Abstract

This work reports on incorporation of spectrally tuned gold/silica (Au/SiO2) core/shell nanospheres and nanorods into the inverted perovskite solar cells (PVSC). The band gap of hybrid lead halide iodide (CH3NH3PbI3) can be gradually increased by replacing iodide with increasing amounts of bromide, which can not only offer an appreciate solar radiation window for the surface plasmon resonance effect utilization, but also potentially result in a large open circuit voltage. The introduction of localized surface plasmons in CH3NH3PbI2.85Br0.15‐based photovoltaic system, which occur in response to electromagnetic radiation, has shown dramatic enhancement of exciton dissociation. The synchronized improvement in photovoltage and photocurrent leads to an inverted CH3NH3PbI2.85Br0.15 planar PVSC device with power conversion efficiency of 13.7%. The spectral response characterization, time resolved photoluminescence, and transient photovoltage decay measurements highlight the efficient and simple method for perovskite devices.

Keywords: hybrid, optical manipulation, perovskite, solar cell, surface plasmon resonance

1. Introduction

Solar cells using hybrid lead halide perovskite as light harvester have evidenced significant progress in the past few years.1, 2, 3, 4 Currently, the certified efficiency for perovskite solar cells (PVSC) is 20.1% and expected to improve further.5 This success is closely associated with the photoelectrical properties of the specific light absorber, such as CH3NH3PbX3 (X = I, Br, Cl), exhibiting an appropriate band gap, small exciton binding energy, and long and balanced ambipolar charge transport.6, 7 Most efficient perovskite devices rely on the p‐i‐n heterojunction structure, in which TiO2 and 2,2′,7,7′‐tetrakis (N,N‐di‐p‐methoxyphenylamine)‐9,9′‐spirobifluorene (spiro‐MeOTAD) are the widely used electron and hole transporting materials, owing to their good optical transparency and well band alignment with respect to CH3NH3PbI3.8, 9 Recently, an emerged inverted PVSC, has attracted intensive interests, in which the photo‐induced holes are collected at the front transparent conductive glass substrate after photoexcitation.10 – 12 Perovskite devices will be certainly benefited from new materials and device configurations, and thus, resolving some obstacles existing in the conventional cells, such as the current–voltage scan hysteresis.13, 14 Recently, the elimination of photocurrent hysteresis in the inverted CH3NH3PbI3‐based solar cells has been demonstrated by different groups.15, 16

Poly(3,4‐ethylenedioxythiophene) poly(styrene‐sulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) has been used as hole selective contact in inverted perovskite cells, achieving outstanding power conversion efficiency (PCE) of about 15%.17, 18 Meanwhile, NiO‐based PVSCs have also shown growing attention, due to its high stability and electrical conductivity.19 – 21 For example, a faster charge transfer between NiO and charge transfer materials than that of TiO2 has been revealed with scanning electrochemical microscopy.21 Chen et al. first reported the replacement of PEDOT:PSS with a thin NiO hole selective layer, resulting in a PCE of 7.8%.11 We applied a reactive magnetron sputtered NiO ultrathin layer to promote the efficiency up to 9.8%.22 Subsequently, Chen et al. proposed a hybrid interfacial layer with an important “dual blocking effect,” resulting in PCE of ≈13.5%.23 Recently, CH3NH3PbI3‐based solar cell with 15.4% PCE was demonstrated by using solution‐processed Cu‐doped NiO hole selective interlayer.24 The outstanding performance was attributed to an improved electrical conductivity of NiO. An applicability of Cu:NiOx with large band gap (E g) perovskite [CH3NH3PbI3−xBrx] solar cell has also been pointed out in this work. The PVSC devices using CH3NH3PbI3−xBrx with large E g encounter less potential loss and exhibit high photovoltage of 1.13–1.16 V. However, a relative low photocurrent of 8–12 mA cm−2 was obtained due to a less utilization of photons in the wavelength range from 670 to 780 nm. More recently, a remarkable efficiency of 17.3% was achieved on devices using pulsed laser deposited NiO.25 The (111)‐oriented nanostructured NiO film with good optical transparency plays a key role in the efficient extraction of holes and the prevention of electron leakage.

