Abstract

Tobacco warning labels effectively educate consumers about the harms of tobacco and reduce smoking behavior. Lessons from tobacco warning labels can be applied to developing and implementing warning labels for sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs). Large pictorial rotating warnings are particularly effective. Dental professionals can be an important voice in countering the industry’s efforts to create controversy around the effects of SSBs and in advocating for effective warning labels based on the evidence from the tobacco warning labels.

Sugar, rum and tobacco are commodities which are nowhere necessaries of life, which are become objects of almost universal consumption and which are therefore extremely proper subjects of taxation.1

The similarities between “sugar, rum and tobacco” do not end with them being unneeded yet ubiquitous consumer products and good candidates for taxes, as Adam Smith pointed out almost two and a half centuries ago. Since then, we learned that sugar, alcohol and tobacco are also detrimental to health. Alcohol, and particularly tobacco, have become subjects of additional regulations, such as restrictions on advertisements and sales and health warnings. More recently, the public health and medical communities have been calling for regulating added sugars in a similar way.2 Consumption of added sugars has been linked to the development of dental caries,3–5 obesity,6–8 diabetes,9 fatty liver disease10 and cardiovascular disease.11,12 Sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) are the leading source of added sugars in the diet.13 SSBs are beverages to which sugar or other caloric sweetener has been added. Examples of SSBs are soft drinks, fruit drinks, sports drinks, tea and coffee drinks and energy drinks.14 Sometimes sweetened milk products are included in the SSB category as well, but with the caveat that unlike other SSBs, milk contains protein and other nutrients.14 SSBs typically do not comprise 100 percent fruit juice.

Consumption of SSBs is greater among African-Americans and Mexican-Americans than among Caucasians for both men and women and across most age groups.15–17 Consumption is also greater among low-income and low-education groups.18 These are the same groups that have higher rates of obesity, diabetes and other diseases.19–22

Lessons learned from tobacco control are applicable to developing and promoting policies around added sugars. Public health advocates, including dental professionals, could use the tools, strategies and policies of tobacco control to reduce the negative impact of added sugars on population health. One such policy is warning labels on sugar-sweetened beverages. This article provides an overview of what we know about tobacco warning labels, what types of labels are particularly effective and how these lessons can be translated to SSB warning labels policymaking.

History of Tobacco Warning Labels

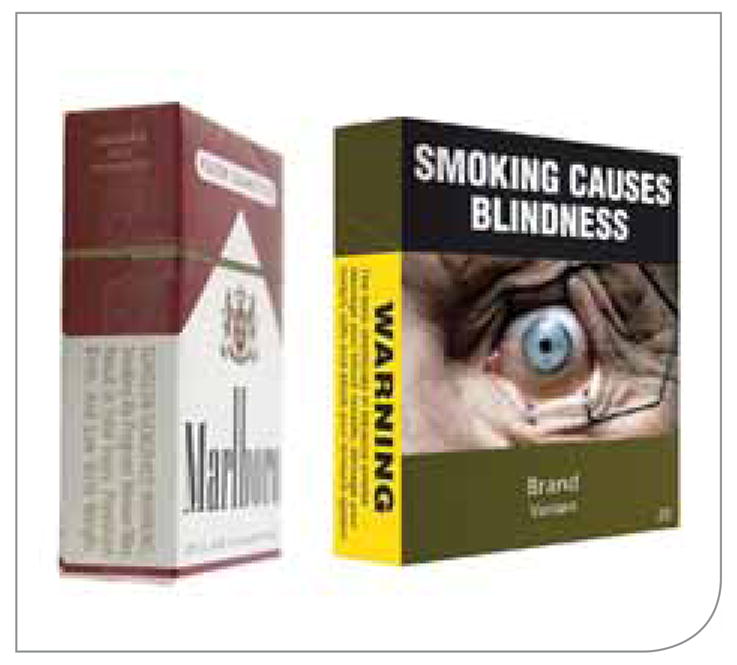

The U.S. was the first country in the world to require a health warning on cigarette packages. This earliest warning label appeared in 1966 on the side of cigarette packs and read, “Caution: Cigarette Smoking May Be Hazardous to Your Health.” U.S. labels were updated slightly over the years to change the copy, but remained in the same place — the side of the package. Although Congress authorized the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2009 to develop and implement new pictorial warning labels, the first set of warning labels was struck down in court and today cigarette packs still carry the same four labels first introduced in 1985 (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1.

Examples of cigarette warning labels in the U.S. (left) and Australia (right).

The rest of the world moved on. Driven by the motivation to make warnings more effective, written warnings became more specific, explicitly mentioning diseases caused by smoking, such as lung cancer and heart attack, as Iceland first did in 1969.23 Warnings moved from the side of the packs to the front and the back of the pack (first in Saudi Arabia in 1987) and grew larger — covering 30 percent, 50 percent, 80 percent and even 90 percent of the pack, as Nepal did in 2015. Pictures illustrating the health effects of smoking appeared in Iceland first in 1985.23 Finally, the brand colors and logos were removed from the packs and replaced with a drab olive color, pioneered by Australia in 2012 (FIGURE 1).

