Abstract

Ambient energy, niche conservatism, historical climate stability and habitat heterogeneity hypothesis have been proposed to explain the broad-scale species diversity patterns and species compositions, while their relative importance have been controversial. Here, we assessed the relative contributions of contemporary climate, historical climate changes and habitat heterogeneity in shaping Salix species diversity and species composition in whole eastern Asia as well as mountains and lowlands using linear regressions and distance-based redundancy analyses, respectively. Salix diversity was negatively related with mean annual temperature. Habitat heterogeneity was more important than contemporary climate in shaping Salix diversity patterns, and their relative contributions were different in mountains and lowlands. In contrast, the species composition was strongly influenced by contemporary climate and historical climate change than habitat heterogeneity, and their relative contributions were nearly the same both in mountains and lowlands. Our findings supported niche conservatism and habitat heterogeneity hypotheses, but did not support ambient energy and historical climate stability hypotheses. The diversity pattern and species composition of Salix could not be well-explained by any single hypothesis tested, suggesting that other factors such as disturbance history and diversification rate may be also important in shaping the diversity pattern and composition of Salix species.

Understanding the macro-scale species diversity patterns and the underlying mechanisms is one of the central challenges in ecology and biogeography1,2. In spite of theoretical advancement and a large number of studies in the last a few decades, many controversies still remain in the current literature. In order to determine the relative importance of mechanisms of the species diversity patterns, it is equally important to explore the species composition across large spatial scales in addition to exploring species diversity (i.e. species number).

Species diversity generally decreases with latitude and this pattern has been largely shaped by contemporary climate. One of the most widely studied hypotheses is the ambient energy hypothesis, which states that ambient energy imposes environmental carrying capacity on the number of individuals and consequently on species diversity3,4. It predicts that species diversity is positively correlated with the environmental temperature. This hypothesis has been tested widely and strong positive species diversity-temperature relationships have been reported for different taxonomic groups (e.g. birds5 and woody plants6).

However, recent studies have shown that species diversity-climate (including diversity-energy and diversity-water) relationships varies across clades with different evolutionary history due to niche conservatism7, and hence supported niche conservatism hypothesis8. Particularly, niche conservatism hypothesis regards that the latitudinal gradients of species diversity is rooted in the evolution of particular clades. Specifically, this hypothesis predicts that species diversity for a given clade will be low in regions where the climate conditions deflect from the clade’s ancestral niche, because species have difficulties to evolve adaptions to new climatic niches8,9,10. According to niche conservatism hypothesis, species originated in tropical regions tend to show strong positive diversity-temperature relationship while clades originated in temperate regions show negative diversity-temperature relationship11,12,13. However, it still remains controversial whether contemporary climate drives species diversity through the control of ambient energy or through niche conservatism.

In addition to the controversy on the relative contribution of contemporary climate vs. deep-time evolution, many authors proposed that climate changes since the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) (ca. 21,000 years before present) also influence species diversity patterns14,15. Therefore, the place experiencing the most severe climate changes have less species (i.e. the history climate stability hypothesis)16. Studies on the distribution of European trees found that climate changes since the LGM have led to the confinement of species’ distribution ranges to the Mediterranean regions17,18, and many species still do not inhabit the climatically suitable regions in northern Europe due to dispersal limitation19. In addition to species diversity, climate changes also significantly influence species composition20,21. Understanding how species composition responds to climate changes may improve our ability to predict novel communities under future climate change scenarios21. However, most of previous studies have focused on the effects of historical climate changes on species diversity, while the effects of historical climate changes on species composition remain poorly understood.

Habitat heterogeneity hypothesis predicts that topographic heterogeneity (e.g. elevation range and slope) contribute to the variation of species diversity22,23. Previous study on bird richness in South America showed that the model including topography relief exhibited the highest explanatory power24. Habitat heterogeneity may influence species diversity through the increase of available ecological niches which support more species3,25 and enhanced diversification due to the effects of meso-scale climate gradients26. However, the relative importance of habitat heterogeneity and climate on species diversity and composition is controversial.

Compared with surrounding lowlands, mountains have much higher topographical heterogeneity and cooler climate (especially cooler summer) because with every 100 meters rise in the altitude, the atmospheric temperature decreases by about 0.5 to 0.6 °C. In addition, mountains experience less human disturbance than the lowlands27 and could act as refuges both in the past and future. Mountains therefore have been the focus of conservation efforts27,28. Comparison of the determinants of species diversity and species composition in mountains vs. lowlands may enhance for nature conservation efforts in global mountains.

Salix is one of the main groups of woody plants in the North Temperate Zone29,30,31,32. The genus Salix consists of about 450–520 species of shrubs and trees31. The vast majority of Salix species are important components in riparian zone of desert, plain and mountains. They are also dominant species in alpine shrubland and cushion vegetation. Fossil evidence suggests that Salix originated in late Cretaceous in the temperate region of the northern Hemisphere33,34,35. With regard to their temperate origination, following niche conservatism hypothesis, we expect that the energy related variables would be negatively correlated with Salix diversity. Moreover, many Salix species are found in mountain slopes of eastern Asia32. Therefore, in addition to niche conservatism, we predict that habitat heterogeneity plays an important role in shaping Salix diversity pattern in eastern Asia. However, the quantitative assessment of the pattern of Salix diversity in eastern Asia and its relationships with climate and habitat heterogeneity remained largely elusive.

In this study, using the distribution maps of 313 Salix species in eastern Asia, we aimed to (1) assess the patterns of Salix species diversity and composition, (2) explore the relationship between species diversity/composition and environment (i.e. contemporary climate, historical climate changes and habitat heterogeneity). In our analysis, the following questions were addressed: (1) which hypothesis (i.e. ambient energy, niche conservatism, historical climate stability and habitat heterogeneity) dominates the patterns of Salix diversity? (2) What is the relative contribution of contemporary climate, historical climate changes and topographic heterogeneity in shaping Salix species composition? (3) Do the answers to these two questions differ between mountains and lowlands?