Optical manipulation has been successfully explored to improve light utilization efficiency in various photovoltaic devices, such as using folded device architecture, aperiodic dielectric stack, diffraction grating, and plasmon resonant metallic nanostructure.26 – 29 Among them, the introduction of metallic nanostructures as localized surface plasmon resonance (LPSR) into photovoltaic devices has been regarded as the most efficient and simple approach.30 Actually incorporation of Au@SiO2 core–shell nanoparticles into PVSCs has first reported in 2013.31 The authors showed the evidence for the reduced exciton binding energy in the perovskite absorber through photoluminescence study. It is known that the LSPR properties originate from collective oscillation of their electrons in response to optical excitation. However, in the previous report the photon absorption of metallic nanostructures can be negligible when considering the broad visible absorption spectrum and high adsorption coefficient of CH3NH3PbI3 active layer in devices.31 Therefore, the application of LSPR effect in perovskite devices has been long underestimated in this community. In line with this, the solar cells need to be structured so that light remains trapped inside to increase the photocurrent generation.

In this work, we report on an inverted CH3NH3PbI3−xBrx‐based PVSC employing a hybrid interfacial layer of “compact NiOx/meso‐Al2O3” in combination with nanostructured Au nanoparticles. The CH3NH3PbI3−xBrx absorbers with valence band (VB) ≈5.4 eV are specially selected to provide an optimized optical utilization, and well energy alignment with that of NiO to minimize energy loss. Most importantly, the optical band gap E g of CH3NH3PbI3−xBrx can be intentionally tuned wide enough, leaving a suitable spectrum window for the Au nanostructures. Therefore, an expected LSPR excitation in the range of 740–860 nm can be promoted by the resonant interaction between electromagnetic field of incident photons and surface charge oscillation of the Au nanorods (NRs). It should be noted that in the wavelength range, the CH3NH3PbI3−xBrx active layer does not absorb any photons. Therefore, we could intentionally investigate SPR effect for efficiency improvement of inverted PVSCs using Au nanoparticles. By imbedding a thin layer of Au NRs in the active layer of the PVSCs, the PCE was improved by a maximum value of 13.7%, which is attributed to enhanced local electric field originate from SPR effect.

2. Results and Discussion

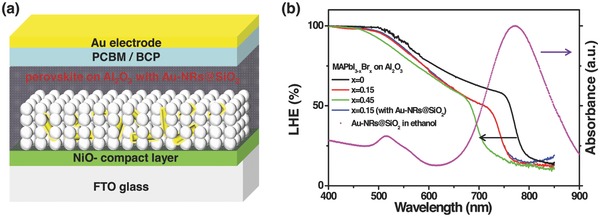

Figure 1 a depicts the typical inverted PVSC device configuration in this study. To incorporate metal nanoparticles into the perovskite active layer, ethanol solution containing Au@SiO2 was added to the Al2O3 colloid solution at a range of concentrations prior to porous alumina film deposition. The Au@SiO2 core–shell metal–dielectric nanoparticles were prepared with a three‐step synthesis process described elsewhere.32 X‐ray diffraction (XRD) analysis in Figure S1 (Supporting Information) exhibits a common pattern of bulk gold as well as a broad peak at around 25° corresponding to amorphous silica. Au@SiO2 nanoparticles with different AR can be obtained by adjusting either Au seeds or the content of the growth solution.33 The corresponding absorption characterization of these Au nanostructures is shown in Figure S2 (Supporting Information). Herein, Au@SiO2 nanorods with AR of 3.8 were chosen on account of its most red‐shift absorption peak (≈785 nm). As depicted in Figure 1b, the designed optical manipulation will take full advantage of the incident photons when CH3NH3PbI3− xBrx absorber and Au@SiO2 NRs are assembled in such a device. As most of photons in the overlap region could be cut off by light absorbers, a CH3NH3PbI3− xBrx perovskite with onset of absorption band from 786 nm (1.58 eV) to 704 nm (1.78 eV) has been synthesized and tested in this study. The light harvesting in the Au@SiO2 device is indistinguishable from the one without Au@SiO2 nanostructures due to a low loading of Au@SiO2 NRs (2.0 wt%) in the Al2O3 film.

Figure 1.

a) Illustration of device structure labeled with different components. b) Light harvesting efficiency (LHE) of CH3NH3PbI3−xBrx absorber (with different Br content) deposited on the same thickness of compact‐NiO/meso‐Al2O3 layer and UV–visible spectroscopy in ethanol for Au@SiO2 NRs with AR of 3.8. The LHE of CH3NH3PbI3−xBrx coated compact‐NiO/meso‐Al2O3 layer with Au@SiO2 NRs is also presented.

