Abstract

The tunability of electrical polarization in ferroelectrics is instrumental to their applications in information-storage devices. The existing ferroelectric memory cells are based on the two-level storage capacity with the standard binary logics. However, the latter have reached its fundamental limitations. Here we propose ferroelectric multibit cells (FMBC) utilizing the ability of multiaxial ferroelectric materials to pin the polarization at a sequence of the multistable states. Employing the catastrophe theory principles we show that these states are symmetry-protected against the information loss and thus realize novel topologically-controlled access memory (TAM). Our findings enable developing a platform for the emergent many-valued non-Boolean information technology and target challenges posed by needs of quantum and neuromorphic computing.

The binary information technology reaches its limits set by the atomic size miniaturization and by the fundamental Landauer principle of energy dissipation per bit processing1. Employing many-valued logic units, implemented as memory multi-level cells (MLC), reduces energy losses and enables to pack unprecedented high-density information within a single digit overcoming the binary tyranny2,3,4. However, existing implementations of MLC that are currently used in the solid state drives and flash memories, require analogue methods of the bits writing leading to erratic behaviour of the cell due to stochastic loss of information5. Here we step in the breach and use an opportunity offered by ferroelectric materials6,7 that are currently used for implementation of the binary random access memory units8. We reach further and utilize the ferrolelectric cubic multiaxiality inherent to ferroelectric perovskite oxides. The target systems are the perovskite thin films, where the substrate-induced strain converts the cubic symmetry to the tetragonal one, enabling the binary up-and-down polarization orientation. However, lifting the cubic degeneracy of the polarization orientations opens yet a new richness of the multi-stable polarization directions (states) in the films, which are not available in the bulk systems. Here we show that these states enable the design of the enhanced performance memory units, ferrolectric multibit cells (FMBC), with the non-trivial topological access to the memory levels by the specific protocol of the applied electric field. The advantage offered by the FMBC as compared to other widely discussed implementations of MLC based on the either of the spin-torque memristive effect9, the domain formation in ferroelectric nanodots10, the hybrid design11,12, the DNA-based storage13, and the sequential polarization rotation14, to name a few, is that while maintaining the simplicity of the material realization, the FMBC ensure the symmetry protection of the memory levels and the strain-temperature programmable architecture of accessing stored information.

