Abstract

cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB) is a nuclear transcription factor that has been implicated in the pathogenesis and maintenance of various types of human cancers. Identification of small molecule inhibitors of CREB-mediated gene transcription has been pursued as a novel strategy for developing cancer therapeutics. We recently discovered a potent and cell-permeable CREB inhibitor called 666-15. 666-15 is a bisnaphthamide and has been shown to possess efficacious anti-breast cancer activity without toxicity in vivo. In this study, we designed and synthesized a series of analogs of 666-15 to probe the importance of regiochemistry in naphthalene ring B. Biological evaluations of these analogs demonstrated that the substitution pattern of the alkoxy and carboxamide in naphthalene ring B is very critical for maintaining potent CREB inhibition activity, suggesting that the unique bioactive conformation accessible in 666-15 is critically important.

Keywords: CREB, cancer, 666-15, regioisomer, bioactive conformation

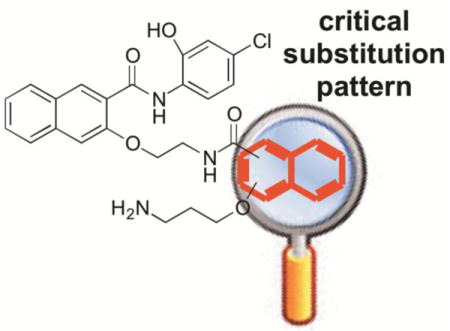

Graphical abstract

Cancer is a heterogeneous group of complex and multigenic disease. Numerous oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes have been identified to directly contribute to the development and maintenance of transformed cellular states.1 During the past three decades, various types of targeted therapies (e.g. kinase inhibitors and hormonal therapies) have been developed for various types of cancers.2 However, most of these therapies face a formidable challenge of rapidly developed drug-resistance through up-regulating alternative cellular survival pathways.3,4 Therefore, identifying and targeting novel regulators of cancer development and maintenance have been the subject of intense cancer biology and chemical biology studies including those from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project.5 Among these novel targets are transcription factors that are deregulated in various cancer cells.6

Cyclic-AMP response element (CRE) binding protein (CREB) is a stimulus-activated transcription factor.7 CREB normally resides in the nucleus in an inactive state.8 Upon phosphorylation at Ser133 by various kinases including protein kinase A (PKA), protein kinase B (PKB/Akt), p90 ribosomal S6 kinase (pp90RSK) and Ras-activated mitogen activated protein kinases, CREB’s transcription activity is initiated by recruiting CREB-binding protein (CBP) and its closely related paralog p300 and other proteins in the transcription machinery to the gene promoters.9,10 Similar to other phosphorylated proteins, CREB phosphorylation is dynamic and tightly regulated to ensure its transcription activity is tightly coupled to the environment cues. Three protein phosphatases have been identified to be able to dephosphorylate CREB to inactivate its transcription activity. These are protein phosphatase 1 (PP1),11 protein phosphatase 2A12 and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)13. Mechanistically, the kinases that can phosphorylate and activate CREB are proto-oncogenes that are often overactivated in tumor cells while those phosphatases that can dephosphorylate CREB are known as tumor suppressors that are often inactivated or deleted in tumor cells. As a consequence, CREB is often overactivated in cancer cells to drive tumor development and maintenance. Indeed, this overactivation has been observed in numerous cancer tissues.9,14–16