Previously secret internal tobacco industry documents chronicle the history of the tobacco industry’s resistance to the implementation of warning labels and reveal that tobacco companies made it their policy to “avoid health warnings on all tobacco products for just as long as we can”24 because of their potential effectiveness. These internal tobacco industry documents are housed in the University of California, San Francisco, Truth (formerly Legacy) Tobacco Industry Documents Library. This library contains more than 80 million documents and is available as a free online resource, industrydocuments.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco, to researchers all over the world.

Sen. Wallace Bennett (R-Utah) put forth the first proposal for a warning label on cigarettes in 1957.25 It read, “Warning, prolonged use of this product may result in cancer, in lung, heart and circulatory ailments and in other diseases.”26 However, the legislation didn’t pass until eight years later, and then in a much weaker form, as described above. The first pictorial warning label was proposed to be on state cigarette tax stamps in South Dakota in 1959 by Sen. Donald Stransky, who was a heavy smoker himself.27 The picture would feature skull and crossbones with the words “The use of this product is not recommended by the State of South Dakota. The use thereof may result in cancer or heart disease.”28 The bill passed in the South Dakota Senate by a small majority. The tobacco industry mobilized tobacco distributors, agricultural and business groups and others.29 A governor of North Carolina, a tobacco-growing state, threatened to retaliate by labeling the farm products from South Dakota as coming from the soil with the “highest content in the nation of selenium, a well-known poison.”27 Newspapers in other tobacco-growing states, such as West Virginia, asked whether bread, butter and meat produced in South Dakota and linked to obesity and heart disease should be labeled with skull and crossbones as well.30 The bill was defeated in the House.31

Following South Dakota, between 1959 and 1961, Utah and New York proposed skull and crossbones labels, while Massachusetts and Missouri proposed textual health warnings.31 None of these legislative proposals passed.

As the momentum of the legislative proposals demanding warnings on cigarettes and continued accumulation of scientific evidence linking smoking and disease made warnings inevitable, tobacco companies were determined to influence the content of these warnings to minimize their effectiveness, saying, “it has been our policy to resist any mention of specific diseases.”24 The first U.S. cigarette warning label, “Caution: Cigarette Smoking May Be Hazardous to Your Health” was originally proposed by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) as, “Caution: Cigarette Smoking Is Dangerous to Health. It May Cause Death From Cancer and Other Diseases.”32 The tobacco industry succeeded not only in curtailing the wording of this health warning but also in postponing its implementation date and in prohibiting (preempting) any local or state governments from passing any laws related to warnings on cigarette packaging or advertising.33 The passage of this law (Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act of 1965) was called by The Atlantic, “The Quiet Victory of the Cigarette Lobby: How It Found the Best Filter Yet — Congress.”34

Tobacco companies also worked to “always to have warning clauses attributed to an appropriate government authority.”24 This allowed tobacco companies to continue to dispute the claims about the harmful effects of tobacco. Because the government was the source of the warnings, the tobacco companies could disassociate themselves from these warnings and continue to argue that tobacco was not that harmful and continue to confuse smokers, despite conclusive scientific evidence.24

The warning created by this act and later weak warnings were successfully used by the tobacco companies to seek immunity from litigation in state and federal jurisdictions35,36 and then in the Supreme Court.37 They argued that the federally mandated warning label was sufficient for consumers to be fully informed about the risks of smoking.

Most recently, tobacco companies sued the FDA when it required nine new pictorial warning labels to cover 50 percent of the front and back of cigarette packs and 20 percent of advertisements.38 The tobacco companies claimed that these labels unjustifiably and inappropriately violated their First Amendment rights by compelling them to disseminate anti-tobacco messages for the government. Two different challenges were brought up and the courts used somewhat different standards for constitutional review resulting in different outcomes, but ultimately, the divided United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit ruled the proposed pictorial warning labels as written to be in violation of the tobacco companies’ constitutional right to freedom of speech.39 A detailed discussion of the different levels of scrutiny and the court’s decision making is available elsewhere.40,41 In brief, the court ruled that the government did not provide sufficient evidence that the proposed warning labels would lower smoking rates. The FDA chose not to appeal to the Supreme Court; instead, it revoked its pictorial warning regulation but promised to continue research and develop new warning labels.42 As of June 2016, the FDA had not announced any further regulatory developments regarding pictorial warning labels on cigarettes.

While tobacco companies oppose warning labels, consumers actually support them. A national survey in Brazil showed that 76 percent approved of pictorial warning labels, including 73 percent of smokers.43 In the U.S., the majority of residents supported the introduction of pictorial warning labels between 2007 and 2012, although after the specific labels were introduced by the FDA in 2011 the support among current smokers (those who reported smoking cigarettes in past 30 days) declined from 62 percent in 2011 to 40 percent in 2012.44 People consider warning labels effective in dissuading themselves or other smokers from smoking and pictorial warning labels were perceived as more effective than text.45

Research on Tobacco Warning Labels

After the implementation of the first warning labels in 1966, the FTC’s 1981 report concluded that the original warning labels were not novel, overexposed and too abstract to remember and be personally relevant.46 Warning labels, like advertisements, wear out over time.47 Written warning labels wear out faster than graphic ones.48,49 In response, Congress passed a law mandating four rotating warnings. Studies on them began appearing in the late 1980s, demonstrating that several years after the implementation, those written labels on cigarette packs were also not noticed and not remembered by smokers and adolescents.50–53 Since then, the diffusion and evolution of tobacco warning labels have been propelled by observational and experimental studies showing the effectiveness of large graphic warning labels in informing consumers about the health harms of smoking and reducing their smoking behavior.45,54

