Abstract

Background and Aims:

Spinal anaesthesia (SA) with bolus dose has rapid onset but may precipitate hypotension. When we inject local anaesthetic in fractions with a time gap, it provides a dense block with haemodynamic stability and also prolongs the duration of analgesia. We aimed to compare fractionated dose with bolus dose in SA for haemodynamic stability and duration of analgesia in patients undergoing elective lower segment caesarean section (LSCS).

Methods:

After clearance from the Institutional Ethics Committee, the study was carried out in sixty patients undergoing elective LSCS. Patients were divided into two groups. Group B patients received single bolus SA with injection bupivacaine heavy (0.5%) and Group F patients fractionated dose with two-third of the total dose of injection bupivacaine heavy (0.5%) given initially followed by one-third dose after 90 s. Time of onset and regression of sensory and motor blockage, intraoperative haemodynamics and duration of analgesia were recorded and analysed with Student's unpaired t-test.

Result:

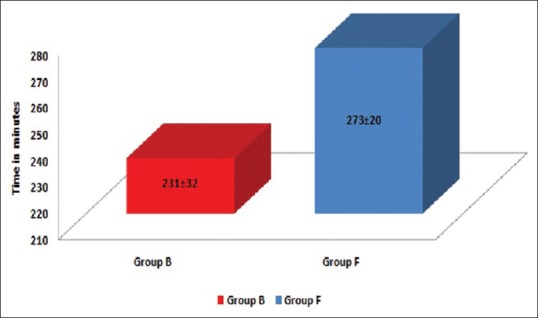

All the patients were haemodynamically stable in Group F as compared to Group B. Five patients in Group F and fourteen patients in Group B required vasopressor. Duration of sensory and motor block and duration of analgesia were longer in Group F (273.83 ± 20.62 min) compared to Group B (231.5 ± 31.87 min) P < 0.05.

Conclusion:

Fractionated dose of SA provides greater haemodynamic stability and longer duration of analgesia compared to bolus dose.

Keywords: Anaesthesia, dose fractionation, hypotension, spinal

INTRODUCTION

Spinal anaesthesia (SA) with bupivacaine is routinely used to provide anaesthesia for both elective and emergency caesarean section. SA has a rapid onset but at the same time, it precipitates hypotension. Maternal hypotension may lead to decrease in utero placental perfusion resulting in foetal acid-base abnormalities.[1]

To prevent maternal hypotension, there are various measures such as administration of fluids either colloids or crystalloids before SA, administration of a prophylactic vasopressor and left uterine displacement. The incidence of hypotension is reported to be 92%–94% when no preventive measures are taken to reduce hypotension.[2,3]

Dose of hyperbaric bupivacaine depends on factors such as weight, height, anatomy of spine and pregnancy for its intensity and duration of the spinal block. The study done by Danelli et al.[4] showed that the minimum effective dose of intrathecal bupivacaine providing effective spinal block in 95% of the women undergoing caesarean section to be 0.06 mg/cm height.

Sometimes bolus dose of the local anaesthetic agent in SA causes more hypotension. The fractionated dose of the local anaesthetic agent, in which two-third of the total calculated dose given initially followed by one-third dose after a time gap of 90 s, achieves adequate SA and provides a dense block with haemodynamic stability. There are no studies available which compared these two techniques in pregnant patients. We decided to do this prospective, randomised, double-blind study with the primary aim to compare fractionated dose versus bolus dose in SA for haemodynamic stability and duration of analgesia in patients undergoing elective lower segment caesarean section (LSCS). We have also compared the characteristics of sensory and motor block.

METHODS

After the Institutional Ethics Committee approval and written informed consent, the present study was carried out on sixty female patients (thirty in each group) of the American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status I–III, age from 18 to 40 years, height from 140 to 180 cm, singleton pregnancies scheduled for elective LSCS under SA. Patients with pre-existing diseases or pregnancy-induced hypertension, cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease, any contraindication to SA, those weighing <50 kg or >110 kg and those taller than 180 cm or shorter than 140 cm and severely altered mental status, spine deformities or history of laminectomy were excluded from the study.

Standard monitors including non-invasive blood pressure (NIBP), electrocardiogram (ECG) and pulse oximeter (SpO2) were attached to the patient, and baseline blood pressure and heart rate (HR) were recorded. Intravenous (IV) line was taken with 18-gauge IV cannula and patients were premedicated with ranitidine 1 mg/kg and ondansetron 0.1 mg/kg IV. The patients were preloaded with Ringer's lactate (RL) solution 10–15 ml/kg over 10 min.