Materials and Methods

Salix species distribution data

In this study, the species distributions of Salix in eastern Asia were compiled from various resources (see below). Here, the eastern Asia referred to China, Mongolia, Asian part of Russia and central Asia. The distributions of Salix in China were obtained from the Atlas of Woody Plants in China36 and National Specimen Information Infrastructure (NSII) (http://www.nsii.org.cn/). Salix distribution in Mongolia was obtained from Virtual Guide to the Flora of Mongolia Plant Database as Practice Approach (http://greif.uni-greifswald.de/floragreif/), and the data of the Asian part of Russia and central Asia were from Woody Plants of the Asian Part of Russia and Flora of Soviet Union (I, II and III). In total, there are 17,189 county-level distribution records in Atlas of Woody Plants in China and 7,181 georeferenced specimen records for Salix distribution in China and 284 digitized distribution maps for those in Mongolia, Asian part of Russia and central Asia. To eliminate the influence of area on the estimation of species diversity, the species distribution data were gridded into an equal-area grid with grain size of 100 × 100 km. We excluded grid cells with land area located on the borders or along coasts that have land area less than 2500 km2. As a result, 2685 grid cells were finally included in the following analyses. We also conducted all the analyses using at 50 × 50 km grid cells, and all results are consistent. Therefore, we reported the results based on the grid of 100 × 100 km in the manuscript, and those based on the grid of 50 × 50 km were in Supplementary Materials (Tables S1–S2, Figs S1–S3).

Environmental data

We obtained contemporary climate and GLM climate data with the resolution of 30 arc-second from the WorldClim website (www.worldclim.org/)37. The contemporary climate data include mean monthly temperature and precipitation, mean annual temperature (MAT), mean temperature of coldest quarter (MTCQ), mean temperature of driest quarter (MTDQ), mean annual precipitation (MAP) and mean precipitation of driest quarter (MPDQ). Then using the mean month temperature and precipitation, we estimated annual rainfall (RAIN) as the total precipitation of the months with mean monthly temperature >0 °C38. We also obtained the annual potential evapotranspiration (PET) and actual annual evapotranspiration (AET) from CGIAR-CSI Global PET database (www.cgiar-csi.org/data/global-aridity-and-pet-database)39 and CGIAR-CSI Global Soil-Water database (http://www.cgiar-csi.org/data/global-high-resolution-soil-water-balance)40. The LGM climate data include the mean annual temperature and mean annual precipitation during LGM which calculated based on MIROC-ESM model. To reflect the historical climate changes, we calculated the anomaly of mean annual temperature and mean annual precipitation (MAT anomaly and MAP anomaly) as contemporary mean annual temperature and contemporary mean annual precipitation minus those at the Last Glacial Maximum respectively (Table S3).

We used elevational range and mean slope of each grid cell to represent habitat heterogeneity using the Digital Elevation Model derived from Global 30 Arc-second Elevation (GTOPO30) of U.S. Geological Survey (https://lta.cr.usgs.gov/GTOPO30)41. Elevational range was estimated as the difference between the maximum and minimum elevations within each 100 × 100 km grid cell. Slope was calculated with the Slope Tool in the spatial analysis module of ArcGIS 10.0 (ESRI, Inc., Redlands, California, USA). We first calculated the slopes within the study region at the spatial resolution of 1 × 1 km and then took the average slope of all 1 × 1 km grid cells within each 100 × 100 km grid cell.

Mountains vs. lowlands

We defined mountains following the criterion of United Nations Environmental Program/World Conservation Monitoring Centre42, which includes the following criteria. Particularly, a grid cell was counted as mountain if 1) its mean elevation is >2500 m; or 2) its mean elevation is 1500–2500 m and mean slope is >2°; or 3) its mean elevation is 300–1500 m and elevational range is >300 m. Following this criteria, 62.0% of 100 × 100 km grid cells were defined as mountains (Fig. 1a).

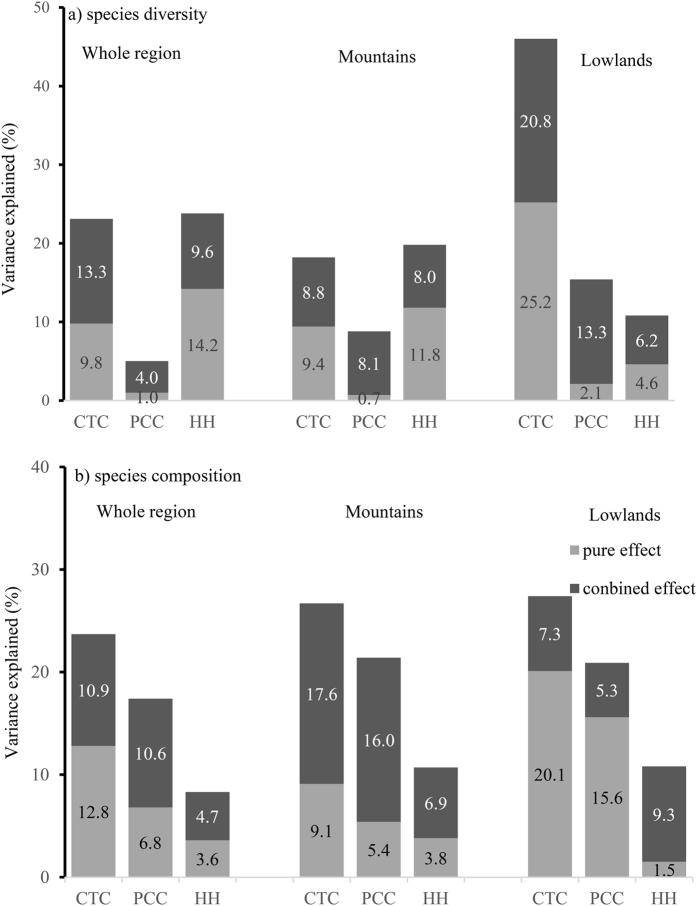

Figure 1. The distribution pattern of Salix species diversity in eastern Asia estimated in an equal-area grid of 100 × 100 km and the topography map of eastern Asia.

