Abstract

Objective

To examine impaired control over drinking behavior as a mediator of unique pathways from impulsive traits to alcohol outcomes in young adults and to investigate the moderating influence of self-reported sensitivity to alcohol on these pathways.

Method

Young adult heavy drinkers (N=172; n=82 women) recruited from the community completed self-report measures of impulsive traits (positive urgency, negative urgency, sensation seeking), alcohol sensitivity (Self-Rating of the Effects of Alcohol scale), impaired control over drinking, and alcohol use and problems. Multiple-groups path analysis was used to analyze the data.

Results

Path coefficients between urgency and impaired control were larger for individuals with lower versus higher self-reported sensitivity to alcohol. The same was true for the association between impaired control and alcohol problems. For participants lower on alcohol sensitivity, significant indirect paths were observed from both positive and negative urgency to all alcohol outcomes (quantity, frequency, and problems) mediated via impaired control. For participants higher on alcohol sensitivity, only the paths from negative urgency (but not positive urgency) to the three alcohol outcomes via impaired control were statistically significant. Sensation seeking was not uniquely associated with impaired control.

Conclusions

The findings indicate that relatively low sensitivity to the pharmacological effects of alcohol may exacerbate the association of urgency – especially positive urgency – with impaired control, supporting the notion that personality and level of response to alcohol may interact to increase risk for impaired control over drinking.

Introduction

Impaired control over drinking is a common experience among young adult drinkers and is predictive of heavy alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems (Chung and Martin, 2002; Leeman et al., 2012; Leeman et al., 2009; McCusker, 2006; Nagoshi, 1999). The impaired control construct encompasses both the failure to follow through on intentions to abstain from alcohol as well as failed attempts to limit the amount of alcohol consumed during a drinking episode (Heather et al., 1993; Kahler and Epstein, 1995). Impaired control is a hallmark of addictive disorders; it is one of the earliest symptoms to develop in alcohol dependent individuals and may be a precursor to more severe alcohol problems (Langenbucher and Chung, 1995; Leeman et al., 2009; Nelson et al., 1998). Identifying factors that contribute to impaired control could inform interventions to reduce heavy drinking among young adults.

Personality traits related to impulsivity may be particularly relevant to impaired control processes (Leeman et al., 2012). Indeed, impulsive traits are among the most important personality traits in the prediction of alcohol use and problems (Littlefield et al., 2014; Sher and Trull, 1994). Most researchers agree that impulsivity is a broad construct that encompasses several components. Whiteside and Lynam (2001) developed a comprehensive model of impulsivity that includes four related but distinct facets: urgency (the tendency to act rashly in response to intense emotions), sensation seeking (the tendency to seek out new and exciting experiences), lack of premeditation (the tendency to act without forethought), and lack of perseverance (difficulty maintaining focus on tasks; see also Whiteside et al., 2005). Urgency has been further subdivided into positive urgency and negative urgency, reflecting the tendency to act rashly when experiencing positive and negative emotions, respectively (Cyders and Smith, 2007; Cyders et al., 2007). These facets of impulsivity have been shown to relate differentially to alcohol use and problems. When examined together, urgency and sensation seeking appear to be more consistently related to alcohol use indices than perseverance and premeditation (see Cyders and Smith, 2008). Moreover, positive and negative urgency predict unique variance in alcohol-related problems, whereas sensation seeking is associated with alcohol use but tends not to predict alcohol problems (Cyders and Smith, 2008; Smith et al., 2007). Thus, facets of impulsivity appear to have distinct pathways to alcohol outcomes and therefore should be studied as separate and specific constructs (Coskunpinar et al., 2013; Littlefield et al., 2014).

A few studies have found associations between self-reported impulsivity and impaired control over drinking (see review by Leeman et al., 2012). Given that impulsive traits tend to emerge in childhood and predate drinking onset, it follows that impaired control may be one mechanism that explains the association between impulsivity and problem drinking. This is supported by studies that have found evidence for impaired control as a partial mediator of the association between traits related to impulsivity and alcohol problems (Patock-Peckham and Morgan-Lopez, 2006, 2009). However, most studies of the link between impulsivity and impaired control have tended to model impulsivity as a unitary construct (Leeman et al., 2012). More research is needed to determine whether impaired control may account for the influence of distinct facets of impulsivity on drinking behavior.

For example, high urgency may confer particular risk for impaired control relative to other facets of impulsivity such as sensation seeking. Individuals high on positive or negative urgency may make rash decisions to drink when experiencing intense emotions, leading to the breakdown of intentions to abstain and increased frequency of drinking, and they also may drink in a risky or haphazard manner in response to changes in emotions that accompany a drinking episode, leading to the failure to limit the quantity of alcohol consumed and increased alcohol related problems. In contrast, while young adults high on sensation seeking may be more likely to seek out parties and engage in drinking for the thrill of it, sensation seeking alone does not appear to elevate risk for hazardous drinking (Coskunpinar et al., 2013; Cyders et al., 2009). Thus, sensation seeking may not relate as strongly to impaired control after accounting for urgency. Although some studies have looked at distinct mediated pathways from impulsivity facets to drinking outcomes (Adams et al., 2012; Magid et al., 2007; Settles et al., 2010), impaired control over drinking has rarely been examined as a mediator of personality influences.

Furthermore, the associations between impulsive traits, impaired control, and alcohol outcomes may be influenced by individual differences in sensitivity to alcohol. A substantial literature indicates that individual differences in acute responses to alcohol relate to liability for heavy drinking and alcohol use disorder (for reviews, see Morean and Corbin, 2010; Quinn and Fromme, 2011; Ray et al., 2010). It is thought that individual differences in sensitivity to alcohol’s effects are partially a function of genetically-influenced biological processes (Schuckit, 2000), but may also be influenced factors such as acquired tolerance that results from repeated exposure to alcohol (Morean and Corbin, 2008). A common measure of alcohol sensitivity in survey-based studies is the Self-Rating of the Effects of Alcohol (SRE) questionnaire (Schuckit et al., 1997), which primarily assesses sensitivity to the sedative effects of alcohol. Higher SRE scores (which imply a larger number of drinks required in order to notice alcohol effects, and therefore lower sensitivity to alcohol) have consistently been shown to predict heavy drinking (Schuckit et al., 2007; Schuckit et al., 2009).

Additionally, it has been proposed that indices of alcohol sensitivity (or biological correlates thereof) might interact with trait or environmental risk factors to influence alcohol consumption (Erblich and Earleywine, 2003; Miranda et al., 2013; Schuckit, 1998). One possibility is that individual differences in acute alcohol responses set boundary conditions that determine the relative influence of other risk factors such as impulsivity. For example, Erblich and Earleywine (2003) found that self-reported stimulant effects during alcohol challenge moderated the relationship between behavioral undercontrol (a trait related to impulsivity) and alcohol use. Also, prospective research supports an interaction of behavioral undercontrol and alcohol sensitivity in predicting risk for alcohol use disorders (Schuckit, 1998). However, no studies to our knowledge have examined the interaction of impulsivity and alcohol sensitivity in impaired control processes, which may meditate the interactive effects of impulsivity and alcohol sensitivity on alcohol outcomes. For example, individuals high on positive or negative urgency may drink impulsively in response to emotions, and those who are also low on alcohol sensitivity may be less likely to notice early warning signs of intoxication, increasing their risk for impaired control over drinking. In turn, once impaired control occurs, individuals low on alcohol sensitivity may be likely to drink greater amounts overall, strengthening the relationship between impaired control and both quantity of alcohol consumption and alcohol problems.

The Present Study

The goal of this study was to examine specific indirect pathways from impulsivity facets to alcohol outcomes (quantity, frequency, and problems) mediated via impaired control over drinking. We also examined differences in these pathways as a function of self-reported alcohol sensitivity. We focused on positive urgency, negative urgency, and sensation seeking in our model given that these facets have been consistently shown to predict unique variance in alcohol use and problems (Cyders and Smith, 2008). We hypothesized that positive and negative urgency (but not sensation seeking) would indirectly predict alcohol outcomes via impaired control. Also, we predicted that these indirect associations would be stronger for individuals who require a relatively greater number of drinks to achieve alcohol effects (i.e., lower sensitivity to alcohol). Specifically, we hypothesized that alcohol sensitivity would moderate the paths from urgency to impaired control and from impaired control to typical quantity of alcohol consumed and greater alcohol problems. However, we hypothesized no moderating effect of alcohol sensitivity on the path from impaired control to drinking frequency.

Method

Participants

All study procedures were approved by our institution’s Research Ethics Board. Participants were heavy drinking young adults (N=172; n=82 women) who completed a baseline assessment as part of an experimental study of alcohol sensitivity. Participants selected one or more of the following categories to describe their ethnic/racial background: Caucasian (n=104; 61%), Asian (n=20; 12%), East Indian (n=16; 9%), Hispanic/Latino (n=16; 9%), Black/African American (n=15; 9%), Native North American (n=6; 4%), and other (n=21; 12%). Mean age was 19.82 years (SD=1.14), and 74% (n=127) were full-time students. Participants reported a mean of 19.76 (SD=12.39) drinking days in the past 90 days, with an average of 5.43 (SD=2.42) drinks per drinking day and 13.04 (SD=12.62) heavy drinking episodes (defined as 4+ drinks for women/5+ drinks for men).

Recruitment and Procedure

Recruitment consisted primarily of Internet advertisements on public and University websites targeting social drinkers in the Greater Toronto Area. Eligibility criteria included ages 18–25 years, at least one heavy drinking episode in the past month (4+/5+ drinks in one occasion for women/men), no past alcohol treatment or current desire/attempts to reduce drinking, no current psychiatric medications or diagnoses requiring treatment, no recent illicit drug use except cannabis, no contraindications for alcohol use, and no severe nicotine dependence. These criteria were evaluated in a telephone screen; eligible participants completed an in-person assessment at a laboratory in a hospital setting, from which the current data are derived. The assessment involved both self-report measures administered via computer, and a Time Line Follow Back assessment conducted by a trained interviewer.

Measures

UPPS-P Impulsivity Scales (Lynam et al., 2007)

The UPPS-P (Urgency, Premeditation, Perseverance, Sensation Seeking – with Positive Urgency) measures several facets of impulsivity. Participants used a 4-point scale (1=disagree strongly to 4=agree strongly) to rate the degree to which each item was descriptive of them. The UPPS-P provides a reliable and valid measure of these impulsivity facets (Cyders et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2007). As noted, in this study we were particularly interested in positive urgency (14 items; e.g., “When I am in a great mood, I tend to get into situations that could cause me problems), negative urgency (12 items; “When I feel bad, I will often do things I later regret in order to make myself feel better now”), and sensation seeking (12 items; “I generally seek new and exciting experiences and sensations”). Good internal consistency was observed in this sample, with Cronbach’s alphas of .93, .87, and .81 for positive urgency, negative urgency, and sensation seeking, respectively.

Impaired Control Scale (ICS; Heather et al., 1993)

Beliefs regarding the ability to exercise control over drinking behavior were assessed using the 10 items comprising Part 3 of the ICS (e.g., “Even if I intended having only one or two drinks, I would end up having more”). This subscale is useful for assessing impaired control in a sample of nondependent participants, who may be less likely to endorse a history of attempts to restrict drinking (see Heather et al., 1993). Items are rated on a 5 point scale ranging from 1=strongly disagree to 5= strongly agree. The ICS has good psychometric properties (Heather, Booth, & Luce, 1998), and Cronbach’s α in this sample was .75.

Timeline Followback (TLFB; Sobell and Sobell, 1992)

Primary drinking outcomes were derived from the TLFB, a structured calendar assessment of recent substance use. Past 90 day drinking frequency was calculated as the total number of days on which any alcohol use was reported. Typical quantity of alcohol consumed was represented by the average number of drinks reported per drinking day.

Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (RAPI; White and Labouvie, 1989)

Alcohol-related problems were assessed using the RAPI, one of the most commonly used measures of drinking problems for adolescents and young adults. Participants rated the frequency with which they experienced 23 indicators of alcohol-related problems (e.g., tolerance/withdrawal symptoms, academic problems, social/interpersonal consequences) on a scale from 0=Never to 4=More than 10 times. Cronbach’s α in this sample was .90.

Self-Rating of the Effects of Alcohol (SRE; Schuckit et al., 1997)

The SRE assesses the number of drinks needed to notice selected effects of alcohol intoxication (4 items: feeling different, dizziness/slurred speech, stumbling/loss of coordination, involuntary sleeping/passing out) for three different drinking periods (first 5 drinking occasions, most recent 3-month period of regular drinking, period of heaviest drinking). The SRE total score, calculated as the total number of drinks reported across all items (across all time periods) divided by the number of items endorsed, was used for the current analyses. A higher total score indicates more drinks needed to achieve these effects and therefore lower sensitivity to alcohol. Cronbach’s α was .91.

Data Analysis Plan

All variables in the model reasonably approximated univariate normal distributions (skewness ≤ 1.19 and kurtosis ≤ 1.97). A single extreme outlier was observed for both the alcohol problems and alcohol frequency variables; these outliers were recoded to one unit greater than the next most extreme value to reduce their influence (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007). Although 8 participants did not complete the TLFB, their data were retained in the analyses through the use of full information maximum likelihood estimation.

Our primary aim was to examine the indirect associations between the impulsivity traits and alcohol outcomes mediated through impaired control, and to test for differences in these pathways as a function of sensitivity to alcohol. To do so, we constructed a path model in Mplus version 7 (Muthén and Muthén, 2012). In this model, alcohol problems, drinking frequency, and average alcohol quantity were regressed on impaired control, and impaired control in turn was regressed on positive urgency, negative urgency, and sensation seeking. Each alcohol variable also was regressed directly on each impulsivity variable to control for the direct associations. Covariances were freely estimated among the impulsivity variables, and residual covariances were freely estimated among the alcohol variables. Model fit was considered good if the root-mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < .06, and both the comparative fit index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) > .95 (Hu and Bentler, 1999).

Because our goal was to examine whether the pathways from impulsivity traits to alcohol outcomes via impaired control differed based on sensitivity to alcohol, we estimated as a multiple groups model with higher vs. lower alcohol sensitivity as the grouping variable. We categorized participants into high or low alcohol sensitivity groups by performing a median-split on SRE scores separately within each sex. Consistent with previous studies, this approach allowed us to account for sex differences in alcohol sensitivity (Bartholow et al., 2010; Shin et al., 2010). While dichotomizing continuous variables is associated with limitations such as reduced statistical power, this approach to examining the moderating effects of alcohol sensitivity was preferred to including interactions between the continuous measure of alcohol sensitivity and impulsivity variables as these interaction terms were highly intercorrelated (r=.76), raising concerns about multicollinearity in the model.

The model was first estimated with all path coefficients, covariances, and residual covariances constrained to be equal across the high and low alcohol sensitivity groups. We hypothesized that alcohol sensitivity would have differential impacts on paths in the model (i.e., moderating the paths from urgency to impaired control but not sensation seeking to impaired control and moderating the paths from impaired control to alcohol quantity and alcohol problems but not to drinking frequency). Thus, we tested these specific a priori hypotheses by examining equality constraints across high and low alcohol sensitivity groups for each of these paths separately rather than conducting an omnibus test of model invariance. Specifically, nested model tests were conducted to examine whether the model fit was improved by relaxing the equality constraints on these paths one at a time. If relaxing the equality constraint on any given path coefficient results in a significant change in the model chi-square (p<.05), this indicates that the path is not equal across groups. A modified model was specified in which paths that were found to differ across groups were allowed to vary freely and the equality constraints were retained on the other paths. The fit of this final model was then evaluated.

Next, we examined mediation by estimating specific indirect paths from impulsivity traits to alcohol outcomes via impaired control. These indirect associations were estimated separately for the high and low alcohol sensitivity groups. Bootstrapping was used to calculate bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals for the indirect associations.

Results

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations among all variables. The multiple-groups path model with all parameters constrained to be equal across the high and low alcohol sensitivity groups did not fit the data well, χ2(21)=29.08, p=.11, RMSEA=.07, TLI=.97, CFI=.94. Results of the nested model tests showed that model fit was improved by releasing the equality constraints on the paths from positive urgency to impaired control (Δχ2=6.45, p=.01), negative urgency to impaired control (Δχ2=3.71, p=.05), and impaired control to alcohol problems (Δχ2=6.28, p=.01). These results suggest that these paths are not equal across high and low alcohol sensitivity groups, albeit the chi-square difference test for the path from negative urgency to impaired control was bordering statistical significance. Accordingly, the model was modified to allow these three paths to freely vary across groups. Releasing the equality constraints on the paths from sensation seeking to impaired control, impaired control to drinking frequency, and impaired control to drinking quantity did not improve model fit (p>.05), and so the equality constraints were retained on these paths. This modified model fit the data very well, χ2(18)=16.28, p=.57, RMSEA<.001, TLI=1.02, CFI=1.00.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations among variables in the model and sex.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Positive Urgency | 1 | 1.95 | 0.61 | ||||||||

| 2. Negative Urgency | .69** | 1 | 2.36 | 0.58 | |||||||

| 3. Sensation Seeking | .19* | −.01 | 1 | 3.07 | 0.53 | ||||||

| 4. Impaired Control | .56** | .55** | .05 | 1 | 2.05 | 0.77 | |||||

| 5. Alcohol Problems | .43** | .49** | .12 | .68** | 1 | 11.27 | 9.46 | ||||

| 6. Drinking Frequency | .20* | .17* | .12 | .37** | .36** | 1 | 19.76 | 12.39 | |||

| 7. Alcohol Quantity | .15 | .04 | .21** | .28** | .34** | .27** | 1 | 5.43 | 2.42 | ||

| 8. Alcohol sensitivity (SRE total score) | .22** | .12 | .15 | .32** | .37** | .26** | .58** | 1 | 5.69 | 2.16 | |

| 9. Sex (1=male; 2=female) | −.12 | .12 | −.33** | .06 | −.03 | −.06 | −.32** | −.31** | 1 | 1.48 | 0.50 |

Note. SRE = Self-Rating of the Effects of Alcohol;

p<.05;

p <.01.

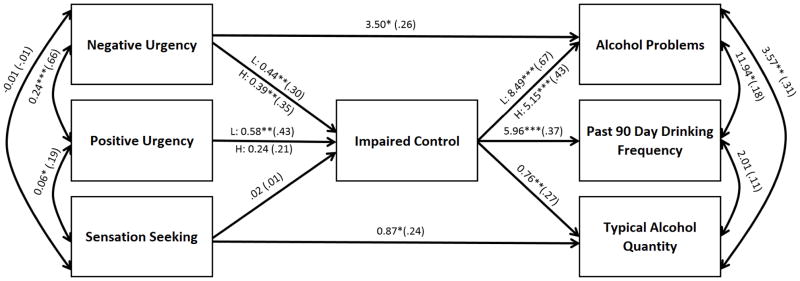

Figure 1 shows the final modified path model. In the model shown in Figure 1, only those paths that were found not to be equal in the nested model tests were estimated separately for the high and low alcohol sensitivity groups; all other coefficients were not significantly different across groups and were therefore constrained to be equal. Figure 1 shows that the coefficients for the paths from positive and negative urgency to impaired control were larger for participants who were relatively low on alcohol sensitivity than for participants who were relatively high on alcohol sensitivity. This difference was much more pronounced for positive urgency, whereas the difference in path coefficients for negative urgency was smaller in magnitude. For the low alcohol sensitivity group, both positive and negative urgency predicted unique variance in impaired control. However, in the high alcohol sensitivity group, only negative (but not positive) urgency was significantly associated with impaired control. Impaired control, in turn, was significantly associated with all three of the alcohol outcomes. Also, the path coefficient from impaired control to alcohol problems was not equal across alcohol sensitivity groups, and indeed was larger for participants lower on alcohol sensitivity. Sensation seeking was not associated with impaired control for either group. The only statistically significant direct paths from the impulsivity variables to the alcohol variables were from negative urgency to alcohol problems and from sensation seeking to typical alcohol quantity. All direct paths were retained in the final model regardless of level of significance, although only the significant direct paths are shown in Figure 1 for clarity.

Figure 1.

Multiple-groups path model of the associations between the impulsive traits, impaired control over drinking, and alcohol outcomes. Unstandardized estimates are shown with standardized estimates in parentheses. Participants were categorized as lower or higher on sensitivity to alcohol based on median splits within sex. All parameters are constrained to be equal across high and low alcohol sensitivity groups except the paths from positive urgency and negative urgency to impaired control, and from impaired control to alcohol problems. These paths were allowed to free vary across groups, and their respective estimates are shown. L = Low alcohol sensitivity group (higher SRE score). H = High alcohol sensitivity group (lower SRE score). All direct paths from each impulsivity trait to each alcohol outcome were included in the model, but only those direct paths that were statistically significant are shown for clarity. Errors also are omitted from the figure. *p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001.

Table 2 presents the estimates and confidence intervals for the indirect associations between the impulsivity traits and each alcohol outcome mediated via impaired control. For the low alcohol sensitivity group, all of the estimates of the indirect paths for positive and negative urgency were significantly different from zero (i.e., 95% CIs do not contain zero). For the high alcohol sensitivity group, the indirect associations between negative urgency and each alcohol outcome were significant (95% CIs do not contain zero), whereas the indirect paths from positive urgency to each alcohol outcome via impaired control were not (95% CIs contain zero). All of the confidence intervals for the indirect associations between sensation seeking and the alcohol outcomes mediated via impaired control contained zero for both alcohol sensitivity groups.

Table 2.

Estimates of indirect associations between personality and alcohol variables mediated via impaired control for participants lower and higher on sensitivity to alcohol.

| Outcome | Predictor | Lower Alcohol Sensitivity | Higher Alcohol Sensitivity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Estimate | 95% CI | β | Estimate | 95% CI | β | ||

| Alcohol Problems | Positive Urgency | 4.93* | [2.23, 8.48] | .29 | 1.21 | [−0.03, 3.45] | .09 |

| Negative Urgency | 3.72* | [1.33, 7.71] | .20 | 1.98* | [0.49, 4.35] | .15 | |

| Sensation Seeking | 0.13 | [−1.33, 1.73] | .01 | 0.08 | [−0.77, 1.19] | .01 | |

| Drinking Frequency | Positive Urgency | 3.46* | [1.60, 6.82] | .16 | 1.41 | [−0.01, 3.64] | .08 |

| Negative Urgency | 2.61* | [0.72, 5.31] | .11 | 2.30* | [0.68, 5.12] | .13 | |

| Sensation Seeking | 0.09a | [−0.98, 1.32] | .00 | 0.09a | [−0.98, 1.32] | .00 | |

| Alcohol Quantity | Positive Urgency | 0.44* | [0.13, 0.97] | .11 | 0.18 | [−0.01, 0.49] | .06 |

| Negative Urgency | 0.33* | [0.09, 0.74] | .08 | 0.29* | [0.07, 0.65] | .09 | |

| Sensation Seeking | .01b | [−0.14, 0.16] | .00 | 0.01b | [−0.14, 0.16] | .00 | |

Note. Participants were categorized as lower or higher on sensitivity to alcohol based on median splits within sex. All indirect associations are mediated via impaired control over drinking. Estimates sharing the same superscript letter are constrained to be equal across alcohol sensitivity groups. Bootstrapping was used to derive bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CI).

95% CI does not contain zero.

Discussion

The findings of this study further our understanding of the role of impaired control in the links between impulsive traits and alcohol use and problems. In our path model, we observed significant indirect associations from both positive and negative urgency to all three of the alcohol outcomes (quantity, frequency, problems) via impaired control. In addition, self-reported alcohol sensitivity moderated the strength of these associations, such that these paths were stronger for individuals with relatively lower sensitivity to alcohol’s effects. This study extends past research in this area by integrating both alcohol sensitivity and trait vulnerability into a model of impaired control over drinking and associated drinking outcomes.

As hypothesized, we found that both positive and negative urgency were more strongly associated with impaired control over drinking than sensation seeking. This is consistent with theoretical conceptualizations of these different facets of impulsivity. Because alcohol use often takes place in the context of emotional experiences (e.g., celebratory drinking, drinking to cope with negative emotions; Cooper et al., 1995), the tendency to act rashly and without restraint when experiencing positive and negative emotions (characteristic of individuals high on urgency) may increase the likelihood of impaired control over drinking. Impaired control, in turn, was significantly associated with more frequent, heavier, and more problematic drinking. This resulted in significant indirect pathways from urgency to multiple drinking outcomes via impaired control. However, it is important to note that a significant direct path between negative urgency and alcohol problems was observed, suggesting that impaired control did not fully explain the relationship between negative urgency and alcohol problems. This is consistent with studies that have found that drinking to regulate negative affect can lead to alcohol problems independent from alcohol consumption levels (Cooper et al., 1995; Merrill and Read, 2010).

In contrast, sensation seeking did not predict unique variance in impaired control. Sensation seeking reflects a drive to seek out new and exciting experiences, but not necessarily unplanned action or impairment associated with these experiences. Thus, while young adults who are high on sensation seeking may be attracted to parties and other drinking contexts for the fun and excitement, sensation seeking alone is not likely to lead them to experience impaired control over their drinking. That sensation seeking was directly associated with typical quantity of alcohol consumed but not alcohol problems is consistent with this conceptualization as well as previous research showing that sensation seeking is associated with alcohol use but not alcohol problems (Cyders and Smith, 2008; Stautz and Cooper, 2013).

Also consistent with hypotheses, we found that self-reported sensitivity to alcohol moderated the associations between the urgency traits and impaired control over drinking; these associations were stronger for individuals with lower versus higher alcohol sensitivity (based on sex-specific median splits in the current sample). This finding suggests that relatively lower alcohol sensitivity may exacerbate the association of urgency with impaired control. Perhaps those who are relatively low on sensitivity to alcohol are not as quick to perceive the warning signs that they have consumed too much alcohol, which may increase the likelihood that urgency-related rash drinking might lead to impaired control. Individuals higher on alcohol sensitivity, in contrast, may recognize these warning signs earlier, alerting them to exercise more caution when drinking.

Also as predicted, we found that alcohol sensitivity moderated the association between impaired control and alcohol problems such that impaired control was more strongly related to alcohol-related problems for individuals lower on alcohol sensitivity. This finding suggests that when individuals who are lower on alcohol sensitivity experience impaired control over drinking, it leads to more negative outcomes, potentially as a function of achieving higher BACs before noticing the intoxicating effects of alcohol. Thus, an important finding of this study is that lower sensitivity to alcohol exacerbates the indirect association between urgency and alcohol problems by strengthening both links in the chain: the influence of urgency on impaired control, and the influence of impaired control on alcohol problems. However, we did not observe the expected moderating impact of alcohol sensitivity on the path from impaired control to quantity of alcohol consumption, suggesting that alcohol sensitivity and impaired control interact to increase alcohol problems but not alcohol use per se. These findings provide new insight into the nature of the relationships between urgency, impaired control, and alcohol outcomes.

Furthermore, we found that alcohol sensitivity had a larger impact on the path from positive urgency to impaired control than the path from negative urgency to impaired control (see Figure 1). Moreover, for individuals higher on alcohol sensitivity, the indirect associations between positive urgency and the three alcohol outcomes via impaired control were not statistically significant, but the indirect paths from negative urgency to the alcohol outcomes were statistically significant. This finding is consistent with research showing that negative-affect pathways to drinking tend to have a more robust link with drinking problems than positive-affect pathways (Cooper et al., 1995; Simons et al., 2005). Thus, it is perhaps not surprising that negative urgency’s influence on alcohol use and problems via impaired control does not appear to be as strongly mitigated by greater alcohol sensitivity. An additional consideration is that alcohol’s relative effects on positive and negative mood may lead to differences in the degree to which alcohol sensitivity impacts impaired control pathways to drinking outcomes for positive versus negative urgency. Future studies that directly assess mood will be important to further elucidate urgency-related impaired control processes.

There are some limitations to this study that highlight important directions for future research. First, we conducted median-splits on the SRE measure to form high and low alcohol sensitivity groups, which had the advantage of reducing multicollinearity in the model but also may have introduced some limitations including reduced statistical power. Moreover, although the temporal ordering of the variables is supported by theory, it cannot be directly established by this study due to the cross-sectional nature of the data. Future work should attempt to replicate this model with longitudinal data. Also, our assessments of alcohol sensitivity and impulsivity traits were based on self-report. Some of the items in the SRE asked participants to provide retrospective reports of fairly remote information, which does not allow for the clear distinction between pre-existing individual differences in alcohol sensitivity and alcohol sensitivity due to acquired tolerance. Indeed, other factors may also have influenced responses on the SRE, including alcohol expectancies and other cognitive factors that may have led to biased recall. Future studies could attempt to minimize this bias by studying these questions using experimental paradigms, with particular emphasis on indicators of alcohol sensitivity and impaired control that are not reliant on self-report (see Hendershot and Wardell, 2014; Weafer and Fillmore, 2008).

Another feature of the SRE is that if focuses primarily on sedative effects of alcohol, precluding the examination of the possible role of sensitivity to the stimulating effects of alcohol in impaired control processes. For example, perhaps heightened sensitivity to alcohol’s stimulating effects is more relevant for the influence of sensation-seeking on drinking behavior. A related issue is that we did not assess the degree to which participants perceived the effects of alcohol to be positive or negative, making it difficult to draw any conclusions with respect to the motivational significance of the alcohol effects measured by the SRE. Thus, future research should include a more comprehensive assessment of alcohol sensitivity to help disentangle the relevance of sensitivity to arousal vs. sedation and positive vs. negative effects of alcohol to impaired control.

In addition, while this study demonstrates that impaired control is an important mediator of the link between urgency and alcohol outcomes, other mechanisms also have been observed, including alcohol expectancies and drinking motives (Adams et al., 2012; Settles et al., 2010). Indeed, that we observed a significant direct path from negative urgency to alcohol problems suggests that impaired control was only a partial mediator of this association. An important next step will be to examine multiple mediators simultaneously. Finally, it is important to note that the range of alcohol sensitivity observed in this sample may have been restricted to some extent by our focus on heavy drinking young adults. Future work should attempt to replicate these findings with a wider range of drinkers, including light-drinking samples and clinical populations.

In summary, we found that impaired control over drinking mediated the associations between urgency and alcohol use and problems, and that sensitivity to alcohol moderated these associations. Also, these paths were specific to positive and negative urgency and were not observed for sensation seeking. The results provide further evidence that different facets of impulsivity confer differential risk for problematic drinking, and highlight the importance of considering biological vulnerability in conjunction with personality traits. These findings may inform interventions to reduce hazardous drinking among young adults, suggesting that impaired control over drinking may be an especially important treatment target among individuals with relatively high levels of urgency and low levels of alcohol sensitivity.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grants 260418, 288905, 307742), ABMRF/The Foundation for Alcohol Research, and the Ontario Mental Health Foundation to Christian S. Hendershot.

References

- Adams ZW, Kaiser AJ, Lynam DR, Charnigo RJ, Milich R. Drinking motives as mediators of the impulsivity-substance use relation: Pathways for negative urgency, lack of premeditation, and sensation seeking. Addictive behaviors. 2012;37:848–855. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholow BD, Lust SA, Tragesser SL. Specificity of P3 event-related potential reactivity to alcohol cues in individuals low in alcohol sensitivity. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:220–228. doi: 10.1037/a0017705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Martin CS. Concurrent and discriminant validity of DSM-IV symptoms of impaired control over alcohol consumption in adolescents. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26:485–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskunpinar A, Dir AL, Cyders MA. Multidimensionality in impulsivity and alcohol Use: A meta-analysis using the UPPS model of impulsivity. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37:1441–1450. doi: 10.1111/acer.12131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Flory K, Rainer S, Smith GT. The role of personality dispositions to risky behavior in predicting first-year college drinking. Addiction. 2009;104:193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Mood-based rash action and its components: Positive and negative urgency. Personality and individual differences. 2007;43:839–850. [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT, Spillane NS, Fischer S, Annus AM, Peterson C. Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: Development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19:107–118. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erblich J, Earleywine M. Behavioral undercontrol and subjective stimulant and sedative effects of alcohol intoxication: Independent predictors of drinking habits? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:44–50. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000047300.46347.CE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, Tebbutt JS, Mattick RP, Zamir R. Development of a scale for measuring impaired control over alcohol consumption: A preliminary report. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54:700–709. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot CS, Wardell JD. Alcohol sensitivity in the context of the acquired preparedness model. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;73:713–715. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Epstein EE. Loss of control and inability to abstain: The measurement of and the relationship between two constructs in male alcoholics. Addiction. 1995;90:1025–1036. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.90810252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenbucher JW, Chung T. Onset and staging of DSM-IV alcohol dependence using mean age and survival-hazard methods. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:346–354. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.2.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Patock-Peckham JA, Potenza MN. Impaired control over alcohol use: An under-addressed risk factor for problem drinking in young adults? Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2012;20:92–106. doi: 10.1037/a0026463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Toll BA, Taylor LA, Volpicelli JR. Alcohol-induced disinhibition expectancies and impaired control as prospective predictors of problem drinking in undergraduates. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:553–563. doi: 10.1037/a0017129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Stevens AK, Sher KJ. Impulsivity and alcohol involvement: Multiple, distinct constructs and processes. Current Addiction Reports. 2014;1:33–40. doi: 10.1007/s40429-013-0004-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam D, Smith G, Cyders M, Fischer S, Whiteside S. The UPPS-P: A multidimensional measure of risk for impulsive behavior. Unpublished technical report 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Magid V, MacLean MG, Colder CR. Differentiating between sensation seeking and impulsivity through their mediated relations with alcohol use and problems. Addictive behaviors. 2007;32:2046–2061. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCusker C. Towards understanding loss of control: An automatic network theory of addictive behaviours. In: Munafò M, Albery IP, editors. Cognition and addiction. New York, NY US: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 117–145. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Read JP. Motivational pathways to unique types of alcohol consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:705–711. doi: 10.1037/a0020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R, Reynolds E, Ray L, Justus A, Knopik VS, McGeary J, Meyerson LA. Preliminary evidence for a gene–environment interaction in predicting alcohol use disorders in adolescents. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37:325–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, Corbin WR. Subjective alcohol effects and drinking behavior: The relative influence of early response and acquired tolerance. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:1306–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, Corbin WR. Subjective response to alcohol: A critical review of the literature. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34(3):385–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2012. pp. 197–200. [Google Scholar]

- Nagoshi CT. Perceived control of drinking and other predictors of alcohol use and problems in a college student sample. Addiction Research. 1999;7:291–306. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CB, Heath AC, Kessler RC. Temporal progression of alcohol dependence symptoms in the U.S. household population: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of Consulting and Clinic Psychology. 1998;66:474–483. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, Morgan-Lopez AA. College drinking behaviors: Mediational links between parenting styles, impulse control, and alcohol-related outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:117–125. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, Morgan-Lopez AA. Mediational links among parenting styles, perceptions of parental confidence, self-esteem, and depression on alcohol-related problems in emerging adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:215–226. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PD, Fromme K. Subjective response to alcohol challenge: A quantitative review. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35:1759–1770. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray LA, Mackillop J, Monti PM. Subjective responses to alcohol consumption as endophenotypes: Advancing behavioral genetics in etiological and treatment models of alcoholism. Substance Use & Misuse. 2010;45:1742–1765. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2010.482427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA. Biological, psychological and environmental predictors of the alcoholism risk: A longitudinal study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1998;59:485–494. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA. Genetics of the risk for alcoholism. The American Journal on Addictions. 2000;9:103–112. doi: 10.1080/10550490050173172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Danko GP, Pierson J, Hesselbrock V, Bucholz KK, … Brandon R. The ability of the Self-Rating of the Effects of Alcohol (SRE) Scale to predict alcohol-related outcomes five years later. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:371–378. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Tipp JE. The Self-Rating of the Effects of Alcohol (SRE) form as a retrospective measure of the risk for alcoholism. Addiction. 1997;92:979–988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Trim R, Fukukura T, Allen R. The overlap in predicting alcohol outcome for two measures of the level of response to alcohol. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33:563–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00870.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles RF, Cyders M, Smith GT. Longitudinal validation of the acquired preparedness model of drinking risk. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:198–208. doi: 10.1037/a0017631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Trull TJ. Personality and disinhibitory psychopathology: Alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:92–102. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin E, Hopfinger JB, Lust SA, Henry EA, Bartholow BD. Electrophysiological evidence of alcohol-related attentional bias in social drinkers low in alcohol sensitivity. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:508–515. doi: 10.1037/a0019663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM, Correia CJ, Hansen CL, Christopher MS. An affective-motivational model of marijuana and alcohol problems among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:326–334. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Fischer S, Cyders MA, Annus AM, Spillane NS, McCarthy DM. On the validity and utility of discriminating among impulsivity-like traits. Assessment. 2007;14:155–170. doi: 10.1177/1073191106295527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biochemical methods. Totowa, NJ US: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Stautz K, Cooper A. Impulsivity-related personality traits and adolescent alcohol use: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33:574–592. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 5. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Weafer J, Fillmore MT. Individual differences in acute alcohol impairment of inhibitory control predict ad libitum alcohol consumption. Psychopharmacology. 2008;201:315–324. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1284-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:669–689. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR, Miller JD, Reynolds SK. Validation of the UPPS impulsive behaviour scale: A four-factor model of impulsivity. European Journal of Personality. 2005;19:559–574. [Google Scholar]