SA was given in sitting position with 23-gauge Quincke spinal needle in L3–L4 or L4–L5 interspace after skin infiltration with lignocaine (2 ml, 2%). After aspiration of cerebrospinal fluid, injection bupivacaine 0.5% heavy was injected according to respective groups, B and F. Total dose of SA was calculated as 0.07 mg/cm of the height of the patient. The patients were randomly divided into two groups. Group B patients received a single bolus dose of bupivacaine over 10 s. Group F patients received fractionated dose of bupivacaine with two-third of the total calculated dose given initially followed by one-third dose after 90 s, both doses given at a rate of 0.2 ml/s. After injection of initial two-third dose, the syringe was kept attached to the spinal needle for remaining 90 s, after which remaining one-third dose was administered.

To prevent observer's bias, patients were kept sitting for 90 s after completion of the subarachnoid injection in Group B. Patients were turned into the supine position with a wedge under the right hip in both groups. We supplemented oxygen with the nasal cannula at 3 L/min.

The patients were randomly divided into two groups using computer-generated sequential number placed in sealed envelopes and opened only before the commencement of the study. The study was conducted in a double-blind fashion such that the patient and the assessor were unaware of the group. The assessor was kept blinded during the administration of the drug. Only the attending consultant administering the SA knew the group allocation.

We assessed and recorded time of onset, level and regression of motor and sensory block. Confirmation of sensory block was assessed by loss of sensation to pinprick. Motor blockage was assessed by a modified Bromage scale. These tests were performed every 5 min till the achievement of maximum sensory and motor block (Bromage scale 3) and every 30 min post-operatively until the sensory and motor variables were back to normal. The onset time of sensory or motor blockade was defined as the interval between intrathecal administration and time to achieve maximum block height or a modified Bromage score of 3, respectively.

The surgical incision was allowed when loss of pinprick sensation reached the T6 dermatome level bilaterally and when Bromage scale of three was achieved. Patients with inadequate sensory blockade and requiring conversion to general anaesthesia were excluded from the study.

Intraoperatively, patients were monitored with continuous ECG, HR, NIBP and SpO2. Hypotension was treated when mean arterial pressure (MAP) decreased ≤20% of baseline with injection mephentermine 5 mg given IV and repeated when needed. The number of hypotensive episodes and mephentermine used were recorded for each patient. We treated bradycardia if any (HR of < 60 beats/min) with IV atropine 0.6 mg.

The duration of sensory blockade was defined as the interval from intrathecal administration of local anaesthetic to S2 segment regression. The duration of motor blockade was defined as the time interval from the onset of motor block to the time of achievement of modified Bromage scale zero (0). Pain was assessed with the linear visual analogue scale (VAS) every 30 min post-operatively for the first 2 h then hourly up to 6 h. The duration of analgesia was defined as the time from intrathecal injection till the first demand for rescue analgesic when VAS was ≥4. The patient was given diclofenac sodium 75 mg intramuscular as rescue analgesic.

After delivery, we administered IV oxytocin 5 IU IV slowly and 15 IU in 500 ml RL. The incidence of nausea, vomiting, respiratory distress, shivering, pruritus, urinary retention was noted for 24 h post-operatively and treated accordingly. The attending paediatrician assessed Apgar scores at 1 and 5 min.

All the observations were recorded, and all the results were analysed statistically using Microsoft Excel 2007. Qualitative data such as age and maximum dermatome achieved were analysed statistically using Chi-square test. Quantitative data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analysed using the unpaired t-test. P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Sample size calculation was based on the pilot study, considering the difference in MAP changes of 6 mmHg after 15 min of SA. With an α-error of 0.05 and power of study 90%, the sample size came to 28. We enrolled thirty patients in each group considering the drop outs.