Results

Multibit hysteresis

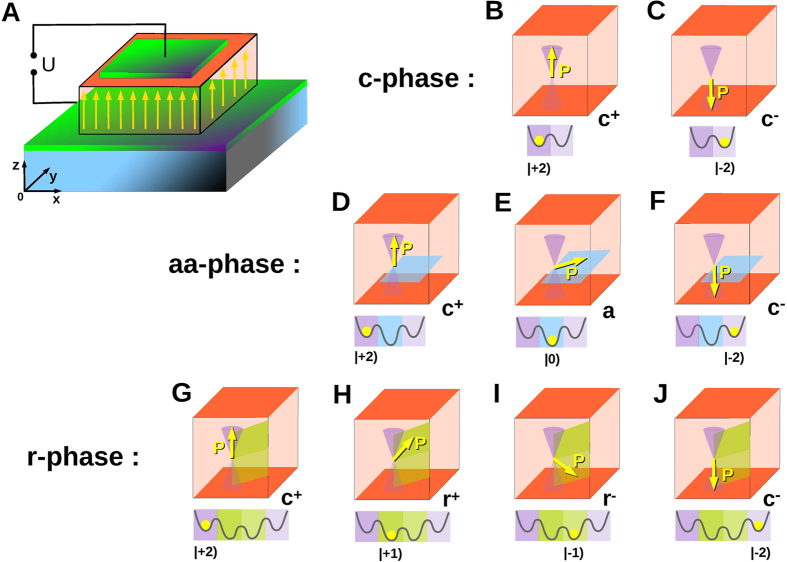

Shown in Fig. 1 are the experimental setup (A) and the generic ferroelectric phases emerging in strain oxide films (B to J). Each phase is characterized by the stable orientation of the polarization vector, P = (P1, P2, P3), where xyz components are referred to as {123}, and can possess also several metastable orientations. These phases may be realized in PbTiO315 and in Pb(Zr1−xTix)O3 (1 > x > 0.4)16 at different strains, um and temperatures, T. The c-phase appears, as a rule, at the epitaxial compressive strains and harbors two stable degenerate states, c±, of z-oriented polarization, (0, 0, ±P3), (Fig. 1B and C). The aa-phase, having four stable degenerate states of polarization, (±P1, ±P1, 0) oriented along the xy-face diagonals of the tetragonal unit cell, appears at high tensile strains. One of these a-states with the positive x and y components of in-plane polarization is shown in Fig. 1E, the others are obtained by the consecutive C4 rotations over 90° around z-axis. In a r-phase, appearing at low tensile strains, the equilibrium polarization is directed approximately along one of the space diagonals of the tetrahedral unit cell, hence allowing for eight degenerate orientations (±P1, ±P1, ±P3). Two out of eight r-states, denoted as r+ and r−, with the positive and negative z-components and positive x- and y components, are displayed in Fig. 1H and I, the others are obtained by C4 rotations.

Figure 1. Multistable polarization states in the ferroelectric film.

(A) Sketch of the experimental setup and coordinate axes (xyz). The ferroelectric cell (orange) is grown on the substrate (blue) and is sandwiched between the two electrodes (green). The electric field produced by the voltage operates the polarization orientation. (B) and (C) The c-phase possessing two stable states, c+ and c− of polarization vector, P. (D) to (F) The aa-phase having one stable state, a, and allowing for two additional metastable states, c+ and c− of P. (G) to (J) The r-phase possessing two stable states, r+ and r−, and allowing for two additional metastable states, c+ and c− of P. The lower sub-panels display the positions of the corresponding polarization states in the minima of the energy relief (yellow spheres) and the respective logical quantum (loq)-numbers.

We build the memory cells with different number of logic states (energy levels) on the wealth of the above phases. Note, that the c-phase, having only two, “up” and “down” oriented polarization states, c− and c+, is a traditional material platform for the binary memory. The promised FMBC with larger number of states adopts r and aa phases. The key point here is that phases aa and r maintain not only their inherent stable polarization states, a and r± respectively, but also can acquire the metastable ones, c± (Fig. 1D,F and G,J, respectively). These latter states are the legacy of the polarization stable states of the tetragonal ferroelectric phase that would exist in the bulk material without clamping. Lying in the global and local energy minima, all these stable and metastable states are protected by the pseudo-cubic structure of the system and are thus resistant against the moderate perturbations. As a result, a ferroelectric cell can serve as the symmetry-protected memory storage unit. We quantify the stored information by logical quantum (loq)-numbers, which are |0) for state a, |±1) for states r±, and |±2) for states c± correspondingly. The ordinary binary memory cell constructed from the c-phase possesses two loqs |±2) corresponding to c± states. The FMBC which we propose are built on the aa and r phases. The a-phase-based FMBC can have three loqs |0) and |±2), corresponding to a and c± states. The r-phase-based FMBC can have four loqs |±1) and |±2), corresponding to r± and c± states.

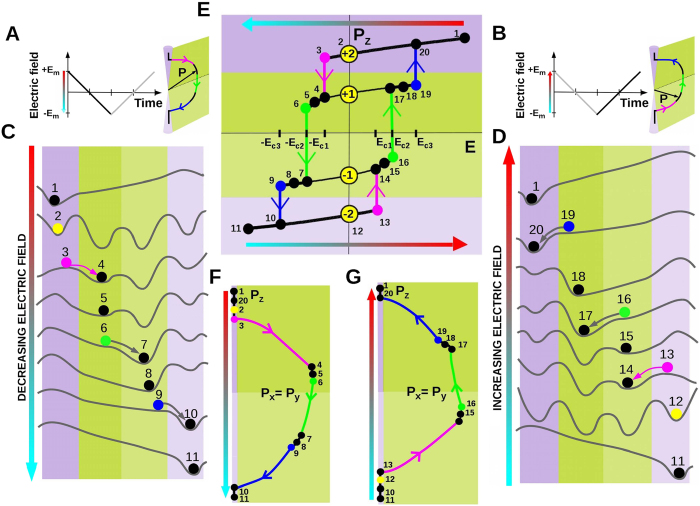

Switching the polarization between the different loqs, hence operating the FMBC, is achieved by applying and then varying the z-aligned electric field, E, induced by electrodes. An exemplary operational roadmap for the r-phase is shown in Fig. 2. One starts with the complete poling of the FMBC to the up-oriented c+ state. The gradual decrease of the applied field from the maximal Em > 0 to minimal −Em (Fig. 2A) rotates the polarization vector from the up-oriented c+ state to the down-oriented c− state17,18. The backward field reversely takes P to the state c+ (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Multibit switching process.