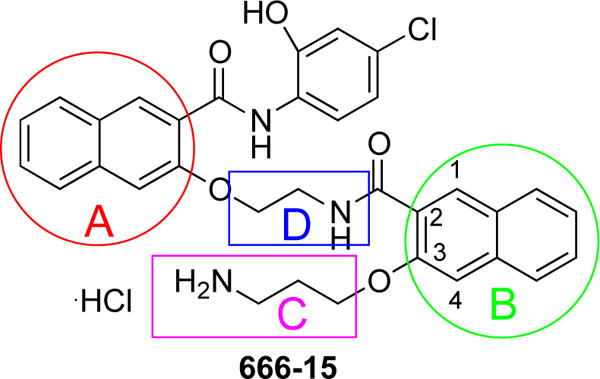

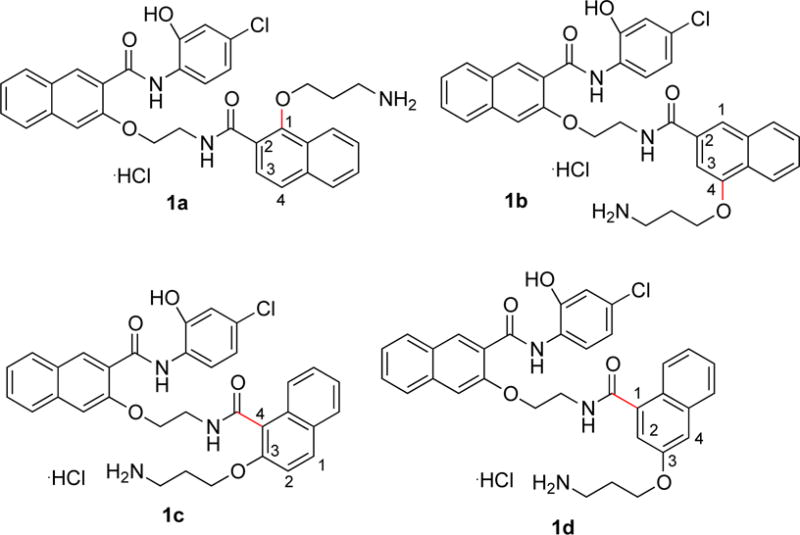

Because CREB sits at a signaling hub of multiple oncogenic signaling pathways and is overactivated in many cancer tissues, CREB has been recognized as an important oncology drug targets.9 We and others have been investigating small molecule inhibitors of CREB as potential cancer therapeutics.9,17–25 Among these, 666-15 (Figure 1) represents the most potent inhibitor of CREB-mediated gene transcription with efficacious in vitro and in vivo anti-breast cancer activity without harming normal cellular homeostasis.20,26 Preliminary structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies identified the following (Figure 1): 1) the naphthyl rings A and B are critical for activity; 2) minor alterations of the two carbon linkers C and D can dramatically affect the CREB inhibition activity; and 3) the primary amino group is essential for optimal CREB inhibition.20 In this communication, we describe our investigation on the SAR of region B with different regioisomers by varying one substitution at a time on naphthalene ring B. By keeping the carboxamide substitution at position 2, two isomers 1a and 1b (Figure 2) were designed by moving the alkoxy group to position 1 and 4, respectively. On the other hand, by maintaining the alkoxy group at position 3, isomers 1c and 1d (Figure 2) were designed through changing the carboxamide substitution to position 4 and 1, respectively.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of 666-15.

Figure 2.

Designed regioisomers 1a–1d by changing the substitution pattern on naphthalene ring B of 666-15.

