Abstract

Introduction

The attachment theory is widely used in order to explain anorexia nervosa origin, course and treatment response. Nevertheless, very little literature specifically investigated parental bonding in adolescents with anorexia, as well as the parents’ own bonding and intergenerational transmission within the family.

Purpose

This study aims to identify any specific pattern of parental bonding in families of adolescents newly diagnosed with restricting-type anorexia, comparing them to the families of the control group.

Patients and methods

A total of 168 participants, adolescents and parents (78 belonging to the anorexia group and 90 to the control one), rated the perceived parental styles on the parental bonding instrument. The latent class analysis allowed the exploration of a maternal bonding latent variable and a paternal one.

Results

The main findings showed that a careless and overcontrolling parental style was recalled by the patients’ parents, and in particular by the fathers. As far as the adolescents’ responses were concerned, patients with anorexia did not seem to express differently their parental bonding perception from participants of the control group.

Conclusion

Clinical implications driven from the results suggest that a therapeutic intervention working on how the parents’ own attachment representations influence current relationships may help to modify the actual family functioning and thus the outcome of patients with anorexia.

Keywords: restricting-type anorexia nervosa, adolescence, parental bonding instrument, inter-generational transmission, latent class analysis, care and overprotection

Introduction

To date, there is a wide literature focusing on the attachment theory1 as a possible framework for understanding anorexia nervosa origin, course and treatment response.2–4 Despite the increasing evidences of dysfunctional family relations and insecure style of attachment in eating-disordered patients,5–7 literature data are contradictory and limited by a wide variety of methodological approaches.8

To summarize the findings regarding attachment in eating disorders (EDs), it is worth noticing that insecure attachment (dismissing or preoccupied types) is frequent among patients with EDs: in particular, avoidant attachment tends to be more represented in patients with restricting anorexia, while patients with bulimia show a higher prevalence of attachment preoccupation.8 On the whole, patients with EDs often report problems with childhood family relationships,8 but the precise nature of the problems and the mechanism underlying their connection with EDs are rather unclear, since findings from scientific literature appear to be still inconclusive.3,8,9

Literature exploring the connection between EDs and early parent–child relations include studies based on the attachment theory as well as on the parental bonding construct.8,9 Both of the constructs provide information about the family relationships, as subjectively perceived by an individual.10 However, if the attachment construct refers prevalently to how the child responds to parental behaviors, the parental bonding construct instead addresses mainly the representation of the parents’ contribution to the parent–child relation.11 Several studies dealt with the parental bonding, specifically investigating the two fundamental dimensions of care and protection, and providing often conflicting results due to the studied population (clinical or nonclinical groups of different ages), and to the ED diagnostic subtype. For what concerns adult samples only, the majority of the findings points to a lower parental care perceived by patients with EDs, along with a sort of overprotection.12 In their systematic review, however, Tetley et al12 suggested that this characteristic might not be specific to patients with EDs, as they do not differ in the care and protection levels from patients with other psychiatric disorders. Moreover, the studies have to date failed in establishing a potential distinction among different ED diagnoses as regards the perceived parental bonding.

Only very few studies13,14 have specifically investigated parental bonding in adolescents with anorexia, although adolescence is very often the moment of the anorexic onset and at the same time the more fruitful life stage to treat it.15,16 It is worth noticing that, due to the specificity of the adolescent period, the results obtained in the adult sample are not always replicated unchanged in the adolescent samples. In fact, somehow surprisingly, both studies available13,14 found the adolescents with restricting-type anorexia to perceive an optimal parental bonding with both mothers and fathers. Unlike the binge-eating/purging-type patients,14 the former even perceive a better care and a lower control on the parents’ part, compared to the adolescents of the general population included in the control groups. For what concerns the first study by Russell et al,13 the explanation of the striking result may lay in the different treatment (and in the different treatment stage) already received by most of the patients included in the study. Not only the daughters in treatment but also the parents, receiving parental counseling, are plausibly making an effort to change their previous attitudes within the family relations, striving to give a positive image. Another possible explanation concerns the tendency to idealization and defensive avoidance, usually exhibited by the patients with restrictive conducts, which may use dismissing attachment strategies in order to control the negative feelings.3,8,14

