Abstract

Three-dimensional organization of a gene locus is important for its regulation, as recently demonstrated for the β-globin locus. When actively expressed, the cis-regulatory elements of the β-globin locus are in proximity in the nuclear space, forming a compartment termed the Active Chromatin Hub (ACH). However, it is unknown which proteins are involved in ACH formation. Here, we show that EKLF, an erythroid transcription factor required for adult β-globin gene transcription, is also required for ACH formation. We conclude that transcription factors can play an essential role in the three-dimensional organization of gene loci.

Keywords: EKLF, chromatin, spatial organization, transcription factors, globin, ACH

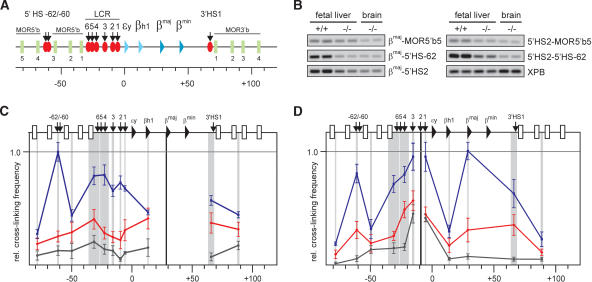

The mouse β-globin locus contains multiple β-like globin genes, arranged from 5′ to 3′ in order of their developmental expression (Fig. 1A). The adult-type βmaj-gene is transcribed at a very low level during primitive erythropoiesis in the embryonic yolk sac, but becomes expressed at high levels around day 11 of gestation (E11) when definitive erythropoiesis commences in the fetal liver (Trimborn et al. 1999). The β-globin locus control region (LCR) is essential for efficient globin transcription (Grosveld et al. 1987; Bender et al. 2000). It consists of a series of DNaseI hypersensitive sites (HS) located ∼50 kb upstream of the βmaj promoter (Fig. 1A). We have shown that the β-globin locus forms an Active Chromatin Hub (ACH) in erythroid cells (Tolhuis et al. 2002). The ACH is a nuclear compartment dedicated to RNA polymerase II transcription, formed by the cis-regulatory elements of the β-globin locus with the intervening DNA looping out. The ACH consists of the HS of the LCR, two HS located ∼60 kb upstream of the embryonic εy-globin gene (5′HS-62/-60) and 3′HS1 downstream of the genes. In addition, the actively expressed globin genes are part of the ACH (Carter et al. 2002; Tolhuis et al. 2002). In erythroid precursors that do not express the globin genes yet, a substructure of the ACH, called a chromatin hub (CH) (Patrinos et al. 2004) is found, which excludes the genes and the HS at the 3′ site of the LCR (Palstra et al. 2003).

Figure 1.

EKLF influences the spatial organization of the β-globin locus. (A) Schematic presentation of the mouse β-globin locus. Globin genes are indicated by triangles: light blue for embryonic and dark blue for the fetal/adult genes. Olfactory receptor genes (MOR5′b and MOR3′b) are indicated by green rectangles and are numbered. DNaseI HS are shown as red ovals with arrows. The scale is in kilobases. (B) Examples of PCR-amplified ligation products run on a 2% agarose gel. Primer combinations are shown on the right. XPB is used to standardize the amount of template (Palstra et al. 2003). (+/+) Wild type; (-/-) EKLF knockout. (C,D) Locus-wide relative cross-linking frequencies in E12.5 fetal livers. Results obtained with wild-type livers are shown in blue, EKLF-/- livers in red, nonexpressing brains in black. The X axis shows position in the locus. Gray shading indicates the positions and sizes of the HindIII fragments containing primers used in the PCR analysis. Black shading represents the position of the fragment containing the fixed primer in the HindIII fragment of the βmaj-gene (C) or 5′HS2 (D). Within each graph, the highest cross-linking frequency value is set to 1. Error bars indicate S.E.M.

Expression of the βmaj-gene requires the presence of the erythroid Krüppel-like transcription factor EKLF, the erythroid-specific member of the Sp/XKLF-family (Miller and Bieker 1993). EKLF-/- mice die of anemia around E14, because of a deficit in β-globin expression (Nuez et al. 1995; Perkins et al. 1995). The β-globin locus contains a number of EKLF-binding sites, in particular in the LCR and the βmaj-globin promoter (Perkins 1999; Bieker 2001). Because βmaj-globin expression depends on the presence of EKLF, we were interested in determining whether EKLF is involved in the formation of the ACH.

