649 | 0.459 | 0.463 | signal transduction |

| AKAP2 | Q9Y2D5 | A-kinase anchor protein 2 | 15.83 | 7 | 0.751 | 0.773 | 0.410 | 0.468 | regulation of cell cycle, apoptosis process |

| SIAE | Q9HAT2 | Sialate O-acetylesterase | 12.05 | 5 | 0.769 | 0.725 | 0.346 | 0.294 | esterase |

| MRC2 | Q9UBG0 | C-type mannose receptor 2 | 11.36 | 13 | 0.778 | 0.867 | 0.379 | 0.454 | receptor |

| IDS | P22304 | Iduronate 2-sulfatase | 23.82 | 9 | 0.784 | 0.812 | 0.425 | 0.465 | hydrolase |

| CNTNAP1 | P78357 | Contactin-associated protein 1 | 2.02 | 2 | 0.792 | 0.638 | 0.403 | 0.436 | transporter, membrane-bound signaling molecule, receptor |

| AKR1C3 | S4R3Z2 | Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C3 | 6.67 | 1 | 0.828 | 0.645 | 0.305 | 0.337 | reductase |

| AMDHD2 | Q9Y303 | Putative N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase | 8.07 | 2 | 0.840 | 0.548 | 0.465 | 0.473 | deacetylase |

| MANBA | O00462 | Beta-mannosidase | 6.60 | 3 | 0.901 | 0.799 | 0.356 | 0.482 | galactosidase |

| SH3BP5L | Q7L8J4 | SH3 domain-binding protein 5-like | 5.09 | 2 | 0.912 | 0.931 | 0.354 | 0.411 | protein kinase inhibitor |

| LRP1 | Q07954 | Prolow-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 | 0.62 | 3 | 1.068 | 0.617 | 0.381 | 0.478 | receptor, extracellular matrix glycoprotein |

| ATF7IP | F5GYR7 | Activating transcription factor 7-interacting protein 1 (Fragment) | 9.38 | 1 | ND | 0.447 | 0.441 | 0.146 | transcription regulation |

| VPS29 | Q9UBQ0 | Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 29 | 56.04 | 1 | ND | 0.922 | 0.473 | 0.474 | vesicle coat protein |

a The values of coverage and unique peptides are based on forward labeling result; b Ratios: Spot abundance of tachyplesin I-treated samples relative to the control; 0: control group; 10: 10 μg/mL dose group; 40: 40 μg/mL dose group; forward: forward labeling group; reverse: reverse labeling group; c Functional categories according to Gene ontology and panther biological process annotations.

2.3. Cellular Functions of Differentially Expressed Proteins and Associated Pathways

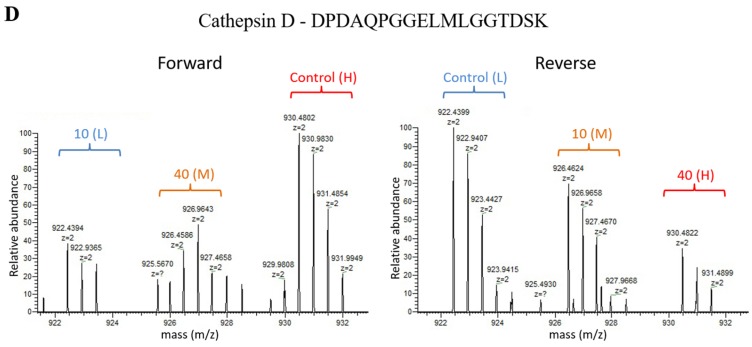

Systematic gene ontology (GO) analysis of 192 differentially expressed proteins identified from both 2D-DIGE and dimethyl labeling proteomic approaches was performed using PANTHER and DAVID tools. Molecular function analysis revealed that the majority of the differentially expressed proteins demonstrated catalytic (42.93%), binding (26.18%) and structural molecule activities (10.99%) (Figure 3A). The biological processes altered by tachyplesin I treatment were most involved in metabolic processes (30.13%), cellular processes (19.88%), developmental processes (8.43%), localization (8.43%) and biological regulation (8.13%) (Figure 3B). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways including lysosome pathway (15 proteins), glycosaminoglycan degradation pathway (6 proteins), antigen processing and presentation pathway (8 proteins), DNA replication pathway (5 proteins), type I diabetes mellitus pathway (4 proteins) and glycolysis/gluconeogenesis pathway (4 proteins) are the top pathways altered in response to tachyplesin I treatment (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Gene ontology analysis of 192 differentially expressed proteins. The significant (p ≤ 0.001) molecular functions (A) and biological processes (B) are presented in the pie chart.

Table 3.

