Abstract

Objectives. To evaluate the effectiveness of a community-based liver cancer prevention program on hepatitis B virus (HBV) screening among low-income, underserved Vietnamese Americans at high risk.

Methods. We conducted a cluster randomized trial involving 36 Vietnamese community-based organizations and 2337 participants in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York City between 2009 and 2014. We randomly assigned 18 community-based organizations to a community-based multilevel HBV screening intervention (n = 1131). We randomly assigned the remaining 18 community-based organizations to a general cancer education program (n = 1206), which included information about HBV-related liver cancer prevention. We assessed HBV screening rates at 6-month follow-up.

Results. Intervention participants were significantly more likely to have undergone HBV screening (88.1%) than were control group participants (4.6%). In a Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel analysis, the intervention effect on screening outcomes remained statistically significant after adjustment for demographic and health care access variables, including income, having health insurance, having a regular health provider, and English proficiency.

Conclusions. A community-based, culturally appropriate, multilevel HBV screening intervention effectively increases screening rates in a high-risk, hard-to-reach Vietnamese American population.

Worldwide, approximately 2 billion people have been infected with the hepatitis B virus (HBV).1 Of these, about 400 million are chronically infected. HBV is the leading cause of chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma, especially in the Asia–Pacific region.2 Furthermore, an estimated 1 million people die each year from HBV and HBV-related health consequences.1,3 Although a vaccine to prevent HBV infection has been available since 1982, vaccination rates are often suboptimal in high-risk populations. Thus, HBV is a worldwide health concern with significant personal, societal, and economic costs.4

In the United States, an estimated 2.2 million residents are chronically infected with HBV,5 of which approximately 58% are Asian American. The prevalence of HBV infection is higher among Asian Americans than any other racial/ethnic group in the United States.6,7 Although Asian Americans make up about 5% of the US population, they account for more than 50% of all Americans with chronic HBV.8 The prevalence of chronic HBV and associated chronic diseases varies by Asian ethnicity and is highest among Vietnamese Americans (7%–14%).2,9,10

Because chronic HBV is usually asymptomatic over many years and HBV screening rates are low in the United States, the majority of HBV carriers are typically unaware that they are infected.4,11–13 Although HBV screening can help identify those who could be protected with vaccination, screening rates are suboptimal. In the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Race and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health study, which comprised 53 996 participants from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds, only 39.2% had ever been screened for HBV.14 Studies of Asian American populations suggest that nonscreening rates range from 53.0% to 67.5%.15–17

A systematic review of 23 studies identified Vietnamese Americans as having among the lowest screening rates of all Asian American populations.18 In response to this, the White House and federal agencies and advocacy groups in the United States have released a national action plan calling for urgent actions on HBV education and screening to identify infected individuals early in the course of their disease. Specifically, the CDC recommended HBV screening for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, a population considered to be at high risk because they have the highest incidence and mortality rates of HBV-related liver cancer.7,19–24

However, Asian Americans experience many barriers to HBV screening, including limited health care access and cultural and personal reasons. Specifically, a lack of health insurance, not having a regular physician, not knowing where to go for screening, not being able to afford copays, limited English language proficiency, and difficulty in scheduling appointments are commonly reported barriers to screening in Asian American populations.14,17,25 In addition, a lack of knowledge or misinformation regarding how HBV is spread, the benefits of testing and early treatment, and the link between HBV infection and liver cancer is often reported in this population.16,17,25 Cultural values, beliefs, and fears about stigma are also significant barriers to screening.16,17,26–28

Despite the high prevalence of HBV infection among Vietnamese Americans, combined with consistently low screening rates, very few interventions have been developed to overcome barriers to HBV screening in this population.29 Therefore, we conducted one of the first (to our knowledge) randomized, community-based intervention trials to address multilevel barriers and increase HBV screening among high-risk Vietnamese Americans. This large-scale intervention trial addressed both individual and health care system barriers through multifaceted innovative components. We have presented primary outcome findings from a National Cancer Institute–funded cluster randomized trial designed to evaluate the effects of a community-based, culturally appropriate, multilevel intervention in increasing HBV screening among Vietnamese Americans to prevent HBV-related liver cancer.

