Abstract

Regulatory T (Treg) cells establish tolerance, prevent inflammation at mucosal surfaces, and regulate immunopathology during infectious responses. Recent studies have shown that Delta-like ligand 4 (Dll4) was up-regulated on antigen presenting cells after RSV infection and its inhibition leads to exaggerated immunopathology. The present studies outline the role of Dll4 in Treg cell differentiation, stability and function in RSV infection. Here we found that Dll4 was expressed on CD11b+ pulmonary DC in the lung and draining lymph nodes in wild type BALB/c mice after RSV infection. Dll4 neutralization exacerbated RSV-induced disease pathology, mucus production, group 2 innate lymphoid cell (ILC2) infiltration, IL-5 and IL-13 production, as well as IL-17A+ CD4 T cells. Dll4 inhibition decreased the abundance of CD62LhiCD44loFoxp3+ central Treg cells (cTR) in draining lymph nodes. The RSV-induced disease was accompanied by an increase in Th17-like effector phenotype in Foxp3+ Treg cells and a decrease in Granzyme B expression after Dll4 blockade. Finally, Dll4-exposed induced Treg (iTreg) cells maintained CD62LhiCD44lo cTR cell phenotype, had increased Foxp3 expression, became more suppressive, and were resistant to Th17 skewing in vitro. These results suggest that Dll4 activation during differentiation sustained Treg cell phenotype and function to control RSV infection.

Introduction

Notch is a highly conserved signaling pathway that contributes to cell differentiation and function. Engagement of Notch receptors (Notch 1-4) and Notch ligands (Delta-like ligand 1, 3, 4, Jagged 1, 2) initiates cleavage of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD). NICD binds to recombination binding protein-J (RBP-Jκ) and activates the transcription of Notch target genes in association with a co-activator of the Mastermind like family (MAML 1-3). Notch signaling regulates various stages of T cells lineage development and differentiation, including early stages of thymocyte development, as well as CD4 T helper (Th) differentiation (1, 2). In the priming stage of Th cell differentiation, Notch ligand Dll4 sensitized antigen responses and augmented T cells activation (3), while separate studies demonstrated that Dll4 and Notch could activate production of IFNγ and the Th1 transcription factor T-bet (4–6). During Th2 differentiation, Jagged1 and intracellular Notch promoted Gata3 and Il4 expression (4, 7, 8), while Dll4 suppressed Il4, Il5, and Il13 (9, 10). Furthermore, Dll4 and Notch was reported to promote Th17 and Th9 differentiation by enhancing Il17a, Rorc and Il9 expression (11, 12). Together, Notch can serve as an amplifier for persistent Th1, Th2, and Th17 cell differentiation (5), suggesting that it is not a skewing signal, but rather enhances co-activation. However the role of Dll4 and Notch signaling in Treg cells remains unresolved. Jagged2 and specific receptors, Notch1 and Notch3, promoted the Treg cell master transcription factor—Foxp3 expression and Treg cell survival (13–17), and RBP-Jκ was reported to directly bind the Foxp3 promoter and regulate Foxp3 transcription (17). In contrast, inactivating Notch signaling after Foxp3 is expressed enhanced Treg cell numbers and promoted tolerance (18). Blockade of Notch receptors and Notch ligands expanded Foxp3+ T cell populations in vivo in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), Graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), and Type 1 diabetes (T1D) (19–22). However, the role of Notch ligands in Treg cell development and their resistance to inflammation during infection has not been well-defined.

Notch ligands can be induced on antigen presenting cells by pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) (4, 7). Pathogens themselves can also induce Notch ligands. Studies showed that Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) induced Dll4 expression on dendritic cells in vitro (9, 23), and Dll4 blockade exacerbated RSV-induced Th2 airway pathogenesis (9). Since Treg cells are required to limit pulmonary inflammation and pathogenic Th2 responses during RSV infections (24–26), we hypothesized that initial exposure of Dll4 may modulate peripherally-induced Treg (iTreg) cell differentiation, homeostasis and stability to control the intensity of the immune response and lung pathology during RSV infection. In the present study, we report that Dll4 sustained CD62LhiCD44lo central Treg cells and solidified iTreg cell identity during infection. This study defines novel roles of Dll4 in iTreg cell subset regulation and iTreg cell stability.

Materials and Methods

Mice

6-8 week old female BALB/cJ and C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. Female CD45.1 (B6-Ly5.1/Cr) mice were purchased from Charles River. Foxp3eGFP mice (B6.Cg-Foxp3tm2(EGFP)Tch/J, stock number 006772) were bought from Jackson Laboratory and bred in house. CD4-specific DNMAML mice (Cd4-Cre × R26DNMAMLf) and CD4-specific Rbpj knockout mice (Cd4-Cre × Rbpjf/f) are generated as described (27–29). All mice were housed in the University Laboratory Animal Facility under animal protocols approved by the Animal Use Committee in University of Michigan.

RSV infection and In vivo neutralization of Dll4

RSV Line 19 was clinical isolate originally from a sick infant in University of Michigan Health System to mimic human infection (30). BALB/cJ mice were anesthetized and infected intratracheally (i.t) with 1 × 105 pfu of Line 19 RSV, as previously described (9). For Dll4 blockade in vivo, 2.5 mg of purified polyclonal anti-Dll4 antibody or control IgG were injected intraperitoneally (i.p) two hours before RSV infection at day 0. Same dose of control or anti-Dll4 antibody were given on day 2, 4, and 6.

Histopathology

Left lobe of lung was fixed with 4% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin, and 5 μm of section were stained with Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain to detect mucus.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative PCR

RNA were extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen) by following manufacturers protocol, and one μg of total RNA were reverse transcribed to cDNA to determine gene expression using Taqman gene expression primer/probe sets. Dll1, Dll4, Jag1, and Jag2 were detect by SYBR as described (31). Delta4 primers: 5’-AGGTGCCACTTCGGTTACACAG-3’ and 5’-CAATCACACACTCGTTCCTCTCTTC-3’. Muc5ac and Gob5 expression were assessed by custom primers as described (32). Detection was performed in ABI 7500 Real-time PCR system. Gene expression was calculated using the ΔΔCt method and normalized with Gapdh as input control.

Primary cells Isolation and Cytokine production assay

Mice lungs were chopped. Lung and mediastinal lymph node were enzymatically digested using 1 mg/mL Collagenase A (Roche) and 25 U/ml DNaseI (Sigma-Aldrich) in RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal calf serum for 45 min at 37°C. Tissue were further dispersed through 18 gauge needle/10 mL syringe, and filtered through 100-μm nylon mesh twice. 5 × 105 cells from mediastinal lymph node cells were plated in 96-well and re-stimulated with 105 pfu RSV Line 19 for 48 hours. IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-17A, IL-10, IL-9 level in supernatant were measured with Bio-plex™ cytokine assay (Bio-Rad).

Extracellular and Intracellular Flow cytometry analysis

Single-cell suspension of lung and lymph node were stimulated with 100 ng/mL Phorbol-12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), 750 ng/mL Ionomycin, 0.5 μL/mL GolgiStop (BD), 0.5 μL/mL GolgiPlug (BD) for 5 hours if mentioned. After excluding dead cells with LIVE/DEAD Fixable Yellow stain (Invitrogen), cells were pre-incubated with anti-FcγR III/II (Biolegend) for 15 minutes and labeled with the following antibody from Biolegend, unless otherwise specified: anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), CD3 (145-2C11), CD4 (GK1.5), CD8α (53-6.7), CD11b (M1/70), CD11c (N418), CD25 (PC61), CD44 (IM7), CD45 (30-F11), CD62L (MEL-14), CD69 (H1.2F3), CD103 (2E7), CD127 (SB/199), CCR7 (4B12), Dll1 (HMD1-3), Dll4 (HMD4-1), Gr-1 (RB6-8C5), I-A/I-E (M5/114.15.2), ST2 (DIH9). For Innate lymphoid cells staining, Lineage markers were anti-CD3, CD11b, B220, Gr-1, TER119. After 30 minutes of incubation at 4°C, cells were washed and proceed to intracellular staining.

