Abstract

Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) are increasingly important nosocomial pathogens and screening for colonization status is a mainstay in infection control. We implemented PCR-based screening during vanA-positive Enterococcus faecium outbreaks in four university hospitals in Copenhagen, Denmark. Xpert®vanA/vanB was performed directly on rectal swabs and the vanA PCR result was used to guide infection control measures. Concurrently, all samples were selectively cultured including an overnight enrichment step. Diagnostic accuracy was calculated as well as turnaround time and the impact of the earlier available PCR results on infection control decision making. In all, 1110 samples were analysed. The vanA PCR positivity rate was 13.8% and culture positivity rate was 15.2%. The diagnostic accuracy of the vanA part of the assay was high with a sensitivity of 87.1%, a specificity of 99.7%, and positive and negative predictive values of 98.0% and 97.7%, respectively. The vanB PCR had a considerably lower specificity of 77.6% and a positive predictive value of 0.4%. In 1067 (96.1%) samples, PCR results were reported within 1 day, whereas median culture turnaround time was 3 days. The saving of time to available results corresponded to 141 saved isolation days and 292 saved transmission risk days. False-negative or false-positive PCR results led to six additional transmission risk days and 13 additional isolation days, respectively.

The vanA PCR had high diagnostic accuracy and the prompt availability of results gave a considerable benefit for infection control decision making.

Keywords: Infection control, molecular screening, PCR-based screening, selective culture, vanA, vancomycin-resistant enterococci

Introduction

Glycopeptide resistance was detected in enterococci more than 25 years ago [1], [2]; since then, vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) have become important nosocomial pathogens associated with high mortality and costs [3], [4], [5], [6]. Glycopeptide resistance in enterococci is mediated by van genes, with vanA and vanB being the most prevalent [4]. Several European countries have reported a rising incidence of VRE in recent years [3], [7], [8]. In Denmark, a dramatic increase since 2012 has been due to multiclonal outbreaks of vanA-positive Enterococcus faecium [9], [10].

It has been estimated that for every patient with a VRE infection detected in a clinical sample, up to ten patients are intestinal carriers of VRE [6]. Therefore, current guidelines recommend screening of patients at risk and implementation of isolation precautions for VRE carriers [11], [12]. Screening relies on selective culturing and/or detection of the resistance genes vanA or vanB by PCR [13]. The latter provides faster results, but is more costly. However, substantial indirect savings can be achieved by rapidly available results, as highlighted by a report from France, which compared the management of two simultaneous VRE outbreaks on two different wards [14]. Several studies have examined the diagnostic accuracy of various assays to detect vanA and vanB with or without a previous enrichment step [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23]. Most studies showed a high diagnostic accuracy of vanA gene detection. However, sensitivities ranging from 43.5% to 100% and specificities from 79.2% to 99.6% have been reported. In contrast, the specificity of the detection of the vanB gene is considerably lower [16], [17], [22], which is attributed to the presence of vanB-positive anaerobic bacteria [24], [25].

In our laboratory, we have used a culture-based method using overnight enrichment and subsequent plating on chromogenic agar to screen for VRE. In autumn 2014, prompted by long-lasting VRE outbreaks, we implemented the Xpert® vanA/vanB assay performed directly on rectal swabs. This fully automated system integrating DNA extraction and real-time PCR provides results within an hour. We used the vanA part of the assay to guide rapid implementation of infection control measures. Here, we evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of the Xpert® vanA/vanB assay and the impact on infection control decision making.

Materials and methods

Setting

Our laboratory serves the primary and secondary sectors of a population of 800 000 inhabitants in the northern part of the Capital Region of Denmark, including four university hospitals with a total number of 1577 beds and covering all internal medicine subspecialties and three intensive care units. The infection control units at these four hospitals are part of the clinical microbiology department and employ six infection control nurses.

