Abstract

Mutations in Angiogenin (ANG), a member of the Ribonuclease A superfamily (also known as RNase 5) are known to be associated with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS, motor neurone disease) (sporadic and familial) and Parkinson’s Disease (PD). In our previous studies we have shown that ANG is expressed in neurons during neuro-ectodermal differentiation, and that it has both neurotrophic and neuroprotective functions. In addition, in an extensive study on selective ANG-ALS variants we correlated the structural changes to the effects on neuronal survival and the ability to induce stress granules in neuronal cell lines. Furthermore, we have established that ANG-ALS variants which affect the structure of the catalytic site and either decrease or increase the RNase activity affect neuronal survival. Neuronal cell lines expressing the ANG-ALS variants also lack the ability to form stress granules. Here, we report a detailed experimental structural study on eleven new ANG-PD/ALS variants which will have implications in understanding the molecular basis underlying their role in PD and ALS.

Angiogenin (ANG), a 14-kDa basic protein is an angiogenic ribonuclease and member of the bovine pancreatic ribonuclease (RNase A) family (also known as RNase 5)1,2,3. Like RNase A, ANG cleaves preferentially on the 3′ side of pyrimidines and follows a transphosphorylation/hydrolysis mechanism4,5. In addition, the crystal structure of human ANG has revealed that it has an RNase A fold and the catalytic triad (residues H13, K40 and H114) is conserved (Fig. 1)6,7,8. The enzymatic activity of ANG is several orders of magnitude lower than that of RNase A towards conventional RNase substrates5, but essential for its angiogenic effect3,9.

Figure 1. Structure of ANG with ALS/PD variants marked.

The active site residues (H13, K40, H114) and the nuclear localization sequence (R31, R32, R33) are shown and are labelled in black along with the N- and C-termini. The disulphide bridges are also shown. K40 and R31 both show multiple conformations. Helices are labelled in dark green and strands in pink. Figures were created using the program PyMOL (http://www.delanoscientific.com)

The mechanism of ANG action is not yet fully understood, but appears to involve different pathways, including receptor binding on endothelial cells10, nuclear transport11,12 and possible activation of proteolytic enzymes and cascades13. It is now established that ANG plays important roles in various physiological and pathological processes. For a recent comprehensive review on ANG, see Sheng and Xu14. In a recent report it has also been shown that ANG can promote hematopoietic regeneration by dichotomously regulating quiescence of stem and progenitor cells15.

Apart from ANG’s role in neovascularization, ANG has been shown to be a neurotropic and neuroprotective factor16,17 and ANG variants have been implicated in ALS and Parkinson’s disease. Greenway et al.18,19 reported that mutations in ANG in ALS, both familial and sporadic. Since these first reports, several other studies worldwide have also identified ANG mutations in ALS patients20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29. Furthermore, a large multi-site study reported the association of mutations in ANG with ALS as well as Parkinson’s disease (PD)21,30,31 (Table 1). In parallel, ANG has also been shown to have a neuroprotective effect in a mouse model of PD32,33.

Table 1. Reported ANG mutations implicated in PD and ALS.

| Human ANG PD/ALS variant | Country of origin | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Signal peptide | ||

| M(−24)I | Italian | 27,28 |

| F(−13)L | German | 25 |

| F(−13)S | Italian | 27,28 |

| V(−12)A | European, North American | 21 |

| G(−10)D | Dutch | 21 |

| G(−8)D | European, North American | 21 |

| P(−4)S | North American | 27,29 |

| P(−4)Q | Belgian | 21 |

| A(−1)P | North American | 30 |

| Mature protein | ||

| Q12L | Irish, Scottish | 18 |

| H13R* | European, North American | 21 |

| K17E | Irish, Swedish | 18 |

| K17I | Irish, Scottish, Northern American, Dutch, German, Belgian | 18,21,23,30 |

| D22V | European, North American | 21 |

| S28N | Northern American | 29 |

| R31K | Irish, English | 18 |

| C39W | European | 18 |

| K40I | Irish, Scottish | 18,19 |

| K40R* | European, North American | 21 |

| I46V | Scottish, Italian, French, German, Swedish | 18,21,25, 26, 27, 28 |

| K54E | German | 25 |

| K54R* | European, North American | 21 |

| K60E* | North American | 30 |

| Q77P* | North American | 30 |

| T80S* | Dutch | 21 |

| R95Q* | European, North American | 21 |

| F100I* | Dutch | 21 |

| P112L | Northern American | 29 |

| V103I* | Chinese | 20 |

| V113I | Italian | 27 |

| H114R* | Italian | 27 |

| R121C* | Italian | 21,22 |

| R121H | French | 26 |

Colour codes: ANG-ALS variants, ANG-PD variants (bold), ANG- implicated in both ALS and PD variants (bold-italic).

*Crystal structures of ANG-ALS variants presented in this report.

In italics- Crystal structures of ANG-ALS variants presented in a previous report by Thiyagarajan et al.8.

While human ANG is also shown to be upregulated especially in prostate cancers and glioblastomas34, it is downregulated in ALS and PD35. At the cellular level, it has also been established that, in response to growth stimuli, ANG undergoes nuclear translocation and stimulates ribosomal RNA (rRNA) transcription, which is essential for cell growth and proliferation36. Further findings established that ANG is a stress-activated RNase that cleaves tRNA fragments which can inhibit translation initiation and is a key to stress response and cell survival37,38,39,40. Thus, it is quite likely that excessive ANG action underlies uncontrolled cell proliferation and sustained growth as manifested in cancer whereas its insufficiency might be a pathogenesis of degenerative diseases which are characterized as decreased survival and premature death35.

