Abstract

A recent gene expression classification of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) includes a poor survival subclass termed S2 representing about one third of all HCC in clinical series. S2 cells express E-cadherin, and c-myc and secrete AFP. As the expression of fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFRs) differs between S2 and non-S2 HCC, this study investigated whether molecular subclasses of HCC predict sensitivity to FGFR inhibition. S2 cell lines were significantly more sensitive (p<0.001) to the FGFR inhibitors BGJ398 and AZD4547. BGJ398 decreased MAPK signaling in S2 but not in non-S2 cell lines. All cell lines expressed FGFR1 and FGFR2, but only S2 cell lines expressed FGFR3 and FGFR4. FGFR4 siRNA decreased proliferation by 44% or more in all five S2 cell lines (p<0.05 for each cell line), a significantly greater decrease than seen with knockdown of FGFR1-3 with siRNA transfection. FGFR4 knockdown decreased MAPK signaling in S2 cell lines, but little effect was seen with knockdown of FGFR1-3. In conclusion, the S2 molecular subclass of HCC is sensitive to FGFR inhibition. FGFR4-MAPK signaling plays an important role in driving proliferation of a molecular subclass of HCC. This classification system may help identify those patients who are most likely to benefit from inhibition of this pathway.

Keywords: Liver Cancer, FGFR, MAPK, BGJ398, AZD4547

Introduction

Hepatocellular cancer (HCC) is the second leading cause of cancer death among men and the sixth leading cause of cancer death among women worldwide.1 The incidence of HCC in the United States has been increasing, possibly due to a rise in obesity and Hepatitis C infection.2 The multikinase inhibitor sorafenib is the first-line therapy for HCC not amenable to loco-regional therapy, extending median overall survival by two to three months.3 Gene expression signatures are clinically available to guide the management of cancers such as breast and colon,4-6 but no such assay is used in clinical practice for HCC. In investigatory studies, multigene signatures provide greater promise than single-gene based tests as both prognostic and predictive biomarkers, with the ultimate goal of personalizing cancer treatment.7

A HCC gene classification system that is highly reproducible between clinical sample sets, divides HCC into three major subclasses termed S1, S2 and S3.8 S1 tumors compose 28-31% and S2 tumors compose 23-24% of HCC in clinical data sets. Both S1 and S2 tumors are associated with a worse survival prognosis than S3 tumors. S1 tumors are more locally invasive, while S2 tumors express E-cadherin, Glypican-3 and c-myc and secrete alpha fetoprotein (AFP). This gene classification system has identified S1 and S2 HCC cell lines, but has never identified a S3 cell line, suggesting that cells of this type are unable to survive in vitro. Microarray analysis of human hepatoma cell lines has revealed similar subtypes with one group characterized by the activation of oncofetal promoters leading to increased expression of AFP and insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF-2) and the other characterized by overexpression of genes involved in metastasis and invasion, such as CD44.9 Features of these molecular categorization systems have predicted HCC response to emerging targeted therapies in preclinical studies as first reported by us, including inhibitors of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR),10 insulin-like growth factor receptor 1 (IGF-1R)11-12 and Src/Abl.13

Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and FGF receptor (FGFR) signaling abnormalities are increasingly identified in numerous human cancers.14 FGFR signaling primarily drives cancer cell proliferation through downstream effects on the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway.15 The first generation of FGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors are byproducts of the development of anti-angiogenic drugs.16-19 More recently, a second generation of compounds with less activity against vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2), and fewer hypertensive side effects was developed.20-21 This second generation is under clinical investigation for FGFR-amplified lung, breast, bladder and gastric cancer.22 FGFR4 is expressed in mature hepatocytes23 and plays a role in the regulation of bile acid synthesis in hepatocytes in response to endocrine signaling from the terminal ileum.24-25 FGFR4 signaling may contribute to hepatic carcinogenesis and could emerge as a therapeutic target for HCC.26-30

In this study we examine how FGFR1-4 are differentially expressed between S2 and non-S2 molecular subclasses of HCC, and how this expression pattern correlates with sensitivity to FGFR inhibitors. The S2 subclass of HCC cell lines express FGFR3 and FGFR4 and non-S2 cell lines do not. The S2 subclass of HCC is significantly more sensitive to pharmacologic inhibition of FGFR. Mechanistic investigations of both pharmacologic and genetic inhibition of FGFR inhibition suggest that the sensitivity of the S2 HCC subclass is mediated through FGFR4-MAPK signaling.

Materials and Methods

Statistics

GraphPad Prism 6.0 was used to perform non-linear regression to determine best-fit sigmoid curves of cell viability. The remainder of statistical tests were performed on Microsoft Excel 2003.

Cells and culture conditions

Human hepatoma cell lines SNU-398 and SNU-423 were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. The hepatoma cell lines SK-Hep, HepG2, and Hep3B were kindly provided by Barrie Bode (Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL), HuH-7 was provided by Jake Liang (National Institutes of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH, Bethesda, MD), and HuH-1, HLE and HLF were provided by Suguru Yamada (Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan). Cell lines were verified by DNA fingerprinting with small tandem repeat (STR) profiling. All the cell lines were propagated in DMEM (4.5 mg/mL glucose, 2 mmol/L l-glutamine) with 10% fetal bovine serum (both from MediaTech CellGro), supplemented with 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin (Life Technologies). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 in air. NVP-BGJ398 (Novartis) and AZD-4547 (AstraZeneca) were purchased from Selleck Chemicals. Stock solutions were prepared in DMSO and stored at −20°C (NVP-BGJ398) or −80°C (AZD-4547).

Real-time PCR

Human hepatoma cells were plated at 1 × 105/mL in 10mL of medium in a 100-mm plate and allowed to grow for 48 h to represent log-phase growth. Total RNA was extracted from each cell line with TRIzol (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions and subsequently treated with DNase I (Promega). Total RNA (250 ng) from each sample was used to create cDNA by single strand reverse transcription (SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix; Life Technologies). Expression of FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, FGFR4, FGF19 and beta-klotho (KLB) mRNA in the human hepatoma cell lines was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR using TaqMan gene expression assays (Life Technologies) on an Applied Bioscience 7900HT Fast Real Time PCR System using 96 well plates with a reaction volume of 20 μL according to the manufacturer’s instructions. mRNA relative quantification was calculated using the 2−ΔCT method normalizing to beta-actin. TaqMan Assay IDs are as follows: FGFR1, Hs00915142_m1; FGFR2, Hs01552915_m1; FGFR3, HS00179829_m1; FGFR4, Hs01106908_m1; FGF19, Hs00192780_m1; KLB, Hs00545621_m1; and beta-actin, Hs99999903_m1. All reactions were done in duplicate and the experiment was repeated to ensure reproducible results.

