Abstract

Grounded on research showing that peer crowds vary in risk behavior, several recent health behavior interventions, including the US Food and Drug Administration’s Fresh Empire campaign, have targeted high-risk peer crowds.

We establish the scientific foundations for using this approach. We introduce peer crowd targeting as a strategy for culturally targeting health behavior interventions to youths. We use social identity and social norms theory to explicate the theoretical underpinnings of this approach. We describe Fresh Empire to demonstrate how peer crowd targeting functions in a campaign and critically evaluate the benefits and limitations of this approach.

By replacing unhealthy behavioral norms with desirable, healthy lifestyles, peer crowd–targeted interventions can create a lasting impact that resonates in the target audience’s culture.

Adolescents and young, or emerging, adults are a priority population for public health interventions, so it is important that these interventions use strategies to maximize their effectiveness. Targeting is one such strategy.1 This approach defines a specific population segment with shared characteristics and uses these characteristics to develop an intervention designed to reach and appeal to that specific segment.2 Although some have advocated lifestyle-3 or psychosocial-based4,5 segmentation, health campaigns more often use sociodemographics to define population subgroups.3,6

For youths, however, peer culture may be a more appropriate referent. Peer crowd targeting7 is an approach in which health education interventions are targeted to youths on the basis of their affiliation with a peer crowd—that is, macrolevel, reputation-based subcultures or collectives with shared preferences, styles, values, and behaviors. Several recent health education interventions, including the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Fresh Empire campaign to prevent tobacco use among multicultural youths,7 have adopted the peer crowd–targeting strategy.

Although there is considerable evidence documenting the extent to which peer crowds vary in health and risk behavior,8 using peer crowds to target public health interventions is still relatively new, and its theoretical and empirical foundations have yet to be reviewed and evaluated. We have drawn on several bodies of literature—primarily social psychology, communication, and marketing or branding—to describe how the concept of peer crowds can be incorporated into public health interventions for youths.

PEER CROWDS AND PEER CROWD TARGETING

Identity exploration and development are central components of adolescence as adolescents emerge into young adulthood9,10; during this time, youths attempt to figure out who they are and how to operate in the world. Because adolescents are confronted with novel situations, adolescence can be bewildering11; it is a time when youths are at heightened susceptibility to risk behavior, and emerging adulthood has been described as “the age of instability.”9 Thus, immediate peers and the broader peer crowd are important resources during these developmental stages.12

Youths identify with broader, more distal, macrolevel subcultures known as peer crowds. Distinct from friendship groups, peer crowds are defined by “a shared set of behaviors, values, norms,” and lifestyles,13(p12) as opposed to by interactions or time spent with others. Therefore, peer crowd identity is “more cognitive than behavioral, more symbolic than concrete and interactional.”14(p365) In other words, identification with a particular crowd is a cognitive phenomenon rather than a purely interactional process in which one spends time with other crowd members. Thus, individuals may identify with a crowd and adopt its norms, even though they have no in-person contact with other crowd members.

Similarly, an individual may follow a certain behavioral pattern associated with a peer crowd (e.g., performing well in school) but not actually cognitively identify with that particular crowd (mainstream). Because peer crowds are determined by crowd members’ shared culture, rather than their interpersonal interaction, peer crowds typically transcend geography and are generally stable over time.8 Thus, it is possible for 2 geographically dispersed individuals to identify with the same crowd and participate in that crowd’s lifestyle. Importantly, peer crowds vary in their propensity to engage in various risk behaviors. Table 1 describes different peer crowds and their associated risk behaviors as commonly found in the literature.15–24

TABLE 1—

Peer Crowds Documented in Peer-Reviewed Literature

| Crowd Names | Crowd Description | Health Behaviors |

| Mainstream, average, regulars; subgroups include academics, brains, nerds, goody–goodies | Does not want to stand out; may excel at school, may be involved in school-related extracurricular activities; obeys parents; dresses in “normal” clothes, does not define self on the basis of a particular music or entertainment preference | Increased likelihood of healthy diet, dieting,15 and weight control behaviors16; decreased likelihood of alcohol use,17 indoor tanning,18 unhealthy eating,15 and smoking cigarettes19 |