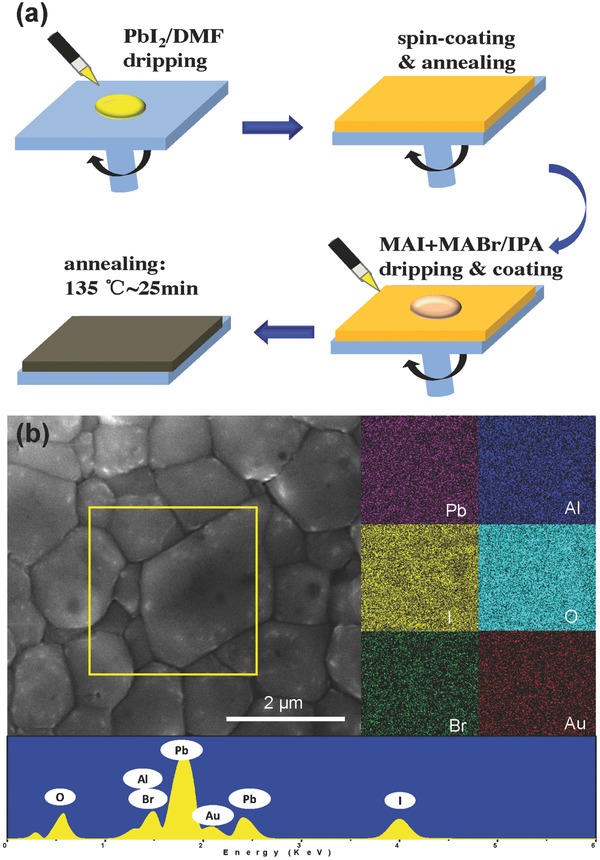

The CH3NH3PbI3− xBrx absorber was deposited by spun stacking of double layers of PbI2 and CH3NH3I+CH3NH3Br as illustrated in Figure 2 a. Details of the perovskite film preparation procedure can be found in the Experimental Section. Figure 2b shows the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) surface image of as‐prepared CH3NH3PbI3− xBrx film on the compact‐NiO/meso‐Al2O3 layer. The grain size increases fast to ≈1 μm in a 25 min annealing process. It has been reported that the big grain size CH3NH3PbI3− xBrx has less inner grain boundaries, which is benefited for reduction of charge recombination.34, 35 The EDX mapping result shows that “Au,” “Br,” and “I” elements are homogeneously distributed in the meso‐Al2O3 layer (Figure 2b), reflecting a good evidence of the existence of Au NPs and CH3NH3PbI3− xBrx materials.

Figure 2.

a) Schematics of the preparation approach to CH3NH3PbI3−xBrx perovskite film. b) Top view SEM image of CH3NH3PbI3−xBrx coated meso‐Al2O3 film with Au‐NRs and EDX mapping results of the yellow square region.

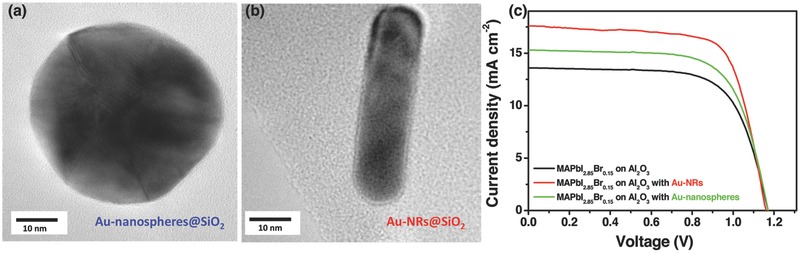

The evaluation of validity and rationality of our strategy on optical manipulation was first carried out with consideration of (1) Au NRs with various AR values, and (2) CH3NH3PbI3−xBrx with different Br contents. The absorption spectra of CH3NH3PbI3− xBrx absorber can be controlled through tuning CH3NH3I/CH3NH3Br molar ratio during the two‐step spin‐coating process. The used Au nanospheres with diameter of 41 nm (AR = 1, Figure 3 a) and Au‐NRs of about 42 nm length and 11 nm width (AR = 3.8, Figure 3b) were coated with an approximate 1–2 nm SiO2 shell. The absorption peaks are observed at ≈541 and ≈785 nm for the two Au nanostructure samples in ethanol (Figure S2, Supporting Information), respectively. After adding Au‐nanosphere (AR = 1) into the meso‐Al2O3 film, the photocurrent was increased by 12% from 13.6 to 15.3 mA cm−2 for the CH3NH3PbI3− xBrx (x = 0.15)‐based perovskite device. Keeping the same concentration of the Au additives, the device with Au‐NRs (AR = 3.8) showed even higher photocurrent of 17.5 mA cm−2 (Figure 3c). Compared to that of Au‐NRs, the J sc enhancement of perovskite devices with Au‐nanospheres has been suppressed, mainly due to an optical trapping competition raised from high extinction coefficient CH3NH3PbI3− xBrx (x = 0.15) absorber around 541 nm (Figure 1b).

Figure 3.