METHODS

The Center for Asian Health at Temple University has a longstanding collaborative relationship with more than 380 Asian American community-based organizations in the Eastern region of the United States, representing multiethnic Asian American subgroups. Most of these organizations are partner members of the Asian Community Health Coalition. The Vietnamese community-based organizations (VCOs) that participated in this study as part of the Asian Community Health Coalition serve important social functions, and they are an ideal milieu for obtaining information on patient accessibility to needed health services.

Vietnamese American community leaders and representatives of eligible VCOs were directly involved in the planning, development, and implementation of the project. At the initial meetings, VCO leaders and representatives discussed the health issues that most concern Vietnamese Americans, particularly the need to address HBV screening. We conducted focus groups involving community members and community advisory board meetings. We identified multilevel barriers and sociocultural factors associated with HBV screening, reviewed messages that may motivate and facilitate Vietnamese Americans to obtain HBV screening, and discussed how to revise a health intervention to best include cultural elements and themes that would be appealing to Vietnamese Americans as well as recommendations for recruitment and retention strategies.

Study Design

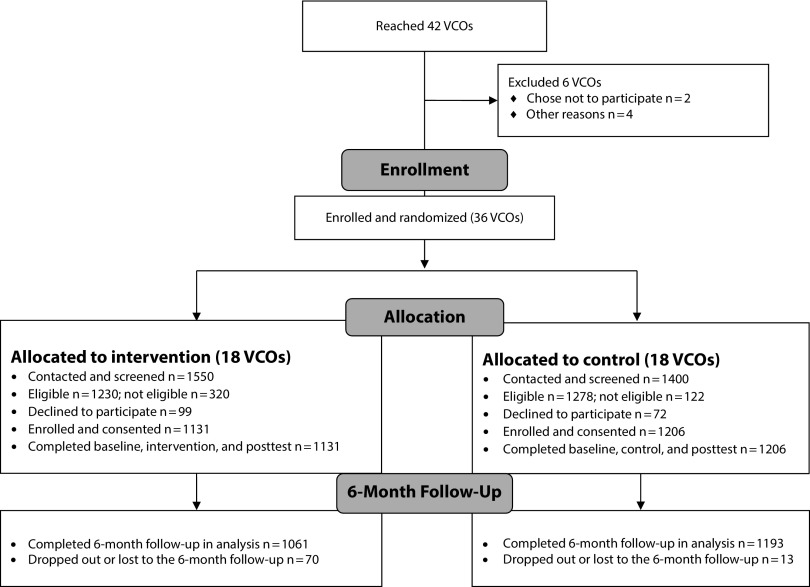

The study was a 2-arm cluster randomized trial with community-based organizations as the unit of randomization. We recruited 42 VCOs in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York City. A total of 36 VCOs consented and enrolled; we randomly assigned 18 of the VCOs to the intervention condition and 18 VCOs to the control condition (Figure 1) using a matched-pair design.30 On the basis of organization profile information provided by collaborating VCO leaders, we developed an algorithm using Stata version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) to match each pair on the basis of education, age, and geographic location.

FIGURE 1—

Study Flow Diagram

Note. VCO = Vietnamese community-based organization.

We then used a random number generator to assign each member of the pair to the 2 different groups. Following stratification, we enrolled VCO member participants who were eligible and had consented to either the intervention or the control group of their affiliated VCO group condition. We fully explained the study purpose, design, and nature to collaborating VCO leaders and designated staff at project planning meetings.

Participants

The number of Vietnamese American members in each of these 36 organizations ranged from 120 to 2500. We adopted an incremental sampling procedure during the participant recruitment stage; we recruited a minimum of 30 participants for sites with membership between 120 and 500 and an additional 10 participants for every 200-member increment. VCO leaders provided membership lists without contact information to protect confidentiality. A biostatistician selected a random sample from each list. Trained VCO leaders contacted members of the selected sample to learn whether they were interested in the study. Research assistants performed eligibility screening and obtained consent among participants who expressed interest in the study. We collected assessment data at baseline, after the intervention, and at 6-month follow-up. We validated self-report screening 6 months after the baseline.