(A) Positive-to-negative variation of the electric field (left) and the corresponding polarization vector rotation in the Px = Py plane (right). (B) Reversal negative-to-positive field change and the corresponding polarization rotation. (C) Evolution of the potential relief corresponding to varying electric field from +Em to −Em. Color circles show sequential positions of the system. Polarization passes through all multistable states, c+, r+, r− and c−. The point 1 marks the c+ state, corresponding to the initial positive electric field. Upon decreasing the field below E = 0 (2) till the critical field −Ec1 (3) the system looses its stability against the jump to the state r+ (4). It stays in this state (5) till another critical field, −Ec2 is achieved at point 6 and then jumps down to the state r− (7). Further field decrease takes the system sequentially through the points 7, 8, and 9. Point 9 corresponds to destabilizing of the state r− at the critical field −Ec3. The system falls into the state c− (10) and stays there till the final negative field (11). (D) Same as panel (C) but under the negative-to-positive field change. Reversing the field variation drives the system back, closing the field cycle at the initial point 1. (E) The multilevel hysteresis loop spanned by the polarization vector upon the positive-to-negative and the reversed variation of the field E. It visualizes possible switching between all the four memory logical quantum (loq)-numbers, |±2) and |±1) associated with the states c± and r± at E = 0. The cycle, 1 → 2 → … → 11 → 12 → …. → 20 → 1, provides an access to the states with memory logical quantum (loq)-numbers |±2). Access to other loqs, |±1) can be achieved by the partial cycles. For example, the cycle 20 → 2 → 3 → 4 → 17 → 18 → 19 → 20 enables switching between the loqs |+2) and |+1). (F) Trajectory of the polarization vector in the plane with Px = Py leading to 1 → 11 half-cycle. (G) The same as in (F) but depicting 11 → 1 half-cycle due to the reversed field variation.

On its way the polarization repeatedly gets stuck in the energy minima inherited from the equilibrium states c+, r+, r− and c−. An example of evolution of the potential relief for P under the field-induced bias on the descending branch is shown in Fig. 2C. The transitions between these states occur at critical fields −Ec1, −Ec2 and −Ec3 at which the separating energy barriers vanish. The corresponding evolution for the ascending branch is shown in Fig. 2D. The polarization hysteresis loop, P3(E), realizing the complete Em → −Em → Em field variation cycle and the trajectories of the polarization vector P are shown in Fig. 2E,F and G. The loop comprises three closed cycles: 20 ↔ 3 → 4 ↔ 19 → 20; 6 → 7 ↔ 16 → 17 ↔ 6 and 9 → 10 ↔ 13 → 14 ↔ 9, which take the FMBC to states c+ (branch 3 ↔ 20), r+ (branch 6 ↔ 19), r− (branch 9 ↔ 16) and c− (branch 10 ↔ 13). Switching off the field when the system moves over one of these branches stalls the memory to the loqs |−2), |−1), |+1), and |+2), respectively. Hereby, constructing an appropriate field variation protocol one gets access to all the four loqs of the multibit memory cell.

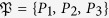

Model

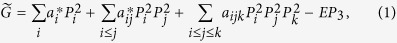

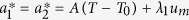

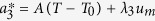

Description of the uniaxially-strained perovskite ferroelectric film, rests on the minimization of the Landau-Devonshire functional (LDF) written in a form proposed in ref. 15

|

where the 2nd-order coefficients  and

and  depend on the misfit strain um and temperature T, and the 4th-order coefficients obey the tetragonal symmetry conditions

depend on the misfit strain um and temperature T, and the 4th-order coefficients obey the tetragonal symmetry conditions  ,

,  . The 6th-order coefficients conserve the cubic symmetry, a111 = a222 = a333, a112 = a113 = a223. The last term in (1) presents the interaction of polarization with electric field. The standard extended form of the LDF (1) and the expression derived from it are presented in the Methods section.