Western blotting

Cell lines were plated as described above. After 48 h, cells were incubated in fresh media for 30 mins with or without pharmacologic agents as indicated, after which the cells were washed in ice-cold PBS and harvested in 500 μL of radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (Boston BioProducts) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma). For FGF-19 experiments, cells were serum-starved overnight before treatment with 100 ng/ml FGF-19 for 30 mins. Protein concentration of lysates was analyzed by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method (Pierce Chemical Co.). Cellular lysates (40 μg) were prepared in Laemmli's reducing sample buffer (Boston BioProducts), separated by electrophoresis on 6% to 10% polyacrylamide gradient gels, and transferred electrophoretically onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore). Nonspecific binding on the membrane was blocked with TBS/0.1% Tween 20 (TBS/T) containing 5% powdered cow’s milk. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C and with appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP; GE Healthcare) for 1.5 hrs at room temperature. After each incubation period, membranes were washed thrice with TBS/T. Immunoreactive bands were visualized on X-ray film (Denville Scientific) with a chemiluminescent horseradish peroxidase (HRP) substrate (Perkin-Elmer). Relative levels of total and phosphorylated proteins were determined by western blot analysis with the following antibodies: FGFR1, FGFR3, FGFR4, c-myc, p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase [extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK)], phospho-ERK (Thr202/Tyr204) (all from Cell Signaling) and FGFR2 (Abcam). An antibody directed against β-actin (Abcam) was used to verify equal loading. Each western blot was repeated to ensure reproducible results. Western blots were quantified with image analysis software (Image J).

Cell growth assay

Briefly, cells were plated in triplicate at a density of 5 × 104/mL in a 24-well plate. After 24 h, medium containing inhibitors at the indicated concentrations or vehicle control was added. After 72 hours of drug exposure cell number was estimated by colorimetric 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay (MTT; Sigma). For FGF19 experiments, cells were treated in serum-free media with either 0, 0.1 or 10 ng/ml FGF-19 for 72 hours. The absorbance at 562 nm was measured with a spectrophotometric plate reader (Emax, Molecular Devices) and the experiment was repeated twice for each cell line. IC50 value was defined as the drug concentration yielding 50% nonsurviving cells compared with vehicle-treated controls.

Transfection of short interfering ribonucleic acid (siRNA)

Scrambled negative control siRNA (cat#4390843) and validated siRNA against FGFR1 (id-s5164), FGFR3 (id-s5168), and FGFR4 (id S5177 and 1412) were all obtained from Life Technologies (Silencer Select). Validated siRNA against FGFR2 (cat#S102665299) was obtained from Qiagen (FlexiTube). siRNA transfection was done according to the protocol supplied by Life Technologies. 1 × 105 cells were seeded into six-well plates, incubated overnight, then washed in cold PBS and changed to antibiotic free media immediately prior to transfection. Lipofectamine RNAiMax Reagent and 10 μM stock siRNA were dissolved in a 1:1 ratio in Opti-MEM Media, incubated for 5 minutes, and added to wells to achieve a final concentration of 30 nM siRNA. Cell lysates were collected and processed as above on post-transfection day 3 for qPCR and post-transfection day 4 for western blotting. This was repeated with cells plated in triplicate at a density of 2 × 104/mL in 24-well plates, with MTTs performed as above on post-transfection day 7 to assess cell growth.

Animal model

Six- to eight-week-old BALB/c nu−/nu− mice (Cox Laboratories, Massachusetts General Hospital) were maintained in accordance with the institutional guidelines of the Massachusetts General Hospital animal care facility. HuH-7 (S2 signature) and SK-Hep (non-S2 signature) were trypsinized and suspended in a 1:1 solution of 4°C PBS:Matrigel Matrix Solution (BD Biosciences) at a concentration of 5 × 106 living cells/100uL solution. Mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and 100uL of cell suspension was injected subcutaneously into the right flank. When tumors reached 100 mm3, mice were randomized to receive BGJ-398 (30mg/kg) in 100 μL of 0.5% methylcellulose daily by oral gavage, or 100 uL of 0.5% methylcellulose alone. Tumor volumes were measured every other day for 14 days using a calipers and the mathematical approximation of an ellipsoid: V = 0.52 × length × width × height. Mice were euthanized at the end of the study. Tumors were immediately bisected with half the tissue fixed in 10% formalin and half snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80C. Frozen portions of tumors were thawed, minced and sonicated in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (Boston BioProducts), before proceeding with western blotting as above.

Immunostaining

Formalin-fixed samples were embedded in paraffin, cut into 5 μm-thick sections and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H-E) according to standard procedures. Additional sections were stained with an antibody specific for Ki67 (BioLegend) by the MGH Histopathology Research Core. Ki67 positive cells were quantified with image processing software (ImageJ).

Results

Characterization of FGFR expression in molecular subtypes of human hepatoma cell lines

The S1, S2, and S3 gene signatures were previously derived from eight independent cohorts, totaling 603 patients, with diverse representation between common etiologic factors of HCC (alcohol, hepatitis B and C) and Eastern and Western countries, using three independent unsupervised clustering methods.8 A total of 9 human HCC cell lines were used in the current study. Five of these cell lines (Hep3B, HepG2, HuH-1, HuH-7, SNU-398) were positively enriched for the S2 gene signature (Supplementary Fig. 1). Four of these cell lines (HLE, HLF, SK-Hep, SNU-423) were negatively enriched for the S2 gene signature. Amplification of chromosomal region 11q13.3, (found in 15% of HCC) upregulates the FGFR4 ligand FGF19 and has been proposed as a genetic biomarker of sensitivity to anti-FGF19 therapies by Sawey et al.29 Two of the five (HuH-7 and Hep3B) cell lines in our panel of S2 enriched cell lines are known to harbor this amplification.

A microarray analysis had reported a difference in the expression of FGFR1-4 between similarly derived molecular subclasses of HCC cell lines, 9 and we observed overexpression of FGFR4 in the previously described human S2 subclass (Supplementary Fig. 2). We verified these observations by performing individual quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) characterizing the expression of FGFR1-4 in our panel of cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 3). S2 cell lines expressed significantly more FGFR3 and FGFR4 mRNA than non-S2 cell lines. On average, FGFR3 was over 100 fold more abundant, and FGFR4 was 28 times more abundant in S2 cell lines. No statistically significant difference between S2 and non-S2 cell lines was found regarding expression of FGFR1 or FGFR2. Across all nine cell lines, FGFR1 was approximately ten-fold more abundant at the mRNA level than FGFR2. An FGF19/FGFR4 autocrine loop has been proposed as an oncogenic driver in HCC.30 We characterized FGF19 in our panel and found that all S2 cell lines expressed FGF19 mRNA while FGF19 levels were below the limits of PCR amplification in all four non-S2 cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 4A). In addition to this difference between S2 and non-S2 cell lines, a dramatic range of expression of FGF19 was found in the S2 group with the highest expression (HuH-1) being over 300-fold greater than the lowest expression (SNU-398). Similarly, SNU-398 had the lowest expression of beta-klotho (KLB), the FGFR4 co-receptor (Supplementary Fig. 4B). Finally, while treatment with exogenous FGF19 activated MAPK signaling and increased cell proliferation in S2 cell lines, these effects were not observed in non-S2 cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 4C and Supplementary Fig. 5). Taken together, these data suggest that a functioning FGF19/FGFR4 autocrine loop is present in S2 cell lines.