(a) The topography map; b) the distribution pattern of Salix diversity. The maps were created in ArcGIS 10 (http://www.esri.com/software/arcgis). The topography map in the figures was generated based on Global 30 Arc-second Elevation (GTOPO30) of U.S. Geological Survey (https://lta.cr.usgs.gov/GTOPO30).

Data analyses

Regressions for species diversity

General linear models were used to assess the explanatory power of each climate and habitat variable for Salix species diversity pattern in the whole study region, mountains and lowlands, respectively. Species diversity are square-root transformed to improve normality following previous study43. The spatial autocorrelation in species diversity could inflate type I error, and subsequently the significance levels of the statistical tests for regression models. Therefore, we used modified t-test to test the significance of all regression coefficients44.

Distance-based redundancy analysis for species composition

Species composition for Salix in the whole study region, mountains and lowlands were analyzed separately using distance-based redundancy analysis (db-RDA). The db-RDA that allows non-Euclidean dissimilarity indices (e.g. Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index and Manhattan index) is an extension of the classical redundancy analysis45. We selected Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index in this study, as it is less sensitive to the number of species and species absence46.

Variance partitioning

To further compare the relative effects of different groups of factors (i.e. contemporary climates, historical climate changes and habitat heterogeneity) in shaping species diversity pattern and species composition, we conducted variance partitioning based on partial regressions and partial db-RDA respectively. Using partial regressions, we separated the pure effects of each group of predictors from the combined effects that cannot be ascribe to only one group of predictor due to spatial multicollinearity as follows: (a) pure contemporary climate effects; (b) pure historical climate change effects; (c) pure habitat heterogeneity effects; (d) combined effects of contemporary climate and historical climate changes; (e) combined effects of historical climate change and habitat heterogeneity; (f) combined effects of contemporary climate and habitat heterogeneity; (g) combined effects of contemporary climate, historical climate changes and habitat heterogeneity. As the four frequently-used energy-related variables (i.e. MAT, MTCQ, MTDQ and PET) and four water related variables (i.e. MAP, MPDQ, RAIN and AET) are strongly correlated with each other, we select only one variable from each group to represent contemporary climate in the subsequent analyses to eliminate the influences of multicollinearity on regression analysis. We examined all the 16 possible combinations of one energy-related variable and one water-related variable into regressions/db-RDA and only selected the combinations with the highest adjusted R2.

Results

Patterns of Salix species diversity in eastern Asia

There were 313, 308 and 174 Salix species in the whole eastern Asia, mountains and lowlands, respectively. The average Salix diversity within grid cells in the whole region, mountains and lowlands were 16 (0–96), 19 (0–96) and 12 (0–40), respectively. The area with the highest species diversity were located in the eastern Tibetan Plateau, Hengduan Montains and its adjacent regions (even extending northward to Shaanxi and Gansu provinces), Northwest of Xinjiang (Tianshan mountain region), northwest of Mongolia, Stanovoy Range and Northeast China (Fig. 1a). The Salix diversity in mountains was generally higher than in lowlands (Fig. 1a and b). Except for northeastern China, most of the diversity centers of Salix were located in mountains (Fig. 1a and b). In contrast, the Salix diversity was relatively low in the western Tibetan Plateau, eastern and southern China and Turan Plain (Fig. 1a).

Environmental determinants of Salix diversity

The direction of the effects of environmental variables (i.e. positive vs. negative effects) on Salix diversity was consistent across different regions (Table 1). The species diversity decreased with energy-related variables, indicating that Salix diversity is higher in colder than warmer regions (Table 1). In contrast, Salix diversity was positively correlated with water availability in all three regions (Table 1). MAT anomaly and MAP anomaly were positively correlated with Salix diversity (Table 1), indicating that regions where climate were colder and drier during the LGM than today tended to have more Salix species than other places. The two variables of topographic heterogeneity (i.e. mean slope and elevational range) were significantly positively correlated with Salix diversity.

Table 1. Explanatory power (R2) of the predictors for Salix species diversity with a spatial resolution of 100 × 100 km evaluated by general linear models in the whole study region, mountains and lowlands seperately.

| Whole region | Mountains | Lowlands | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modern climate | |||

| MAT | 8.2% (−)* | 2.5% (−) | 31.9% (−)** |

| MTCQ | 7.4% (−) | 2.4% (−) | 33.8% (−)*** |

| MTDQ | 15.3% (−)** | 6.3% (−)* | 44.4% (−)*** |

| PET | 7.2% (−)* | 2.8% (−) | 32.5% (−)*** |

| MAP | 1.0% (+) | 3.1% (+) | 0.5% (+) |

| RAIN | 1.0% (+) | 2.5% (+) | 2.4% (+) |

| PDQ | 1.0% (+) | 0.2% (+) | 0.2% (+) |

| AET | 1.8% (+) | 4.8% (+)*** | 0.2% (+) |

| Historical Climate change | |||

| MAT Anomaly | 0.9% (+) | 0.1% (+) | 15.5% (+)** |

| MAP Anomaly | 5.0% (+)* | 8.4% (+)*** | 6.8% (+) |

| Habitat heterogeneity | |||

| Mean slope | 22.7% (+)*** | 19.3% (+)*** | 10.3% (+) |

| Elevation range | 15.6% (+)*** | 9.7% (+)*** | 6.1% (+) |

Modified-T tests were used to test the significance. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

However, the primary determinants of Salix diversity varied in different regions. Mean slope was the strongest single predictor for Salix diversity in the whole region and in mountains, accounting for 22.7% and 19.3% of the variance in species diversity respectively. In contrast, MTDQ was the strongest single predictor for species diversity in lowlands and explained 44.4% of species diversity variation. It is noteworthy that the R2 of MAP, historical climate change variables and habitat heterogeneity variables were all below 20% in mountains and lowlands (Table 1).