. The 6th-order coefficients conserve the cubic symmetry, a111 = a222 = a333, a112 = a113 = a223. The last term in (1) presents the interaction of polarization with electric field. The standard extended form of the LDF (1) and the expression derived from it are presented in the Methods section.

Energy landscape, bifurcations and catastrophes

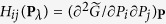

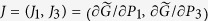

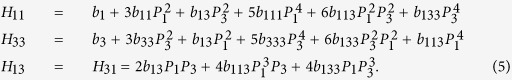

The hysteretic jumps between loqs upon the continuous variation of the driving parameter flag the bifurcation-type instabilities which are described and classified by the catastrophe theory19,20. To describe the switching process we first study the energy landscape of the system under the fixed applied field, E. To this end, we minimize the LDF with respect to the position of P in the configurational space  . The loci of extrema, {Pλ}, λ = 1, 2, 3 ... in

. The loci of extrema, {Pλ}, λ = 1, 2, 3 ... in  are defined by the condition J(Pλ, E) = 0, where

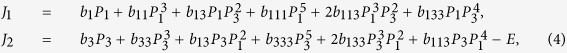

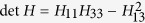

are defined by the condition J(Pλ, E) = 0, where  is the Jacobian vector (the so-called Morse points20). The extrema in which the Hessian matrix,

is the Jacobian vector (the so-called Morse points20). The extrema in which the Hessian matrix,  is positively defined correspond to the LDF minima. Varying the field alters the energy relief, in particular, the number and positions of the extrema Pλ(E) in

is positively defined correspond to the LDF minima. Varying the field alters the energy relief, in particular, the number and positions of the extrema Pλ(E) in  . Following the behaviour of a specific minimum, one observes that as soon as the corresponding Hessian matrix ceases to be positive definite at the critical field defined by the condition

. Following the behaviour of a specific minimum, one observes that as soon as the corresponding Hessian matrix ceases to be positive definite at the critical field defined by the condition  (the non-Morse degenerate point) the bifurcation occurs, the system turns unstable and switches into an adjacent energy favorable state.

(the non-Morse degenerate point) the bifurcation occurs, the system turns unstable and switches into an adjacent energy favorable state.

Focusing on the switching between the polarization states r± and c±, we reduce the configuration space for the LDF (1) to the 2D plane  = {P1, P1, P3} ⊂

= {P1, P1, P3} ⊂  , where P1 = P2. To trace hysteresis branches Pλ(E) ∈

, where P1 = P2. To trace hysteresis branches Pλ(E) ∈  with λ = {c−, r−, r+, c−} and determine their critical end-points and corresponding critical fields, we solve the equations for the minima conditions numerically. The advantage of the general catastrophe theory approach is that the type of the catastrophe and the corresponding critical behavior is stable against perturbations, provided the symmetry of the Landau functional preserves21. This enables to carry out the complete analysis of the bifurcations at the critical fields Ec1, Ec2 and Ec3 using the LDF (1), linearized in the vicinity of the instability points in

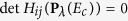

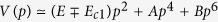

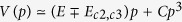

with λ = {c−, r−, r+, c−} and determine their critical end-points and corresponding critical fields, we solve the equations for the minima conditions numerically. The advantage of the general catastrophe theory approach is that the type of the catastrophe and the corresponding critical behavior is stable against perturbations, provided the symmetry of the Landau functional preserves21. This enables to carry out the complete analysis of the bifurcations at the critical fields Ec1, Ec2 and Ec3 using the LDF (1), linearized in the vicinity of the instability points in  space. The type of the catastrophe is determined by the corresponding catastrophe potential function, V(p), where p is the deviation of polarization along the instability direction. Thus, the four-fold symmetry of c±-states imposes the even-terms in the potential,

space. The type of the catastrophe is determined by the corresponding catastrophe potential function, V(p), where p is the deviation of polarization along the instability direction. Thus, the four-fold symmetry of c±-states imposes the even-terms in the potential,  near Ec1, resulting in the butterfly catastrophe. At the same time, for Ec2 and Ec3 the generic position of the r±-states in

near Ec1, resulting in the butterfly catastrophe. At the same time, for Ec2 and Ec3 the generic position of the r±-states in  plane yields the fold catastrophe with

plane yields the fold catastrophe with  . Establishing the type of the catastrophe is important for the correct identification of the thermodynamic criticallity and slowing down of the system, occurring near the instability.