For intracellular staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized with Transcription factors staining buffer set (eBioscience). Cells were labeled with antibody from eBioscience: Foxp3 (FJK-16s), IL-17A (eBio17B7), IL-13 (eBio13A), GATA3 (TWAJ), RORγt (AFKJS-9), GzmB (NGZB) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Flow cytometry data were acquired from LSR II (BD) or Novocyte (ACEA) flow cytometer and were analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Naïve CD4 T Cell Isolation and Stimulation

CD4+CD25−CD62LhiCD44lo naïve T cells were enriched from spleen using the naïve CD4 T cells isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) with more than 92% purity. Naïve T cells were then plated and cultured in 24-well plates. 106 / 0.5 mL of naïve T cells were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 (2.5 μg/mL; eBioscience), soluble anti-CD28 (3 μg/mL; eBioscience), and plate-bound recombinant Dll4 (1.65 μg/mL or the dose mentioned; R&D); to skew toward in vitro-induced Treg cells (iTreg), human TGFβ1 (2 ng/mL; R&D System) and mouse IL-2 (10 ng/mL; R&D System) were added at the same time; to re-stimulate toward in vitro-induced Th17 cells (Th17), mouse IL-6 (10 ng/mL; R&D System), human TGFβ1 (2 ng/mL; R&D System), anti-IFNγ neutralizing antibody (10 μg/mL; eBioscience), anti-IL-4 neutralizing antibody (10 μg/mL; eBioscience), and anti-IL-12/23 p40 neutralizing antibody (10 μg/mL; eBioscience) were added at 5 × 105/ 0.2 mL of viable iTreg culture or 105/ 0.2 mL sorted eGFP+ iTreg if mentioned.

Cell sorting and In vitro suppression assay

Single cell sorting was performed on FACSAria II (BD). DAPI−CD4+eGFP+ viable Treg were sorted with more than 93% efficiency. Suppression assay was performed as described with small modification (33). In brief, naïve T cells isolated from CD45.1 mice were labeled with Cell Trace Violet (CTV) (Invitrogen). 2.5 × 104 of labeled CD45.1+ naïve T cells were co-cultured with serial-diluted eGFP+ Treg in 96 well round bottom plate. 0.625 μL of Dynabeads® mouse T activator CD3/CD28 (Invitrogen) were added to 0.2 mL of culture. After 72 hours, cells were harvested, and CD45.1+ responder cell proliferation were accessed by CTV dilution.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by Prism6 (GraphPad). Data presented are mean values ± SEM. Comparison of two groups was performed in unpaired, two-tailed, Student’s t-test. Comparison of three or more groups was analyzed by ANOVA with Tukey’s post-tests. Significance was indicated at the level of *:p<0.05, **: p<0.005, ***: p<0.0005

Results

Up-regulation of Dll4 during RSV infection on CD11b+ pulmonary DC

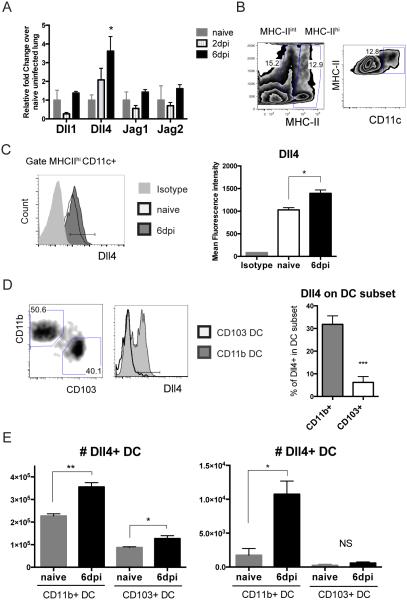

Previously published data have shown that Dll4 expression was up-regulated on dendritic cells post RSV infection in vitro (9, 23). To further characterize the expression of Dll4 during RSV infection in vivo, BALB/cJ mice were intratracheally (i.t.) infected with 1 × 105 pfu of RSV before harvesting of lung tissues at 2 and 6 days post infection (dpi). Delta-like ligand 4 (Dll4) transcripts were up-regulated significantly at 6 dpi, while transcripts for the other Notch ligands Dll1, Jagged (Jag) 1 and Jag2, were not increased in the lung (Fig 1A). After gating on MHChi CD11c+ dendritic cells (Fig 1B), Dll4 expression level was increased consistently on MHCIIhi CD11c+ dendritic cells after 6 dpi (Fig 1C). To further understand which type of DC expressed Dll4 after RSV infection, two populations of pulmonary dendritic cells (DC) were identified to determine Dll4 expression: MHCIIhi CD11c+ CD11b+ CD103− DC and MHCIIhi CD11c+ CD103+ CD11b− DC. CD11b+ DC expressed Dll4, whereas few of the CD103+ DC expressed Dll4 during RSV infection (Fig 1D). When we examined the number of DC in lung and draining lymph node at 6 dpi, increasing numbers of Dll4+ CD11b+ DC in both lung and mediastinal lymph node (mLN) were detected as the infection progressed. In contrast, the number of Dll4+ CD103+ DC was significantly lower and variable in lung or mLN after infection (Fig 1E). These data indicated that Dll4 was expressed on pulmonary DC, especially CD11b+ DC, after RSV infection in vivo.

Figure 1. Dll4 expresses on CD11b+ pulmonary DC during RSV infection.

A. Abundance of Dll1, Dll4, Jag1, and Jag2 mRNA in RSV-infected lung at the indicated time points relative to uninfected naïve lung

B. Representative flow cytometric analysis showing the gating strategy of viable MHC-II hi CD11c+ dendritic cells (DC) in RSV-infected lung at 6 dpi

C. Representative flow cytometric analysis showing the mean fluorescence intensity of Dll4 on Dll4+ MHC-II hi CD11c+ DC from RSV-infected lung

D. Percent of Dll4+ in CD11b+ or CD103+ DC (left, gating strategy) from infected lung

E. Numbers of Dll4+ CD11b+ DC or Dll4+ CD103+ DC in the lungs (left) or draining mediastinal lymph nodes (mLN) (right) of naïve or RSV-infected mice.

Data represent mean ± s.e.m. Data were from one experiment representative of two experiments with 4 to 5 mice per time point, with samples from each mouse processed and analyzed separately. * P<0.05; ** P<0.005; *** P<0.0005; NS: no significance (unpaired two-tailed t-test)

Inhibition of Dll4 exacerbated RSV-induced immunopathology in vivo

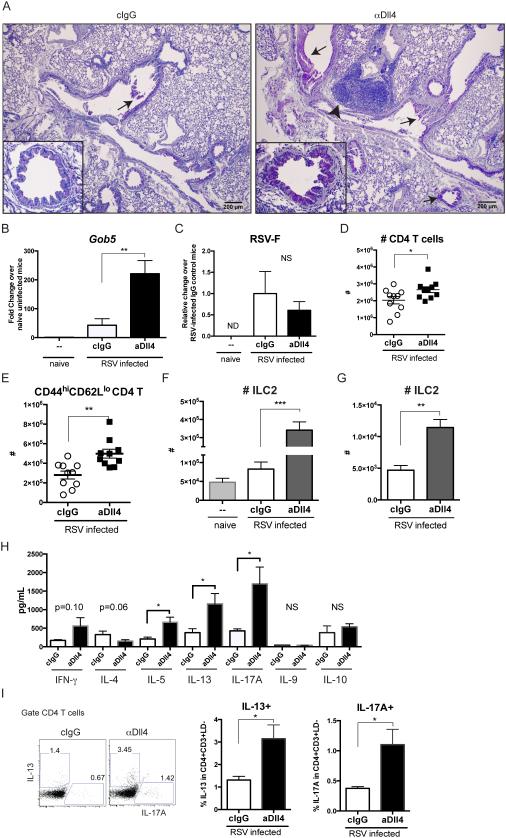

Next, we explored the role of Dll4 in controlling RSV immunopathology by blocking Dll4 in vivo during RSV infection. We have previously demonstrated that our polyclonal anti-Dll4 antibody is specific for Dll4 and not other Notch ligands (9). The polyclonal anti-Dll4 antibody decreased the abundance of Notch target gene Hes1 transcripts in activated T cells (Th0) in co-culture with fixed Dll4-expressing stromal cells (Sup Fig 1A), indicating that anti-Dll4 antibody blocked Dll4-mediated Notch activation in vitro. We next aimed at blocking Dll4 in vivo by injecting 2.5 mg of purified anti-Dll4 antibody intraperitoneally (i.p). Mice were then infected intratracheally (i.t) with RSV 2 hours after antibody injection at day 0, followed by i.p injection of anti-Dll4 every other day. After 8 days, the abundance of Hey1—Notch target gene transcripts was decreased in the lung (Sup Fig 1B) and sorted CD4 T cells (Sup Fig 1C) of anti-Dll4-treated mice, suggesting that systemic administration of anti-Dll4 antibodies inhibited Notch signaling activation in CD4 T cells in vivo. Dll4 blockade increased peribronchial infiltration by mononuclear cell clusters and drove mucus production in the airway as assessed in periodic-acid Schiff (PAS)-stained lung sections (Fig 2A). As an indication of RSV-induced pathology, expression of the mucus-associated gene gob5 (mClca3) was substantially increased (Fig 2B), but the viral protein mRNA expression measured with RSV-F and RSV-G were not significantly different at either 6 dpi or 8 dpi (Fig 2C and data not shown). While Dll4 inhibition increased total CD4 T as described (Fig 2D) (9), data also showed that more CD4 T cells acquired a CD44hiCD62Llo effector phenotype (Fig 2E). Another activation marker CD25 was not changed in CD4 T cells at 8 dpi (data not shown). Thus, Dll4 inhibition significantly altered lung immunopathology during RSV infection. Besides CD4 T cells, RSV infection can also expand group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) between 4 to 6 dpi in lung to be mucogenic and immunopathogenic (34). Here we investigate if Notch ligand Dll4 affects ILC2 homeostasis. Strikingly, Dll4 inhibition increased the number of Lin-CD45+CD127+CD90.2+ST2+CD25+ ILC2 in lung (Fig 2F) and mLN (Fig 2G) at 6 dpi. Thus, Dll4 blockade increased ILC2 in the lungs during RSV infection.