| Elite, preppy, popular; subgroups include jocks, athletes, partiers | Values social contact with friends and keeping up with the latest fashion and cultural trends; wears brand name, trendy clothing; spends time with friends, going to parties, going to the mall, playing sports | Increased likelihood of alcohol use,17 indoor tanning,18 exercise, and unhealthy eating15 |

| Hip-hop | Engaged in hip-hop culture; identifies with a sense of struggle in life or having the odds against her or him; identifies strongly with the lyrics of hip-hop music and has an urban clothing style | Increased likelihood of smoking cigarettes and cigarillos20–22 |

| Alternative, counterculture, deviants; subgroups include hipsters, skaters, rockers, goth, emo | Values independence and identifies with a sense of being unique or different from average youths; dresses in distinctly edgy fashions; listens to various genres of rock music, supports local music and art, and spends time going to local rock concerts | Increased likelihood of alcohol use,17 drug use,8 smoking cigarettes,11–14 unhealthy eating, and bulimic behaviors15,16 |

Note. The table summarizes general findings from recent research and is not necessarily a comprehensive list of crowds (e.g., some work has identified a country peer crowd). The measurement of peer crowd and reference group for comparison varies across studies. To account for this, and to acknowledge the fact that peer crowds are determined by shared norms, we organized this table on the basis of crowd descriptions and indicated various names that have been used to label each crowd. Cross and Fletcher44 provide a review of these and related issues for those interested. Sussman et al.8 provide a more thorough overview of peer crowds found in the literature.

Theories of Peer Crowds

Youths’ peer crowd identification affects their behavior through both intrinsic (identity-based) and extrinsic (norms-based) mechanisms. Several theories offer guidance for understanding these mechanisms and, correspondingly, how peer crowds can be used in health communication campaigns. These theories can be distilled down to 2 primary approaches: the social identity approach and the social norms approach. Both approaches postulate that the more strongly individuals identify with a certain crowd, the more likely their behavior will mimic the crowd’s behavioral norm.

The social identity approach25,26 posits that individuals develop a sense of identity from the social crowds and categories to which they belong.26 Identification with a social crowd or category provides individuals with a sense of esteem and belonging and helps them structure and make sense of their social environment26; this is particularly relevant for youths, who use peer crowds to help navigate the complex social world. Social identification with a peer crowd also helps young people structure their behavior. Individuals develop prototypes for different crowds, which are cognitive representations of a crowd’s norms. As young people identify more strongly with a particular peer crowd, they begin to map the crowd’s prototype onto their own identity and subsequently use the prototype to guide their behavior. Thus, young people who identify with peer crowds for which risky behavior is normative will be more likely to engage in those risky behaviors because they are acting in accordance with their social identity.

The social norms approach27 offers a complementary explanation of how peer crowds affect behavior, noting that conformity to a peer crowd’s norm is motivated by extrinsic factors such as social approval and group belonging. Social norms are a “set of expectations concerning the attitudes, beliefs and behavior of a particular group of people.”26(p159) Social norms are context specific28 and are contingent on a corresponding reference group. In other words, in any particular context (e.g., a concert), individuals will look to the relevant reference group (other concert attendees) to inform their behavior. The social landscape of other youths is an important context for young people. The theory of normative social behavior29 posits that the extent to which individuals identify with a particular reference group is an important factor modifying the extent to which they conform to that group’s norms. Specifically, individuals strongly adhere to the norms of groups with which they strongly identify.28 Thus, conforming to the norms of a particular peer crowd can provide a young person with social rewards, such as the approval of crowd members.

Theories of Peer Crowd Targeting

To persuade a population to engage in behavior change, health education interventions must typically prompt a sequence or hierarchy of effects,30 that is, a series of processes ultimately resulting in persuasion. McGuire et al.30 posit that before a campaign can begin to persuade an audience member, it must first accomplish 3 goals. First, the audience must “tune in” to the message: a persuasive health communication message must first reach its intended audience. Second, the audience must attend to the message: even if audience members are present while a message airs, persuasion is unlikely unless they pay attention to the message. Third, the audience must like and maintain interest in the message: message characteristics that promote negative affect (e.g., annoying music, unlikeable characters) can prompt individuals to reject even the most persuasive argument, whereas those that engender positive affect can increase the likelihood of persuasion. Once individuals have sufficiently engaged with the message, they are capable of being persuaded by it (i.e., shifting beliefs, attitudes, and behavior).