In order to elucidate the role of ANG mutations in ALS, we have shown previously that some ANG variants have significant reduction in RNase activity which is correlated with a reduction in cell proliferation and angiogenic activities41. These results formed the basis for understanding the role of ANG in ALS and neuronal differentiation and a definitive role for ANG in neurite growth and pathfinding was established16. We have also shown that ANG is a neuroprotective factor and ALS-associated ANG variants affect neurite extension/pathfinding and survival of motor neurons17. In a more recent comprehensive study we have provided (for the first time) detailed structural and molecular insights into the mechanism of action of eleven human ANG-ALS variants in neurons8. In this report, we have extended our structural study to eleven new human ANG PD/ALS variants and provide the detailed molecular features of these variants in comparison with the normal ANG protein, thus progressing from understanding structure to using structure to understanding disease.

Results and Discussion

We have determined the crystal structure of eleven ANG-PD/ALS variants H13R, K40R, K54R, K60E, Q77P, T80S, R95Q, F100I, V103I, H114R, R121C (Table 2, in the resolution range 2.3–1.35 Å) and elucidated the structural changes in the key functional regions of the variants by comparing them with the high resolution structure of native (wild-type) ANG (reported previously by us at 1.04 Å)8, (Tables 3 and 4). We have also assessed the catalytic (RNase) activity (i.e., activity toward tRNA) of ANG PD/ALS variants which showed diminished level of RNase activity, in the range of 0.0–80% compared with the native ANG protein except variant R121C which showed enhanced activity of 131% (Table 4).

Table 2. Crystallographic data for ANG PD/ALS variants.

| Variant | H13R | K40R | K54R | K60E | Q77P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crystallisation conditions | 0.2 M Na/K tartrate 20% PEG 3350 | 0.4 M Na/K tartrate 0.1 M Na citrate, pH 5.5 20% PEG 4000 | 0.2 M Na/K tartrate 0.1 M HEPES, pH 7.0 3% Propanol 20% PEG 8000 | 0.2 M Na/K tartrate 0.1 M Na cacodylate, pH 6.5 25% PEG 4000 | 0.2 M ammonium sulphate 0.1 M Bis-tris, pH 5.5 25% PEG 3350 | |

| Space group | P21212 | C2221 | C2221 | C2221 | P1 | |

| Cell dimensions (a, b, c in Å, α, β, γ, in °) | 37.4, 85.8, 32.9, 90, 90, 90 | 82.8, 116.1, 37.4, 90, 90, 90 | 82.9, 118.8, 37.1, 90, 90, 90 | 83.1, 117.1, 37.3, 90, 90, 90 | 50.2, 50.3, 62.2, 103.4, 103.6, 110.4 | |

| No. molecules in ASU | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 42.8–1.94 | 58.0–2.05 | 32.5–2.28 | 58.5–1.90 | 56.8–1.65 | |

| *Rmerge | 0.193 (1.938) | 0.066 (0.359) | 0.127 (0.846) | 0.059 (0.542) | 0.263 (1.760) | |

| Rmeas | 0.244 (2.526) | 0.077 (0.496) | 0.152 (1.019) | 0.075 (0.679) | 0.281 (1.933) | |

| Rpim | 0.149 (1.604) | 0.038 (0.340) | 0.058 (0.400) | 0.034 (0.314) | 0.099 (0.777) | |

| CC1/2 | 0.986 (0.466) | 0.998 (0.887) | 0.994 (0.904) | 0.992 (0.626) | 0.988 (0.622) | |

| Mean < I/σI> | 4.9 (1.2) | 15.0 (2.5) | 6.7 (1.1) | 14.2 (2.6) | 7.3 (1.9) | |

| Completeness | 99.2 (91.2) | 95.4 (69.6) | 100.0 (100.0) | 96.2 (71.2) | 96.6 (70.4) | |

| Total number of reflections | 34867 (1963) | 71536 (1702) | 51806 (5108) | 67772 (3096) | 898984 (25028) | |

| Unique reflections | 8160 (493) | 11150 (616) | 8730 (842) | 14137 (684) | 60548 (2326) | |

| Multiplicity | 4.3 (4.0) | 6.4 (2.8) | 5.9 (6.1) | 4.8 (4.5) | 14.8 (10.8) | |

| Refinement statistics | ||||||

| Rwork/Rfree | 23.2/29.7 | 18.5/23.0 | 22.0/27.1 | 17.8/21.6 | 23.2/27.1 | |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | ||||||

| Protein | 30.9 | 36.6 | 48.2 | 30.9 | 22.3 | |

| Solvent | 33.8 | 44.7 | 42.1 | 39.5 | 28.8 | |

| Ligand | 51.3 | 54.1 | 65.2 | 35.9 | 52.7 | |

| Number of atoms | ||||||

| Protein | 955 | 1022 | 998 | 1034 | 3941 | |

| Solvent | 30 | 72 | 32 | 99 | 330 | |

| Ligand | 10 | 17 | 17 | 10 | 107 | |

| RMSD | ||||||

| bond length (Å) | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.011 | 0.010 | 0.012 | |

| bond angle (°) | 1.41 | 1.42 | 1.52 | 1.31 | 1.50 | |

| Ramachandran statistics (%) | ||||||

| Favoured | 96.5 | 95.4 | 96.4 | 98.1 | 93.9 | |

| Allowed | 2.6 | 4.6 | 3.6 | 1.9 | 5.7 | |

| Outliers | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | |

| **Ligands | TAR | TAR, PEG | TAR, PEG | TLA | SO4, PGE, EDO, BTB | |

| PDB code | 5M9A | 5M9C | 5M9G | 5M9J | 5M9M | |

| Variant | T80S | R95Q | F100I | V103I | H114R | R121C |

| Crystallisation conditions | 0.2 M ammonium sulphate 0.1 M Bis-tris propane, pH 5.5 25% PEG 3350 | 0.2 M ammonium sulphate 0.1 M Na cacodylate, pH 6.5 30% PEG 8000 | 0.2 M Na/K tartrate 0.1 M Na cacodylate, pH 6.5 20% PEG 4000 | 0.2 M Na/K tartrate 0.1 M MES, pH 6.5 20% PEG 4000 | 0.01 M Na borate, pH 8.51.1 M Na citrate | 0.2 M Na/K tartrate 0.1 M Bis-tris propane, pH 6.5 16% PEG 4000 |