RESULTS

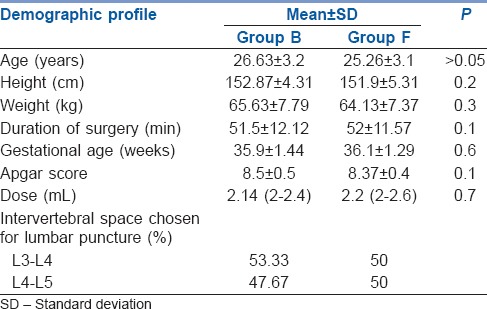

Both groups were comparable in their demographic profiles [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic variable and operative data

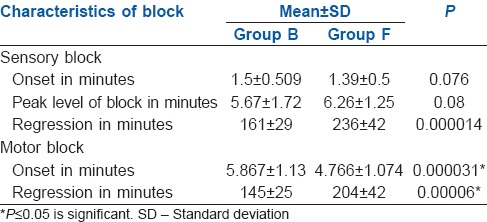

Onset of sensory and motor blockade was comparable between two groups while duration of sensory and motor regression was statistically significant among the two groups-161 ± 29 and 236 ± 42 min in Group F and 145 ± 25 and 204 ± 42 min in Group B, respectively, P < 0.05 [Table 2].

Table 2.

Characteristics of sensory and motor block

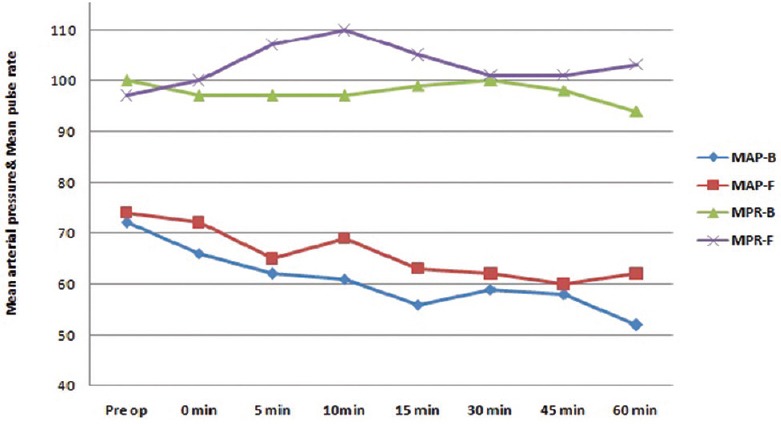

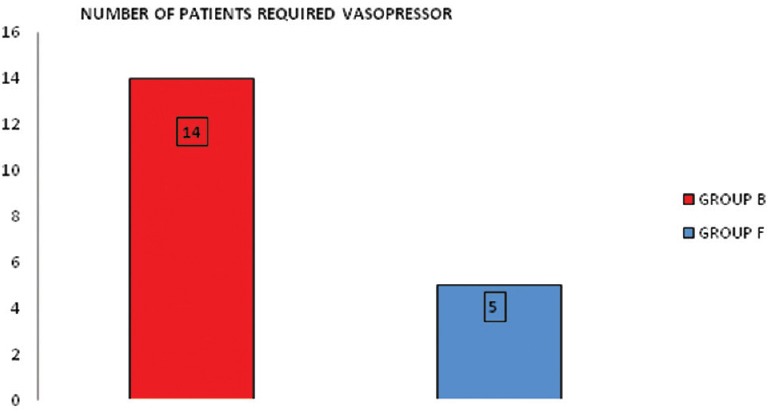

Patients were haemodynamically more stable in Group F as compared to Group B [Figure 1]. Five patients (16.66%) in Group F and 14 patients (46.66%) in Group B required vasopressor [P = 0.013, Figure 2]. Figure 3 shows a longer duration of analgesia with Group F as compared to Group B [P < 0.001].

Figure 1.

Intraoperative haemodynamic changes

Figure 2.

No. of patients requiring intraoperative vasopressor [P = 0.013]

Figure 3.

Duration of analgesia in minutes [P < 0.001]

One patient in Group B developed nausea and vomiting and one developed hypotension. One patient in each of the Groups B and F developed shivering. None of the patients developed dryness of mouth, pruritus, sedation, respiratory depression, bradycardia and headache in both groups.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of caesarean section deliveries has been rising rapidly; maternal hypotension and high spinal blockade are a common occurrence after SA with unadjusted doses of local anaesthetic. Maternal hypotension is the most common complication of SA with 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine with dosages between 12 and 15 mg. High SA has been reported with doses larger than 12 mg of bupivacaine in patients undergoing caesarean section.[5,6] Maintenance of normal maternal blood pressure is the key factor for neonatal outcome. A national survey at the United Kingdom revealed that a large variety of dosage regimens were in use for SA for caesarean section.[7]

In our study, we aimed to compare fractionated dose versus bolus dose in SA for haemodynamic stability and duration of analgesia in patients undergoing elective LSCS.