The Comello's prism model31 provides a theoretical foundation for how peer crowd–targeted interventions should be expected to produce this hierarchy of effects, hypothesizing that one’s identity moderates the effects of a media message. That is, individuals’ identification with a particular peer crowd acts as a lens—or prism—through which they receive, interpret, and act on a message. Thus, we would expect youths who identify with different peer crowds to vary in their exposure to, attention to, and liking of a targeted peer crowd campaign. For instance, the alternative crowd would be expected to react more favorably to a campaign targeting the alternative crowd and less favorably to a campaign targeting the elite crowd.

Although not exclusively focused on identity, other theories, including the prototype willingness model and social cognitive theory, also offer a way to understand how peer crowd–targeted campaigns operate. The prototype willingness model32 posits that young people form mental typologies, or prototypes, of the typical individual who engages—or does not engage—in a particular risk behavior. These prototypes subsequently inform adolescents’ willingness (or openness) to engage in a risk behavior: the more favorable one’s image of a typical marijuana user, the more willing one would be to use marijuana, for example. Peer crowd–targeted campaigns may alter individuals’ prototypes of those who do not engage in different risk behaviors by aligning abstinence with specific desirable peer crowd identities.

Bandura’s social cognitive theory33 also explicates the role of identification with a character in a persuasive message, positing that identification with the characters modeling a behavior in a persuasive message plays an important role in the persuasiveness of that message. Audiences may identify with characters based on a variety of characteristics (e.g., sociodemographics, personality traits), so targeting health campaigns to specific peer crowds can increase one’s level of identification with the characters in the message.

HEALTH EDUCATION INTERVENTIONS

Developing health education interventions that target young people can present unique challenges—including high levels of reactance34 and susceptibility to peer influence among the audience, as well as a highly competitive media environment—that make it difficult for campaigns to break through the clutter. Peer crowd targeting is a useful approach for addressing these challenges for several reasons (Table 2).

TABLE 2—

How Peer Crowd Targeting Can Help Health Communication Campaigns Affect Adolescent Audiences

| Stage of Persuasion | Challenge With Adolescents | Solution Offered by Peer Crowd Targeting |

| Tuning in | Expansive and diverse media landscape can make it difficult to reach target audience | Peer crowds have distinct media patterns in which messages can be placed, including digital and social media |

| Attending | Adolescents’ heavy daily media diet reduces the likelihood adolescents will pay attention to any 1 message | Peer crowds offer cues (e.g., music, fashions, activities, slang, influencers) that can grab the attention of targeted crowd |

| Liking | Propensity to resist and rebel against persuasive messages decreases likelihood adolescents will like and engage with message | Use of cultural cues can generate liking (including perceived similarity, in-grouping, and trust for campaign or brand) |

| Changing individual-level attitudes, social norms, self-efficacy, and behavior | Peer influence and other predisposing factors in one’s daily life can be more powerful than media messages | Identification with crowd members featured in advertisements can enhance persuasive impact; media is particularly well suited to change social norms; peer crowds offer cues, key beliefs, and values to facilitate tailored behavior change interventions |

| Macrolevel social change | Adolescent culture is heavily dominated by media that often portray unhealthy behaviors; identification with a particular crowd may increase the likelihood adolescents are exposed to unhealthy behaviors via crowd-relevant media | Media play an important role in shaping peer crowd prototypes; public health interventions can function at a macrolevel to change crowd norms |

First, peer crowds offer a way to increase the likelihood that the target population is actually exposed to a message because different crowds have normative preferences for media and entertainment. The relatively consistent media patterns in each peer crowd allow health communicators to strategically target their message in the media most likely to be viewed by individuals who identify with a particular crowd. This increases the likelihood that individuals in a specific crowd will be exposed to the campaign message, while reducing exposure to those outside the peer crowd, thus increasing the efficiency of the campaign.

Next, peer crowds offer a battery of subcultural cues, such as preferred music or favorite celebrities, that can be used to increase the relevance of a campaign and engender liking. Using such subcultural cues allows the campaign to break through the clutter by indicating its relevance to crowd members. Additionally, these cues can help position the campaign as coming from an in-group member, thus increasing the credibility and authenticity of the campaign’s message and decreasing the likelihood the message will be rejected.