Results and Discussion

We used chromatin conformation capture (3C) technology (Dekker et al. 2002) to investigate the three-dimensional conformation of the mouse β-globin locus in the absence of EKLF. Cells from E12.5 EKLF-/- and wild-type fetal livers were cross-linked with formaldehyde, followed by restriction enzyme digestion of the DNA. The samples were ligated under conditions that favor the ligation of DNA fragments that are physically connected through the cross-links. Quantitative PCR across the junctions is used to determine the relative cross-linking frequencies between restriction fragments in the locus. This provides an indication of the nuclear proximity of DNA fragments in vivo (Dekker et al. 2002; Tolhuis et al. 2002; Palstra et al. 2003). Cross-linking frequencies were determined for a total of 66 junctions that can be formed between 12 selected HindIII fragments spread over ∼170 kb of DNA encompassing the β-globin gene cluster (Fig. 1). Examples of quantitative PCR reactions with some of the primer combinations are shown in Figure 1B. An overview of the locus-wide cross-linking frequencies of a restriction fragment that contains the βmaj promoter is shown in Figure 1C. The brain serves as a nonexpressing control tissue (black curve), in which the β-globin locus appears to adopt a linear conformation (Tolhuis et al. 2002). In wild-type E12.5 fetal liver cells, high cross-linking frequencies are found with the LCR and 5′HS-62, indicating their proximity to the βmaj promoter in vivo (blue curve). In the absence of EKLF however, these cross-linking frequencies are much lower and no interaction with a distal site stands out clearly (red curve), showing that the βmaj promoter does not participate stably in a spatial clustering of chromatin. A comparable pattern is observed with locus-wide cross-linking frequencies of a fragment containing 5′HS2 (Fig. 1D). Together with 5′HS3, 5′HS2 is the most prominent transcriptional activating element of the LCR (Ellis et al. 1993, 1996; Fraser et al. 1993; Fiering et al. 1995; Hug et al. 1996). Interactions with 5′HS-62, βmaj, 3′HS1, and the other HS of the LCR are strongly reduced in the absence of EKLF, indicating that 5′HS2 requires the presence of EKLF to participate in the ACH.

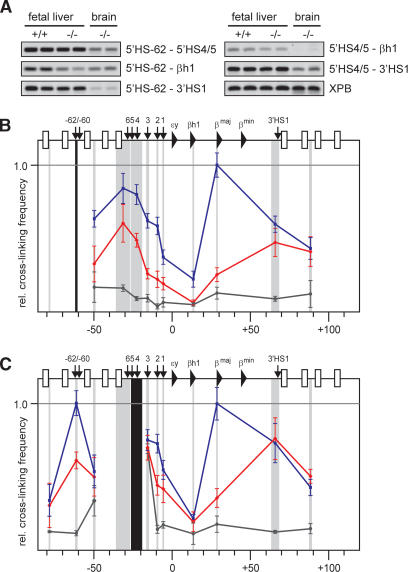

The results shown in Figure 1 demonstrate that the complete ACH is not formed in the absence of EKLF. However, the observed cross-linking frequencies in EKLF-/- fetal liver cells are still higher than those found in nonexpressing brain cells, indicating a different, nonlinear, structure. To investigate this, we compared the locus-wide cross-linking frequencies of restriction fragments containing 5′HS-62 and 5′HS4/5 (Fig. 2). These sites participate in the CH present in erythroid progenitor cells before the globin genes are transcribed (Palstra et al. 2003). Examples of quantitative PCR reactions with some of the primer combinations are shown in Figure 2A. The graphs in Figure 2B show that in wild-type fetal liver cells, 5′HS-62 is in proximity to the LCR, βmaj and 3′HS1. In EKLF-/- fetal liver cells, 5′HS-62 interactions with the HS at the 5′ side of the LCR and with the distal 3′HS1 still stand out, whereas all other cross-linking frequencies are strongly reduced. This indicates the presence of a globin CH, containing 5′HS-62/-60, the HS at the 5′ side of the LCR, and 3′HS1. The same structure is apparent when analyzing locus-wide cross-linking frequencies of a restriction fragment containing 5′HS4/5 at the 5′ side of the LCR (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

An ACH substructure is formed independent of EKLF. (A) Examples of PCR-amplified ligation products run on a 2% agarose gel. Primer combinations are shown on the right. (B,C) Locus-wide relative cross-linking frequencies of HindIII restriction fragments containing 5′HS-62 (b), and 5′HS4/5 (c). See the legend for Figure 1 for other details.