Figure 2. Blockade of Dll4 drives mucus production, accumulation of activated CD4 T cells, group 2 innate lymphoid cells, and cytokine production.

A. Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining of formalin-fixed lung section from 8 dpi. Bar, 200 μm. ↑ indicates the detection of mucin, and ˄ designates mononuclear cells aggregates.

B. Gob5 expression in the lung at 8 dpi.

C. RSV-F viral protein expression in lung at 8 dpi. ND: non-detectable.

D. Numbers of CD4 T cells in lung at 8dpi.

E. Numbers of CD44hiCD62Llo effector CD4 T cells in lung at 8 dpi.

F. Numbers of Group 2 Innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) in lung at 6 dpi.

G. Numbers of ILC2 in mLN at 6 dpi.

H. mLN cells were isolated from mice at 8 dpi and subject to RSV re-stimulation for 48 hours. Indicated cytokines in supernatant were measured.

I. mLN cells were isolated from mice at 8 dpi and re-stimulated with PMA and Ionomycin for 5 hours. Viable CD4 T cells were gated, and intracellular IL-13 and IL-17A were stained.

Data represent mean ± s.e.m. N=7~10 each group. Each symbol represents individual mouse processed and analyzed separately. Data are representative of at least two experiments * P<0.05; ** P<0.005; *** P<0.0005; NS: no significance (unpaired two-tailed t-test)

Excessive cytokine production is one of the key features leading to RSV pathogenesis. The IFNγ promotes viral clearance while IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 and IL-17A are pathogenic (35–37). Here we determined the effect of Dll4 blockade on cytokine profiles in draining lymph nodes. Equal numbers of mLN cells were cultured and re-stimulated with 105 pfu RSV. In vivo Dll4 blockade during RSV infection led to significantly increased Th2 cytokines IL-5 and IL-13 as well as IL-17A while IFNγ, IL-4, IL-9, and IL-10 were not significantly affected in RSV re-challenged lymph node cells (Fig 2H). To specify if Dll4 regulated T helper cell cytokine production in CD4 T cells, mLN cells were re-stimulated with PMA + Ionomycin and CD4 T cells were examined by flow cytometry. Dll4 blockade significantly increased IL-13+ and IL-17A+ CD4 helper T cells in mLN in both 6 dpi and 8 dpi (Fig 2I and data not shown). These data indicated that Dll4 neutralization exacerbated RSV-induced immunopathology, as shown by elevated mucus production, activated CD4 T cells, and Th2-Th17 cytokine over-production.

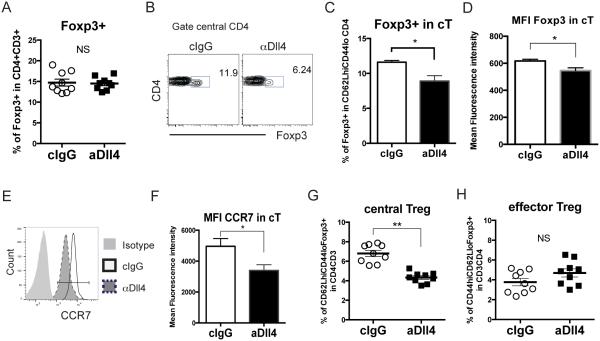

Dll4 neutralization reduces central Treg and increases Th17-like Treg cells during RSV infection

Several studies demonstrated that Treg cells quickly accumulate in lymphoid tissues and in the airway to dampen activated T cell infiltration and Th2 responses (24, 25, 38), and RSV infection drove Treg cells to Th2-like effector cells with impaired function (39). Our group showed that Dll4 inhibition exacerbated type 2 cytokine production and activated T cells infiltration, but little is known about the role of Dll4 in Treg cell development, stability and function. After targeting Dll4 as previously described, total Treg cells did not change in mLN at 6 dpi (Fig 3A). However, when gating on CD62LhiCD44lo central CD4 T cells (cT) (Fig 3B), Dll4 inhibition decreased Foxp3+ cell frequency and expression (Fig 3C, D), while decreasing expression of the CCR7 chemokine receptor on cT cells (Fig 3E, F). CCR7-mediated signals recruit CD62LhiCD44lo T cells to the T cell zone, and CCR7 is a marker of cTR cells (40). Dll4 neutralization decreased the cTR cell populations (Fig 3G), while eTR cells were not altered in mLN (Fig 3H). These data suggested that Dll4 specifically sustained cTR cells in draining lymph node during RSV infection.

Figure 3. Dll4 inhibition impairs the maintenance of central Treg cells in lymph node in vivo.

A. Percentage of Foxp3+ Treg in mLN at 6 dpi

B. Representative flow cytometric analysis showing Foxp3 expression in CD62LhiCD44lo central CD4 T cells in mLN at 6 dpi

C. Percentage of Foxp3+ cells in CD62LhiCD44lo central CD4 T cells harvested from the mLN at 6 dpi

D. Mean fluorescence intensity of Foxp3 in CD62LhiCD44lo central CD4 T cells in mLN at 6 dpi

E. Representative flow cytometric analysis showing CCR7 expression in CD62LhiCD44lo central CD4 T cells in mLN at 6 dpi

F. Mean fluorescence intensity of CCR7 in CD62LhiCD44lo central CD4 T cells in mLN at 6 dpi

G. Percentage of CD62LhiCD44loFoxp3+ central Treg in mLN at 6 dpi

H. Percentage of CD44hiCD62LloFoxp3+ effector Treg in mLN at 6 dpi

Data represent mean ± s.e.m. Each symbol represents individual mouse processed and analyzed separately. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments * P<0.05; ** P<0.005; *** P<0.0005; NS: no significance (unpaired two-tailed t-test)

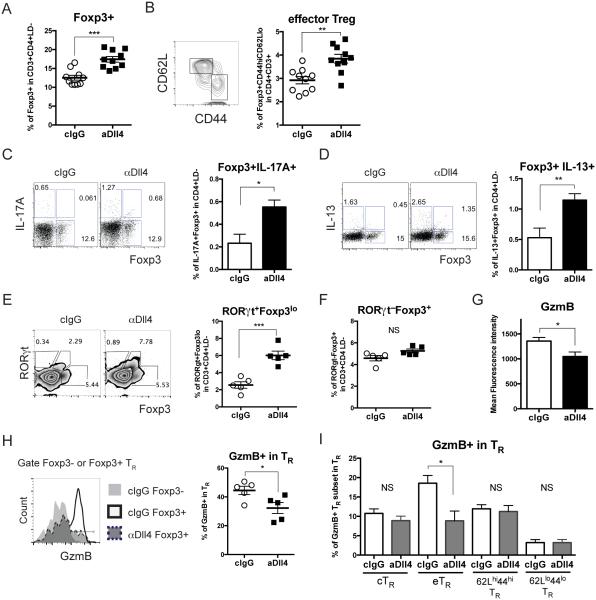

In contrast its effects in lymph nodes, Dll4 neutralization enhanced the abundance of Foxp3+ Treg cells in the lungs of infected mice (Fig 4A) and CD44hi CD62Llo Foxp3+ eTR cells in lung at 8 dpi (Fig 4B) without affecting cTR cells (data not shown). Based on our previous finding that Dll4 blockade enhanced IL-13 and IL-17A production in CD4 T cells (Fig 2I), we examined if Dll4 can also perturb cytokine production in Foxp3+ CD4 T cells. Lung cells harvested at 8 dpi were re-stimulated and stained for intracellular Foxp3, IL-13 and IL-17A before flow cytometric analysis. In vivo Dll4 blockade significantly increased the abundance of IL-17A+Foxp3+ (Fig 4C) and IL-13+Foxp3+ (Fig 4D) but not IL-13−, IL-17A−, Foxp3+ Treg cells (data not shown). To further characterize if Dll4 regulates either Th17 or Th2 transcription factor co-expression in Treg cells, RORγt or GATA3 were co-stained with Foxp3 after re-stimulation. Dll4 neutralization increased the percentage of RORγt+Foxp3lo cells and RORγt+Foxp3− but not RORγt−Foxp3+ after 8 dpi (Fig 4E, F). We did not detect significant changes in either GATA3+ Treg cells or total GATA3+ CD4 T cells in both lung and LN after Dll4 inhibition (data not shown). These data suggested that Dll4 inhibition drove a Th17-like effector phenotype in Treg cells during RSV infection in vivo.