| Space group | P21212 | P21212 | P1 | C2221 | P3221 | C2221 |

| Cell dimensions (a, b, c in Å, α, β, γ, in °) | 82.4, 37.3, 42.8, 90, 90, 90 | 82.6, 37.4, 43.1, 90, 90, 90 | 30.9, 34.8, 52.9, 89.7, 84.2, 84.3 | 82.8, 115.9, 37.3, 90, 90, 90 | 81.4, 81.4, 86.0, 90, 90, 120 | 82.5, 119.0, 37.4, 90, 90, 90 |

| No. molecules in ASU | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 42.8–1.80 | 82.6–1.35 | 52.7–1.44 | 67.4–1.85 | 70.5–2.20 | 67.8–1.70 |

| *Rmerge | 0.135 (0.528) | 0.105 (1.394) | 0.096 (0.171) | 0.199 (0.994) | 0.110 (0.712) | 0.097 (1.752) |

| Rmeas | 0.156 (0.662) | 0.144 (1.613) | 0.136 (0.242) | 0.226 (1.324) | 0.121 (0.913) | 0.120 (2.190) |

| Rpim | 0.057 (0.342) | 0.031 (0.595) | 0.096 (0.171) | 0.076 (0.723) | 0.036 (0.436) | 0.070 (1.300) |

| CC1/2 | 0.984 (0.650) | 0.998 (0.434) | 0.989 (0.937) | 0.993 (0.461) | 0.994 (0.681) | 0.997 (0.470) |

| Mean < I/σI> | 9.0 (2.0) | 11.1 (1.5) | 6.5 (3.9) | 6.3 (1.0) | 12.1 (1.8) | 7.3 (0.9) |

| Completeness | 95.7 (77.9) | 96.6 (71.6) | 95.1 (80.1) | 90.7 (76.3) | 95.8 (75.9) | 99.7 (98.6) |

| Total number of reflections | 77958 (1844) | 348247 (7220) | 91164 (3685) | 91131 (1991) | 156743 (3932) | 106361 (5445) |

| Unique reflections | 12236 (596) | 29013 (1033) | 37557 (1635) | 14125 (723) | 16435 (1101) | 20751 (1063) |

| Multiplicity | 6.4 (3.1) | 12.0 (7.0) | 2.4 (2.3) | 6.5 (2.8) | 9.5 (3.6) | 5.1 (5.1) |

| Refinement statistics | ||||||

| Rwork/Rfree | 23.9/28.5 | 15.1/17.9 | 17.2/19.5 | 20.8/26.5 | 18.2/23.6 | 20.9/23.9 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | ||||||

| Protein | 21.3 | 18.4 | 12.1 | 33.1 | 49.9 | 31.7 |

| Solvent | 28.5 | 33.1 | 23.4 | 39.1 | 47.7 | 41.0 |

| Ligand | 54.9 | 40.7 | 14.3 | 54.0 | 66.5 | 36.4 |

| Number of atoms | ||||||

| Protein | 1020 | 1071 | 1989 | 1010 | 1986 | 1026 |

| Solvent | 73 | 154 | 236 | 67 | 67 | 110 |

| Ligand | 20 | 51 | 47 | 10 | 11 | 10 |

| RMSD | ||||||

| bond length (Å) | 0.011 | 0.013 | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.011 |

| bond angle (°) | 1.46 | 1.75 | 1.62 | 1.49 | 1.60 | 1.37 |

| Ramachandran statistics (%) | ||||||

| Favoured | 98.1 | 97.1 | 95.6 | 97.3 | 96.2 | 96.3 |

| Allowed | 1.9 | 2.9 | 3.9 | 2.7 | 3.4 | 3.7 |

| Outliers | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.4 | 0 |

| **Ligands | SO4 | SO4, PEG, PGE | TAR, TLA, PEG | TAR | GOL, BO4 | TLA, CYS |

| PDB code | 5M9P | 5M9Q | 5M9R | 5M9S | 5M9T | 5M9V |

*Values in parentheses refer to the highest resolution shell.

**Ligand definition based on observation in the electron density maps from each variant structure: TAR, D-tartrate; PEG, di-ethylene glycol; TLA, L-tartrate; SO4, sulphate ion; PGE, tri-ethylene glycol; EDO, ethylene glycol; BTB, bis-tris methane; GOL, glycerol; BO4, borate ion; CYS, cysteine (glutathione linked).