Warning labels are noticed, read and remembered

Both smokers and nonsmokers notice warning labels on cigarettes and recall their content.54 For example, in an Australian study, among the new written warning labels, the most frequently recalled were “Smoking kills” and “Smoking in pregnancy harms your baby.”55 A meta-analysis of experimental studies showed that pictorial warning labels attract attention and keep it longer than written warning labels, but that the differences in recalling the content of the warning labels were not significant between written and pictorial labels.45 Another study showed that graphic warning labels on tobacco advertisements, compared to small copy-only warnings capture attention quicker and hold it longer, resulting in better recall of the warning’s message.56

Warning labels increase knowledge of the risks of smoking

Noticing warning labels is related to a greater knowledge of health risks of smoking.57 In countries where a specific disease (such as stroke) was mentioned on health warnings, more people had the knowledge that smoking causes this particular disease than in countries without health warnings concerning this disease.57,58 After new written warning labels were introduced in Australia, smokers increased their knowledge of the harmful constituents of smoke.55

Warning labels make smokers think about quitting

In countries with pictorial or large (50 percent of the pack) written warning labels, more smokers report that labels led them to think about stopping smoking.59 For example, 57 percent of Australian smokers said that warning labels motivated them to think about quitting smoking.60

Warning labels make smokers quit smoking and prevent nonsmokers from starting to smoke

Evidence from countries after the introduction or changes in warning labels indicate that these changes are related to reduced numbers of cigarettes smoked and fewer smokers.54 A recent systematic review found that implementation of strengthened warnings (i.e., a switch from copy-only to graphic warning) was associated with increased quit attempts and short-term smoking cessation and decreased smoking prevalence in those countries.61 However, in observational population-level studies it is difficult to determine unique causal effects of warning labels when they are implemented along with other policies, such as smoke-free laws. Nonetheless, a quasi-experimental study parsing out the effects of other policies estimated that implementation of graphic warning labels in Canada reduced smoking rates by 2.87 to 4.68 percentage points.62 In addition, a recent randomized clinical trial demonstrated that smokers whose packs had large graphic warning labels were more likely to attempt to quit smoking during the four-week clinical trial than smokers with copy-only warnings (40 percent versus 34 percent, or 1.29).63

History of Warning Labels on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages

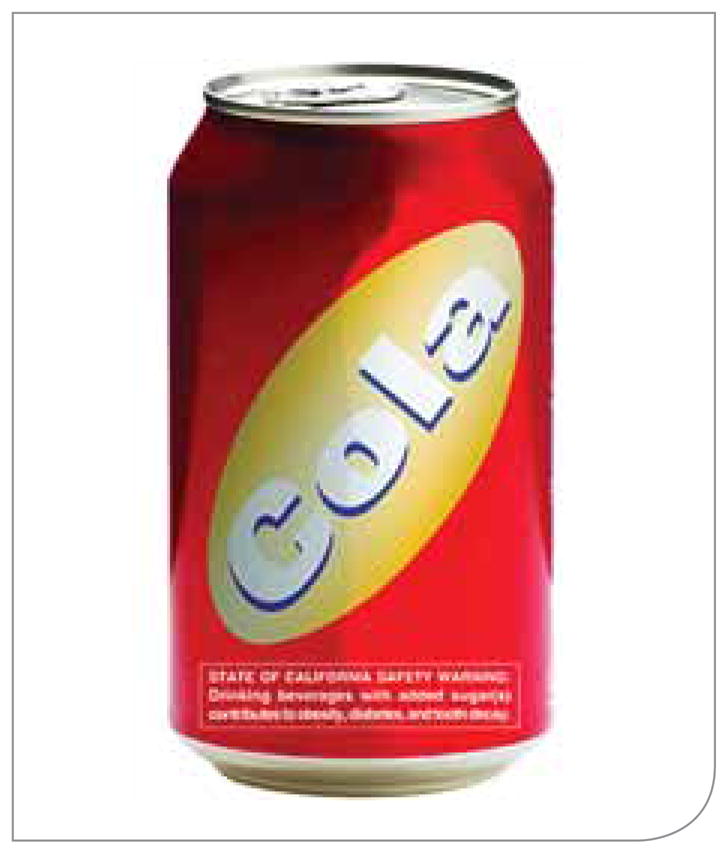

As of April 2016, no health warnings on SSBs have been implemented. However, there is support for this measure. In California, 78 percent of registered voters support requiring text warning labels on soda or other sugary drinks.64 There have been some attempts to pass laws requiring warning labels on SSBs. In February 2012, a bill was introduced in California that would require SSBs to carry a warning: “STATE OF CALIFORNIA SAFETY WARNING: Drinking beverages with added sugar(s) contributes to obesity, diabetes and tooth decay”65 (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 2.

California proposed warning labels on sugar-sweetened beverages. (Source: Public Health Advocates, kickthecan.info/soda-warning-labels.)