List of altered KEGG pathways with tachyplesin I treatment and their p-values identified by bioinformatic analysis using DAVID (p < 0.1).

| Pathways | p Value | Differentially Expressed Proteins Involved in This Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Lysosome | 1.11 × 10−8 | SGSH, AGA, NAGLU, GUSB, LGMN, ACP5, CTSA, MANBA, ATP6V0C, GLA, IDS, GALNS, NAGA, GAA, IDUA |

| Glycosaminoglycan degradation | 2.53 × 10−5 | SGSH, NAGLU, IDS, GUSB, GALNS, IDUA |

| Antigen processing and presentation | 5.99 × 10−4 | TAP2, LGMN, TAP1, HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-E, TAPBP, B2M |

| DNA replication | 3.51 × 10−3 | MCM7, MCM2, MCM4, MCM5, MCM6 |

| Type I diabetes mellitus | 3.75 × 10−2 | INS, HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-E |

| Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis | 8.93 × 10−2 | TPI1, ENO2, PGK1, ENO1 |

2.4. Tachyplesin I Influences Metabolic Process and Alters the Expressions of Cytoskeleton Proteins

In our study, altered proteins involved in metabolic process occupied major share. Of which, glycolytic/gluconeogenesis enzymes including alpha-enolase (ENO1), gamma-enolase (ENO2), triosephosphate isomerase (TPI1) and phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (PGK1) were found to be down-regulated in response to tachyplesin I treatment. In addition, tachyplesin I treatment on U251 gliomaspheres changed the expression of cytoskeleton proteins. Eighteen out of 192 altered proteins induced by tachyplesin I were classified into cytoskeleton protein class in PANTHER classification system. Several cytoskeleton proteins such as spectrin beta chain, non-erythrocytic 2 (SPTBN2), keratin, type II cytoskeletal 1 (KRT1), keratin, type II cytoskeletal 2 epidermal (KRT2), keratin, type I cytoskeletal 9 (KRT9), keratin, type I cytoskeletal 10 (KRT10), vimentin (VIM), ezrin (EZR), interferon-induced GTP-binding protein Mx1 (MX1), interferon-induced GTP-binding protein Mx2 (MX2), cysteine and glycine-rich protein 1 (CSRP1), elongation factor 1-gamma (EEF1G) and tubulin beta-2B chain (TUBB2B) were down-regulated (Table 2) while neurofilament light polypeptide (NEFL), nestin (NES), kinesin-like protein KIF11 (KIF11), tropomyosin alpha-4 chain (TPM4), dystonin (DST) and LIM and cysteine-rich domains protein 1 (LMCD1) were observed with up-regulation (Table 2). To some extent, all these downstream effects of tachyplesin I contribute to its anti-tumor activity.

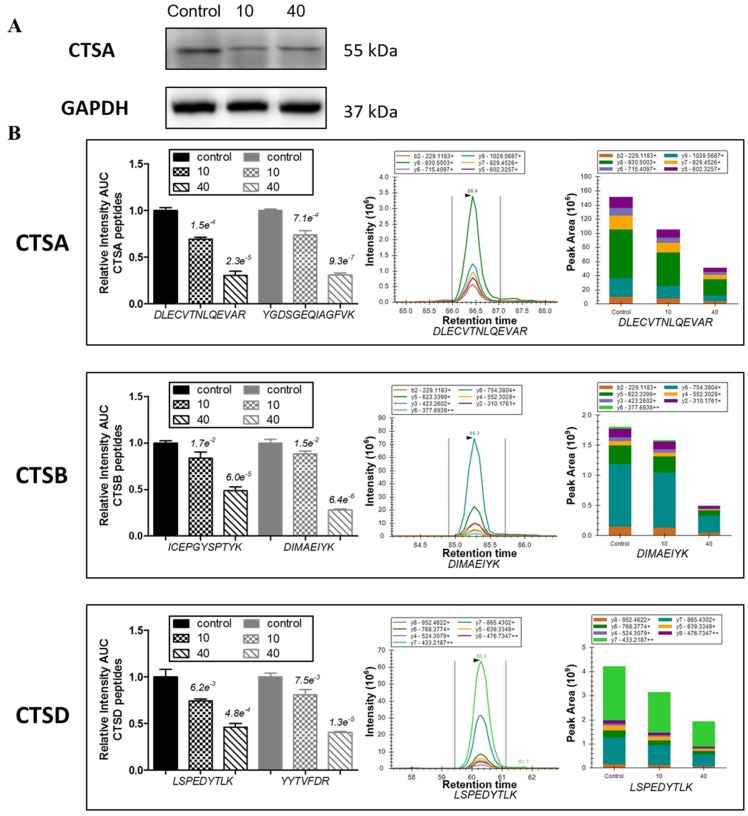

2.5. Tachyplesin I Reduces Expressions of Several Lysosomal Acid Hydrolases

As shown in Figure 4A, consistent with the results of proteomic analysis, protein level of lysosomal protective protein (CTSA) was verified to be down-regulated by tachyplesin I using Western blot. Further, other family members of cathepsins, including cathepsin B (CTSB) and cathepsin D (CTSD), as well as cathepsin A (CTSA) were analyzed by PRM mass spectrometry with three technical replicates. For each protein, two unique peptides were selected and monitored for quantification. The skyline software was used to extract the peak areas (area under the curve, AUC) of six to seven strongest transition ions for each peptide (Supplementary Materials Table S5). The normalized sum AUC of all the transitions for each peptide are showed in Figure 4B, which demonstrates that two unique peptides derived from the same protein have a consistent trend, and variations among different technical replicates are small. The results of PRM analysis showed that tachyplesin I down-regulated the levels of CTSA, CTSB and CTSD, which are consistent with dimethyl labeling results.

Figure 4.

Tachyplesin I reduces expressions of several lysosomal acid hydrolases in U251 gliomaspheres. (A) Expression of cathepsin A (CTSA) was validated by Western blot. GAPDH was used as a loading control; (B) Expressions of CTSA, cathepsin B (CTSB) and cathepsin D (CTSD) were validated by PRM mass spectrometry. The quantification for two peptides per protein in different dose groups is presented.