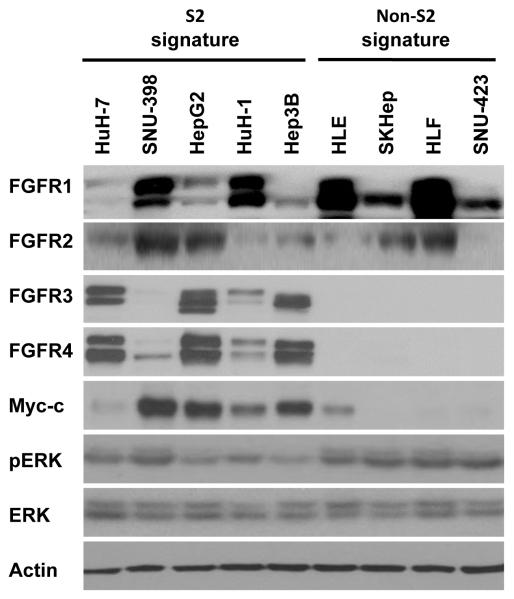

As predicted from the mRNA expression data all nine cell lines had detectable protein levels of FGFR1 and FGFR2 (Fig. 1). In addition, all five S2 cell lines had detectable levels of FGFR3 and FGFR4. In contrast, FGFR3 and FGFR4 were not detected in non-S2 cell lines. FGFR signaling is known to drive cellular proliferation via the MAPK pathway.15 We found phosphorylated ERK in all nine cell lines in our panel under normal culture media conditions. The S2 subclass of HCC is characterized by c-myc activation.8 We profiled our cell line panel and found that 4 of 5 S2 cell lines had readily detectable levels of c-myc protein, while in 3 of 4 non-S2 cell lines c-myc was completely undetected. This demonstrated that an important feature of the clinically derived S2 gene signature remained observable in cell lines.

Figure 1. Expression of FGFR protein in human HCC cell lines.

Protein expression of FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, FGFR4, c-myc, p-ERK, and total ERK was compared between S2 (HuH-7, SNU-398, HepG2, HuH-1, Hep3B) and non-S2 (HLE, SK-Hep, HLF, SNU-423) cell lines by western blot analysis. β-actin was assessed as a loading control.

Response of human hepatoma cell lines to pharmacologic FGFR inhibition

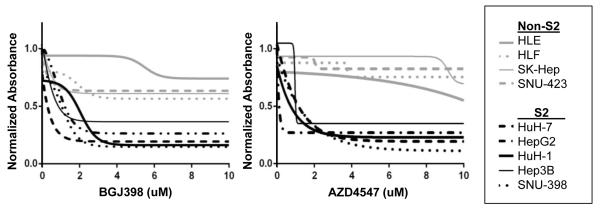

Multigene-expression based subclasses of HCC have previously correlated with preclinical response to targeted therapies.10-13 As expression of FGFR3 and FGFR4 is limited to the S2 HCC subclass, we hypothesized that sensitivity to FGFR inhibitors differs between the two subclasses. The S2 gene signature strongly correlated with susceptibility to the FGFR1-4 inhibitors BGJ398 and AZD-4547 as assessed by cell proliferation assays (Table 1). The S2 group had lower IC50 values, ranging from 0.15-2.73 μM for BGJ398 and 0.17-3.2 μM for AZD-4547. In contrast, the non-S2 group had higher IC50 values, ranging from 5.53 to above 10 μM for BGJ398 and 8.02 to above 10 μM for AZD-4547. This difference was statistically significant (p < 0.001 for both BGJ-398 and AZD-4547) when IC50s for the S2 group were compared to IC50s of the non-S2 group. On average, cell growth was inhibited at least two-fold more in S2 than in non-S2 cell lines at all doses tested above 1 μM of BGJ398 and AZD4547. Non-linear regression was performed to generate a best-fit sigmoidal curve representing dose dependent response for each cell line (Fig. 2).

Table 1. Effect of FGFR inhibition on HCC cell proliferation.

MTT drug sensitivity to BGJ398 and AZD-4547 in S2 (HuH-7, SNU-398, HepG2, HuH-1, Hep3B) and non-S2 (HLE, SK-Hep, HLF, SNU-423) cell lines.

| BGJ398 | AZD4547 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Signature |

Cell Line | IC50 (μM) |

Maximum Inhibition (10μM) |

IC50 (μM) |

Maximum Inhibition (10 μM) |

| S2 | HuH-7 | 0.15 | 89.3% | 0.17 | 80.0% |

| SNU-398 | 1.00 | 94.2% | 1.31 | 86.1% | |

| HepG2 | 1.52 | 92.4% | 3.2 | 72.1% | |

| HuH-1 | 2.73 | 93.1% | 1.19 | 79.0% | |

| Hep3B | 0.83 | 83.5% | 1.74 | 71.0% | |

| S1 | HLE | >10 | 35.1% | 8.02 | 58.8% |

| SK-Hep | 7.59 | 61.8% | 10 | 50.0% | |

| HLF | 7.93 | 53.8% | >10 | 36.5% | |

| SNU-423 | 5.53 | 85.7% | >10 | 39.8% | |

| t-test (S2 v S1 cell lines) | p<0.001 | p=0.013 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | |

Figure 2. Effect of FGFR inhibition of HCC cell proliferation.

Best-fit sigmoidal curves representing dose dependent response to BGJ398 and AZD-4547 in S2 (HuH-7, SNU-398, HepG2, HuH-1, Hep3B) and non-S2 (HLE, SK-Hep, HLF, SNU-423) cell lines.