However, this bill was held in committee and did not advance. Another attempt to implement this warning label was undertaken in 2015, but likewise did not pass the committee.66 The beverage industry opposed these bills and lobbied the legislators to make sure they did not advance.67,68 The California Dental Association lent its support to both bills.69,70 Similar bills have been proposed in New York state,71 Hawaii, Vermont and Washington,72 but as of July 2016 these bills had not yet been passed into laws.

San Francisco passed a law in 2015 requiring advertisements for SSBs displayed on billboards, buses, transit shelters, posters and stadiums within the city to carry a warning: “WARNING: Drinking beverages with added sugar(s) contributes to obesity, diabetes and tooth decay. This is a message from the City and County of San Francisco.”73 Baltimore City Council has been considering requiring warning signs in businesses that sell sugar-sweetened beverages.74

Just as tobacco companies resisted warning labels on cigarettes, the food and beverage industry is fighting the implementation of warning labels on SSBs. Newly discovered sugar industry documents reveal that the cane and beet sugar industries have actually been working to resist regulation of sugars, including warning labels, since the 1970s.75,76 Their main tactic was to influence research agenda of the national agencies (such as the National Caries Program) and produce their own research that would point at causes other than sugar for health issues such as dental caries.77 More recently, the American Beverage Association argued that warning labels on SSBs are misleading, that SSBs are not uniquely harmful to health and that singling them out is unfair and will not improve public health.78 They claim that the solution to the obesity and diabetes crises lies not in demonizing the SSBs but in educating people on balancing calories consumed and calories spent through exercise.79 During the hearing on the warning labels ordinance in San Francisco, the American Beverage Association brought in a dietician from Washington, D.C.,80 to repeat this argument.81 After the San Francisco Board of Supervisors unanimously passed the ordinance requiring warning labels on advertisements for SSBs, the American Beverage Association, the California Retailers Association and the California State Outdoor Advertising Association sued the city of San Francisco.82 Their motion for preliminary injunction that would have prevented the ordinance from taking effect was denied by the U.S. district judge on May 17, 2016. Expert testimony countering industry claims, including the evidence linking SSBs to health effects (such as dental caries) as well as evidence of the effectiveness of tobacco warning labels, played an important role in the judge’s decision.83 On June 8, 2016, however, the same judge granted a shorter-term injunction that would prevent the ordinance from going into effect until his previous ruling is reviewed in the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.84

Research on SSB Warning Labels

Some research is emerging evaluating reactions to and short-term effects of textual warnings on SSBs. A study evaluated the effects of different versions of a California warning label (“SAFETY WARNING: Drinking beverages with added sugar(s) contributes to obesity, diabetes and tooth decay”) on parents of 6- to 11-year-old children in an online experiment.85 Labels differed in that one used “weight gain” instead of “obesity,” another added “preventable diseases” in front of the disease names and another added “type 2 diabetes” to the list of diseases. Parents who saw any of these labels (compared to parents who saw a beverage with no label or with the American Beverage Association’s “Clear on Calories” label that depicted the number of calories) believed that SSBs were less healthy for their child and were significantly less likely to select an SSB for their child from an online vending machine. The variations in the wording of the warning label (e.g., “weight gain” versus “obesity”) did not have a significant effect on the parents’ perceptions or hypothetical purchasing behavior.

What Should Warning Labels on Soda Look Like?

Lessons from tobacco warning labels can be applied to SSBs to make these labels more effective. The World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC)86 provides specific guidance. Adopted in 2003, the FCTC was the world’s first global public health treaty, and it was signed by 168 countries (the U.S. was not one of them). Article 11 of the FCTC could be used to guide the design of the SSB warning labels according to the recommendations for tobacco warning labels that were developed based on empirical evidence. For example, a warning label should cover no less than 30 percent (preferably 50 percent) of the primary display area of a package. Warning labels should be rotated frequently to keep them novel. They should appear on the package and on advertisements. Ideally, a picture should accompany the written warning to make the message more salient and to communicate the message for those with low literacy. All of the currently proposed warning labels for SSBs fall short of the FCTC recommendations.

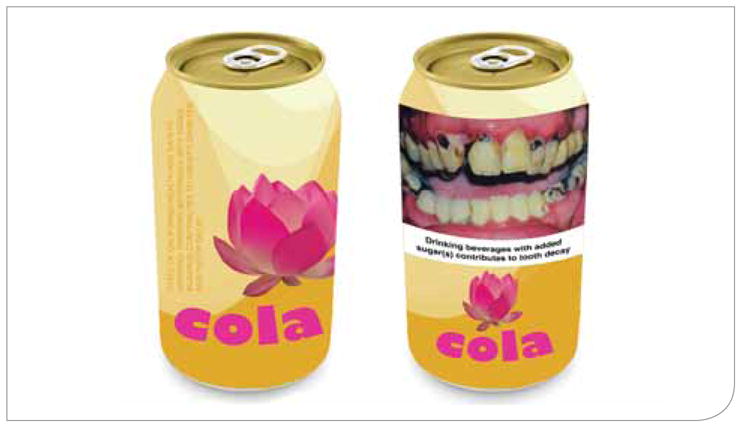

Two examples of SSB warning labels are presented in FIGURE 3. The soda can on the left features a warning label similar to the current U.S. alcohol and tobacco warning labels. The label is positioned vertically, while the main product copy is horizontal. The use of all capital letters and a text color that blends in with the background may also make this label less effective.87

FIGURE 3.