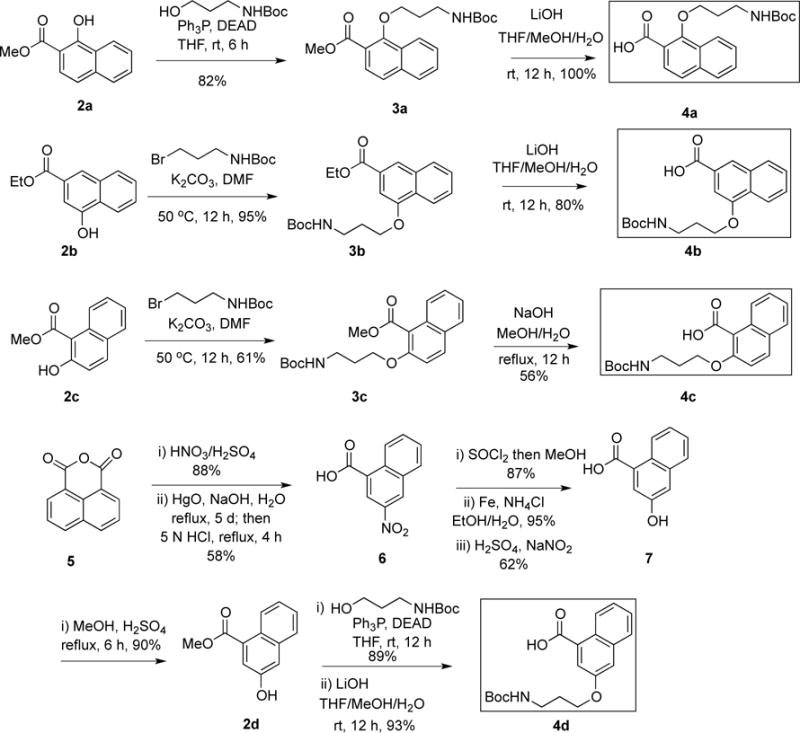

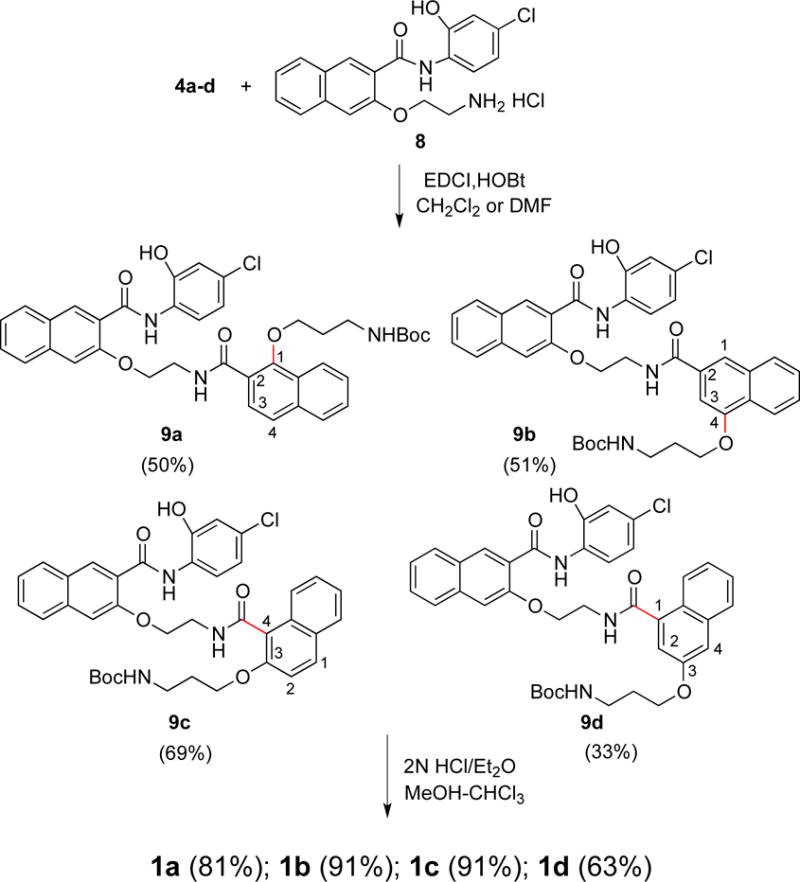

The general strategy to the synthesis of regioisomers 1a–1d is similar to our previously described synthesis of 666-15.20 The key is to synthesize building blocks 4a–4d (Scheme 1) and then couple them to the same amine 8 (Scheme 2). The carboxylic acids 4a–4d were synthesized according to Scheme 1. Compounds 2a–2c are either commercially available or could be conveniently synthesized from their corresponding acids by acid-catalyzed esterification reaction as described before.17 The Boc-protected aminopropyl side chain was either installed by Mitsunobu reaction (for 3a) with alcohol or O-alkylation reaction with bromide (for 3b and 3c) to give ethers 3a–3c, which were further saponified by LiOH or NaOH to generate required acids 4a–4c. A more elaborate scheme to prepare 4d was needed (Scheme 1). The acid 7 was synthesized by a reported procedure27 with slight modifications. Briefly, 1,8-naphthoic anhydride was nitrated by HNO3/H2SO4 followed by mercury-mediated decarboxylation of the resulting anhydride (Pesci reaction) and acidic hydrolysis to give the mono-acid 6. Direct reduction of the nitro group in 6 with iron resulted in only low yield of the corresponding aniline. However, reduction of the methyl ester of 6 gave 95% yield of the corresponding aniline, which was further converted into naphthol 7 through a diazonium salt and concomitant hydrolysis of the methyl ester. The requisite building block 4d was prepared by Mitsunobu reaction followed by saponification (Scheme 1). With all the building blocks 4a–4d in hand, they were each coupled to amine 820 with EDCI/HOBt as the coupling reagents to give Boc-protected amides 9a–9d (Scheme 2). Final removal of Boc protecting group from 9a–9d provided desired compounds 1a–1d in good to excellent yields.28

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of building blocks 4a–4d.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of regioisomers 1a–1d.