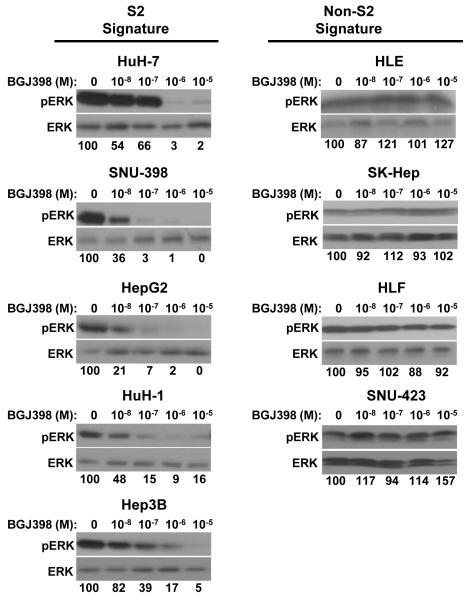

To further investigate downstream signaling pathways, western blot analysis was used to analyze MAPK signaling under exponentially increasing doses of BGJ398. In all five S2 cell lines, MAPK signaling was strongly attenuated at doses of BGJ398 above 1 μM as represented by decreased phosphorylation of ERK (Fig. 3). In contrast, the four less sensitive non-S2 cell lines showed no change in ERK phosphorylation in response to BGJ398. This suggested that while FGFR inhibition likely stalls proliferation of the S2 HCC subclass through downstream effects on the MAPK pathway. Non-S2 cell lines likely sustain MAPK signaling through receptors outside of the FGFR family.

Figure 3. FGFR inhibition decreases MAPK signaling in S2 HCC cell lines.

Inhibition of MAPK signaling under exponentially increasing doses of BGJ398 in S2 (HuH-7, SNU-398, HepG2, HuH-1, Hep3B) and non-S2 (HLE, SK-Hep, HLF, SNU-423) cell lines was assessed by western blot analysis of p-ERK. Total ERK was analyzed as a loading control. The ratio of pERK to total ERK was calculated for each drug concentration and the relative expression of this ratio was reported as percent of untreated control.

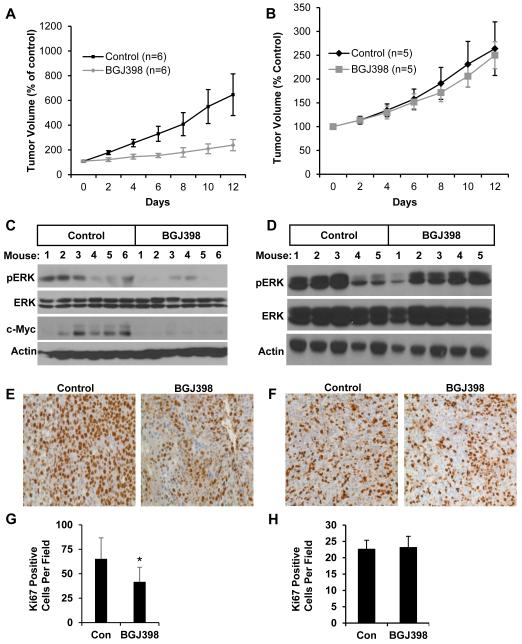

We further compared the response to FGFR inhibition between S1 and S2 cell lines in vivo. BGJ398 has previously been shown to be orally bioavailable and active against an FGFR3 overexpressing bladder cancer cell line,20 while information on bioavailability of AZD4547 following oral administration was not available. We established mouse xenografts with one S2 cell line (HuH-7) and one non-S2 cell line (SK-Hep). After tumors reached approximately 100 mm3 in size, we randomized animals to daily treatment with either BGJ398 (30mg/kg oral gavage) or control. FGFR inhibition had a robust and statistically significant (p=0.029) effect on delaying growth in xenograft tumors from the S2 HuH-7 cell line. On average, BGJ398-treated HuH-7 tumors were about one third the volume of control treated tumors (239 mm3 v 646 mm3) after 12 days of treatment (Fig. 4A). By comparison, BGJ398 did not delay growth of SK-Hep xenograft tumors (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. FGFR inhibition decreases S2 HCC xenograft tumor growth.

Growth curves and downstream effects of FGFR inhibition in xenograft tumors derived from the HuH-7 (S2) and SK-Hep (non-S2) cell lines. Xenograft tumor volume was measured over 14 days of treatment with either BGJ398 or vehicle control in (A) HuH-7 and (B) SK-Hep. Protein expression of p-ERK, total ERK, c-myc and β-actin in (C) HuH-7 and (D) SK-Hep xenograft tumors was assessed by western blot analysis after treatment with BGJ398 or vehicle control for 14 days. Ki67 staining in representative (E) HuH-7 and (F) SK-Hep xenograft tumors is shown. Proliferation, as assessed by Ki67 positive cells, was indexed in (G) HuH-7 and (H) SK-Hep derived xenografts after treatment with BGJ398 or vehicle control for 14 days.

Since BJG398 treatment inhibited MAPK signaling in all sensitive cells in vitro, we again characterized levels of pERK in xenografts. FGFR inhibition attenuated MAPK signaling in the S2 tumors, but not in non-S2 tumors. For HuH-7 tumors, intense levels of pERK were detected in 4 of 6 tumors in control treated mice, and moderate to undetectable levels of pERK were detected in BGJ398 treated mice (Fig. 4C). In SK-Hep tumors, MAPK signaling was not affected by BGJ398 treatment (Fig. 4D). MAPK inhibition has previously been shown to suppress c-myc in preclinical models of HCC.31 Since c-myc expression is a characteristic of the S2 gene signature,8 we also measured c-myc expression in the HuH-7 xenografts and observed that BGJ398 markedly downregulated its expression (Fig. 4C). Finally, we further confirmed that FGFR inhibition had an anti-proliferative effect through Ki67 staining (Fig. 4E,F). In the S2 signature HuH-7 derived xenografts, BGJ398 had a marked effect, decreasing Ki67 positive cells by 36% (p = 0.009) (Fig. 4G). In comparison, BGJ398 did not decrease the number of Ki67 positive cells in the non-S2 signature SK-Hep derived xenografts (Fig. 4H).

Response of human hepatoma cell lines to genetic FGFR knockdown

Since some S2 cell lines (SNU-398 and HuH-1) and the non-S2 cell lines expressed high levels of FGFR1, we tested their sensitivity to PD173074, an FGFR1-3 inhibitor. Both the S1 and S2 cell lines were resistant to PD173074 with the S2 cell line HuH-1 being the most sensitive with an IC50 of 4.11 μM (Supplementary Table 1). Likewise, PD173074 had marginal effects on ERK phosphorylation in the S2 cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 6). Taken together, these data suggested that the response to the pan-FGFR inhibitors BGJ398 and AZD4547 were most likely mediated by FGFR4.