Examples of potentially ineffective and effective warning labels for soda. (Source: flickr.com/photos/figgenhoffer/3661358131.)

In contrast, the soda can on the right has a prominent pictorial warning label that could be more effective. The image covers 50 percent of the front surface, which makes it easier to see and attract attention.45,86 The copy and the picture focus on one specific disease (tooth decay), but this would be part of the set of rotating pictorial warnings with other labels focusing on obesity and diabetes. Tobacco companies extensively researched visual elements for cigarette packs to make them more eye-catching.87,88 They found that a white background, high-color saturation and high contrast made the design elements stand out. Yellow was the most noticeable and memorable color, but consumers did not perceive it as pleasant, associating it with stress and anxiety. Based on the findings from tobacco industry research, to increase visible prominence of labels, black copy on a yellow background could be used. The warning does not contain attribution to the government source. Attribution to a government authority allows the industry to continue to dispute the science about the harms of the products.

Knowing the history of the resistance of tobacco companies to warning labels and the incipient resistance from the beverage and sugar industries, putting warning labels on sugar-sweetened beverages will not be an easy public health task. It would be helpful for advocates to review the arguments the tobacco industry used to avoid, delay and curtail warning labels,24 as well as other strategies of tobacco companies35 and other industries.2 There are useful summaries available for the arguments that are commonly used by the tobacco industry to combat warning labels and the ways to counter them.89 Similar resources are now available for advocates promoting regulation and labeling for SSBs.90 For example, the “slippery slope” argument might have contributed to the defeat of the early warning labels in the U.S. In Australia, when the ominous predictions of tobacco companies failed to materialize, this argument seemed to have lost its appeal.24 Tobacco control advocates should point out the fallacy in this argument that there is no evidence that putting warning labels on one product automatically leads to labeling other undesirable products.

When proposing warning labels for SSBs, whether textual or graphic, localities should work with legal counsel in order to pass judicial review. Among other things, advocates of warning labels on SSBs might need to demonstrate that the current advertising for SSBs is deceptive and needs to be corrected, propose labels that are based on facts and are not unjustifiably burdensome or too broad and convince the court that warning labels would advance a government’s substantial goal (such as reduce the rates of obesity, diabetes and other diseases or inform consumers about the harmful effects of SSBs).

When choosing whether to pursue warnings on products, advertisements or other locations (such as point of sale), advocates should consider several issues. It might be easier politically to require warning labels on advertisements because making separate packages for different localities or states might be seen as too burdensome to the manufacturers or distributors. Legally, they should consider if their proposed warning labels might be preempted by the federal Nutrition Labeling and Education Act (NLEA), which gives the FDA the authority to regulate food labeling.91

Conclusion

Health warnings on tobacco products have been an effective tool for educating consumers about the health risks of tobacco. Warning labels are just one of the tobacco control policies that are applicable to SSBs. Other policies include mass media campaigns, taxes and restrictions on marketing and sales, among others.2,92,93 Dental professionals are already educating their patients about this and other health issues, such as smokeless tobacco. The California Dental Association94 and the American Dental Association95 provide online, printable handouts that dental professionals can use to educate their patients about a variety of dental issues, including the role of sugar. But dental professionals should not only educate their patients. Health advocates, including dentists, should familiarize themselves with the history of the tobacco warning labels, the industry’s tactics to resist warning label regulations and the research on the effectiveness of warning labels. The industry will continue to challenge the science on health effects of SSBs and any efforts to put warning labels, including challenging the content and design of the labels. Dentists can lend support to policymakers to resist these challenges. Testifying in front of local city councils and writing or calling state representatives or writing editorials to local newspapers96 are just some of the ways to do this.

Future proposals for SSB warning labels should base the design, content, size and copy versus graphics on the evidence from tobacco research. More research on the effectiveness of SSB warning labels with the stronger design (such as the one suggested in this paper) should be conducted to preempt further industry challenges.

Lessons from the tobacco warning labels indicate SSB warning labels would not be easy to implement, but by combining emerging scientific evidence with public support and outreach of health professionals, this policy might be able to move forward and be another important tool to promote making informed decisions for healthier food choices.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (K99CA187460). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Biography

Lucy Popova, PhD, is a tobacco control researcher at The Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education at the University of California, San Francisco. She is studying how we can better communicate about the harms of tobacco and other products.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Disclosure: None reported.