. Establishing the type of the catastrophe is important for the correct identification of the thermodynamic criticallity and slowing down of the system, occurring near the instability.

Switching dynamics in PbTiO3

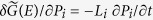

The dynamics of the switching process is described by numerical solution of the time-dependent Landau-Khalatnikov equations  , were Li are the damping coefficients. Let the system be at some arbitrary initial loq. Upon the gradual turn of the electric field, the polarization P(t) follows quasi-statically the varying E(t) and moves along the corresponding hysteresis branch. As the critical non-Morse point is achieved, the instability occurs and the system falls into another state located at the different hysteresis branch. This final state is determined by the time-dependent simulations. Further, turning off the field allows the system to slide along the new hysteresis branch and concludes system’s switching to a new loq.

, were Li are the damping coefficients. Let the system be at some arbitrary initial loq. Upon the gradual turn of the electric field, the polarization P(t) follows quasi-statically the varying E(t) and moves along the corresponding hysteresis branch. As the critical non-Morse point is achieved, the instability occurs and the system falls into another state located at the different hysteresis branch. This final state is determined by the time-dependent simulations. Further, turning off the field allows the system to slide along the new hysteresis branch and concludes system’s switching to a new loq.

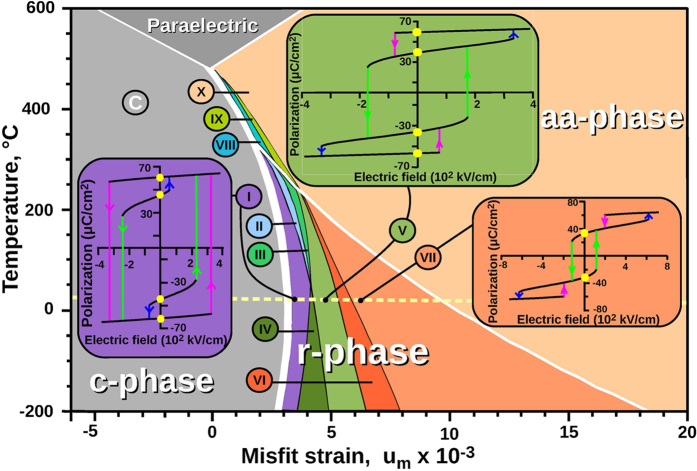

To develop multibit operation principles for FMBC, we investigate into a hysteretic behaviour of the polarization of the strained PbTiO3 film in an applied field. To this end we choose the material coefficients in the LDF (1), as proposed in ref. 15, and discuss the behaviour of the system as function of controlling parameters, temperature, T and misfit strain, um. The um–T phase diagram contains three background ferroelectric phases, c, aa, r, and paraelectric phase, calculated in ref. 15 (Fig. 3). That the c-r and c-aa phase transitions are of the first order, implies that these phases coexist along the transition lines. An applied field lifts the up/down degeneracy of the polarization resulting in the even more rich variety of the coexisting states, c+, r+, r−, and c− in the vicinity of the c-r transition and c+, aa, and r− in the vicinity of the c-aa transition. The interplay between these states gives rise to a remarkable wealth of the switching regimes in aa- and r-phases, shown as color strips in the Fig. 3. Importantly, the films that realize the FMBC are well screened by the electrodes so that the depolarization field vanishes and the ferroelectric 180° Landau-Kittel domains do not form. At the same time, the films are sufficiently thin, therefore, the substrate-induced strain cannot relax via the ferroelastic domain formation22. As a result, the film retains the monodomain state. Moreover, in ultrathin films the critical nucleus does not fit into the film and switching between the monodomain states occurs via the direct polarization turn23, bypassing the critical nucleation mechanism24.

Figure 3. Misfit strain - temperature, um−T, phase diagram of multibit switching regimes in PbTiO3 FMBC.