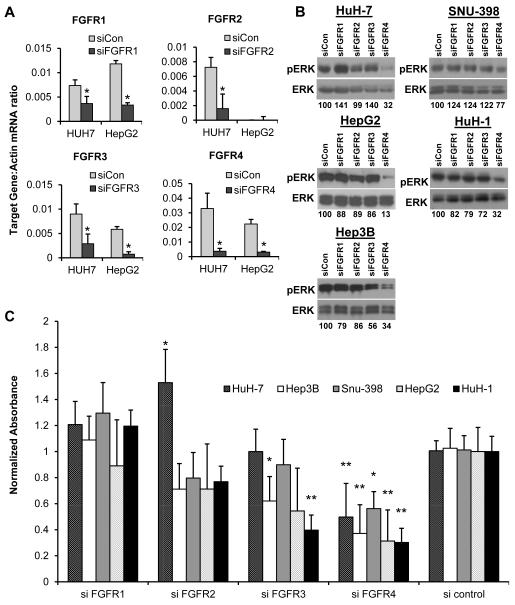

To determine if this gene signature-associated sensitivity was linked to expression of FGFR4 we performed siRNA transfection for each individual FGFR on all five sensitive S2 cell lines. Gene knockdown was confirmed to be at least 50% by qPCR on post-transfection day 3 (Fig. 5A and Supplementary Fig. 7). Our previous experiments had shown that pharmacologic FGFR inhibition attenuated MAPK signaling in S2 cell lines but not in non-S2 cell lines. MAPK signaling attenuation was also seen with knockdown of FGFR4 in all five S2 cell lines, but not with knockdown of FGFR1-3 (Fig. 5B). We further confirmed these findings, showing that a second siRNA construct targeting FGFR4 inhibited cell growth and attenuated MAPK signaling in all five S2 cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 8). Cell growth was evaluated by MTT assay following siRNA knockdown of each individual FGFR (Fig. 5C). FGFR4 knockdown slowed cell growth significantly in all five S2 cell lines from 30-56% of cell proliferation seen after control siRNA transfection. By comparison, only two cell lines (Hep3B and HuH-1) demonstrated slowed proliferation after FGFR3 knockdown, and HuH-7 was moderately stimulated by FGFR2 knockdown in comparison to the scrambled siRNA control. Taken as a whole, our experiments demonstrated that expression of FGFR3 and FGFR4 is limited to the S2 subclass of HCC, and that this subclass demonstrates greater sensitivity to pan-FGFR inhibition in vitro and in vivo. Mechanistic investigations suggested that FGFR4-MAPK signaling is predominantly responsible for this sensitivity.

Figure 5. FGFR4 knockdown suppresses S2 HCC cell proliferation.

Effects of genetic inhibition of FGFR1-4 in S2 (HuH-7, SNU-398, HepG2, HuH-1, Hep3B) cell lines. (A) Expression of FGFR1-4 was assessed by qPCR after transfection with targeted siRNA or a scrambled control and normalized to the expression of β-actin. Gene knockdown was confirmed to be at least 50% on post-transfection day 3 (HuH-7 and HepG2 shown; see also Supp Fig 3). (B) Effects on MAPK signaling after siRNA transfection was assessed by western blot analysis of p-ERK. Total ERK was analyzed as a loading control. The ratio of pERK to total ERK was calculated for each individual siRNA and the relative expression of this ratio was reported as percent of the scrambled control. (C) Cell proliferation, as assessed by MTT analysis, was measured after siRNA knockdown of each individual FGFR. A scrambled siRNA was used as a control.

Discussion

Gene-expression based subclasses of HCC that share genetic and clinical features have been reproducibly observed in numerous studies despite differences in geography and disease etiology.32 The S1, S2 and S3 gene signatures were derived using multiple unsupervised methods of analysis of multiple gene-expression databases, and share features of previously derived gene signatures.8 The S3 signature is most common amongst HCCs, representing approximately half of all clinical samples analyzed. It is generally less aggressive and is associated with better survival. The S3 signature has never been documented in an existing HCC cell line suggesting that cells of this HCC subtype might not be able to survive in vitro. This signature is associated with overexpression of glutamate-ammonia ligase (GLUL), leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein coupled receptor 5 (LGR5) and leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin-2 (LECT2)32 as well as somatic mutations in beta-catenin, commonly found in western HCC patients.33

In contrast to the S3 subclass of HCC, the S1 and S2 subclasses are associated with worse clinical prognosis, and share some genetic features including activation of E2F1 transcription factor and inactivation of p53.33 In clinically derived HCC datasets, the S1 signature represents 28-31% of tumors and the S2 signature represents 23-24% of tumors.8 The S1 subclass is associated with a locally invasive phenotype.8 The S1 gene signature overlaps with previously described signatures, including a transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) signature34 and a gene-signature for predicting early HCC recurrence.35 Characteristics of the S2 subclass include activation of myc and AKT, overexpression of AFP and IGF2 and downregulation of interferon-related genes.8 The S2 signature overlaps with a previously described subclassification system based on AFP expression36 as well as clinically derived gene signatures.37-38

We used a panel of 9 human HCC cell lines to explore the effects of FGFR inhibition on the S2 molecular subclass of HCC. In our study, the S2 gene signature was associated with greater sensitivity to two pan-FGFR inhibitors BGJ398 and AZD-4547. Cell proliferation was inhibited at least two-fold more in S2 than in non-S2 cell lines at all doses tested above 1 μM of BGJ398 and AZD4547. Differences between IC50s for the S2 and non-S2 group were also significant. In all five S2 cell lines, MAPK signaling was attenuated above doses of 1 μM BGJ398, while MAPK signaling in non-S2 cell lines was unchanged. This result was confirmed in vivo whereby xenografts derived from the S2 cell line HuH-7 were limited to one-third the volume of control tumors after two weeks of treatment with BGJ398 (p=0.029) and showed decreased phosphorylation of ERK. This stood in contrast to xenografts derived from the non-S2 cell line SK-Hep which had no change in growth and showed no difference in MAPK signaling in response to BGJ398.

We also explored the hypothesis that this sensitivity was linked to inhibition of one specific FGFR. All cell lines expressed FGFR1 and FGFR2, but FGFR3 and FGFR4 expression was limited to the S2 subclass. We performed siRNA knockdown of individual FGFRs on all five S2 cell lines. FGFR4 knockdown led to significant and robust inhibition of proliferation in all five S2 cell lines. In contrast, knockdown of FGFR1 and FGFR2 failed to inhibit proliferation, and FGFR3 knockdown had only a modest effect. In addition, S2 cell lines were not responsive to the FGFR1-3 inhibitor PD173074, as assessed by effects on both cell proliferation and MAPK signaling. Taken as a whole, this data suggests that the sensitivity of the S2 subclass of HCC to FGFR inhibition is predominantly mediated through FGFR4-MAPK signaling.