Table 3. Hydrogen bond and van der Waals contact residues in ANG and ANG-PD and ANG-ALS variants.

| Variant | Potential hydrogen bonding residues |

Potential van der Waals contact residues |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retained | Gained | Lost | Retained | Gained | Lost | |

| H13R | F9, I46 | N43, Q117 | T44 | F9, L10, T11, K40, T44, F45, I46, L115, Q117 | ||

| K40R | L35, P38, Y94 | Q12 | I42, N43 | M30, P38, I42, N43, Y94 | Q12, L35 | H13 |

| K54R | K50, I56, C57 | Y6 | R51, S52, I56, C57, L111, P112 | Y6, K50 | ||

| K60E | E58 | A55, G62, K73 | E58 | |||

| Q77P | H47 | R21 | I46, H47, G99, F100 | R21 | ||

| T80S | T44, T97 | C26, N43, R95, A96, T97, F120 | I42, T44, K82 | |||

| R95Q | K82 | D23, C81, K82, T97 | H84 | |||

| F100I | S75, F76, Q77 | |||||

| V103I | S72 | R70, I71, V78, V105, I119, F120 | I46, I56, F76 | |||

| H114R | A106 | F9, V105, A106 | L69 | D116 | ||

| R121C | S118, I119, F120 | |||||

*Note- The electron density for R121C is not optimal while R122 shows poor density and P123 is not visible in the electron density map (i.e., disordered) in the R121C variant structure. Also, the cysteine residue with a glutathione molecule bound to the free cysteine was observed in the variant structure.

Table 4. Structural deviation and solvent accessibility changes caused by ANG PD and ALS variants.

| ANG ALS/PD variant | (% RNase activity) | Solvent accessibility area of corresponding residue in ANG PD/ALS variant (Å2) | Solvent accessibility area of corresponding residue in Native ANG (Å2) | Root-mean-square deviation against native ANG** (Å) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H13R | 0.0 | 22.7 | 9.7 | 0.27 |

| 2 | K40R | 6.3 | 79.9 | 56.8 | 0.19 |

| 3 | K54R | 48.5 | 85.7 | 81.1 | 0.26 |

| 4 | K60E | 79.6 | 135.0 | 153.9 | 0.17 |

| 5 | Q77P | 60.1 | 39.0 | 78.2 | 0.49 |

| 6 | T80S | 78.7 | 8.5 | 0.0 | 0.23 |

| 7 | R95Q | 52.0 | 123.5 | 131.6 | 0.18 |

| 8 | F100I | 39.1 | 109.7 | 104.5 | 0.31 |

| 9 | V103I | 54.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.25 |

| 10 | H114R | 1.6 | 127.0 | 87.0 | 0.44 |

| 11 | R121C | 131.2 | 58.1 | 140.9 | 0.20 |

*Percentage RNase activity to yeast tRNA in comparison to the native ANG Met−1 ANG (100%).

**Against PDB-4AOH native ANG structure by Thiyagarajan et al.8.

As reported previously, the active site of ANG consists of several sub-sites (as originally described for RNase A): a P1 substrate binding site involved in phosphodiester bond cleavage; a B1 site for binding the pyrimidine whose ribose donates its 3′ oxygen to the scissile bond; a B2 site that preferentially binds a purine ring on the opposite side of the scissile bond; and additional sites for peripheral bases and phosphates6.

ANG residues H13, K40 and H114 (part of the P1 sub-site) correspond to the catalytic triad. Replacements of H13 or H114 by Ala3 or K40 by Gln9 decrease ribonucleolytic activity by factors of at least 104, 104 and 2 × 103, respectively. These early findings established that the roles of the three ANG residues are similar to those of their counterparts in RNase A.

In the crystal structure of H13R ANG PD variant, the substitution of H13 by Arg is very clear in the electron density map and the overall structure is largely the same as with native ANG. In the native structure, Nδ1 of H13 forms a hydrogen bond with the main-chain O of T44 and Nε2 makes a water-mediated interaction with the amide nitrogen atom of L115 (Table 3). In the variant, the Arg side chain stretches out into the active site pocket making a direct interaction with Q117 while retaining its interactions with residues T44 and L115 (Fig. 2). The interaction with Q117 (known to be the obstructive pyrimidine-binding site residue in ANG)6,42 seem to result with slight rearrangement of the C-terminal helix. In addition, in the variant, the Arg side chain is not optimally positioned to interact with the two other catalytically important residues K40 and H114. This provides a structural explanation for the dramatic loss of RNase activity observed in this variant.

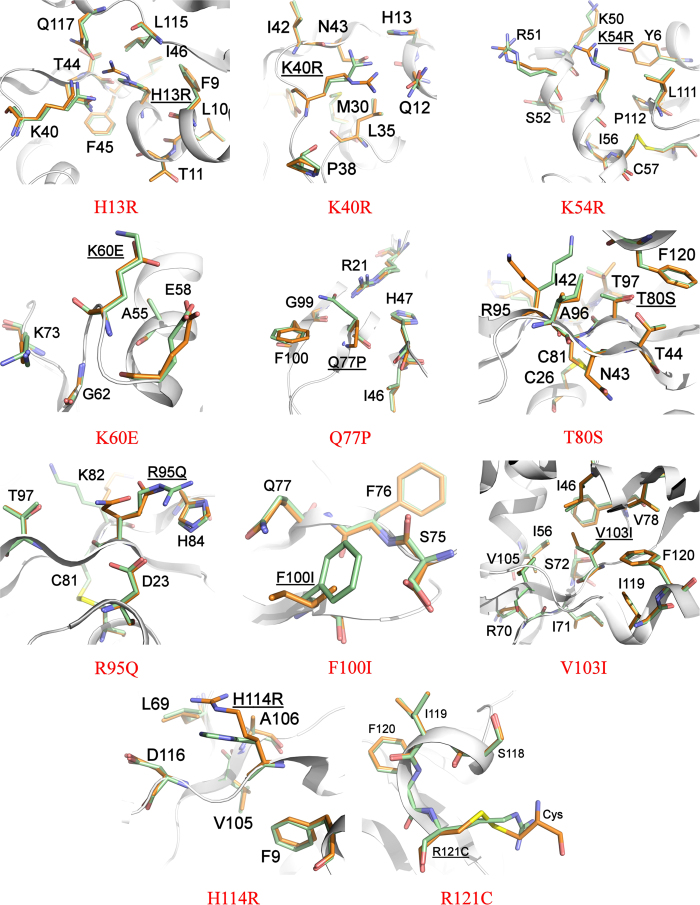

Figure 2. Structural comparison of ANG and ALS/PD-associated variants.