Figure 4. Dll4 blockade drives effector-like, inflammatory, and less functional Treg cells in the lungs during RSV infection.

A. Percentage of Foxp3+ Treg in lung were analyzed at 8 dpi

B. Percentage of CD44hiCD62LloFoxp3+ effector Treg in lung at 8 dpi

C. Percentage of IL-17A-producing Treg cells in lung from 8 dpi after PMA and Ionomycin re-stimulation were measured.

D. Percentage of IL-13-producing Treg cells in lung from 8 dpi after PMA and Ionomycin re-stimulation were measured.

E. Percentage of RORγt+Foxp3lo CD4 T cells in lung from 8dpi after PMA and Ionomycin re-stimulation were measured.

F. Percentage of RORγt−Foxp3+ CD4 T cells in lung from 8dpi after PMA and Ionomycin re-stimulation were measured.

G. Mean fluorescence intensity of GzmB in Foxp3+ Treg in the lung at 8 dpi

H. Representative flow cytometry showed the frequency of GzmB+ in Foxp3+ Treg in the lung at 8 dpi

I. Percentage of GzmB+ effector Treg (eTR), central Treg (cTR), CD62LhiCD44hi Treg, and CD62LloCD44lo Treg in the lung after 8 dpi

Data represent mean ± s.e.m. Each symbol represents individual mouse processed and analyzed separately. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. * P<0.05; ** P<0.005; *** P<0.0005; NS: no significance (unpaired two-tailed t-test)

To further investigate if Dll4 regulated Treg cell functional markers, several were examined—Inducible T cells co-stimulator (ICOS), Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), Granzyme B (GzmB), and Neuropilin-1 (Nrp1). Dll4 inhibition decreased the expression of GzmB, while ICOS, PD-1 and Nrp1 expression was unchanged in Foxp3+ Treg cells at 8 dpi (Fig 4G and data not shown). It was previously shown that during RSV infection, GzmB was the critical functional molecule for Treg cell function to limit the associated immunopathology (26). We found that Dll4 neutralization decreased the frequency of GzmB+ in Foxp3+ Treg cells in the lung after 8 dpi (Fig 4H), especially prominently for GzmB+ eTR cells (Fig 4I). Our results indicate that Dll4 prevented Foxp3 Treg cell acquisition of Th17-like effector phenotype, and it supported GzmB expression in Treg cells in the lung during RSV infection.

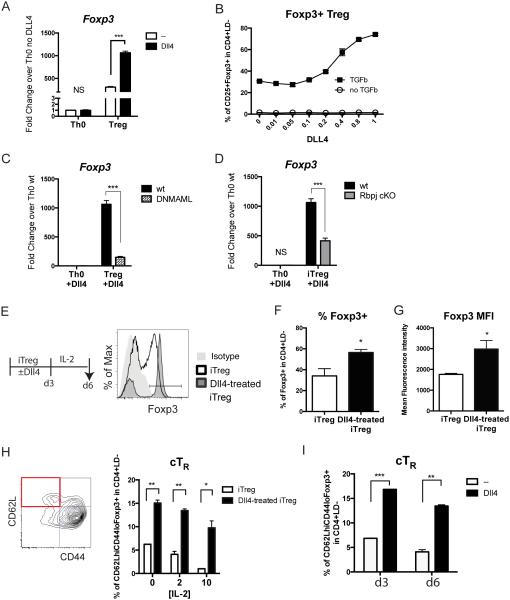

Dll4 activates and maintains inducible Treg cells in vitro

Our data reveal differential effects of Dll4 in Foxp3+ Treg cells in lymphoid vs. non-lymphoid tissue during pulmonary infection. To further investigate Dll4 effects on Treg cell differentiation in a controlled context, splenic CD4+CD25−CD62LhiCD44lo naïve CD4 T cells were activated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 with or without plate-bound recombinant Dll4, and skewed toward Treg cells with TGF-β and IL-2. We first confirmed that Dll4 was able to activate expression of the Notch target gene Hes1 in naïve CD4 T cells, Th0 and Treg cells (Sup Fig 2A,B,C) in a dose-dependent manner (Sup Fig 2C) and activated intracellular domain of Notch1 (N1ICD) cleavage (Sup Fig 2D). Subsequently, naïve T cells were skewed toward Th0 or iTreg cells. Foxp3 expression was significantly increased with Dll4 activation under iTreg cell skewing conditions (Fig 5A). Importantly, Dll4 increased CD25+Foxp3+ iTreg cells in a dose-dependent manner only in the presence of TGF-β (Fig 5B). Furthermore, Foxp3 expression was significantly decreased with homozygous ROSA26-driven expression of the pan-Notch-inhibitor dominant negative Mastermind-like 1 (DNMAML1) (Fig 5C), and with inactivation of the Rbpj gene, encoding RBP-Jκ (Fig 5D). Since MAML1 and RBP-Jκ mediate transcriptional activation from Notch signaling, these data revealed that Dll4-activated Foxp3 expression was dependent upon canonical RBP-Jκ/MAML-dependent Notch signaling. To further characterize Foxp3+ cells in this differentiation system, primary Dll4-activated iTreg cell cultures were rested in IL-2 for 3 days without Dll4 (Fig 5E). Dll4-treated iTreg cells consistently maintained a higher percentage of Foxp3+ (Fig 5F) and higher Foxp3 expression (Fig 5G). To investigate whether Dll4 affected homeostatic features on Treg cells during in vitro skewing, CD62L and CD44 expression was evaluated before or after the IL-2 rest phase. Naïve CD4 T cells that were exposed to Dll4 during primary iTreg cell skewing maintained more CD62LhiCD44loFoxp3+ cells consistently independent of the dose of IL-2 during the rest period (Fig 5H) and at multiple time points after primary skewing (Fig 5I). These data suggest that the presence of Dll4 during iTreg cell activation and differentiation stabilized Foxp3 expression and sustained more Treg cells with CD62LhiCD44lo phenotype in vitro.

Figure 5. Dll4 promotes Foxp3 expression and sustains central Treg cells during iTreg differentiation.

A. Inducible Treg (iTreg) and activated T cells (Th0) were skewed from naïve CD4 T cells for 48 hours with or without plate-bound Dll4 in vitro. Foxp3 expression were measured.

B. CD25+Foxp3+ iTreg were skewed from naïve CD4 T cells for 72 hours with or without 2 ng/mL of TGF-β and indicated concentration of Dll4 (μg/mL)

C. Foxp3 expression after 48 hours skewing from either wild type naïve CD4 T cells or naive T cells expressing dominant negative MAML1 (DNMAML)

D. Foxp3 expression after 48 hours skewing from either wild type or CD4-specific Rbpj-deficient naïve CD4 T cells

E. Naïve CD4 T cells from wild type B6 mice were skewed toward iTreg with or without Dll4 stimulation for 72 hours (d3), then rested in 10 ng/mL of IL-2 for another 72 hours. Representative flow cytometry showed the expression of Foxp3 in viable CD4 T cells at day 6 (d6).