Furthermore, there has been little research specifically into the parents’ own attachment patterns and perceived bonding, and whether there might be intergenerational transmission of these patterns remains still unclear. Ward et al7 hypothesized an intergenerational transmission of attachment patterns from the mothers to the daughters with anorexia. Although patients with anorexia and their mothers commonly showed a dismissive attachment style, the authors did not find an association between mothers’ and daughters’ attachment.7 Nevertheless, the study suggested that mothers of women with anorexia displayed a high rate of unresolved losses, which implies a lower capacity in the reflective functioning and emotional regulation on the mothers’ part, which may be transmitted or learned from mother to daughter. This kind of maternal psychological functioning might therefore be considered as a risk factor for the daughters’ development of anorexia nervosa.3,7 In line with those results, specificities on the paternal as well as on the maternal parental bonding toward their own parents were found by the only study17 conducted exclusively on adult patients, which has at least in part addressed the intergenerational transmission of parental bonding styles, administering the parental bonding instrument (PBI) questionnaire to parents of patients with EDs. Literature is, however, completely lacking in data on the intergenerational transmission of parental bonding and attachment representations in families of adolescent patients with EDs, and in particular with anorexia nervosa, and hence, the present study was conducted.

In particular, the first aim of the study was to investigate the perceived parental bonding, as described by the PBI, in a group of adolescents newly diagnosed with restricting-type anorexia, comparing them to healthy controls.

The second and main aim of the study was to broaden the limited knowledge on parental bonding in adolescents with anorexia and in their parents and to evaluate whether the families of adolescents with anorexia exhibit specific patterns of parental bonding, in order to better understand if these specific patterns can be transmitted from generation to generation.

To achieve these goals, a latent class analysis (LCA) approach was adopted to identify specific pattern of parental bonding transmission (separately for the maternal and the paternal bonding) comparing the families of patients with anorexia with families belonging to the general population. The perceived parental bonding was evaluated for what concerns both the mother and the father of the patients. Moreover, parental perceptions of their family of origin were evaluated as well, in order to adopt a family-level approach.

Methods

Participants

A total of 168 adolescents and parents participated in the study. They belonged to the 26 families of patients with anorexia and the 30 families of the control group. The adolescents had been consecutively admitted as inpatients to the Child and Adolescent Neuropsychiatry Unit, National Neurological Institute IRCCS C Mondino, University of Pavia, Italy, and the recruitment lasted 5 months.

Selection for the anorexia group was based on the following inclusion criteria: new diagnosis of anorexia nervosa, restricting subtype in accordance with the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR);18 age between 12 and 18 years; and current body mass index (BMI) below the tenth percentile per age and sex. Exclusion criteria instead were another major diagnosis (autism, schizophrenia and learning disabilities) and insufficient understanding of the Italian language. Adolescents for the control group were selected according to the following inclusion criteria: normal weight and age between 12 and 18 years. Exclusion criteria for the families of the control group were presence of adolescent’s symptoms related to food (either restrictive or purging or binge-eating conducts) or other psychopathological symptoms, and insufficient understanding of the Italian language.

The mean age of the 26 adolescent patients with anorexia (23 females and 3 males) was 14.62 years (standard deviation=2.00; range 12–18 years), and their mean current BMI was 15.55 (standard deviation=1.34). The control group was made up of 30 healthy subjects (27 females and three males), and the mean age of the adolescents was 14.30 years (standard deviation=2.07; range 12–18 years).

Procedure

Child and adolescent psychiatrists and clinical psychologists, not directly involved in the research project, recruited the patients and their parents and obtained their informed consent. A child neuropsychiatrist with special interest and clinical experience in adolescent anorexia evaluated all patients and collected a comprehensive medical and family history. Patients were diagnosed according to the DSM-IV-TR criteria for restricting-type anorexia nervosa.18 The diagnosis of potential comorbid disorders was supported by the Kiddie-SADS semi-structured interview.19

The control group was composed of parents and offspring, randomly recruited among the adolescents attending two local secondary schools. The agreement of the educational authorities was obtained, and the parents of the participating adolescents were required to give their informed consent to the study. To exclude a history of ED and the presence of psychopathological and behavioral disorders, the adolescents of the control group and their parents separately underwent a detailed anamnestic interview, during which a trained child and adolescent psychiatrist also administered the Eating Disorder Inventory-220 to the adolescents.