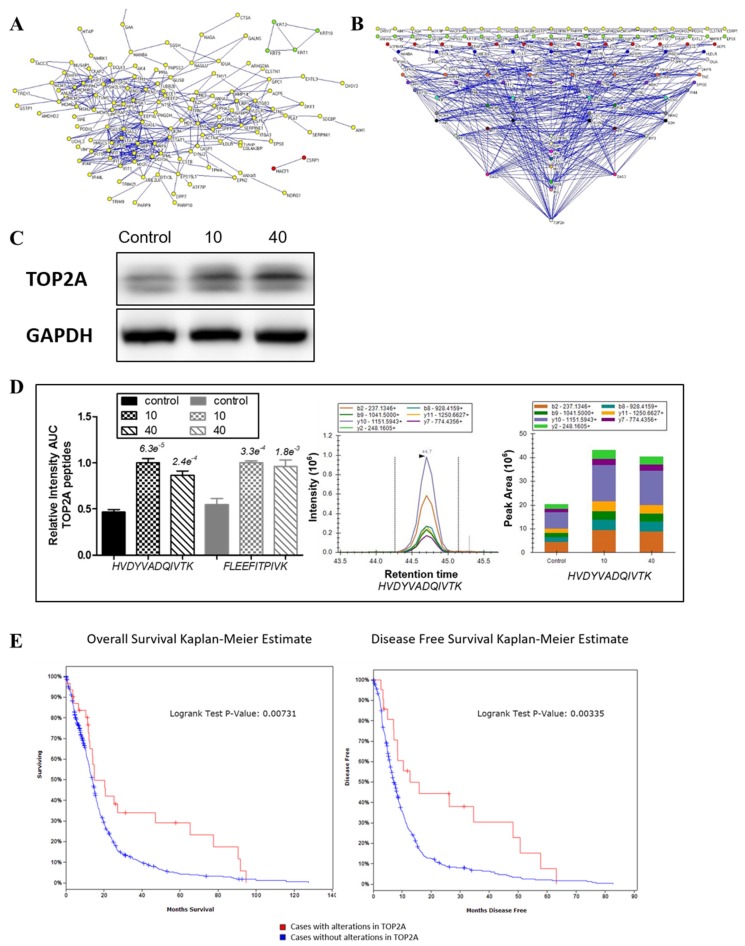

2.6. Protein-Protein Interaction Network of Differentially Expressed Proteins

Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network was established based on the total 192 differentially expressed proteins related to tachyplesin I treatment, including 26 proteins found in 2D-DIGE analysis and 166 proteins found in dimethyl labeling-based LC-MS analysis. Among them, 180 proteins could connect into a network through direct interaction or an intermediate partner at the PPI level (Figure 5A). Interestingly, DNA topoisomerase 2-alpha (TOP2A) seemed to be the crucial protein in the effects of tachyplesin I as it has the most numerous connections and forms the most complex link with other proteins in the signal network (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Role of DNA topoisomerase 2-alpha (TOP2A) in protein–protein interaction (PPI) map of tachyplesin I. (A) The constructed minimum PPI network of tachyplesin I containing 192 differentially expressed proteins found in 2D-DIGE and dimethyl labeling-based LC-MS analysis; (B) Degree distribution map of the proteins in PPI network of tachyplesin I. The proteins are shown as round dots and different colors were only related to degree in the network. TOP2A exhibited to have the biggest degree among all differentially expressed proteins; (C) Expression of TOP2A was validated by Western blot. GAPDH was used as a loading control; (D) Expression of TOP2A was validated by PRM mass spectrometry. The quantification for two peptides per protein in different dose groups is presented; (E) The overall survival (left panel) and the disease-free survival (right panel) of glioma cases with or without alterations in TOP2A. The red curves in the Kaplan–Meier plots includes cases with alterations in TOP2A, the blue curves includes cases without alterations in TOP2A.

2.7. Confirmation of the Involvement of TOP2A in the Effects of Tachyplesin I and Correlation with Clinical Prognosis in TCGA Database

Western blot result (Figure 5C) showed that the expression level of TOP2A was dose-dependent increased after treatment of tachyplesin I, which was consistent with the result of dimethyl labeling based LC-MS/MS analysis (Table 2). At the same time, the expression level of TOP2A was also checked by PRM analysis. As shown in Figure 5D, after tachyplesin I treatment, the expression level of TOP2A was up-regulated, which verified the data obtained from dimethyl labeling based quantification. Then, we used cBioPortal tool to analyze the relationship between the mRNA transcript level of TOP2A and clinical prognosis of GBM patients based on TCGA database to examine the effects of tachyplesin I by targeting on TOP2A. As shown in Figure 5E, patients with alterations in TOP2A at mRNA transcript level have a better prognosis compared with those without alterations in TOP2A. The analysis showed a significantly better overall and disease-free survival of patients with over-expression of TOP2A.