F. Percentage of Foxp3+ in viable CD4 T cells at day 6.

G. Mean fluorescence intensity of Foxp3 in viable Foxp3+ CD4 T cells at day 6

H. Percentage of CD62LhiCD44loFoxp3+ central Treg (cTR) after 0 ng/mL, 2 ng/mL and 10 ng/mL of IL-2 resting at day 6 iTreg culture

I. Percentage of cTR at day 3 and day 6 with 2 ng/mL of IL-2 in iTreg culture

Data represent mean ± s.e.m. Each symbol represents individual mouse processed and analyzed separately. Data are representative of at least two experiments * P<0.05; ** P<0.005; *** P<0.0005; NS: no significance (unpaired two-tailed t-test)

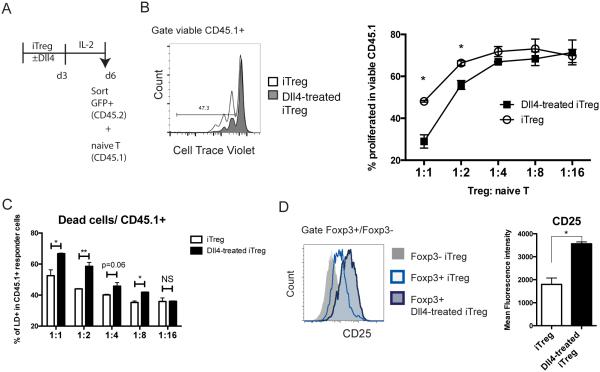

Dll4-exposed iTreg are more suppressive in vitro

Our data showed that Dll4 inhibition decreased Treg cell functional markers during RSV infection (Fig 4), and Dll4/Notch directly sustained Foxp3 expression and cTR cells (Fig 5). These findings imply that Dll4 may change Treg cell function. To further evaluate the function of iTreg cells after Dll4 exposure, we sorted viable, Foxp3-eGFP+ iTreg cells from iTreg cultures on day 6 and co-cultured these cells with CD45.1+ naïve CD4 T cells as responders. CD45.1+ naïve T cells were labeled with CellTrace Violet (CTV) and stimulated with α-CD3/α-CD28 mouse T activator for 72 hours. Viable CD45.1+ cells were gated to examine CTV dilution as readout of cell proliferation (Fig 6A). Responder cells that were co-cultured with Dll4-treated iTreg cells were less proliferative, especially at the 1:1 and 1:2 cell ratio of Treg: Tnaive (Fig 6B), suggesting that Dll4-treated iTreg cells were more suppressive than iTreg cells without Dll4. Intriguingly, CD45.1+ responder cells were less viable when co-culture with Dll4-exposed iTreg cells (Fig 6C). Because one of the functions of Treg cells is to consume survival signals from other T cells, we evaluated IL-2Rα (CD25) expression after 6 days of iTreg cell skewing. Co-stimulation of iTreg cells with Dll4 enhanced CD25 expression on Foxp3+ Treg in vitro (Fig 6D). There data indicated that Dll4-exposed iTreg were more functional in vitro.

Figure 6. Dll4-exposed iTreg are more suppressive in vitro.

A. Schematic representation of the in vitro suppression assay. Naïve CD4 T cells from Foxp3-eGFP knock-in mice underwent iTreg differentiation with or without Dll4 for 72 hours, and resting in 2 ng/mL IL-2 for 72 hours. Viable iTreg or Dll4-exposed iTreg were sorted out as Foxp3-eGFP+ DAPI−, and co-cultured with CellTrace violet (CTV) labeled CD45.1+ naïve T cells with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 beads.

B. After 3 days in co-culture, proliferation was assessed by CTV dilution in CD45.1+ responder cells.

C. After 3 days co-culture, viability was characterized by Live/Dead staining (LD) in CD45.1 responder cells

D. CD25 expression by viable iTreg at day 6

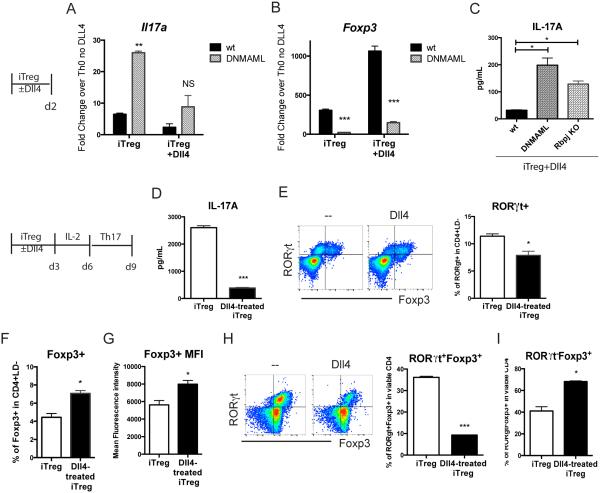

Dll4 and Notch activation strengthened iTreg to be less plastic toward Th17

Data above showed that Dll4 inhibition increased Th17-like Treg cells during RSV infection. To examine whether Dll4 and Notch signaling could inhibit acquisition of a Th17 effector phenotype in iTreg cells, naïve CD4 T cells were purified and cultured in iTreg skewing conditions. Il17a expression was examined during iTreg cell skewing. Inactivation of Notch increased Il17a expression during iTreg cell skewing (Fig 7A), while Foxp3 transcripts were decreased (Fig 7B). Both DNMAML1 expression and Rbpj inactivation in CD4 T cells led to increased IL-17A in iTreg+ Dll4 skewed cultures (Fig 7C). These data suggest that intrinsic Notch activation inhibited Il17a expression while enhancing Foxp3 expression in iTreg cells during differentiation. To further investigate whether Dll4 affects IL-17A production after Treg cell differentiation, an equal number of cells were challenged under IL-6 + TGFβ Th17 conditions for 3 more days after the standard 6 day iTreg cell skewing culture. In Th17 re-stimulation, Dll4-treated iTreg cells secreted significantly less IL-17A (Fig 7D) with associated decreased RORγt+ cells (Fig 7E). Furthermore, Dll4-exposed iTreg cells retained a higher percentage and expression level of Foxp3 (Fig 7F, 7G). These data suggest that Dll4-mediated signals during iTreg cell differentiation led to less inflammatory Th17 skewing while maintaining Treg cell commitment. To clarify if Dll4-educated Foxp3+ iTreg cells had less plasticity to become RORγt+, 105 viable Foxp3-eGFP+ iTreg cells were sorted after 6 days of skewing and cultured in Th17 conditions. Approximately 40% of eGFP+ iTreg cells without Dll4 acquired RORγt+ expression, whereas Dll4-skewed eGFP+ iTreg cells expressed significantly less and RORγt+Foxp3+ (Fig 7H). While a similar amount of eGFP+ cells lost their Foxp3 expression to be Foxp3− in either non-Dll4 or Dll4-educated iTreg cells (data not shown), Dll4-treated iTreg cells still retained more Foxp3+RORγt− during Th17 skewing (Fig 7I). These data suggest that Dll4-educated iTreg cells had less plasticity in an inflammatory Th17 environment.

Figure 7. Dll4/Notch activated iTreg cells retain Foxp3 expression and are resistant to Th17 skewing in vitro.

A. Splenic naïve CD4 T cells from DNMAML or wild type (wt) B6 mice were skewed toward iTreg for 48 hours. Il17a expression in iTreg culture were measured.

B. Foxp3 expression in iTreg culture were measured by realtime PCR after 48 hours of skewing.

C. IL-17A secretion from iTreg were measured by luminax system after 48 hours of skewing

D. Naïve CD4 T cells from wild type B6 mice were skewed toward iTreg with or without Dll4 stimulation for 72 hours, then rested in 10 ng/mL of IL-2 for another 72 hours. At day 6, 5 × 105 of viable cells were re-stimulated in Th17 conditions. After 3 days, IL-17A in the supernatant was accessed

E. Percentage of RORγt+ in viable CD4 T cells after Th17 skewing

F. Percentage of Foxp3+ in viable iTreg or Dll4-exposed iTreg after Th17 skewing

G. Expression level of Foxp3 in viable Foxp3+CD4 T cells in iTreg or Dll4-exposed iTreg culture after Th17 skewing

H. Naïve CD4 T cells from wild type B6 mice were skewed toward iTreg with or without Dll4 stimulation for 72 hours, then rested in 10 ng/mL of IL-2 for another 72 hours. 5 × 105 of viable Foxp3-eGFP+ cells were sorted out and re-stimulated in Th17 conditions at day 6. After 3 days, the percentage of RORγt+Foxp3+ was determined

I. Percentage of RORγt−Foxp3+ after Th17 re-stimulation on Foxp3-eGFP+ cells

DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to determine if the Notch ligand Delta-like 4 (Dll4) influenced Foxp3+ Treg cell development, homeostasis, and function during pulmonary infection. Notch signaling has been suggested to be instrumental in Foxp3+ Treg cell formation and maintenance (18, 41). Notch ligands—Dll1, Jagged1 and Jagged2—have been shown to regulate Treg cell expansion and elicit suppressive activity (14, 17, 42). The present study suggests that Dll4 mechanistically regulates the stability of iTreg cells. Previous studies showed that primary RSV infection enhanced Foxp3+ Treg cells in the airway (25, 38). Our data indicate that Dll4 sustained Foxp3 expression especially in central Treg cells, and altered homeostatic features and functional markers of Treg cells. In vivo Dll4 inhibition allowed the acquisition of effector cytokine production in Treg cells, increased their effector phenotype (CD44hiCD62Llo), and decreased functional Treg cell markers (GzmB) during infection. In vitro skewing of iTreg cells costimulated with Dll4 from naïve T cells had enhanced regulatory function, retained their central Treg cell phenotype, and were more stable with less susceptibility to become RORγt+ Th17 cells. Importantly, stable and functional Treg cells prevent autoimmunity and enhance immunity against chronic infection (43). Thus, identifying Dll4 as one stabilizing factor in autologous Treg cells could potentially further optimize clinical efficacy of treatment protocols (44, 45).