We recruited study participants from each VCO and assessed them for eligibility on the basis of the following criteria:

self-identified Vietnamese ethnicity,

aged 18 years or older,

access to a telephone (for scheduling and contact purposes),

not currently or previously enrolled in any HBV intervention program,

never had HBV screening, and

not aware of any previous HBV infections or diagnoses.

We recruited Vietnamese American adult men and women (n = 2950) from 36 participating VCOs between 2010 and 2012. Specifically, we recruited 1550 Vietnamese men and women from 18 VCOs of the intervention condition and 1400 from 18 VCOs of the control condition. Among all recruited Vietnamese Americans who were assessed for study eligibility, 2508 met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 2337 consented and completed baseline assessment, with a 93.2% response rate (including 1131 participants for the intervention group and 1206 participants for the control group; Figure 1).

Of the participants (n = 2337) who completed the baseline assessment, 2254 participants completed the 6-month follow-up assessment and were included in the data analysis for HBV screening behavior (intervention group: n = 1061; control group: n = 1193). We excluded 83 participants from the data analysis because they dropped out before the 6-month follow-up. Therefore, the study retention rate was 96% among participants who completed baseline, intervention, and 6-month follow-up (Figure 1).

Intervention Condition

We evaluated the effectiveness of a community-based culturally and linguistically appropriate HBV screening intervention. A conceptual framework guided the intervention and incorporated components from the health belief model and social cognitive theory to address both individual-level cultural beliefs and health care system barriers.

We designed the intervention to increase HBV screening among previously unscreened individuals. Key intervention components included interactive group education, navigation services, and the engagement of community leadership and health care providers in advocacy and referrals. Specifically, bilingual community health educators delivered 1 in-person interactive education session. The session lasted about 2 hours and was delivered in a group format to 15 to 20 participants.

All group education sessions took place at VCO sites. The group education curriculum consisted of 5 components:

HBV prevalence in the United States and globally, and risk factors for HBV and liver cancer relevant to Vietnamese Americans;

misperception of HBV transmission;

the HBV infection process and liver cancer and its prevention;

HBV screening and vaccination protocols, benefits, barriers, and facilitators culturally relevant to Vietnamese Americans; and

culturally relevant strategies for communicating with health providers regarding various options for follow-up and treatment if participants are found to be HBV carriers on screening.

Before intervention, the principal investigator, key investigators, and peer health educators provided intensive training of and role play practice for bilingual community health educators on the nature of HBV infection, study protocols, delivery contents and approach, facilitation guide, and participants’ rights among other things.

Patient navigation assistance was one of the intervention components and was offered to all participants in the intervention group; bilingual patient navigators provided it to participants who requested it. The Center for Asian Health’s health professionals trained bilingual patient navigators. Patient navigation assistance included language translation, appointment scheduling, transportation, guided information related to the health care system, low-cost health services, and free HBV screening events provided by community health providers, among other things. We implemented the intervention between 2010 and 2013. We completed follow-up data collection in 2014.

Control Condition

Participants in the control group were provided with 1 group session in a format that was similar to that of the intervention group. The group session focused on general cancer education and preventive care, including the importance of receiving routine health exams and various types of cancer screening. Health educational materials were provided to control group participants, including HBV education literature available from federal agencies, which research team members who are certified translators translated into Vietnamese. In addition, we encouraged participants to schedule routine medical check-ups with their health care providers.

Six months following the baseline and intervention or control group session, we recontacted and assessed participants for their HBV screening status. Following the completion of the 6-month assessment, we offered all control group participants the opportunity to receive the intervention program.

Outcome Measures

At baseline, we collected the following demographic characteristics:

gender;

marital status;

education level;

annual household income;

health care access, such as having health insurance and a regular health care provider;

employment status; and

indicators of acculturation, including English language proficiency and participation in social cultural gatherings among other things.

The primary outcome variable was whether a participant had obtained HBV screening at the 6-month follow-up assessment. Specifically, participants were asked to respond to the following item: “Have you had a blood test for hepatitis B during the past 6 months?” with the response options “yes” or “no.” We asked study participants who reported that they had undergone HBV testing to provide consent for verification with their screening providers.