Clinical observational studies confirm that weight[8] and height[4] are significant variables in predicting the final level of the block. Some studies used a fixed dosage regimen while other studies have used the dose of bupivacaine according to the patient's characteristics. Harten compared the effects of two dosage regimens, fixed as well as adjusted dose and concluded that successful SA for caesarean section has been associated with a low incidence of hypotension with dosage regimen adjusted for height and weight.[9]

Schnider et al.[10] suggested that the onset time for achieving an adequate sensory level for surgery increases linearly with height and decreases with increasing weight while another clinical study demonstrated that the dose of intrathecal bupivacaine for caesarean delivery is similar in obese and normal weight women.[11] It is more difficult to predict the extension of the blockade when using the same dose of local anaesthetics in obese and non-obese pregnant women. A retrospective study observed a higher percentage of hypotension in pregnant women with obesity class three, which might be due to the greater extension of a higher sympathetic blockade caused by compression of the subarachnoid space by the pregnant abdomen associated with obesity.[12]

The need of local anaesthetic in SA is lower in pregnant patients. Mechanisms suggested for this include pregnancy-specific hormonal changes, which affect the action of neurotransmitters in the spinal column, increased permeability of neural membranes and other pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes.[13,14]

In the study conducted by Danelli et al.,[4] dose of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine in relation to patients height was used; they concluded that a dose as low as 0.06 mg/cm height represents the dose of intrathecal bupivacaine providing effective spinal block in 95% of women undergoing elective caesarean section. Similarly, we considered only height as a predictor for calculating the dose of bupivacaine. We conducted pilot studies of five cases with bupivacaine 0.06 mg/cm of height, but the adequate sensory level was not achieved. Hence, we used the dosage of 0.07 mg/cm height in our study.

In our study, bolus group received a mean (range) dose of 2.14 (2–2.4) ml whereas fractionated group received a mean (range) dose of 2.2 (2–2.6) ml which were comparable among the two groups. These doses are comparable to the fixed dose used in the study done by Harten et al.[9] Furthermore, a survey in the United Kingdom showed that the mean (SD) volume of bupivacaine 0.5% usually given is 2.57 ml with a fixed dosage scheme, whereas a mean volume of 2.34 ml with minimum volume ranges of 1.2–3.0 ml is given with a variable dose scheme.[7]

We did not observe sensory blockade above T4 level in either group as shown in Table 2. Russell and Holmqvist[15] found 25% of patients undergoing LSCS developed sensory blocks to the cervical dermatomal region, of which 10% extended to C1 or C2 when they used fixed dose of hyperbaric bupivacaine 0.5% 2.5 ml. Harten's study results showed that 17% of the patients presented with cervical dermatomal block levels in the fixed-dose group and only 4.5% of the patients in the adjusted dose group reported cervical dermatomal block levels.[9] The study suggested that adjusting the dose to height and weight increases the safety margin of SA.

Fahmy[16] compared the circulatory and anaesthetic effects of bolus versus fractionated administration of bupivacaine. He found that fractionated dose of bupivacaine prolonged the duration of action and is associated with more circulatory stability. He concluded that when the same dose of bupivacaine is administered in a fractionated manner, it is associated with a prolonged duration of sensory and motor blockade and lesser degree of hypotension. Favarel et al. studied sixty elderly patients undergoing surgery for hip fracture for haemodynamic tolerance of titrated doses of bupivacaine versus single dose SA and concluded that titrated doses of bupivacaine was safe, efficient and provided better haemodynamic stability than single dose SA.[17] The results of above studies were comparable with ours.

We used mephentermine for control of maternal blood pressure during caesarean section. Bhardwaj et al.[18] compared the three vasopressors ephedrine, phenylephrine and mephentermine for control of maternal blood pressure during caesarean section and concluded that all three were equally effective in maintaining maternal blood pressure as well as umbilical PH during SA for caesarean section.

In our study, we found more hypotension when single bolus dose was used for SA in LSCS; however, the use of fractionated dose given intrathecally produced a longer duration of surgical analgesia with a minimal requirement of vasopressors and no undesired side effects such as hypotension. Apgar scores were almost similar in both groups in our study.