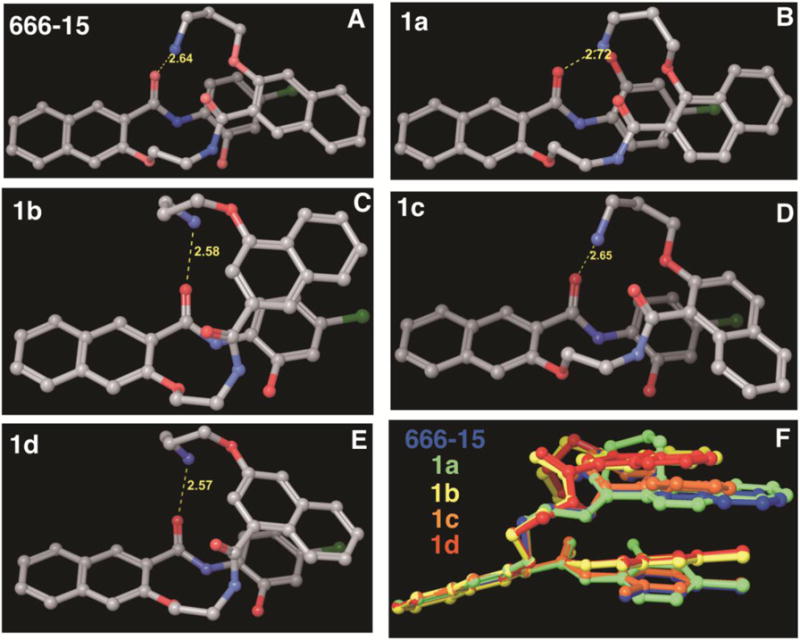

With the designed regioisomers 1a–1d in hand, we first evaluated their potency in inhibiting CREB-mediated gene transcription in living HEK 293T cells using our previously described CREB transcription reporter assay.29 This reporter assay involved transfecting HEK 293T cells with a reporter construct, which expresses renilla luciferase with three tandem copies of CRE sequence in the promoter region to report CREB’s transcription activity in living cells. Then the transfected cells were treated with increasing concentrations of different compounds (50 nM to 50 μM) followed by stimulation with forskolin (10 μM) to stimulate CREB phosphorylation and transcription activity. The relative luciferase activity was used to report CREB’s transcription activity. We have previously shown that 666-15 had an IC50 of ~ 80 nM in this transcription reporter assay.20 As shown in Table 1, moving the aminopropoxy group from position 3 in 666-15 to position 1 (1a, IC50 = 23.98 ± 16.02 μM) or 4 (1b, IC50 = 17.25 ± 3.90 μM) resulted in significantly decreased CREB inhibition activity. Similarly, relocation of the carboxamide from position 2 in 666-15 to 4 (1c, IC50 = 18.94 ± 5.35 μM) or 1 (1d, IC50 = 19.03 ± 10.96 μM) also dramatically attenuated the inhibitory activity. These results show that the substitution pattern on naphthalene ring B is absolutely critical in determining the CREB inhibition activity. Previously, we have shown that 666-15 adopted a compact conformation at its global energy minimum (see also Figure 3A).20 To investigate if the regioisomers 1a–1d also adopt such a compact conformation at their global energy minimum, a conformational search was performed for compounds 1a–1d using the same protocol we did before.20 Similar to 666-15, the positively charged ammonium group in 1a–1d all hydrogen bonded with the carbonyl oxygen (Figure 3B–2E). The naphthalene ring B in 1a–1d also forms π-stacking interaction with the chlorophenyl ring, effectively forming a compact conformation similar to what is observed in 666-15. However, as the substitution pattern in the naphthalene B changes, the relative orientation of the two-carbon linker D and naphthalene ring B vary greatly compared to 666-15 (Figure 3F). These results suggest that the unique arrangement of different groups in 666-15 forming the potential bioactive pharmacophore can not be altered without losing bioactivity.

