Abstract

Purpose

The global Phase III MPACT trial demonstrated superior efficacy of nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine over gemcitabine alone as first-line treatment for metastatic pancreatic cancer. Region was a randomization stratification factor in the MPACT trial. This subgroup analysis of MPACT examined efficacy and safety of patients treated in Western Europe.

Patients and methods

Patients received nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine or gemcitabine alone as first-line treatment for metastatic pancreatic cancer as previously described. A total of 76 patients were included in this analysis (n=38 for each arm).

Results

Differences between the overall Western European cohort and the intention-to-treat population included lower percentages of male patients (46% and 58%, respectively) and patients with biliary stents (8% and 17%), and higher percentages of patients with Karnofsky performance status of 90–100 (78% and 60%) and primary tumors in the body of the pancreas (48% and 31%). The median overall survival was 10.7 months with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine vs 6.9 months with gemcitabine alone (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.82 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.48–1.40]; P=0.471). Median progression-free survival was 5.3 vs 3.7 months, respectively (HR: 0.70 [95% CI: 0.37–1.33]; P=0.277). The independently assessed overall response rate was 18% vs 5% (response rate ratio, 3.50 [95% CI: 0.78–15.78]; P=0.076). The most common grade ≥3 adverse events with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine and gemcitabine alone were neutropenia (46% vs 33%, respectively), leukopenia (35% vs 19%), anemia (22% vs 0%), asthenia (21% vs 6%), thrombocytopenia (14% vs 3%), and peripheral neuropathy (13% vs 3%).

Conclusion

Although a statistically significant difference between the treatment arms was not reached for efficacy endpoints, this study does report treatment benefit and a manageable safety profile associated with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine in patients treated in Western Europe with metastatic pancreatic cancer.

Keywords: metastatic pancreatic cancer, nab-paclitaxel, gemcitabine, Western Europe, MPACT

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death in Europe, with mortality nearly equaling incidence.1,2 The overall 5-year survival rate for patients with pancreatic cancer is approximately 7%–8%.3,4 Fewer than 20% of patients have resectable tumors at the time of diagnosis, and most patients present with metastatic disease.5 The major objectives of treating patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer are to palliate symptoms, control disease progression, and increase survival time.6,7

Three Phase III trials have demonstrated longer overall survival (OS) with investigational treatment regimens vs gemcitabine monotherapy as first-line treatment for advanced pancreatic cancer.8–10 The combination of erlotinib plus gemcitabine achieved a significant, albeit modest, increase in OS vs gemcitabine in a global study of patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer.10 The regimen consisting of 5-fluorouracil, folinic acid (leucovorin), irinotecan, and oxaliplatin (FOLFIRINOX) demonstrated greater efficacy than gemcitabine in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer treated exclusively in France.9 The Phase III MPACT trial was a global study that demonstrated better efficacy of nab-paclitaxel (Abraxane, Celgene Corporation, Summit, NJ, USA) plus gemcitabine than gemcitabine alone. An updated OS analysis demonstrated a >2-month difference in median OS with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine vs gemcitabine alone (median, 8.7 vs 6.6 months; hazard ratio [HR]: 0.72 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.62–0.83]; P<0.001) in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population.11

The MPACT trial (N=861) enrolled patients at 151 community and academic centers in 11 countries in North America, Eastern Europe, Western Europe, and Australia. Geographic region was a randomization stratification factor, which is common in global trials to control for differences in patient populations and health care systems. The primary analysis of OS demonstrated that median OS varied by region. However, at the time of that analysis, median OS values in Western Europe were not mature (not reached with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine vs 6.9 months with gemcitabine alone; HR: 0.72 [95% CI: 0.35–1.47]).8,12 There are also scant published data on the efficacy and safety of nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine, a commonly used standard of care, in the Western European patient population. The objective of the current study was to examine the efficacy and safety of nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine vs gemcitabine alone in the Western European cohort of the MPACT trial.

Patients and methods

The MPACT trial design was previously described.8 Key details are provided below. The MPACT trial was approved by the independent ethics committee at each participating institution and was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation E6 requirements for Good Clinical Practice and with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The complete list of institutional review board and independent ethics committee locations has been published elsewhere.13 All patients provided written informed consent before initiation of the study.

Patients

Adults with Karnofsky performance status (KPS) ≥70 and measurable stage IV metastatic pancreatic cancer based on Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.0 were enrolled. Exclusion criteria included prior treatment with chemotherapy for metastatic disease or prior adjuvant systemic chemotherapy, including gemcitabine. After the closure of the MPACT trial (NCT00844649) in 2013, an observational extension study was initiated to gather additional survival information on patients who were still alive (NCT02021500). The data collected from the extension study are included in this post hoc evaluation.

