Abstract

Mutations in the MAPT gene coding for the tau protein are one of the most common causes of familial frontotemporal dementia (FTD). In a previously described family with the V337M mutation in MAPT, we now report an affected woman who died at age 92 with a >40 year duration of symptoms, more than three times the mean disease duration in her family (13.8 years). Neuropathology showed the typical findings of a diffuse tauopathy. Conversely, her 67-year-olds on with the same mutation remains asymptomatic more than 15 years beyond the mean age of onset in the family (51.5 years). These two cases demonstrate the marked variability in onset and duration of familial FTD and underscore the difficulties of discussing these issues with patients and families. The presumed genetic and environmental factors influencing these parameters remain largely unknown.

Keywords: dementia, frontotemporal dementia, MAPT, tau, penetrance

INTRODUCTION

Mutations in three genes, namely MAPT, GRN, and C9orf72, cause frontotemporal dementia (FTD) in the majority of affected families. Mutations in MAPT were the first to be recognized [Hutton et al., 1998; Poorkaj et al., 1998; Spillantini et al., 1998]. Seattle family A with the V337M mutation was one of the first such families to be reported and has been described at the phenotypic, genetic linkage, and mutation identification levels [Sumi et al., 1992; Bird et al., 1997; Poorkaj et al., 1998].

FTD typically has an onset in the 6th decade and disease duration from onset to death of approximately 10 years [Hodges et al., 2003]. Considerable variability in onset and duration is well recognized, but the factors influencing these variables are poorly understood.

The Seattle A family has been followed for more than 35 years. Here, we report two unusual outliers in this family: A woman with an extraordinarily long duration of disease and her mutation carrier son with surprisingly delayed penetrance of symptoms.

The Family

The family originated in what is now the Czech Republic. There have been 18 affected persons over four generations (see pedigree in Poorkaj et al., 1998). Mean age of onset is 51.5 ± 7.4 years, mean disease duration is 13.8 ± 7.8 years, and mean age at death is 66.9 ± 7.0 years [Bird et al., 1997]. Affected family members typically develop psychiatric symptoms in the 5th or 6th decade that slowly progress to a severe dementia. The early symptoms have included social withdrawal and reclusiveness, suspiciousness and paranoid ideas, auditory hallucinations, and bizarre compulsive activities sometimes associated with aggressive behavior. Late in the disease, there are frequently hyper oral behaviors, increased muscle tone, mutism, and myoclonic jerks. Five autopsies in this family have all shown a diffuse tauopathy with neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) in neocortex, amygdala, and parahippocampal gyrus. The hippocampus is relatively spared but shows neuronal loss with gliosis. Some cases have shown marked atrophy of the amygdala. There have been no diffuse or neuritic amyloid plaques, Lewy bodies, Pick bodies, or ballooned achromatic neurons.

Family Member III-5

This woman had a high school education, was a successful homemaker, and had no history of drug or alcohol abuse. At approximately age 47, she was noted to have a mild but distinct personality change. She had inappropriate comments during conversations and expressed tangential, irrelevant thoughts and ideas that irritated and frustrated her family and friends. This personality quirk continued without marked progression until she was 55 years old, when her mental status began deteriorating coincident with the accidental death of her husband. She became distant, uncommunicative, and temperamental. She became increasingly confused and lost the ability to perform common tasks such as driving and cooking. By her late 50s, she could no longer live independently and moved in with her adult children for the remainder of her life. Examination at age 61 showed no medical or neurological deficits but her recent memory, calculations, and problem solving were impaired. Speech was characterized by mainly yes or no answers. Her affect was labile, quickly changing from laughing to belligerent and uncooperative. She frequently wandered away from home requiring her family to build a fence to contain her. She was disinhibited and would lash out verbally against “fat people.” She had no hallucinations. Examination at age 72 showed normal gait and reflexes. She was oriented to only person, could write her name legibly but could not complete the Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE). She showed repetitive behavior such as sucking and biting her index finger. She stopped talking at age 75 but continued to follow simple commands. She stopped walking at about age 80. She continued to take soft food by mouth until her death; her family provided large amounts of pureed fruits and vegetables. She died of aspiration pneumonia at age 92 with an approximately 45 year duration of symptomatic disease. Her APOE genotype was 2/3.

