Abstract

Despite the large number of leucine-rich-repeat (LRR) receptor-like-kinases (RLKs) in plants and their conceptual relevance in signaling events, functional information is restricted to a few family members. Here we describe the characterization of new LRR-RLK family members as virulence targets of the geminivirus nuclear shuttle protein (NSP). NSP interacts specifically with three LRR-RLKs, NIK1, NIK2, and NIK3, through an 80-amino acid region that encompasses the kinase active site and A-loop. We demonstrate that these NSP-interacting kinases (NIKs) are membrane-localized proteins with biochemical properties of signaling receptors. They behave as authentic kinase proteins that undergo autophosphorylation and can also phosphorylate exogenous substrates. Autophosphorylation occurs via an intermolecular event and oligomerization precedes the activation of the kinase. Binding of NSP to NIK inhibits its kinase activity in vitro, suggesting that NIK is involved in antiviral defense response. In support of this, infectivity assays showed a positive correlation between infection rate and loss of NIK1 and NIK3 function. Our data are consistent with a model in which NSP acts as a virulence factor to suppress NIK-mediated antiviral responses.

Keywords: Receptor-like kinases, nuclear shuttle protein, geminivirus, defense signaling

Receptor-like protein kinases (RLKs) are a diverse group of membrane-spanning proteins with a predicted signal sequence and a cytoplasmic kinase domain that have been implicated in a wide range of signal transduction pathways. The complexity of this family in the plant kingdom may reflect an intensified communication of the plant cell with its environment by perception and transduction of external signals throughout development. In Arabidopsis, whose complete genomic sequence has been determined (The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative 2000), the RLKs make a large gene family comprising 417 family members with receptor configurations (Shiu and Bleecker 2001). These putative transmembrane receptors are structurally organized into a divergent extracellular domain at the N-terminal portion that is thought to confer ligand-binding specificity followed by an internal transmembrane segment and a predicted cytoplasmic signal-transducing domain that includes a juxtamembrane domain, a conserved serine/threonine kinase domain, and a C-terminal region. On the basis of their extracellular domain, these receptors have been organized into different structural classes.

The RLK subfamily with extracytoplasmic leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) represents the largest class of putative receptor-encoding genes in the Arabidopsis genome (Shiu and Bleecker 2001; Dievart and Clark 2004). They are classified into 13 subfamilies (LRR I–XIII) on the basis of the LRR organization, ranging from three to 26 LRRs. Despite their conceptual relevance in cell signaling events, biological function has been assigned to only a few plant LRR-RLKs, in development and in defense responses. Examples of the developmental LRR-RLK genes include the Arabidopsis ERECTA and CLAVATA1 genes that determine floral organ shape and size (Torii et al. 1996; Clark et al. 1997), HAESA that regulates floral abscission (Jinn et al. 2000), SERK1 that is involved in ovule development and early embryogenesis (Hecht et al. 2001), and BRI1 and BAK1 that are involved in brassinosteroid perception and signaling (Li and Chory 1997; Li et al. 2002; Nam and Li 2002). The defense genes are represented by Xa-21 from Oryza sativa, which confers resistance to the bacterial pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae pv. Oryzae (Song et al. 1995) and FLS2 involved in the perception of the bacterial elicitor flagellin (Gomez-Gomez and Boller 2000). Recently, we demonstrated that a nuclear shuttle protein (NSP) from the tomato-infecting geminiviruses TGMV (Tomato golden mosaic virus) and TCrLYV (Tomato crinkle leaf yellows virus) interacts stably with tomato and soybean proteins belonging to the LRR-RLK family and designated as LeNIK (Lycopersicum esculentum NSP-interacting kinase) and GmNIK (glycine max NIK) (Mariano et al. 2004). However, the biological significance of this interaction remains to be elucidated.

Geminiviruses constitute a large group of plant viruses whose genomes are packed as single-stranded DNA circles in small, twinned isometric particles and are converted to double-stranded forms in nuclei of differentiated plant cells (Hanley-Bowdoin et al. 1999). Members of the genus Begomovirus, such as TGMV and TCrLYV, possess two genomic components, DNA-A and DNA-B. The DNA-A has the potential to code for five gene products and is involved in replication, transcriptional activation of viral genes, and encapsidation of the viral genome (Elmer et al. 1988; Kallender et al. 1988; Sunter et al. 1990; Fontes et al. 1992, 1994a; Sunter and Bisaro 1992). The DNA-B component encodes two movement proteins, the nuclear shuttle protein NSP (BV1) and the movement protein MP (BC1), both required for systemic infection (Lazarowitz and Beachy 1999; Gafni and Epel 2002). NSP facilitates the intracellular trafficking of viral DNA between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, whereas MP potentiates its cell-to-cell movement.

Current models of viral cell-to-cell movement hold that the translocation of plant virus into adjacent uninfected cells occurs via plasmodesmata or viral-induced, endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-derived tubules (Lazarowitz and Beachy 1999; Gafni and Epel 2002). From the biochemical activities of MP and NSP from Squash leaf curl virus (SLCV) and Bean dwarf mosaic virus (BDMV), it has been proposed that geminiviruses use both mechanisms for cell-to-cell trafficking of viral DNA (Noueiry et al. 1994; Sanderfoot and Lazarowitz 1996). In the first model, NSP facilitates the intracellular movement of the viral genome from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, where it is replaced by MP that transports the viral DNA to adjacent cells via plasmodesmata (Noueiry et al. 1994). Accordingly, MP from BDMV has been shown to act as a classical movement protein with the capacity to bind viral DNA in vitro, to increase plasmodesmal size exclusion limit, and to promote translocation of the viral genome to adjacent cells in microinjection studies (Noueiry et al. 1994; Rojas et al. 1998). In the second model, MP facilitates NSP-mediated intracellular transport of viral DNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and then mediates the transport of the NSP–DNA complex to adjacent cells via ER-derived tubules induced by the viral infection (Lazarowitz and Beachy 1999). Consistent with this model, MP from the phloem-limited SLCV has been immunolocalized to unique tubules that extend across the walls of developing phloem cells and has been shown to relocate NSP from the nucleus to the cell periphery (Sanderfoot and Lazarowitz 1995; Sanderfoot et al. 1996; Ward et al. 1997). In addition, SLCV MP does not bind DNA in vitro, whereas NSP does (Pascal et al. 1994). The apparent discrepancies between these two models have been explained by the phloem limitation of SLCV, whereas BDMV can also infect nonvascular tissues. However, both models rely on the observations that NSP shuttles viral DNA between the nucleus and the cytoplasm and acts in concert with MP to promote the cell-to-cell spread of viral DNA (Lazarowitz and Beachy 1999; Gafni and Epel 2002).

The localization of NSP and its proposed role in cell-to-cell movement of the viral DNA predict that interactions with host factors may occur in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus. Thus, the interaction of NSP with transmembrane factors could involve an active recognition in the nuclear pore, plasma membrane, or plasmodesmata (Mariano et al. 2004). The recent demonstration that NSP from tomato-infecting geminiviruses associates physically with LRR-RLKs may provide insight into the functions of this complex class of putative transmembrane receptors. In this investigation, we took advantage of the capacity of the geminivirus CaLCuV (Cabbage leaf curl virus) to infect Arabidopsis (Hill et al. 1998). In Arabidopsis, reverse genetic studies are possible (Alonso et al. 2003) to decipher the function of these NSP-interacting putative transmembrane receptors and to determine the biological relevance of the NIK–NSP interaction. We demonstrate that the Arabidopsis NSP-interacting LRR-RLKs are authentic protein kinases with biochemical properties of signaling receptors. Binding of NSP to NIK inhibits its kinase activity, and loss of NIK gene function enhances susceptibility to geminivirus infection. Our data suggest that NIKs are involved in antiviral defenses and that NSP potentially counters the proactivation mechanism of this pathway by inhibiting NIK kinase activity.