References

- 1.Smith A. An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. p. 1776. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nestle M, Bittman M. Soda Politics: Taking on Big Soda (and Winning) Oxford University Press; USA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moynihan P, Kelly S. Effect on caries of restricting sugars intake systematic review to inform WHO guidelines. J Dent Res. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0022034513508954. 0022034513508954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheiham A, James W. Diet and dental caries the pivotal role of free sugars reemphasized. J Dent Res. 2015;94(10):1341–1347. doi: 10.1177/0022034515590377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernabé E, Vehkalahti M, Sheiham A, Lundqvist A, Suominen A. The Shape of the Dose-Response Relationship Between Sugars and Caries in Adults. J Dent Res. 2016;95(2):167–172. doi: 10.1177/0022034515616572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woodward-Lopez G, Kao J, Ritchie L. To what extent have sweetened beverages contributed to the obesity epidemic? Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(03):499–509. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010002375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: A systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(2):274–288. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pereira M. The possible role of sugar-sweetened beverages in obesity etiology: A review of the evidence. Int J Obes. 2006;30:S28–S36. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson RJ, Perez-Pozo SE, Sautin YY, et al. Hypothesis: Could excessive fructose intake and uric acid cause type 2 diabetes? Endocr Rev. 2009;30(1):96–116. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim JS, Mietus-Snyder M, Valente A, Schwarz J-M, Lustig RH. The role of fructose in the pathogenesis of NAFLD and the metabolic syndrome. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7(5):251–264. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lustig RH, Schmidt LA, Brindis CD. Public health: The toxic truth about sugar. Nature. 2012;482(7383):27–29. doi: 10.1038/482027a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang Q, Zhang Z, Gregg EW, Flanders WD, Merritt R, Hu FB. Added sugar intake and cardiovascular diseases mortality among U.S. adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):516–524. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Dietary sources of energy, solid fats and added sugars among children and adolescents in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(10):1477–1484. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC guide to strategies for reducing the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages. 2010 www.cdph.ca.gov/SiteCollectionDocuments/StratstoReduce_Sugar_Sweetened_Bevs.pdf.

- 15.United States Department of Agriculture. [Accessed July 15, 2016];Materials From the Sixth Meeting of the 2010 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, Additional Resources, Charts and Tables: Energy From Sugar-Sweetened Beverages. 2010 origin.www.cnpp.usda.gov/DGAs2010-Meeting6.htm.

- 16.Kumanyika S, Grier S, Lancaster K, Lassiter V. Impact of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption on Black Americans’ health. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taveras EM, Gillman MW, Kleinman K, Rich-Edwards JW, Rifas-Shiman SL. Racial/ethnic differences in early-life risk factors for childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):686– 695. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han E, Powell LM. Consumption patterns of sugar-sweetened beverages in the United States. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(1):43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among U.S. adults, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):491– 497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among U.S. children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):483– 490. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Williams DR, Pamuk E. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: What the patterns tell us. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S186–S196. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.166082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter JS, Pugh JA, Monterrosa A. Non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in minorities in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125(3):221–232. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-3-199608010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hiilamo H, Crosbie E, Glantz SA. The evolution of health warning labels on cigarette packs: The role of precedents, and tobacco industry strategies to block diffusion. Tob Control. 2014;23(1):e2–e2. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chapman S, Carter S. “Avoid health warnings on all tobacco products for just as long as we can:” A history of Australian tobacco industry efforts to avoid, delay and dilute health warnings on cigarettes. Tob Control. 2003;12(suppl 3):iii13–iii22. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_3.iii13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. [Accessed April 4, 2016];Cigarette smoking and health and related legislation. 1970 industrydocuments.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/xlhw0098.

- 26.Solon urges cigarette labels. Deseret News. 1965 Jan 30; news.google.com/newspapers?nid=336&dat=19650130&id=a6pSAAAAIBAJ&sjid=138DAAAAIBAJ&pg=4560,5742749&hl=en, 363.

- 27.Newsweek. [Accessed April 4, 2016];Cigarettes: One man’s meat. 1959 industrydocuments.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/ - id=yrgm0137.

- 28.The Tobacco Institute I. [Accessed April 4, 2016];We have just been informed that the UPI wire carried a story on the introduction. 1959 industrydocuments.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/ - id=hhgc0086.

- 29.Hill F, Knowlton C. [Accessed April 4, 2016];Hill and Knowlton’s Recommendations to the Tobacco Institute. 1959 industrydocuments.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/ - id=xyxp0146.

- 30.Williamson News. [Accessed April 4, 2016];Skull and crossbones. 1959 industrydocuments.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/ - id=lrgm0137.

- 31. [Accessed April 4, 2016];Summary of state labelling legislation. 1959 industrydocuments.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/ - id=gymh0045.

- 32.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing tobacco use among young people: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed March 23, 2016];Selected Actions of the U.S. Government Regarding the Regulation of Tobacco Sales, Marketing and Use (excluding laws pertaining to agriculture or excise tax) 2012 www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/by_topic/policy/legislation.

- 34.Drew E. The Quiet Victory of the Cigarette Lobby: How It Found the Best Filter Yet — Congress. The Atlantic Monthly. 1965;216:76–80. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arno PS, Brandt AM, Gostin LO, Morgan J. Tobacco industry strategies to oppose federal regulation. JAMA. 1996;275(16):1258–1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gostin LO, Brandt AM, Cleary PD. Tobacco liability and public health policy. JAMA. 1991;266(22):3178–3182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cipollone v Liggett Group, 505 US 504,112 SCt 2608, 2621, (1992).

- 38.R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. FDA, (D.D.C. 2011).

- 39.R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. FDA, 696 F.3d 1205 (D.C. Cir. 2012).

