SUMMARY

BACKGROUND

While the results of a recent meta-analysis using the traditional random-effects model yielded a statistically significant standardized mean difference (SMD) reduction in cancer-related fatigue (CRF) as a result of aerobic exercise, a recently developed inverse heterogeneity (IVhet) model has been shown to be more valid than the traditional random-effects model. The purpose of this study was to compare these previous meta-analytic results using the IVhet model.

METHODS

Using data from a previous meta-analysis that included 36 SMD effect sizes (ES’s) representing 2,830 adults (1,426 exercise, 1,404 control), results were pooled using the IVhet model. Absolute and relative differences between the IVhet and random-effects results for CRF were also calculated as well as influence analysis with each SMD ES deleted from the IVhet model. Non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A statistically non-significant reduction in CRF fatigue was found as a result of aerobic exercise using the IVhet model (SMD, −0.08, 95% CI, −0.31 to 0.14, p = 0.46). The IVhet model yielded a SMD ES that was 0.14 (63.6%) smaller than the random-effects model. With each study deleted from the IVhet model once, results remained statistically non-significant with SMD ES’s ranging from −0.11 (95% CI, −0.33 to 0.11) to −0.06 (95% CI, −0.28 to 0.16).

CONCLUSIONS

Insufficient evidence currently exists to support the use of aerobic exercise for reducing CRF in adults.

IMPACT

Additional studies are needed to determine the certainty of aerobic exercise on CRF in adults.

Keywords: exercise, cancer, fatigue, adults, meta-analysis, methods

Introduction

One of the most significant side-effects of cancer treatment is cancer-related fatigue (CRF) (1, 2), a condition that is highly prevalent both during and after treatment (1). The most recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials to date reported a statistically significant standardized mean difference (SMD) reduction on CRF as a result of aerobic exercise in adults (SMD, −0.22, 95% CI, −0.39 to −0.04, p = 0.01) (3). While these findings are encouraging, they were based on the most commonly used random-effects model of Dersimonian and Laird (4), a model that has been shown to be less accurate than the recently developed inverse heterogeneity (IVhet) model (5). The purpose of this brief report was to use the IVhet model (5) to examine the effects of aerobic exercise on CRF and compare these findings with previous meta-analytic results based on the random-effects model (3).

Material and methods

Data Source

Data for the current brief report were derived from the most recently reported meta-analysis on exercise and CRF in adult cancer patients and survivors, details of which have been described elsewhere (3). Briefly, randomized controlled trials of aerobic exercise representing 36 SMD effect sizes for CRF from 26 studies that included 2,830 adults (1,426 exercise, 1,404 control) were pooled using the IVhet model (3).

Data Synthesis

Effect size calculations

The effect sizes pooled for the current study were extracted from previously reported SMD results on aerobic exercise and CRF (3).

Effect size pooling

The recently developed IVhet model was used to pool each SMD on aerobic exercise and CRF in adults, details of which have been described elsewhere (5). This quasi-likelihood model is produced by calculating weights that sum to 1 from each study, pooling the effects from all studies, and then calculating the variance of the pooled effect sizes. The IVhet model has been shown to be more valid then the original random-effects, method-of-moments model of Dersimonian and Laird (5), the most commonly used model for pooling aggregate data meta-analytic results (6).

The pooled results for CRF derived from the IVhet were then compared to those previously calculated (3) using the original random-effects method-of-moments model of Dersimonian and Laird (4). In addition, Q and I2 statistics for heterogeneity and inconsistency were calculated as well as influence analysis with each study deleted from the model once. For I2, inconsistency was considered to be very low (<25%), low (25% to <50%), moderate (50% to <75%) or large (≥ 75%) (7). All analyses were conducted using the same data and partitioning of effect sizes as reported in the original meta-analysis (3). Data were analyzed using Meta XL (version 5.3) (8).