The background regions of paraelectric and ferroelectric (c, r, aa) phases are those calculated by15 and shown in Fig. 1(B) of that paper. Thick white line corresponds to the first order transition between these phases and thin lines stand for the second order transitions. The domains corresponding to different switching regimes are shown as color sectors. The insets display calculated topologically different 4-states hysteresis loops that are realized at room temperature (the room temperature is marked by the dashed yellow line). The loop V corresponds to the 4-loqs (2-bits) fully-switchable FMBC shown in Fig. 2; the loop I displays the 4-loqs FMBC in which 2 loqs are hidden; the loop VII shows the 2-loqs FMBC in which two additional states exist only in non-zero field.

Topology of multibit switching

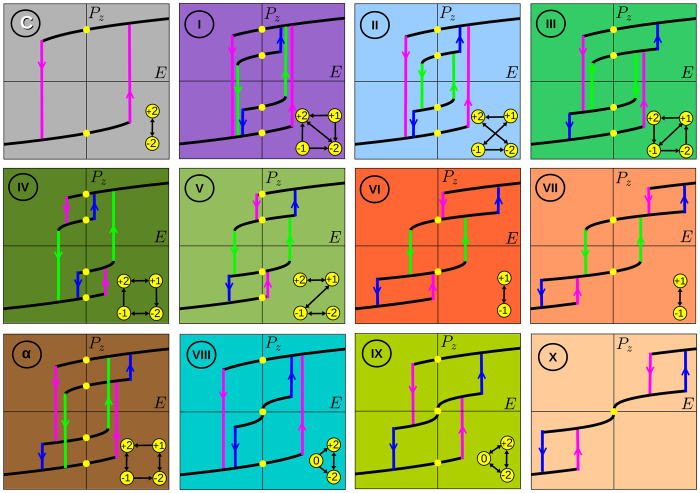

Insets to Fig. 3 show representative examples of the hysteresis loops, corresponding to phases I, V and VII, derived from the described above catastrophe theory analysis of LDF (1) and time-dependent simulations. These topologically different loops are realized in the r−phase region at room temperature and at different tensile strains. We start with the description of the 4-loqs loops. The hysteresis loop of type V, which occupies the relatively large strain interval, is already shown in Fig. 2 and discussed above as a typical 4-loqs configuration.

The loop of type I also has 4 loqs, but two of them corresponding to r+ and r− states, |+1) and |−1), are hidden for the repetitive switching. Once the polarization left them, it cannot return back by field variation. It is possible, however, to reach these stable states by the thermal rebooting the system, heating it up to the paraelectric phase and then cooling it back at the zero field. This process represents what we call the hidden-loq memory loops. Finally, the loop VII has only two stable loqs, |+1) and |−1) at E = 0 (states r+ and r−), whereas two other switchable states, c+ and c−, exist only at finite fields.

The topologically different hysteresis loops accounting for all combinatorial possibilities of switching procedures are presented in Fig. 4. The richness of the switching protocols rests on possible permutations of the critical fields where the memory states lose their stability (like the already mentioned Ec1, Ec2, and Ec3 in r phase). All these processes, except that of panel α, are realized in different parts of the um–T phase diagram. The loops are listed in the order of their appearance there, when going from c-phase (panel C) to r-phase (panels I-VII) and then to aa-phase (panels VIII-X). The bottom-right corners of the panels show the corresponding logical operation switching maps. The initial panel C displays the standard generic two-bits hysteresis loop, realized in the c-phase with the two available states c+ and c− corresponding to loqs |+2) and |−2). As we have already mentioned, from the topology viewpoint, the switching loops can be divided into three classes. Namely, (i) The full-loqs FMBC (panels III-V, α and IX) that allow (re-)switching between all the available states; (ii) The hidden-loqs FMBC (panels I, II and VIII), where two or one states are inaccessible; and (iii) The cells with two (panels VI, VII) and one (panel X) loq(s), respectively, where two additional states arise upon applying an external field.

Figure 4. Topologically different multibit hysteresis loops.