Table 1.

Biological activities of regioisomer 1a–d.

| compd | IC50 (μM)a | GI50 (μM)b | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| CREB inhibition | MDA-MB-231 | MDA-MB-468 | |

| 666-15 | 0.081 ± 0.04 | 0.073 ± 0.04 | 0.046 ± 0.04 |

| 1a | 23.98 ± 16.02 | 3.12 ± 0.13 | 1.93 ± 0.06 |

| 1b | 17.25 ± 3.90 | 2.68 ± 0.06 | 0.55 ± 0.16 |

| 1c | 18.94 ± 5.35 | 4.31 ± 0.73 | 1.70 ± 0.03 |

| 1d | 19.03 ± 10.96 | 3.82 ± 0.95 | 1.65 ± 0.53 |

The CREB inhibition refers to the activity of the compounds in the CREB transcription reporter assay in HEK 293T cells. The cells were transfected with a renilla luciferase reporter under the control of three copies of CRE. Then the cells were treated with increasing concentrations of different compounds for 30 min followed by stimulation with forskolin (10 μM) for 6 h before luciferase measurement. The IC50 was calculated through non-linear regression analysis of the dose-response curves with normalized luciferase activity. The normalization was carried out through the cell lysate protein concentration in individual samples.

The GI50 was from the MTT assay after incubating the drugs with the indicated cells for 72 h. The activities of 666-15 are included for comparison purpose and are from reference20.

Figure 3.

Global conformational energy minima of 666-15 (A), 1a (B), 1b (C), 1c (D) and 1d (E). The yellow dotted line indicates a hydrogen bond and the corresponding interatomic distance is shown in Å. In panel (F), the conformations of 1a–1d are superimposed onto that of 666-15.

We also assessed the cancer cell growth inhibition activities of 1a–1d in breast cancer MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cells. As shown in Table 1, all four regioisomers show significantly less potent activity than 666-15. These results are consistent with their reduced potency in inhibiting CREB-mediated gene transcription. However, distinct differences exist for 1a–1d between the two different assays. The growth inhibitory activity of 1a–1d in these breast cancer cell lines is in general higher than their CREB inhibition potency. This difference suggests that 1a–1d may be endowed with activities independent of CREB inhibition in the cells. This possibility is likely because the conformations accessible for 1a–1d can be dramatically different from those of 666-15 due to the differential substitution pattern in naphthalene ring B.

In this study, we designed, synthesized and evaluated regioisomers of 666-15, a potent CREB inhibitor with robust anti-breast cancer efficacy without harming normal body homeostasis. Our results showed that the alkoxy and carboxamide substitution pattern in naphthalene ring B of 666-15 is absolutely critical for maintaining potent CREB inhibition and anti-proliferative activity in breast cancer cells. These results reinforced that the unique bioactive conformation accessible only in 666-15 is the key for its potent activity. Further studies of SAR of 666-15 should keep this unique pharmacophore intact.