Superposition of native ANG (in green) and ANG-ALS/PD variants (in orange). Residues that exhibit hydrogen bonding or Van der Waals contacts with the ANG-ALS/PD residues in either native ANG or mutant structures are also shown. The variant residues are underlined. The cysteine from the glutathione bound to R121C variant is also shown.

K40 is a key residue at the catalytic centre of ANG and adopts multiple conformation in the native structure. However the conservative substitution of Arg for K40 reduces the activity to ~6%, similar to the effect of the K41 to Arg mutation in RNase A43. In the crystal structure of the ALS variant K40R, the Arg side chain possesses a single conformation and several key interactions of K40 (with residues Q12, C39, N43 and T44, which are integral to the catalytic site) known to be important for the stabilization of the pentavalent transition state during RNA cleavage are lost (Table 4, Fig. 2). Instead, in the variant, the Arg side-chain makes direct interaction with Q112 by reorienting its side chain (more solvent exposed, Table 4).

In the H114R ALS variant the protein retains only 2% of the enzymatic activity toward tRNA. H114 is part of the catalytic site (P1) in the native structure and makes direct interaction with D116. However, in the variant structure (Fig. 2) this interaction is lost and a new van der Waals interaction with L69 has been observed involving the flexible loop region H65-R70. The main chain of R114 also makes an interaction with Q12 (which is known to be part of the substrate-binding site in the native protein). The loss of interaction with D116 also results with movement of C-terminal residues beyond D116 thus causing destablization in the variant structure (where the Arg side chain is more solvent exposed compared with the His residue in the native structure, Table 4) which will have major impact on the loss of catalytic activity as these residues are implicated in substrate recognition.

K54 does not participate or belong to any of the known catalytic sub-sites of ANG6. The variant K54R retains ~49% of enzyme activity (Table 4). In this PD variant structure this residue is exposed on the surface of the molecule. As described previously in the case of K54E ALS variant structure8, it is likely that the basic nature of the mutated residue in the variant will have an influence on the catalytic activity through a new interaction with residue Y6 (Fig. 2) and a slight rearrangement of the N-terminal helix involving the catalytically important residue H13. Also, in the variant structure the Arg side chain makes a water mediated interaction with R51.

ANG residues 60–68 are part of an external region that includes strand B2 and loops on either side (Fig. 1)6. Based on known experimental data to date this region has been predicted to form part of the cell receptor binding site44. K60 forms part of this region at one end of the segment and is located on the surface of the molecule in the 3D structure. Mutation of the residue to Glu retains ~80% of the enzymatic activity. Previously it has been shown that chemical modification of K60 retained 34% activity9 and this surface residue has minor catalytic role. In the K60E PD variant structure the mutated residue gains a new interaction with E58 (Fig. 2), which seems to result in a level of repulsion of neighbouring residues in comparison to the wild-type ANG structure.

The residue Q77 forms part of the β4 strand in the ANG wild-type structure. So far there is no assigned role for this residue. However, in the Q77P PD variant structure (which contains 4 molecules in the asymmetric unit with clear electron density for the proline ring, which is less accessible to solvent) the hydrogen-bond (2.9 Å) observed between Q77 and R21 (part of helix α2) is lost (Fig. 2) thus creating a hydrophobic environment. However, in the variant structure, residue P77 also retains van der Waals contacts with residues I46 and F100 that are in close proximity to the substrate binding site (Table 3). However, these structural changes might contribute for the loss (~40%) of enzyme activity (Table 4).

In the native ANG structure, a hydrogen bond links the Oγ1 atoms of T44 and T806. In addition, based on mutagenesis and structural studies it was proposed previously that the strong cytidine preference of T80A is attributable to the intrinsic ability of T44 to form a much more effective hydrogen bond with N3 of cytidine than with that of uridine nucleotides45,46. Thus in native ANG, the T44-T80 hydrogen bond selectively weakens the interaction between T44 and N3 of cytosine. In the T80S ALS variant structure, the position of S80 is well defined in the electron density map and its atoms occupy positions essentially the same as in those of the corresponding atoms in native ANG. In particular, the position of Oγ1 atom of T80 overlaps with the equivalent position of Oγ atom of S80 in the variant structure (more solvent accessible, Table 4) and retains most of the interactions seen in the wild-type structure. However, a significant number of van der Waals contacts surrounding residue T44 are lost in the variant structure. In addition, the absence of Cγ2 atom in the variant structure meant that most of the van der Waals hydrophobic interactions with I42 are lost as well. It is quite likely that this results in slight reduction in stability, causing the observed loss in catalytic activity (~22%, Table 4, Fig. 2).

R95 is located on the surface of the molecule in the structure of ANG. It forms part of the β5 strand and interacts with K82 and H84 from the neighboring β4 strand6. Based on previous mutagenesis studies, both K82 and H84 have been shown to have minor roles in catalysis. In the PD variant structure R95Q (Fig. 2), the Gln side chain is flexible (can be observed in two possible conformations in the electron density map). However, shortening of the side chain length in the variant seems to have resulted with loss of interactions with H84 thus providing a possible explanation for the diminished catalytic activity of 52% (Table 4).