TEM images of the synthesized core–shell SiO2 coated a) Au‐nanospheres@SiO2 (AR = 1) and b) Au@SiO2 NRs (AR = 3.8). c) Photocurrent–voltage characterization of CH3NH3PbI2.85B0.15‐based PVSCs with and without Au nanostructures.

The photovoltaic performance for devices using compact‐NiO/meso‐Al2O3 with/without Au@SiO2 NRs (AR = 3.8)/CH3NH3PbI3− xBrx/[6,6]‐phenyl C61‐butyric acid methyl ester (PCBM)/bathocuproine (BCP)/Au configuration by varying Br content in perovskite was further investigated (Figure S3, Supporting Information). Indeed, as expected, the perovskite devices in presence of Br component exhibited higher V OC than the pristine CH3NH3PbI3‐based counterparts (Figure S3b, Supporting Information), confirming superior energy level alignment between CH3NH3PbI3− xBrx and NiO. The photocurrent of PVSC devices with adding Au@SiO2 NRs was higher than the control devices (Figure S3a, Supporting Information), which originates from the reutilization of photon in longer wavelength region around 785 nm. Increasing the Br portion in the CH3NH3PbI3− xBrx decreases the device's photocurrent. The decrease of photocurrent in the Br portion of x = 0–0.45 was accompanied by an augmentation of the V OC compensating the decrease in the fill factor. As a result, the overall power conversion efficiency reaches a maximum value of 13.5% at x = 0.15 over 15 piece of devices. The statistical data for device performance are shown in Figure S3a (Supporting Information). Therefore, the CH3NH3PbI2.85Br0.15 absorber in combination with Au@SiO2 NRs (AR = 3.8) takes the most advantage of the optical manipulation design. The work function analysis by photoelectron spectroscopy for the spin‐coated CH3NH3PbI3− xBrx perovskite film in line with the cell energy levels are depicted in Figure S4 (Supporting Information).

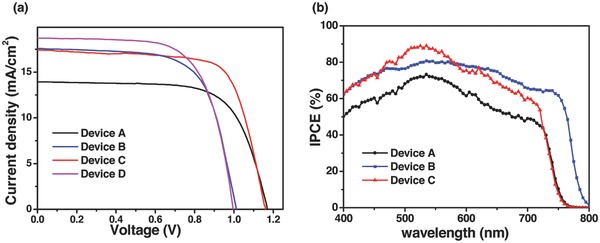

Some photovoltaic experiments were conducted to evaluate the performance of devices by varying the concentration of Au nanoparticles. It was found that the Au NRs concentration played a vital role on the devices performance. Figure S5 (Supporting Information) presents the photovoltaic parameters for the CH3NH3PbI2.85Br0.15‐based perovskite device as the concentration of Au@SiO2 NRs (AR = 3.8) varies from 0 to 4.2 wt%. The introduction of Au@SiO2 NRs results in an increased photocurrent, reaching a maximum value of 17.4 mA cm−2 at 2.0 wt% of Au@SiO2 NRs. The V OC is remarkably kept similar for various devices (Figure S5b, Supporting Information). Figure 4 a compares the photocurrent density–voltage (J–V) curves of the CH3NH3PbI3 or CH3NH3PbI2.85Br0.15 based PVSC devices W/O 2.0 wt% incorporation of Au@SiO2 NRs within the same thickness meso‐Al2O3 film. The photovoltaic parameters are tabulated in Table 1 . Device A (with Al2O3‐only using CH3NH3PbI2.85Br0.15) exhibits the PCE of 10.7% with a J SC of 13.9 mA cm−2, a V OC of 1.17 V, and a fill factor of 0.66. The replacement of CH3NH3PbI2.85Br0.15 with CH3NH3PbI3 results in a significant increase in J SC, achieving a PCE of 11.3% for device B. The addition of Au@SiO2 NRs in devices C and D result in a significant increase in J SC. Device C with compact‐NiO/meso‐Al2O3 with Au@SiO2 NRs/CH3NH3PbI2.85Br0.15/PCBM/BCP/Au configuration showed the highest PCE of 13.7% with a V OC of 1.16 V, a J SC of 17.4 mA cm−2, and a fill factor of 0.68. Devices A and C show higher V OC s compared to devices B and D, indicating CH3NH3PbI3− xBrx has better energy alignment with the deep VB of NiO. Considering the similar configuration in the four devices, the augmented output photovoltage and current could be contributed to the synergy effect from Au@SiO2 NRs and CH3NH3PbI2.85Br0.15 absorber. Figure 4b presents the incident photon‐to‐current conversion efficiency (IPCE) for the corresponding devices. Even though the difference of light harvesting capability can be ignorable for the CH3NH3PbI2.85Br0.15‐based devices with and without Au NRs (Figure 1b), an enhanced photocurrent was unambiguously observed for the former. We conclude that the photocurrent improvement is caused by the LSPR effect of Au@SiO2 NRs, rather than the scattering effect from metal nanoparticles.