Dll4/Notch signaling appears to have differential functions in various disease models. Using systemic blockade, Dll4 inhibition ameliorated graft-versus-host disease, Type 1 diabetes, and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (20, 22, 46–48). In contrast, Dll4 blockade leads to exacerbated allergic airway disease and pulmonary RSV infection responses, as well as to increased BCG-induced granuloma formation (9, 49). These different results could be reconciled with a revised model that Notch signaling fine-tunes T cell responses to different environmental cues (5), and thereby plays a distinct role in different diseases, such as antigen driven/infectious vs. autoimmune or allogeneic responses. Recently, a novel study demonstrated that intrinsic Notch signaling limited peripheral Treg cell maintenance during steady state and in Graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) (18). In contrast to these latter finding, our results suggests that Dll4 and canonical Notch signaling sustained iTreg cell differentiation and stability to prevent immunopathogenesis of pulmonary infection. Recent evidence supports that iTreg cells are important for mucosal homeostasis, suppression of immune responses to environmental and food antigens, and to impede mucosal inflammation. In contrast, natural occurring Treg (nTreg) cells prevent autoimmunity and alter the threshold of immune activation (50, 51). Notch signaling and Dll4 restrain nTreg development in vivo (20), and GvHD was mainly prevented by nTreg (52, 53) but not iTreg due to lineage instability (54). To answer the question if Dll4 differentially affects nTreg versus iTreg cells, we used Neuropilin-1 (Nrp1) to distinguish nTreg versus iTreg cells in vivo as described (55–58). Our preliminary findings showed that Dll4 inhibition decreased Nrp1− Treg cells during RSV infection but not Nrp1+ Treg cells in the spleen (data not shown). Therefore, we speculate that Dll4/Notch may have a differential role on nTreg versus iTreg, thereby limiting nTreg cells in GvHD but enhance iTreg cells in RSV infection. Additional research needs to be done to elucidate this intriguing hypothesis.

RSV infection can induce IL-17A production (37, 59) and IL-17A facilitates mucus production to promote Th2-driven immunopathology (37). Furthermore, Treg cells could be reprogrammed to Th17-like in the presence of appropriate inflammatory cytokines (60). iTreg cell plasticity is critical for conversion to IL-17A-producing Foxp3+ and RORγt+Foxp3+ populations under multiple microenvironments and diseases (62–64). In this current study, Dll4 prevented IL-17A+ Treg cell development in infected mice. Moreover, Dll4-"educated" Foxp3-GFP+ iTreg cells retained higher Foxp3 expression and resisted skewing toward Th17 in vitro. These results indicate that Dll4 modulates Treg cell stability and plasticity toward Th17 in inflammatory environments.

Pathogenic RSV infection also exhibits a type 2 biased immune response (65). Our group has shown that Dll4 prevented Th2 cytokine secretion in CD4 T cells during RSV infection. Since both Notch signaling and Treg cells have been reported to be involve in Th2 programs, it raised a question if Dll4 regulates Th2 cytokine production directly or indirectly through Treg cell effects. Surprisingly, our data did not demonstrate a significant perturbation in GATA3+ Th2 lineage after Dll4 inhibition (data not shown). Instead, our data presented a dysfunctional Treg cell and Th17-like effector phenotype after Dll4 inhibition. Since IL-17A can enhance Th2 responses in RSV infection and other pulmonary inflammation, these results may suggest that the Th2 response is a result of an indirect effect of reduced Treg cell function and increased IL-17.

Beside Th2 cells, recent studies have demonstrated that RSV infection enhances type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) with a concurrent IL-13 increase (34). The present study indicated that Dll4 inhibition increased the number of ILC2 corresponding with elevated IL-5 and IL-13 levels. Notch activation has been shown to support ILC2 progenitor development in vitro (41, 66), but the in vivo role of Dll4 in ILC2 biology during infection has not been described. Our novel findings further highlight the importance of Dll4 in ILC2 homeostasis in vivo, but it is not clear whether the regulation is direct or indirect. Since iTreg cells inhibit ILC2 and attenuate pulmonary inflammation (67), future studies will be necessary to specify the indirect contribution of iTreg cells in restraining ILC2 during pulmonary infection.

The homeostatic features of Foxp3+ Treg cells were characterized with CD62L, CD44, and CCR7. CD62LhiCD44loCCR7+ cTR cells are quiescent, long-lived, and dependent on IL-2, whereas CD44hiCD62LloFoxp3+ eTR appear to be shorter lived (40, 68). These two subpopulations favored distinct compartments, as cTR cells homing to secondary lymphoid organs (SLO) to be suppressive for autoimmunity (69). Lymph node sensitization is critical to mount a proper immune response since insufficient lymph node formation led to impaired Foxp3 Treg cell function, promoted IL-17A-mediated pulmonary pathology, and initiated lymphoid cell clusters in the lung (70, 71). In the present study, data showed that Dll4 sustained the cTR cell population in SLO while preventing Th17 effector phenotype during RSV infection, representing a novel role of Dll4 in cTR cell maintenance.

In addition to the alteration of the Treg cell cytokine phenotype, the present study further suggests that Dll4 sustained Treg cell function by influencing GzmB in vivo and CD25 in vitro. Intriguingly, GzmB in Foxp3+ Treg cells controlled RSV-induced T cells infiltration in airways (26), and GzmB has been postulated to be a better functional marker of iTreg cells during viral infection (72). Further investigation on the function of Treg subsets during RSV infection needs to be characterized in the future. Here, our finding in GzmB may provide a mechanistic explanation for Dll4 inhibition in exacerbating RSV-induced CD4 and CD8 T cells infiltration (9).

Taken together, our study demonstrates that Dll4/Notch promotes iTreg cell development, homeostasis, stability/plasticity, and function in vitro and in vivo during RSV infection. Dll4 prevented RSV pathogenesis and supported iTreg cell development in vitro. The effects of Dll4 on Treg cells are an example of how Notch signaling can promote T cell homeostasis and disease regulation. By extending our understanding of Dll4 in Treg cell stability and function, our results may provide a road for future translational research leading to a better therapeutic strategy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Matthew Schaller, Denise de Almeida Nagata, Catherine Ptaschinski, and Ivan Maillard for helpful discussions.

Funding for the research was provided in part by NIH Grants AI036302 (NWL) and AI091627 (IPM).