We conducted the process evaluation at different points after the intervention to document the study process and quality. Specifically, the process evaluation included a short survey assessing participant acceptance of and satisfaction with the intervention and use of patient navigation services. For quality control and treatment fidelity, we used a standardized observation form to ensure that all components of the intervention were delivered as planned. Community health educators, the principal investigator, and key research team members met regularly for monitoring and feedback.

Statistical Analysis

We followed 3 steps in our statistical analysis. First, we compared the intervention and control groups with regard to sample characteristics with cross-tabulations and the χ2 statistic if the measurement was categorical or t test if the measurement was continuous. We controlled for social demographic variables that were different at baseline (i.e., P < .05) in subsequent statistical comparisons.

Second, we conducted the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test that we used to obtain relative risk (RR) to compare HBV screening behavior at 6-month follow-up among previously unscreened participants while controlling for covariates.

Third, we conducted the χ2 test to assess HBV screening rates at 6-month follow-up for the overall effect, while controlling for sociocultural variables that were different between intervention and control at baseline. We ran all statistical tests and summary data in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Participants had a sample mean age of 55 years (SD = 15.06). About 42% of participants were male. The majority was currently married (75.0%), had a high school education or less (82.9%), and reported an annual household income of $20 000 or less (53.5%). Of the 2337 participants who enrolled in the study, 2254 (96.0%) completed the 6-month follow-up assessment. This included 1061 participants in the intervention condition and 1193 in the control condition. Eighty-three participants dropped out and were lost to the 6-month follow-up. Analyses indicated no significant differences between participants who dropped out and participants who completed the follow-up (n = 83; about 4% attrition rate; Figure 1).

Baseline characteristics of the participants in the intervention and control groups are presented in Table 1. The 2 groups were comparable with regard to gender, marital status, and education level. However, the intervention group had a significantly greater proportion of participants (42.7%) with low annual household incomes (< $10 000) than did the control group (26.3%; P < .001). In addition, in the intervention group a greater proportion of participants was uninsured (56.0%) and a greater proportion reported not having a regular physician (30.7%) compared with those of the control group (37.0% and 22.5%, respectively).

TABLE 1—

Sample Characteristics at Baseline: Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York City, 2009–2014

| Characteristic | P | Intervention (n = 1131), No. (%) or Mean ±SD | Control (n = 1206), No. (%) or Mean ±SD |

| Age, y | < .01 | 54.5 ±16.3 | 56.3 ±13.8 |

| Gender | .33 | ||

| Male | 461 (40.7) | 527 (42.7) | |

| Female | 606 (59.3) | 707 (57.3) | |

| Marriage | .22 | ||

| Married | 836 (73.9) | 919 (76.2) | |

| Never married | 198 (17.5) | 179 (14.8) | |

| Divorced or widowed | 97 (8.6) | 108 (9.0) | |

| Education | .07 | ||

| < high school | 301 (29.5) | 362 (31.2) | |

| High school graduate | 589 (57.8) | 686 (59.2) | |

| ≥ some college | 129 (12.7) | 111 (9.6) | |

| Annual household income, $ | < .001 | ||

| < 10,000 | 293 (44.2) | 226 (26.3) | |

| 10 000–20 000 | 258 (40.4) | 474 (55.1) | |

| > 20 000 | 102 (15.4) | 161 (18.7) | |

| Has health insurance | < .001 | ||

| No | 630 (56.0) | 444 (37.0) | |

| Yes | 495 (44.0) | 756 (63.0) | |

| Has a regular physician | < .01 | ||

| No | 342 (30.7) | 266 (22.5) | |

| Yes | 773 (69.3) | 916 (77.5) | |

| Employment status | < .001 | ||

| Employed | 600 (53.5) | 772 (63.9) | |

| Unemployed | 124 (11.1) | 93 (7.7) | |

| Retired or homemaker | 398 (35.5) | 343 (28.4) | |

| Speaks English | < .001 | ||

| Not at all | 447 (39.5) | 429 (35.6) | |

| Not well | 561 (49.6) | 682 (56.6) | |

| Well or very well | 123 (10.8) | 93 (7.7) | |

| Participates in social cultural gatherings | < .001 | ||

| All the time | 271 (23.9) | 422 (35.1) | |

| Sometimes | 733 (64.7) | 694 (57.8) | |

| Not at all | 128 (11.3) | 85 (7.1) |

Note. The numbers do not add to the total number of samples because of missing values. The total sample size was n = 2337.