Peer crowds also offer cues to better affect attitudes, social norms, and self-efficacy. It is well documented that the more audience members identify with a character in a message, the more likely they are to be persuaded by that message.35 Featuring individuals who are in the same peer crowd as the target audience is 1 way to enhance this identification. Additionally, peer crowds can offer relevant attitudes and values for each crowd, which the campaign could then link to the behavior in question.

Ultimately, targeting through peer crowds opens up the possibility for an intervention to create macrolevel social change. Because an individual’s identification with a peer crowd is grounded more on one’s cognitive identification with a shared culture than on one’s immediate group of friends, health education interventions can work with key cultural influencers, or opinion leaders, to change crowd cultural norms. Additionally, a health education intervention could itself become a key cultural influencer. Many health education campaigns develop brands (e.g., truth and VERB) that represent something meaningful to youths. By successfully targeting a brand to a peer crowd, the brand can act as an opinion leader and set cultural norms, including a new health behavior as the norm. Thus, peer crowd–targeted campaigns have the capacity to change macrolevel crowd cultural norms (or prototypes) in addition to microlevel individual behavior among crowd members.

EVIDENCE FOR PEER CROWD TARGETING

Peer crowd targeting is a logical and theoretically grounded strategy for persuading young people to adopt healthy behaviors, but research testing the effectiveness of this approach is still limited. Although peer crowd targeting has been used in several state-level health promotion efforts, only a few regional studies have evaluated peer crowd–targeted messages. The Commune campaign targeted the hipster crowd (a subgroup of the alternative crowd) among a young adult population in San Diego, working with independent artists from within the peer crowd to create antitobacco artwork featuring tobacco facts that were relevant to their crowd’s values. Postintervention, hipsters showed significantly greater decreases in smoking than did nonhipsters who were sampled.24 A second community-based campaign—HAVOC—targeted the partier crowd (a subgroup of the elite crowd) among young adults in Oklahoma. An evaluation of this campaign found that individuals who recalled being exposed to the HAVOC campaign were less likely to be daily or nondaily cigarette users than were those who did not recall the campaign.21 Additionally, it was found (albeit without statistical significance) that individuals who identified with the partier crowd the HAVOC campaign targeted exhibited slightly greater decreases in smoking behavior than did those who were not partiers.

Some work has also documented the effectiveness of peer crowd targeting using a randomized, controlled experiment. Moran and Sussman7,36 randomized adolescent study participants to view an advertisement targeting the peer crowd with which they most identified or an advertisement targeting a crowd with which they disidentified. Analyses showed that strength of identification with the targeted crowd was associated with increased advertisement-congruent beliefs7 and decreased smoking susceptibility.36

The ecological validity found in the HAVOC and Commune campaign evaluations coupled with the internal validity found in Moran and Sussman’s work provides initial evidence that peer crowd targeting is a promising approach. Further supporting this approach is the long history of subculturally and psychographically targeted campaigns used by commercial marketers, such as tobacco companies.37,38 Future data, such as results from the large-scale evaluation study of the Fresh Empire campaign, will provide further understanding of the utility of this segmentation approach for the delivery of health education messages.

FRESH EMPIRE CAMPAIGN

In 2015, the FDA Center for Tobacco Products launched the Fresh Empire campaign, aimed at reducing tobacco use among at-risk African American, Hispanic, and Asian/Pacific Islander youths in the United States, aged 12 to 17 years, who were influenced by hip-hop culture. The FDA worked with Rescue, a behavior change marketing agency, to develop the campaign. As the first peer crowd–targeted health education campaign with a national scope, Fresh Empire uses a targeting approach that draws from theoretical and research-driven insights on social identity and behavior change theories to more effectively and efficiently achieve the tuning in, attending, and liking stages of persuasion.28,33,39

Rather than attempt to target messaging through demographics alone, the FDA used a peer crowd–targeting approach to develop a campaign that speaks more directly and authentically to the subset of adolescents who are most at risk for tobacco use. The development of this approach began with a review of the literature and an assessment of predominant and at-risk peer crowds and ultimately culminated in the selection of the hip-hop peer crowd as one that both is popular among adolescents and is at a relatively higher risk of tobacco use.20,22,40 Additionally, the tobacco industry’s history of using hip-hop culture in marketing strategies demonstrated both the power of targeted marketing tactics and the need for a tobacco prevention campaign developed specifically for hip-hop youths.37