Infection control measures

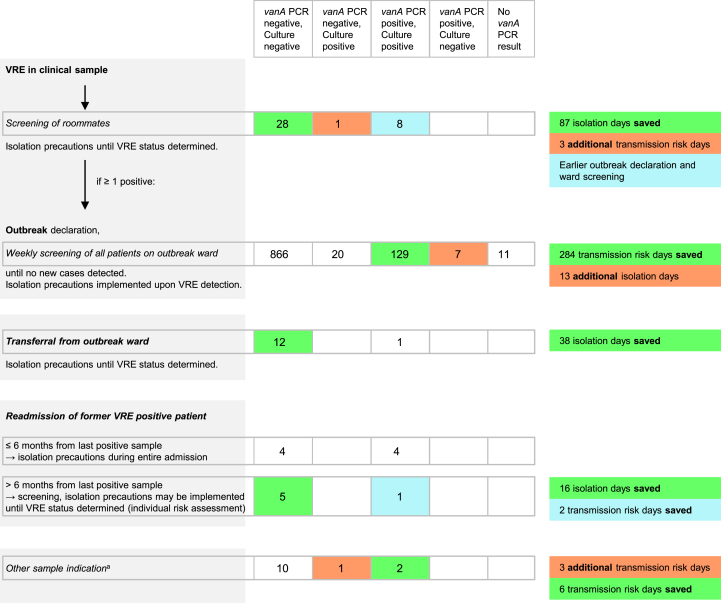

Our infection control algorithm is shown in Fig. 1. For all VRE-positive patients, isolation precautions are implemented. Diagnosis of VRE in a clinical sample results in roommate screening and isolation precautions are implemented until results are available. If any roommate is found positive, an outbreak is declared and all patients in the ward are screened weekly until no new patient is diagnosed with VRE. During weekly screenings, isolation precautions are implemented as soon as a positive VRE result is available. For roommate screening and weekly screening of wards, the routine culture-based screening is supplemented by vanA PCR. Before transfer of patients from an outbreak ward, PCR is performed and the implementation of isolation precautions is based on the PCR result. For VRE-positive patients readmitted within 6 months after the last positive screening sample, isolation precautions are implemented at admission independently from screening results. In the case of readmission > 6 months after the last positive sample, screening is advised and the implementation of isolation precautions is individualized based on screening results and risk factors. In these cases, PCR is eventually performed.

Fig. 1.

Infection control algorithm and impact of vanA PCR results from 1110 samples on infection control measures. Left: infection control algorithm and sample indication (italicized); centre: sample count and results stratified by indication; right: impact on infection control decision making. aAdmission or transferral from non-outbreak wards (n = 9), follow-up sample after former discordant result (n = 1), unknown indication (n = 3).

Laboratory methods

Rectal swabs were taken with ESwab (Copan, Brescia, Italy). For phenotypic screening, ESwab transport medium was transferred to an enrichment broth (brain–heart infusion supplemented with 4 mg/L vancomycin and 60 mg/L aztreonam) either by shaking the flocked swab several times in the enrichment medium or by pipetting 100 μL. After overnight incubation, 100 μL of the enrichment medium was plated on selective chromogenic agar plates (CHROMagarTM VRE, CHROMagar, Paris, France) and read after 1 and 2 days of incubation. For vanA PCR-positive, but culture-negative samples, the culture protocol was thoroughly repeated. Species identification was performed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (BioTyper, Bruker, Bremen, Germany) and a preliminary positive result was given if there was abundant growth of E. faecium on the selective chromogenic agar. Susceptibility testing for vancomycin and teicoplanin was performed by the EUCAST disc diffusion method [26] and determination of the MIC used a gradient strip (Etest, bioMérieux, Solna, Sweden) to confirm the vanA or vanB phenotype. PCR-based screening was undertaken by the automated system GeneXpert using the Xpert® vanA/vanB assay (Cepheid AB, Solna, Sweden). One hundred microlitres of the ESwab transport medium was added to the sample reagent and further handled as recommended by the manufacturer. In case of invalid or error results (PCR inhibition or technical error), the assay was repeated once. Only vanA PCR results were reported to the requesting wards as a preliminary result and used for guidance of infection control measures. The vanB PCR results were not reported. PCR was performed on the same day if the sample arrived in the laboratory before 16.00 h, all days of the week.