REFERENCE

- 1.Hozumi K, Mailhos C, Negishi N, Hirano K, Yahata T, Ando K, Zuklys S, Holländer GA, Shima DT, Habu S. Delta-like 4 is indispensable in thymic environment specific for T cell development. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:2507–2513. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amsen D, Blander JM, Lee GR, Tanigaki K, Honjo T, Flavell RA. Instruction of distinct CD4 T helper cell fates by different notch ligands on antigen-presenting cells. Cell. 2004;117:515–526. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00451-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laky K, Evans S, Perez-Diez A, Fowlkes BJ. Notch signaling regulates antigen sensitivity of naive CD4+ T cells by tuning co-stimulation. Immunity. 2015;42:80–94. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amsen D, Blander JM, Lee GR, Tanigaki K, Honjo T, Flavell RA. Instruction of distinct CD4 T helper cell fates by different notch ligands on antigen-presenting cells. Cell. 2004;117:515–526. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00451-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailis W, Yashiro-Ohtani Y, Fang TC, Hatton RD, Weaver CT, Artis D, Pear WS. Notch simultaneously orchestrates multiple helper T cell programs independently of cytokine signals. Immunity. 2013;39:148–159. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minter LM, Turley DM, Das P, Shin HM, Joshi I, Lawlor RG, Cho OH, Palaga T, Gottipati S, Telfer JC, Kostura L, Fauq AH, Simpson K, Such KA, Miele L, Golde TE, Miller SD, Osborne BA. Inhibitors of gamma-secretase block in vivo and in vitro T helper type 1 polarization by preventing Notch upregulation of Tbx21. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:680–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amsen D, Antov A, Jankovic D, Sher A, Radtke F, Souabni A, Busslinger M, McCright B, Gridley T, Flavell RA. Direct regulation of Gata3 expression determines the T helper differentiation potential of Notch. Immunity. 2007;27:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang TC, Yashiro-Ohtani Y, Del Bianco C, Knoblock DM, Blacklow SC, Pear WS. Notch directly regulates Gata3 expression during T helper 2 cell differentiation. Immunity. 2007;27:100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schaller MA, Neupane R, Rudd BD, Kunkel SL, Kallal LE, Lincoln P, Lowe JB, Man Y, Lukacs NW. Notch ligand Delta-like 4 regulates disease pathogenesis during respiratory viral infections by modulating Th2 cytokines. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:2925–2934. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun J, Krawczyk CJ, Pearce EJ. Suppression of Th2 cell development by Notch ligands Delta1 and Delta4. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950. 2008;180:1655–1661. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elyaman W, Bassil R, Bradshaw EM, Orent W, Lahoud Y, Zhu B, Radtke F, Yagita H, Khoury SJ. Notch receptors and Smad3 signaling cooperate in the induction of interleukin-9-producing T cells. Immunity. 2012;36:623–634. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mukherjee S, Schaller MA, Neupane R, Kunkel SL, Lukacs NW. Regulation of T cell activation by Notch ligand, DLL4, promotes IL-17 production and Rorc activation. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950. 2009;182:7381–7388. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barbarulo A, Grazioli P, Campese AF, Bellavia D, Di Mario G, Pelullo M, Ciuffetta A, Colantoni S, Vacca A, Frati L, Gulino A, Felli MP, Screpanti I. Notch3 and canonical NF-kappaB signaling pathways cooperatively regulate Foxp3 transcription. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950. 2011;186:6199–6206. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kared H, Adle-Biassette H, Foïs E, Masson A, Bach J-F, Chatenoud L, Schneider E, Zavala F. Jagged2-expressing hematopoietic progenitors promote regulatory T cell expansion in the periphery through notch signaling. Immunity. 2006;25:823–834. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ou-Yang H-F, Zhang H-W, Wu C-G, Zhang P, Zhang J, Li J-C, Hou L-H, He F, Ti X-Y, Song L-Q, Zhang S-Z, Feng L, Qi H-W, Han H. Notch signaling regulates the FOXP3 promoter through RBP-J- and Hes1-dependent mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2009;320:109–114. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9912-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perumalsamy LR, Marcel N, Kulkarni S, Radtke F, Sarin A. Distinct spatial and molecular features of notch pathway assembly in regulatory T cells. Sci. Signal. 2012;5:ra53. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samon JB, Champhekar A, Minter LM, Telfer JC, Miele L, Fauq A, Das P, Golde TE, Osborne BA. Notch1 and TGFbeta1 cooperatively regulate Foxp3 expression and the maintenance of peripheral regulatory T cells. Blood. 2008;112:1813–1821. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-144980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charbonnier L-M, Wang S, Georgiev P, Sefik E, Chatila TA. Control of peripheral tolerance by regulatory T cell-intrinsic Notch signaling. Nat. Immunol. 2015;16:1162–1173. doi: 10.1038/ni.3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bassil R, Zhu B, Lahoud Y, Riella LV, Yagita H, Elyaman W, Khoury SJ. Notch ligand delta-like 4 blockade alleviates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by promoting regulatory T cell development. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950. 2011;187:2322–2328. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Billiard F, Lobry C, Darrasse-Jèze G, Waite J, Liu X, Mouquet H, DaNave A, Tait M, Idoyaga J, Leboeuf M, Kyratsous CA, Burton J, Kalter J, Klinakis A, Zhang W, Thurston G, Merad M, Steinman RM, Murphy AJ, Yancopoulos GD, Aifantis I, Skokos D. Dll4-Notch signaling in Flt3-independent dendritic cell development and autoimmunity in mice. J. Exp. Med. 2012;209:1011–1028. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandy AR, Chung J, Toubai T, Shan GT, Tran IT, Friedman A, Blackwell TS, Reddy P, King PD, Maillard I. T cell-specific notch inhibition blocks graft-versus-host disease by inducing a hyporesponsive program in alloreactive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950. 2013;190:5818–5828. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tran IT, Sandy AR, Carulli AJ, Ebens C, Chung J, Shan GT, Radojcic V, Friedman A, Gridley T, Shelton A, Reddy P, Samuelson LC, Yan M, Siebel CW, Maillard I. Blockade of individual Notch ligands and receptors controls graft-versus-host disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:1590–1604. doi: 10.1172/JCI65477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rudd BD, Schaller MA, Smit JJ, Kunkel SL, Neupane R, Kelley L, Berlin AA, Lukacs NW. MyD88-mediated instructive signals in dendritic cells regulate pulmonary immune responses during respiratory virus infection. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950. 2007;178:5820–5827. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Durant LR, Makris S, Voorburg CM, Loebbermann J, Johansson C, Openshaw PJM. Regulatory T cells prevent Th2 immune responses and pulmonary eosinophilia during respiratory syncytial virus infection in mice. J. Virol. 2013;87:10946–10954. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01295-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fulton RB, Meyerholz DK, Varga SM. Foxp3+ CD4 regulatory T cells limit pulmonary immunopathology by modulating the CD8 T cell response during respiratory syncytial virus infection. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950. 2010;185:2382–2392. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loebbermann J, Thornton H, Durant L, Sparwasser T, Webster KE, Sprent J, Culley FJ, Johansson C, Openshaw PJ. Regulatory T cells expressing granzyme B play a critical role in controlling lung inflammation during acute viral infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2012;5:161–172. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tu L, Fang TC, Artis D, Shestova O, Pross SE, Maillard I, Pear WS. Notch signaling is an important regulator of type 2 immunity. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:1037–1042. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maillard I, Weng AP, Carpenter AC, Rodriguez CG, Sai H, Xu L, Allman D, Aster JC, Pear WS. Mastermind critically regulates Notch-mediated lymphoid cell fate decisions. Blood. 2004;104:1696–1702. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandy AR, Stoolman J, Malott K, Pongtornpipat P, Segal BM, Maillard I. Notch Signaling Regulates T Cell Accumulation and Function in the Central Nervous System during Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 2013;191:1606–1613. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lukacs NW, Moore ML, Rudd BD, Berlin AA, Collins RD, Olson SJ, Ho SB, Peebles RS. Differential immune responses and pulmonary pathophysiology are induced by two different strains of respiratory syncytial virus. Am. J. Pathol. 2006;169:977–986. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amsen D, Blander JM, Lee GR, Tanigaki K, Honjo T, Flavell RA. Instruction of distinct CD4 T helper cell fates by different notch ligands on antigen-presenting cells. Cell. 2004;117:515–526. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00451-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller AL, Bowlin TL, Lukacs NW. Respiratory syncytial virus-induced chemokine production: linking viral replication to chemokine production in vitro and in vivo. J. Infect. Dis. 2004;189:1419–1430. doi: 10.1086/382958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collison LW, Vignali DAA. In vitro Treg suppression assays. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton NJ. 2011;707:21–37. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61737-979-6_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stier MT, Bloodworth MH, Toki S, Newcomb DC, Goleniewska K, Boyd KL, Quitalig M, Hotard AL, Moore ML, Hartert TV, Zhou B, McKenzie AN, Peebles RS. Respiratory syncytial virus infection activates IL-13-producing group 2 innate lymphoid cells through thymic stromal lymphopoietin. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016;138:814–824. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.01.050. e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lukacs NW, Moore ML, Rudd BD, Berlin AA, Collins RD, Olson SJ, Ho SB, Peebles RS. Differential immune responses and pulmonary pathophysiology are induced by two different strains of respiratory syncytial virus. Am. J. Pathol. 2006;169:977–986. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plotnicky-Gilquin H, Cyblat-Chanal D, Aubry J-P, Champion T, Beck A, Nguyen T, Bonnefoy J-Y, Corvaïa N. Gamma interferon-dependent protection of the mouse upper respiratory tract following parenteral immunization with a respiratory syncytial virus G protein fragment. J. Virol. 2002;76:10203–10210. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.20.10203-10210.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mukherjee S, Lindell DM, Berlin AA, Morris SB, Shanley TP, Hershenson MB, Lukacs NW. IL-17-induced pulmonary pathogenesis during respiratory viral infection and exacerbation of allergic disease. Am. J. Pathol. 2011;179:248–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee DCP, Harker JAE, Tregoning JS, Atabani SF, Johansson C, Schwarze J, Openshaw PJM. CD25+ natural regulatory T cells are critical in limiting innate and adaptive immunity and resolving disease following respiratory syncytial virus infection. J. Virol. 2010;84:8790–8798. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00796-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krishnamoorthy N, Khare A, Oriss TB, Raundhal M, Morse C, Yarlagadda M, Wenzel SE, Moore ML, Peebles RS, Ray A, Ray P. Early infection with respiratory syncytial virus impairs regulatory T cell function and increases susceptibility to allergic asthma. Nat. Med. 2012;18:1525–1530. doi: 10.1038/nm.2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smigiel KS, Richards E, Srivastava S, Thomas KR, Dudda JC, Klonowski KD, Campbell DJ. CCR7 provides localized access to IL-2 and defines homeostatically distinct regulatory T cell subsets. J. Exp. Med. 2014;211:121–136. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Radtke F, MacDonald HR, Tacchini-Cottier F. Regulation of innate and adaptive immunity by Notch. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013;13:427–437. doi: 10.1038/nri3445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mota C, Nunes-Silva V, Pires AR, Matoso P, Victorino RMM, Sousa AE, Caramalho I. Delta-like 1-mediated Notch signaling enhances the in vitro conversion of human memory CD4 T cells into FOXP3-expressing regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950. 2014;193:5854–5862. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Workman CJ, Szymczak-Workman AL, Collison LW, Pillai MR, Vignali DAA. The development and function of regulatory T cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS. 2009;66:2603–2622. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0026-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haque R, Lei F, Xiong X, Bian Y, Zhao B, Wu Y, Song J. Programming of regulatory T cells from pluripotent stem cells and prevention of autoimmunity. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950. 2012;189:1228–1236. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sakaguchi S, Vignali DAA, Rudensky AY, Niec RE, Waldmann H. The plasticity and stability of regulatory T cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013;13:461–467. doi: 10.1038/nri3464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bassil R, Zhu B, Lahoud Y, Riella LV, Yagita H, Elyaman W, Khoury SJ. Notch ligand delta-like 4 blockade alleviates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by promoting regulatory T cell development. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950. 2011;187:2322–2328. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mochizuki K, Xie F, He S, Tong Q, Liu Y, Mochizuki I, Guo Y, Kato K, Yagita H, Mineishi S, Zhang Y. Delta-like ligand 4 identifies a previously uncharacterized population of inflammatory dendritic cells that plays important roles in eliciting allogeneic T cell responses in mice. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950. 2013;190:3772–3782. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reynolds ND, Lukacs NW, Long N, Karpus WJ. Delta-like ligand 4 regulates central nervous system T cell accumulation during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950. 2011;187:2803–2813. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jang S, Schaller M, Berlin AA, Lukacs NW. Notch ligand delta-like 4 regulates development and pathogenesis of allergic airway responses by modulating IL-2 production and Th2 immunity. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950. 2010;185:5835–5844. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Curotto de Lafaille MA, Lafaille JJ. Natural and adaptive foxp3+ regulatory T cells: more of the same or a division of labor? Immunity. 2009;30:626–635. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Josefowicz SZ, Niec RE, Kim HY, Treuting P, Chinen T, Zheng Y, Umetsu DT, Rudensky AY. Extrathymically generated regulatory T cells control mucosal TH2 inflammation. Nature. 2012;482:395–399. doi: 10.1038/nature10772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pierini A, Colonna L, Alvarez M, Schneidawind D, Nishikii H, Baker J, Pan Y, Florek M, Kim B-S, Negrin RS. Donor Requirements for Regulatory T Cell Suppression of Murine Graft-versus-Host Disease. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950. 2015;195:347–355. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoffmann P, Ermann J, Edinger M, Fathman CG, Strober S. Donor-type CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells suppress lethal acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196:389–399. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beres A, Komorowski R, Mihara M, Drobyski WR. Instability of Foxp3 expression limits the ability of induced regulatory T cells to mitigate graft versus host disease. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2011;17:3969–3983. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feuerer M, Hill JA, Kretschmer K, von Boehmer H, Mathis D, Benoist C. Genomic definition of multiple ex vivo regulatory T cell subphenotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:5919–5924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002006107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thornton AM, Korty PE, Tran DQ, Wohlfert EA, Murray PE, Belkaid Y, Shevach EM. Expression of Helios, an Ikaros transcription factor family member, differentiates thymic-derived from peripherally induced Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950. 2010;184:3433–3441. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weiss JM, Bilate AM, Gobert M, Ding Y, Curotto de Lafaille MA, Parkhurst CN, Xiong H, Dolpady J, Frey AB, Ruocco MG, Yang Y, Floess S, Huehn J, Oh S, Li MO, Niec RE, Rudensky AY, Dustin ML, Littman DR, Lafaille JJ. Neuropilin 1 is expressed on thymus-derived natural regulatory T cells, but not mucosa-generated induced Foxp3+ T reg cells. J. Exp. Med. 2012;209:1723–1742. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120914. S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yadav M, Louvet C, Davini D, Gardner JM, Martinez-Llordella M, Bailey-Bucktrout S, Anthony BA, Sverdrup FM, Head R, Kuster DJ, Ruminski P, Weiss D, Von Schack D, Bluestone JA. Neuropilin-1 distinguishes natural and inducible regulatory T cells among regulatory T cell subsets in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 2012;209:1713–1722. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120822. S1-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hashimoto K, Durbin JE, Zhou W, Collins RD, Ho SB, Kolls JK, Dubin PJ, Sheller JR, Goleniewska K, O’Neal JF, Olson SJ, Mitchell D, Graham BS, Peebles RS. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in the absence of STAT 1 results in airway dysfunction, airway mucus, and augmented IL-17 levels. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2005;116:550–557. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou L, Lopes JE, Chong MMW, Ivanov II, Min R, Victora GD, Shen Y, Du J, Rubtsov YP, Rudensky AY, Ziegler SF, Littman DR. TGF-beta-induced Foxp3 inhibits T(H)17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORgammat function. Nature. 2008;453:236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature06878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu L, Kitani A, Fuss I, Strober W. Cutting edge: regulatory T cells induce CD4+CD25-Foxp3-T cells or are self-induced to become Th17 cells in the absence of exogenous TGF-beta. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950. 2007;178:6725–6729. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sharma MD, Hou D-Y, Liu Y, Koni PA, Metz R, Chandler P, Mellor AL, He Y, Munn DH. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase controls conversion of Foxp3+ Tregs to TH17-like cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes. Blood. 2009;113:6102–6111. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Loebbermann J, Durant L, Thornton H, Johansson C, Openshaw PJ. Defective immunoregulation in RSV vaccine-augmented viral lung disease restored by selective chemoattraction of regulatory T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:2987–2992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217580110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zeng R, Zhang H, Hai Y, Cui Y, Wei L, Li N, Liu J, Li C, Liu Y. Interleukin-27 inhibits vaccine-enhanced pulmonary disease following respiratory syncytial virus infection by regulating cellular memory responses. J. Virol. 2012;86:4505–4517. doi: 10.1128/JVI.07091-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.O’Donnell DR, Openshaw PJ. Anaphylactic sensitization to aeroantigen during respiratory virus infection. Clin. Exp. Allergy J. Br. Soc. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1998;28:1501–1508. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1998.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wong SH, Walker JA, Jolin HE, Drynan LF, Hams E, Camelo A, Barlow JL, Neill DR, Panova V, Koch U, Radtke F, Hardman CS, Hwang YY, Fallon PG, McKenzie ANJ. Rorα is essential for nuocyte development. Nat. Immunol. 2012;13:229–236. doi: 10.1038/ni.2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rigas D, Lewis G, Aron JL, Wang B, Banie H, Sankaranarayanan I, Galle-Treger L, Maazi H, Lo R, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH, Soroosh P, Akbari O. Type 2 innate lymphoid cell suppression by regulatory Tcells attenuates airway hyperreactivity and requires inducible T-cell costimulator-inducible T-cell costimulator ligand. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Campbell DJ. Control of Regulatory T Cell Migration, Function, and Homeostasis. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950. 2015;195:2507–2513. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ermann J, Hoffmann P, Edinger M, Dutt S, Blankenberg FG, Higgins JP, Negrin RS, Fathman CG, Strober S. Only the CD62L+ subpopulation of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells protects from lethal acute GVHD. Blood. 2005;105:2220–2226. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kallal LE, Hartigan AJ, Hogaboam CM, Schaller MA, Lukacs NW. Inefficient lymph node sensitization during respiratory viral infection promotes IL-17-mediated lung pathology. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950. 2010;185:4137–4147. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kocks JR, Davalos-Misslitz ACM, Hintzen G, Ohl L, Förster R. Regulatory T cells interfere with the development of bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:723–734. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Loffredo-Verde E, Abdel-Aziz I, Albrecht J, El-Guindy N, Yacob M, Solieman A, Protzer U, Busch DH, Layland LE, Prazeres da Costa CU. Schistosome infection aggravates HCV-related liver disease and induces changes in the regulatory T-cell phenotype. Parasite Immunol. 2015;37:97–104. doi: 10.1111/pim.12171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.