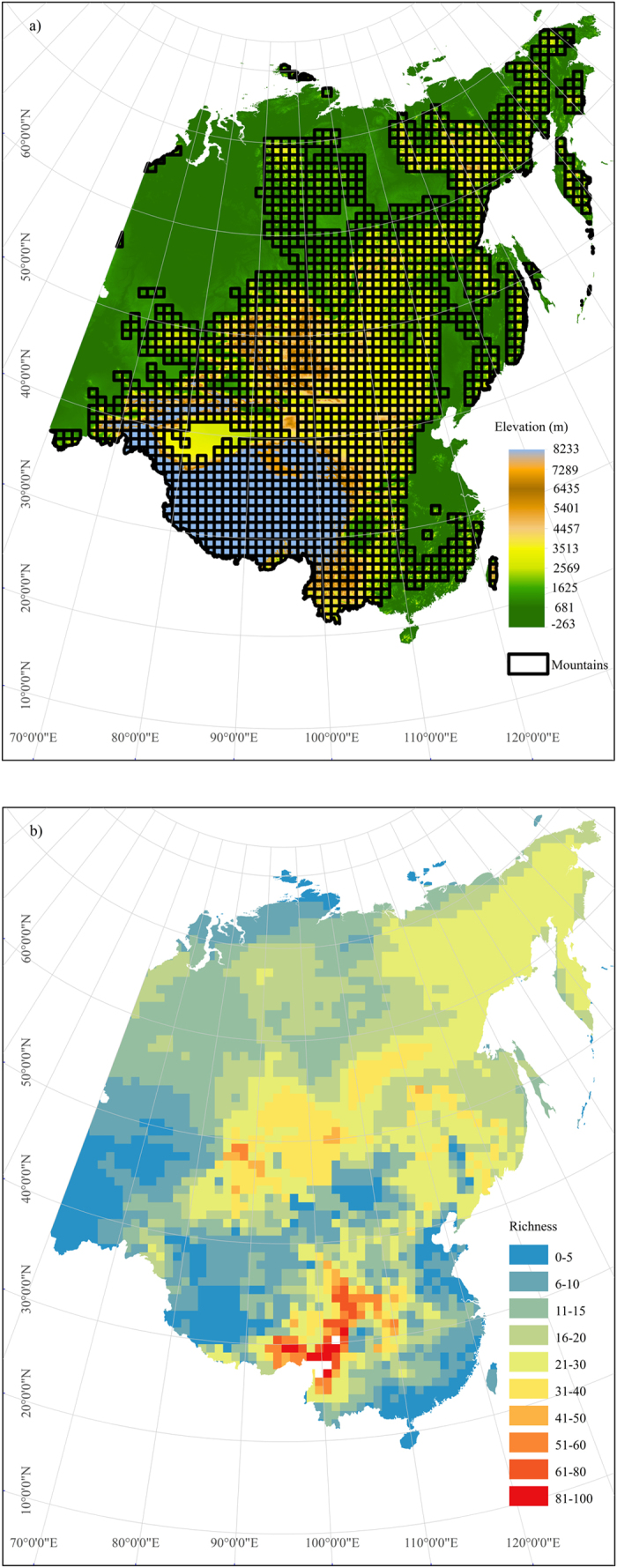

The variance partitioning analysis indicated that the pure effects of habitat heterogeneity accounted for 14.2% of the variance of Salix diversity in the whole eastern Asia, while the pure effects of historical climate change accounted for only 1.0%. The pure effects of contemporary climate accounted for 9.8% of species variance of Salix diversity patterns (Figs 2a and S4). The relative influences of contemporary climate, historical climate changes and habitat heterogeneity on species diversity were different in mountain and lowland. In mountains, the contemporary climate explained 18.2% of Salix species diversity variance. In lowlands, the exploratory power of contemporary climate was much higher (46.0%) (Figs 2a and S4).

Figure 2. The pure and combined effect of contemporary climate (CTC), historical climate changes (PCC) and habitat heterogeneity (HH) in shaping Salix species diversity and species composition in the whole region, maintains and lowlands of eastern Asia.

1) Species diversity; (b) species composition. The gray bars indicate the pure effect and black ones indicate the combined effect.