Treatments

Patients were randomized 1:1 to intravenous nab-paclitaxel 125 mg/m2 plus intravenous gemcitabine 1,000 mg/m2 for the first 3 of 4 weeks or intravenous gemcitabine monotherapy 1,000 mg/m2 for the first 7 of 8 weeks (cycle 1) followed by the first 3 of 4 weeks (cycles 2 onward). Randomization was stratified by geographic region, KPS, and presence of liver metastases. Patients were treated until disease progression or an unacceptable level of adverse events.

Assessments

Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scans were performed every 8 weeks. Lesion size and overall response rate (ORR) were evaluated by RECIST version 1.0. Safety was graded by the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 3.0.

Statistics

Safety and efficacy analyses were performed on the Western European cohort population only. The primary efficacy endpoint was OS, which was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method. Secondary endpoints were progression-free survival (PFS) and ORR. The effect of treatment on OS was determined by log-rank testing stratified by preestablished criteria (KPS, geographic region, and presence of liver metastases). The data cutoff for this analysis of the MPACT trial was May 9, 2013. All statistical tests were two-sided and performed with SAS v9.2.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the Western European cohort (n=76) were similar between patients in the nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine arm and those in the gemcitabine-alone arm (Table 1). The Western European cohort comprised patients who received treatment in the following countries: Italy (n=37), Spain (n=16), Germany (n=8), France (n=6), Austria (n=6), and Belgium (n=3). Differences between the overall Western European cohort and the ITT population included a lower percentages of males (46% and 58%, respectively) and patients with biliary stents (8% and 17%) and a higher percentages of patients with KPS 90–100 (78% and 60%) and primary tumors in the body of the pancreas (48% and 31%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the Western European cohort

| Characteristic |

nab-P + Gem (n=38) |

Gem (n=38) |

All patients in Western Europe (n=76) | ITT population (N=861)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range), years | 59.5 (37–77) | 66.0 (42–80) | 63.0 (37–80) | 63.0 (27–88) |

| ≥65 years, % | 29 | 61 | 45 | 42 |

| Male, % | 53 | 39 | 46 | 58 |

| KPS, % | ||||

| 90–100 | 74 | 82 | 78 | 60 |

| 70–80 | 24 | 18 | 21 | 40 |

| Primary tumor location, % | ||||

| Head | 39 | 27a | 33 | 43 |

| Body | 47 | 49a | 48 | 31 |

| Tail | 13 | 24a | 19 | 25 |

| Site(s) of metastasis, % | ||||

| Liver | 87 | 84 | 86 | 84 |

| Lung | 24 | 45 | 34 | 39 |

| No of metastatic sites, % | ||||

| 1 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 |

| 2 | 53 | 47 | 50 | 47 |

| ≥3 | 39 | 45 | 42 | 46 |

| Previous Whipple, % | 0 | 5 | 3 | 7 |

| Biliary stent, % | 8 | 8 | 8 | 17 |

Notes:

Evaluable n=37.

From N Engl J Med, Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, et al, Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine, 69, 1691–1703. Copyright © (2013) Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission from Massachusetts Medical Society.8

Abbreviations: Gem, gemcitabine; ITT, intention-to-treat; KPS, Karnofsky performance status; nab-P, nab-paclitaxel.

Efficacy

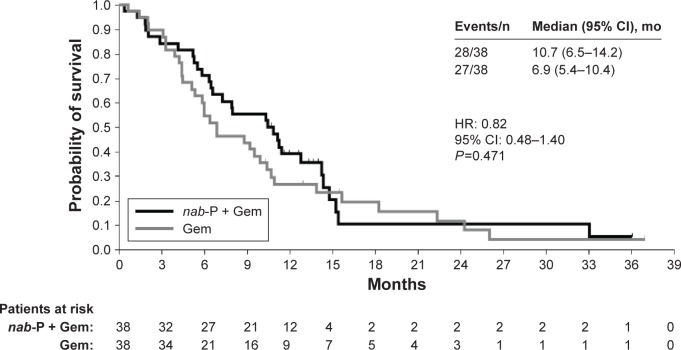

Median OS was 3.8 months longer in the nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine arm than in the gemcitabine monotherapy arm (10.7 vs 6.9 months; HR: 0.82 [95% CI: 0.48–1.40]; P=0.471; Figure 1). The survival curves for the 2 Western European treatment arms separated at approximately 4 months, with the initial trend supporting greater benefit from the combination regimen. In addition, the 1-year OS rate favored nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine over gemcitabine alone (39% vs 27%).

Figure 1.

Overall survival in the Western European cohort.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; Gem, gemcitabine; HR, hazard ratio; mo, month; nab-P, nab-paclitaxel.