3. Discussion

More and more studies have shown that certain cationic antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), which are toxic to bacteria but not to normal mammalian cells, exhibit a broad spectrum of cytotoxic activity against cancer cells [20]. Tachyplesin I, which is isolated from hemocytes of the horseshoe crab, has been identified as a member of AMPs and exhibits cytotoxic activity against cancer cells. However, it is uncertain why only some types of AMPs get kill cancer cells, while others not. Besides, whether the molecular mechanisms underlying the antitumor and antimicrobial activities are the same or not remains unclear. Through this study we aim to identify the protein targets of tachyplesin I in U251 gliomaspheres by carrying out a large-scale proteome analysis, which can help us to better understand the molecular mechanisms underlying AMPs as potential anti-glioma drugs.

In this study, gel-based 2D-DIGE and stable isotope dimethyl labeling based LC-MS/MS analysis were combined to reveal the alteration in proteome of U251 gliomaspheres treated with tachyplesin I. A total of 192 differentially expressed proteins were identified, most of which are involved in the cellular process of metabolism, especially glycolysis process, and many proteins are localized as cytoskeleton proteins and lysosomal acid hydrolases. Especially, the expression level of some proteins of interest was validated by PRM, a high-resolution method first published in 2012 and had several potential advantages over traditional approach [21]. For example, PRM spectra are highly specific as a result of all the product ions of a peptide are recorded to confirm peptide identity, while traditional MRM analysis can only monitor one transition of a precursor peptide at a time. Moreover, high-resolution of the orbitrap mass analyzer can separate co-eluted background ions, thus increasing selectivity [22].

One of the hallmarks of tumor cells is the preference of glycolysis over oxidative phosphorylation as the main source of energy. Although glycolysis yield less ATP compared to oxidative phosphorylation with the same amount of beginning materials, tumor cells overcome this disadvantage by increasing the up-take of glucose, thus facilitates a higher rate of glycolysis [23]. Studies have showed that glycolysis plays a role in the invasion activity of glioma cells and is becoming a potential drug target [24]. In this study, glycolytic/gluconeogenesis enzymes including alpha-enolase (ENO1), gamma-enolase (ENO2), triosephosphate isomerase (TPI1) and phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (PGK1) were down-regulated in response to tachyplesin I treatment, indicating that tachyplesin I may disrupt the normal energy metabolism process in gliomaspheres through reduced glycolysis, thus contributing to its anti-tumor effect.

Uncontrolled and invasive proliferation is one feature of grade IV glioma, and in order to block and restrain mitotic division, cytoskeleton has been a time-honored target in cancer chemotherapy [25]. In this study, tachyplesin I treatment on U251 gliomaspheres altered the expression of 18 cytoskeleton proteins as classified by PANTHER classification system. Among them, vimentin and ezrin, which are known to be involved in the regulation of metastasis, were down-regulated under the treatment of tachyplesin I, suggesting that cytoskeleton are influenced by tachyplesin I, thus contributes to its anti-tumor activity.

Out of 192 altered proteins, 15 are lysosomal acid hydrolases, including proteases, glycosidases, sulfatases, lipases and so on. In addition, DAVID pathway classification system revealed lysosome as the most significantly altered pathway. More and more experimental evidences suggest that tumor invasion and metastasis are associated with alterations in lysosomes and increased expression of the lysosomal proteases termed cathepsins [26]. In this study, cathepsins consist of cathepsin A, B and D were down-regulated in response to tachyplesin I treatment. Cathepsin A, also called lysosomal protective protein, is a serine carboxypeptidase implicated in autophagy. It induces tumor cell dissemination and a significant increase in cathepsin A activity in lysates of metastatic lesions of malignant tumor was observed compared to primary focus lysates [27]. Cathepsin B is a lysosomal cysteine protease of the papain family of enzymes that function as an endopeptidase and an exopeptidase [28]. Cathepsin D, an aspartic protease resides in membrane of lysosomes, is involved in autophagy and apoptosis pathways [29]. Interestingly, it has been shown that cathepsin B and D play an important role in human glioma progression and invasion [30]. The expression and enzyme activity of cathepsin B and D gradually increased in high-grade glioblastoma. Inhibition of cathepsin B or D activity attenuates extracellular matrix degradation thus reduces migration of glioma cells [31]. Our data showed that the levels of these cathepsins were significantly decreased in tachyplesin I-treated gliomaspheres compared with untreated cells. All those evidences indicate the potential of tachyplesin I as a therapeutic agent for glioma by targeting the lysosomal activity.

In further PPI analysis of differentially expressed proteins, DNA topoisomerase 2-alpha (TOP2A) was shown to be the possible critical target protein of tachyplesin I. TOP2A is a nuclear enzyme for regulation of DNA topology and replication. TOP2A was discovered to be the target of many anti-tumor drugs which had already been widely used in clinic. Previous reports have shown that DNA damage and fragmentation induced by covalent binding of TOP2A to DNA, and forced expression of TOP2A in cells triggered the apoptotic cell death [32,33]. In addition, the TOP2A level has a close relationship with the activity of these anti-tumor drugs and a high level of TOP2A is the foundation of drug susceptibility. Meanwhile, decreased level, altered phosphorylation or mutation of TOP2A could induce the loss of anti-tumor drug target and develop multiple drug resistance (MDR), which has been confirmed in atypical MDR studies with many cell lines [34,35]. Our results showed that there was an increased TOP2A level in U251 gliomaspheres treated with tachyplesin I and it suggest the possible synergistic effect with TOP2A-targeting drugs, combination of which may be more effective on targeted goals and improve chemotherapy effect.