The intervention group also had a higher proportion of unemployed individuals (11.1%) than did the control group (7.7%). Participants in the intervention were more likely to report that they did not speak English at all than were those in the control group (39.5% vs 35.6%) and reported attending social or cultural events less often than did those in the control group (23.9% vs 35.1%). Therefore, we controlled for annual household income, health insurance status, having a regular physician, English language proficiency, and participation in social or cultural events in subsequent analyses.

We assessed HBV screening behaviors at 6-month follow-up. In the intervention group, 88.12% (935 of 1061 participants) had obtained screening, whereas 11.88% (126 of 1061) had not. We were able to verify 95.10% of the self-reported screenings (889 of the 935 participants who reported obtaining HBV screening). We were able to obtain screening confirmation for self-reported HBV screening for 836 (94.10%) of the 889 participants; thus, 89.40% (836 of 935) of intervention group participants who self-reported HBV screening were verified and demonstrated agreement between self-report and verification. Of the 836 participants tested and verified, 92 (11.00%) were confirmed by HBsAg (hepatitis B surface antigen) positive to be infected with HBV.

In the control group, 4.61% (55 of 1193 participants) had obtained screening by 6-month follow-up. The screening rate was significantly higher in the intervention group (88.10%) than in the control group (4.61%; χ2[1] = 1590.2; P < .001).

Table 2 presents the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel analyses (RR and 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) for the primary study outcome controlling for the significant social demographic variables of age, income, insurance, regular physician, employment, speaking English, and social or cultural gathering participation. The intervention group had a substantially higher HBV screening rate at follow-up than did the control group (88.12% vs 4.61%). In the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel analysis, the RRs of participants receiving HBV screening by 6-month follow-up were significantly higher for the intervention group than for the control group (RR = 19.12; 95% CI = 14.75, 24.77; P < .001). After adjustment for sociodemographic variables, the RR of receiving HBV screening between the intervention and the control group decreased to 18.57 (95% CI = 13.67, 25.25; P < .001; Table 2).

TABLE 2—

Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel Analysis of Hepatitis B Screening Behavior at 6-Month Follow-Up Among Previously Unscreened Participants: Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York City, 2009–2014

| Variable | Total | Intervention | Control |

| No. clusters | 36 | 18 | 18 |

| No. participants | 2254 | 1061 | 1193 |

| Screened for HBV, % | 43.90 | 88.12 | 4.61 |

| Model 1, RR (95% CI) | 19.12 (14.75, 24.77) | 1 (Ref) | |

| Model 2, RR (95% CI) | 18.57 (13.67, 25.25) | 1 (Ref) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; HBV = hepatitis B virus; RR = relative risk. Model 2 controls for age, household income, employment status, having health insurance, having a regular physician, English speaking ability, and participation in social and cultural gatherings. The sample size was n = 2337.

In the intervention condition, 658 (62%) participants reported that they received navigation assistance from bilingual navigators to obtain HBV screening. Of those who received navigation services, 98% received assistance both for scheduling or coordinating appointments and language interpretation services; 52% of the participants reported receiving guided information about the health care system or low-cost or free screening services. Assistance with arranging appointments and language interpretation or translation services were the most common requests for support (89%).

DISCUSSION

If undetected, prevalent HBV infection among Asian Americans may cause significant morbidity and mortality, particularly from liver cancer. Liver cancer is one of the most preventable cancers and is among the few urgent health problems the White House directly highlights.19 Calling for an immediate public health response, the 2014 update to the Combat the Silent Epidemic of Viral Hepatitis action plan and presidential executive order 13515 set forth directives to address HBV in Asian American communities.31 These directives mirror the Institute of Medicine’s recommended strategies for improving access to HBV screening and treatment, highlighting the disparities in access to care observed among key at-risk groups.19 Widespread screening for at-risk populations, targeted vaccination, and greater access to treatment are highly cost-effective public health measures.11,32,33 The CDC amended and issued broader and more forceful recommendations concentrating on prevention, vaccination, and early entry into treatment and monitoring.34–37 The first step toward achieving these public health goals is HBV screening.