Results

NSP interacts with LeNIK- and GmNIK-related proteins from Arabidopsis that belong to the LRRII subfamily of the RLK family

We demonstrated previously that NSP interacts with the kinase domain of a putative transmembrane receptor from tomato (LeNIK) and soybean (GmNIK) (Mariano et al. 2004). The full-length host proteins exhibit a modular organization that resembles members of the Arabidopsis LRRII subfamily of the RLK family (Shiu and Bleecker 2001). Among then, GmNIK is most closely related to At5g16000-encoded product (U19571, 76% sequence identity), followed by At3g25560 (70%) and At1g60800 (61%), whose functions are unknown. The sequence conservation increases to 85% identity if just the kinase domain is used as the basis for comparison. It also shares significant conservation of primary structure with the other members of this family (40%–55% identity). We selected the three GmNIK-most-related LRRII-RLKs to evaluate their capacities to interact with NSP from tomato-infecting geminiviruses (TGMV and TCrYLC) and from an Arabidopsis-infecting geminivirus (CaLCuV). Interactions were assessed by the two-hybrid system monitored for histidine and uracil prototrophy. NSPs interacted with both intact (KD) and nucleotide-binding site (NBS)-deleted kinase (ΔKD) domains of all tested members of the LRRII-RLK subfamily (Table 1). Interactions of two partners were confirmed by monitoring β-galactosidase activity in yeast protein extracts. The NSP interactions were specific to members of the LRRII-RLK subfamily, because NSP did not interact with either an active or an inactive kinase domain of BRI1, a 25 LRR-containing receptor kinase that belongs to the LRR IX subfamily of the RLK family (Shiu and Bleecker 2001; Dievart and Clark 2004) (Fig. 1B). Based on primary sequence conservation as compared with GmNIK and LeNIK, as well as from their capacity to interact with NSP, At5g16000, At3g25560, and At1g60800 are designated here as NIK1, NIK2, and NIK3, respectively. These results validated our previous interpretation that NSP–NIK complex formation was neither virus specific nor host specific (Mariano et al. 2004).

Table 1.

Interaction of NSP from Arabidopsis and tomato-infecting geminiviruses with members of the LRRII-RLK family in yeast

| Bait | pDBLeu

|

pBD-NSPCLCV

|

pBD-NSPTGMV

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prey | +H +U | –H +3AT | –U | β-Gala | +H +U | –H +3AT | –U | β-Gal | +H +U | –H +3AT | –U | β-Gal |

| pAD-KDNIK1 | + | – | – | 0.0 | + | + | + | 0.512 ± | + | + | + | 0.642 ± |

| 0.064 | 0.057 | |||||||||||

| pAD-ΔKDNIK1 | + | – | – | 0.0 | + | + | + | 0.528 ± | + | + | + | 0.505 ± |

| 0.082 | 0.043 | |||||||||||

| pAD-KDNIK2 | + | – | – | 0.0 | + | + | + | 0.425 ± | + | + | + | 0.328 ± |

| 0.037 | 0.091 | |||||||||||

| pAD-KDNIK3 | + | – | – | 0.0 | + | + | + | 0.812 ± | + | + | + | 0.724 ± |

| 0.054 | 0.068 | |||||||||||

| pAD-ΔKDNIK3 | + | – | – | 0.0 | + | + | + | 0.812 ± | + | + | + | 0.799 ± |

| 0.071 | 0.033 | |||||||||||

| pAD-ΔKDSERK1 | + | – | – | 0.0 | + | + | + | 0.215 ± | + | + | + | 0.187 ± |

| 0.027 | 0.076 | |||||||||||

| pAD-SBP | + | – | – | 0.0 | + | – | – | 0.0 | + | – | – | 0.0 |

The bait proteins were expressed as GAL4 DNA-binding domain fusions, and the prey proteins were expressed as GAL4 activation domain fusions in yeast. KD corresponds to the C-terminal kinase domain of the protein and ΔKD is NBS-deleted kinase domain NIK1, NIK2, NIK3, and SERK1 are members of the Arabidopsis LRRII-RLK family. SBP is an unrelated sucrose-binding protein from soybean used as a control in the two-hybrid assays. (U) Uracile; (H) histidine; (3AT) 25 mM 3-aminotriazole; (β-Gal) β-galactosidase activity.

Values for activity are the mean ± standard deviation from four replicas

Figure 1.

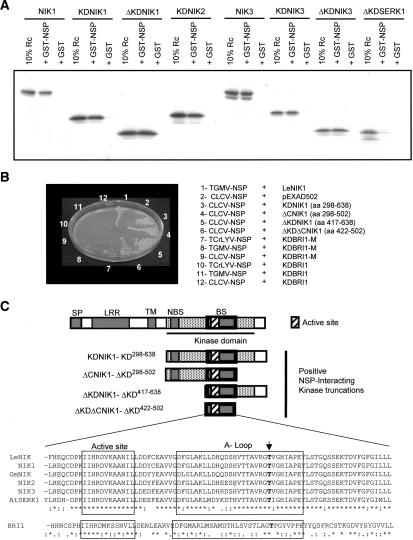

Specificity of NSP interaction with LRR-RLKs. (A) In vitro interaction of NSP with NIKs. In vitro transcribed and translated 35S-labeled proteins, as indicated in the figure, were allowed to interact with bacterially expressed GST or GST-NSP linked to glutathione-Sepharose beads. After extensive washing of the beads, the retained proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized through fluorography. Input contains a sample (10% reaction) of the respective transcription and translation reaction mixtures. (B) NSP does not interact with either active or inactive kinase domain of BRI1, a member of the LRR IX subfamily of the RLK family. Yeast cells expressing the indicated recombinant proteins were plated on selective medium lacking leucine, tryptophan, uracil, and histidine and supplemented with 25 mM 3-AT and grown for 3 d at 30°C. (C) Mapping of NSP-binding domain on NIK1. The diagram represents the NIK1 truncated versions that interacted with NSP (B). In the sequence comparison of the NSP-binding domain among NIKs and AtSERK1- and BRI1-corresponding regions, the active site and A-loop are boxed and the arrow indicates the conserved threonine residue. (SP) Signal peptide; (LRR) leucine-rich repeats; (TM) transmembrane domain; (NBS) nucleotide-binding site; (BS) NSP-binding site.

Specificity of NSP interaction among members of the LRR-RLK family

To further confirm the interaction of NSP with NIKs, we performed an in vitro protein binding assay (Fig. 1A). Purified GST-NSP or GST was incubated with the in vitro translated [35S]Met-labeled intact NIK1 or NIK3, as well as the kinase domain (KD) or the NBS-deleted kinase domain (ΔKD) of NIK1, NIK2, NIK3, and AtSERK1, as indicated in Figure 1A. The resulting complexes were isolated on glutathione-Sepharose beads. Except for ΔKD-SERK1, all the other in vitro labeled proteins, either as intact or truncated kinases, bound to GST-NSP but not to GST alone, indicating that NSP specifically and stably interacts with NIK1, NIK2, and NIK3, but not with AtSERK1 (Fig. 1A). Although the truncated kinase domain of AtSERK1 (ΔKDSERK1) interacted with NSP in yeast, as monitored by His and Ura prototrophy of double-transformed yeast cells, quantification of β-galactosidase activity resulted in a weak signal (0.18 and 0.21 units), whereas NSP interaction with KDNIK1, KDNIK2, and KDNIK3 gave higher values (Table 1). Collectively, these results suggested that NSP discriminates among the members of the LRRII-RLK subfamily. Because NSP interaction with AtSERK1 was weak in yeast and barely detected in vitro, AtSERK1 was not considered further.

To determine the region of NIK1 responsible for specific interaction with NSP, we fused various truncations of its kinase domain to GAL4 activation domain and assayed them for their interaction with NSP in yeast. These results are shown in Figure 1B, and the kinase deletions that scored positively for histidine and uracil prototrophy are schematized in Figure 1C. The deletion analysis mapped the NSP-interacting domain in NIK1 to an 80-amino acid region of the kinase domain (amino acids 422–502) that encompasses the putative active site for Ser/Thr kinases (subdomain VIb–HrDvKssNxLLD) and the activation loop (subdomain VII–DFGAk/rx, plus subdomain VIII–GtxGyiaPEY) (Fig. 1C).

The NIKs are plasma membrane-localized proteins that exhibit biochemical properties consistent with a receptor signaling function

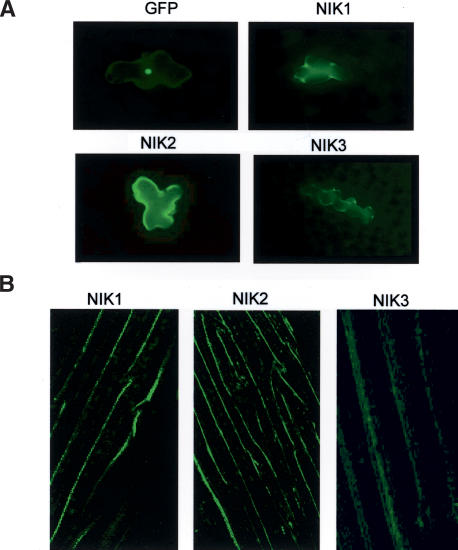

The NSP-interacting LRRII-RLKs possess an internal transmembrane helix and a peptide signal that may target the protein to the secretory apparatus. Consistent with this observation, NIK1 fractionated with leaf microsomal preparations composed primarily of endomembrane vesicles and plasma membranes (data not shown). Furthermore, NIK1, NIK2, and NIK3 fused to green fluorescent protein (GFP) were targeted to the cell surface in transient assays of bombarded young leaves from Arabidopsis (Fig. 2A). Localization of NIK–GFP fusions was also analyzed in cauline cells of stably transformed plants thorough confocal laser scanning microscopy (Fig. 2B). Intense GFP fluorescence was observed in the cell surface delimitating the cell boundaries. Because of the chlorophyll autofluorescent background, chloroplasts were also labeled, although to a lesser extent.

Figure 2.

NIK1, NIK2, and NIK3 are localized to the plasma membrane. (A) Fluorescence deconvolution microscopy images from epidermal cells of Arabidopsis leaves bombarded with GFP, NIK1–GFP, NIK2–GFP, and NIK3–GFP, under the control of the 35S promoter. (B) Confocal fluorescence images of Arabidopsis cauline cells stably transformed with NIK1–GFP, NIK2–GFP, or NIK3–GFP.

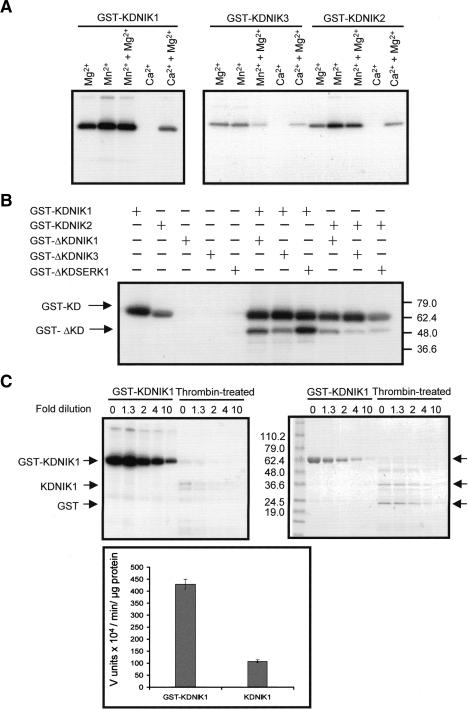

The C-terminal kinase domain of NIKs contains all of the 11 conserved subdomains of protein kinases, in addition to specific signatures of serine/threonine kinases in subdomains V1b and VIII (Hanks et al. 1988; Hanks and Quinn 1991; Taylor et al. 1995). To investigate whether NIKs possess kinase activity, we expressed their C-terminal regions containing an intact kinase domain (KD) or a truncated kinase domain (ΔKD), in which the critical subdomains I and II were deleted, as GST fusions in Escherichia coli and affinity-purified them on glutathione-Sepharose. Kinase activity was assayed in vitro by incubation of purified recombinant proteins with [γ-32P]ATP and analysis of 32P incorporation. As shown in Figure 3A, GST-KDNIK1, GST-KDNIK2, and GST-KDNIK3 undergo autophosphorylation in a Mg2+- or Mn2+-dependent manner and no activity was observed with CaCl2. In fact, inclusion of CaCl2 in Mg2+-based reactions reduced the kinase activity. In contrast, neither GST alone (data not shown) nor the truncated kinase domain fusions (GST-ΔKDNIK1 and GST-ΔKDNIK3) exhibited kinase activity (Fig. 3B). GST-ΔKDSERK1 did not show detectable autophosphorylation, consistent with its lack of the critical Ser/Thr kinase subdomain I and II. These results provide direct biochemical evidence that NIK1, NIK2, and NIK3 cytoplasmic domains possess a functional kinase activity that requires the presence of typical conserved domains for Ser/Thr kinases.

Figure 3.

The NIKs exhibit biochemical properties of signaling receptors. (A) NIKs undergo autophosphorylation in vitro in a Mg2+- or Mn2+-dependent reaction. Bacterially produced GST-fusion proteins (as indicated) were purified and aliquots of 200–500 ng were incubated with [γ-32P]ATP in the presence of the indicated cations. After separation on 4%–20% SDS-PAGE, the phosphoproteins were visualized by autoradiography. (B) Autophosphorylation of NIKs occurs intermolecularly. GST-fusion proteins (as indicated) were incubated with [γ-32P]ATP, separated by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by autoradiography. The migrations of GST-fused kinase domains (GST-KD) and their truncated versions (GST-ΔKD) are indicated. The positions of molecular markers are indicated on the right in kilodaltons. (C) Oligomerization is required for kinase activation. GST-KDNIK1 was cleaved with thrombin and equal amounts of intact or thrombin-cleaved GST-KDNIK1 were used as serial dilutions in the kinase assay. Phosphorylated proteins were analyzed by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE (right) and visualized by autoradiography (left). The migrations of GST-KDNIK and thrombin-cleaved GST-KDNIK1 (GST and KDNIK1) are indicated. Molecular markers are shown in kilodaltons. The plot on the bottom shows the relative kinase activity of GST-KDNIK1 and thrombin-cleaved GST-KDNIK1 expressed as specific activity.

In plants, autophosphorylation of Ser/Thr kinases occurs via either an intra- or intermolecular mechanism (Schulze-Muth et al. 1996; Roe et al. 1997; Sessa et al. 1998; Shah et al. 2001b). To examine the mechanism of NIKs autophosphorylation, we tested the ability of the GST-fused kinase domains (KD) to phosphorylate inactive, truncated versions of transmembrane kinases (ΔKD-NIK1, ΔKD-NIK3, and ΔKD-SERK1). As shown in Figure 3B, GST-KDNIK1 was able to phosphorylate the inactive ΔKD-NIK1 in trans. Transphosphorylation was not restricted to the cognate receptor, as ΔKD-NIK3 and ΔKD-SERK1 were also phosphorylated by NIK1. Likewise, NIK2 (Fig. 3B) and NIK3 (data not shown) could trans-phosphorylate the inactive, truncated kinase domains of the transmembrane receptors. These results indicate that NIK autophosphorylation occurs through an intermolecular mechanism. Furthermore, they suggest that NIKs phosphorylate exogenous substrates, because AtSERK1, which has been shown to be phosphorylated on serine and threonine residues (Shah et al. 2001b), was efficiently phosphorylated by the kinases.

In the mechanism of transphosphorylation-mediated receptor kinase activation, oligomerization precedes the activation of kinase domain (Lemmon and Schlessinger 1994; Roe et al. 1997). To determine whether oligomerization is involved in regulation of NIK1 kinase activity, we took advantage of the capacity of GST to dimerize and the existence of a properly located thrombin-cleavage site on the recombinant protein that allows separation of GST from its fusion partner, KDNIK1. The kinase activity of the thrombin-cleaved GST-KDNIK1 was lower than that of intact GST-KDNIK1 (Fig. 3C, left panel). After normalizing to the amount of protein, the difference was fourfold (Fig. 3C, bottom panel). Progressive dilution of the recombinant protein into the kinase assay had a much greater impact on the specific kinase activity of the thrombin-cleaved GST-KDNIK1 than on that of intact GST-KDNIK1. Thus, in the absence of the GST dimer, the specific activity of the cleaved kinase portion was concentration dependent. These results support a mechanism for activation of the kinase domain involving trans-autophosphorylation mediated by oligomerization of the protein.

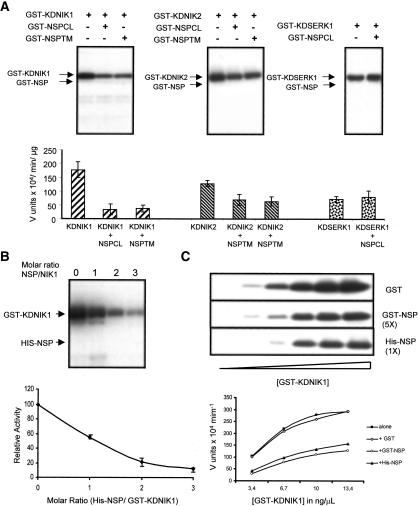

NSP inhibits NIK kinase activity

Given that NIKs are authentic serine/threonine kinase proteins and that SqLCV NSP is phosphorylated in infected plants (Pascal et al. 1994), we next examined whether the viral NSP is an NIK substrate. Neither NIK1 nor NIK2 phosphorylated GST-NSP from TGMV and CaLCuV (Fig. 4A). In contrast, inclusion of the recombinant viral proteins in the kinase assays inhibited both NIK1 and NIK2 activity. Incorporation of 32P into GST-NIK1 and GST-NIK2 was reduced six- and twofold, respectively, by either NSP from CaLCuV or TGMV (Fig. 4A, bottom panel). NSP from TCrLYV inhibited the kinase activity of the NIK1, NIK2, and NIK3 to the same extent as did TGMV-NSP or CaLCuV-NSP (data not shown). Inhibition of NIK activity by GST-fused viral proteins was not due to the presence of the GST domain because His-tagged CaLCuV-NSP, which is not able to dimerize with GST-KDNIK1 via the GST tag, also inhibited the kinase activity of NIK1 (Fig. 4B). A threefold molar excess of His-NSP was sufficient to abolish auto-phosphorylation of NIK1. The inhibitory activity of His-NSP was higher than that of GST-NSP (Fig. 4C) and this difference may be due to conformational constraints imposed by the GST tag.

Figure 4.

NSP inhibits the kinase activity of NIKs. (A) Both TGMV NSP and CaLCuV NSP inhibit NIK1 and NIK2 kinase activity in vitro. GST-KDNIK1 or GST-KDNIK2 were incubated with [γ-32P]ATP and GST-NSP from CaLCuV (GST-NSPCL) or from TGMV (GST-NSPTM). GST-KDSERK1 was incubated with GST-NSPCL. After separation on SDS-PAGE, phosphoproteins were visualized by autoradiography and quantified by phosphoimaging. Relative values of 32P incorporation are the mean of three replicas. (B) Stoi-chiometry of inhibition. Purified GST-KDNIK1 (250 ng) was incubated with [γ-32P]ATP in the presence of increasing amounts of His-NSP. The plot of protein phosphorylation versus molar excess of His-GST was from three replicas. (C) Kinetics of inhibition. Increasing amounts of GST-KDNIK1 were incubated with [γ-32P]ATP in the presence of GST (5 ng/μL), His-NSP (5 ng/μL), or GST-NSP (40 ng/μL). NIK1 phosphorylation was quantified and plotted versus NSP protein concentration.

Despite the strong conservation of the NSP-binding domain among the members of the LRRII-RLK subfamily (Fig. 1C), NSP associated weakly with AtSERK1 (Fig. 1A) and did not inhibit its kinase (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, NSP can be phosphorylated in vitro by reticulocyte kinases (data not shown) and has also been shown to be phosphorylated in vivo (Pascal et al. 1994). Together, these observations suggest that the NSP inhibition of NIK is not due to casual interactions of NSP with kinases, and instead reflects an inherent, specific activity of the viral protein.

NIK1, NIK2, and NIK3 exhibit partially overlapping but distinct expression patterns

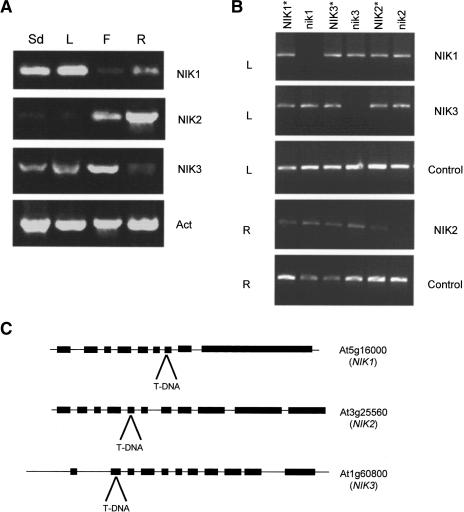

In Arabidopsis, CaLCuV infects leaf tissues with high efficiency, inducing symptoms of severe stunting and leaf epinasty (Hill et al. 1998). To determine whether the onset of geminivirus infection correlates with NIK expression, we analyzed the expression pattern of NIK1, NIK2, and NIK3 by semiquantitative RT–PCR with gene-specific primers (Fig. 5A). All RT–PCRs were repeated with different numbers of cycles to ensure a quantitative linear amplification. In addition, the integrity and amount of cDNA from different organs were routinely assessed with actin-specific primers. Both NIK1 and NIK3 transcripts were highly expressed in seedlings and leaves and accumulated to a lower level in roots. In contrast, NIK2 transcripts predominated in roots and were barely detected in seedlings and leaves. The specificity of the primers was confirmed in expression analysis of T-DNA insertion nik1, nik2, and nik3 alleles (see below) (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

NIKs expression pattern and knockout lines. (A) Organ-specific expression of NIKs. RT–PCR was performed with cDNA prepared from seedlings (Sd), leaves (L), flowers (F), and roots (R) RNA with gene-specific primers, as indicated on the right. (B) Knockout lines for NSP-interacting transmembrane receptors. RT–PCR was performed on leaf (L) and root (R) RNA samples from wild-type (NIK1⋆, NIK2⋆, NIK3⋆), nik1, nik2, and nik3 plants with gene-specific primers, as indicated on the right. The asterisks indicate that the homozygous wild-type alleles were recovered in segregating lines of T-DNA insertion mutants. (C) Annotated NIK genomic loci and diagram of T-DNA insertions. The genes are indicated in the 5′–3′ orientation. Black boxes represent the exons. The position of T-DNA insertion in the null alleles is indicated.

NIK knockout lines exhibit enhanced susceptibility to geminivirus infection

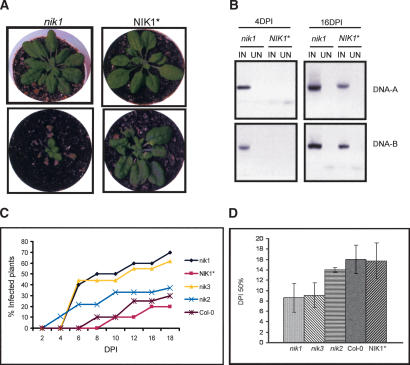

To assess directly the biological significance of NIK–NSP interactions, we identified T-DNA insertion mutants in each gene (Fig. 5C). RT–PCR was performed on leaf (L) and root (R) RNA samples from wild-type (NIK1⋆, NIK2⋆, and NIK3⋆), nik1, nik2, and nik3 knockout (KO) lines. With the gene-specific primers, we detected no accumulation of the corresponding transcript in the respective homozygous T-DNA insertion mutant, confirming that they are null alleles (Fig. 5B). nik1, nik2, and nik3 mutant plants and wild-type Col-0 lines were inoculated with CaLCuV DNA-A and DNA-B. Both Col-0 and nik1-KO lines developed typical CaLCuV symptoms of similar intensity. However, removal of coat protein sequences from CaLCuV DNA-A attenuated the virus in Col-0 plants but not in the nik1 null background (Fig. 6A, bottom panels). In this case, disease symptoms varied in severity from extreme stunting with severe epinasty and chlorosis in nik1-KO to mild stunting with epinasty and moderate chlorosis in Col-0 lines. This attenuated form of the virus was used to analyze the course of infection in the mutant lines. As judged by symptom appearance and viral DNA accumulation, inactivation of NIK1 and NIK3 alleles accelerated the onset of virus infection in comparison to Col-0- and NIK1⋆-infected plants, in which the T-DNA insertion segregated out recovering homozygous NIK1 wild-type alleles (Fig. 6C). The infection rate for nik1 mutant and NIK1⋆ plants correlated with accumulation of viral DNA (Fig. 6B). In addition to being detected earlier in the nik1 mutant, viral DNA-A and DNA-B accumulated to higher levels in these lines compared with NIK1⋆. The enhanced susceptibility phenotype was not observed to the same extent in nik2 null alleles. The infection rate for nik2-KO was slightly higher than that for Col-0 but still considerably less than those for nik1-KO and nik3-KO (Fig. 6B). These results are consistent with the pattern of NIK1, NIK2, and NIK3 expression. In other experiments, the infectivity data, expressed as days postinoculation to get 50% of infected plants (DPI50%), further confirmed the results (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6.

NIK knockout lines exhibit enhanced susceptibility to geminivirus infection. (A) Symptoms associated with CaLCuV infection in knockout lines. Tandemly repeated viral DNA-A and DNA-B were introduced into plants by biolistic inoculation. NIK1⋆ (bottom right) and nik1 (bottom left) infected with CaLCuV at 18 DPI. On the top, NIK1⋆ (right) and nik1 (left) are mock-inoculated plants. (B) Viral DNA accumulation in infected lines. Total DNA was isolated from greenhouse grown NIK1 and nik1 plants at 4 and 16 DPI and subjected to DNA blot analysis with 32P-labeled DNA-A or DNA-B probes, as indicated on the right. (IN) Viral DNA-inoculated plants; (UN) mock-inoculated plants. (C) The onset of infection is accelerated in nik1 and nik3 knockout lines. Ecotype Col-0, nik1, NIK1⋆, nik2, and nik3 lines were infected with CaLCuV DNA by the biolistic method. Values represent the percent of systemically infected plants at different DPI. (D) Infection rates in nik null alleles. The infection rate was expressed as DPI to get 50% of infected plants. Values for DPI50% are the mean ± standard deviation from three replicas.

Discussion

A complete knowledge of the size and complexity of the LRR-RLK family has emerged with the sequence of the Arabidopsis genome but functional information is limited to a few family members that are amenable to genetic approaches. Here we describe the biochemical characterization of new members of this family, identified as virulence targets of the geminivirus NSP. NSP interacted with three members of this family, NIK1, NIK2, and NIK3, which were shown to be authentic Ser/Thr kinases with biochemical properties consistent with a receptor signaling function. NSP inhibited the kinase activity of NIK1, 2, and 3, but not other kinases, suggesting their involvement in antiviral defense response. This interpretation was corroborated in vivo by infectivity assays showing a positive correlation between infection rate and inactivation of NIK1 and NIK3 gene expression. Furthermore, the failure of NIK2 null alleles to exhibit an enhanced susceptibility phenotype strengthened the argument that suppression of NIK-mediated defenses is NSP dependent, because the expression pattern of NIK2 is not spatially coordinated with the onset of CaLCuV infection and, hence, with NSP accumulation.

From primary structural analysis, NIK1, NIK2, and NIK3 are classified as LRR-RLKs and, thus, predicted to be transmembrane serine/threonine receptor kinases. We demonstrated that the NIK proteins exhibit a series of biochemical properties characteristic of authentic Ser/Thr receptor kinases that mediate signal transduction through membranes. First, the NIK proteins were localized to the plasma membrane. Second, we have shown that their cytoplasmic domain is a functional kinase with autophosphorylation properties. Deletion of the conserved Ser/Thr kinase subdomains I and II abolished autophosphorylation of GST-fusion NIK protein, confirming that incorporation of 32P into the fusion protein is due to an intrinsic kinase activity and not to a contaminating protein. Third, the NIK kinase domain was able to phosphorylate exogenous substrates. In fact, we showed that AtSERK1, which has been demonstrated to be phosphorylated on serine/threonine residues (Shah et al. 2001b), is a substrate for NIK. Finally, the molecular features of NIK autophosphorylation described here provided insight into the likely mechanism of NIK receptor action. The phosphorylation of an inactive, deleted-kinase domain by the cognate receptor demonstrated that autophosphorylation occurs via an intermolecular reaction. This transphosphorylation mechanism was further supported by the finding that the autophosphorylation reaction exhibited second-order kinetics (Fig. 4C). Intermolecular autophosphorylation is consistent with a receptor signaling mechanism in which ligand-mediated oligomerization is required for kinase activation. Consistent with this mechanism, removal of the GST tag, which functions as an extra dimerizing component, from the recombinant NIK protein reduced its kinase activity by fourfold. It is likely that oligomerization of NIK precedes activation of the cytoplasmic kinase domain that is mediated by a transphosphorylation event. Dimerization and intermolecular autophosphorylation is a well-documented mechanism for mammalian receptors with tyrosine kinase activity (Lemmon and Schlessinger 1994) and, more recently, has been shown to dictate LRRII-RLK action in plants (Shah et al. 2001a,2001b).

We demonstrated that NSP effectively inhibits autophosphorylation of NIK receptors, suggesting that NSP counters the proactivation mechanism of a NIK-mediated signaling pathway. Accordingly, the NSP-interaction domain was mapped on NIK1 to an 80-amino acid stretch containing the putative active site and the activation loop for Ser/Thr kinases (Fig. 1C). The A-loop plays a critical role in controlling the activity of protein kinases, as well as in substrate recognition (Ellis et al. 1986; Johnson et al. 1996), and its phosphorylation constitutes a key regulatory mechanism that increases the kinase catalytic activity (for reviews, see Johnson et al. 1998; Hubbard and Till 2000). Although the molecular mechanism for NSP inhibition of NIKs remains unsolved, the overlap of the NSP-interacting domain with regulatory domains for kinase activity suggests priorities for structure-based mutagenesis studies on NIK. For example, intermolecular autophosphorylation of a conserved Thr 468 residue in the A-loop of AtSERK1 is required for kinase activation (Shah et al. 2001b). Given the remarkable conservation of this essential threonine in the A-loop of all LRRII-RLKs (Fig. 1C), it is likely that NIKs use a similar regulatory mechanism for kinase activation. It would be interesting to validate experimentally this prediction and to know whether NSP binding to NIK would impair intermolecular phosphorylation of the NIK A-loop and hence kinase activation.