Data collection

Sample arrival date, laboratory results, dates of preliminary and final results and sample indications were prospectively collected. For final analysis, data were supplemented with patient identification from the laboratory information system. The impact of the vanA PCR result on infection control measures was estimated by calculation of ‘isolation days saved’ (number of days from negative PCR result to final negative culture result) and ‘transmission risk days saved’ (number of days from positive PCR result to preliminary or final positive culture result).

Statistical analysis

The computer program “R: A language and environment for statistical computing”, version 3.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; http://www.R-project.org/) was used for statistical analysis. For comparison of categorical data, Fisher’s exact test was used. For comparison of numerical data, unpaired groups, the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used. Two-sided p ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values with 95% CI were calculated using the R package DTComPair.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Danish Health and Medicines Authority (Record no. 3-3013-1217/1/) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (Record no. 2012-58-0004; HEH-2015-066).

Results

From 30 December 2014 to 15 August 2015, 1110 VRE screening samples from 804 patients were examined both by the culture-based method and by PCR. The samples were from 24 different departments from four different hospitals. In 1067 (96.1%) samples, PCR was performed and reported the same day, the sample was received in the laboratory. The median turnaround time for culture results was 3 days (mean 3.2; range 3–9 days).

In 35 (3.2%) samples, invalid or error results were obtained after the first PCR analysis and for 11 (1.0%) samples, repeated analysis did not give a result either. Of the 1099 samples where a PCR result was obtained, 152 (13.8%) were positive for the vanA gene and 167 (15.2%) were culture-positive for an Enterococcus species (all E. faecium) with the vanA phenotype (vancomycin-resistant with MIC ≥256 mg/L and teicoplanin-resistant with MIC 8–256 mg/L). The vanA PCR results in relation to culture results are given in Table 1. The vanB PCR was positive in 247 (22.5%) samples, but only one was culture-positive for Enterococcus sp. (Enterococcus faecalis) with the vanB phenotype (vancomycin-resistant with MIC 128 mg/L and teicoplanin-susceptible with MIC 0.5 mg/L), as shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Results for the vanA PCR of the Xpert® vanA/vanB assay, in relation to culture results

| Culture negative, n (%) | vanA Enterococcus faecium culture positive, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| PCR vanA-negative | 925 (84.2%) | 22 (2.0%)a |

| PCR vanA-positive | 7 (0.6%) | 145 (13.2%)b |

Eight samples were only positive on evaluation of chromogenic plate after 2 days of incubation.

Ten samples were only positive on evaluation of chromogenic plate after 2 days of incubation.

Table 2.

Results for the vanB PCR of the Xpert® vanA/vanB assay, in relation to culture results

| Culture negative, n (%) | vanB Enterococcus faecalis culture positive, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| PCR vanB-negative | 852 (77.5%) | 0 |

| PCR vanB-positive | 246 (22.3%) | 1 (0.1%) |

Discrepant results between culture and vanA PCR were further investigated. In 12 of the 22 PCR-negative samples, from which a vanA phenotype E. faecium was cultured, PCR was repeated on the ESwab transport medium and two were found positive with high circles of threshold (Ct) of 36.9 and 38.2. PCR was also performed on the isolates from the 20 remaining samples and they were all vanA PCR-positive. Of the 145 culture-positive samples that had been vanA PCR-positive, most (n = 135) were culture positive after 1 day of incubation of the chromogenic agar, whereas the remaining ten samples (6.9%) were only positive after 2 days of incubation. In comparison, eight of the 22 culture-positive samples that had been PCR-negative (36.4%) only turned positive on the second day of incubation (Fisher's Exact Test, p < 0.001).

On the other hand, seven samples were found vanA PCR-positive, but culture-negative. Ct values of the culture-negative sample were significantly higher (median 32.9; range 24.1–38.3) than Ct values of the culture-positive samples (median 22.9; range 12.8–37.8) (Wilcoxon rank sum test; p < 0.001).