Neuropathology

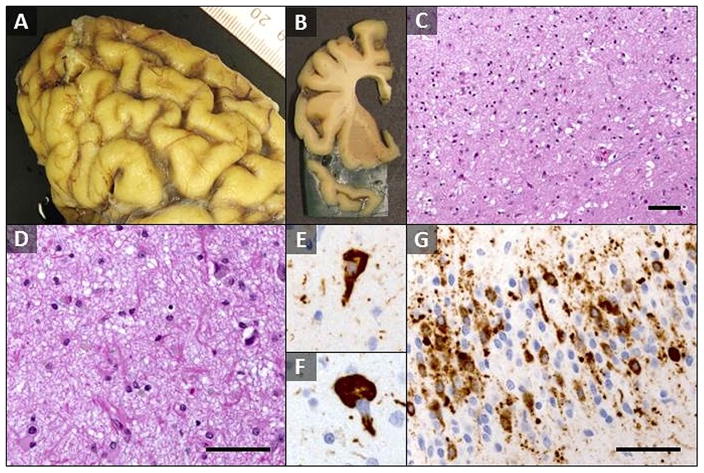

Total brain weight was 835 grams and there was severe fronto-temporal and moderate parietal cortical atrophy (Fig. 1A and B). There was diffuse neuronal loss and astrogliosis throughout the cerebral cortex (Fig. 1C) and hippocampus, subcortical white matter degeneration and extensive tau deposition. Temporal cortex was severely affected; frontal cortex was moderately to severely affected. Parietal and occipital cortex was mildly affected. Spongiotic change was most prominent superficially in frontal and temporal cortex. The hippocampus was involved with near complete loss of CA1 and subiculum pyramidal neurons continuing into entorhinal and medial temporal cortex with associated marked astrogliosis (Fig. 1D). Dentate granule neurons and CA 2–4 neurons were preserved relative to other areas of the hippocampus. There was mild to focally moderate neuronal loss and gliosis in the caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus, while substantia nigra and locus ceruleus exhibited severe neuronal loss and associated gliosis. Phospho-tau immunohistochemistry demonstrated extensive pathological tau deposition most severe in hippocampus and temporal cortex in the form of dense tau neurites, scattered neurofibrillary and globose tangles (Fig. 1E and F), and prominent astrocytic tau. Dentate gyrus exhibited prominent mix of neuronal and glial tau (Fig. 1G). Subcortical white matter was less involved, and primarily took the form of tau neurites and rare aggregates including candidate coiled bodies. Overall neuronal tau, particularly involving neuronal processes, was more prominent in most areas than diverse forms of glial tau. Braak staging was not performed because of the presence of a diffuse tauopathy. Amyloid (A) β burden was low and limited to cerebral cortex; neuritic plaque density was sparse by CERAD criteria, Thal phase amyloid plaque distribution was 1 of 5, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy was not appreciated. Lewy bodies were absent, except for two identified in amygdala and there were no Pick bodies. Although a 5 cm left middle cerebral artery territory remote infarct was present, cerebral microinfarcts were not identified.

FIG. 1.

Neuropathologic findings in long duration MAPT (V337M) patient. (A) Gross photograph of the left frontal cortex demonstrated severe cortical atrophy with widened cortical sulci separating thin superior and middle frontal gyri. (B) Coronal section of left frontal lobe with marked atrophy of superior and middle frontal gyri as well as temporal pole and associated lateral ventricle enlargement. (C) H&E/LFB stain of layers I–III of frontal cortex demonstrates marked neuron loss, diffuse gliosis, and associated spongiotic change (200X magnification). (D) H&E/LFB stain of hippocampus CA1 field demonstrated near complete loss of pyramidal neurons and associated marked astrogliosis (400× magnification). (E and F) Phospho-tau immunohistochemistry demonstrating flame-shaped neurofibrillary tangle (E) and globose tangle (F) in frontal cortex neurons (Tau2, 600× magnification). (G) Phospho-tau immunohistochemistry demonstrated extensive neuronal and glial tau in dentate gyrus granule neuron layers. Neurofibrillary tangles are rare, whereas pre-tangles and other neuronal tau deposition is present, in addition to abundant tau neurites and occasional glial inclusions (Tau2, 400× magnification). Scale bars = 100 μm.

Index Subject’s Son

This 67-year-old man is a self-employed carpenter and construction worker with a community college education. He has probable dyslexia as well as a past medical history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, and head trauma resulting from an accidental fall at age 54. At age 59, he developed several anxiety attacks associated with pain in various parts of his body, sensitivity to noise, and excessive worry. Neurological and mental status examination at that time was normal except for a mildly rambling conversation; he remained fully employed. His anxiety responded well to alprazolam and citalopram, which were discontinued within a year. MRI brain scan was normal. His neurological and mental status examination remained normal at age 64 and he scored 26 out of 30 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Test (MoCA). At age 67, he lives independently with his wife and continues to work full time. His neurological and mental status examinations remain stable. He has normal word fluency, conversation, and appropriate language, with MoCA score unchanged at 26. His Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) score was 0. No further detailed neuropsychologic tests have been performed. His medications include multiple B vitamins, Co-enzyme Q10 (100 mg), Vitamin E, Vitamin D3, crustacean oil, and losartan.

DISCUSSION

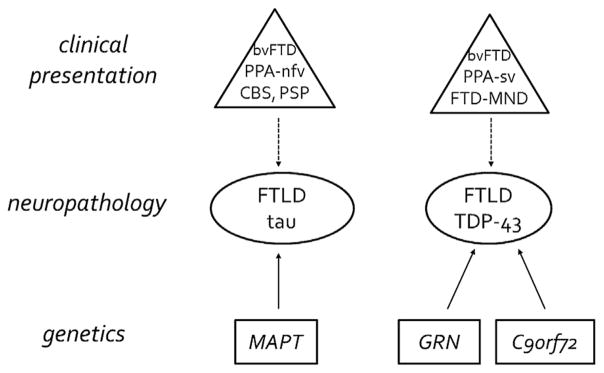

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) has been divided into several different sub-categories based on major clinical symptoms, neuropathology, and genetics [Wang et al., 2013; Lashley et al., 2015] (Fig. 2). The disease in the present family is classified as behavioral FTD based on clinical manifestations, a diffuse tauopathy based on neuropathology, and MAPT-associated FTD based on genetic mutation.

FIG. 2.

Summary of FTD phenotypes, neuropathology, and genetics found in the majority of cases. Neuropathologic findings in frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) are primary characterized as tau or TDP-43 intracellular inclusions, with FTLD-FUS comprising most of remaining 5–10%. Clinical presentation is much more varied (behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia [bvFTD]; primary progressive aphasia, nonfluent/agrammatic variant [PPA-nfv]; corticobasal syndrome [CBS]; progressive supranuclear palsy [PSP]; primary progressive aphasia, semantic variant [PPA-sv], frontotemporal dementia with motor neuron disease [FTD-MND]) and is not 100% predictive of underlying neuropathology (dashed line). FTD-MND is also noted to have ubiquitin and p62 positive but TDP-43 negative neuronal inclusions [Mackenzie et al., 2014]. Roughly 30% of individuals with FTD carry a mutation or expansion of one of three genes: MAPT, GRN, or C9orf72, with 90–100% penetrance; additional rarer genes are VCP, TBK1, and CHMP2B.

The age of onset of symptoms varies considerably in behavioral variant FTD, but is typically in the 50s. One study found a mean onset age of 56.5 years (±7.6) [Hodges et al., 2003] and another found onset at 57.5 years (±9.7) [Johnson et al., 2005]. Disease duration from onset to death varies greatly, but is typically less than ten years, being about eight years in the Hodges et al. [2003] study where the mean age at death was 64.7 years (±8.5). Roberson et al. [2005] reported similar data and noted that FTD progresses to death faster than typical Alzheimer disease (AD) with mean durations of 8.7 versus 11.8 years, respectively.

In the present family, the mean age at onset has been 51.5 ± 7.4 years. The mean disease duration in this family has been longer than that typically reported in the literature being 13.8 ± 7.8 years with mean death at 66.9 ± 7.0 years.

The two subjects described in this report are presented to highlight unusually long disease duration and delayed symptom penetrance in a MAPT mutation carrier. The mother in this family had symptom onset at approximately age 47. Although symptom onset can be difficult to determine, her family consistently identified this as the age at which she had a distinct change in personality. This age of onset is well within the range of other members of her family. Remarkably, she then lived for more than 40 years, dying at age 92. Neuro-pathologic features were consistent with the long disease duration, with brain weight limited to only 835 g and showing a severe, diffuse tauopathy. The reasons for her long disease duration are unknown. She was neither a smoker nor a drinker, did not develop cancer or cardiac disease and had an ApoE genotype of 2/3. She did have a stroke that may have contributed to her death. Her family attributed her long life to her diet heavily weighted toward fruits and vegetables, but this evidence is purely anecdotal. Her clinical manifestations were similar to other elderly subjects with FTD [Baborie et al., 2012].

The patient’s son carries the same V337M mutation as his mother, and is essentially asymptomatic, living independently, and gainfully employed at age 67. His brain MRI at age 64 showed no signs of atrophy. Like his mother, he is neither a smoker nor a drinker and he has not developed cancer, but does have coronary artery disease. His ApoE genotype is unknown. He has had treatment with B vitamins, fish oil, and Co-Enzyme Q10, but there is no way to determine how they may have affected his disease trajectory. We are using the term “delayed penetrance” to describe this man because (1) he carries the pathogenic MAPT mutation, (2) he shows no obvious signs of FTD at age 67 (15 years beyond the mean age of onset in this family) and (3) evidence that the vast majority of mutations in MAPT become “penetrant” (i.e., symptomatic) by some age.

These two cases within a single family emphasize our relative ignorance concerning factors influencing onset and disease duration in FTD as well as other neurodegenerative diseases. Apolipoprotein E is one such genetic factor influencing AD, but its role in FTD is unclear and controversial [Bernardi et al., 2006; Seripa et al., 2011; Hernández et al., 2014]. Lee et al. [2015] have reported three genes (SNX25, PDLIM3, SORBS2) modifying age of onset in a specific mutation (G206A) in PSEN1 in familial AD, but the effect of these genes in FTD is unknown. A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in TMEM106B has been shown to modify penetrance in GRN-related FTD [Finch et al., 2011] and motor neuron versus behavioral expression in C9orf72-related ALS/FTD [van Blitterswijk et al., 2014], but reported to have no effect in MAPT-related FTD [Finch et al., 2011]. There are likely to be a large number of both environmental and genetic factors impacting onset and duration of all types of FTD and these remain to be determined. The identification of such factors is highly important because they will provide clues to the treatment and prevention of FTD.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: NIH/NIA ADRC; Grant number: P50-AG005136; Grant sponsor: VA Research Funds.

We thank the members of this family for valuable assistance over many years.

References

- Baborie A, Griffiths TD, Jaros E, Momeni P, McKeith IG, Burn DJ, Keir G, Larner AJ, Mann DM, Perry R. Frontotemporal dementia in elderly individuals. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(8):1052–1060. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.3323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird TD, Wijsman EM, Nochlin D, Leehey M, Sumi SM, Payami H, Poorkaj P, Nemens E, Rafkind M, Schellenberg GD. Chromosome 17 and hereditary dementia: Linkage studies in three non-Alzheimer families and kindreds with late-onset FAD. Neurology. 1997;48(4):949–954. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.4.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi L, Maletta RG, Tomaino C, Smirne N, Di Natale M, Perri M, Longo T, Colao R, Curcio SA, Puccio G, Mirabelli M, Kawarai T, Rogaeva E, St George Hyslop PH, Passarino G, De Benedictis G, Bruni AC. The effects of APOE and tau gene variability on risk of frontotemporal dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27(5):702–709. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch N, Carrasquillo MM, Baker M, Rutherford NJ, Coppola G, Dejesus-Hernandez M, Crook R, Hunter T, Ghidoni R, Benussi L, Crook J, Finger E, Hantanpaa KJ, Karydas AM, Sengdy P, Gonzalez J, Seeley WW, Johnson N, Beach TG, Mesulam M, Forloni G, Kertesz A, Knopman DS, Uitti R, White CL, III, Caselli R, Lippa C, Bigio EH, Wszolek ZK, Binetti G, Mackenzie IR, Miller BL, Boeve BF, Younkin SG, Dickson DW, Petersen RC, Graff-Radford NR, Geschwind DH, Rademakers R. TMEM106B regulates progranulin levels and the penetrance of FTLD in GRN mutation carriers. Neurology. 2011;76(5):467–474. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820a0e3b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández I, Mauleón A, Rosense-Roca M, Alegret M, Vinyes G, Espinosa A, Sotolongo-Grau O, Becker JT, Valero S, Tarraga L, López OL, Ruiz A, Boada M. Identification of misdiagnosed fronto-temporal dementia using APOE genotype and phenotype-genotype correlation analyses. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2014;11(2):182–191. doi: 10.2174/1567205010666131212120443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges JR, Davies R, Xuereb J, Kril J, Halliday G. Survival in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2003;61(3):349–354. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000078928.20107.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton M, Lendon CL, Rizzu P, Baker M, Froelich S, Houlden H, Pickering-Brown S, Chakraverty S, Isaacs A, Grover A, Hackett J, Adamson J, Lincoln S, Dickson D, Davies P, Petersen RC, Stevens M, de Graaff E, Wauters E, van Baren J, Hillebrand M, Joosse M, Kwon JM, Nowotny P, Che LK, Norton J, Morris JC, Reed LA, Trojanowski J, Basun H, Lannfelt L, Neystat M, Fahn S, Dark F, Tannenberg T, Dodd PR, Hayward N, Kwok JB, Schofield PR, Andreadis A, Snowden J, Craufurd D, Neary D, Owen F, Oostra BA, Hardy J, Goate A, van Swieten J, Mann D, Lynch T, Heutink P. Association of missense and 5′-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature. 1998;393(6686):702–705. doi: 10.1038/31508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JK, Diehl J, Mendez MF, Neuhaus J, Shapira JS, Forman M, Chute DJ, Roberson ED, Pace-Savitsky C, Neumann M, Chow TW, Rosen HJ, Forstl H, Kurz A, Miller BL. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: Demographic characteristics of 353 patients. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(6):925–930. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.6.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashley T, Rohrer JD, Mead S, Revesz T. Review: An update on clinical, genetic and pathological aspects of frontotemporal lobar degenerations. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2015 doi: 10.1111/nan.12250. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Cheng R, Vardarajan B, Lantigua R, Reyes-Dumeyer D, Ortmann W, Graham RR, Bhangale T, Behrens TW, Medrano M, Jiménez-Velázquez IZ, Mayeux R. Genetic modifiers of age at onset in carriers of the G206A mutation in psen1 with familial alzheimer disease among caribbean hispanics. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(9):1043–1051. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie IR, Frick P, Neumann M. The neuropathology associated with repeat expansions in the C9ORF72 gene. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127(3):347–357. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1232-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poorkaj P, Bird TD, Wijsman E, Nemens E, Garruto RM, Anderson L, Andreadis A, Wiederholt WC, Raskind M, Schellenberg GD. Tau is a candidate gene for chromosome 17 frontotemporal dementia. Ann Neurol. 1998;43(6):815–825. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson ED, Hesse JH, Rose KD, Slama H, Johnson JK, Yaffe K, Forman MS, Miller CA, Trojanowski JQ, Kramer JH, Miller BL. Fronto-temporal dementia progresses to death faster than Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;65(5):719–725. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000173837.82820.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seripa D, Bizzarro A, Panza F, Acciarri A, Pellegrini F, Pilotto A, Masullo C. The APOE gene locus in frontotemporal dementia and primary progressive aphasia. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(5):622–628. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini MG, Murrell JR, Goedert M, Farlow MR, Klug A, Ghetti B. Mutation in the tau gene in familial multiple system tauopathy with presenile dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(13):7737–7741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumi SM, Bird TD, Nochlin D, Raskind MA. Familial presenile dementia with psychosis associated with cortical neurofibrillary tangles and degeneration of the amygdala. Neurology. 1992;42(1):120–127. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Blitterswijk M, Mullen B, Nicholson AM, Bieniek KF, Heckman MG, Baker MC, DeJesus-Hernandez M, Finch NA, Brown PH, Murray ME, Hsiung GY, Stewart H, Karydas AM, Finger E, Kertesz A, Bigio EH, Weintraub S, Mesulam M, Hatanpaa KJ, White CL, III, Strong MJ, Beach TG, Wszolek ZK, Lippa C, Caselli R, Petrucelli L, Josephs KA, Parisi JE, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Mackenzie IR, Seeley WW, Grinberg LT, Miller BL, Boylan KB, Graff-Radford NR, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, Rademakers R. TMEM106B protects C9ORF72 expansion carriers against frontotemporal dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127(3):397–406. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1240-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Shen Y, Chen W. Progress in frontotemporal dementia research. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013;28(1):15–23. doi: 10.1177/1533317512467681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]