The number of the panels indicate the region of the phase diagram shown in the Fig. 3. The maps of the switching logical operations are shown in the right bottom corners of the respective panels. C: The traditional one-loop switching between two loqs, |+2) and |−2), the corresponding c+ and c− states are realized in the c-phase. I-VII: Multi-loop switching process between states c+, r+, r−, and c− in the r-phase. Panels I and II correspond to four-loqs unit in which two loqs are hidden. The four-loqs units with topologically-different full access to loqs are shown in panels III, IV and V. Panels VI and VII show the two-loq process in which two more switchable states are accessible in the nonzero field. One more four-loqs process that completes the set of topologically possible configurations is presented in panel α. This regime is not realized in the phase diagram of PbTiO3 (Fig. 3). The last three panels, VIII, IX, and X enlist the possible switching process in aa−phase. Three-loqs loops VIII (with one hidden loq) and IX can serve as platforms for the ternary logical units. The linear sequential configuration IX exhibits properties similar to the recently realized in bismuth ferrite thin films in ref. 14. The double loop X has only one stable loq, but two other switchable states can be realized in nonzero electric fields.

Discussion

The proposed FMBC enables the logical operations that are radically different from those provided by the existing MLCs. Namely, the latter allow only for the sequential switching between the available states that can be viewed as a linear one-dimensional chain of events. The ferroelectric multibit cells take all the advantages offered by the 2D topology of the switching maps and, depending on the specific hysteresis loop, can implement different paths of the access to the stored information. For instance, the loop V holds the traditional sequential reversible access from loq |−2) to loq |−1), then, from loq |−1) to loq |+1) etc, whereas in the loop III the loq |+1), is directly accessible from both loq |−1) and loq |−2). We have thus introduced a new type of the topological access memory (TAM), in which the protocol of the access to the symmetry protected quantized logical states can be engineered and tuned by the applied strain and/or temperature.

We have demonstrated that FMBC can be realized using the ultrathin films of ferroelectric oxides. The promising material that provides room temperature operations is a classical ferroelectric PbTiO3. One has to ensure that the system falls into the region of the r-phase in the phase diagram in Fig. 3, remaining not far from the first-order transition line, where all the variety of the switching regimes occurs. The task can be fulfilled by choosing substrate materials from the family of scandate oxide single crystals, which ensures tailoring of the necessary weak tensile strains25. Moreover, it justified theoretically26 and demonstrated experimentally25 that the 5-nm PbTiO3 film is fully coherent with the substrate DyScO3 and that no strain-relaxing dislocations and twins form. Thus at room temperature the strained state in the PbTiO3 film is in the state compatible with the r-phase, in which the polarization deviates away from the tetragonal axis. In this state, the ferroelastic domains are absent and the 180° polarization domains relax off over the time so that the final state appears the monodomain one. The feasibility of realization of four-state sequential loop V was also demonstrated recently for multiferroic BiFeO3 compound at T = 0 by numerical simulations27. A challenging task of inducing the uniform monodomain switching needed for the FMBC, can be addressed through polarization engineering via varying the oxygen chemical potential at the film surface as proposed in the pioneering work23 for a similar system PbTiO3/SrTiO3.

Methods

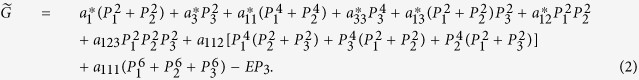

The explicit form of the functional (1) is written as:

|

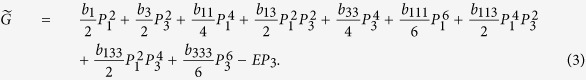

In the plane where P1 = P2 we use only two variational parameters, P1 and P3, simplifying Eq. (2) to:

|

where  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , b111 = 12a111 + 12a112, b113 = 2a123 + 4a112, b133 = 4a112 and b333 = 6a111.

, b111 = 12a111 + 12a112, b113 = 2a123 + 4a112, b133 = 4a112 and b333 = 6a111.

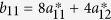

Then, the components of the corresponding Jacobian vector,  , are expressed as:

, are expressed as:

|

and the corresponding elements of the Hessian matrix  (i, j = 1, 3) as:

(i, j = 1, 3) as:

|

The determinant of the Hessian matrix is calculated as  .

.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Baudry, L. et al. Ferroelectric symmetry-protected multibit memory cell. Sci. Rep. 7, 42196; doi: 10.1038/srep42196 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Acknowledgments

We thank to N. Lemee and A. Razumnaya for clarification of the experimental situation in strained PbTiO3 films. This work was supported by ITN-NOTEDEV FP7 mobility program (I.L.) and by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division (V.V. and partly I.L.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions L.B., I.L. and V.V. equally contributed into conceiving the work, performing calculations, discussing the results of the work, and writing the manuscript.