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture and Treatment with Tachyplesin I

U251 human glioma cells were obtained from the Chinese Academy of Sciences Cell Band (Shanghai, China) and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100 units/mL penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The U251 cells in the logarithmic growth phase were thoroughly dissociated to prepare single-cell suspensions. Cell suspensions were washed twice in PBS and resuspended in Neurobasal-A medium with 1× B27 plus 50 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and 50 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (EGF). After 7 days culture, clones of different morphological types were collected. The obtained cells which exhibited certain glioma stem cell phenotypes [11] were cultured as gliomaspheres and passaged every 7 days, based on sphere size.

Tachyplesin I was synthesized by Hanyu Bioengineering Company (Shenzhen, China) with a purity of >95%. Concentrations of tachyplesin I for cell exposure were determined by cell viability assay as described previously [11]. The second generation gliomaspheres were treated with 0, 10, 40 and 80 μg/mL of tachyplesin I for 24 h, and then cells were centrifuged and collected.

4.2. CyDye Minimal Labeling of Protein Samples and 2D-DIGE Electrophoresis

Proteins were extracted from gliomaspheres treated with 0, 10, 40 and 80 μg/mL of tachyplesin I using the lysis buffer containing 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% (w/v) CHAPS and 30 mM Tris-HCl. The concentrations of proteins were determined with the 2-D Quant kit (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then an equal amount (25 μg) of each protein sample was minimally labeled with Cy3 or Cy5 fluorescent dyes (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocols and the internal standard, resulting from pooling equal aliquots of all experimental samples, was labeled with Cy2.

Six differently pooled samples (Table 4), which comprised equal amounts of Cy3- and Cy5-labeled protein samples and Cy2-labeled internal standard, were then separated by first dimension of isoelectric focusing using 24 cm IPG strips (pH 3–11, nonlinear gradient, GE Healthcare), followed by second dimension separation into 12.5% SDS-PAGE gels. Gels were then scanned with different channels for Cy2-, Cy3-, and Cy5-labeled proteins, using a Typhoon Trio Variable Mode Imager (GE Healthcare). The resulting 18 maps were imported into DeCyder 2D v6.5 (GE Healthcare) for statistical analysis. Each gel was separately processed by the Differential In-gel Analysis (DIA) module for spot detection, background subtraction and in-gel normalization before processed by the Biological Variation Analysis (BVA) module for spot matching and intercomparison across the six gels. Student’s t-test was used to analyze the significance of protein spots between two groups, and one way ANOVA was subsequently used to assess the biological significance among all the experimental groups. Statistically significant spots (p < 0.05) with an average ratio ≥1.5 or ≤−1.5 were chosen for protein identification.

Table 4.

Labeling scheme of DIGE for U251 gliomaspheres protein.

| Gel No. | Cy2 | Cy3 | Cy5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gel 01 | Standard | A1 | B2 |

| Gel 02 | Standard | B1 | C3 |

| Gel 03 | Standard | C2 | D3 |

| Gel 04 | Standard | D2 | A2 |

| Gel 05 | Standard | A3 | C1 |

| Gel 06 | Standard | B3 | D1 |

A: control group; B: 10 μg/mL dose group; C: 40 μg/mL dose group; D: 80 μg/mL dose group; 1–3: three biological repeats in each group.

4.3. In-Gel Digestion and Protein Identification by MALDI-TOF/TOF

For identification of spots of interest, a gel was prepared by separating 1 mg of unlabeled proteins pooled from all the samples. The gel was stained by Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 and destained by water to reveal the protein spots. After matching to the analytical DIGE gel, each spot of interest was manually excised from the gel and put into a 1.5 mL tube, followed by thorough decoloration with 50% acetonitrile in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate and dehydration in 100% acetonitrile. Then each gel piece was digested overnight at 37 °C by trypsin in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer. Peptides were extracted from each gel piece, desalted, and identified by an UltrafleXtreme MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA) according to previously described [20].

4.4. Dimethyl Labeling of Protein Samples

Cells were lysed with a lysis buffer containing 4% SDS, 100 mM Tris, pH 8.0 and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Protein concentrations were determined using a Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MS, USA). One milligram protein from each sample was reduced with 5 mM dithiothreitol, alkylated with 15 mM iodoacetamide, and precipitated by methanol and chloroform [36]. The resulting pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer containing 8 M urea, 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.5 and the concentration of urea was diluted to below 2 M before overnight digestion with trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

Dimethyl labeling was performed on-column according to Nature Protocols by Boersema P.J. et al. [37] with minor modifications. Briefly, acidified peptide samples were loaded into SepPak columns (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) after the columns were activated by methanol, 80% acetonitrile in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), and conditioned by 0.1% TFA. After desalting, the samples were labeled separately by passing the columns with CH2O and NaBH3CN (light), CD2O and NaBH3CN (medium) and CD2O and NaBD3CN (heavy) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 20 min at room temperature. Labeling scheme was shown in Table 5. Then the differentially labeled samples were eluted from the columns, mixed and dried by Speedvac (Labconco, Kansas, MO, USA).

Table 5.