As demonstrated in this study, our community-based culturally appropriate multilevel HBV screening intervention had significant effects on HBV screening rates as reflected in the substantial difference in screening between the intervention group and the control group (88.1% vs 4.6%). The self-reported HBV screening rate is in high agreement with that of the validated results. Our results showed a larger intervention effect than did other HBV screening randomized trial studies. For example, in previous studies of various Asian American communities (which included Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese American participants), HBV screening rates ranged from 19% to 35% among intervention group participants.34–37

In this large-scale cluster randomized trial, we tested the efficacy of a multilevel community-based participatory intervention with interactive group education, patient navigation, and community leadership and health care provider engagement to increase HBV screening and reduce health access barriers for underserved, high-risk, and hard-to-reach Vietnamese Americans. The health belief model and social cognitive theory provided a useful structure and a conceptual framework for developing and implementing culturally appropriate intervention components.

The high screening rates of more than 88% achieved in this study may be attributed to the combined efforts of increasing community knowledge and support for HBV screening, along with providing navigation services to increase access among this underserved and low socioeconomic status population. Indeed, community awareness of HBV and efforts to reduce stigma may be important mechanisms for increasing community trust for HBV screening.38,39 Our findings also demonstrate that using a community-based participatory research approach is more likely to increase the intervention effect on the receipt of HBV screening and the sustainability of an intervention research program. It is imperative to engage community partners in all phases of the research project so that the academic–community research team can work together to better respond to the needs of targeted communities and incorporate community inputs into the program.

However, community interventions must also be matched with improved access to health care, including facilitating entry to screening services. Patient navigation has been recognized as a key element in facilitating access to cancer care and treatment, but to date navigation in the screening and prevention setting has not been extensively used. Obtaining preventive care can be a formidable challenge in underserved communities, especially for first-generation immigrants with limited English proficiency. Navigation to low-cost screening programs would be an extremely important addition to future programs designed for similar low-resource communities. This is particularly germane for individuals who have limited access to health care providers because physician recommendations are one of the most significant predictors of HBV screening7,40,41; yet many individuals from high-risk communities do not have a regular physician.

Limitations

Despite achieving a significant intervention effect, we acknowledge several limitations to this study. First, we verified self-reported screening only in the intervention group and not in the control group. However, screening rates in the control group were low (< 5%), and therefore it is unlikely that control group participants were overreporting screening uptake. Second, the 2 groups differed on several sociodemographic characteristics. Notably, the intervention group was composed of a greater proportion of individuals who were socioeconomically disadvantaged and uninsured and faced language difficulties. Participants in the control group were more likely to have health insurance and regular physicians than were those in the intervention group. Because these factors are generally associated with screening uptake and prevention behaviors, it is noteworthy that the intervention achieved such high screening rates despite these barriers.

Third, we did not have data available for a cost analysis. This should be considered in future work to inform further dissemination of the intervention. Finally, we were unable to determine the independent effects of individual program components (i.e., community health educator–led interactive group education, patient navigation, or engagement of community leadership, and health care providers in advocacy and referrals). The individual component data collection and analysis should be considered in future studies to better inform the dissemination of the intervention. However, these findings demonstrate that presenting these multicomponents together to target multiple factors with multilevel barriers within 1 cohesive intervention can contribute to significant improvements in HBV screening rates.

Conclusions

Our study contributes to the field of population-based health disparities research by providing strong evidence that a community-based culturally appropriate multilevel intervention that addresses both individual and health care system access barriers is effective in increasing HBV screening rates among Vietnamese Americans, one of the most at-risk and hard-to-reach populations in the United States. Such interventions need further tailoring for cultural relevance to be widely disseminated to other Vietnamese and Asian populations residing in the United States who experience high rates of HBV infection.