- 40.Consortium TCL. FDA Tobacco Project. 2015. Cigarette Graphic Warnings and the Divided Federal Courts; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kraemer JD, Baig SA. Analysis of legal and scientific issues in court challenges to graphic tobacco warnings. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(3):334–342. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holder EH., Jr Eric H. Holder Jr. to John Boehner. 2013 Mar 15; http://www.mainjustice.com/files/2013/03/Ltr-to-Speaker-re-Reynolds-v-FDA.pdf.

- 43.Cavalcante TM. Labelling and packaging in Brazil. Ginebra, Suiza: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kamyab K, Nonnemaker JM, Farrelly MC. Public support for graphic health warning labels in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(1):89–92. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Noar SM, Hall MG, Francis DB, Ribisl KM, Pepper JK, Brewer NT. Pictorial cigarette pack warnings: A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Tob Control. 2015 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051978. tobaccocontrol-2014-051978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Myers M, Iscoe C, Jennings C, Lenox W, Minsky E, Sachs A. Federal Trade Commission staff report on the cigarette advertising investigation. Division of Advertising Practices, Federal Trade Commission; May, 1981. public version. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blair MH. An empirical investigation of advertising wearin and wearout. J Advertising Res. 2000;40(06):95– 100. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Borland R, Wilson N, Fong GT, et al. Impact of graphic and text warnings on cigarette packs: Findings from four countries over five years. Tob Control. 2009 Oct;18(5):358–364. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.028043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yong H-H, Fong GT, Driezen P, et al. Adult smokers’ reactions to pictorial health warning labels on cigarette packs in Thailand and moderating effects of type of cigarette smoked: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Southeast Asia Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013:nts241. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Richardson P. ADM. Vol. 281. Silver Spring, Md: Macro Systems, Inc; 1987. Review of the Research Literature on the Effects of Health Warning Labels: A Report to the United States Congress; pp. 86–0003. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fischer PM, Richards JW, Berman EJ, Krugman DM. Recall and eye tracking study of adolescents viewing tobacco advertisements. JAMA. 1989;261(1):84–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davis RM, Kendrick JS. The Surgeon General’s Warnings in Outdoor Cigarette Advertising: Are They Readable? JAMA. 1989;261(1):90–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Richards JW, Fischer P, Conner FG. The warnings on cigarette packages are ineffective. JAMA. 1989;261(1):45–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.1989.03420010055025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hammond D. Health warning messages on tobacco products: A review. Tob Control. 2011;20:327–337. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.037630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Borland R, Hill D. Initial impact of the new Australian tobacco health warnings on knowledge and beliefs. Tob Control. 1997;6(4):317–325. doi: 10.1136/tc.6.4.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Strasser AA, Tang KZ, Romer D, Jepson C, Cappella JN. Graphic warning labels in cigarette advertisements: Recall and viewing patterns. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(1):41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hammond D, Fong GT, McNeill A, Borland R, Cummings KM. Effectiveness of cigarette warning labels in informing smokers about the risks of smoking: Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006 Jun;15(Suppl 3):iii19–25. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.012294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thrasher JF, Hammond D, Fong GT, Arillo-Santillán E. Smokers’ reactions to cigarette package warnings with graphic imagery and with only text: A comparison between Mexico and Canada. Salud publica de Mexico. 2007;49:s233–s240. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342007000800013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hammond D, Fong GT, Borland R, Cummings KM, McNeill A, Driezen P. Text and graphic warnings on cigarette packages: Findings from the international tobacco control four country study. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(3):202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shanahan P, Elliott D. Evaluation of the effectiveness of the graphic health warnings on tobacco product packaging 2008. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Noar SM, Francis DB, Bridges C, Sontag J, Ribisl KM, Brewer NT. The impact of strengthening cigarette pack warnings: Systematic review of longitudinal observational studies. Soc Sci Med. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang J, Chaloupka FJ, Fong GT. Cigarette graphic warning labels and smoking prevalence in Canada: A critical examination and reformulation of the FDA regulatory impact analysis. Tob Control. 2014;23(suppl 1):i7–i12. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brewer NT, Hall MG, Noar SM, et al. Effect of Pictorial Cigarette Pack Warnings on Changes in Smoking Behavior: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Field Research Corporation. Voters see a close linkage between kids regularly drinking sugary beverages and their developing serious health conditions, like type 2 diabetes. [Accessed March 23, 2016];Broad-based support for both government and beverage company actions to address the problem. 2016 www.field.com/fieldpollonline/subscribers/Rls2529.pdf.

- 65. [Accessed April 4, 2016];SB-1000 Public health: Sugar-sweetened beverages: Safety warnings. leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billHistoryClient.xhtml?bill_id=201320140SB1000.

- 66. [Accessed April 4, 2016];SB-203 Sugar-sweetened beverages: Safety warnings. leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billHistoryClient.xhtml?bill_id=201520160SB203. [PubMed]

- 67.O’Hara J, Musicus A. Big Soda Versus Public Health. 2015 cspinet.org/new/pdf/big-soda-vs-public-health-report.pdf.

- 68.Holt S. [Accessed July 15, 2016];California Soda Warning Label Bill Dies as Research Suggests Efficacy. 2016 civileats.com/2016/01/14/california-soda-warning-label-bill-dies-as-research-suggests-efficacy.

- 69. [Accessed April 4, 2016];Bill Analysis: SB 1000. www.leginfo.ca.gov/pub/13-14/bill/sen/sb_0951-1000/sb_1000_cfa_20140528_131714_sen_floor.html.