Figure 4.

a) Representative J–V curves for devices using Al2O3‐only (devices A and B) and Al2O3 film incorporated with Au@SiO2 NRs (devices C and D) with MAPbI2.85Br0.15 (devices A and C) or MAPbI3 (devices B and D) absorbers measured under AM1.5 simulated sunlight (100 mW cm−2 irradiance). b) IPCE spectra of corresponding devices. MA: CH3NH3 + cation.

Table 1.

Photovoltaic parameters of the compact‐NiO/meso‐Al2O3/CH3NH3PbI3− xBrx (x = 0 and x = 0.15)/PCBM/BCP/Au configuration inverted PVSCs, with/without 2.0 wt% incorporation of Au@SiO2 NPs

| Device architecture | V oc [V] | J sc [mA cm−2] | FF | PCE [%] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Device A | CH3NH3PbI2.85Br0.15 on Al2O3 | 1.17 | 13.9 | 0.66 | 10.7 |

| Device B | CH3NH3PbI3 on Al2O3 | 1.01 | 17.2 | 0.65 | 11.3 |

| Device C | CH3NH3PbI2.85Br0.15 on Al2O3 with Au@SiO2 NRs | 1.16 | 17.4 | 0.68 | 13.7 |

| Device D | CH3NH3PbI3 on Al2O3 with Au@SiO2 NRs | 0.99 | 18.7 | 0.66 | 12.2 |

| Device E | CH3NH3PbI2.85Br0.15 on Al2O3 with Au@SiO2 nanospheres | 1.16 | 15.3 | 0.65 | 11.5 |

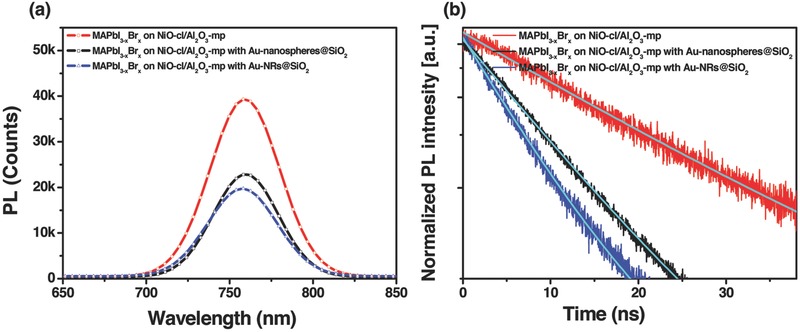

Photoluminescence (PL) measurements on CH3NH3PbI2.85Br0.15 coated NiO/meso‐Al2O3 layer with and without the addition of Au @SiO2 nanoparticles (AR = 1 and 3.8) are performed to further probe the influence of the LSPR effect. The excitation wavelength was set at 435 nm in order to avoid any external electromagnetic radiation on Au nanoparticles (absorption peak at 530 nm for that with AR of 1, and absorption peak of 785 nm with AR of 3.8). Figure 5 a shows time‐integrated PL spectrum at room temperature, revealing a significant reduction in the signal for the samples incorporating Au NRs over six samples. Figure 5b shows the result of time‐resolved PL measurement at the emission peak (760 nm). An accelerated PL quenching was observed for the sample with the Au NRs. The time constant was evaluated to be 10.9 and 12.1 ns for the sample with Au nanoparticles of AR = 3.8 and AR = 1, respectively, indicating both of them play similar role during the charge separation process. A longer time constant of 24.7 ns was observed for the film without Au nanostructures. The enhanced PL quenching could be contributed from ionization of the excitons and enhanced charge separation, which is related to the LSPR effect of Au NRs.36, 37

Figure 5.

Photoluminescence study: a) Time‐integrated spectra and b) time‐resolved PL decays (detected at 760 nm) for MAPbI3−xBrx perovskite coated on meso‐Al2O3 film with and without incorporating Au‐nanospheres@SiO2 (AR = 1) or Au@SiO2 NRs (AR = 3.8).