Fresh Empire was developed on the basis of insights from extensive qualitative and quantitative formative research with adolescents in the hip-hop crowd. This research was designed to inform brand and message design and dissemination and included the testing of brand concepts, strategic and creative concepts, and tobacco facts that informed the creation of salient messages. These messages were designed to reflect the reality of hip-hop adolescents’ lives and values, such as being fashionable, authentic, and creative and working hard to achieve culturally relevant success. The campaign seeks to highlight the disconnect between negative tobacco use consequences and hip-hop values and persuade adolescents that it is in their interest to live a tobacco-free lifestyle.

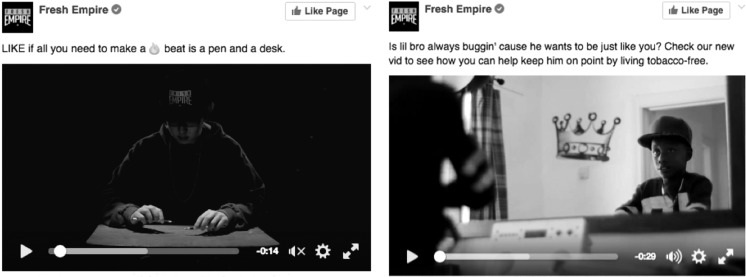

The campaign uses television advertisements aired during programs most popular among the hip-hop peer crowd to maximize reach and frequency to the target audience. In addition, interactive social media and local community engagement experiences play an integral role in the campaign strategy. The Fresh Empire social media presence (Figure 1) interweaves tobacco messages tailored to the beliefs and values of the peer crowd with lifestyle posts about activities, local events, and social norms important to hip-hop youths. This is done to grab the attention of hip-hop adolescents and to establish the brand as a well-liked, authentic, and trusted source of information.

FIGURE 1—

Examples of Fresh Empire Social Media Posts: United States, 2015

Note. More examples of Fresh Empire’s social media materials can be found at the following: Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/FreshEmpire; Twitter: https://twitter.com/freshempire; Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/freshempire.

This approach is supplemented with direct engagement at local hip-hop events, where brand ambassadors representing Fresh Empire provide an opportunity for 1-on-1 engagements. These local events link back to social media activities through social media posts featuring images and content from the events. This integrated approach increases the event’s reach to beyond those physically present at the event and helps attract followers to the brand’s social media accounts. During these interactions, the in-group brand ambassadors can authentically relate tobacco-free lifestyles to hip-hop peer crowd values, thereby enhancing the persuasive impact through identification with fellow peer crowd members. This approach further builds the brand’s presence as a credible source of information within the peer crowd, increasing the likelihood that youths will react positively to campaign messaging.

Fresh Empire launched in the Southeast region of the United States in May 2015 and expanded to 36 markets across the United States in October 2015. An ongoing evaluation study is tracking campaign influence on behavioral intentions to use tobacco among youths in the campaign target audience.

LIMITATIONS AND AREAS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

The theoretical and empirical foundations of peer crowd targeting underscore several important points for research and practice involving peer crowds. First, a youth’s affiliation with a particular crowd should be thought of as a continuous and nonmutually exclusive construct. Discussing peer crowds as discrete, bounded phenomena for which membership is categorical is heuristically useful, but misleading. It is more appropriate to conceptualize youths’ identification with a crowd on a continuum that represents how a young person may identify strongly, moderately, or not at all with a crowd. Correspondingly, youths can identify with multiple peer crowds, and these crowds all have influence over their behavior.22 Moreover, adolescent identity development is a process involving different identity statuses determined by level of identity exploration and commitment10,41; so youths may identify with different crowds over their adolescent and young adult years. It is important to be aware of how these transitions could modify the effects of a peer crowd–targeted campaign. It is also worth noting that identity status in itself is associated with risk behavior, with “identity achieved” individuals (those who have committed to an identity after a phase of exploration) being less likely to be prone to risky behavior.42

Second, not all health behaviors are guided by peer crowd identity. For example, individuals’ diet may be rooted more in their cultural heritage or determined by the food choices they are presented. Relatedly, different crowds may affect different types of behavior.43 Identification with the alternative crowd could affect substance use behavior but have no bearing on physical activity, whereas identification with the preppy crowd has been shown to affect physical activity.15 When using peer crowd identification to target youths, it is important to understand whether peer crowds actually inform the risk behavior and, if so, to identify the crowd most relevant to the behavior at hand. A deeper understanding of a particular peer crowd and the values that motivate that crowd are crucial underpinnings to a successful peer crowd–targeted campaign.