Dimethyl-labeling scheme for U251 gliomaspheres protein.

| Samples | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| control group | Heavy (H) | Light (L) |

| 10 μg/mL dose group | Light (L) | Medium (M) |

| 40 μg/mL dose group | Medium (M) | Heavy (H) |

4.5. High pH Fractionation of Peptides and LC-MS/MS Analysis by Obitrap

The dimethyl-labeled sample was resuspended in 1% formic acid (FA), loaded into SepPak column, and fractionated into five fractions by eluting the peptides with 3%, 6%, 9%, 15% and 80% (vol/vol) acetonitrile in 5 mM ammonium formate (pH 10.0), sequentially. After lyophilization in Speedvac, samples were resuspended in 0.1% FA and analyzed by a Q-Exactive orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to an Easy-nLC 1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) ultrahigh pressure liquid chromatography (UHPLC). The LC separation system consisted of a trap column (100 μm i.d. × 4 cm) and an analytical column (75 μm i.d. × 20 cm) both packed with 3 μm/120 Å C18 resins (Dr. Maisch HPLC GmbH, Ammerbuch, Germany). The eluting buffers were 0.1% FA in H2O (buffer A) and 0.1% FA in 99.9% ACN (buffer B). The peptides were first loaded onto the trap column and then separated by the analytical column with 50 min gradient from 7% to 22% buffer B followed by 10 min gradient from 22% to 35% buffer B at a flow rate of 300 nL/min. MS data was acquired in data dependent acquisition (DDA) mode. Survey full scan MS spectra (m/z 350–1550) were acquired in the Orbitrap with resolution of 70,000, target automatic gain control (AGC) value of 3 × 106, and maximum injection time of 100 ms. Dynamic exclusion for scanned presursors was employed for 60 s. After each MS scan, the 10 most intense precursor ions (z ≥ 2) were sequentially isolated and fragmented by higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) using normalized energy 27% with an AGC target of 1 × 105 and a maxima injection time of 50 ms at 17,500 resolution.

Raw data were searched through UniProt Homo sapiens protein database containing 70,076 sequence entries via Sequest HT algorithm with the following parameters: two missed cleavage sites by trypsin, 10 ppm mass tolerance for precursors, 0.02 Da mass tolerance for fragments, and carbamidomethylation (+57.021 Da) of cysteineas static modifications. Moreover, the following dynamic modifications were also set: oxidation of methionine (+15.995 Da), deamidation of asparagine or glutarnine (+0.984 Da), and dimethylation for light-labeled (+28.031 Da) or medium-labeled (+32.056 Da) or heavy-labeled (+36.076 Da) lysine, and N-terminus. All the identified peptides were filtered by FDR <0.01 as reliable identification. Protein Discoverer was used for relative quantification. Differentially expressed proteins were considered for ratios ≤0.5 (down-regulated) and ≥2 (up-regulated).

4.6. Bioinformatic Analysis

The function reports of the candidate proteins whose expression was altered in U251 gliomaspheres due to the effect of tachyplesin I treatment were obtained from the UniProt database (http://www.uniprot.org/) and the protein list of UniProt IDs was input into the PANTHER classification system (http://pantherdb.org/) for GO analysis according to their molecular functions and biological processes. The relevant signaling pathways highly associated with the effect of tachyplesin I treatment on U251 gliomaspheres were identified using DAVID analysis (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/). The protein–protein interaction network of all the differentially expressed proteins was established using String (http://string-db.org/), and then the data was exported as .net file and imported into pajek software for degree based partition of the proteins in the network. The correlation of the possible key proteins involved in the effects of tachyplesin I in our proteomic analysis with its mRNA transcript level and clinical prognosis in GBM patients based on per TCGA data was analyzed by cBioPortal tools (http://www.cbioportal.org/) [38].

4.7. Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM) Mass Spectrometry

We applied PRM to validate the major protein changes observed in the dimethyl labeling analyses. Proteins were extracted from another batch of differently treated U251 gliomaspheres (biological replicate) and digested to peptides. These unlabeled peptides were fractionated and identified as described above with only difference in database searching (no dimethylation as dynamic modifications). For PRM analysis, 2 μg of non-fractionated peptides from each group were separated using the same LC system. Linear gradient ranging from 4% to 35% buffer B over 60 min was used. For each target protein, two unique precursor peptide ions were monitored in the inclusion list. The settings for MS full scan were the same as in the DDA mode with only different in m/z scan range (300–900). The following MS/MS PRM scan parameters were set: orbitrap resolution of 35,000, AGC target value of 5 × 105, auto maximum IT, isolation window of 2 m/z, HCD collision energy of 27, and starting mass of m/z 110. The PRM raw files were analysed using Skyline [39] to extract the peak areas of six to seven most intense transitions for each peptide. Then the data was imported to GraphPad for statistical analysis. Differences between two groups were analyzed by the Student’s t-test and statistical significance was considered when p < 0.05.

4.8. Western Blot Assay

Total proteins were extracted from different groups of U251 gliomaspheres with the same treatment as described in the DIGE analysis, and protein concentrations were quantified by BCA kit. Western blot procedures were carried out as we previously described [40], with minor modifications. Namely, after boiling for 5 min with loading buffer, the same amount of proteins from each groups were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes. The membranes were incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-ECE-1 antibody (sc-376017, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), mouse monoclonal anti-alpha-enolase (sc-101513, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), mouse monoclonal anti-cathepsin A (sc-73766, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH (sc-32233, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) at 1:500 dilution. The immunoblots were developed by incubation with goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (sc-2005, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) as the secondary antibody followed by ECL detection (GE Healthcare).

5. Conclusions

In our study, we combined a gel-based 2D-DIGE approach and a dimethyl labeling LC-MS-based shotgun proteomic strategy to identify the proteome expression alterations in U251 gliomaspheres treated with different doses of tachyplesin I. Our results demonstrate complementary advantages of these two techniques. We show that tachyplesin I alters the cellular metabolism, especially glycolysis process and changes the expression of several cytoskeleton proteins and lysosomal acid hydrolases. Moreover, the important role of DNA topoisomerase 2-alpha (TOP2A) in the signal cascades of tachyplesin I was suggested. Further, parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) mass spectrometry confirmed that the major protein of lysosomal acid hydrolases including cathepsin A, cathepsin B and cathepsin D were down-regulated and the possible target-related protein TOP2A was up-regulated by tachyplesin I treatment. In conclusion, we propose that tachyplesin I may down-regulate cathepsins in lysome and up-regulate TOP2A to inhibit migration and promote apoptosis in glioma, thus contributing to its anti-tumor activity. Further work including functional analyses is needed to elucidate the mode of action of tachyplesin I in tumor cells. As far as we know, there is no previous report that reveals the effect of tachyplesin I on proteome of gliomaspheres and our findings imply that tachyplesin I could serve as a promising candidate in the combined therapy against glioma.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Shenzhen Science and Technology Development Fund Project (No. JCYJ20130331151022276 and GGJS20130331152344401), GDUHTP (2011 and 2013), GDPRSFS (2012), the Project of Guangdong Science and Technology Plan (No. 2014A020217021) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31272474).

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at www.mdpi.com/1660-3397/15/1/20/s1, Table S1: Total identified peptides information in the forward dimethyl labeling experiment, Table S2: Total identified peptides information in the reverse dimethyl labeling experiment, Table S3: Total identified proteins in the forward dimethyl labeling experiment, Table S4: Total identified proteins in the reverse dimethyl labeling experiment, Table S5: Transitions obtained in Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM).

Author Contributions

Gang Jin conceived and designed the experiments; Xuan Li performed the experiments and wrote the paper; Jianguo Dai contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools and revised the manuscript; Yongjun Tang analyzed the data; and Lulu Li cultured the cells.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Alifieris C., Trafalis D.T. Glioblastoma multiforme: Pathogenesis and treatment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015;152:63–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stopschinski B.E., Beier C.P., Beier D. Glioblastoma cancer stem cells—From concept to clinical application. Cancer Lett. 2013;338:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh S.K., Hawkins C., Clarke I.D., Squire J.A., Bayani J., Hide T., Henkelman R.M., Cusimano M.D., Dirks P.B. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature. 2004;432:396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature03128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schonberg D.L., Miller T.E., Wu Q., Flavahan W.A., Das N.K., Hale J.S., Hubert C.G., Mack S.C., Jarrar A.M., Karl R.T., et al. Preferential iron trafficking characterizes glioblastoma stem-like cells. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:441–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pointer K.B., Clark P.A., Zorniak M., Alrfaei B.M., Kuo J.S. Glioblastoma cancer stem cells: Biomarker and therapeutic advances. Neurochem. Int. 2014;71:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bao S., Wu Q., Sathornsumetee S., Hao Y., Li Z., Hjelmeland A.B., Shi Q., McLendon R.E., Bigner D.D., Rich J.N. Stem cell-like glioma cells promote tumor angiogenesis through vascular endothelial growth factor. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7843–7848. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim J.B. Three-dimensional tissue culture models in cancer biology. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2005;15:365–377. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pampaloni F., Reynaud E.G., Stelzer E.H. The third dimension bridges the gap between cell culture and live tissue. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:839–845. doi: 10.1038/nrm2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kong B.H., Park N.R., Shim J.K., Kim B.K., Shin H.J., Lee J.H., Huh Y.M., Lee S.J., Kim S.H., Kim E.H., et al. Isolation of glioma cancer stem cells in relation to histological grades in glioma specimens. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2013;29:217–229. doi: 10.1007/s00381-012-1964-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Q.B., Ji X.Y., Huang Q., Dong J., Zhu Y.D., Lan Q. Differentiation profile of brain tumor stem cells: A comparative study with neural stem cells. Cell Res. 2006;16:909–915. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding H., Jin G., Zhang L., Dai J., Dang J., Han Y. Effects of tachyplesin I on human U251 glioma stem cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015;11:2953–2958. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura T., Furunaka H., Miyata T., Tokunaga F., Muta T., Iwanaga S., Niwa M., Takao T., Shimonishi Y. Tachyplesin, a class of antimicrobial peptide from the hemocytes of the horseshoe crab (Tachypleus tridentatus). Isolation and chemical structure. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:16709–16713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao A.G. Conformation and antimicrobial activity of linear derivatives of tachyplesin lacking disulfide bonds. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999;361:127–134. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y., Xu X., Hong S., Chen J., Liu N., Underhill C.B., Creswell K., Zhang L. RGD-tachyplesin inhibits tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2434–2438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Q.F., Ou-Yang G.L., Peng X.X., Hong S.G. Effects of tachyplesin on the regulation of cell cycle in human hepatocarcinoma SMMC-7721 cells. World J. Gastroenterol. 2003;9:454–458. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i3.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen J., Xu X.M., Underhill C.B., Yang S., Wang L., Chen Y., Hong S., Creswell K., Zhang L. Tachyplesin activates the classic complement pathway to kill tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4614–4622. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ouyang G.L., Li Q.F., Peng X.X., Liu Q.R., Hong S.G. Effects of tachyplesin on proliferation and differentiation of human hepatocellular carcinoma SMMC-7721 cells. World J. Gastroenterol. 2002;8:1053–1058. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i6.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoskin D.W., Ramamoorthy A. Studies on anticancer activities of antimicrobial peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1778:357–375. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baggerman G., Vierstraete E., De Loof A., Schoofs L. Gel-based versus gel-free proteomics: A review. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2005;8:669–677. doi: 10.2174/138620705774962490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang P., Ren X., Huang Z., Yang X., Hong W., Zhang Y., Zhang H., Liu W., Huang H., Huang X., et al. Serum proteomic analysis reveals potential serum biomarkers for occupational medicamentosa-like dermatitis caused by trichloroethylene. Toxicol. Lett. 2014;229:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peterson A.C., Russell J.D., Bailey D.J., Westphall M.S., Coon J.J. Parallel reaction monitoring for high resolution and high mass accuracy quantitative, targeted proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2012;11:1475–1488. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O112.020131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas S.N., Harlan R., Chen J., Aiyetan P., Liu Y., Sokoll L.J., Aebersold R., Chan D.W., Zhang H. Multiplexed targeted mass spectrometry-based assays for the quantification of N-linked glycosite-containing peptides in serum. Anal. Chem. 2015;87:10830–10838. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b02063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ganapathy-Kanniappan S., Geschwind J.F. Tumor glycolysis as a target for cancer therapy: Progress and prospects. Mol. Cancer. 2013;12:152. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramao A., Gimenez M., Laure H.J., Izumi C., Vida R.C., Oba-Shinjo S., Marie S.K., Rosa J.C. Changes in the expression of proteins associated with aerobic glycolysis and cell migration are involved in tumorigenic ability of two glioma cell lines. Proteome Sci. 2012;10:53. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-10-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katsetos C.D., Reginato M.J., Baas P.W., D’Agostino L., Legido A., Tuszyn Ski J.A., Draberova E., Draber P. Emerging microtubule targets in glioma therapy. Semin. Pediatr. Neurol. 2015;22:49–72. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fehrenbacher N., Jaattela M. Lysosomes as targets for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2993–2995. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kozlowski L., Wojtukiewicz M.Z., Ostrowska H. Cathepsin A activity in primary and metastatic human melanocytic tumors. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2000;292:68–71. doi: 10.1007/s004030050012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aggarwal N., Sloane B.F. Cathepsin B: Multiple roles in cancer. Proteom. Clin. Appl. 2014;8:427–437. doi: 10.1002/prca.201300105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicotra G., Castino R., Follo C., Peracchio C., Valente G., Isidoro C. The dilemma: Does tissue expression of cathepsin D reflect tumor malignancy? The question: Does the assay truly mirror cathepsin D mis-function in the tumor? Cancer Biomark. 2010;7:47–64. doi: 10.3233/CBM-2010-0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan G.J., Peng Z.K., Lu J.P., Tang F.Q. Cathepsins mediate tumor metastasis. World J. Biol. Chem. 2013;4:91–101. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v4.i4.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Y., Zhou Y., Zhu K. Inhibition of glioma cell lysosome exocytosis inhibits glioma invasion. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e45910. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vassetzky Y.S., Alghisi G.C., Gasser S.M. DNA topoisomerase II mutations and resistance to anti-tumor drugs. Bioessays. 1995;17:767–774. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McPherson J.P., Goldenberg G.J. Induction of apoptosis by deregulated expression of DNA topoisomerase IIalpha. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4519–4524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McPherson J.P., Brown G.A., Goldenberg G.J. Characterization of a DNA topoisomerase IIalpha gene rearrangement in adriamycin-resistant P388 leukemia: Expression of a fusion messenger RNA transcript encoding topoisomerase iialpha and the retinoic acid receptor alpha locus. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5885–5889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Withoff S., De Jong S., De Vries E.G., Mulder N.H. Human DNA topoisomerase II: Biochemistry and role in chemotherapy resistance (review) Anticancer Res. 1996;16:1867–1880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wessel D., Flugge U.I. A method for the quantitative recovery of protein in dilute solution in the presence of detergents and lipids. Anal. Biochem. 1984;138:141–143. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90782-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boersema P.J., Raijmakers R., Lemeer S., Mohammed S., Heck A.J. Multiplex peptide stable isotope dimethyl labeling for quantitative proteomics. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:484–494. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gao J., Aksoy B.A., Dogrusoz U., Dresdner G., Gross B., Sumer S.O., Sun Y., Jacobsen A., Sinha R., Larsson E., et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cbioportal. Sci. Signal. 2013 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.MacLean B., Tomazela D.M., Shulman N., Chambers M., Finney G.L., Frewen B., Kern R., Tabb D.L., Liebler D.C., MacCoss M.J. Skyline: An open source document editor for creating and analyzing targeted proteomics experiments. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:966–968. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li X., Li X., Zhu Z., Huang P., Zhuang Z., Liu J., Gao W., Liu Y., Huang H. Poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (PARG) silencing suppresses benzo(a)pyrene induced cell transformation. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0151172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.