However, although HBV screening is the first step in addressing the HBV epidemic, it is not the last. Improved access to health care, including facilitating access to vaccination, eliminating delays into care, and improving follow-up after diagnosis, will also need to occur, in addition to screening. Public health efforts must address the barriers to screening and improve access to prevention and treatment to be widely effective. Beyond these measures, communities that face stigma for high rates of HBV infection may also need national awareness to help reduce this concern. This study was a pivotal step in increasing HBV screening rates and was grounded on community partnerships that improved trust by building coalitions using community-based participatory approaches.21,42 Thus this study serves as a model for future dissemination programs to eliminate disparities in HBV-related health outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute (NCI; grant R01 CA129763 to G. X. M.) and the Asian Community Cancer Health Disparities Center (grant U54 CA153513 to G. X. M.).

The authors wish to thank the Asian Community Health Coalition and its Vietnamese member organizations for their collaboration.

Note. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCI or the NIH.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This research program was approved by Temple University’s institutional review board (protocol 11187).

REFERENCES

- 1.Hepatitis B Foundation. FAQ: general info. 2016. Available at: http://www.hepb.org/patients/general_information.htm#ques3. Accessed April 7, 2016.

- 2.Nguyen K, Van Nguyen T, Shen D et al. Prevalence and presentation of hepatitis B and C virus (HBV and HCV) infection in Vietnamese Americans via serial community serologic testing. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17(1):13–20. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9975-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Hepatitis B: fact sheet. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en. Accessed April 7, 2016.

- 4.Romano L, Paladini S, Van Damme P, Zanetti AR. The worldwide impact of vaccination on the control and protection of viral hepatitis B. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43(suppl 1):S2–S7. doi: 10.1016/S1590-8658(10)60685-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen C, Holmberg SD, McMahon BJ et al. Is chronic hepatitis B being undertreated in the United States? J Viral Hepat. 2011;18(6):377–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kowdley KV, Wang CC, Welch S, Roberts H, Brosgart CL. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B among foreign-born persons living in the United States by country of origin. Hepatology. 2012;56(2):422–433. doi: 10.1002/hep.24804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral hepatitis—CDC recommendations for specific populations and settings: Asian and Pacific Islanders. 2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/populations/api.htm. Accessed April 7, 2016.

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Asian Americans and hepatitis B. 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/Features/AAPIHepatitisB. Accessed March 27, 2014.

- 9.Philbin MM, Erby LA, Lee S, Juon HS. Hepatitis B and liver cancer among three Asian American sub-groups: a focus group inquiry. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(5):858–868. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9523-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin H, Ha NB, Ahmed A et al. Both HCV and HBV are major causes of liver cancer in Southeast Asians. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013;15(6):1023–1029. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9871-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Post SE, Sodhi NK, Peng CH, Wan K, Pollack HJ. A simulation shows that early treatment of chronic hepatitis B infection can cut deaths and be cost-effective. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(2):340–348. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2008.0905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Serag HB, Kanwal F. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: Where are we? Where do we go? Hepatology. 2014;60(5):1767–1775. doi: 10.1002/hep.27222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McMahon BJ, Block J, Haber B et al. Internist diagnosis and management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Am J Med. 2012;125(11):1063–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu DJ, Xing J, Tohme RA et al. Hepatitis B testing and access to care among racial and ethnic minorities in selected communities across the United States, 2009–2010. Hepatology. 2013;58(3):856–862. doi: 10.1002/hep.26286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strong C, Lee S, Tanaka M, Juon HS. Ethnic differences in prevalence and barriers of HBV screening and vaccination among Asian Americans. J Community Health. 2012;37(5):1071–1080. doi: 10.1007/s10900-012-9541-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma GX, Shive SE, Wang MQ, Tan Y. Cancer screening behaviors and barriers in Asian Americans. Am J Health Behav. 2009;33(6):650–660. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.33.6.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma GX, Tan Y, Wang MQ, Yuan Y, Chae WG. Hepatitis B screening compliance and non-compliance among Chinese, Koreans, Vietnamese and Cambodians. Clin Med Insights Gastroenterol. 2010;3:1–10. doi: 10.4137/CGast.S3732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen-Truong CK, Lee-Lin F, Gedaly-Duff V. Contributing factors to colorectal cancer and hepatitis B screening among Vietnamese Americans. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40(3):238–251. doi: 10.1188/13.ONF.238-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colvin HM, Mitchell AE Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Department of Health and Human Services. White House Initiative on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders: HHS plan for Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (AANHPI) health. 2014. Available at: https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/Content.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=63&ID=8800. Accessed April 7, 2016.