In the native ANG structure F100 and V103 residues (located on β5 and β6 strands respectively, Fig. 1) are in close proximity to the substrate binding site involving residue E108. The results from two variant structures F100I and V103I are analyzed here and both the variant residues are well defined in their respective electron density maps. The F100I variant implicated in ALS has retained only 39% of the enzymatic activity due to the significant loss of main chain interactions with S75 even though several of the side chain interactions have been retained with S75 (Fig. 2). The introduction of an Ile residue seems to have slightly increased flexibility in the vicinity of the mutated residue. On the other hand, in the V103I ALS variant structure, the side chain seems to have gained additional interactions with residues I46, I56 and F76 making the hydrophobic core more stable (Fig. 2). This provides some structural explanation for the altered catalytic activity for this variant.

An important structural feature of ANG is that a part of the active site (i.e., the C-terminal region of the molecule) is obstructed by residue Q117 (part of the pyrimidine recognition site)6. It has been postulated that movement of Q117 and adjacent residues is required for substrate binding and catalysis42. Mutational studies on C-terminal segment of ANG have also shown that shorter side-chain residues or deletion of residues affects the catalytic activity47 and previous structural studies have revealed that the segment containing residues 117–123 in the wild-type is highly mobile48. In the 3D structure of native ANG, R121 forms part of a peripheral sub-site for binding polynucleotide substrates at the C-terminal region’s closed conformation. The ALS associated variant R121C has significantly higher RNase activity (131%) as compared with wild-type ANG. In the crystal structure of the variant (Fig. 2), the smaller side-chain of cysteine appears to provide more flexibility for the C-terminal end of the molecule by destabilizing the closed conformation thus providing better access to substrates which would explain the enhanced RNase activity. Similar observations have been reported previously for the R121H ALS implicated variant8.

In summary, we have elucidated altered molecular interactions that underpin the abrogated catalytic efficiency or an increase in RNase activity (directly linked to ANG function) of eleven new variants of ANG implicated in PD and ALS using high resolution X-ray diffraction data. In our previous studies6,16,17 we have shown that the survival of the motor neurons and neurite extension are linked to the weak RNase activity. Abrogation of the RNase activity or an increase in RNase activity both have phenotypic consequences on the motor neurons leading to fragmented neurites in ALS settings. It is quite likely that similar effects could be anticipated in the case of PD setting which need further experimental study using ‘in vitro’ model systems. Meanwhile the observations made from the present study will provide the structural basis in understanding the biological roles for these variants which have been implicated in PD and ALS.

Methods

Expression and purification of native and ANG-PD/ALS variants

Wild-type and all ANG PD/ALS variants were prepared as reported in Holloway et al.49. Briefly, a synthetic gene for wild-type ANG with E. coli codon bias was inserted into pET-22b(+)(Novagen) for expression of the Met-(−1) form of the protein. The QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis method was used to introduce mutations. After DNA sequencing (Cogenics, UK; MWG, Germany) to confirm the presence of the mutations, mutant plasmids were used to transform E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. Bacterial cells were grown in Terrific Broth at 37 °C to an OD600 of 0.5–0.6, after which expression was induced by addition of isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 1 mM and incubation was continued for ~3 hours before harvesting. The target proteins from inclusion bodies were extracted, refolded and purified by SP-Sepharose chromatography followed by C4 reversed-phase HPLC49. Purified proteins were lyophilized and dissolved in HPLC grade water. All ANG variants behaved similarly to the wild-type protein during purification. Concentrations of all recombinant proteins were determined from UV absorbance, using an ε280 value of 12,500 M−1cm−1 calculated by the method described by Pace et al.50 All purified protein masses were experimentally confirmed using the electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry (ESIMS). In the case of R121C variant, the mass spectrometry data showed that an additional glutathione residue was attached to the free cysteine residue.

Ribonucleolytic activity assay

Activity toward tRNA was determined by measuring the formation of acid soluble fragments as described by Shapiro et al.5 Assay mixtures contained 2 mg ml–1 yeast tRNA (Sigma), 0.1 mg ml–1 bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, or 0.5 μM test protein in 33 mM Na-Hepes, 33 mM NaCl, pH 7.0. After 2 h of incubation at 37 °C, reactions were terminated by the addition of 2.3 vol ice-cold 3.4% perchloric acid, the mixtures were centrifuged at 13000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the absorbance of the supernatants were measured at 260 nm (Table 4). Each data point used in the calculation were the mean of 3 measurements. In all cases, the standard deviation is less than 2% of the mean. The activities listed are the means of the values calculated for 0.3, 0.4 and 0.5 μM variant.

X-ray crystallographic studies

Variant ANG proteins were crystallised using the sitting drop method, some conditions were optimised with hanging drop (for detailed conditions used see Table 2). Diffraction data were collected at 100 K, with poly(ethylene glycol) 4000 (30% w/v) or 25% glycerol as a cryoprotectant, on beamlines i02, i03, i04, i04–1 and i24 at Diamond Light Source (Oxon, UK) equipped with ADCS Quantum 315 and Dectris PILATUS detectors (Dectris, Switzerland). CCD data and some PAD datasets were indexed and integrated with Xia251,52 pipeline 3dii using XDS53 while the remaining PAD data were indexed and integrated with DIALS54. Higher multiplicity X-ray diffraction data were collected for more recent datasets to maximise the resolution of the data. Some datasets have higher values for Rmerge or statistics derived from Rmerge than might traditionally be accepted due to poorer quality diffraction or higher multiplicity, however, as resolution cut-offs based on data quality were selected to achieve a minimum CC1/2 of 0.455,56, these statistics were deemed acceptable. Resolution cut-offs were also selected based on a minimum outer shell completeness of approximately 70%. All data were scaled with AIMLESS56,57. Space group assignments were confirmed with ZANUDA58.