To calculate the test accuracy of the Xpert® vanA/vanB assay, culture results complemented with information from the patient’s earlier and later samples were used as a reference standard. For the analysis of vanA PCR, four of seven vanA PCR-positive, but culture-negative samples were classified as ‘true positives’: three samples from the same patient from which phenotypically vancomycin-susceptible (MIC 1 mg/L), but vanA-positive E. faecium was isolated by non-selective culturing (unpublished data, Holzknecht BJ) and one sample taken under linezolid therapy from a patient with VRE culture-positive samples 15 days earlier and 28 days later. The sensitivity of the vanA PCR assay was 87.1% (95% CI 82.1%–92.2%), the specificity was 99.7% (95% CI 99.3%–100%) and the positive and negative predictive values were 98.0% (95% CI 95.8%–100%) and 97.7% (95% CI 96.7%–98.6%), respectively. The specificity and positive predictive value of the vanB part of the assay were low at 77.6% (95% CI 75.1%–80.1%) and 0.4% (95% CI 0.00%–1.2%), respectively.

The majority of the samples (n = 1033; 93.1%) were taken as weekly screening samples from 12 different outbreaks during the study period. Thirty-seven (3.3%) were roommate screening samples, 14 (1.3%) were taken at readmission, 13 (1.2%) at transferral from outbreak wards and 13 (1.2%) for other indications (Fig. 1). A total of 141 isolation days could be saved as a consequence of faster available negative PCR results. The saving of time due to rapidly available positive PCR results corresponded to a total of 292 saved transmission risk days. On the other hand, false-negative or false-positive PCR resulted in six additional transmission risk days and 13 additional isolation days (Fig. 1).

Discussion

This study describes the performance and impact of the Xpert® vanA/vanB assay, when performed directly on rectal swabs, in the setting of vanA E. faecium outbreaks.

Of the 1099 samples with available PCR and culture results, only 29 showed discordant results: seven were vanA PCR-positive, but culture-negative and 22 were culture-positive, but vanA PCR-negative. Vancomycin-resistant isolates cultured from samples that had been PCR-negative, were vanA PCR-positive, which confirms that false-negative PCR results, when performed directly on the sample, were not due to alterations of the primer binding sites. Two results suggest that discordant results often occurred in samples with low bacteria counts. Ct-values of vanA PCR-positive, culture-negative samples were significantly higher than Ct-values in culture-positive samples. Likewise, the culture-positive, but vanA PCR-negative samples were significantly more often positive after 2 days of incubation of the chromogenic plate than PCR-positive samples, which might also indicate a lower bacteria count. In the implementation phase of the Xpert® vanA/vanB assay, investigation of vanA PCR-positive, culture-negative samples had actually led to a change in the culture protocol from plating 10 μL to 100 μL of enrichment broth on the chromogenic plates to increase sensitivity (data not shown).

Using culture results complemented with information from patients’ follow-up samples as a reference standard, the diagnostic accuracy of the vanA part of the Xpert® vanA/vanB assay was excellent and in accordance with previous studies [20], [22], [23]. However, one previous, but far smaller, study found both a lower sensitivity and a lower specificity of the assay [19]. As there was only one sample that was culture-positive for vanB-positive VRE, we could not fully analyse the diagnostic accuracy of the vanB part of the assay. However, the large proportion (22.3%) of false-positive vanB PCR results is in accordance with previous studies [16], [17], [21], [22], [23].

Two findings underline the strength of PCR-based screening. First, investigation of vanA PCR-positive, culture-negative samples from the same patient led to the isolation of phenotypically vancomycin-susceptible, but vanA PCR-positive E. faecium. An outbreak with a similar strain has been described and infection control management similar to VRE seems prudent [27], [28]. Second, a presumably false-negative culture result was obtained under linezolid therapy.

The strengths of the diagnostic accuracy study are the large sample size and the prospective and thorough comparison of the Xpert® vanA/vanB assay with the selective culture method, including further investigation of discordant samples by follow-up samples to define a robust reference standard. Drawbacks are that we report a single-centre study. However, it has been shown that several outbreak clones and multilocus sequence types are circulating in our region [10]. A systematic study of genetically diverse strains would though be necessary to finally conclude on the generalizability of our results.

Using the Xpert® vanA/vanB assay, 96.1% of screening results were available within 1 day, whereas the median turnaround time for selective culturing was 3 days. Based on the time interval between available PCR and culture results, we calculated saved isolation days and saved transmission risk days as a consequence of earlier suspension or implementation of isolation measures. However, these numbers might be overestimated, as patients might have been isolated for other reasons or dismissed from the hospital before results were available. Besides saved transmission risk days, earlier available positive screening results from roommates also led to faster outbreak declaration and implementation of additional infection control measures such as screening of all patients, enhanced cleaning, enforcement of hand hygiene and staff teaching. We have seen a faster control of VRE outbreaks after the implementation of PCR-based screening. However, as this is part of a bundle approach we cannot determine the isolated value of the PCR assay (Mogensen and Midttun, Infection Prevention And Control Canada 2016 National Education Conference, Poster 84). Detailed health economics calculations are beyond the scope of this study. However, considering the assay’s official price in Denmark of 661 DKK (approx. € 89) per sample and estimated additional costs per isolation day of 3350 DDK (approx. € 451) [29], we feel that saving 141 isolation days and 292 transmission risk days as a result of 1110 PCR analyses is a considerable impact and worth the costs. This is more important when the psychosocial consequences of a VRE outbreak situation and isolation precautions for patients and staff members are also taken into account. We have therefore maintained the assay for VRE outbreak management.

In conclusion, the vanA PCR of the Xpert® vanA/vanB assay had a high diagnostic accuracy and considerable impact on infection control decision making in our setting.

Transparency declaration

BJH received personal fees from MSD, outside the submitted work. LN received non-financial support from ROCHE Diagnostics A/S and from MSD, outside the submitted work. DSH, AK and JOJ have nothing to disclose.

Author contributions

BJH contributed to conception and design of the study, acquisition and analysis of data and drafting of the manuscript. DSH and JOJ contributed to conception and design of the study and critical revision of the manuscript. LN contributed to acquisition of data and critical revision of the manuscript. AK contributed to conception of the study, acquisition of data and critical revision of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Kamilla Søby Henriksen, Betina Damm Jensen and Stefanie Mørk Christensen for excellent technical assistance and Ram B. Dessau for help with the statistical analysis.

References

- 1.Leclercq R., Derlot E., Duval J., Courvalin P. Plasmid-mediated resistance to vancomycin and teicoplanin in Enterococcus faecium. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:157–161. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198807213190307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uttley A.H., Collins C.H., Naidoo J., George R.C. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Lancet. 1988;1(8575-6):57–58. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Werner G., Coque T.M., Hammerum A.M., Hope R., Hryniewicz W., Johnson A. Emergence and spread of vancomycin resistance among enterococci in Europe. Euro Surveill. 2008;13(47) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cetinkaya Y., Falk P., Mayhall C.G. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:686–707. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.4.686-707.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cattoir V., Leclercq R. Twenty-five years of shared life with vancomycin-resistant enterococci: is it time to divorce? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:731–742. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mascini E.M., Bonten M.J. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci: consequences for therapy and infection control. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11(Suppl 4):43–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gastmeier P., Schroder C., Behnke M., Meyer E., Geffers C. Dramatic increase in vancomycin-resistant enterococci in Germany. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:1660–1664. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourdon N., Fines-Guyon M., Thiolet J.M., Maugat S., Coignard B., Leclercq R. Changing trends in vancomycin-resistant enterococci in French hospitals, 2001–08. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:713–721. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Statens Serum Institut. EPI-NEWS No 16/17 – 2014. Available at: http://www.ssi.dk/English/News/EPI-NEWS/2014/No%2017%20-%202014.aspx; accessed 20 December 2016.

- 10.Pinholt M., Larner-Svensson H., Littauer P., Moser C.E., Pedersen M., Lemming L.E. Multiple hospital outbreaks of vanA Enterococcus faecium in Denmark, 2012–13, investigated by WGS, MLST and PFGE. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:2474–2482. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muto C.A., Jernigan J.A., Ostrowsky B.E., Richet H.M., Jarvis W.R., Boyce J.M. SHEA guideline for preventing nosocomial transmission of multidrug-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24:362–386. doi: 10.1086/502213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weber S.G., Huang S.S., Oriola S., Huskins W.C., Noskin G.A., Harriman K. Legislative mandates for use of active surveillance cultures to screen for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococci: position statement from the Joint SHEA and APIC Task Force. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:249–260. doi: 10.1086/512261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faron M.L., Ledeboer N.A., Buchan B.W. Resistance mechanisms, epidemiology, and approaches to screening for vancomycin resistant Enterococcus in the health care setting. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:2436–2447. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00211-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birgand G., Ruimy R., Schwarzinger M., Lolom I., Bendjelloul G., Houhou N. Rapid detection of glycopeptide-resistant enterococci: impact on decision-making and costs. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2013;2(1):30. doi: 10.1186/2047-2994-2-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang H., Nord C.E., Ullberg M. Screening for vancomycin-resistant enterococci: results of a survey in Stockholm. APMIS. 2010;118:413–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2010.02605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Werner G., Serr A., Schutt S., Schneider C., Klare I., Witte W. Comparison of direct cultivation on a selective solid medium, polymerase chain reaction from an enrichment broth, and the BD GeneOhm VanR Assay for identification of vancomycin-resistant enterococci in screening specimens. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;70:512–521. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mak A., Miller M.A., Chong G., Monczak Y. Comparison of PCR and culture for screening of vancomycin-resistant Enterococci: highly disparate results for vanA and vanB. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:4136–4137. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01547-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marner E.S., Wolk D.M., Carr J., Hewitt C., Dominguez L.L., Kovacs T. Diagnostic accuracy of the Cepheid GeneXpert vanA/vanB assay ver. 1.0 to detect the vanA and vanB vancomycin resistance genes in Enterococcus from perianal specimens. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;69:382–389. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zabicka D., Strzelecki J., Wozniak A., Strzelecki P., Sadowy E., Kuch A. Efficiency of the Cepheid Xpert vanA/vanB assay for screening of colonization with vancomycin-resistant enterococci during hospital outbreak. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2012;101:671–675. doi: 10.1007/s10482-011-9681-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Babady N.E., Gilhuley K., Cianciminio-Bordelon D., Tang Y.W. Performance characteristics of the Cepheid Xpert vanA assay for rapid identification of patients at high risk for carriage of vancomycin-resistant Enterococci. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:3659–3663. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01776-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stamper P.D., Cai M., Lema C., Eskey K., Carroll K.C. Comparison of the BD GeneOhm VanR assay to culture for identification of vancomycin-resistant enterococci in rectal and stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3360–3365. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01458-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bourdon N., Berenger R., Lepoultier R., Mouet A., Lesteven C., Borgey F. Rapid detection of vancomycin-resistant enterococci from rectal swabs by the Cepheid Xpert vanA/vanB assay. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;67:291–293. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gazin M., Lammens C., Goossens H., Malhotra-Kumar S. Evaluation of GeneOhm VanR and Xpert vanA/vanB molecular assays for the rapid detection of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:273–276. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1306-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ballard S.A., Pertile K.K., Lim M., Johnson P.D., Grayson M.L. Molecular characterization of vanB elements in naturally occurring gut anaerobes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:1688–1694. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.5.1688-1694.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graham M., Ballard S.A., Grabsch E.A., Johnson P.D., Grayson M.L. High rates of fecal carriage of nonenterococcal vanB in both children and adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1195–1197. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00531-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Available at: http://www.eucast.org. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Szakacs T.A., Kalan L., McConnell M.J., Eshaghi A., Shahinas D., McGeer A. Outbreak of vancomycin-susceptible Enterococcus faecium containing the wild-type vanA gene. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:1682–1686. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03563-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thaker M.N., Kalan L., Waglechner N., Eshaghi A., Patel S.N., Poutanen S. Vancomycin-variable enterococci can give rise to constitutive resistance during antibiotic therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:1405–1410. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04490-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jakobsen M., Skovgaard C.M.B., Jensen M.L., Wolf R.T., Rasmussen S.R. Det Nationale Institut for Kommuners og Regioners Analyse og Forskning (KORA); 2015. Omkostninger ved husdyr-MRSA for sundhedsvæsenet i Danmark.http://www.kora.dk/udgivelser/udgivelse/i11589/Omkostninger-ved-husdyr-MRSA-for-sundhedsvaesenet-i-Danmark Available at: accessed 20 December 2016. [Google Scholar]