The limitations of our study were that we had assessed neonatal outcome by Apgar score only and did not include umbilical cord blood gas values and pH or uteroplacental blood flow. Hence, we were unable to comment further on uteroplacental perfusion.

Further studies and research comparing bolus and fractionated dose in pregnancy-induced hypertensive patients undergoing LSCS can be done to evaluate the effectiveness of fractionated dose in maintaining haemodynamic stability.

CONCLUSION

Fractionated dose of SA provides greater haemodynamic stability and longer duration of analgesia compared to bolus dose in patients undergoing elective caesarean section. To prevent sudden hypotension, fractionated dose of SA can be an acceptable and safe alternative in LSCS.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the Department of Gynaecology, P.D.U. Medical College, Rajkot.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ben-David B, Solomon E, Levin H, Admoni H, Goldik Z. Intrathecal fentanyl with small-dose dilute bupivacaine: Better anesthesia without prolonging recovery. Anesth Analg. 1997;85:560–5. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199709000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moran DH, Perillo M, LaPorta RF, Bader AM, Datta S. Phenylephrine in the prevention of hypotension following spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery. J Clin Anesth. 1991;3:301–5. doi: 10.1016/0952-8180(91)90224-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riley ET, Cohen SE, Rubenstein AJ, Flanagan B. Prevention of hypotension after spinal anesthesia for cesarean section: Six percent hetastarch versus lactated Ringer's solution. Anesth Analg. 1995;81:838–42. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199510000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danelli G, Zangrillo A, Nucera D, Giorgi E, Fanelli G, Senatore R, et al. The minimum effective dose of 0.5% hyperbaric spinal bupivacaine for cesarean section. Minerva Anestesiol. 2001;67:573–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finucane BT. Spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery. The dosage dilemma. Reg Anesth. 1995;20:87–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Simone CA, Leighton BL, Norris MC. Spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery. A comparison of two doses of hyperbaric bupivacaine. Reg Anesth. 1995;20:90–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyne I, Varveris D, Harten J, Brown A. National survey of dose of hyperbaric bupivacaine for elective caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia at term. Int J Obstet Anaesth. 2002;11:20. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCulloch WJ, Littlewood DG. Influence of obesity on spinal analgesia with isobaric 0.5% bupivacaine. Br J Anaesth. 1986;58:610–4. doi: 10.1093/bja/58.6.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harten JM, Boyne I, Hannah P, Varveris D, Brown A. Effects of a height and weight adjusted dose of local anaesthetic for spinal anaesthesia for elective caesarean section. Anaesthesia. 2005;60:348–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schnider TW, Minto CF, Bruckert H, Mandema JW. Population pharmacodynamic modeling and covariate detection for central neural blockade. Anesthesiology. 1996;85:502–12. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199609000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norris MC. Patient variables and the subarachnoid spread of hyperbaric bupivacaine in the term parturient. Anesthesiology. 1990;72:478–82. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199003000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodrigues FR, Brandão MJ. Regional anesthesia for cesarean section in obese pregnant women: A retrospective study. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2011;61:13–20. doi: 10.1016/S0034-7094(11)70002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saravanakumar K, Rao SG, Cooper GM. Obesity and obstetric anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2006;61:36–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andreasen KR, Andersen ML, Schantz AL. Obesity and pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:1022–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russell IF, Holmqvist EL. Subarachnoid analgesia for caesarean section. A double-blind comparison of plain and hyperbaric 0.5% bupivacaine. Br J Anaesth. 1987;59:347–53. doi: 10.1093/bja/59.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fahmy NR. Circulatory and anaesthetic effects of bupivacaine for spinal anaesthesia fractionated vs. bolus administration. Anaesthesiology. 1996;3:85. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Favarel GJ, Sztark F, Petitjean ME, Thicoipe M, Lassie P, Dasbadie P. Haemodynamic effects of spinal anaesthesia in the elderly: Single dose versus titration through a catheter. Reg Anaesth Pain Med. 1999;24:417–42. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199602000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhardwaj N, Jain K, Arora S, Bharti N. A comparision of three vasopressors for tight control of maternal blood pressure during caeserean section under spinal anaesthesia: Effect on maternal and foetal outcome. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2013;29:26–31. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.105789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]