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible through financial supports provided by National Institutes of Health (R01 GM087305) and OHSU Office of Technology Transfer and Business Development.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.Meacham CE, Morrison S. J Nature. 2013;501:328–337. doi: 10.1038/nature12624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higgins MJ, Baselga J. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3797–3803. doi: 10.1172/JCI57152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lackner MR, Wilson TR, Settleman J. Future Oncol. 2012;8:999–1014. doi: 10.2217/fon.12.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riggins RB, Schrecengost RS, Guerrero MS, Bouton AH. Cancer Lett. 2007;256:1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinstein JN, Collisson EA, Mills GB, Shaw KR, Ozenberger BA, Ellrott K, Shmulevich I, Sander C, Stuart JM. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1113–1120. doi: 10.1038/ng.2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeh JE, Toniolo PA, Frank DA. Curr Opin Oncol. 2013;25:652–658. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000432528.88101.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaywitz AJ, Greenberg ME. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:821–861. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayr B, Montminy M. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:599–609. doi: 10.1038/35085068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiao X, Li BX, Mitton B, Ikeda A, Sakamoto KM. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2010;10:384–391. doi: 10.2174/156800910791208535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johannessen M, Moens U. In: Trends in Cellular Signaling. Caplin DE, editor. Nova Publishers, Inc.; 2006. pp. 41–78. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagiwara M, Alberts A, Brindle P, Meinkoth J, Feramisco J, Deng T, Karin M, Shenolikar S, Montminy M. Cell. 1992;70:105–113. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90537-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wadzinski BE, Wheat WH, Jaspers S, Peruski LF, Lickteig RL, Johnson GL, Klemm DJ. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2822–2834. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.5.2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu T, Zhang Z, Wang J, Guo J, Shen WH, Yin Y. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2821–2825. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodon L, Gonzalez-Junca A, Inda MD, Sala-Hojman A, Martinez-Saez E, Seoane J. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:1230–1241. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang S, Chen L, Cui B, Chuang H-Y, Yu J, Wang-Rodriguez J, Tang L, Chen G, Basak GW, Kipps T. J PLoS One. 2012;7:e31127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Sligte NE, Kampen KR, ter Elst A, Scherpen FJ, Meeuwsen-de Boer TG, Guryev V, van Leeuwen FN, Kornblau SM, de Bont ES. Oncotarget. 2015;6:14970–14981. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang M, Li BX, Xie F, Delaney F, Xiao X. J Med Chem. 2012;55:4020–4024. doi: 10.1021/jm300043c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li BX, Xie F, Fan Q, Barnhart KM, Moore CE, Rheingold AL, Xiao X. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2014;5:1104–1109. doi: 10.1021/ml500330n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li BX, Yamanaka K, Xiao X. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20:6811–6820. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.09.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie F, Li BX, Kassenbrock A, Xue C, Wang X, Qian DZ, Sears RC, Xiao X. J Med Chem. 2015;58:5075–5087. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie F, Li BX, Xiao X. Lett Org Chem. 2013;10:380–384. doi: 10.2174/1570178611310050014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie F, Li BX, Broussard C, Xiao X. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:5371–5375. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.07.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lodge JM, Rettenmaier TJ, Wells JA, Pomerantz WC, Mapp AK. MedChemComm. 2014;5:370–375. doi: 10.1039/C3MD00356F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JW, Park HS, Park SA, Ryu SH, Meng W, Jurgensmeier JM, Kurie JM, Hong WK, Boyer JL, Herbst RS, Koo JS. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122628. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitton B, Chae HD, Hsu K, Dutta R, Aldana-Masangkay G, Ferrari R, Davis K, Tiu BC, Kaul A, Lacayo N, Dahl G, Xie F, Li BX, Breese MR, Landaw EM, Nolan G, Pellegrini M, Romanov S, Xiao X, Sakamoto KM. Leukemia. 2016 doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.1139. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li BX, Gardner R, Xue C, Qian DZ, Xie F, Thomas G, Kazmierczak SC, Habecker BA, Xiao X. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34513. doi: 10.1038/srep34513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duffy KJ, Darcy MG, Delorme E, Dillon SB, Eppley DF, Erickson-Miller C, Giampa L, Hopson CB, Huang Y, Keenan RM, Lamb P, Leong L, Liu N, Miller SG, Price AT, Rosen J, Shah R, Shaw TN, Smith H, Stark KC, Tian SS, Tyree C, Wiggall KJ, Zhang L, Luengo JI. J Med Chem. 2001;44:3730–3745. doi: 10.1021/jm010283l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The characterization data are below. 