- 21.Cohen C, Caballero J, Martin M, Weerasinghe I, Ninde M, Block J. Eradication of hepatitis B: a nationwide community coalition approach to improving vaccination, screening, and linkage to care. J Community Health. 2013;38(5):799–804. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9699-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Alliance of State & Territorial Aids Directors. The Affordable Care Act and the silent epidemic: increasing the viral hepatitis response through health reform. 2013. Available at: https://www.nastad.org/sites/default/files/Primer-ACA-Hepatitis-March-2013.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2016.

- 23.Dan C, Tai K, Wang SH et al. Addressing hepatitis B: community health centers, partnerships and the Affordable Care Act. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(2):507–512. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Department of Health and Human Services. Action Plan for the Prevention, Care and Treatment of Viral Hepatitis: Updated, 2014–2016. Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hwang JP, Fisch MJ, Zhang H et al. Low rates of hepatitis B virus screening at the onset of chemotherapy. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8(4):e32–e39. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Juon HS, Park BJ. Effectiveness of a culturally integrated liver cancer education in improving HBV knowledge among Asian Americans. Prev Med. 2013;56(1):53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiau R, Bove F, Henne J, Zola J, Fang T, Fernyak S. Using survey results regarding hepatitis B knowledge, community awareness and testing behavior among Asians to improve the San Francisco Hep B Free Campaign. J Community Health. 2012;37(2):350–364. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9452-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chao SD, Chang ET, So SK. Eliminating the threat of chronic hepatitis B in the Asian and Pacific Islander community: a call to action. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2009;10(3):507–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor VM, Yasui Y, Burke N et al. Hepatitis B testing among Vietnamese American men. Cancer Detect Prev. 2004;28(3):170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feng Z, Thompson B. Some design issues in a community intervention trial. Control Clin Trials. 2002;23(4):431–449. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(02)00206-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Department of Health and Human Services. Action Plan for the Prevention, Care and Treatment of Viral Hepatitis: Updated, 2014–2016. Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Owusu-Edusei K, Jr, Chesson HW, Gift TL et al. The estimated direct medical cost of selected sexually transmitted infections in the United States, 2008. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(3):197–201. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318285c6d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rein DB, Lesesne SB, Smith BD, Weinbaum CM. Models of community-based hepatitis B surface antigen screening programs in the U.S. and their estimated outcomes and costs. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(4):560–567. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bastani R, Glenn BA, Maxwell AE et al. Cluster-randomized trial to increase hepatitis B testing among Koreans in Los Angeles. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(9):1341–1349. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen MS, Jr, Fang DM, Stewart SL et al. Increasing hepatitis B screening for Hmong adults: results from a randomized controlled community-based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(5):782–791. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Juon HS, Lee S, Strong C, Rimal R, Kirk GD, Bowie J. Effect of a liver cancer education program on hepatitis B Screening among Asian Americans in the Baltimore–Washington metropolitan area, 2009–2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:130258. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maxwell AE, Bastani R, Glenn BA et al. Developing theoretically based and culturally appropriate interventions to promote hepatitis B testing in 4 Asian American populations, 2006–2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E72. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoo GJ, Fang T, Zola J, Dariotis WM. Destigmatizing hepatitis B in the Asian American community: lessons learned from the San Francisco Hep B Free Campaign. J Cancer Educ. 2012;27(1):138–144. doi: 10.1007/s13187-011-0252-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hsu L, Bowlus CL, Stewart SL et al. Electronic messages increase hepatitis B screening in at-risk Asian American patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58(3):807–814. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2396-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nguyen TT, McPhee SJ, Stewart S et al. Factors associated with hepatitis B testing among Vietnamese Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(7):694–700. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1285-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor VM, Yasui Y, Burke N, Chloe JH, Acorda E, Jackson JC. Hepatitis B knowledge and testing among Vietnamese-American Women. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(4):761–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ma GX, Daus GP. Health interventions. In: Trinh-Shevrin C, Islam NS, Rey MJ, editors. Asian American Communities and Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009. pp. 443–463. [Google Scholar]