References

- Landauer R. Irreversibility and heat generation in the computing process. IBM journal of research and development 5, 183–191 (1961). [Google Scholar]

- Torelli G., Lanzoni M., Manstretta A. & Riccò B. Multilevel flash memories. In Flash Memories 361–397 (Springer, 1999). [Google Scholar]

- Kryder M. H. & Kim C. S. After hard drives - what comes next? IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 45, 3406–3413 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Shyu Y.-T. et al. Effective and efficient approach for power reduction by using multi-bit flip-flops. IEEE transactions on very large scale integration (vlsi) systems 21, 624–635 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Cappelletti P. & Modelli A. Flash memory reliability. In Flash Memories. 399–441 (Springer, 1999). [Google Scholar]

- Ahn C., Rabe K. & Triscone J.-M. Ferroelectricity at the nanoscale: local polarization in oxide thin films and heterostructures. Science 303, 488–491 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawber M., Rabe K. M. & Scott J. F. Physics of thin-film ferroelectric oxides. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 1083–1130 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Scott J. F. Ferroelectric memories, vol. 3 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Locatelli N., Cros V. & Grollier J. Spin-torque building blocks. Nat. Mater. 13, 11–20 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martelli P.-W., Mefire S. M. & Luk’yanchuk I. A. Multidomain switching in the ferroelectric nanodots. Europhys. Lett. 111, 50001 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. A., Caraveo-Frescas J. A. & Alshareef H. N. Hybrid dual gate ferroelectric memory for multilevel information storage. Organic Electronics 16, 9–17 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Quindeau A. et al. Four-state ferroelectric spin-valve. Sci. Rep. 5, 9749 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church G. M., Gao Y. & Kosuri S. Next-generation digital information storage in DNA. Science 337, 1628–1628 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Chu K., Kim K.-E., Seidel J. & Yang C.-H. Out-of-plane three-stable-state ferroelectric switching: Finding the missing middle states. Phys. Rev. B 93, 115142 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Pertsev N. A., Zembilgotov A. G. & Tagantsev A. K. Effect of Mechanical Boundary Conditions on Phase Diagrams of Epitaxial Ferroelectric Thin Films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 1988–1991 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Pertsev N. A., Kukhar V. G., Kohlstedt H. & Waser R. Phase diagrams and physical properties of single-domain epitaxial Pb(Zr1-xTix)O3 thin films. Phys. Rev. B 67, 054107 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi Y. & Iwata M. Theory of morphotropic phase boundary in solid-solution systems of perovskite-type oxide ferroelectrics: Elastic properties. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 38, 1454–1458 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Baudry L., Luk’yanchuk I. A. & Razumnaya A. Dynamics of field-induced polarization reversal in thin strained perovskite ferroelectric films with c-oriented polarization. Phys. Rev. B 91, 144110 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Zeeman E. C. Catastrophe theory: Selected papers 1972–1977 (Addison-Wesley, 1977). [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore R. Catastrophe theory for scientists and engineers (Courier Corporation, 1993). [Google Scholar]

- Arnol’d V. I. Catastrophe theory (Springer Science & Business Media, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- Speck J. & Pompe W. Domain configurations due to multiple misfit relaxation mechanisms in epitaxial ferroelectric thin films. i. theory. Journ. of Appl. Phys. 76, 466–476 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Highland M. J. et al. Polarization switching without domain formation at the intrinsic coercive field in ultrathin ferroelectric PbTiO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 167601 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landauer R. Electrostatic considerations in BaTiO3 domain formation during polarization reversal. Journ. of Appl. Phys. 28, 227–234 (1957). [Google Scholar]

- Catalan G. et al. Polar domains in lead titanate films under tensile strain. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 127602 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Q., Nagarajan V. & Alpay S. Film thickness versus misfit strain phase diagrams for epitaxial pbtio 3 ultrathin ferroelectric films. Physical Review B 78, 064117 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Stengel M. & Íñiguez J. Electrical phase diagram of bulk BiFeO3. Phys. Rev. B. 92, 235148 (2015). [Google Scholar]