FGF19/FGFR4 signaling has been previously investigated in normal liver physiology and carcinogenesis. FGFR4 is expressed by mature hepatocytes and regulates bile acid synthesis.23-24 FGF19 is produced in the terminal ileum and acts as an endocrine ligand for FGFR4.25, 39-40 Supra-physiologic doses of FGF19 induce pericentral hepatocyte proliferation through activation of the MAPK pathway.41 Beyond this physiologic role, FGF19-FGFR4 signaling has a suggested role in the biology of HCC. Transgenic mice that over-express FGF19 develop HCC like lesions that produce AFP.26-27 When these transgenic mice are cross-bred with FGFR4 knockout mice, their progeny fail to develop liver tumors.28 Sawey et al. found that the introduction of a FGF19 coding amplicon into embryonic hepatoblasts lacking p53 and over-expressing c-myc transformed them into tumorigenic cells.29 Cross-analysis of genome-wide gene expression and genomic alteration data with cell line sensitivity data have also suggested that copy number gain of FGF19 as a result of 11q13.3 amplification was associated with sensitivity to FGFR inhibition in HCC cell lines.30 Thus, previous work on sensitivity to FGFR inhibition has predominantly focused on FGF19 and the 11q13.3 amplicon as potential biomarkers of pharmacologic sensitivity. Consistent with this, the HuH-7 cell line which contains a copy number gain of FGF19 and expresses all other aspects (FGFR4 and KLB) of a functioning FGF19/FGFR4 signaling pathway to high levels was the most sensitive cell line to both BGJ398 and AZD4547. Interestingly, our data suggest that the S2 signature can identify other cell lines that respond to FGFR inhibition.

The importance of this newly described association between a molecular subclass of HCC and FGFR inhibition is fourfold. First, several cell lines that do not contain the previously described amplification of chromosomal region 11q13.3 were found to be sensitive to FGFR4 inhibition, suggesting that a broader group of HCC may be susceptible to this strategy than previously described. Second, as FGF19 mRNA and FGFR4 were expressed universally and exclusively in the FGFR inhibition sensitive S2 cell lines, FGFR4 and FGF19 expression likely represent important single gene based biomarkers of this broader group of targetable HCC. It is possible that expression of FGFR4 in HCC tumors is important regardless of tumor FGF19 expression, as FGF19 is readily detectable in post prandial serum samples from healthy adults.42 Third, this sensitivity in an entire molecular subclass of HCC implies that multigene signatures can serve as biomarkers of FGFR4 inhibition sensitivity. Lastly, our data suggests that drugs designed to specifically target FGFR4 may be equally effective against HCC but possibly with less toxicity than pan-FGFR inhibitors.

Multi-gene signatures may be superior predictors of outcome in comparison to single-gene based biomarkers as they can reflect signaling events that occur after the transcription or translation of the target of interest.7 For example, expression of downstream targets of estrogen receptor signaling are more predictive of clinical outcomes in breast cancer than expression levels of estrogen receptor alone.43 Similarly, the biomarker for sensitivity of colorectal cancer to EGFR inhibition44 could be described as a multigene signature as it relies on the analysis of two gene products, expression of both EGFR and wild-type KRAS.

Unsupervised multi-gene based classification of tumors are able to reproduce previously known classifications of cancer that are predictive of therapeutic response and has been proposed as an unbiased method for discovering therapeutic cancer classes for over a decade.45 The S1, S2, and S3 molecular subclassification of HCC used here has recently been implemented in an FDA-approved diagnostic platform46 (Elements assay, Nanostring) and may become an important tool to organize clinical trials in HCC and may play a role in the personalization of HCC treatment with target therapies.47 Although it should be mentioned that percutaneous biopsy of HCC carries a potential risk, albeit low, of tumor seeding along the needle track.48

The S2 subclass has previously demonstrated sensitivity to a number of targeted therapies currently under investigation. Using an E-cadherin expressing panel of cell lines similar to the current panel of S2 cell lines, we have previously demonstrated that E-cadherin expression correlated with sensitivity to EGFR inhibition with erlotinib, gefitinib and cetuximab.10 The S2 subclass of HCC has also shown an association with IGF-2 expression and IGF-1R activation.12 Zhao et al, used a similar panel of HCC cell lines to describe the correlation between E-cadherin expression and sensitivity to dual inhibition of the insulin receptor (IR) and IGF-1R with OSI-906.11 They additionally described how the EGFR pathway could compensate for IR/IGF-1R inhibition, and demonstrated that erlotinib and OSI-906 showed synergistic activity in vitro. This suggests that classifying drug sensitivity by molecular subtypes of cancer may help guide rational combinations of targets. Combining IR/IGF1R inhibition with FGFR inhibition is an intriguing combination as there is emerging evidence that there is cross talk between insulin signaling and FGFR4 in normal physiology. Overfed mice with FGFR4 deficient livers demonstrate greater hyperglycemia and insulin resistance than wildtype controls.49 In addition, Scheller et al. have also shown that a small panel of S2 cell lines are responsive to BGJ398 and that this effect could be enhanced with the addition of an mTOR inhibitor.50 Finally, while non-S2 phenotypes were associated with resistance to therapy in most preclinical investigations above, a non-AFP secreting “progenitor-like” molecular subtype of HCC, was recently reported to be sensitive to the Src/Abl inhibitor dasatinib.13, 51

There is significant evidence that FGFR4 over expression is common enough in human HCC to make this strategy worthy of clinical trials for HCC. The S2 gene signature represents over a quarter of all patients in clinical datasets curated from both eastern and western hemispheres.8 Ho et al. quantified FGFR4 mRNA in 57 HCC patients and found at least two-fold overexpression in one third of tumors compared to matched normal tissue.52 Immunostaining experiments have also estimated FGFR4 to be upregulated in one-third of HCC patients.28 The recent lack of survival benefit demonstrated for brivanib in second line treatment of HCC53 is irrelevant to investigations of FGF19-FGFR4 signaling as brivanib predominantly targets FGFR1 in addition to VEGFR.54 Another important point regarding specificity of receptor inhibition is that while BGJ398 and AZD-4547 target all four FGFRs, they inhibit FGFR1-3 approximately tenfold more potently than FGFR4.20-21 Agents targeting FGFR4 with greater specificity and potency are under development and may be explored in HCC clinical trials in the near future.55

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the S2 gene signature is associated with greater sensitivity to two pan-FGFR inhibitors, and that this sensitivity is likely predominantly mediated through FGFR4-MAPK signaling. This builds on previous descriptions of FGFR4 sensitivity in that several cell lines that do not contain the previously described amplification of chromosomal region 11q13.3 were found to be sensitive to FGFR4 inhibition, suggesting that a broader group of HCC may be susceptible to this strategy than previously described. FGFR4 expression and S2 gene signature enrichment are both found in about a third of HCC patients making this a robust area for exploration with clinical trials. More specific inhibitors of FGFR4 are under development and may be explored in HCC clinical trials in the near future. The S2 gene signature may be an important biomarker for response to this therapy.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Impact of the Work: This study demonstrates that a previously identified gene expression signature representing a subclass of human HCCs predicts response to pan-FGFR inhibitors. Importantly, the anti-proliferative effects are mediated through FGFR4 and occur in HCC cell lines that do not harbor FGF19 amplification and therefore our results suggest that a larger number of tumors could be susceptible to specific FGFR4 inhibitors that are currently under development.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers T32 CA071345 to B.S., D.K.D. and K.K.T., R01 DK099558 to Y.H. and K01 CA140861 to B.C.F.) and the Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Surgery (K.K.T.).