To evaluate parental rearing styles, all the participating adolescents and their parents were administered the PBI questionnaire.11 In particular, the adolescents with anorexia and their parents were requested to answer the questionnaire during their first week of hospitalization. All data were collected and treated in strict compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All parents and patients signed an informed consent, reviewed by the Institutional Review Board of the C Mondino Institute of Neurology of Pavia, which approved the study.

Measures

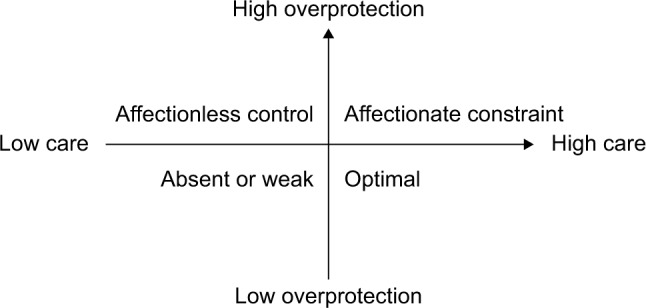

The PBI is a 25-item self-report measure of two fundamental dimensions of parental bonding, care and overprotection, concerning the mother and the father. Twelve care items reflect the dimension of affection and nurturing versus emotional rejection and neglect. Thirteen overprotection items assess the dimension of rigid control versus the fostering of autonomy. According to Parker et al’s instructions,11 the PBI items were rated on a Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very likely) to 4 (very unlikely). On the basis of the care and overprotection values emerging from the application of the questionnaire, four parenting styles have been defined: optimal bonding (high care and low overprotection), absent or weak bonding (low care and overprotection), affectionless control (high overprotection and low care) and affectionate constraint (high care and high overprotection) (Figure 1). α values ranged from 0.67 to 0.78 for parental care and parental protection scales. Good psychometric properties of the scale, with Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.74 to 0.95, have also been reported in literature.11

Figure 1.

Parental bonding styles emerged from the dimensions of care and over-protection.

Analyses

As a first approach to the data, in order to examine at a manifest level the PBI responses, before applying the LCA, the parental care and overprotection variables were analyzed by comparing the means of the two groups of families, using Student’s t-test.

Latent class analysis

The LCA approach21 was chosen to identify a latent categorical variable, namely to identify a hypothetical construct, accounting for the covariance between the observed variables. The LCA assumes the latent variable to be categorical and composed by a number of classes, which describe the presence or absence of the characteristics of the latent variable. Each class should represent a “profile” in relation to specific variables that are in this study: family roles, care and overprotection, typical of families of adolescents with anorexia and families of the control group. One latent variable with two classes representing the two family groups, families of adolescents with anorexia and families of the control group, was hypothesized in this context. The same hypothesis was formulated separately for maternal bonding and paternal one. The two latent class structures were supposed to be different in relation to the maternal and paternal bonding. However, given the explorative nature of the modeling approach used herein, no specific hypothesis about how the paternal bonding structure and the maternal bonding structure would differ was put forward. The variables (manifest variables) introduced in the LCA model were the group (anorexia and control), the family role (adolescent, mother and father), the PBI variable care (two levels: low care and high care) and the PBI variable overprotection (two levels: low overprotection and high overprotection).

The LCA approach has been extensively used in the psychological and medical literature to model the relations among variables in order to identify the underlying structure characterized by one or more latent categorical variables and draw a profile of people falling into one class or another.22,23 The model fitting the data were assessed by looking at the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). The chi square and the likelihood ratio statistics were also considered. The model is considered to have a good fit if both statistics have a probability higher than P=0.05. The LCA was performed with LEM software.24

Results

Description of the families of adolescents with anorexia and of the control families

With the aim of exploring the perceived parental bonding, measured by the PBI, in a group of adolescents newly diagnosed with restricting-type anorexia, and in their families, patients and parents were compared with adolescents and parents belonging to families from the general population. In Table 1, PBI care and overprotection scales scores are reported. The adolescents presented similar scores, whereas significant differences emerged between parents of adolescents with anorexia and parents of healthy controls (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean scores (M), standard deviations (SD) and t statistics and probability (P) values of PBI subscales for family roles and family groups (families of adolescents with anorexia and control families)

| Role | PBI subscale | Anorexia group

|

Control group

|

t-value (P) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Adolescent | Maternal care | 25.38 (4.290) | 26.43 (3.789) | -1.119 (ns) |