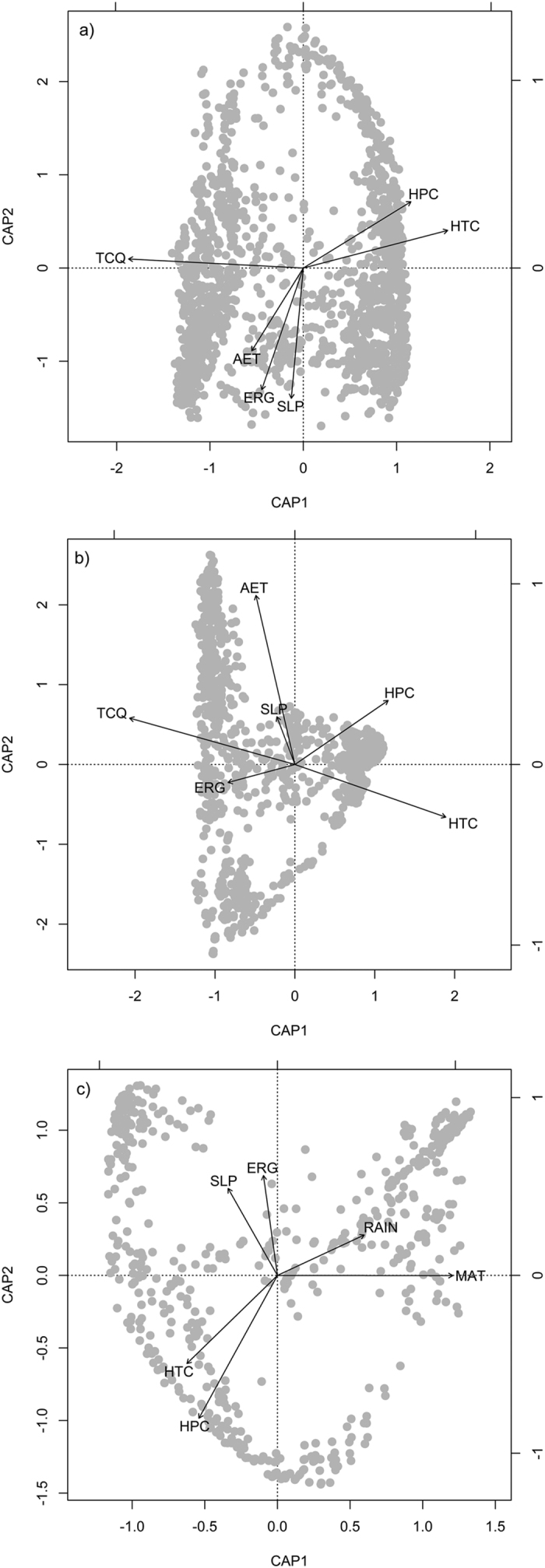

Environmental determinants of Salix species composition

Variables of habitat heterogeneity were always less important than historical climate changes and historical climate changes were always less important than contemporary climate in explaining Salix species composition in the whole region, mountains and lowlands. The habitat heterogeneity only explained ca. 10% variance in species composition (Figs 2b and S5). The variance partitioning analysis showed that contemporary climate accounted for about 9.1–20.1% of the variance in Salix species composition when the effects of historical climate changes and habitat heterogeneity were controlled for, in the whole region, mountains and lowlands (Fig. 2b). Historical climate changes accounted for 15.6% of species variance in lowlands (Figs 2b and S5) after other factors were controlled for. The first db-RDA axis accounted for about 20.0% variance in species composition (Table 2). Overall, the first db-RDA axis was most strongly correlated with MAT/MTCQ, MAT anomaly and MAP anomaly gradients (Table 2 and Fig. 3a,b,c and d).

Table 2. Biplot scores for constraining variables for the first axes in distance-base redundancy analyses.

| The whole region | Mountains | lowlands | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total variance explained by the first canonical axes | 20.0% | 23.1% | 21.0% |

| MAT | — | — | 0.98 |

| MTCQ | −0.93 | −0.91 | — |

| AET | −0.27 | −0.22 | — |

| RAIN | — | — | 0.49 |

| MAT anomaly | 0.77 | 0.83 | −0.51 |

| MAP anomaly | 0.57 | 0.51 | −0.44 |

| Mean slope | −0.06 | −0.10 | −0.27 |

| Elevation range | −0.22 | −0.37 | −0.08 |

Figure 3. Biplots of distance-based redundancy analysis showing the relationships between Salix species composition and environmental factors at the spatial resolution of 100 × 100 km in eastern Asia.

(a) The whole region; (b) mountains; (c) lowlands. MAT, mean annual temperature; TCQ, mean temperature of coldest quarter; AET, actual annual evapotranspiration; RAIN, total precipitation of the months with mean monthly temperature >0 °C; HTC, anomaly of temperature between the Last Glacial Maximum and the present; HPC, anomaly of precipitation between the Last Glacial Maximum and the present; SLP, mean slope; ERG, elevation range.

Discussions

In this study, we found that mountains generally harbor more Salix species than lowlands. This is consistent with previous reports that regard mountains as species diversity centers of different groups25,47,48. Previous studies have shown that habitat heterogeneity usually contributes less to large-scale species diversity patterns than climate5,47,49. However, we found that contemporary climate is the primary determinants of Salix diversity pattern only in lowlands, while mean slope is the primary predictor of Salix species diversity in the whole eastern Asia. This is consistent with the finding for birds in Andes24. The sites with higher mean slope may imply more riparian habitats that are ideally suitable for Salix species. It may also indicate more frequent disturbance events such as landslide and mountain torrents, which creates new space for pioneer species like Salix to colonize. Habitat heterogeneity influences Salix species distribution probably through the control of the number of available niches in local sites24.

More interestingly, we found that contemporary climate accounted for much more variance in Salix species composition than habitat heterogeneity. These results suggest that contemporary climate may primarily act as environment filtering forces in shaping individual Salix distributions and influence species composition by filtering species according to their different climate preferences50.

We obtained negative Salix diversity-temperature relationships in this study. Especially in lowland region, MTDQ was the strongest single predictor of Salix diversity pattern. Similarly to our results, previous studies have also found that Salix diversity in Europe51 and Fenoscandia52 increases with latitude and is negatively correlated with mean annual temperature51. Our results together with previous findings indicate a globally consistent relationship between Salix species diversity and temperature and suggest that the mechanisms underlying Salix diversity may be the same across different continents.