Third, measuring peer crowd identification presents several challenges.44,45 Peer crowd membership is typically assessed using self- or peer report. Both approaches have limitations. When using self-report methods, youths may be hesitant to acknowledge identification with a certain crowd, or there may be geographic differences in crowd names (e.g., “popular” vs “elite”). Some work has used continuous, comparative measures7 or a photo-sorting method20,21,24 to help overcome these challenges. Peer report methods, however, may not accurately capture peer crowd identification and may be confounded by demographic factors like race/ethnicity. Additionally, research has shown that youths often identify with more than 1 crowd, and measures that ask young people to report identification with just 1 group may be met with reluctance because youths are asked to prioritize a certain aspect of their identity over others. Finally, measuring peer crowd identification often involves researchers to identify, label, and define peer crowds, which may introduce biases, conflict with youths’ perceptions, and limit the ability of researchers to discover new peer crowds.

Although data from noncontrolled field experiments and controlled online experiments support the use of peer crowd targeting, the evidence base is still emerging, and larger randomized controlled trials are needed to further test the utility of peer crowd targeting and to shed light on several additional areas. First, most work testing peer crowd targeting has focused on tobacco use prevention.7,21,24 Tobacco use is a logical context for this work because of the correlation between risk for tobacco use and peer crowd affiliation.8 However, more work should be done to examine the extent to which peer crowd targeting is appropriate for other risk behaviors. It would also be enlightening to compare the efficacy of peer crowd targeting with that of other forms of targeting, such as the SENTAR approach,4 which targets youths on the basis of their level of sensation seeking, and to understand the synergistic effects of peer crowd targeting in combination with other forms of targeting.

Additionally, more work is needed to elucidate the mechanisms through which peer crowd targeting produces behavior change. According to some perspectives,31 peer crowd–targeted messages could make a high-risk identity salient and subsequently induce corresponding high-risk behavior. However, studies of peer crowd–targeted interventions have instead found evidence that peer crowd–targeted messages can prompt behavior change and lessen the likelihood of high-risk behavior. Our scientific knowledge would benefit from research to better understand psychological and persuasive processes underpinning this effect. Moreover, the extent to which peer crowd targeting produces macrolevel social change and the mechanisms through which this occurs are currently unexplored areas.

If peer crowd targeting is to be used for health communication campaigns, ways to assess and characterize the various peer crowds are necessary. There is currently no nationally representative data that could provide estimates of peer crowd prevalence. Knowing the percentage of youths who identify with different crowds would help practitioners select crowds to target. Further, although we present peer crowd descriptions in Table 1 to orient the reader to the concept, crowd descriptions and normative behaviors would benefit from further validation, particularly among different population subgroups. Although peer crowds are fairly temporally and geographically stable phenomena, the cultural and stylistic preferences within any 1 crowd may shift, thus necessitating just-in-time research to assess crowd preferences. Additionally, many youths identify with multiple crowds22; thus it is important to assess multiple peer crowd identification and translate this into intervention. It is similarly not clear whether there is a threshold for peer crowd identification. Although work related to social identity and behavior indicates that the more strongly individuals identify with a crowd, the more responsive they will be to a campaign targeting that crowd,7,28 it is not yet known exactly how strongly a young person must identify with a crowd for a campaign targeting that crowd to have an influence.

Finally, whereas peer crowds are an empirically and theoretically grounded concept that can be used for health education interventions, they are merely 1 way to segment the youth audience. As our review has illustrated, peer crowds are meaningful because they represent a shared culture, and this shared culture engenders common values, preferences, and behaviors among youths who identify with a particular crowd. But, individuals typically have multiple, intersectional identities, and it is important to consider how different cultural, social, or other identities interact with each other and with peer crowd identity to affect behavior. An intersectional approach to identity directs practitioners to consider peer crowds as a way to segment and target campaign materials in the context of other social and cultural categories on which identity may be based.

CONCLUSIONS

Peer crowd targeting is a useful strategy that health communication and behavior change campaigns can use to segment and target the adolescent and young adult population. The social identity and social norms approaches provide a theoretical foundation for this strategy, and the emerging evidence indicates that peer crowd targeting can increase campaign effectiveness. The Fresh Empire campaign demonstrates how peer crowd targeting can be implemented at a national level to create and disseminate tobacco prevention messages to youths. By replacing unhealthy behavioral norms with certain desirable lifestyles, peer crowd–targeted interventions can transcend race, ethnicity, and geography to create a lasting impact that resonates deeply in the culture of the target audience.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

M. B. Moran’s effort was focused solely on the theoretical aspects of tobacco prevention campaigns and is supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute for Drug Abuse (K01 award K01DA037903) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Tobacco Products. Fresh Empire is supported by the FDA (contract HHSF223201210006I).

We thank Leah Hoffman, Gem Benoza, and April Brubach for their editorial contributions.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Human participant protection was not required because this article did not involve human participants.

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Speaking of Health: Assessing Health Communication Strategies for Diverse Populations. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kreuter MW, Skinner CS. Tailoring: what’s in a name? Health Educ Res. 2000;15(1):1–4. doi: 10.1093/her/15.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slater MD. Theory and method in health audience segmentation. J Health Commun. 1996;1(3):267–283. doi: 10.1080/108107396128059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmgreen P, Donohew L, Lorch EP, Hoyle RH, Stephenson MT. Television campaigns and adolescent marijuana use: tests of sensation seeking targeting. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(2):292–296. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.2.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boslaugh SE, Kreuter MW, Nicholson RA, Naleid K. Comparing demographic, health status and psychosocial strategies of audience segmentation to promote physical activity. Health Educ Res. 2005;20(4):430–438. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noar SM. A 10-year retrospective of research in health mass media campaigns: where do we go from here? J Health Commun. 2006;11(1):21–42. doi: 10.1080/10810730500461059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moran MB, Sussman S. Translating the link between social identity and health behavior into effective health communication strategies: an experimental application using antismoking advertisements. Health Commun. 2014;29(10):1057–1066. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2013.832830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sussman S, Pokhrel P, Ashmore RD, Brown BB. Adolescent peer group identification and characteristics: a review of the literature. Addict Behav. 2007;32(8):1602–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: what is it, and what is it good for? Child Dev Perspect. 2007;1(2):68–73. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and Crisis. New York, NY: Norton; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berzonsky MD. Identity processes. In: Lerner RM, Petersen AC, Brooks-Gunn J, editors. Encyclopedia of Adolescence. New York, NY: Springer; 2011. pp. 1363–1369. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brechwald WA, Prinstein MJ. Beyond homophily: a decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. J Res Adolesc. 2011;21(1):166–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moran MB, Sussman S. Social identity and antismoking campaigns: how who teenagers are affects what they do and what we can do about it. In: Esrock SL, Walker KL, Hart JL, editors. Talking Tobacco: Interpersonal, Organizational, and Mediated Messages. New York, NY: Peter Lang;; 2014. pp. 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown BB. Adolescents’ relationships with peers. In: Lerner R, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2004. pp. 363–394. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mackey ER, La Greca AM. Adolescents’ eating, exercise, and weight control behaviors: does peer crowd affiliation play a role? J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(1):13–23. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackey ER, La Greca AM. Does this make me look fat? Peer crowd and peer contributions to adolescent girls’ weight control behaviors. J Youth Adolesc. 2008;37(9):1097–1110. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sessa FM. Peer crowds in a commuter college sample: the relation between self-reported alcohol use and perceived peer crowd norms. J Psychol. 2007;141(3):293–305. doi: 10.3200/JRLP.141.3.293-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stapleton J, Turrisi R, Hillhouse J. Peer crowd identification and indoor artificial UV tanning behavioral tendencies. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(7):940–945. doi: 10.1177/1359105308095068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashmore RD, Del Boca FK, Beebe M. “Alkie,” “frat brother,” and “jock”: perceived types of college students and stereotypes about drinking. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2002;32(5):885–907. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee YO, Jordan JW, Djakaria M, Ling PM. Using peer crowds to segment Black youth for smoking intervention. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15(4):530–537. doi: 10.1177/1524839913484470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fallin A, Neilands TB, Jordan JW, Hong JS, Ling PM. Wreaking “havoc” on smoking: social branding to reach young adult “partiers” in Oklahoma. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(1):S78–S85. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuqua JL, Gallaher PE, Unger JB et al. Multiple peer group self-identification and adolescent tobacco use. Subst Use Misuse. 2012;47(6):757–766. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.608959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.La Greca AM, Prinstein MJ, Fetter MD. Adolescent peer crowd affiliation: linkages with health-risk behaviors and close friendships. J Pediatr Psychol. 2001;26(3):131–143. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.3.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ling PM, Lee YO, Hong J, Neilands TB, Jordan JW, Glantz SA. Social branding to decrease smoking among young adults in bars. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(4):751–760. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turner JC. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory. Oxford, England: Basil Blackwell; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abrams D, Hogg MA. Social Identifications: A Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations and Group Processes. London, England: Routledge; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berkowitz AD. An overview of the social norms approach. In: Lederman LC, Stewart L, editors. Changing the Culture of College Drinking: A Socially Situated Health Communication Campaign. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press; 2005. pp. 193–214. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terry DJ, Hogg MA. Group norms and the attitude–behavior relationship: a role for group identification. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1996;22(8):776–793. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rimal RN. Modeling the relationship between descriptive norms and behaviors: a test and extension of the theory of normative social behavior (TNSB) Health Commun. 2008;23(2):103–116. doi: 10.1080/10410230801967791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGuire WJ. Input and output variables currently promising for constructing persuasive communications. In: Rice RE, Atkin CK, editors. Public Communication Campaigns. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2001. pp. 22–48. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Comello MLG. Conceptualizing the intervening roles of identity in communication effects. In: Larosa DL, Rodriguez A, editors. Identity and Communication: New Agendas in Communication. New York, NY: Routledge; 2013. pp. 168–188. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Houlihan AE, Stock ML, Pomery EA. A dual-process approach to health risk decision making: the prototype willingness model. Dev Rev. 2008;28(1):29–61. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grandpre J, Alvaro EM, Burgoon M, Miller CH, Hall JR. Adolescent reactance and anti-smoking campaigns: a theoretical approach. Health Commun. 2003;15(3):349–366. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1503_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen J. Defining identification: a theoretical look at the identification of audiences with media characters. Mass Commun Soc. 2001;4(3):245–264. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moran MB, Sussman S. Changing attitudes toward smoking and smoking susceptibility through peer crowd targeting: more evidence from a controlled study. Health Commun. 2015;30(5):521–524. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2014.902008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hafez N, Ling PM. Finding the kool mixx: how Brown & Williamson used music marketing to sell cigarettes. Tob Control. 2006;15(5):359–366. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hendlin Y, Anderson SJ, Glantz SA. “Acceptable rebellion”: marketing hipster aesthetics to sell Camel cigarettes in the US. Tob Control. 2010;19(3):213–222. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.032599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rogers EM. Diffusions of Innovations. 5th ed. New York, NY: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verkooijen KT, de Vries NK, Nielsen GA. Youth crowds and substance use: the impact of perceived group norm and multiple group identification. Psychol Addict Behav. 2007;21(1):55–61. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marcia JE. Development and validation of ego-identity status. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1966;3(5):551–558. doi: 10.1037/h0023281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hall SP. Identity status. In: Lerner RM, Petersen AC, Brooks-Gunn J, editors. Encyclopedia of Adolescence. New York, NY: Springer; 2011. pp. 1369–1377. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reed A, Forehand MR, Puntoni S, Warlop L. Identity-based consumer behavior. Int J Res Mark. 2012;29(4):310–321. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cross JR, Fletcher KL. The challenge of adolescent crowd research: defining the crowd. J Youth Adolesc. 2009;38(6):747–764. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9307-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pokhrel P, Brown BB, Moran MB, Sussman S. Comments on adolescent peer crowd affiliation: a response to Cross and Fletcher (2009) J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39(2):213–216. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9454-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]