| Maternal overprotection | 13.19 (5.947) | 14.63 (6.092) | -1.003 (ns) | |

| Paternal care | 23.69 (4.663) | 24.13 (5.295) | -0.363 (ns) | |

| Paternal overprotection | 11.65 (5.284) | 11.43 (5.621) | 0.168 (ns) | |

| Mother | Maternal care | 22.42 (6.191) | 25.22 (4.757) | -2.248 (0.02) |

| Maternal overprotection | 16.08 (7.488) | 12.41 (6.120) | 2.351 (0.02) | |

| Paternal care | 21.38 (6.706) | 25.61 (3.715) | -3.67 (0.001) | |

| Paternal overprotection | 14.15 (7.546) | 12.12 (6.396) | 1.262 (ns) | |

| Father | Maternal care | 22.32 (5.031) | 24.40 (3.747) | -2.091 (0.03) |

| Maternal overprotection | 10.76 (5.876) | 14.14 (6.357) | -2.293 (0.02) | |

| Paternal care | 20.60 (5.339) | 22.68 (5.309) | -1.648 (ns) | |

| Paternal overprotection | 11.08 (5.923) | 10.82 (5.106) | 0.204 (ns) |

Abbreviations: PBI, parental bonding instrument; ns, nonsignificant.

LCA of maternal and paternal bonding

The LCA identified the two-latent-class models as hypothesized both for paternal and maternal bonding. The indices fitting the data were chi square =9.90, df=6, P=0.13, L2=9.99, df=6, P=0.13, AIC (L2) =-2.01 and BIC (L2) =-2.75 for paternal bonding, and chi square =11.73, df=6, P=0.06, L2=11.11, df=6, P=0.16, AIC (L2) =-1.11 and BIC (L2) =-17.63 for maternal bonding.

Once the latent structure was identified, the probability parameter estimates for each latent class revealed their distinctive characteristics (Table 2). For both paternal and maternal bonding, in general, Classes 1 and 2 presented rather similar probabilities, in the range 0.45–0.55, but each class evidenced different structures, which allowed the interpretation of the data. Substantial probability values used for the latent class interpretation are evidenced in bold in Table 2.

Table 2.

Two two-class latent class analyses (parental bonding and maternal bonding), manifest variables (group, family role, care and overprotection) and probability values

| Manifest variables | Latent variables

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal bonding

|

Paternal bonding

|

|||

| Class 1 (0.48) |

Class 2 (0.52) |

Class 1 (0.55) |

Class 2 (0.45) |

|

| Group | ||||

| Anorexia | 0.52 | 0.41 | 0.61 | 0.29 |

| Controls | 0.48 | 0.59 | 0.39 | 0.71 |

| Family role | ||||

| Adolescent | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.34 |

| Mother | 0.28 | 0.38 | 0.23 | 0.46 |

| Father | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 0.20 |

| Care | ||||

| Low | 0.75 | 0.46 | 0.81 | 0.21 |

| High | 0.25 | 0.54 | 0.19 | 0.79 |

| Overprotection | ||||

| Low | 0.36 | 0.71 | 0.59 | 0.58 |

| High | 0.64 | 0.29 | 0.41 | 0.42 |

Note: Substantial probability values for the interpretation are evidenced in bold.

Maternal bonding is characterized as follows: Class 1 is represented by the families of patients with anorexia (0.52), and the maternal bonding comes through the father’s transmission line (0.39) and is characterized by low care (0.75) and high overprotection (64). Class 2 is represented by the families of the control group (0.59), and in this case, the maternal bonding comes through the mother’s transmission line (0.38) and is characterized by high care (0.54) and low overprotection (0.71). Similarly, as far as paternal bonding is concerned, Class 1 is represented by the families of patients with anorexia (0.61). In particular, the paternal bonding comes through the father’s transmission line (0.44) and is characterized by low care (0.81) and low overprotection (0.59). Class 2 instead is represented by the control group (0.71), where the paternal bonding comes through her mother’s transmission line and is characterized by high care (0.79) and low overprotection (0.58).

Considering now the two groups, families of patients with anorexia versus control families, it is possible to evidence differences and analogies between them. For families of adolescents with anorexia (Class 1), both maternal (0.52) and paternal (0.61) bonding comes through the father’s transmission line (0.39 and 0.44, respectively, for maternal and paternal bonding). In fact, the adolescents’ father bonding is characterized by specificities concerning the relationship recalled both with his father and his mother. However, the kind of transmission is not the same; that is, maternal bonding is characterized by low care (0.75) and high overprotection (0.64), whereas paternal bonding is characterized by low care (0.81) and low overprotection (0.59).