Abbreviations

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- AFP

alpha fetoprotein

- IGF-2

insulin-like growth factor 2

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- IR

insulin receptor

- IGF-1R

insulin-like growth factor receptor 1

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- FGFR

FGF receptor

- MAPK

mitogen activated protein kinase

- VEGFR2

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2

- KLB

beta-klotho

- BCA

bicinchoninic acid

- TBS/T

TBS/0.1% Tween 20

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- ERK

extracellular signal–regulated kinase

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay

- siRNA

short interfering ribonucleic acid

- H-E

hematoxylin-eosin

- qPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- GLUL

glutamate-ammonia ligase

- LGR5

leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein coupled receptor 5

- LECT2

leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin-2

- TGF-beta

transforming growth factor beta

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;2:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altekruse SF, McGlynn KA, Reichman ME. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence, mortality, and survival trends in the United States from 1975 to 2005. J Clin Oncol. 2009;9:1485–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;4:378–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardoso F, Van't Veer L, Rutgers E, Loi S, Mook S, Piccart-Gebhart MJ. Clinical application of the 70-gene profile: the MINDACT trial. J Clin Oncol. 2008;5:729–35. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.3222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sparano JA, Paik S. Development of the 21-gene assay and its application in clinical practice and clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;5:721–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan IB, Tan P. Genetics: an 18-gene signature (ColoPrint(R)) for colon cancer prognosis. Nat Rev Clin Onco. 2011;3:131–3. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van't Veer LJ, Bernards R. Enabling personalized cancer medicine through analysis of gene-expression patterns. Nature. 2008;7187:564–70. doi: 10.1038/nature06915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoshida Y, Nijman SM, Kobayashi M, Chan JA, Brunet JP, Chiang DY, et al. Integrative transcriptome analysis reveals common molecular subclasses of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2009;18:7385–92. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JS, Thorgeirsson SS. Functional and genomic implications of global gene expression profiles in cell lines from human hepatocellular cancer. Hepatology. 2002;5:1134–43. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuchs BC, Fujii T, Dorfman JD, Goodwin JM, Zhu AX, Lanuti M, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and integrin-linked kinase mediate sensitivity to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition in human hepatoma cells. Cancer Res. 2008;7:2391–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao H, Desai V, Wang J, Epstein DM, Miglarese M, Buck E. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition predicts sensitivity to the dual IGF-1R/IR inhibitor OSI-906 in hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;2:503–13. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tovar V, Alsinet C, Villanueva A, Hoshida Y, Chiang DY, Sole M, et al. IGF activation in a molecular subclass of hepatocellular carcinoma and pre-clinical efficacy of IGF-1R blockage. J Hepatol. 2010;4:550–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finn RS, Aleshin A, Dering J, Yang P, Ginther C, Desai A, et al. Molecular subtype and response to dasatinib, an Src/Abl small molecule kinase inhibitor, in hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines in vitro. Hepatology. 2013;5:1838–46. doi: 10.1002/hep.26223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dieci MV, Arnedos M, Andre F, Soria JC. Fibroblast growth factor receptor inhibitors as a cancer treatment: from a biologic rationale to medical perspectives. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:264–79. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turner N, Grose R. Fibroblast growth factor signalling: from development to cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;2:116–29. doi: 10.1038/nrc2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SH, Lopes de Menezes D, Vora J, Harris A, Ye H, Nordahl L, et al. In vivo target modulation and biological activity of CHIR-258, a multitargeted growth factor receptor kinase inhibitor, in colon cancer models. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;10:3633–41. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hilberg F, Roth GJ, Krssak M, Kautschitsch S, Sommergruber W, Tontsch-Grunt U, et al. BIBF 1120: triple angiokinase inhibitor with sustained receptor blockade and good antitumor efficacy. Cancer Res. 2008;12:4774–82. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhide RS, Cai ZW, Zhang YZ, Qian L, Wei D, Barbosa S, et al. Discovery and preclinical studies of (R)-1-(4-(4-fluoro-2-methyl-1H-indol-5-yloxy)-5-methylpyrrolo[2,1-f][1,2,4]triazin-6-yloxy)propan- 2-ol (BMS-540215), an in vivo active potent VEGFR-2 inhibitor. J Med Chem. 2006;7:2143–6. doi: 10.1021/jm051106d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laird AD, Vajkoczy P, Shawver LK, Thurnher A, Liang C, Mohammadi M, et al. SU6668 is a potent antiangiogenic and antitumor agent that induces regression of established tumors. Cancer Res. 2000;15:4152–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gavine PR, Mooney L, Kilgour E, Thomas AP, Al-Kadhimi K, Beck S, et al. AZD4547: an orally bioavailable, potent, and selective inhibitor of the fibroblast growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase family. Cancer Res. 2012;8:2045–56. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guagnano V, Furet P, Spanka C, Bordas V, Le Douget M, Stamm C, et al. Discovery of 3-(2,6-dichloro-3,5-dimethoxy-phenyl)-1-{6-[4-(4-ethyl-piperazin-1-yl)-phenylamin o]-pyrimidin-4-yl}-1-methyl-urea (NVP-BGJ398), a potent and selective inhibitor of the fibroblast growth factor receptor family of receptor tyrosine kinase. J Med Chem. 2011;20:7066–83. doi: 10.1021/jm2006222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolf J, Camidge RD, Perez JM, et al. A phase I dose escalation study of NVP-BGJ398, a selective pan FGFR inhibitor in genetically preselected advanced solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2012;8 Abstract LB-122. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes SE. Differential expression of the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) multigene family in normal human adult tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 1997;7:1005–19. doi: 10.1177/002215549704500710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones SA. Physiology of FGF15/19. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;728:171–82. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0887-1_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holt JA, Luo G, Billin AN, Bisi J, McNeill YY, Kozarsky KF, et al. Definition of a novel growth factor-dependent signal cascade for the suppression of bile acid biosynthesis. Genes Dev. 2003;13:1581–91. doi: 10.1101/gad.1083503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicholes K, Guillet S, Tomlinson E, Hillan K, Wright B, Frantz GD, et al. A mouse model of hepatocellular carcinoma: ectopic expression of fibroblast growth factor 19 in skeletal muscle of transgenic mice. Am J Pathol. 2002;6:2295–307. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61177-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Desnoyers LR, Pai R, Ferrando RE, Hotzel K, Le T, Ross J, et al. Targeting FGF19 inhibits tumor growth in colon cancer xenograft and FGF19 transgenic hepatocellular carcinoma models. Oncogene. 2008;1:85–97. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.French DM, Lin BC, Wang M, Adams C, Shek T, Hotzel K, et al. Targeting FGFR4 inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma in preclinical mouse models. PLoS One. 2012;5:e36713. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sawey ET, Chanrion M, Cai C, Wu G, Zhang J, Zender L, et al. Identification of a therapeutic strategy targeting amplified FGF19 in liver cancer by Oncogenomic screening. Cancer Cell. 2011;3:347–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guagnano V, Kauffmann A, Wohrle S, Stamm C, Ito M, Barys L, et al. FGFR genetic alterations predict for sensitivity to NVP-BGJ398, a selective pan-FGFR inhibitor. Cancer Discov. 2012;12:1118–33. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huynh H, Chow PK, Soo KC. AZD6244 and doxorubicin induce growth suppression and apoptosis in mouse models of hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;9:2468–76. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zucman-Rossi J, Benhamouche S, Godard C, Boyault S, Grimber G, Balabaud C, et al. Differential effects of inactivated Axin1 and activated beta-catenin mutations in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Oncogene. 2007;5:774–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoshida Y, Toffanin S, Lachenmayer A, Villanueva A, Minguez B, Llovet JM. Molecular classification and novel targets in hepatocellular carcinoma: recent advancements. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;1:35–51. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coulouarn C, Factor VM, Thorgeirsson SS. Transforming growth factor-beta gene expression signature in mouse hepatocytes predicts clinical outcome in human cancer. Hepatology. 2008;6:2059–67. doi: 10.1002/hep.22283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woo HG, Park ES, Cheon JH, Kim JH, Lee JS, Park BJ, et al. Gene expression-based recurrence prediction of hepatitis B virus-related human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Can Res. 2008;7:2056–64. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamashita T, Forgues M, Wang W, Kim JW, Ye Q, Jia H, et al. EpCAM and alpha-fetoprotein expression defines novel prognostic subtypes of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2008;5:1451–61. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang SM, Ooi LL, Hui KM. Identification and validation of a novel gene signature associated with the recurrence of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Can Res. 2007;21:6275–83. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurokawa Y, Matoba R, Takemasa I, Nagano H, Dono K, Nakamori S, et al. Molecular-based prediction of early recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2004;2:284–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie MH, Holcomb I, Deuel B, Dowd P, Huang A, Vagts A, et al. FGF-19, a novel fibroblast growth factor with unique specificity for FGFR4. Cytokine. 1999;10:729–35. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goetz R, Beenken A, Ibrahimi OA, Kalinina J, Olsen SK, Eliseenkova AV, et al. Molecular insights into the klotho-dependent, endocrine mode of action of fibroblast growth factor 19 subfamily members. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;9:3417–28. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02249-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu X, Ge H, Lemon B, Vonderfecht S, Weiszmann J, Hecht R, et al. FGF19-induced hepatocyte proliferation is mediated through FGFR4 activation. J Biol Chem. 2010;8:5165–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.068783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lundasen T, Galman C, Angelin B, Rudling M. Circulating intestinal fibroblast growth factor 19 has a pronounced diurnal variation and modulates hepatic bile acid synthesis in man. J Intern Med. 2006;6:530–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van 't Veer LJ, Dai H, van de Vijver MJ, He YD, Hart AA, Mao M, et al. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature. 2002;6871:530–6. doi: 10.1038/415530a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Makhson A, Hartmann JT, Aparicio J, de Braud F, et al. Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin with and without cetuximab in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;5:663–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Golub TR, Slonim DK, Tamayo P, Huard C, Gaasenbeek M, Mesirov JP, et al. Molecular classification of cancer: class discovery and class prediction by gene expression monitoring. Science. 1999;5439:531–7. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tan PS, Nakagawa S, Goossens N, Venkatesh A, Huang T, Ward SC, et al. Clinicopathological indices to predict hepatocellular carcinoma molecular classification. Liver Int. 2015 doi: 10.1111/liv.12889. [epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Llovet JM, Hernandez-Gea V. Hepatocellular carcinoma: reasons for phase III failure and novel perspectives on trial design. Clin Can Res. 2014;8:2072–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jain D. Tissue diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2014;S3:S67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2014.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang X, Yang C, Luo Y, Jin C, Wang F, McKeehan WL. FGFR4 prevents hyperlipidemia and insulin resistance but underlies high-fat diet induced fatty liver. Diabetes. 2007;10:2501–10. doi: 10.2337/db07-0648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scheller T, Hellerbrand C, Moser C, Schmidt K, Kroemer A, Brunner SM, et al. mTOR inhibition improves fibroblast growth factor receptor targeting in hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(5):841–50. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deshmukh M, Hoshida Y. Genomic profiling of cell lines for personalized targeted therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2013;6:2207. doi: 10.1002/hep.26407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ho HK, Pok S, Streit S, Ruhe JE, Hart S, Lim KS, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 regulates proliferation, anti-apoptosis and alpha-fetoprotein secretion during hepatocellular carcinoma progression and represents a potential target for therapeutic intervention. J Hepatol. 2009;1:118–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Llovet JM, Decaens T, Raoul JL, Boucher E, Kudo M, Chang C, et al. Brivanib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma who were intolerant to sorafenib or for whom sorafenib failed: results from the randomized phase III BRISK-PS study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;28:3509–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.3009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cai ZW, Zhang Y, Borzilleri RM, Qian L, Barbosa S, Wei D, et al. Discovery of brivanib alaninate ((S)-((R)-1-(4-(4-fluoro-2-methyl-1H-indol-5-yloxy)-5-methylpyrrolo[2,1-f][1,2,4] triazin-6-yloxy)propan-2-yl)2-aminopropanoate), a novel prodrug of dual vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 and fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 kinase inhibitor (BMS-540215) J Med Chem. 2008;6:1976–80. doi: 10.1021/jm7013309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Norman RA, Schott AK, Andrews DM, Breed J, Foote KM, Garner AP, et al. Protein-ligand crystal structures can guide the design of selective inhibitors of the FGFR tyrosine kinase. J Med Chem. 2012;11:5003–12. doi: 10.1021/jm3004043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.