Given the temperate origination of Salix34,53, such negative diversity-temperature relationship provides support for niche conservatism hypothesis other than ambient energy hypothesis. The contemporary climate may not influence species diversity via the control of resource availability in a region, as suggested by ambient energy hypothesis5. In contrast, this is in accordance with the predictions of the niche conservatism hypothesis, which states that the species diversity of a clade decreases with the departure of climate conditions from its ancestral climatic niche8,9,10. Fossil evidence from the late Cretaceous to early Tertiary in northeast China suggest that Salix originated in a temperate-like climate conditions33,53. With regard to temperate origination, Salix, therefore, evolved strong cold tolerances29,54,55. Previous study showed that Salix twigs could survive freezing temperatures as low as −50 °C and this winter hardiness has been reported even for Salix growing in tropical and subtropical regions54,56. As a clade with temperate-origination, Salix species require a period of chilling to de-acclimatize and break bud. In warmer subtropical and tropical regions, many Salix species may, therefore, not be able to leaf out, produce flowers or regenerate28,57. In other words, Salix species are less suitable to thrive in low latitude where the climate is much warmer. This could explain why Salix species are widely distributed in temperate region of Northern Hemisphere and only mountainous regions of subtropical and tropical regions where climate is much cooler.

However, the high species diversity in Himalaya-Hengduan Mountains seem difficult to be simply explained by niche conservatism hypothesis or by a great number of available ecological niches in this region (i.e. habitat heterogeneity hypothesis) alone. Other variables related with historical and evolutionary processes were not fully considered in this analysis and may significantly contribute to high Salix species diversity. Among different historical and evolutionary processes, the uplift of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau may have played an important role in promoting rapid diversification of Salix species in the Himalaya-Hengduan Mountains and hence making this area as one of the Salix diversity centers in the world. Enhanced speciation rate in the Himalaya-Hengduan Mountains have also been found for many other taxonomic groups (e.g. Larix58; Rhododendron subgenus Hymenanthes59). These findings together with our results suggest that the Himalaya-Hengduan Mountains may have acted as species cradle not only for Salix, but also for many other groups. Future studies based on molecular phylogenies are needed to further reveal the changes in diversification of Salix through time in the Himalaya-Hengduan Mountains.

Our analysis indicated that MAT anomaly is weakly positively related with Salix diversity. These results do not follow the predictions of the history climate stability hypothesis which states that strong historical climate changes reduce the current species diversity15,16. We hypothesize that Salix with strong freezing tolerance may have found suitable habitats in northern regions during the LGM where the historical climate changes were much stronger than the southern regions. Previous studies18,60,61 have shown that many boreal species were also distributed in the central and eastern Europe including Russian Plain during the LGM. Salix produces a large number of tiny and light seeds. The seeds are enveloped by soft cottony hairs in a ring structure which facilitate long-distance dispersal via wind or by water current62. Strong dispersal ability may have facilitated re-colonization of Salix species since the LGM. This hypothesis is consistent with the previous findings on European plant distribution. Specifically, studies on the European plants found that species with strong dispersal ability recolonized most climatically suitable areas in northern Europe after the LGM, while those with weak dispersal ability retained in the southern Europe63.

We also detected signals of historical climate changes on Salix species composition in eastern Asia. Previous studies showed that species compositions could keep track with climate changes20,21. Species tolerance to climate changes and the migration rate varies among species and the ability of species to track with climate changes are different21. Strong historical climate changes may have possibly made an unsuitable condition for some Salix species that have weak tolerance to climate changes. In addition, Salix species are pioneer species32, which quickly occupies new open habitat. Strong historical climate changes in the high latitude may have create vacant habitats for pioneer Salix to colonize and persist and hence shifting the species compositions of Salix. Previous studies based on pollen evidences pointed out that Salix species were widely distributed in the Arctic regions during warmer post-LGM periods64,65. In the recent decades, the Arctic regions have experienced rapid climate warming than other regions. The warming climate could lengthen the growing seasons of shrubs and increase the nutrients availability via enhanced microbial activity66. Salix is one of the major groups in pan-Arctic vegetation. The recent and future climate warming could remarkably influence the distribution and composition of Salix species, thereby bringing about great changes in the vegetation structure and function in pan-Arctic regions. However, the number of relevant studies in this direction are still quite few67.

Summary

In this study, we found evidence for niche conservatism, historical climate changes and habitat heterogeneity to explain the diversity and species composition of Salix species in eastern Asia. However, other important factors such as disturbance history, diversification rate, soil moisture regime of local habitat68 and herbivores69 were not included in the analyses due to problems in obtaining data. In addition, Salix species are typical pioneer plants with strong dispersal and colonization abilities, and are able to fill a newly created or empty habitat. Therefore, many Salix species could easily cover a wide elevational and latitudinal range29,30,31,32. Particularly because of this tendency of Salix, variation in species distribution could not be easily captured by a single group of environmental factor in this study.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Wang, Q. et al. Historical factors shaped species diversity and composition of Salix in eastern Asia. Sci. Rep. 7, 42038; doi: 10.1038/srep42038 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (#31522012, #31470564, #31500337 and #31200329), and China postdoctoral science foundation (#2016M591008). We thank Dr. C Rahbek and Dr. D Sandanov for discussion.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions Q.W. and Z.W. conceived the idea and wrote the main text. Q.W., X.S., Y.L. and Z.W. collected the data. Q.W and X.S. performed the data analysis. N.S., X.S., S.W and X.X. contributed to the writing.