Initial phases were obtained by molecular replacement with PHASER59 using 1ANG as the starting model6. Further refinement and model building were carried out with REFMAC560 and COOT61, respectively. Visible bound water and ligand molecules (from the crystallisation medium) were modelled into the electron density using difference density map (Fo-Fc) after all the protein atoms were built. With each data set, a set of reflections (between 5–10%) was kept aside for the calculation of Rfree. All the structures were validated using MolProbity validation tool62. There were no residues in the disallowed region of the Ramachandran plot except <1% in the H13R, Q77P, F100I and H114R variant structures. Crystallographic data statistics are summarized in Table 2. All figures were rendered and RMSDs between 4AOH, the high resolution native ANG structure, and variant structures were calculated using PyMol (DeLano Scientific LLC, San Carlos, CA, USA). Solvent accessibilities were calculated with Areaimol63.

Additional Information

Accession codes: The atomic coordinates and structure factor amplitudes have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank (www.pdb.org) (PDB ID codes for ANG variants are- 5M9A, 5M9C, 5M9G, 5M9J, 5M9M, 5M9P, 5M9Q, 5M9R, 5M9S, 5M9T and 5M9V for H13R, K40R, K54R, K60E, Q77P, T80S, R95Q, F100I, V103I, H114R and R121C respectively).

How to cite this article: Bradshaw, W. J. et al. Structural insights into human angiogenin variants implicated in Parkinson’s disease and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Sci. Rep. 7, 41996; doi: 10.1038/srep41996 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (UK) programme grant (083191) and equipment grant (088464) to K.R.A. The authors would like to thank Diamond Light Source for beamtime (proposals, mx313, mx7131, mx8922 and mx12342) and the staff of beamlines i02, i03, i04, i04-1 and i24 for assistance with crystal testing and data collection.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions W.J.B., S.R., T.T.K.P., N.T. and R.L.L. performed protein expression, purification and structural biology experiments. W.J.B. solved and analysed the structures. V.S. analysed the data and edited the manuscript. K.R.A. supervised the work, analysed the data, wrote and edited the manuscript.