For control families (Class 2), both maternal (0.59) and paternal (0.71) bonding comes through the mother’s transmission line (0.38 and 0.46, respectively, for maternal and paternal bonding). The parental bonding recalled by the control adolescents’ mother is characterized by specificities both in the maternal and in the paternal bonding. Maternal and paternal bonding are characterized in fact by high care (0.54 and 0.79, respectively) and low overprotection (0.71 and 0.58, respectively).

Discussion

In the comparison between the families of patients with anorexia and the families belonging to the general population, the LCA approach allowed to identify specific pattern of parental bonding transmission, separately for the maternal and the paternal bonding. The maternal bonding latent variable was characterized by two latent classes. The first latent class was represented by the group of families of patients with anorexia and characterized by a low level of maternal care along with a high level of overprotection, which corresponds to the affectionless control parenting style.11 As far as adolescents with anorexia are directly concerned, it is worth noticing that they did not contribute significantly in defining this first class. Surprisingly, it was essentially the father to recall and perceive the mother as careless and overcontrolling. However, the second profile (representing the second latent class), specified by a high level of maternal care and a low level of protection (corresponding to the optimal bonding),11 was characteristic of the control group (Table 2) and in particular of the control mothers.

The paternal bonding latent variable also presented two latent classes, which correspond respectively to the paternal bonding patterns of families of adolescents with anorexia and control families. A low level of paternal care characterized the first latent class, which specifies the families of patients with anorexia. Also in the case of paternal bonding, this profile did not receive a significant contribution from the adolescents with anorexia. Once again, however, the fathers of adolescents with anorexia perceived their own fathers as scarcely affectionate; that is, they perceived an absent or weak bonding.11 Conversely, the control families, and in particular the mothers, recalled their fathers as affectionate and warm toward them; that is, they recalled an optimal bonding style.11 Different from what has been shown for the maternal overprotection, the levels of paternal overprotection were not higher in families with adolescents with anorexia (Table 2).

The similarity of results between the patients with restricting-type anorexia and the control adolescents (Tables 1 and 2) in the perceived maternal as well as paternal bonding style confirms the few previous findings in adolescents13,14 and actually raises the question of a potentially altered report of parental bonding due to the lack of awareness or specific personality traits of this kind of patients. Patients with restrictive conducts are in fact well known for their implacable attempt to deny difficulties, which can lead them even to death.13 It could be just because of their major concerns regarding autonomy and separation that adolescents with anorexia did not judge their parents less than perfect in the PBI questionnaire:13,14 perhaps, they may feel that a critique could be too much aggressive and concretely threatening the parents. In line with the defensive attitudes typical of the dismissing attachment, which has been shown to characterize many patients with restricting-type anorexia,8 idealization and avoidance may thus prevent adolescents with anorexia from fighting with their parents, while many other adolescents, longing to win their autonomy, tend on the contrary to judge negatively parents and thus to overestimate the parental overprotection.13,25 The struggle for autonomy is indeed a key aspect characterizing the adolescent process of subjectivation and separation from the idealized parents of childhood, and at the same time, according to some theories, it is supposed to have a crucial role in EDs psychopathology, where this physiological adolescent process may encounter some complications.26,27

On the other hand, it is also possible to explain the absence of differences between adolescents with anorexia and controls, assuming that patients with restricting-type anorexia show a parental bonding genuinely analogous to that of adolescents belonging to the general population. This explanation seems however unlikely, based on the different findings obtained on patients with binge-eating/purging-type anorexia or with bulimia. Adolescent patients with binge-eating/purging-type anorexia in fact have been found to perceive their parental bonding as very inadequate with the mother as well as the father, described as excessively controlling and limiting the daughter’s autonomy and freedom.14 It is worth noticing that these findings are reported from the same study that found, in line with our results, adolescent with restricting-type anorexia to describe parents as very caring and permissive, feeling an optimal bonding with them.14 The authors hypothesized that the difference between the two groups of patients had to be explained by the opposed defense and attachment mechanisms adopted by the purging (more preoccupied) and restricting (more avoidant) patients. This conclusion may also be supported by the differences found in our sample between parents belonging to families of adolescents with anorexia and the parents belonging to the control group, where the bonding was perceived as more dysfunctional in the first group of parents.