References

- Rosenzweig M. L. Species diversity in space and time. (Cambridge University Press., 1995). [Google Scholar]

- Qian H. & Ricklefts R. Large-scale processes and the Asian bias in species. Nature. 407, 180–182, doi: 10.1038/35025052 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie D. J. Energy and large-scale patterns of animal- and plant-species richness. The American Naturalist 137, 27–49, doi: 10.1086/285144 (1991). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Latham R. E. & Ricklefs R. E. Global patterns of tree species richness in moist forests: energy-diversity theory does not account for variation in species richness. Oikos 67, 325–333, doi: 10.2307/3545479 (1993). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins B. A. Productivity and history as predictors of the latitudinal diversity gradient of terrestrial birds. Ecology 84, 1608–1623, doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2003)084[1608:PAHAPO]2.0.CO;2 (2003). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Fang J., Tang Z. & Lin X. Patterns, determinants and models of woody plant diversity in China. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 278, 2122–2132, doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.1897 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Wang Z., Rahbek C., Lessard J.-P. & Fang J. Evolutionary history influences the effects of water–energy dynamics on oak diversity in Asia. Journal of Biogeography 40, 2146–2155, doi: 10.1111/jbi.12149 (2013). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiens J. J. Historical biogeography, ecology and species richness. Trends in ecology & evolution (Amsterdam) 19, 639–644, doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.09.011 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue M. J. A phylogenetic perspective on the distribution of plant diversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105, 11549–11555, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801962105 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiens J. J. Niche conservatism as an emerging principle in ecology and conservation biology Niche conservatism, ecology, and conservation. Ecology letters 13, 1310–1324, doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01515.x (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison S. & Grace J. Biogeographic affinity helps explain productivity‐richness relationships at regional and local scales. The American Naturalist 170, S5–S15, doi: 10.1086/519010 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley L. B. et al. Phylogeny, niche conservatism and the latitudinal diversity gradient in mammals. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 277, 2131–2138, doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.0179 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher-Lalonde V. et al.The weakness of evidence supporting tropical niche conservatism as a main driver of current richness–temperature gradients. Global Ecology and Biogeography 24, 795–803, doi: 10.1111/geb.12312 (2015). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Svenning J.-C. & Skov F. Limited filling of the potential range in European tree species. Ecology Letters 7, 565–573, doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00614.x (2004). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huntley B. et al. Explaining patterns of avian diversity and endemicity: climate and biomes of southern Africa over the last 140,000 years. Journal of Biogeography 43, 874–886, doi: 10.111/jbi.12714 (2016). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Araújo M. B. et al. Quaternary climate changes explain diversity among reptiles and amphibians. Ecography 31, 8–15, doi: 10.1111/j.2007.0906-7590.05318.x (2008). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Svenning J.-C., Normand S. & Kageyama M. Glacial refugia of temperate trees in Europe: insights from species distribution modelling. Journal of Ecology 96, 1117–1127, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2008.01422.x (2008). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Svenning J.-C., Normand S. & Skov F. Postglacial Dispersal Limitation of Widespread Forest Plant Species in Nemoral Europe. Ecography 31, 316–326, doi: 10.1111/j.0906-7590.2008.05206.x (2008). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Svenning J.-C. & Skov F. Could the tree diversity pattern in Europe be generated by postglacial dispersal limitation? Ecology Letters 10, 453–460, doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01038.x (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai F., Sang W. & Axmacher J. C. Forest vegetation responses to climate and environmental change: A case study from Changbai Mountain, NE China. Forest Ecology and Management 262, 2052–2060, doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2011.08.046 (2011). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand R. et al. Changes in plant community composition lag behind climate warming in lowland forests. Nature 479, 517, doi: 10.1038/nature10548 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr J. T. Habitat heterogeneity as a determinant of mammal species richness in high-energy regions. Nature 385, 252–254, doi: 10.1038/385252a0 (1997). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rahbek C. & Graves G. R. Detection of macro-ecological patterns in South American hummingbirds is affected by spatial scale. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 267, 2259–2265, doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1277 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahbek C. & Graves G. R. Multiscale assessment of patterns of avian species richness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98, 4534–4539, doi: 10.1073/pnas.071034898 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein A., Gerstner K. & Kreft H. Environmental heterogeneity as a universal driver of species richness across taxa, biomes and spatial scales. Ecology Letters 17, 866–880, doi: 10.1111/ele.12277 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C. & Eastwood R. Island radiation on a continental scale: Exceptional rates of plant diversification after uplift of the Andes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103, 10334–10339, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601928103 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguesbravo D., Araujo M. B., Romdal T. S. & Rahbek C. Scale effects and human impact on the elevational species richness gradients. Nature 453, 216–219, doi: 10.1038/nature06812 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korner C. et al. Where, why and how? Explaining the low temperature range limits of temperate tree species. Journal of Ecology 104, 1076–1088, doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12574 (2016). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newsholme C. Willows: The genus salix., (Timber Press, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- Skvortsov A. Willows of Russia and adjacent countries. (University of Joensuu, 1999). [Google Scholar]

- Argus G. Salix. Vol. 7:Magnoliophyta: Salicaceae to Brassicaceae 23–51 (Oxford University Press, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- Fang Z., Zhao S. & Skvortsov A. K. Salicaceae. Vol. 4 139–274 (Science Press & Missouri Botanical Garden Press, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Tao J. & Zhang C. Early Cretaceous angiosperms of the Yanji basin, Jilin provence. Acta Botanica Sinica 32, 220–229 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D. W. Paleobiogeographic Relationships of Angiosperms from the Cretaceous and Early Tertiary of the North American Area. Botanical Review 56, 279–417, doi: 10.1007/BF02995927 (1990). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collinson M. E. The early fossil history of Salicaceae: a brief review. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Section B: Biological Sciences 98, 155–167, doi: doi: 10.1017/S0269727000007521 (1992). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J., Wang Z. & Tang Z. Atlas of woody plants in China: distribution and climate. Vol. 1 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- Hijmans R. J. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. International journal of climatology 25, 1965–1978, doi: 10.1002/joc.1276 (2005). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Obrien E. M. Water‐energy dynamics, climate, and prediction of woody plant species richness: an interim general model. Journal of Biogeography 25, 379–398, doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2699.1998.252166.x (1998). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trabucco A. & Zomer R. J. Global Aridity Index (Global-Aridity) and Global Potential Evapo-Transpiration (Global-PET) Geospatial Database. CGIAR Consortium for Spatial Information. Online database: http://www.cgiar-csi.org/data/global-aridity-and-pet-database (2009).