References

- Fett J. W. et al. Isolation and characterization of angiogenin, an angiogenic protein from human carcinoma-cells. Biochemistry 24, 5480–5486 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strydom D. J. et al. Amino acid sequence of human tumor derived angiogenin. Biochemistry 24, 5486–5494 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro R. & Vallee B. L. Site-directed mutagenesis of histidine-13 and histidine-114 of human angiogenin alanine derivatives inhibit angiogenin induced angiogenesis. Biochemistry 28, 7401–7408 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper J. W. & Vallee B. L. A covalent angiogenin/ribonuclease hybrid with a fourth disulfide bind generated by regional mutagenesis. Biochemistry 28, 1875–1884 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro R., Riordan J. F. & Vallee B. L. Characteristic ribonucleolytic activity of human angiogenin. Biochemistry 25, 3527–3532 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acharya K. R., Shapiro R., Allen S. C., Riordan J. F. & Vallee B. L. Crystal structure of human angiogenin reveals the structural basis for its functional divergence from ribonuclease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 2915–2919 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonidas D. D. et al. Refined crystal structures of native human angiogenin and two active site variants: implications for the unique functional properties of an enzyme involved in neovascularisation during tumour growth. J Mol Biol. 285, 1209–1233 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiyagarajan N., Ferguson R., Subramanian V. & Acharya K. R. Structural and molecular insights into the mechanism of action of human angiogenin-ALS variants in neurons. Nat Commun. 3, 1121, doi: 10.1038/ncomms2126 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro R., Fox E. A. & Riordan J. F. Role of lysines in human angiogenin: chemical modification and site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 28, 1726–1732 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G. F., Riordan J. F. & Vallee B. L. A putative angiogenin receptor in angiogenin-responsive human endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94, 2204–2209 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G. F., Xu C. J. & Riordan J. F. Human angiogenin is rapidly translocated to the nucleus of human umbilical vein endothelial cells and binds to DNA. J Cell Biochem. 76, 452–462 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroianu J. & Riordan J. F. Nuclear translocation of angiogenin in proliferating endothelial cells is essential to its angiogenic activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 1677–1681 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G. F., Riordan G. F. & Vallee B. L. Angiogenin promotes invasiveness of cultured endothelial cells by stimulation of cell-associated proteolytic activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91, 12096–12100 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng J. & Xu Z. Three decades of research on angiogenin: a review and perspective. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 1–12, doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmv131 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves K. A. et al. Angiogenin promotes hematopoietic regeneration by dichotomously regulating quiescence of stem and progenitor cells. Cell 166, 1–13 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian V. & Feng Y. A new role for angiogenin in neurite growth and pathfinding-implications for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet 16, 1445–1453 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian V., Crabtree B. & Acharya K. R. Human angiogenin is a neuroprotective factor and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis associated angiogenin variants affect neurite extension/pathfinding and survival of motor neurons. Hum. Mol. Genet 17, 130–149 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenway M. J. et al. Loss-of-function ANG mutations segregate with familial and ‘sporadic’ amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature Genet 38, 411–413 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenway M. J. et al. A novel candidate region for ALS on chromosome 14q11.2. Neurology 63, 1936–1938 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Z.-Y. et al. Identification of a novel missense mutation in angiogenin in a Chinese amyotrophic lateral sclerosis cohort. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 13, 270–275 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Es M. A. et al. Angiogenin variants in Parkinson disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol 70, 964–973 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luigetti M. et al. SOD1 G93D sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (SALS) patient with rapid progression and concomitant novel ANG variant. Neurobiol Aging 32, 1924.e1915-1928 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Es M. A. et al. A case of ALS-FTD in a large FALS pedigree with a K17I ANG mutation. Neurology 72, 287–288 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seilhean D. et al. Accumulation of TDP-43 and alpha-actin in an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patient with the K17I ANG mutation. Acta Neuropathol 118, 561–573 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Santiago R. et al. Identification of novel Angiogenin (ANG) gene missense variants in German patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol 256, 1337–1342 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paubel A. et al. Mutations of the ang gene in French patients with sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch. Neurol 65, 1333–1336 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellera C. et al. Identification of new ang gene mutations in a large cohort of italian patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurogenetics 9, 33–40 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conforti F. L. et al. A novel angiogenin gene mutation in a sporadic patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis from southern Italy. Neuromuscul. Disord 18, 68–70 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D. et al. Angiogenin loss-of-function mutations in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol 62, 609–617 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayaprolu S. et al. Angiogenin variation and Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol 71, 725–727 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. L., Wu R. M., Tai C. H. & Lin C. H. Mutational analysis of angiogenin gene in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One. 9, e112661, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112661 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steidinger T. U., Standaert D. G. & Yacoubian T. A. A neuroprotective role for angiogenin in models of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem 116, 334–341 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steidinger T. U., Slone S. R., Ding H., Standaert D. G. & Yacoubian T. A. Angiogenin in Parkinson disease models: role of Akt phosphorylation and evaluation of AAV-mediated angiogenin expression in MPTP treated mice. PLoS One 8, e56092, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone0056092 (2913). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson K. A., Byers H. R., Key M. E. & Fett J. W. Inhibition of prostate carcinoma establishment and metastatic growth in mice by an anti-angiogenin monoclonal antibody. Int J Cancer. 98, 923–929 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S. & Hu G. F. Emerging role of angiogenin in stress response and cell survival under adverse conditions. J Cell Physiol 227, 2822–2826 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto K., Liu S., Tsuji T., Olson K. A. & Hu G. F. Endogenous angiogenin in endothelial cells is a general requirement for cell proliferation and angiogenesis. Oncogene 24, 445–456 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skorupa A. et al. Motoneurons secrete angiogenin to induce RNA cleavage in astroglia. J Neurosci 32, 5024–5038 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov P., Emara M. M., Villen J., Gygi S. P. & Anderson P. Angiogenin-induced tRNA fragments inhibit translation initiation. Mol Cell 43, 613–623 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emara M. M. et al. Angiogenin-induced tRNA-derived stress-induced RNAs promote stress-induced stress granule assembly. J Biol Chem 285, 10959–10968 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki S., Ivanov P., Hu G. F. & Anderson P. Angiogenin cleaves tRNA and promotes stress-induced translational repression. J Cell Biol 185, 35–42 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree B. et al. Characterization of human angiogenin variants implicated in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochemistry. 46, 11810–11818 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo N., Shapiro R., Acharya K. R., Riordan G. F. & Vallee B. L. Role of glutamine-117 in the ribonucleolytic activity of human angiogenin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91, 2920–2924 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trautwein K., Holliger P., Stackhouse J. & Benner S. A. Site-directed mutagenesis of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease: lysine-41 and aspartate-121. FEBS Lett. 281, 275–277 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallahan T. W., Shapiro R., Strydom D. J. & Vallee B. L. Importance of asparagine-61 and asparagine-109 to the angiogenic activity of human angiogenin. Biochemistry. 31, 8022–8029 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro R. Structural features that determine the enzymatic potency and specificity of human angiogenin: threonine-80 and residues 58–70 and 116–123. Biochemistry 37, 6847–6856 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway D. E. et al. Crystallographic studies on structural features that determine the enzymatic specificity and potency of human angiogenin: Thr44, Thr80, and residues 38-41. Biochemistry. 43, 1230–1241 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo N., Nobile V., Di Donato A., Riordan J. F. & Vallee B. L. The C-terminal region of human angiogenin has a dual role in enzymatic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93, 3243–3247 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonidas D. D., Shapiro R., Subbarao G. V., Russo A. & Acharya K. R. Crystallographic studies on the role of the C-terminal segment of human angiogenin in defining enzymatic potency. Biochemistry. 41, 2552–2562 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway D. E., Hares M. C., Shapiro R., Subramanian V. & Acharya K. R. High-level expression of three members of the murine angiogenin family in Escherichia coli and purification of the recombinant proteins. Protein Expr Purif 22, 307–317 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace C. N., Vajdos F., Fee L., Grimsley G. & Gray T. How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein. Protein Sci 4, 2411–2423 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter G. Xia2: an expert system for macromolecular crystallography data reduction. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 43, 186–190 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Winter G., Lobley C. M. C. & Prince S. M. Decision making in xia2. Acta Crystallogr. D69, 1260–1273 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. Integration, scaling, space-group assignment and post-refinement. Acta Crystallogr. D66, 133–144 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman D. J. et al. Diffraction geometry refinement in the DIALS framework. Acta Crystallogr. D72, 558–575 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karplus P. A. & Diederichs K. Assessing and maximizing data quality in macromolecular crystallography. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 34, 60–68 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans P. R. & Murshodov G. N. How good are my data and what is the resolution? Acta Crystallogr. D69, 1204–1214 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CCP4. Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4, The CCP4 Suite: Programs for Protein Crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D50, 760–763 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebedev A. A. & Isupov A. Space-group and origin ambiguity in macromolecular structures with pseudo-symmetry and its treatment with the program Zanuda. Acta Crystallogr D70, 2430–2443 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy A. J. et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov G. N. et al. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr. D67, 355–367 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P. & Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D60, 2126–2132 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen V. B. et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D66, 12–21 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saff E. B. & Kuijlaars A. B. J. Distributing many points on a sphere. The Mathematical Intelligencer 19, 5–11 (1997). [Google Scholar]