Both PFS and ORR by independent review were numerically (but not significantly) better with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine vs gemcitabine alone. Median PFS was 5.3 vs 3.7 months, respectively (HR: 0.70 [95% CI: 0.37–1.33]; P=0.277). The independently assessed ORR was 18% with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine vs 5% with gemcitabine alone (response rate ratio, 3.50 [95% CI: 0.78–15.78]; P=0.076).

Subsequent therapies

Second-line therapies were administered to 20 patients who received first-line nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine and 22 patients who received gemcitabine alone (Table 2). Fluoropyrimidine (5-fluorouracil or capecitabine)-containing second-line regimens were most common (95% of patients who received second-line therapy after first-line nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine vs 86% of patients who received second-line therapy after first-line gemcitabine). Among patients who received second-line therapy, FOLFIRINOX (full-dose or modified) was administered to 5% of those who received first-line nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine and 9% of those who received first-line gemcitabine.

Table 2.

Second-line therapy in the treated population of the Western European cohort

| Regimen, n (%) |

nab-P + Gem (n=39) |

Gem (n=36) |

|---|---|---|

| Any second-line therapy | 20 (51) | 22 (61) |

| Fluoropyrimidine containing | 19 (95) | 19 (86) |

| FOLFOX/OFF | 5 (25) | 5 (23) |

| FOLFIRINOX | 1 (5) | 2 (9) |

| Other than fluoropyrimidine containing | 1 (5) | 3 (14) |

Abbreviations: FOLFIRINOX, 5-fluorouracil, folinic acid (leucovorin), irinotecan, and oxaliplatin; FOLFOX, folinic acid (leucovorin), fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin; Gem, gemcitabine; nab-P, nab-paclitaxel; OFF, oxaliplatin, folinic acid, and 5-fluorouracil.

Safety

The most common grade ≥3 hematologic toxicities in the nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine and gemcitabine-alone arms of the Western European cohort were neutropenia (46% vs 33%, respectively), leukopenia (35% vs 19%), anemia (22% vs 0%), and thrombocytopenia (14% vs 3%; Table 3). Growth factors were administered to 14 patients (36%) in the nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine arm and four patients (11%) in the gemcitabine-alone arm. Notably, no patients in either treatment arm experienced febrile neutropenia.

Table 3.

Safety in the treated population of the Western European cohort

| Safety, n (%) |

nab-P + Gem (n=39)a |

Gem (n=36) |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with ≥1 AE leading to death | 2 (5) | 2 (6) |

| Grade ≥3 hematologic AEs in >10% of patients in either armb | (n=37) | |

| Neutropenia | 17 (46) | 12 (33) |

| Leukopenia | 13 (35) | 7 (19) |

| Anemia | 8 (22) | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 5 (14) | 1 (3) |

| Grade ≥3 nonhematologic AEs in >10% of patients in either armc | ||

| Asthenia | 8 (21) | 2 (6) |

| Peripheral neuropathyd | 5 (13) | 1 (3) |

| Alopecia | 4 (10) | 0 |

Notes:

One patient was randomized to the Gem-only arm but received nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine;

Assessment of the event was made on the basis of laboratory values;

Assessment of the event was made on the basis of investigator assessment of treatment-related AEs;

Peripheral neuropathy was reported on the basis of groupings of preferred terms, defined by standardized queries in the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities.

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; Gem, gemcitabine; nab-P, nab-paclitaxel.

The most common grade ≥3 nonhematologic adverse events were asthenia, alopecia, and peripheral neuropathy. Grade 3 peripheral neuropathy was more common with the combination regimen than with gemcitabine monotherapy (13% vs 3%). Among the five patients in the combination arm who experienced peripheral neuropathy, the median time to onset was 155 days (range, 113–190 days), and three of the five patients improved to grade 1 or better (median time to improvement to grade ≤1 peripheral neuropathy was 26 days; range, 15–78 days).

Discussion

The results from this regional analysis of the MPACT trial are consistent with those of the overall trial population.8,11 In this analysis of patients in Western Europe with metastatic pancreatic cancer, a survival difference of nearly 4 months was observed between the nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine and gemcitabine-alone arms; however, this difference did not reach statistical significance. The median PFS of 5.3 vs 3.7 months for nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine vs gemcitabine alone corresponded closely with those of the overall population (5.5 vs 3.7 months, respectively).8 The toxicities within the Western European cohort were generally similar to those reported for the overall treated population, except for grade ≥3 anemia, which was reported in 13% of patients in the nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine arm and 12% of patients in the gemcitabine-alone arm in the overall population.8 Taken together, these data indicate that nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine has a manageable safety profile and is an efficacious first-line option in Western European patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer.