Results

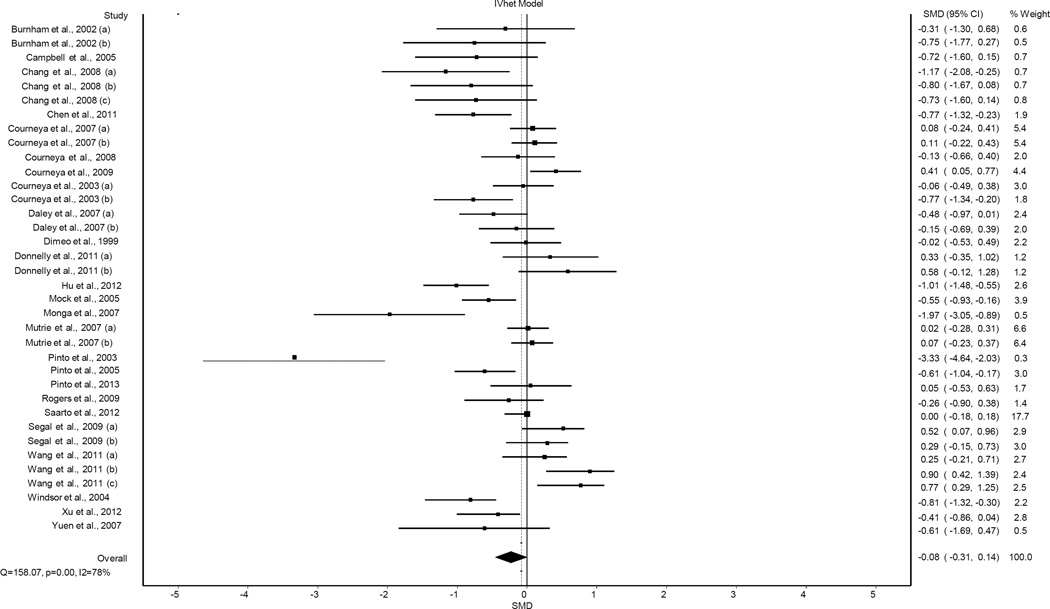

A total of 36 SMD effect sizes (ES’s) representing 2,830 adults 18 years of age and older (1,426 exercise, 1,404 control), were pooled from the previous meta-analysis (3). Results for changes in CRF using the IVhet model are shown in Figure 1. As can be seen, results were not statistically significant using the IVhet model (SMD, −0.08, 95% CI, −0.31 to 0.14, p = 0.46). Statistically significant heterogeneity (Q = 158.1, p <0.001) and a large amount of inconsistency (I2 = 78.0%, 95% CI, 69.8% to 83.8%) were observed. IVhet model results yielded a SMD that was 0.14 (63.6%) smaller than the random-effects model. With each study deleted from the model once, SMD results remained statistically non-significant across all deletions, ranging from −0.11 (95% CI, −0.33 to 0.11) to −0.06 (95% CI, −0.28 to 0.16).

Figure 1.

Forest plot for changes in CRF using the IVhet model. The black squares represent the standardized mean difference (SMD) effect size while the left and right extremes of the squares represent the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. The middle of the black diamond represents the overall SMD while the right and left extremes of the diamond represent the corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

The results of the current study suggest that caution may be warranted regarding the benefits of exercise on CRF. This is important since meta-analyses are often used to make decisions about the usefulness of an intervention such as aerobic exercise on an outcome such as CRF. The former notwithstanding, the current findings should be viewed with respect to the following potential limitations. First, since the current findings were based on aggregate data, there is the potential for ecological fallacy. Second, there was significant heterogeneity and inconsistency regardless of the model used. Consequently, there may be some subgroups in which CRF may improve as a result of aerobic exercise while others do not (3). However, use of the IVhet model for subgroup analyses (type of cancer, method of CRF assessment, exercise characteristics, etc.) was not possible because summary data from each included study based on these characteristics was not available in the original meta-analysis (3). Nevertheless, because studies are not randomly assigned to subgroups in meta-analysis, they are considered to be observational in nature. Therefore, the results of any subgroup analyses conducted in an aggregate data meta-analysis do not support causal inferences. In addition, multiple subgroup analyses increase the risk for chance findings.

Conclusions

A lack of convincing evidence exists to support the use of aerobic exercise for reducing CRF in adults.

Acknowledgments

Funding

G.A. Kelley and K.S. Kelley were supported by a grant received by S. Hodder from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (grant number U54 GM104942). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The authors would like to thank S. Hodder for the support of this work.

Footnotes

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hofman M, Ryan JL, Figueroa-Moseley CD, Jean-Pierre P, Morrow GR. Cancer-related fatigue: the scale of the problem. Oncologist. 2007;12(Suppl 1):4–10. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Cancer-related fatigue. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tian L, Lu HJ, Lin L, Hu Y. Effects of aerobic exercise on cancer-related fatigue: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(2):969–983. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2953-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dersimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doi SA, Barendregt JJ, Khan S, Thalib L, Williams GM. Advances in the meta-analysis of heterogeneous clinical trials I: The inverse variance heterogeneity model. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45(Pt A):130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dersimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials revisited. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45(Pt A):139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meta XL. Queensland, Australia: EpiGear International Pty Ltd; 2016. [Google Scholar]