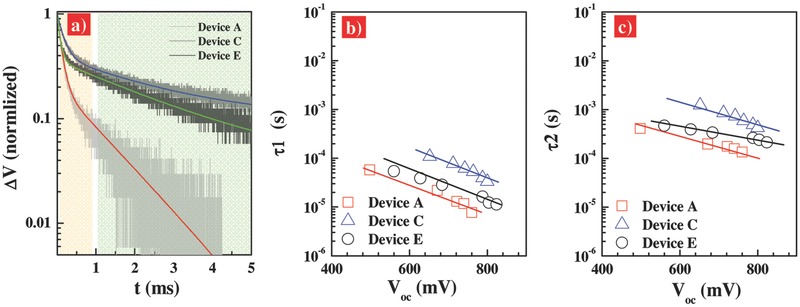

The interfacial charge‐recombination in the CH3NH3PbI2.85B0.15‐based PVSCs was further investigated with transient photovoltage decay (TPD) measurements, which is presented in Figure 6 a. This technique is widely employed for the determination of charge lifetimes (τn) in sensitized solar cells.38, 39 Figure S6 (Supporting Information) depicts the typical voltage transient dynamics for all devices responding to the light perturbation. The recombination kinetics in these inverted PVSCs are yet to be fully understood, however, we observed biphasic decays with double exponential functions (Figure 6a). The two time constants (τ1 and τ2) are suggestive of the presence of two distinguished populations of generated carriers and their recombination independently. Figure 6b,c presents the extracted charge lifetime by fitting photovoltage decay results as a function of the open‐circuit voltage for various devices. This result is different with that observed for dye‐sensitized solar cells.40, 41 The lifetime constant in the range of 0.1–10 ms depending on the sensitizers and electrolytes can be ascribed to the interfacial charge recombination between electrons in the dye‐covered TiO2 and holes in the redox mediators. Therefore, for the perovskite devices, the charge population bearing a short lifetime (τ1, in the range of microseconds in Figure 6b) might be attributable to the charge confined within the perovskite bulk layer recombining with defect traps or PCBM. And we associate the longer voltage decay component (τ2, in the range from 0.1 to 10 ms in Figure 6c) to the electrons recombining with holes in NiO near the perovskite/charge selective layer interface. An increased lifetime was observed when Au nanoparticles were used. This is contrast to the findings of LSPR effect in dye‐sensitized solar cell. A shorter interfacial charge recombination lifetime of about milliseconds was usually observed for the dye‐sensitized devices when the metallic nanostructures were incorporated.41 This observation was explained by a triggered interfacial charge recombination between the metallic nanoparticles and their neighbor mediators.42 Previous investigation on dye‐sensitized solar cells revealed that the augmented photocurrent could be contributed both from the scatter effect of metallic nanoparticles and/or the boosted charge separation efficiency when gold NRs was used.42 As shown in Table 1, there is about 3.5 mA cm−2 enhancement in the J SC for device C compared with device A. The charge lifetime for device A is about ten times longer than that of device C. Therefore, this result indicates that the augment in J SC for device A could be contributed to the longer lifetime. It is noted that, herein, the perovskite devices with Au @SiO2 NRs (AR = 3.8) show the longer charge lifetime than that of devices with Au nanosphere (AR = 1). A long charge lifetime guarantees effective charge collection efficiency, thus the device output photocurrent. This result indicates the aspect ratio of Au nanoparticles could play critical role in the photo‐induced enhanced dissociation of excitons. The similar PL quenching of the films with Au nanostructures with various ARs (Figure 5) indicates the same charge generation rate, however, the device C (with Au NRs) shows an order of magnitude higher in charge lifetime than the device E (with Au nanospheres).

Figure 6.

a) Transient photovoltage decay (TPD) data for device A, C in Table 1 and device E with compact‐NiO/meso‐Al2O3/CH3NH3PbI2.85Br0.15/PCBM/BCP/Au configuration with 2.0 wt% incorporation of Au‐nanospheres@SiO2, measured under 0.5% sun illumination. And charge recombination lifetime, b) τ1 and c) τ2, as a function of the open‐circuit voltage, derived from the double exponential fitting of TPD curves.

3. Conclusion

In summary, we demonstrated the incorporation of Au@SiO2 nanorod into the inverted CH3NH3PbI2.85Br0.15 perovskite solar cells could significantly increase the device photocurrent, which could be contributed to the LSPR excitation in the range of 740–860 nm by the resonant interaction. An increased interfacial charge recombination lifetime in line with effective charge collection was further observed in the inverted CH3NH3PbI2.85Br0.15 perovskite solar cells containing Au nanorods. As a result, a considerably higher PCE of up to 13.7% was achieved. This optical manipulation strategy can be extendable to a broad community of thin film solar cells.

4. Experimental Section

Materials and Sample Preparation: All solvents and reagents, unless otherwise stated, were of analytically pure quality and used as received. PbI2 (99%), Al2O3 nanoparticles dispersion in isopropanol (<50 nm, 20 wt%), nickel acetylacetonate (95%), super dehydrated solvents of dimethyl formamide (DMF), isopropanol, and chlorobenzene were all purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Synthesis process of Au@SiO2 NPs can be referred to the Supporting Information.