- Trabucco A. & Zomer R. J. Global Soil Water Balance Geospatial Database. CGIAR Consortium for Spatial Information. Online database: http://www.cgiar-csi.org/data/global-high-resolution-soil-water-b alance (2010).

- U.S. Geological Survey. Global 30 Arc-second Elevation (GTOPO30) https://lta.cr.usgs.gov/GTOPO30 (The last date of access January 2015) (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Center U. N. E. P. w. C. M. Moutians and mountain forests. (World Conservation Monitoring Centre, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- Qian H., Kissling D., Wang X. & Andrews P. Effects of woody plant species richness on mammal species richness in southern Africa. Journal of Biogeography, 36, 1685–1697, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02128.x (2009). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dutilleul P., Clifford P., Richardson S. & Hemon D. Modifying the t Test for Assessing the Correlation Between Two Spatial Processes. Biometrics 49, 305–314, doi: 10.2307/2532625 (1993). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Legendre P. & Anderson M. J. Distance-Based Redundancy Analysis: Testing Multispecies Responses in Multifactorial Ecological Experiments. Ecological Monographs 69, 1–24, doi: 10.2307/2657192 (1999). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magurran A. Measuring Biological Diversity., (Blackwell, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- Kreft H. & Jetz W. Global patterns and determinants of vascular plant diversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104, 5925–5930, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608361104 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Z., Wang Z., Zheng C. & Fang J. Biodiversity in China’s mountains. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 4, 347–352, doi: 10.1890/1540-9295(2006)004[0347;BICM]2.0.CO;2 (2008). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Svenning J.-C. & Skov F. The relative roles of environment and history as controls of tree species composition and richness in Europe. Journal of Biogeography 32, 1019–1033, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01219.x (2005). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blonder B. et al. Linking environmental filtering and disequilibrium to biogeography with a community climate framework. Ecology 96, 972–985, doi: 10.1890/14-0589.1 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myklestad A. & Birks H. J. B. A numerical analysis of the distribution patterns of Salix l. species in Europe. Journal of Biogeography 20, 1–32, doi: 10.2307/2845736 (1993). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Myklesta. The Distribution of Salix Species in Fennoscandia: A Numerical Analysis. Ecography 16, 329–344, doi: 10.111/j.1600-0587.1993.tb00222.x (1993). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tao J. The evolution of the late Cretaceous-Cenozoic floras in China. (Sceince Press, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- Sakai A. Freezing Resistance in Willows from Different Climates. Ecology 51, 485–491, doi: 10.2307/1935383 (1970). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai A., Paton D. M. & Wardle P. Freezing Resistance of Trees of the South Temperate Zone, Especially Subalpine Species of Australasia. Ecology 62, 563–570, doi: 10.2307/1937722 (1981). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai A. & Weiser C. J. Freezing Resistance of Trees in North America with Reference to Tree Regions. Ecology 54, 118–126, doi: 10.2307/1934380 (1973). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savage J. A. & Cavenderbares J. Phenological cues drive an apparent trade-off between freezing tolerance and growth in the family Salicaceae. Ecology 94, 1708–1717, doi: 10.1890/12-1779.1 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X. & Wang X. Recolonization and radiation in Larix (Pinaceae): evidence from nuclear ribosomal DNA paralogues. Molecular Ecology 13, 3115–3123, doi: 10.111/j.1365-294X.2004.02299.x (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne R. I., Davies C., Prickett R., Inns L. & Chamberlain D. F. Phylogeny of Rhododendron subgenus Hymenanthes based on chloroplast DNA markers: between-lineage hybridisation during adaptive radiation? Plant Systematics and Evolution 285, 233–244, doi: 10.1007/s00606-010-0269-2 (2010). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willis K. J. & van Andel T. H. Trees or no trees? The environments of central and eastern Europe during the Last Glaciation. Quaternary Science Reviews 23, 2369–2387, doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2004.06.002 (2004). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maliouchenko O., Palmé A. E., Buonamici A., Vendramin G. G. & Lascoux M. Comparative phylogeography and population structure of European Betula species, with particular focus on B. pendula and B. pubescens. Journal of Biogeography 34, 1601–1610, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2007.01729.x (2007). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seiwa K. et al. Roles of cottony hairs in directed seed dispersal in riparian willows. Plant Ecol 198, 27–35, doi: 10.1007/s11258-007-9382-x (2007). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Normand S. et al. Postglacial migration supplements climate in determining plant species ranges in Europe. Proceedings of The Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 278, 3644–3653, doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.2769 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker L. B., Garfinkee H. L. & Edwards M. E. A late Wisconsin and Holocene vegetation history from the central brooks range: Implications for Alaskan palaeoecology. Quaternary Research 20, 194–214, doi: 10.1016/0033-5894(83)90077-7 (1983). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow N. H. et al. Climate change and Arctic ecosystems: 1. Vegetation changes north of 55°N between the last glacial maximum, mid-Holocene, and present. Journal of Geophysical Research 108, 8170, doi: 10.1029/2002JD002558 (2003). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub M. N. & Schimel J. P. Nitrogen Cycling and the Spread of Shrubs Control Changes in the Carbon Balance of Arctic Tundra Ecosystems. BioScience 55, 408–415, doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2005)055[0408:NCATSO]2.0.CO;2 (2005). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Myerssmith I. et al. Shrub expansion in tundra ecosystems: dynamics, impacts and research priorities. Environmental Research Letters 6, 45509, doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/6/4/045509 (2011). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savage J. A. & Cavenderbares J. Contrasting drought survival strategies of sympatric willows (genus: Salix): consequences for coexistence and habitat specialization. Tree Physiology 31, 604–614, doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpr056 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maschinski J. Impacts of ungulate herbivores on a rare willow at the southern edge of its range. Biological Conservation 101, 119–130, 10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00029-5 (2001). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.