1a: a white solid. m.p.221–222 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ11.02 (s, 1 H), 10.52 (s, 1 H), 8.75 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 1 H), 8.73 (s, 1 H), 8.43 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1 H), 8.15−8.10 (m, 1 H), 8.06 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 8.00−7.95 (m, 4 H),7.94 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.74 (s, 1 H), 7.70 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1 H), 7.64−7.56 (m, 4 H), 7.46 (td, J = 7.5, 1.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.05 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1 H), 6.89 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.3 Hz, 1 H), 4.54 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 1 H), 4.12 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 2 H), 4.00 (q, J = 6.1 Hz, 2 H), 4.03 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 2 H), 3.04−2.94 (m, 2 H), 2.12 (quintet, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 167.35, 162.58, 153.63, 152.92, 148.38, 136.12, 135.61, 133.60, 129.40, 129.02, 128.46, 128.19, 128.09, 127.86, 127.53, 127.24, 126.97, 126.69, 126.31, 125.29, 124.96, 124.16, 123.01, 123.00, 121.49, 119.19, 114.93, 108.84, 73.30, 67.93, 38.91, 36.91, 28.16. 1b: a white solid, m.p. 198–199 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.03 (s, 1 H), 10.57 (s, 1 H), 8.90 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1 H), 8.74 (s, 1 H), 8.42 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1 H), 8.20−8.16 (m, 1 H), 8.05 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1 H), 8.03−7.96 (m, 4 H), 7.91 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.87−7.83 (m, 1 H), 7.74 (s, 1 H), 7.62−7.56 (m, 3 H), 7.45 (td, J = 7.5, 1.1 Hz, 1 H), 7.33 (s, 1 H), 6.97 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1 H), 6.88 (d, J = 8.9, 2.6 Hz, 1 H), 4.55 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 2 H), 4.24 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 2 H), 3.96 (q, J = 5.5 Hz, 2 H), 3.07 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2 H), 2.18 (quintet, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 167.31, 162.61, 154.27, 153.62, 148.28, 136.12, 133.60, 133.48, 132.47, 129.38, 129.07, 129.00, 128.17, 127.66, 127.54, 127.45, 126.92, 126.68, 126.50, 125.26, 123.05, 122.02, 121.60, 120.31, 119.26, 14.90, 108.87, 103.75, 67.86, 65.52, 38.98, 36.88, 27.35. 1c: a white solid. m.p. 180–181 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.99 (s, 1 H), 10.53 (s, 1 H), 8.76 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 1 H), 8.74 (s, 1 H), 8.44 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1 H), 8.06 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.98−7.93 (m, 2 H), 7.91−7.82 (m, 4 H), 7.72 (s, 1 H), 7.67 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1 H), 7.61 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1 H), 7.49−7.43 (m, 2 H), 7.32 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.17 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.04 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1 H), 6.90 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.3 Hz, 1 H), 4.58 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 2 H), 4.23 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 2 H), 4.02 (q, J = 5.5 Hz, 2 H), 2.96 (q, J = 5.9 Hz, 2 H), 1.98 (quintet, J = 6.5 Hz, 2 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 167.45, 162.54, 153.75, 152.46, 148.34, 136.14, 133.63, 131.16, 130.64, 129.41, 129.02, 128.73, 128.30, 128.15, 127.44, 127.32, 127.00, 126.74, 125.26, 124.42, 124.35, 122.95, 122.33, 121.42, 119.18, 115.46, 114.90, 108.69, 67.93, 66.62, 39.02, 36.83, 27.34. 1d: a white solid. m.p. 145–146 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.00 (s, 1H), 10.59 (s, 1H), 8.85 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 8.74 (s, 1H), 8.45 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 8.11 − 8.03 (m, 2H), 8.00 (brs, 3H), 7.92 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (s, 1H), 7.60 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.49 − 7.42 (m, 2H), 7.39 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.25 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.21 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 6.99 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.90 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 4.57 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 4.15 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 3.99 (q, J = 5.3 Hz, 2H), 2.97 (q, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 2.06 (quintet, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 168.70, 162.56, 155.36, 153.78, 148.30, 136.57, 136.13, 135.02, 133.62, 129.42, 129.04, 128.14, 127.51, 127.45, 127.15, 126.90, 126.73, 125.80, 125.72, 125.24, 124.67, 122.98, 121.47, 119.22, 118.41, 114.84, 109.18, 108.68, 67.94, 65.33, 39.13, 36.73, 27.21

- 29.Li BX, Xiao X. Chembiochem. 2009;10:2721–2724. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]