Fabrication of CH3NH3PbI3−xBrx‐Based Perovskite Solar Cells: The ethylammonium lead iodide (CH3NH3PbI3) was prepared according to a previous work.22 CH3NH3PbI3− xBrx was deposited with a modified two‐step spin‐coating method.13 First, the p‐type selective interlayer, NiOx was deposited onto the precleaned and prepatterned transparent glass/fluorine‐doped tin oxide (FTO) coated glasses (Pilkington TEC 15 Ω −1) with a spray pyrolysis method. For transparent meso‐Al2O3 film preparation, 2.0 g Al2O3 nanoparticles dispersion in isopropanol (20 wt%) was added to 12.0 g α‐terpinol and 2.0 g ethanol solution of ethyl cellulose (10 wt%), the mixture was then treated in ultrasonic bath for 30 min and string for another 30 min to form a homogenous paste. 5 wt% Au@SiO2 NRs ethanol solution were mixed with different concentrations (from 0 to 4.2 wt% of Au@SiO2 NRs/Al2O3). The paste was subsequently spin‐coated and sintered at 550 °C for 30 min. A concentration of 460 mg mL−1 of PbI2 in DMF solution was then spin‐coated onto NiO/Al2O3 layer (3000 rpm for 30 s). MAI and MABr (MA: CH3NH3 +) were mixed with different MAI/MABr molar ratio in 2‐propanol at 0.3 m and then spin‐coated on dry PbI2 layer at room temperature. The formation of continuous, compact CH3NH3PbI3− xBrx perovskite films will be completed after annealing at 100 °C for 25 min. The surface morphology of CH3NH3PbI3− xBrx film was characterized by the cross section images of SEM. The PCBM (≈60 nm) and BCP (<10 nm) were spin‐coated inside an argon‐filled glove box. Au layer (65 nm) was thermally deposited on the substrate inside a vacuum chamber (10−6 Torr). The active area of the device is 0.16 cm2.

Characterization: A xenon light source solar simulator (450 W, Oriel, model 9119) with AM 1.5G filter (Oriel, model 91192) was used to give an irradiance of 100 mW cm−2 at the surface of the solar cells. Various irradiance intensities from 0.01 to 1.0 sun can be provided with neutral wire mesh 50 attenuators, and the light intensity was calibrated with a standard silicon solar cell. The current–voltage characteristics of the devices under these conditions were obtained by applying external potential bias to the devices and measuring the generated photocurrent with a Keithley model 2400 digital source meter. The J–V characteristics were recorded by reverse scan or forward scan with a scan rate of 50 mV s−1. A similar data acquisition system was used to control the IPCE measurement. SEM images were obtained using FEI Nova NanoSEM 450. XRD results were acquired using Phillips X'Pert PRO. The time‐resolved and steady‐state PL measurements were recorded with Edinburgh instruments (FLSP920 spectrometers). The excitation light source was a femtosecond laser centered at 435 nm, operated at a power of 10 mW.

Transient photovoltage decay measurements were performed on all the cells using a ring of red LED (Lumiled) controlled by a fast solid‐state switch. The pulse widths were 2 ms. An array of InGaN diodes (Lumiled) supplied the white bias light, transients were measured at different white light intensities via tuning the voltage applied to the bias diodes. The voltage output was recorded on an oscilloscope directly connected with the cells.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the Director Fund of the Wuhan National Laboratory for Optoelectronics (WNLO), the 973 Program of China (Grant Nos. 2014CB643506 and 2013CB922104) is gratefully acknowledged. The authors thank the Analytical and Testing Centre at the Huazhong University of Science and Technology (HUST) for performing characterization of various samples.

Cui J., Chen C., Han J., Cao K., Zhang W., Shen Y., Wang M. (2016). Surface Plasmon Resonance Effect in Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Sci., 3: 1500312. doi: 10.1002/advs.201500312