Regarding the parents themselves, there has been little research specifically into the parents’ own perceived parental bonding, with the only exception of a study by Canetti et al17 conducted exclusively on adult patients, which found some specificities on the paternal and above all on the maternal side. Whether there might be intergenerational transmission of the attachment patterns along generations in patients with anorexia remains therefore still unclear. Overall, the results of the present study showed that the parents of adolescent patients with anorexia recall their own mothers as apprehensive and authoritarian (high overprotection) but not particularly affectionate and empathetic (low care) and their father as not particularly involved and affective in the children care (low care). In particular, the fathers’ relationships with their own parents were perceived as largely difficult, thus opening the hypothesis of a potential intergenerational transmission of the parental bonding in families of patients with anorexia, especially along the paternal line. The inter-generational transmission of a less affective and highly protection-oriented quality of parental bonding may provide a vulnerable environment for the complex ethiopathogenesis of EDs. These findings open, but do not close, the question regarding the relationship between parenting styles in different generations and the development and course of anorexia nervosa in the offspring.17

According to the still very scarce and limited existing research on attachment states of mind in parents of patients with EDs, mothers of patients with EDs in fact showed an increased degree of unresolved state of mind concerning, in particular, losses and traumas, which have not yet been completely elaborated.17,28 An issue of unresolved loss appears to be consistent with the early separation difficulties that may be considered among the risk factors for the EDs onset.28 According to the attachment theory, the representations and the internal working models of relationships can be transmitted through generations: the parents’ internal representation of relations with their own attachment figures may impact on their attitude toward their offspring, providing a sort of continuity across different generations’ parental behaviors. In line with these premises, in the only study specifically concerning the mothers of adult patients with anorexia, Ward et al7 found a high rate of insecure attachment representation and unresolved losses, which are often connected to deficits and difficulties in the emotional regulation and reflective functioning.2,4 Along with the attachment-related parenting behaviors, these latter characteristics may also in turn act as a risk factor in the mother–daughter relationship, potentially fostering the onset of an eating pathology in the daughters.3,7,28 Maternal negative perception of their own mothers (ie, PBI low levels of care) seemed in fact to be linked with the severity of eating symptoms in the daughters with anorexia.17

Consistent with these first findings on adults, the results of this study, conducted specifically on adolescents, may suggest that the intergenerational transmission of a less affective and highly protection-oriented quality of maternal bonding may provide a vulnerability to EDs, whose multifactorial symptomatic manifestation is clearly precipitated further by different conditions and later circumstances.29 However, since it is impossible to draw causal inferences in this type of cross-sectional study, alternatively it is also plausible that the patients’ parents change their perception of their parents after the onset of the child’s illness. The deep sense of crisis and guilt linked to the child’s condition may in fact lead parents to blame themselves and to perceive their own parental figures as inadequate as they feel to be at the moment for their ill offspring.

Although previous studies have mainly explored the maternal side, our results showed an important contribution of the paternal perceptions in defining a specific profile of families with an adolescent offspring with anorexia, as if the male line would have a preeminent role in the perceptions of family dysfunctions. A low level of care and affection perceived on the father’s part in fact characterized the families of patients with anorexia. This may imply that an intergenerational transmission of the parental bonding representations exists from father as well as from mother to offspring,17 suggesting that fathers’ perception of their own paternal figures’ involvement can play a pivotal role in their self-image as parents, and consequently influence the actual fathers’ behaviors with their offspring. Future studies will help to clarify this hypothesis, assessing not only the fathers’ perceptions of their own relationships with their parents but also the processes that link fathers’ evaluations of the parents’ attitudes with their own parenting representations and behaviors.

In addition to the more studied mother–daughter relationship, recent studies have pointed to the equally important role of the father–daughter bond as a risk or as protective factor in the onset and persistence of food-related symptoms.30–32 If on the one hand the therapeutic alliance with parents has been demonstrated to predict a positive outcome of family therapies for adolescents with anorexia,32,33 on the other hand the father’s exclusion may prevent treatment from success. The results from this controlled study also support the major paternal contribution in the family dynamics of patients with anorexia,10,34,35 and therefore are likely to indicate that therapeutic approaches should include the paternal participation in the treatment and at the same time address issues related to the fathers’ perceptions of the parental role in the relationship with the adolescent with anorexia.