- 70. [Accessed April 4, 2016];Fact Sheet: SB 203. www.lchc.org/wp-content/uploads/SB-203-SSB-Safety-Warning-Act-fact-sheet-3-9-15.pdf.

- 71. [Accessed April 4, 2016];New York State Assembly: Bill No. A02320. assembly.state.ny.us/leg/?default_fld=&bn=A02320&term=2015&Summary=Y&Actions=Y&Text=Y&Votes=Y.

- 72.Kick the Can. [Accessed April 4, 2016];Legislative campaigns. www.kickthecan.info/legislative-campaigns.

- 73. [Accessed April 4, 2016];Sugar-sweetened beverage warning for advertisements. Ordinance No. 100-15. Article 42, Division 1 Sections 4200-06: Sugar sweetened beverage warning ordinance. www.sfbos.org/ftp/uploadedfiles/bdsupvrs/ordinances15/o0100-15.pdf.

- 74.Cohn M. Baltimore officials want warnings on sugary drinks. Baltimore Sun. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kearns CE, Glantz SA, Schmidt LA. Sugar industry influence on the scientific agenda of the National Institute of Dental Research’s 1971 National Caries Program: A historical analysis of internal documents. PLoS Med. 2015;12(3):e1001798. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Taubes G, Couzens CK. Big sugar’s sweet little lies. Mother Jones. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 77.The Sugar Association. [Accessed July 11, 2016];The Sugar Association calls for withdrawal of ‘added sugars’ labeling proposal in comments filed to FDA. 2014 www.sugar.org/sugar-association-calls-withdrawal-added-sugars-labeling-proposal-comments-filed-fda.

- 78.American Beverage Association. [Accessed April 4, 2016];Misleading Warning Labels Won’t Improve Public Health. 2015 www.ameribev.org/blog/2015/02/misleading-warning-labels-wont-improve-public-health.

- 79.American Beverage Association. [Accessed April 4, 2016];Warning labels won’t work. 2015 www.ameribev.org/blog/2015/03/warning-labels-won%E2%80%99t-work.

- 80.GMO Answers. [Accessed April 4, 2016];Independent Expert Lisa D. Katic RD. gmoanswers.com/experts/lisa-d-katic-rd.

- 81.CBS SF Bay Area. [Accessed April 4, 2016];San Francisco Board of Supervisors Approve Health Warnings for Sugary Beverage Ads. 2015 sanfrancisco.cbslocal.com/2015/06/09/san-francisco-board-of-supervisors-approve-health-warnings-for-sugary-beverage-ads.

- 82.American Beverage Association et al. v City and County of San Francisco, 3:15-cv-03415. www.khlaw.com/webfiles/SF sugar warning lawsuit.pdf.

- 83.Shape Up San Francisco. [Accessed July 15, 2016];Lawsuit against warnings for SSB advertisements. 2016 shapeupsfcoalition.org/resources/heal-legislation/ssblawsuitinfo.

- 84.Egelko B. [Accessed June 8, 2016];SF’s soda advertising law on hold as industry appeals in court. 2016 www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/SF-s-soda-advertising-law-on-hold-as-industry-7971253.php.

- 85.Roberto CA, Wong D, Musicus A, Hammond D. The Influence of Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Health Warning Labels on Parents’ Choices. Pediatrics. 2016:2015–3185. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3185. peds. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Elaboration of guidelines for implementation of Article 11 of the Convention. 2008 apps.who.int/gb/fctc/PDF/cop3/FCTC_COP3_7-en.pdf.

- 87.Lempert LK, Glantz S. Packaging colour research by tobacco companies: The pack as a product characteristic. Tob Control. 2016 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052656. tobaccocontrol-2015-052656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 88.Lempert LK, Glantz SA. Implications of tobacco industry research on packaging colors for designing health warning labels. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016:ntw127. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. Warning labels: Countering industry arguments. 2011 global. tobaccofreekids.org/files/pdfs/en/WL_industry_arguments_en.pdf.

- 90.Public Health Advocates. [Accessed July 15, 2016];Kick the Can: Giving the boot to sugary drinks. www.kickthecan.info.

- 91.ChangeLab Solutions, National Policy & Legal Analysis Network to Prevent Childhood Obesity (nplan) [Accessed July 11, 2016];Model Legislation Requiring a Safety Warning for Sugar-Sweetened Beverages. 2014 www.changelabsolutions.org/publications/SSB-safety-warnings.

- 92.Ontario Medical Association. Applying lessons learned from anti-tobacco campaigns to the prevention of obesity. Ont Med Rev. 2012;(October):12–15. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pomeranz JL. Advanced policy options to regulate sugar-sweetened beverages to support public health. J Public Health Policy. 2012;33(1):75–88. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2011.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.California Dental Association. [Accessed June 30, 2016];Patient fact sheets. www.cda.org/public-resources/patient-fact-sheets.

- 95.American Dental Association. Eating habits for a healthy smile and body. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141(12) doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2010.0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Glassman G. [Accessed April 4, 2016];Legislature bows down to Big Soda. 2016 www.sacbee.com/opinion/op-ed/soapbox/article59364713.html.