The longer survival associated with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine use among patients in Western Europe compared with the ITT population is intriguing. Possible explanations include a better performance status at baseline (78% vs 60% of patients in the Western European cohort and ITT population, respectively, had a KPS of 90–100) and greater secondary therapy use among patients in Western Europe (56%) compared with the ITT population (40%).14 The feasibility and benefit of first-line nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine for the treatment of advanced pancreatic cancer among patients in Europe are in agreement with outcomes reported elsewhere.15 A retrospective analysis of several centers in Italy revealed that the majority of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer (122 [55%]; total N=221 patients) treated with first-line nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine were able to receive a second line of therapy, and the median OS among these patients was 13.5 months (95% CI: 12.66–14.34).

Limitations

The size of the analyzed population in this analysis may limit the ability to draw definitive conclusions from the results. For example, the small number of patients in each arm likely contributed to some imbalances in baseline characteristics, including a higher percentage of patients ≥65 years of age in the gemcitabine arm. Further, although efficacy results appeared to be better in the nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine arm, treatment differences in most endpoints were not statistically significant, likely due to small patient numbers.

Conclusion

This subanalysis of the MPACT trial showed evidence that patients in Western Europe with metastatic pancreatic cancer may benefit from nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine, which is consistent with the findings observed in the ITT population. The median OS with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine in the Western European cohort is 2 months longer than that in the ITT population (10.7 and 8.7 months, respectively), while the results for the gemcitabine-alone cohort were similar (6.9 and 6.6 months, respectively).11 No new safety concerns were noted in the Western European cohort relative to those previously reported for the ITT population. The consistency of the findings between the Western European cohort and the ITT population is encouraging and supports the overall implications, despite the limitation of a small sample size that likely prevented statistically significant differences in efficacy between the two treatment arms.

Acknowledgments

Sponsorship for this study and article processing charges was funded by Celgene Corporation, Summit, NJ, USA. Editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript was provided by John McGuire, PhD, of MediTech Media, and support for this assistance was funded by Celgene Corporation. The authors were fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions for this manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Josep Tabernero: consultant or advisory role, Amgen, Boehringer, BMS, Celgene, Genentech, Imclone, Lilly, Merck KGaA, Millennium, Novartis, Onyx, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi; honoraria, Amgen, Merck KGaA, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi.

Volker Kunzmann: consultant or advisory role and research funding, Celgene.

Werner Scheithauer: consultant or advisory role and honoraria, Celgene.

Michele Reni: consultant or advisory role, honoraria, research funding, Celgene.

Jack Shiansong Li, Stefano Ferrara, Kamel Djazouli: employment, stock ownership, Celgene. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Malvezzi M, Bertuccio P, Levi F, La Vecchia C, Negri E. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2014. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(8):1650–1656. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization GLOBOCAN 2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality, and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012. [Accessed November 17, 2016]. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_population.aspx.

- 3.Lepage C, Capocaccia R, Hackl M, et al. Survival in patients with primary liver cancer, gallbladder and extrahepatic biliary tract cancer and pancreatic cancer in Europe 1999–2007: results of EUROCARE-5. Eur J Cancer. 2015 Sep 5; doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.07.034. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Pancreas Cancer. 2016. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/pancreas.html.

- 5.Ryan DP, Hong TS, Bardeesy N. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(22):2140–2141. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1412266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ducreux M, Cuhna AS, Caramella C, et al. Cancer of the pancreas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(Suppl 5):v56–v68. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. V1. 2016. [Accessed November 17, 2016]. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/pancreatic.pdf.

- 8.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(18):1691–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(19):1817–1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, et al. Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(15):1960–1966. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein D, El-Maraghi RH, Hammel P, et al. nab-Paclitaxel plus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer: long-term survival from a phase III trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(2):dju413. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tabernero J, Chiorean EG, Infante JR, et al. Prognostic factors of survival in a randomized phase III trial (MPACT) of weekly nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine alone in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Oncologist. 2015;20(2):143–150. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vogel A, Römmler-Zehrer J, Li JS, McGovern D, Romano A, Stahl M. Efficacy and safety profile of nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer treated to disease progression: a subanalysis from a phase 3 trial (MPACT) BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):817. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2798-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiorean EG, Von Hoff DD, Tabernero J, et al. Second-line therapy after nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine or after gemcitabine for patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2016;115(2):188–194. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giordano G, Febbraro A, Milella M, et al. Impact of second-line treatment (2L T) in advanced pancreatic cancer (APDAC) patients (pts) receiving first line nab-paclitaxel (nab-P) + gemcitabine (G): an Italian multicentre real life experience. J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts) 2016;34(Suppl) abstr 4124. [Google Scholar]