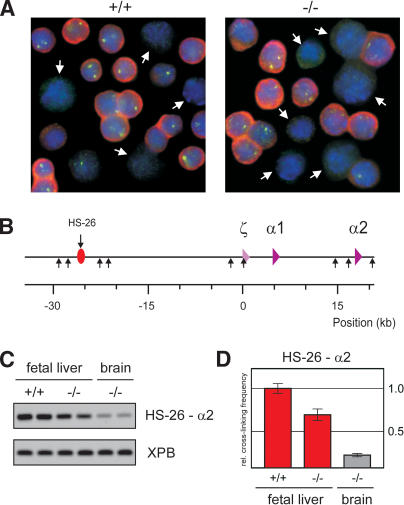

There are remarkable similarities between the structure of the β-globin locus in EKLF-/- fetal liver cells and that observed in I/11 erythroid progenitor cells that do not yet express globin (Palstra et al. 2003; Supplementary Fig. 1). This suggests that EKLF is required for progression from the chromatin hub present in erythroid precursors to a fully active ACH. To investigate whether this β-globin structure in EKLF null cells is a direct consequence of EKLF deficiency or caused by a general differentiation failure, we analyzed expression of the erythroid-specific, but EKLF-independent, α-globin gene locus. Consistent with previous observations, primary transcript in situ hybridization experiments show that α-globin expressing cells are abundantly present in the EKLF-/- fetal liver, demonstrating that in the absence of EKLF cells are progressing to the stage of active globin expression (Fig. 3A) (Nuez et al. 1995; Perkins et al. 1995; Wijgerde et al. 1996; Lim et al. 1997). We do observe that EKLF-/- fetal livers contain ∼20% less α-globin-expressing cells than wild-type fetal livers (∼55% vs. 70% of the total number of cells in the fetal liver). Whereas this may explain the small reduction in cross-linking frequencies observed between some of the β-globin elements, it cannot account for the strongly reduced locus-wide cross-linking frequencies seen with, for example, βmaj and 5′HS2 (Fig. 1C,D). We conclude that the dramatically altered chromatin organisation of the β-globin locus in EKLF null erythroid cells is not due to a general differentiation problem.

Figure 3.

HS-26-promoter interactions in the α-globin locus are not affected by EKLF. (A) In situ hybridization of E12.5 fetal liver cells of wild-type and EKLF-/- fetuses, detecting α-globin mRNA (red) and primary transcripts (green). DAPI staining (blue) is used to show nuclear DNA. White arrows indicate cells that were scored negative for α-globin expression. (B) Schematic drawing of the mouse α-globin locus. The red oval with arrow depicts the position of the HS-26 distal regulatory element. The α-like globin genes are indicated by purple triangles. (Small arrows) HindIII restriction sites. (C) Example of PCR-amplified ligation products of HindIII restriction fragments containing HS-26 and α2 in E12.5 fetal liver and brain cells of wild-type and EKLF-/- fetuses. The XPB PCR product is used as template control. (D) Quantified data of PCR-amplified ligation products. (Red) Fetal liver; (gray) brain. Error bars indicate S.E.M. The cross-linking frequency in wild-type fetal liver cells is set to one.

To substantiate the specificity of the changes in the three-dimensional structure of the β-globin locus in the absence of EKLF, we investigated interactions between the promoter and remote regulatory element of the erythroid-specific, EKLF-independent, α-globin locus. The mouse α-globin locus has two active genes in the fetal liver, α1 and α2, and contains a HS 26 kb upstream of the ζ-globin promoter that is similar to the human α-globin enhancer HS-40 (Fig. 3B; Flint et al. 2001). It is likely that, analogous to the LCR, this element will interact with the α-like globin promoters to enhance expression. The cross-linking frequencies of the restriction fragments containing HS-26 and α2-globin are shown in Figure 3C and D. In wild-type and EKLF-/- fetal liver cells, the cross-linking frequencies are clearly higher than those observed in nonexpressing brain tissue, indicating that HS-26 and the α2-globin gene are in close proximity in both types of erythroid cells. The slightly reduced interaction frequencies observed in EKLF knockout compared with wild-type fetal liver can be explained by the 20% reduction of α-globin expressing cells (see above). We conclude that major alterations in spatial organization are restricted to the EKLF-dependent β-globin locus.

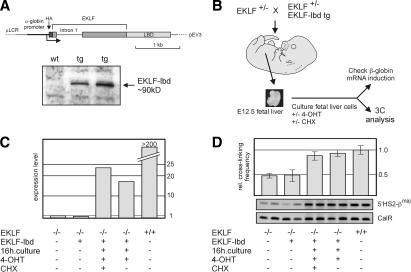

To further investigate whether changes in the spatial organization of the β-globin locus are a direct effect of the activity of EKLF, we wished to induce EKLF activation and simultanously prevent it from activating secondary pathways. For this, we used a fusion between EKLF and a modified estrogen-receptor ligand-binding domain (EKLF–lbd protein), which can be activated by 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (4-OHT) (Littlewood et al. 1995). We wanted to test whether, in an EKLF null background, activated EKLF–lbd protein restores ACH formation in the presence of the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX). In such a setup, genes activated by EKLF cannot be translated into protein, and therefore any structural changes would have to be attributed to EKLF acting directly on the β-globin locus.

Transgenic mice carrying an expression construct of an EKLF–lbd fusion protein were generated. To ensure expression of the fusion protein in EKLF null erythroid cells, we used the erythroid-specific pEV3 expression vector (Needham et al. 1992) and replaced the β-globin promoter with the α-globin promoter. Western blot analysis demonstrates the presence of the HA-tagged EKLF–lbd fusion protein (Fig. 4A). We have previously shown that an EKLF–pEV3 transgene rescues the EKLF null mutation (Tewari et al. 1998). To test whether uninduced EKLF–lbd fusion protein is inactive, we crossed the EKLF–lbd transgenics with the EKLF knockout mice. No EKLF null::EKLF–lbd transgene pups were born. When we dissected the fetuses resulting from this cross at E12.5, we found that the EKLF null::EKLF–lbd transgenic fetuses were indistinguishable from EKLF null fetuses, for example, displaying signs of severe anemia and having very pale fetal livers (data not shown). We conclude that the EKLF–lbd fusion protein is inactive and does not rescue the EKLF null mutation.

Figure 4.

EKLF is directly involved in the spatial organization of the β-globin locus. (A) Schematic drawing of the EKLF–lbd expression construct used to generate transgenic mice. The Western blot shows expression of the EKLF–lbd fusion protein in the fetal livers of transgenic mice detected by an antibody recognizing the HA tag. (B) Flow chart of the experimental design. Fetal livers are isolated from E12.5 control and EKLF null::EKLF–lbd tg fetuses and disrupted, and the erythroid cells are cultured in the presence of 4-OHT with or without CHX for 16 h. Cells are then harvested, cross-linked with formaldehyde, and subjected to 3C analysis. From a portion of the cells, RNA is isolated to check β-globin gene expression. (C) Expression of β-globin analyzed by real-time RT–PCR. Expression of Hprt was used to standardize the β-globin expression levels. Representative experiment is shown. (D) 3C analysis of the interactions between 5′HS2 and the β-globin promoter. Representative examples of the PCR reactions are shown. Error bars indicate S.E.M. Calreticulin was used as template control.

To test the ability of activated EKLF–lbd fusion protein to rescue β-globin gene transcription, we cultured EKLF null::EKLF–lbd fetal liver cells in the presence of 4-OHT (Fig. 4B). After 16 h of culturing, a subset of the cells was used to check for the activation of β-globin gene expression. Real-time RT–PCR analysis of steady-state mRNA levels shows that the β-globin gene is activated in EKLF null::EKLF–lbd cells in the presence of 4-OHT (Fig. 4C). The amount of β-globin transcripts in the tamoxifen-rescued cells is much lower than in wild-type cells, which is is not surprising, as the former cells just start to accumulate β-globin mRNA levels. We conclude that the EKLF–lbd fusion protein can be induced with 4-OHT to activate β-globin gene expression. Moreover, β-globin gene activation by 4-OHT-induced EKLF–lbd also occurs in the presence of CHX (Fig. 4C).

The remaining cells were subjected to 3C analysis using a procedure modified for use with small numbers of cells. Because the amount of material was limiting, we focused on the analysis of interactions between 5′HS2, one of the most prominent activating elements of the LCR, and the promoter of the βmaj gene (Carter et al. 2002; Tolhuis et al. 2002). In untreated EKLF null fetal liver cells, we found similarly low cross-linking frequencies between 5′HS2 and βmaj regardless of the presence of the (uninduced) EKLF–lbd protein (Fig. 4D). In contrast, this interaction is restored in EKLF null::EKLF–lbd cells after culturing for 16 h in the presence of 4-OHT. Importantly, the same effect is also observed when CHX and 4-OHT are present simultaneously (Fig. 4D). These data indicate that ACH interactions are restored in EKLF null::EKLF–lbd cells when the EKLF–lbd fusion protein is activated by 4-OHT. Because this also occurs when protein synthesis is inhibited through the addition of CHX, we conclude that EKLF is directly involved in the completion of ACH formation.

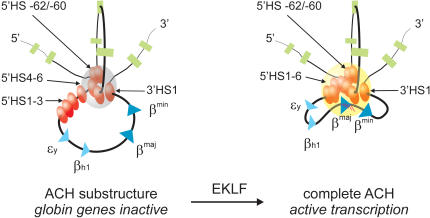

In conclusion, our data show that a chromatin hub is formed independent of EKLF during erythropoiesis, consisting of the 5′HS-62/-60, the HS at the 5′ side of the LCR, and 3′HS1. EKLF is required for the progression to, or stabilization of, a fully functional ACH, which includes the remaining HS of the LCR and the actively transcribed βmaj globin gene (Fig. 5). The βmin gene, which is also expressed in definitive erythroid cells, is known to alternate with the βmaj gene in the ACH in a dynamic flip-flop mechanism (Wijgerde et al. 1995; Trimborn et al. 1999). The EKLF-independent chromatin hub is structurally similar to that present in erythroid precursor cells, which were previously found to already contain EKLF mRNA (Dolznig et al. 2001) and protein (data not shown). This suggests that modifications of the EKLF protein or other protein factors are required to collaborate with EKLF in organizing a fully active β-globin ACH.

Figure 5.

The formation of the complete ACH requires the presence of EKLF. A two-dimensional representation of the proposed three-dimensional structure of the ACH is shown. The ACH is a nuclear compartment dedicated to RNA polymerase II transcription, formed by cis-regulatory elements of the β-globin locus (Palstra et al. 2003). In erythroid cells, a substructure of the ACH, consisting of 5′HS-62/-60, 3′HS1 and HS at the 5′ side of the LCR, is formed independently of EKLF. Progression of this substructure to a fully functional ACH, including the HS at the 3′ side of the LCR and the active β-globin gene, is dependent on the presence of EKLF. (Gray sphere) ACH substructure; (yellow sphere) ACH. RNA transcripts are indicated as red lines. See the legend for Figure 1A for other details.

Recent work has shown that deletion of the promoter of the adult β-globin gene in the human β-globin locus mildly affects ACH formation, suggesting that in addition to the β-globin promoter, other cis-regulatory elements in the human β-globin locus are involved in these interactions (Patrinos et al. 2004). EKLF-binding sites are also present in the LCR, in particular in 5′HS3, and in the 3′ enhancer of the β-globin gene (Wall et al. 1988; Gillemans et al. 1998). Together, these data suggest that the EKLF-dependent interactions of the adult β-globin genes with the ACH involve multiple cis-regulatory elements.

It is also interesting to note that in the EKLF knockout, absence of spatial interactions coincides with loss of chromatin accessibility at 5′HS3 and the βmaj-promoter (Wijgerde et al. 1996; De Laat and Grosveld 2003). We conclude that EKLF is necessary for hypersensitive site formation and the participation of the LCR and the β-globin promoter in the ACH, probably through interactions with a SWI/SNF-related chromatin remodeling complex (Armstrong et al. 1998). Thus, EKLF is the first example of a transcription factor that is required for the proper spatial organization of a mammalian gene locus.

Materials and methods

Chromosome conformation capture

EKLF+/- mice (Nuez et al. 1995) were crossed, and E12.5 fetal livers and brains were isolated. 3C analysis was performed as described (Splinter et al. 2004), with minor adjustments. Individual liver and brain samples were subjected to formaldehyde cross-linking. HindIII restriction enzyme digestion of cross-linked DNA, intramolecular ligation, reversal of cross-links, PCR analysis of ligation products, and calculation of relative cross-linking frequencies was done with 15 pooled wild-type fetal livers, 15 EKLF-/- fetal livers and cells of three pooled EKLF-/- brains. Two independent samples were prepared for the analysis. Each PCR reaction was performed in duplicate and repeated at least three times.

α-Globin

HS-26-α2 promoter cross-linking frequencies were determined with the DNA samples described above and primers recognizing the HindIII restriction fragment containing HS-26 (5′-GAATCTCCATCTCCAAGGG-3′) and the α2 promoter (5′-AAGAGGTGCAGGTGTATTACTG-3′). In situ hybridization of E12.5 fetal liver cells was performed as described before (Van de Corput and Grosveld 2001). Cells were scored positive if α-globin mRNA, primary transcript, or both, was detected. Greater than 300 cells were counted to determine the percentage of α-globin-positive cells in each sample.

Generation of EKLF–lbd transgenic mice

A DNA fragment containing EKLF cDNA and the first intron was linked in frame with the HA tag sequence at the 5′ side and the lbd-coding sequence at the 3′ side. This construct was cloned into the pEV3 vector (Needham et al. 1992) and the β-promoter was replaced by a fragment containing the α-globin promoter. The vector was linearized by AatII, and transgenic mice were generated as described (Kollias et al. 1986).

Culture of primary fetal liver cells

Livers were isolated from E12.5 control and EKLF null::EKLF–lbd tg fetuses. The genotype of the fetuses was confirmed by PCR. Single-cell suspensions of individual fetal livers were cultured for 16h in StemPro-34 containing 1% BSA, 1% glutamine, and 10 U/mL epo, but without serum supplement. The EKLF–lbd was activated by supplementing the medium with either 250 nM 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (4-OHT) alone or with 250 nM 4-OHT and 20 μg/mL cycloheximide (CHX). After 16 h of culture, cells were harvested and a small aliquot was taken for RNA isolation. The 16-h period was chosen because it allowed detection of 4-OHT-induced β-globin gene transcription without CHX causing toxic effects. Fixation of the remainder of the cells with formaldehyde and subsequent isolation of nuclei was performed as described before (Tolhuis et al. 2002).

Preparation of cDNA and Real-time PCR

RNA was isolated using Trizol, according to the manufacturer's guidelines (Invitrogen). The Super-script reverse transcriptase Kit (Invitrogen) was used for preparation of oligo-dT primed cDNA. Expression levels were determined on the Bio-Rad I-Cycler using the qPCR Core kit for Sybr Green 1 (Eurogentec). Expression levels of Hprt were used for normalization of β-globin expression levels.

Primers used were as follows: Hprt-s, AGCCTAAGATGAGCG CAAGT; Hprt-as, ATGGCCACAGGACTAGAACA; β-major-s, ATGC CAAAGTGAAGGCCCAT; β-major-as, CCCAGCACAATCACGATCAT.

Preparation of 3C templates

For the limiting number of cells (∼1.106) obtained from the individual EKLF null::EKLF–lbd tg fetal livers, we adapted the previously described protocol (Tolhuis et al. 2002).

Cross-linked nuclei of E12.5 fetal livers were resuspended in 50 μL of digestion buffer containing 0.1% SDS and incubated for 1 h at 37°C with agitation, Triton X-100 was added to 2.6%, and the nuclei were further incubated for 1 h at 37°C.

The cross-linked chromatin was digested overnight at 37°C with 10 U of HindIII. The restriction enzyme was heat inactivated (25 min at 65°C). After addition of 200 μL of 1.25× ligase buffer and 40 U of T4 ligase, the chromatin was ligated for 4.5 h at 16°C, followed by 30 min at room temperature. Proteinase K was added, and samples were incubated overnight at 65°C to reverse the cross-links. The following day, samples were incubated for 30 min with RNAse, and the DNA was purified by phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation using glycogen as a carrier. Locus-wide cross-linking frequencies of wild-type fetal livers treated with this adapted protocol were similar to those found previously (data not shown).

PCR analysis of the ligation products was performed as described before (Tolhuis et al. 2002; Palstra et al. 2003).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Dutch Organization for Scientific Research NWO (F.G., W.dL. and S.P.), the EU (F.G.) and the Center for Biomedical Genetics (C.B.G.). We thank Ton de Wit for microinjection.

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.317004.

References

- Armstrong J.A., Bieker, J.J., and Emerson, B.M. 1998. A SWI/SNF-related chromatin remodeling complex, E-RC1, is required for tissue-specific transcriptional regulation by EKLF in vitro. Cell 95: 93-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender M.A., Bulger, M., Close, J., and Groudine, M. 2000. β-globin gene switching and DNase I sensitivity of the endogenous β-globin locus in mice do not require the locus control region. Mol. Cell 5: 387-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieker J.J. 2001. Kruppel-like factors: Three fingers in many pies. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 34355-34358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter D., Chakalova, L., Osborne, C.S., Dai, Y.F., and Fraser, P. 2002. Long-range chromatin regulatory interactions in vivo. Nat. Genet. 32: 623-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Laat W. and Grosveld, F. 2003. Spatial organization of gene expression: The Active Chromatin Hub. Chromosome Res. 5: 447-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker J., Rippe, K., Dekker, M., and Kleckner, N. 2002. Capturing chromosome conformation. Science 295: 1306-1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolznig H., Boulme, F., Stangl, K., Deiner, E.M., Mikulits, W., Beug, H., and Mullner, E.W. 2001. Establishment of normal, terminally differentiating mouse erythroid progenitors: Molecular characterization by cDNA arrays. FASEB. J. 15: 1442-1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis J., Talbot, D., Dillon, N., and Grosveld, F. 1993. Synthetic human β-globin 5′HS2 constructs function as locus control regions only in multicopy transgene concatamers. EMBO J. 12: 127-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis J., Tan-Un, K.C., Harper, A., Michalovich, D., Yannoutsos, N., Philipsen, S., and Grosveld, F. 1996. A dominant chromatin-opening activity in 5′ hypersensitive site 3 of the human β-globin locus control region. EMBO J. 15: 562-568. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiering S., Epner, E., Robinson, K., Zhuang, Y., Telling, A., Hu, M., Martin, D.I., Enver, T., Ley, T.J., and Groudine, M. 1995. Targeted deletion of 5′HS2 of the murine β-globin LCR reveals that it is not essential for proper regulation of the β-globin locus. Genes & Dev. 9: 2203-2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint J., Tufarelli, C., Peden, J., Clark, K., Daniels, R.J., Hardison, R., Miller, W., Philipsen, S., Tan-Un, K.C., McMorrow, T., et al. 2001. Comparative genome analysis delimits a chromosomal domain and identifies key regulatory elements in the α globin cluster. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10: 371-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser P., Pruzina, S., Antoniou, M., and Grosveld, F. 1993. Each hypersensitive site of the human β-globin locus control region confers a different developmental pattern of expression on the globin genes. Genes & Dev. 7: 106-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillemans N., Tewari, R., Lindeboom, F., Rottier, R., de Wit, T., Wijgerde, M., Grosveld, F., and Philipsen, S. 1998. Altered DNA-binding specificity mutants of EKLF and Sp1 show that EKLF is an activator of the β-globin locus control region in vivo. Genes & Dev. 12: 2863-2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosveld F., van Assendelft, G.B., Greaves, D.R., and Kollias, G. 1987. Position-independent, high-level expression of the human β-globin gene in transgenic mice. Cell 51: 975-985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hug B.A., Wesselschmidt, R.L., Fiering, S., Bender, M.A., Epner, E., Groudine, M., and Ley, T.J. 1996. Analysis of mice containing a targeted deletion of β-globin locus control region 5′ hypersensitive site 3. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16: 2906-2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollias G., Wrighton, N., Hurst, J., and Grosveld, F. 1986. Regulated expression of human A γ-, β-, and hybrid γ β-globin genes in transgenic mice: Manipulation of the developmental expression patterns. Cell 46: 89-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S.K., Bieker, J.J., Lin, C.S., and Costantini, F. 1997. A shortened life span of EKLF-/- adult erythrocytes, due to a deficiency of β-globin chains, is ameliorated by human γ-globin chains. Blood 90: 1291-1299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlewood T.D., Hancock, D.C., Danielian, P.S., Parker, M.G., and Evan, G.I. 1995. A modified oestrogen receptor ligand-binding domain as an improved switch for the regulation of heterologous proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 23: 1686-1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller I.J. and Bieker, J.J. 1993. A novel, erythroid cell-specific murine transcription factor that binds to the CACCC element and is related to the Kruppel family of nuclear proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13: 2776-2786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needham M., Gooding, C., Hudson, K., Antoniou, M., Grosveld, F., and Hollis, M. 1992. LCR/MEL: A versatile system for high-level expression of heterologous proteins in erythroid cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 20: 997-1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuez B., Michalovich, D., Bygrave, A., Ploemacher, R., and Grosveld, F. 1995. Defective hematopoiesis in fetal liver resulting from inactivation of the EKLF gene. Nature 375: 316-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palstra R.J., Tolhuis, B., Splinter, E., Nijmeijer, R., Grosveld, F., and de Laat, W. 2003. The β-globin nuclear compartment in development and erythroid differentiation. Nat. Genet. 35: 190-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrinos G.P., de Krom, M., de Boer, E., Langeveld, A., Imam, A.M., Strouboulis, J., de Laat, W., and Grosveld, F.G. 2004. Multiple interactions between regulatory regions are required to stabilize an active chromatin hub. Genes & Dev. 18: 1495-1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins A. 1999. Erythroid Kruppel like factor: From fishing expedition to gourmet meal. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 31: 1175-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins A.C., Sharpe, A.H., and Orkin, S.H. 1995. Lethal β-thalassaemia in mice lacking the erythroid CACCC-transcription factor EKLF. Nature 375: 318-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Splinter E., Grosveld, F., and de Laat, W. 2004. 3C technology: Analyzing the spatial organization of genomic loci in vivo. Methods Enzymol. 375: 493-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tewari R., Gillemans, N., Wijgerde, M., Nuez, B., von Lindern, M., Grosveld, F., and Philipsen, S. 1998. Erythroid Kruppel-like factor (EKLF) is active in primitive and definitive erythroid cells and is required for the function of 5′HS3 of the β-globin locus control region. EMBO J. 17: 2334-2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolhuis B., Palstra, R.J., Splinter, E., Grosveld, F., and de Laat, W. 2002. Looping and interaction between hypersensitive sites in the active β-globin locus. Mol. Cell 10: 1453-1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimborn T., Gribnau, J., Grosveld, F., and Fraser, P. 1999. Mechanisms of developmental control of transcription in the murine α- and β-globin loci. Genes & Dev. 13: 112-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Corput M.P. and Grosveld, F.G. 2001. Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of transcript dynamics in cells. Methods 25: 111-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall L., deBoer, E., and Grosveld, F. 1988. The human β-globin gene 3′ enhancer contains multiple binding sites for an erythroid-specific protein. Genes & Dev. 2: 1089-1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijgerde M., Grosveld, F., and Fraser, P. 1995. Transcription complex stability and chromatin dynamics in vivo. Nature 377: 209-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijgerde M., Gribnau, J., Trimborn, T., Nuez, B., Philipsen, S., Grosveld, F., and Fraser, P. 1996. The role of EKLF in human β-globin gene competition. Genes & Dev. 10: 2894-2902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]