Having said that, the limited number of patients and parents participating in the study, due to the particular clinical context of the research, imposes some limitations in interpreting the results of the LCA applied. Moreover, the use of self-reported measures only, along with the cross-sectional design of the study, is a limitation that suggests caution in interpreting the results, without drawing any causal conclusions. The self-reported retrospective measure of parental bonding has its undeniable advantages, such as the quickness to administer, and the information obtained directly from the individual concerned. Nevertheless, self-reported tools also have many weaknesses: the recall of the parental bonding is likely to be influenced by the subjective interpretation and modified by the real experiences of current relationships, particularly in the difficult and stressful situation of an anorexic onset.12 These measures are affected by the social desirability, which is particularly challenging in the case of patients with anorexia, which are well known for being inclined to provide idealized images, depleted from any negativity.13 Moreover, it is worth saying that the results obtained concern specifically the particular western cultural context, in which the research has been conducted, since parenting styles differ greatly between cultures.36–38 The PBI overprotection factor in fact showed some cross-cultural inconsistencies, since the more collective eastern cultures, and in particular the Japanese and Chinese ones, do not assign a positive value to child independence and autonomy.38 It is therefore likely that the positive link between high care and encouragement of freedom (low overprotection) may be specific only to western cultures, consequently representing a protective factor exclusively in these cultural contexts.

Conclusion

Further research, conducted using a multi-informant assessment, based on the self-report tools along with clinician-report interviews, will help clarify the intergenerational transmission of the families’ attachment and bonding patterns and its relative role in the origin and course of anorexia nervosa. This may help clinicians to provide more effective therapeutic treatments, tailored to the patient’s and parents’ needs. As opposed to making accusations for the offspring’s difficulties,8,29 involving parents in the treatment of adolescent patients with anorexia and addressing how their own attachment39 and parental bonding affect current relationships could be helpful for the whole family dynamics and thus for the patient’s outcome.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank all of the adolescents and parents who took part in the study, along with all those who have supported them with their precious help. LB warmly thanks her professor and PhD supervisor SM and her father UB for his passion for the difficult and rewarding work with children and adolescents, which he transmitted to her.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss: Volume 1. Attachment. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keating L, Tasca GA, Hill R. Structural relationships among attachment insecurity, alexithymia, and body esteem in women with eating disorders. Eat Behav. 2013;14(3):366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ringer F, Crittenden PM. Eating disorders and attachment: the effects of hidden family processes on eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2007;15(2):119–130. doi: 10.1002/erv.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tasca GA, Taylor D, Ritchie K, Balfour L. Attachment predicts treatment completion in an eating disorders partial hospital program among women with anorexia nervosa. J Pers Assess. 2004;83(3):201–212. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8303_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramacciotti A, Sorbello M, Pazzagli A, Vismara L, Mancone A, Pallanti S. Attachment processes in eating disorders. Eat Weight Disord. 2001;6(3):166–170. doi: 10.1007/BF03339766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Troisi A, Di Lorenzo G, Alcini S, Nanni RC, Di Pasquale C, Siracusano A. Body dissatisfaction in women with eating disorders: relationship to early separation anxiety and insecure attachment. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(3):449–453. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000204923.09390.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ward A, Ramsay R, Turnbull S, Steele M, Steele H, Treasure J. Attachment in anorexia nervosa: a transgenerational perspective. Br J Med Psychol. 2001;74(Pt 4):497–505. doi: 10.1348/000711201161145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zachrisson HD, Skårderud F. Feelings of insecurity: review of attachment and eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2010;18(2):97–106. doi: 10.1002/erv.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward A, Ramsay R, Treasure J. Attachment research in eating disorders. Br J Med Psychol. 2000;73(Pt 1):35–51. doi: 10.1348/000711200160282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duclos J, Dorard G, Berthoz S, et al. Expressed emotion in anorexia nervosa: what is inside the “black box”? Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(1):71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parker G, Tupling H, Brown LB. A parental bonding instrument. Br J Med Psychol. 1979;52(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tetley A, Moghaddam NG, Dawson DL, Rennoldson M. Parental bonding and eating disorders: a systematic review. Eat Behav. 2014;15(1):49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russell JD, Kopec-Schrader E, Rey JM, Beumont PJ. The Parental Bonding Instrument in adolescent patients with anorexia nervosa. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1992;86(3):236–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1992.tb03259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Pentima L, Magnani M, Tortolani D, Montecchi F, Ardovini C, Caputo G. Use of the Parental Bonding Instrument to compare interpretations of the parental bond by adolescent girls with restricting and binge/purging anorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord. 1998;3(1):25–31. doi: 10.1007/BF03339983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ackard DM, Richter S, Egan A, Cronemeyer C. Poor outcome and death among youth, young adults, and midlife adults with eating disorders: an investigation of risk factors by age at assessment. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47(7):825–835. doi: 10.1002/eat.22346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinhausen HC. Outcome of eating disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009;18(1):225–242. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canetti L, Kanyas K, Lerer B, Latzer Y, Bachar E. Anorexia nervosa and parental bonding: the contribution of parent-grandparent relationships to eating disorder psychopathology. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64(6):703–716. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent DA, Ryan ND, Rao U. K-SADS-PL. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(10):1208. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200010000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garner DM. Eating Disorder Inventory-2: Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hagenaars JA, McCutcheon A. Applied Latent Class Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mannarini S, Balottin L, Toldo I, Gatta M. Alexithymia and psychosocial problems among Italian preadolescents. A latent class analysis approach. Scand J Psychol. 2016;57(5):473–481. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mannarini S, Boffo M. Anxiety, bulimia, drug and alcohol addiction, depression, and schizophrenia: what do you think about their aetiology, dangerousness, social distance, and treatment? A latent class analysis approach. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(1):27–37. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0925-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vermunt JK. LEM A General Program for the Analysis of Categorical Data. Tilburg: Tilburg University, Department of Methodology and Statistic; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cubis J, Lewin T, Dawes F. Australian adolescents’ perceptions of their parents. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1989;23(1):35–47. doi: 10.3109/00048678909062590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brusset B. L’anorexie mentale des adolescentes [Adolescent anorexia nervosa] In: Lebovici S, Diatkine R, Soulè M, editors. Nouveau Traitè de psichiatrie de l’enfant et de l’adolescent [New Treaty of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry] 2nd ed. Paris: Quadrige/Presses Universitaires de France; 2004. French. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeammet P. Anoressia-Bulimia: il paradosso dell’adolescenza. [Anorexia-Bulimia: the paradox of adolescence] In: Nicolò AM, Russo L, editors. Una o più anoressie [One or more anorexia] Rome: Borla; 2010. Italian. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pace CS, Cavanna D, Guiducci V, Bizzi F. When parenting fails: alexithymia and attachment states of mind in mothers of female patients with eating disorders. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1145. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lock J, La Via MC, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Committee on Quality Issues (CQI) Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with eating disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(5):412–425. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones CJ, Leung N, Harris G. Father-daughter relationship and eating psychopathology: the mediating role of core beliefs. Br J Clin Psychol. 2006;45(Pt 3):319–330. doi: 10.1348/014466505x53489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horesh N, Sommerfeld E, Wolf M, Zubery E, Zalsman G. Father-daughter relationship and the severity of eating disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(1):114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Couturier J, Kimber M, Szatmari P. Efficacy of family-based treatment for adolescents with eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46(1):3–11. doi: 10.1002/eat.22042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Isserlin L, Couturier J. Therapeutic alliance and family-based treatment for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Psychotherapy (Chic) 2012;49(1):46–51. doi: 10.1037/a0023905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balottin L, Nacinovich R, Bomba M, Mannarini S. Alexithymia in parents and adolescent anorexic daughters: comparing the responses to TSIA and TAS-20 scales. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:1941–1951. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S67642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balottin L, Mannarini S, Mensi MM, Chiappedi M, Gatta M. Triadic interactions in families of adolescents with anorexia nervosa and families of adolescents with internalizing disorders. Front Psychol. 2017;7:2046. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.02046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Behzadi B, Parker G. A Persian version of the parental bonding instrument: factor structure and psychometric properties. Psychiatry Res. 2015;225(3):580–587. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Narita T, Sato T, Hirano S, Gota M, Sakado K, Uehara T. Parental child-rearing behavior as measured by the Parental Bonding Instrument in a Japanese population: factor structure and relationship to a lifetime history of depression. J Affect Disord. 2000;57(1–3):229–234. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu J, Li L, Fang F. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Parental Bonding Instrument. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(5):582–589. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mannarini S, Boffo M. The relevance of security: a latent domain of attachment relationships. Scand J Psychol. 2014;55(1):53–59. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]