References

- 1. Kojima A., Teshima K., Shirai Y., Miyasaka T., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 6050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee M., Teuscher J., Miyasaka T., Murakami T., Snaith H., Science 2012, 338, 643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Malinkiewicz O., Yella A., Lee Y., Espallargas G., Graetzel M., Nazeeruddin M., Bolink H., Nat. Photonics 2014, 8, 128. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhou H., Chen Q., Li G., Luo S., Song T., Duan H., Hong Z., You J., Liu Y., Yang Y., Science 2014, 345, 542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yang W., Noh J., Jeon N., Kim Y., Ryu S., Seo J., Seok S., Science 2015, 348, 1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stranks S., Eperon G., Grancini G., Menelaou C., Alcocer M., Leijtens T., Herz L., Petrozza A., Snaith H., Science 2013, 342, 341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Xing G., Mathews N., Sun S., Lim S., Lam Y., Grätzel M., Mhaisalkar S., Sum T., Science 2013, 342, 344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xu X., Zhang Z., Cao K., Cui J., Lu J., Zeng X., Shen Y., Wang M., ChemSusChem 2014, 7, 3088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu M., Johnston M., Snaith H., Nature 2013, 501, 395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Docampo P., Ball J., Darwich M., Eperon G., Snaith H., Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jeng J., Chen K., Chiang T., Lin P., Tsai T., Chang Y., Guo T., Chen P., Wen T., Hsu Y., Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 4107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang Q., Shao Y., Dong Q., Xiao Z., Yuan Y., Huang J., Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 2359. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xiao Z., Bi C., Shao Y., Dong Q., Wang Q., Yuan Y., Wang C., Gao Y., Huang J., Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 2619. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Snaith H., Abate A., Ball J., Eperon G., Leijtens T., Noel N., Stranks S., Wang J., Wojciechowski K., Zhang W., J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shao Y., Xiao Z., Bi C., Yuan Y., Huang J., Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xu J., Buin A., Ip A. H., Li W., Voznyy O., Comin R., Yuan M., Jeon S., Ning Z., McDowell J. J., Kanjanaboos P., Sun J., Lan X., Quan L., Kim D., Hill I., Maksymovych P., Sargent E. H., Nat. Commun. 2014, 6, 7081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xiao Z., Dong Q., Bi C., Shao Y., Yuan Y., Huang J., Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 6503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang Q., Bi C., Huang J., Nano Energy 2015, 15, 275. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Irwin M., Buchholz D., Hains A., Chang R., Marks T., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2783. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Manders J., Tsang S., Hartel M., Lai T., Chen S., Amb C., Reynolds J., So F., Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 2993. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Alemu G., Li J., Cui J., Xu X., Zhang B., Cao K., Shen Y., Cheng Y., Wang M., J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 9216. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cui J., Meng F., Zhang H., Cao K., Yuan H., Cheng Y., Huang F., Wang M., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 22862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen W., Wu Y., Liu J., Qin C., Yang X., Islam A., Cheng Y., Han L., Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 629. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim J., Liang P., Williams S., Cho N., Chueh C., Glaz M., Ginger D., Jen A., Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Park J., Seo J., Park S., Shin S., Kim Y., Jeon N., Shin H.‐W., Ahn T., Noh J., Yoon S., Hwang C., Il Seok S., Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 4013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wong W., Wang X., He Z., Djurisic A., Yip C., Cheung K., Wang H., Mak C., Chan W., Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee J., Park J., Kim J., Lee D., Cho K., Org. Electron. 2009, 10, 416. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xu M., Zhu X., Shi X., Liang J., Jin Y., Wang Z., Liao L., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Atwater H., Polman A., Nat. Mater. 2010, 9, 205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jankovic V., Yang Y., You J., Dou L., Liu Y., Cheung P., Chang J., Yang Y., ACS Nano 2013, 7, 3815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang W., Saliba M., Stranks S., Sun Y., Shi X., Wiesner U., Snaith H., Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 4505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nikoobakht B., El‐Sayed M., Chem. Mater. 2003, 15, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang Z., Cui J., Li J., Cao K., Yuan S., Cheng Y., Wang M., Mater. Sci. Eng., B 2015, 199, 1. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nie W., Tsai H., Asadpour R., Blancon J., Neukirch A., Gupta G., Crochet J., Chhowalla M., Tretiak S., Alam M., Wang H., Mohite A., Science 2015, 347, 522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cao K., Cui J., Zhang H., Li H., Song J., Shen Y. , Cheng Y., Wang M., J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 9116. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Achermann M., J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 2837. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu W., Lin F., Yang Y., Huang C., Gwo S., Huanga M., Huang J., Nanoscale 2013, 5, 7953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. O'Regan B., Durrant J., Sommeling P., Bakker N., J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 14001. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Regan O', Lenzmann F., J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 4342. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang M., Chamberland N., Breau L., Moser J., Humphry‐Baker R., Marsan B., Zakeeruddin S., Grätzel M., Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang M., Moon S., Xu M., Chittibabu K., Wang P., Cevey‐Ha N., Humphry‐Baker R., Zakeeruddin S., Grätzel M., Small 2010, 6, 319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xu X., Cui J., Han J., Zhang J., Zhang Y., Luan L., Alemu G., Wang Z., Shen Y., Xiong D., Chen W., Wei Z., Yang S., Hu B., Cheng Y., Wang M., Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 3961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary