Abstract

Background

Data on coagulation changes in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (PAF) are scarce. The aim of this study was to examine plasma antithrombin (AT) levels and activity as well as thrombin-antithrombin (TAT) complex levels in the early hours of the clinical manifestation of PAF.

Methods

Fifty-one patients (26 men and 25 women; mean age 59.84 ± 1.60 years) were consecutively selected with PAF duration < 24 hours, and 52 controls (26 men and 26 women; mean age 59.50 ± 1.46 years) matched the patients in terms of gender, age and comorbidities. Plasma levels and activity of AT and levels of the covalent TAT complex were studied once in each study participant.

Results

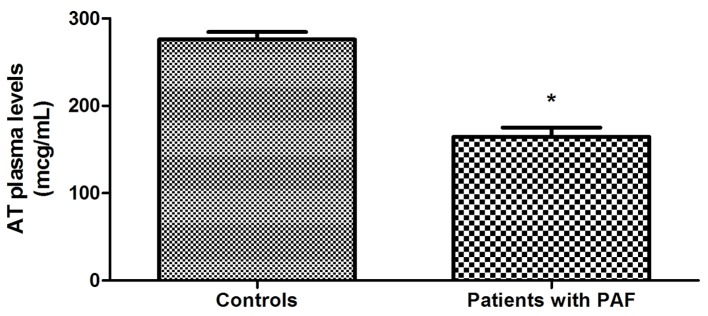

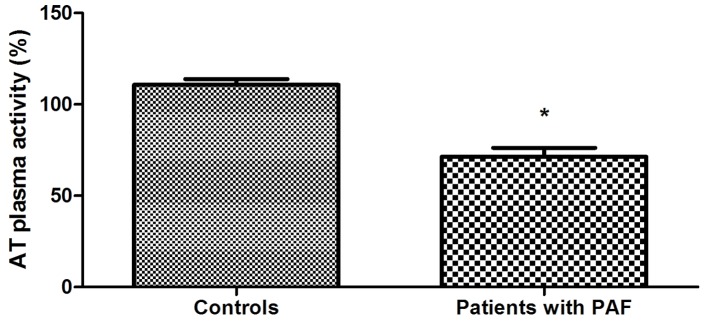

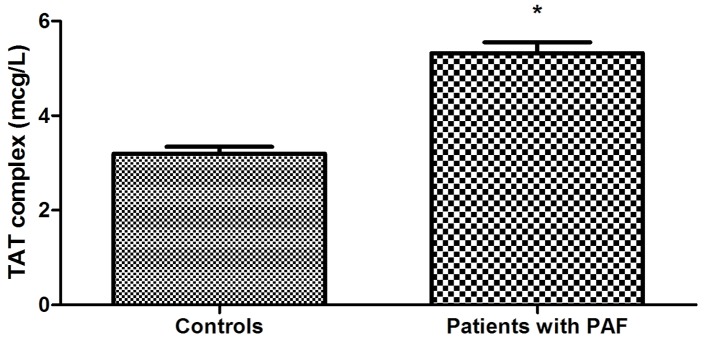

AT plasma levels in PAF patients were statistically significantly lower compared to controls (164.69 ± 10.51 vs. 276.21 ± 8.29 μg/mL, P < 0.001). Plasma activity of the anticoagulant was also significantly lower in PAF (71.33±4.87 vs. 110.72±3.09%, P < 0.001). TAT complex concentration in plasma was higher in the patient group (5.32 ± 0.23 vs. 3.20 ± 0.14 μg/L, P < 0.001).

Conclusion

We can say that PAF is associated with significantly reduced AT levels and activity and increased levels of TAT complex during the first 24 hours after its manifestation. These changes indicate a reduced activity of AT anticoagulant system, which is a probable prerequisite for the established enhanced coagulation (high TAT complex levels).

Keywords: Anticoagulant system, Coagulation, Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation

Introduction

Blood coagulation is an essential process for the human body and its fine regulation is one of the main processes responsible for blood fluidity. Blood coagulation is controlled by several anticoagulant systems, which under physiological conditions dominate the procoagulant forces [1].

The existence of the AT anticoagulant system was conceptualized in 1905 by Paul Moravitz, when he described the ability of plasma to neutralize thrombin activity. In 1965, Olav Egeberg presented for the first time a family with congenital AT deficiency, producing strong evidence for the clinical significance of the biomolecule [2]. After these initial discoveries a number of studies were conducted that shed a significant degree of clarity about AT structure and functions at molecular level.

Antithrombin (AT) is a 58-kDa molecule which belongs to the serine protease inhibitor (serpins) superfamily [3]. In its essence, it is a glycoprotein consisting of 432 amino-acid residues, and four of them glycosylated, to which oligosaccharide side chains are attached. Today, there is already indisputable evidence of the central role of AT in the regulation of blood coagulation. It is a powerful inhibitor of the coagulant cascade reactions [4]. One of its main effects is directed to the inactivation of the serine protease thrombin, a key factor for coagulation, which is responsible for the formation of fibrin monomers and their polymerization as well as stabilization of the fibrin clot [5, 6]. AT neutralizes thrombin by forming between them a stoichiometric thrombin-antithrombin (TAT) complex in which thrombin loses irreversibly its enzymatic activity.

It is appropriate to note that AT plays a key role in blood coagulation by providing an inhibitory effect on a number of other enzymes [7]. It inhibits the activity of FXa, and to a lesser extent, the activity of IXa, FXIa, and FXIIa [8, 9]. Its ability to limit coagulation through multiple interactions makes it one of the most important natural anticoagulant proteins. The physiological significance of AT anticoagulant system is best demonstrated by the rare, but almost always fatal in utero, homozygosity for AT deficiency [10, 11]. Therefore, changes in its plasma levels and activity have a significant impact on the anticoagulant protection of the body and are a commonly used laboratory coagulation indicator.

In this aspect, the study of AT within the covalent TAT complex is no less important. The levels of the complex reflect thrombin generation are a sensitive marker for the activation of intravascular coagulation [12, 13]. The study of TAT complex in plasma has a clinically significant value for the diagnosis and risk assessment of thromboembolic events.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a significant risk factor for thromboembolic events [14, 15]. The tendency to thrombogenesis in AF is a consequence of damages in all three components of the Virchow’s triad, namely, endothelial/endocardial damage or dysfunction, abnormal blood stasis (e.g., in the left atrial appendage), and blood constituents [16-18].

Attempts to reduce embolic burden in AF directed research interest toward hemostasis profile and particularly toward the complexly regulated coagulation/anticoagulation balance. In this aspect, most studied are the persistent and permanent forms of the disease. In recent years, however, clinical interest in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (PAF) increased significantly, after it was established that the risk of stroke and other embolic events in PAF is no less, compared to chronic AF [19]. Data on changes in coagulation in PAF and particularly in the earliest hours of the arrhythmia are extremely scarce.

Aim

The aim of the study was to examine the plasma AT levels and activity as well as TAT complex levels in the early hours of the clinical manifestation of PAF.

Materials and Methods

Study design

Accurate determination of the time of the occurrence and duration of PAF was crucial for this study. Therefore, only patients who could clearly define the onset of arrhythmia within 24 h of its manifestation by reporting a sudden onset of “palpitations”, continuing until hospitalization (respectively until blood sampling), were selected. Patients were diagnosed on the basis of electrocardiographic (ECG) immediately after admission to the ward and before blood sampling.

Patients’ uncertain about the onset of the rhythm disorder was not subject of research interest.

A control group was formed from volunteers, who visited their doctor for their annual examination.

The participants were included in the study after previously signing an informed consent to participate.

The same exclusion criteria (see below) were applied in selecting the patient and control group. AT levels and activity and levels of the covalent TAT complex in plasma were studied once in each study participant.

Exclusion criteria were: 1) Cardiovascular diseases, namely, ischemic heart disease; heart failure; uncontrollable hypertension; implanted device for the treatment of rhythm-conducive disorders; inflammatory and congenital heart diseases; moderate or severe valve diseases. 2) Other diseases: renal, liver or pulmonary diseases; diseases of the central nervous system; inflammatory and/or infectious diseases for the previous three months; neoplasmic and autoimmune diseases; diseases of the endocrine nervous system (except for diabetes mellitus type 2, non-insulin dependent, well controlled). 3) Intake of hormone-replacement therapy or contraceptives; pregnancy; systematic intake of analgesics, incl. non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; intake of antiplatelet drugs and anticoagulants; obesity (body mass index (BMI) > 35). 4) AF history and ECG data (only for the controls).

Study population

Fifty-one PAF patients (26 men and 25 women; mean age 59.84 ± 1.60 years) with PAF duration < 24 h, whose sinus rhythm was successfully restored by pharmacological cardioversion with propafenone, were consecutively selected for the study. The drug was administered immediately after the hospitalization of patients (after the collection of blood samples) in the prescribed for it scheme with a total duration of 24 h [20, 21].

The control group was formed by 52 volunteers (26 men and 26 women; mean age 59.50 ± 1.46 years) with no AF history or ECG data until the beginning of the study.

The study was conducted in the Intensive Coronary Care Unit of First Cardiology Clinic at the University Hospital “St. Marina”, Varna for the period October 2010 - May 2012 after approval by the Research Ethics Committee (No. 35/29.10.2010) at the same hospital and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [22].

Collection and storage of blood samples

In patients, blood samples were collected immediately after hospitalization prior to drug administration. In the control group, blood was taken during the prophylactic outpatient examination.

Blood samples (approximately 3.5 mL venous blood) were collected from the antecubital vein into coagulation tubes with 3.2% sodium citrate (VACUETTE, Greinet Bio-One North America, Inc.). After centrifuging at 2,500 g for 15 min, the resulting platelet poor plasma was stored in plastic tubes at -20 °C for up to 1 month.

Each indicator was determined twice, taking the average of the two measurements. Refreezing of samples was not allowed.

Laboratory procedures

We measured AT plasma levels by immune-turbidimetric assay (LIATEST AT III, Diagnostica Stago, France). A chromogenic assay was applied to determine AT activity in plasma (STA-Stachrome AT III, Diagnostica Stago, France). Quantitative measurement of plasma TAT complex levels was performed by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Enzygnost, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Products GmbH, Marburg, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Mean values, standard error of the mean (SEM), relative shares, and central tendency (Mo = mode) were calculated using descriptive statistics. Testing of the hypotheses for equality of means and relative share indicators was done by the Student’s two-tailed t-test for unpaired data for normal distributions.

All calculations were done with the GraphPad PRISM, Version 5.00. A probability value of P < 0.05 was considered significant in all statistical analyses. All results were expressed as mean ± SEM.

Results

There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups for the following indicators: gender, age, clinical characteristics, deleterious habits and BMI (Table 1) (P > 0.05).

Table 1. Patient and Control Group Clinical Data.

| Patients with PAF | Control group | P values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants in the group | 51 | 52 | 0.89 |

| Mean age (years) | 59.84 ± 1.60 | 59.50 ± 1.46 | 0.87 |

| Men/women | 26/25 | 26/26 | 1/0.93 |

| Accompanying diseases | |||

| Hypertension | 37 (72.54%) | 34 (65.38%) | 0.44 |

| Diabetes mellitus type 2 | 3 (5.88%) | 2 (3.84%) | 0.62 |

| Chronic ulcer disease | 2 (3.92%) | 0 | 0.15 |

| Status after hysterectomy | 2 (3.92%) | 1 (1.92%) | 0.54 |

| Benign prostatic hyperthrophy | 1 (1.96%) | 0 | 0.32 |

| Dyslipidemia | 4 (7.84%) | 3 (5.77%) | 0.69 |

| Medicaments for hypertension and dyslipidemia | |||

| Beta blockers | 19 (37.25%) | 17 (32.69%) | 0.62 |

| ACE inhibitors | 15 (29.41%) | 14 (26.92%) | 0.78 |

| Sartans | 11 (21.57%) | 9 (17.31%) | 0.58 |

| Statins | 4 (7.84%) | 3 (5.77%) | 0.69 |

| Deleterious habits | |||

| Smoking* | 8 (15.69%) | 7 (13.46%) | 0.75 |

| Alcohol intake** | 7 (13.72%) | 6 (11.53%) | 0.74 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.85 ± 0.46 | 24.95 ± 0.45 | 0.09 |

*Less than 0.5 pack (10 cigarettes)/week. Hospitalized patients had not smoked at least 24 h prior to the arrhythmia. Data from controls were taken after a 48-h non-smoking period. **No more than 2 drinks/week. Hospitalized patients had at least a 48-h period without alcohol prior to the arrhythmia. Data from controls were taken after a 48-h period without alcohol.

Transthoracic echocardiography found no significant differences between the patient and control groups (Table 2) (P > 0.05).

Table 2. Echocardiographic Indices of Patient and Control Group.

| Echocardiographic indicators | Patients with PAF | Control group | P values |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVEDD (mm) | 52.57 ± 0.58 | 52.29 ± 0.57 | 0.73 |

| LVESD (mm) | 34.43 ± 0.56 | 34.73 ± 0.48 | 0.69 |

| EF (%) | 62.98 ± 0.70 | 61.54 ± 0.58 | 0.12 |

| IVS (mm) | 10.37 ± 0.23 | 9.92 ± 0.26 | 0.20 |

| PW (mm) | 10.24 ± 0.21 | 9.73 ± 0.28 | 0.16 |

| LA volume (mL/m2) | 22.81 ± 0.45 | 23.82 ± 0.48 | 0.13 |

| RVEDD (mm) | 30.54 ± 1.58 | 29.17 ± 1.52 | 0.18 |

LVEDD: left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVESD: left ventricular end-systolic diameter; EF: ejection fraction; IVS: interventricular septum; PW: posterior wall; LA: left atrium; RVEDD: right ventricular end-diastolic volume.

Statistical analysis showed that all 51 patients were hospitalized between 2 and 24 h after the onset of the arrhythmia, most commonly during the fifth hour (Mo = 5; 10 of all 51 patients). The mean duration of AF episodes until hospitalization was 8.14 ± 0.76 h.

The study of hemostatic indicators found that AT plasma levels of PAF patients were statistically significantly lower compared to controls (164.69 ± 10.51 vs. 276.21 ± 8.29 μg/mL, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Plasma activity of the anticoagulant was also significantly lower in PAF (71.33±4.87 vs. 110.72±3.09%, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). TAT complex concentration in plasma was higher in the patient group (5.32 ± 0.23 vs. 3.20 ± 0.14 μg/L, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3).

Figure 1.

Comparison of AT plasma levels in patients with PAF and controls in sinus rhythm (*P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Comparison of AT activity in plasma in patients with PAF and controls in sinus rhythm (*P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Comparison of TAT complex levels in plasma in patients with PAF and controls in sinus rhythm (*P < 0.001).

Discussion

It is well known that AF is a condition with a high embologenic risk. Studies were on the coagulation system activity of established hypercoagulable state in the persistent and permanent form of arrhythmia. Specifically, increased fibrin turnover was reported in patients with chronic AF [23-26]. Moreover, statistical analysis showed that the changes are independent of comorbidities or structural heart diseases [23, 24]. Significantly increased plasma levels of TAT complexes, AT and prothrombic fragment 1+2 were measured in chronic non-rheumatic AF [27-29]. It was also found that the accumulation of cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, heart failure, stroke and others in AF is associated with an increase in coagulation indicators [30, 31].

Literature data to date undoubtedly show that the persistent and permanent forms of AF may manifest as a prothrombotic state caused by abnormal coagulation. However, data on coagulation status in PAF patients are scarce. They show a tendency to a hypercoagulable state in the clinical manifestations of the disease [32-35]. Logically, the question arises on how early in the course of PAF these changes occur. The answer undoubtedly has important clinical significance for the therapeutic approach to this form of the rhythm disorder. The literature search done by us found several studies examining coagulation in the early hours of the disease. There are established changes in D-dimer and TAT complexes indicators, giving reasons to the authors to assume that there is a procoagulant state [32, 36].

It is appropriate, however, to note that only single indicators are studied in groups with a very small number of patients, with some of them with structural heart diseases, in itself a prerequisite for hemostatic disorders.

In our study, we formed “pure” patient and control groups in terms of diseases (cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular) and drug treatment affecting the hemostasis profile. Moreover, the patient and control groups were equalized in terms of mean age, gender structure, deleterious habits, BMI and others (Tables 1 and 2). Thus, we believe the juxtaposition between the groups was objective at the maximum degree and this enabled us to study the effect of PAF on coagulation status.

In the presented study, AT plasma levels were significantly reduced in PAF patients (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). These variations could be interpreted as a consequence of reduced biosynthesis, reinforced clearance or anticoagulant consumption. Which is it, we can only guess. More significant in this case is that they themselves could explain the established low AT activity in the patient group (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

As we already mentioned, the formation of thrombin is a key step in the process of blood coagulation, and its inactivation by AT is one of the main anticoagulation pathways [5, 6]. In this sense, the measured low AT activity in the patient group is a major prerequisite for reduced activity of the anticoagulant system as a whole and creation of conditions for hypercoagulability in the early hours of the clinical manifestation of PAF.

Thrombin inhibition is carried out after the formation of the TAT complex. In the studied patient group, plasma levels of the complex were significantly higher than in controls (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3). In clinical practice, the increase in this indicator is considered as evidence of an active thrombotic process and is regarded as an early marker of prothrombotic and hypercoaguable states [37]. Therefore, the changes in TAT complex in PAF suggest intensive coagulation during the first 24 h of the clinical manifestation of the disease. They complement and validate the low AT activity levels. The established variations in the three studied indicators create a prerequisite for the manifestation of thromboembolic events. Moreover, they demonstrate the need for the earliest possible termination of the arrhythmia and restoration of sinus rhythm. Last but not least, it is appropriate to note that there are currently no randomized controlled studies giving specific recommendations for anticoagulant therapy in PAF with episode duration < 24 h. Our results give a good reason to conduct further studies with a view to the need for mandatory application of anticoagulants in the early hours of PAF.

In conclusion, we can say that PAF is associated with significantly reduced AT levels and activity and increased levels of TAT complex during the first 24 h after its manifestation. These changes indicate a reduced activity of AT anticoagulant system, which is a probable prerequisite for the established enhanced coagulation (high TAT complex levels).

Grants

The study was not supported by any grants or funding agencies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have declared that no conflicts of interest exist.

References

- 1.Esmon CT. The protein C pathway. Chest. 2003;124(3 Suppl):26S, 32S. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.3_suppl.26S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Egeberg O. Inherited Antithrombin Deficiency Causing Thrombophilia. Thromb Diath Haemorrh. 1965;13:516–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maclean PS, Tait RC. Hereditary and acquired antithrombin deficiency: epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatment options. Drugs. 2007;67(10):1429–1440. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200767100-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olds RJ, Lane DA, Mille B, Chowdhury V, Thein SL. Antithrombin: the principal inhibitor of thrombin. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1994;20(4):353–372. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1001927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker CP, Royston D. Thrombin generation and its inhibition: a review of the scientific basis and mechanism of action of anticoagulant therapies. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88(6):848–863. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.6.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolberg AS. Thrombin generation and fibrin clot structure. Blood Rev. 2007;21(3):131–142. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abildgaard U. Antithrombin - early prophecies and present challenges. Thromb Haemost. 2007;98(1):97–104. doi: 10.1160/th07-04-0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li W, Johnson DJ, Esmon CT, Huntington JA. Structure of the antithrombin-thrombin-heparin ternary complex reveals the antithrombotic mechanism of heparin. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11(9):857–862. doi: 10.1038/nsmb811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patnaik MM, Moll S. Inherited antithrombin deficiency: a review. Haemophilia. 2008;14(6):1229–1239. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wells PS, Blajchman MA, Henderson P, Wells MJ, Demers C, Bourque R, McAvoy A. Prevalence of antithrombin deficiency in healthy blood donors: a cross-sectional study. Am J Hematol. 1994;45(4):321–324. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830450409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finazzi G, Caccia R, Barbui T. Different prevalence of thromboembolism in the subtypes of congenital antithrombin III deficiency: review of 404 cases. Thromb Haemost. 1987;58(4):1094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seitz R, Egbring R, Wagner C, Dati F. [Thrombin-antithrombin III complex (TAT): a marker for activation of intravascular coagulation] Internist (Berl) 1990;31(1):69–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deguchi K, Noguchi M, Yuwasaki E, Endou T, Deguchi A, Wada H, Murashima S. et al. Dynamic fluctuations in blood of thrombin/antithrombin III complex (TAT) Am J Hematol. 1991;38(2):86–89. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830380203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reiffel JA. Atrial fibrillation and stroke: epidemiology. Am J Med. 2014;127(4):e15, 16. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lip GY. Stroke in atrial fibrillation: epidemiology and thromboprophylaxis. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(Suppl 1):344–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watson T, Shantsila E, Lip GY. Mechanisms of thrombogenesis in atrial fibrillation: Virchow's triad revisited. Lancet. 2009;373(9658):155–166. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatzinikolaou-Kotsakou E, Kartasis Z, Tziakas D, Hotidis A, Stakos D, Tsatalas K, Bourikas G. et al. Atrial fibrillation and hypercoagulability: dependent on clinical factors or/and on genetic alterations? J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2003;16(3):155–161. doi: 10.1023/B:THRO.0000024053.45693.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medi C, Hankey GJ, Freedman SB. Stroke risk and antithrombotic strategies in atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2010;41(11):2705–2713. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.589218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lip GY, Hee FL. Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. QJM. 2001;94(12):665–678. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/94.12.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bellandi F, Cantini F, Pedone T, Palchetti R, Bamoshmoosh M, Dabizzi RP. Effectiveness of intravenous propafenone for conversion of recent-onset atrial fibrillation: a placebo-controlled study. Clin Cardiol. 1995;18(11):631–634. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960181108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bianconi L, Mennuni M. Comparison between propafenone and digoxin administered intravenously to patients with acute atrial fibrillation. PAFIT-3 Investigators. The Propafenone in Atrial Fibrillation Italian Trial. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82(5):584–588. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(98)00412-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. 59th WMA General Assembly. Seoul. 2008.

- 23.Lip GY, Lowe GD, Rumley A, Dunn FG. Increased markers of thrombogenesis in chronic atrial fibrillation: effects of warfarin treatment. Br Heart J. 1995;73(6):527–533. doi: 10.1136/hrt.73.6.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumagai K, Fukunami M, Ohmori M, Kitabatake A, Kamada T, Hoki N. Increased intracardiovascular clotting in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;16(2):377–380. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90589-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gustafsson C, Blomback M, Britton M, Hamsten A, Svensson J. Coagulation factors and the increased risk of stroke in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 1990;21(1):47–51. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.21.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lip GY, Lip PL, Zarifis J, Watson RD, Bareford D, Lowe GD, Beevers DG. Fibrin D-dimer and beta-thromboglobulin as markers of thrombogenesis and platelet activation in atrial fibrillation. Effects of introducing ultra-low-dose warfarin and aspirin. Circulation. 1996;94(3):425–431. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.94.3.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turgut N, Akdemir O, Turgut B, Demir M, Ekuklu G, Vural O, Ozbay G. et al. Hypercoagulopathy in stroke patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: hematologic and cardiologic investigations. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2006;12(1):15–20. doi: 10.1177/107602960601200104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kahn SR, Solymoss S, Flegel KM. Nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: evidence for a prothrombotic state. CMAJ. 1997;157(6):673–681. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asakura H, Hifumi S, Jokaji H, Saito M, Kumabashiri I, Uotani C, Morishita E. et al. Prothrombin fragment F1 + 2 and thrombin-antithrombin III complex are useful markers of the hypercoagulable state in atrial fibrillation. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1992;3(4):469–473. doi: 10.1097/00001721-199203040-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varughese GI, Patel JV, Tomson J, Lip GY. The prothrombotic risk of diabetes mellitus in atrial fibrillation and heart failure. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(12):2811–2813. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inoue H, Nozawa T, Okumura K, Jong-Dae L, Shimizu A, Yano K. Prothrombotic activity is increased in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and risk factors for embolism. Chest. 2004;126(3):687–692. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.3.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sohara H, Amitani S, Kurose M, Miyahara K. Atrial fibrillation activates platelets and coagulation in a time-dependent manner: a study in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29(1):106–112. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(96)00427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giansante C, Fiotti N, Miccio M, Altamura N, Salvi R, Guarnieri G. Coagulation indicators in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: effects of electric and pharmacologic cardioversion. Am Heart J. 2000;140(3):423–429. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2000.108520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li-Saw-Hee FL, Blann AD, Gurney D, Lip GY. Plasma von Willebrand factor, fibrinogen and soluble P-selectin levels in paroxysmal, persistent and permanent atrial fibrillation. Effects of cardioversion and return of left atrial function. Eur Heart J. 2001;22(18):1741–1747. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iga K, Izumi C, Inoko M, Kitaguchi S, Himura Y, Gen H, Konishi T. Increased thrombin-antithrombin III complex during an episode of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 1998;66(2):153–156. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5273(98)00211-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marin F, Roldan V, Climent VE, Ibanez A, Garcia A, Marco P, Sogorb F. et al. Plasma von Willebrand factor, soluble thrombomodulin, and fibrin D-dimer concentrations in acute onset non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation. Heart. 2004;90(10):1162–1166. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.024521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montaner J. Blood biomarkers to guide stroke thrombolysis. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2009;1:200–208. doi: 10.2741/E19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]