Although we have been unable to detect direct interaction of NIK and NSP in infected plants, as both proteins are expressed at extremely low levels, an in vivo functional link between these proteins has been provided by infectivity assays in loss-of-function mutants. nik1 and nik3 mutant plants displayed enhanced susceptibility phenotypes on geminivirus infection, whereas nik2 mutants were similar to Col-0, with comparable infection rates. These results implicated NIK1 and NIK3 as components of antiviral defenses, whereas NIK2 might not respond as effectively to geminivirus infection. Although we have shown that in vitro NSP-binding activity is a shared property of all three transmembrane receptors, NIK2 expression is barely detected in leaves where the process of infection takes place with high efficiency (Hill et al. 1998). In contrast, NIK1 and NIK3 are highly expressed in leaves, indicating that opportunistically they are capable of eliciting effectively defense strategies against geminivirus infection. Except for NSP that has been demonstrated to target and inhibit these transmembrane kinases specifically, none of the other viral-encoded proteins were found to interact with these transmembrane kinases in yeast (Mariano et al. 2004). Collectively, these results support the argument that the geminivirus NSP acts as virulence factor to suppress NIK-mediated defenses.

Mutant alleles of nik1 and nik3 displayed an enhanced susceptibility phenotype on geminivirus infection, implicating these transmembrane receptors in host defense responses against geminivirus infection. A question that remains unanswered is how NIK-mediated responses act to impair viral infectivity and how NSP interaction would fit in this mechanism. Although NSP–NIK interaction exhibited some properties consistent with the guard hypothesis of plant resistance, our infection results are inconsistent with this possibility (Van der Biezen and Jones 1998). According to the elicitor-receptor model of resistance, NSP would function as a virulence factor by binding to the transmembrane receptor NIK and impairing its interaction with a putative R protein, thereby preventing a resistance response. This model also predicts that in the absence of its putative R protein partner, suppression of NIK expression in these susceptible lines would not affect the efficiency of geminivirus infection. However, both nik1 and nik3 null alleles were isolated in the susceptible Col-0 genetic background and, in contrast to the guard hypothesis for NIK function, they exhibited enhanced infection rates. More likely, the transmembrane receptor NIK functions as an upstream signaling component of an alternative innate antiviral host defense to impact virus replication or movement negatively. Enhanced efficiency of viral DNA replication or cell-to-cell movement in nik1 and nik3 mutants would account for the increased infection rates and viral DNA accumulation in these lines. The action of NSP would potentially counter these NIK-mediated defense responses to geminivirus infection by inhibiting autophosphorylation of NIK and receptor kinase activation. According to this model, NSP binding to the kinase domain of NIK would prevent activation of a NIK-mediated signaling pathway, creating an intracellular environment that is more favorable to virus proliferation and spread.

Recently, the geminivirus TraP (transactivator protein) has been shown to interact with and inactivate adenosine kinase (ADK) and SNF1 kinases (Hao et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2003). Both SNF1 and ADK have been proposed to be components of innate antiviral defenses, and inactivation of these kinases by TraP appears to be a counterdefensive measure. The finding here that NSP also targets and inhibits transmembrane kinases indicates that geminiviruses may effectively adopt a broad-spectrum cellular kinase inhibition-based strategy for countering antiviral defenses. This raises the question as to whether these viral proteins act synergistically to suppress integrated defense pathways or additively to inactivate multiple antiviral defenses. The discovery that NIKs mediate a defense response to geminivirus infection associated with the consequent loss-of-function phenotypes makes the NIK-integrated signaling pathway amenable to genetic characterization. This will complement biochemical approaches to the isolation of interactive proteins and downstream components. These studies also suggest that the NSP–NIK interaction may be a molecular target for the development of a broad-spectrum resistance strategy against geminivirus infection.

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction

The GmNIK and LeNIK cDNA homologs from Arabidopsis, NIK1 (U19571), NIK2 (U21612), NIk3 (U10870), and AtSERK1 (U13033) were obtained from Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center. To create plasmids for the two-hybrid analysis, we amplified the NIK1 C-terminal kinase domain (KD, encoding amino acids 298–638) and its truncated versions (ΔKD298–502, ΔKD417–638, ΔKD422–502, ΔKD502–638) by PCR from U19571 cDNA and cloned them into EcoRI and SstI sites of pEXAD502 (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Inc.), as GAL4 activation domain fusions. Likewise, intact (KD) and truncated versions (ΔKD) of NIK2 (KDNIK2292–635, ΔKDNIK2415–635), NIK3 (KDNIK3257–632, ΔKDNIK3406–632), and AtSERK1 (ΔKDSERK1408–625) kinase domains as well as an active (KDBRI1) and an inactive mutant (KDBRI1-M) kinase domain of BRI1 were fused in-frame to the GAL4 activation domain in pEXAD502. The NSP coding regions were amplified by PCR from TGMV DNA-B (Fontes et al. 1994b), TCrLYV DNA-B (Galvão et al. 2003), or CaLCuV-B (Hill et al. 1998) with Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene) and cloned into SalI and SstI sites of pBDLeu (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Inc.). The resulting clones, pBD-NSPTGMV, pBD-NSPTCrYLC, and pBD-NSPCLCV, contained the GAL4 DNA-binding domain fused to NSP sequences. All the other recombinant plasmids were obtained through the GATEWAY system (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Inc.). Briefly, the specified DNA fragments were amplified by PCR with appropriate extensions and introduced by recombination into the entry vector pDONR201 and then transferred to the appropriate destination vector. A description of the recombinant plasmids is provided below.

GST-fused NSPs and His-tagged NSPs were generated by transferring TGMV NSP, TCrYLV NSP, and CaLCuV NSP coding regions from pDONR201 to the bacterial expression vector pDEST15 (GST fusions) or pDEST17 (His fusions). Likewise, KD and ΔKD sequences (as defined earlier) of NIK1, NIK2, NIK3, and AtSERK1 were introduced into pDONR201 and then transferred to pDEST15, resulting in GST fused to active kinase domains (KD) and to inactive, NBS-deleted kinase domains (ΔKD). For in vitro transcription and translation of proteins, the NIK1, NIK2, NIK3, and AtSERK1 coding regions and their respective KD and ΔKD fragments were transferred from the entry vector to the T7 RNA polymerase-dependent transcription vector pDEST14. NIK1, NIK2, and NIK3 coding regions were also transferred from the entry vector to the binary vector pK7FWG2. The resulting constructs, pK7F–NIK1, pK7F–NIK2, and pK7F–NIK3, contain a GFP gene fused in-frame after the last codon of NIK1, NIK2, and NIK3 cDNAs, respectively, under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter.

Yeast strain and two-hybrid assays

The yeast two-hybrid assays were performed as described previously (Mariano et al. 2004). Yeast reporter strain MaV203 (MAT α, leu2–3,112, trp1–901, his3200, ade2–101, gal4, gal80, SPAL10::URA3, GAL1::lacZ, HIS3UAS GAL1::HIS3@LYS2, can1R, cyh2R) was cotransformed with BD-NSP fusions and pEXAD502 derivatives. Interactions were monitored by the ability of the reporter strain to grow on media lacking leucine, tryptophan, uracil, and histidine but supplemented with 25 mM 3-aminotriazole. The interactions were further confirmed by measuring β-galactosidase activity from yeast extracts with o-nitrophenyl β-D-galactopyranoside, as described previously (Uhrig et al. 1999).

Purification of His-tagged and GST-fusion proteins

All recombinant GST-fused proteins and His-tagged proteins were prepared using the expression vectors pDEST15 (GST fusions) and pDEST17 (6× His fusions) (Invitrogen, Life technologies, Inc.). Plasmids containing different fusions were transformed into E. coli strain BL21 and the synthesis of the recombinant proteins was induced by 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 12 h at 20°C. The GST fusions and His-tagged proteins were affinity-purified using GST-Sepharose beads (Pharmacia) and Ni2+-Agarose (Qiagen), respectively, according to manufacturer's instructions.

In vitro protein binding assay

To express intact and truncated versions of NIK in vitro, we used 1 μg of recombinant plasmid containing the appropriate insert in pDEST14 (as described earlier) in an in vitro transcription and translation system supplemented with [35S]-methionine and T7 RNA polymerase (Promega). The 35S-labeled proteins were incubated for 1 h at 4°C with 50 μL of glutathione-Sepharose beads to which purified GST or GST-NSP had been adsorbed. The beads were pelleted by centrifugation and washed five times with 1 mL of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 120 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Nonidet P-40. Bound proteins were resolved by SDS/PAGE on an 8%–20% polyacrylamide gel and visualized by fluorography.

Fluorescence microscopy

Fluorescence deconvolution microscopy was conducted on a DeltaVision restoration microscope system (Applied Precision) consisting of an Olympus IX70 inverted microscope. Specific filter was used for GFP (490 ± 10 excitation, 510 ± 5 emission) and NIK–GFP patterns were observed in epidermal cells of Arabidopsis leaves bombarded with pK7F–NIK1, pK7F–NIK2, and pK7F–NIK3. For confocal laser scanning microscopy, stably transformed cauline samples were directly examined with a plan Neofluar 40× objective (NA 0.75, Zeiss Corp.) and a LSM 510 microscope system (Carl-Zeiss) equipped with an argon-krypton laser as excitation source (excitation of GFP molecules at 488 nm). GFP emission was detected by using a 505–530-nm filter. Images were assembled with Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems).

Protein kinase assay

Purified GST-KDNIK1, GST-KDNIK2, or GST-KDNIK3 fusion proteins were incubated alone or with GST-ΔKDNIK1, GST-ΔKDNIK3, or GST-ΔKDSERK1 for 30 min at 25°C in 30 μL of kinase buffer containing 18 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MnS04, 1 mM DTT, 10 μM ATP, and 5 μCi [γ-32P]ATP. Phosphoproteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue to verify protein loading, dried, and subjected to autoradiography. Incorporated radioactivity in protein bands was quantified by phosphoimaging.

RT–PCR

Total RNA from seedlings, leaves, flowers, and roots was extracted using an RNAeasy kit (Qiagen). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 2–5 μg of total RNA using the SuperScript III Kit (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR assays were performed with NIK1-, NIK2-, and NIK3-specific primers as described (Cascardo et al. 2000). PCR was also carried out with actin gene-specific primers to assess the quantity and quality of the cDNA.

CaLCuV inoculation and analysis of infected plants

Arabidopsis thaliana plants at the seven-leaf stage were inoculated with plasmids containing partial tandem repeats of CaLCuV DNA-A and DNA-B by biolistic delivery as described (Schaffer et al. 1995). Total nucleic acid was extracted from systemically infected leaves and viral DNA was detected by PCR with DNA-A or DNA-B begomovirus-specific primers (Rojas et al. 1993) and/or by DNA gel blot analysis (Fontes et al. 1994b).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Linda Hanley-Bowdoin for critically reading the manuscript. We thank Dr. Tim Petty for providing the CaLCuV DNA-A and DNA-B, Dr. Gil Sachetto for assistance with confocal microscopy, and ABRC for the T-DNA insertion mutants. This research was supported by the Brazilian Government Agency, CNPq Grant 471606/2003-0 (to E.P.B.F.), a CAPES senior research fellowship (to E.P.B.F.), CNPq graduate fellowships (to A.A.S., D.F.L. and A.J.W.), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the USDA (to J.C.). J.C. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1245904.

References

- Alonso J.M., Stepanova, A.N., Leisse, T.J., Kim, C.J., Chen, H., Shinn, P., Stevenson, D.K., Zimmerman, J., Barajas, P., Cheuk, R., et al. 2003. Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 301: 653-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. 2000. Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 408: 796-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascardo J.C.M., Almeida, R.S., Buzeli, R.A.A., Carolino, S.M.B., Otoni, W.C., and Fontes, E.P.B. 2000. The phosphorylation state and expression of soybean BiP isoforms are differentially regulated following abiotic stresses. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 14494-14500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S.E., Williams, R.W., and Meyerowitz, E.M. 1997. The CLAVATA1 gene encodes a putative receptor kinase that controls shoot and floral meristem size in Arabidopsis. Cell 89: 575-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dievart A. and Clark, S.E. 2004. LRR-containing receptors regulating plant development and defense. Development 131: 251-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis L., Clauser, E., Morgan, D.O., Edery, M., Roth, R.A., and Rutter, W.J. 1986. Replacement of insulin-receptor tyrosine residues 1162 and 1163 compromises insulin-stimulated kinase-activity and uptake of 2-deoxyglucose. Cell 45: 721-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmer J.S., Brand, L., Sunter, G., Gardiner, W., Bisaro, D.M., and Rogers, S.G. 1988. Genetic analysis of the tomato golden mosaic virus. II. The product of the AL1 coding sequence is required for replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 16: 7043-7060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontes E.P.B., Luckow, V.A., and Hanley-Bowdoin, L. 1992. A geminivirus replication protein is a sequence-specific DNA binding protein. Plant Cell 4: 597-608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontes E.P.B., Eagle, P.A., Sipe, P.S., Luckow, V.A,. and Hanley-Bowdoin, L. 1994a. Interaction between a geminivirus replication protein and origin DNA is essential for viral replication. J. Biol. Chem. 269: 8459-8465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontes E.P.B., Gladfelter, H.J., Schaffer, R.L., Petty, I.T.D., and Hanley-Bowdoin, L. 1994b. Geminivirus replication origins have a modular organization. Plant Cell 6: 405-416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gafni Y. and Epel, B.L. 2002. The role of host and viral proteins in intra- and inter-cellular trafficking of geminiviruses. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 60: 231-241. [Google Scholar]

- Galvão R.M., Mariano, A.C., Luz, D.F., Alfenas, P.F., Andrade, E.C., Zerbini, F.M., Almeida, M.R., and Fontes, E.P.B. 2003. A naturally occurring recombinant DNA-A of a typical bipartite begomovirus does not require the cognate DNA-B to infect Nicotiana benthamiana systemically. J. Gen. Virol. 84: 715-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Gomez L. and Boller, T. 2000. FLS2: An LRR receptor-like kinase involved in the perception of the bacterial elicitor flagellin in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cell 5: 1003-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanks S.K. and Quinn, A.M. 1991. Protein kinase catalytic domain sequence database: Identification of conserved features of primary structure and classification of family members. Methods Enzymol. 200: 38-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanks S.K., Quinn, A.M., and Hunter, T. 1988. The protein-kinase family—Conserved features and deduced phylogeny of the catalytic domains. Science 241: 42-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley-Bowdoin L., Settlaga, S.B., Orozco, B.M., Nagar, S., and Robertson, D. 1999. Geminiviruses: Models for plant DNA replication, transcription and cell cycle regulation. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 1: 71-106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao L., Wang, H., Sunter, G., and Bisaro, D.M. 2003. Geminivirus AL2 and L2 proteins interact with and inactivate SNF1 kinase. Plant Cell 15: 1034-1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht V., Vielle-Calzada, J.P., Hartog, M.V., Schmidt, E.D.L., Boutilier, K., Grossniklaus, U, and de Vries, S.C. 2001. The Arabidopsis Somatic Embryogenesis Receptor kinase 1 gene is expressed in developing ovules and embryos and enhances embryogenic competence in culture. Plant Physiol. 127: 803-816. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J.E., Strandberg, J.O., Hiebert, E., and Lazarowitz, S.G. 1998. Asymmetric infectivity of pseudorecombinants of cabbage leaf curl virus and squash leaf curl virus: Implications for bipartite geminivirus evolution and movement. Virology 250: 283-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard S.R. and Till, J.H. 2000. Protein tyrosine kinase structure and function. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69: 373-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinn T.-S., Stone, J.M., and Walker, J.C. 2000. HAESA, an Arabidopsis leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase, controls floral organ abscission. Genes & Dev. 14: 108-117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L.N., Noble, M.E.M., and Owen, D.J. 1996. Active and inactive protein kinases: Structural basis for regulation. Cell 85: 149-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L.N., Lowe, E.D., Noble, M.E.M., and Owen, D.J. 1998. The structural basis for substrate recognition and control by protein kinases. FEBS Lett. 430: 1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallender H., Petty, I.T.D., Stein, V.E., Panico, M., Blench, I.P., Etienne, A.T., Morris, H.R., Coutts, R.H.A., and Buck, K.W. 1988. Identification of the coat protein of Tomato Golden Mosaic Virus. J. Gen. Virol. 69: 1351-1357. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarowitz S.G. and Beachy, R.N. 1999. Viral movement proteins as probes for intracellular and intercellular trafficking in plants. Plant Cell 11: 535-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon M.A. and Schlessinger, J. 1994. Regulation of signal-transduction and signal diversity by receptor oligomerization. Trends Biochem. Sci. 19: 459-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. and Chory, J. 1997. A putative leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase involved in brassinosteroid signal transduction. Cell 90: 929-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Wen, J., Lease, K.A., Doke, J.T., Tax, F.E., and Walker, J.C. 2002. BAK1, an Arabidopsis LRR receptor-like protein kinase, interacts with BRI1 and modulates brassinosteroid signaling. Cell 110: 213-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariano A.C., Andrade, M.O., Santos, A.A., Carolino, S.M.B., Oliveira, M.L., Baracat-Pereira, M.C., Brommonshenkel S.H., and Fontes, E.P.B. 2004. Identification of a novel receptor-like protein kinase that interacts with a geminivirus nuclear shuttle protein. Virology 318: 24-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam K.H. and Li, J. 2002. BRI1/BAK1, a receptor kinase pair mediating brassinosteroid signaling. Cell 110: 203-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noueiry A.D., Lucas, W.J., and Gilbertson, R.L. 1994. Two proteins of a plant DNA virus coordinate nuclear and plasmodesmal transport. Cell 76: 925-932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascal E., Sanderfoot, A.A., Ward, B.M., Medville, R., Turgeon R., and Lazarowitz, S.G. 1994. The geminivírus BR1 movement protein binds single-stranded DNA and localizes to the cell nucleus. Plant Cell 6: 995-1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe J.L., Durfee, T., Zupan, J.R., Repetti, P.P., McLean, B.G., and Zambryski, P.C. 1997. TOUSLED is a nuclear serine/threonine protein kinase that requires a coiled-coil region for oligomerization and catalytic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 5838-5845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas M.R., Gilbertson, R.L., Russel, D.R., and Maxwell, D.P. 1993. Use of degenerate primers in the polymerase chain reaction to detect whitefly-transmitted geminiviruses. Plant Dis. 77: 340-347. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas M.R., Noueiry, A.O., Lucas, W.J., and Gilbertson, R.L. 1998. Bean dwarf mosaic geminivirus movement proteins recognize DNA in a form- and size-specific manner. Cell 95: 105-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderfoot A.A. and Lazarowitz, S.G. 1995. Cooperation in viral movement—The geminivirus BL1 movement protein interacts with BR1 and redirects it from the nucleus to the cell periphery. Plant Cell 7: 1185-1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ____. 1996. Getting it together in plant virus movement: Co-operative interactions between bipartite geminivirus movement proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 6: 353-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderfoot A.A., Ingham, D.J., and Lazarowitsz, S.G. 1996. A viral movement protein as a nuclear shuttle. The geminivirus BR1 movement protein contains domains essential for interaction with BL1 and nuclear localization. Plant Physiol. 110: 23-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer R.L., Miller, C.G., and Petty, I.T.D. 1995. Virus and host-specific adaptations in the BL1 and BR1 genes of bipartite geminiviruses. Virology 214: 330-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze-Muth P., Irmler, S., Schröder, G., and Schröder, J. 1996. Novel type of receptor-like protein kinase from a higher plant (Catharanthus roseus): cDNA, gene, intramolecular autophosphorylation, and identification of a threonine important for auto- and substrate phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 25: 26684-26689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessa G., D'Ascenzo, M., Loh, Y.-T., and Martin, G.B. 1998. Biochemical properties of two protein kinases involved in disease resistance signaling in tomato. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 15860-15865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah K., Gadella Jr., T.W., van Erp, H., Hecht, V., and de Vries, S.C. 2001a. Subcellular localization and oligomerization of the Arabidopsis thaliana somatic embryogenesis receptor kinase 1 protein. J. Mol. Biol. 309: 641-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah K., Vervoort, J., and de Vries, S.C. 2001b. Role of threonines in the Arabidopsis thaliana somatic embryogenesis receptor kinase 1 activation loop in phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem 276: 41263-41269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiu S.H. and Bleecker, A.B. 2001. Receptor-like kinases from Arabidopsis form a monophyletic gene family related to animal receptor kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 10763-10768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W.-Y., Wang, G.-L., Chen, L.-L., Kim, H.-S., Pi, L.-Y., Holsten, T., Gardner, J., Wang, B., Zhal, W.-X., Zhu, L.-H., et al. 1995. A receptor-like protein encoded by the rice disease resistance gene, Xa21. Science 270: 1804-1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunter G. and Bisaro, D.M. 1992. Transactivation of geminivirus AR1 and BR1 gene expression by the viral AL2 gene product occurs at the level of transcription. Plant Cell 4: 1321-1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunter G., Hartitz, M.D., Hormudzi, S.G., Brough, C.L., and Bisaro, D.M. 1990. Genetic analysis of tomato golden mosaic virus: ORF AL2 is required for coat protein accumulation while ORF AL3 is necessary for efficient DNA replication. Virology 179: 69-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S.S., Radzio-Andzelm, E., and Hunter, T. 1995. How do protein-kinases discriminate between serine/threonine and tyrosine? Structural insights from the insulin receptor protein-tyrosine kinase. FASEB J. 9: 1255-1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torii K.U., Mitsukawa, N., Oosumi T., Matsuura, Y., Yo-koyama, R., Whittier, R.F., and Komeda, Y. 1996. The Arabidopsis ERECTA gene encodes a putative receptor protein kinase with extracellular leucine-rich repeats. Plant Cell 8: 735-746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhrig J.F., Soellick, T.-R., Minke, C.J., Philipp, C., Kellmann, J.-W., and Schreier, P.H. 1999. Homotypic interaction and multimerization of nucleocapsid protein of tomato spotted wilt tospovirus: Identification and characterization of two interacting domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96: 55-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Biezen E.A. and Jones, J.D.G. 1998. Plant disease resistance proteins and the gene-for-gene concept. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23: 454-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Hao, L., Shung, C.-Y., Sunter, G., and Bisaro, D.M. 2003. Adenosine kinase is inactivated by geminivirus AL2 and L2 proteins. Plant Cell 15: 3020-3032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward B.M., Medville, E., Lazarowitz, S.G., and Turgeon, R. 1997. The geminivirus BL1 movement protein is associated with endoplasmic reticulum-derived tubules in developing phloem cells. J. Virol. 71: 3726-3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]